Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

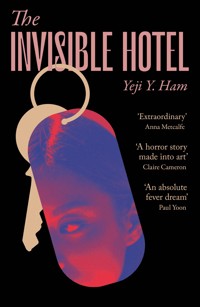

'Haunting, compulsive, stylish' ANNA METCALFE 'You won't be able to put this one down' PAUL YOON 'A horror story made into art' CLAIRE CAMERON ________________ Having grown up in the long shadow of the Korean War, Yewon is stuck in her small village. She dreams of a hotel, where there are infinite keys to infinite rooms - and a quiet terror she is desperate to escape. But when her little brother is conscripted into the South Korean army, Yewon's dreams start to seep into her reality, and she is forced to confront the unsettling truth about her country... Stylish, visceral and haunting, The Invisible Hotel is an unforgettable literary horror about the human consequences of war, and the toll of being born into a conflict that shows no signs of stopping. ______________ READERS ARE LOVING THE INVISIBLE HOTEL 'A really good book' 'Written with such maturity and sensitivity' 'I can't stop thinking about this book' 'Incredible' 'By turns horrific, surreal, sad, but not without humour and romance'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 369

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in the United States of America in 2024 by Zando Projects.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2024 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in 2025 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Yeji Y. Ham, 2024

The moral right of Yeji Y. Ham to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

EBook ISBN: 9781805460343

Atlantic BooksAn Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To my family

In the bathtub

I was born,

the bones were quiet.

1

It was my last day. My last paycheck. On the window, the manager was taping up a large sign: Permanently Closed. Another sign beside it: For Lease. Most of the store’s shelves had already been emptied and stuffed into a box. The manager glanced at the television mounted on the wall, then out the window, at a group of military men, smoking on the sidewalk. Their cigarettes flickered.

“I’m sorry.”

A dialect.

“I just couldn’t wait until Saturday.”

I pulled out a chair and took off my uniform vest. There were fewer people at the convenience store today. Three high school girls slurped instant noodles in the back. In the corner, a young man played a game on his cell phone, tapping hard at the screen with his fingers. I sat facing a clock—Ms. Han sat facing me, blocking my view of the clock a little. She put her bag on her lap. Her eyes, searching left and right. She smoothed her crinkled sleeves, her fingers bandaged. Maybe she was Korean Chinese? I wasn’t sure. She spoke in a dialect, but I couldn’t tell which province she was from. The manager walked by, glancing at Ms. Han.

“I’m Han Myung-ja.”

A few hours ago, she had texted me. She wanted to see me before this Saturday. I told her I had a shift today, but if she really wanted, she could come visit during my break. My break was only thirty minutes. I thought she wouldn’t come. My shift was late at night, and it was my last day at work. If there was anything to explain, she could just tell me on the phone.

“How do you know Mr. Kim?”

“His work,” she said. “The nursing home—I cook there.”

Again, a dialect. She paused with each word, as if she was thinking about how her mouth should work. Her tongue too. She was struggling.

“Last week, I asked Mr. Kim if he knew anyone who could help. He told me about you. I was wondering if you could drive me, if you were okay with the payment.”

“Just one trip?”

She said, “Yes.”

“Do you have the address with you?”

She nodded.

“I want to check the routes before we go.”

Carefully, Ms. Han picked a yellow note from her bag. Folded into a neat little square, worn out around its edges. She handed it to me.

“Yeoju.”

I stared at the note.

“My brother’s in Yeoju.”

“Oh.”

“They only give ten minutes for visitors, so.” Ms. Han’s voice suddenly picked up speed. “We’d have to leave here at ten o’clock, and I also work on Saturdays, so I need to be back in town by three. Before my shift starts.”

Words tumbled carelessly, twisting and rolling in her mouth. Ms. Han sounded so foreign. She was not from Seoul, but she tried to speak as though she was. Her tongue seemed unable to control the words in her mouth.

“He said you can’t drive?” I asked.

“I don’t have a car,” she said. “Or a license.”

The word car took a few seconds to speak and license several more. Ms. Han’s eyes looked heavy, like large accessories tugging down her flesh. Or like bowls, holding an overflow of emotions. She looked anxious. Ms. Han tugged her scarf. Everything on her looked big. Her scarf, her shirt. Even her puffed-up hair.

“I think I should let you know, though,” I said. “I don’t have a car. So, I’ll have to take my sister’s car. Her car is in Wontong. I’ll have to ask her first.”

“Oh, okay.” She patted her chest. “Please let me know.”

“You want me to drive you this Saturday?”

“Yes.”

Two days from now.

“Yeoju,” I said. “And we leave at ten.”

She gave a quick nod. “I work two jobs on the weekdays, from seven to nine. Saturday is the only day I can go and see him.”

Ms. Han lifted her chin. Her eyes trembling with worry. She stared at my hands, at the note I held. In her eyes, my fingers held a decision. I slipped the note into my pocket. I’d have to read it later. I could tell she didn’t want any questions.

“It’s already been so many years.”

A circle of duct tape rolled onto the floor. It had slipped from the manager’s hand. The manager was staring into the darkness outside the window. All the military men were gone now. Their cigarettes put out, the embers extinguished. Without them, the darkness looked so much deeper. Emptier too.

“I can’t take the bus, the train.”

Ms. Han’s voice, almost a whisper.

“But I need to see him. I need to.”

Ms. Han didn’t look any more relaxed than when she had first walked in. If anything, she looked more tense, her face paler. The door swung closed. The chime rang, clanking after the high school girls, gone now. Their noodle cups and bags of chips remained on the table. I sighed. I’d have to clean them up. I turned my face back to Ms. Han, who was still staring at the door. I glanced up at the clock. Less than two minutes, and my break would be over. The clock’s hands continued to run in circles.

“Your break.” She lowered her head. “You should go back now.”

Ms. Han got up, stumbling a little. She looked confused, as if she had just woken from sleep, as if she was trying to understand why she was here. Ms. Han was short, standing at the height of my chest. Maybe even as short as Mr. Kim’s mother, who was well over eighty years old. Blotches and spots on her face and hands. Her skin so tanned.

“Thank you. I will see you this Saturday, then.”

Ms. Han bowed. I returned the bow, and she walked toward the door, slightly bowing to the manager as she passed. As Ms. Han was about to push open the door, I saw her hesitate.

I walked to the tables in the back, clearing bags of chips and unfinished noodle cups. All to be thrown out. There was always too much wasted food. Even the food that didn’t get sold, that reached its expiration date: cartons of chocolate, coffee, or banana-flavored milk. Lunch boxes with barbecued pork, sweet marinated beef, and steak. Rice balls stuffed with tuna mayo or spicy stir-fried chicken, wrapped in crispy roasted seaweed. The manager told me I could take some of it home. Better that I eat it. I would take a few today, all expired and heavy inside my bag.

The young man in the corner was still playing the video game. His face, so close to his cell phone. A neon battlefield reflected off the window. Explosions, firing. His fingers tapped, tapped, desperately. I threw out the noodles in the food waste bin—it was overflowing. I needed to empty it. I grabbed the countertop cleaner and sprayed it on the table, waving away the whiff of spicy ramen sauce still lingering in the air. I rubbed my tickling nose and took out my vibrating cell phone. A text from Mother: Did you eat? I sneezed and shoved my cell phone back into my pocket.

“You dropped something.”

The manager pointed at the floor. The note. It was on the floor. It must have slipped out of my pocket.

“Is she a North Korean?”

He scratched the stubble on his chin.

“The woman you were meeting with. I’ve heard it before. That’s a North Korean accent.”

Carefully, I unfolded the note. Ms. Han’s handwriting was small and neat, the letters shaped in careful black ink. Written firmly onto the paper, like they were meant to be carved.

Yeoju Prison,107, Yanghwa-ro, Ganam-eup,Yeoju City, Gyeonggi Province.

A prison in Yeoju. Ms. Han’s brother. She wanted me to drive her to a prison. I turned over the note, hoping to find a different address, but nothing.

“She looks like a North Korean.”

The manager walked away. I studied the note more closely. Ms. Han had said, Visitors. Visitors were only allowed ten minutes. She had meant the prison’s visitation hours.

“Customers.”

I looked up. The manager grabbed the food waste bin and eyed the girls walking down the aisle. When had they come in? I hurried over to the counter, putting back on my uniform vest and tying up my hair. I shoved the note into my pocket and smiled.

“Welcome to Quick Four.”

Did Mr. Kim know about this—that Ms. Han wanted me to drive her to a prison? The girls put their baskets down on the counter. I scanned a pack of castella roll cake, two cartons of chocolate milk, and a stick of gum. If Mr. Kim had known, he wouldn’t have asked me. He knew that Mother would never allow it.

The two girls laughed. Whirling portable fans blowing their hair.

“It’s four thousand five hundred won.”

One of the girls glanced at the price.

“Would you like a bag?” I asked.

“No, we don’t need a bag.”

“Do you have a points card?”

One girl opened an app on her cell phone. The other handed me coins and bills. I counted and put them into the register. They grinned, tugging at each other’s sleeves. Whispering something about a guy in their class, about some teenage influencer, about how their school might really change their uniforms this time. They walked away, hugging their food, long ponytails swishing as they took a table in the back. Their charcoal blazers and green skirts were still the same gloomy colors as they had been three years ago, the talk of reform still empty. Min and I had hated wearing those uniforms.

I leaned over the counter, taking the note from my pocket, holding it up. I should have asked Ms. Han more questions. The stroke of her handwriting, slightly shaky. Maybe I should have left with Min. I should have gone somewhere far from here, like Seoul, to live in those tall apartment complexes, renovated and new. Crisp wallpaper, just pasted. Each room smelling of new paint. There was nothing for me here.

Yeoju, I murmured. Yeoju. I could do this as long as Mother didn’t know. It would just be one drive, and as of today, I needed another job. I straightened up, took my vibrating cell phone from my pocket. Mother. I shoved the note into my apron and answered.

“Watching the news?”

“What?” I asked.

“I sent you a link. You didn’t see it?”

“Mom, I’m still on my shift. I’ll call you back.”

“The news, it’s playing right now.”

I frowned, moving slightly to see the television, which always played the news. The passing subtitle on the screen was too small. Too far. The volume almost on mute.

South Korean Defense Minister promises to

“They’re talking about denuclearization. A peace summit.”

denuclearization and economic sanctions will be

“They are even talking about making the military voluntary.”

this summit will be an important step toward

“Then maybe your brother could get out early.”

President Oh—

“But North Korea launched two missiles last week. Why would they launch a missile if they want to talk about peace? It doesn’t make any sense and it’s not just nuclear weapons. How can we believe them?” Mother asked.

The rice cooker hissed in the background. Its vent caps rattled, letting out a long, agitated whistle. Mother wasn’t paying attention, ignoring everything but the television. Her hands, gripping her apron. Her back turned against the kitchen counter. The hissing continued. Mother had put in too much water again.

“I mean—” I sighed. “It’s at least a step.”

“A step?”

Water. I heard the sound of rushing water. Could she be? I checked the time. Was she filling up the kettle? Had she not washed them in the morning today?

“Your brother, did you—”

I sighed again.

“Mom, stop watching the news. Nothing’s going to happen. It’s a peace summit. It’s a good thing.”

Was she listening? She must have finally turned to the rice cooker, or the kettle. Everything was quiet now. Just some muted sounds from the television.

“You forgot to take your scarf this morning.”

“It’s not cold,” I said.

“It might get cold at night.”

I lowered my voice.

“I have to go now. My manager is staring at me.”

I hung up, about to move from behind the counter, when I saw it. The reddish rust stains spread on its metal body like some sickly skin disease. A small hole drilled into its head. A musty smell. The key. On the green countertop, there was the key. I picked it up, examined it.

I had never taken this key out of my room before. I would never.

Startled, I closed my hand as the girls burst into a shrill of giggles. Shaking their heads, slapping each other. What were they laughing about? On the television screen above them, I could see a dense smoke. Swirling colors of gray and black were spreading across the sky, swallowing up the entire expanse of calm blue. The growing flame pulled the smoke into its arms and pushed it out from its embrace. The motion, wide-reaching. Even the slightest movement, violent. The camera suddenly moved upward, and time began to push forward. Lapsing at a high speed. The sky cleared. Too quickly, the color became serene. As if nothing had happened, as if the gray and black of catastrophe had never taken place. The sky was blue again. Peaceful. Over the girls’ voices, I could hear a quiet ticking. The clock’s hands pushing toward the end of my last shift. Eight months. All the seconds, minutes, and hours I had spent here. Time was running forward, but here I was. Still at home.

I put the key in my pocket.

2

A scream. The words as empty as the voice. Weightless, neither masculine nor feminine, wrung out. Scatters of dust, rising from the carpeted floor. Wandering feet stumbling. A single light flickers. A dying bulb encased in a glass dome. Casting its rapid net of light, then yanking it back. Revealing for only a short moment a spread of greenish mold on the ceiling. The voice echoes. Clearer and louder. Some desperate words that tumble from a closing throat. Impossible to tell who, or what. I stare down at my hands. My fingers are clutching a doorknob. Crumbs of rust stuck on my sweaty palms. Nausea clogging my throat. A foul stink. Its sticky fingers wrap around my neck and tighten their grip. Putrid as sewage water, reeking of decomposition. I try to pull my hand back when I see him. His eyes buried deep in bruises. His sunken cheeks, grim purple. Standing behind me, the old man mutters, You.

——

“You there?”

I blinked.

“Hello?”

My fingers felt numb and painful. Blood, rushing back. The grab handles were swinging. The announcement display at the front was blank. The window. There was a window. And behind the window, outside. Outside, trees, trees, and trees were passing. A lamppost after another lamppost.

The bus rattled.

“Yewon?”

I looked down at my tingling hand. Eleven seconds. The time ticked. Twelve seconds. I was on a call. I didn’t remember answering it or even hearing it ring, but I must have.

“Yewon, are you there? Hello?”

It was Sister’s voice.

“I,” I mumbled. “Here, I’m here.”

I pressed my ear to the phone.

“You home?”

I rubbed my eyes.

“No, not yet. I’m on the bus.”

“Wasn’t your last shift today?”

I sat up.

“I thought you might be able to get off early.”

A dream, it was only a bad dream. A nightmare.

“How are you?” Sister asked.

I grabbed my bag from the floor of the bus and put it on my lap, glimpsing at the narrow aisle that stretched before me. Every seat was empty. I was the only passenger. I clutched my bag, gripping it tightly and wiping off my sweaty hands. Still shaking. I leaned back into the seat, trying to rest in the tumbling motion of the bus and feeling relieved. The cool temperature. The sight of the outside world. I was awake.

“I’m good. I’m almost home now.”

I glanced out the window, hoping to see where I was, but there was only darkness. The same darkness that I had seen on my way home for the last few months, stretching from when I got on the bus until I arrived home. The passing lampposts created a thin wave of light beside the bus, but it quickly dissipated into the night. Soon, the bus would carry the only light on the road. Closer to Dalbit village and deeper into the mountains, there were fewer lampposts. In the sky, I saw a crescent moon.

The train is now arriving.

I could hear the train platform on the other end of the line, the sounds of her commute.

“I read your text,” Sister said. “You were asking about the car?”

Please wait behind the yellow line.

I hugged the bag.

“I was just wondering if you took the car back.”

The train bound for Cheongnyangni is now approaching.

“What?” she asked.

“I wanted to ask if your car is still here,” I said.

“I can’t hear you. Wh—”

The train was arriving, carrying a deafening shrill. Like that scream.

“What did you say?”

“A ride,” I said.

“A ride? What ride?”

“Mr. Kim told me about this woman who needs a ride. I was wondering if I could maybe take your car.”

I heard doors swish open.

“Where are you going?” she asked.

“Yeoju.”

“That’s far.”

It was. Yeoju was about one hundred and seventy kilo-meters away from Dalbit. When Mr. Kim told me that it would be a four-hour round trip, I thought it might be Seoul. Seoul was two hours from Dalbit. But then, I shouldn’t have assumed. Two hours from here could be anywhere, depending on which direction I drove. Driving east or west. South or north. It could even be the ocean.

“What’s her name?” she asked. “The woman you’re driving.”

“Ms. Han. I think her name is Han Myung-ja.”

“She’s a friend of Mr. Kim?”

“They work at the same nursing home.”

“Okay, sure, that’s fine with me. You still have my spare car key?”

Mother hadn’t taken it from me.

“I have it,” I said. “But your car, where is it?”

“It’s in Wontong, at my friend’s house. I’ll send you her address. When are you going?”

“This Saturday, but I’m still thinking about it.”

“All right, just let me know when you decide,” she said.

“Okay.”

I tugged my backpack strap, thinking. Sister still hadn’t taken back her car. She’d left it in Wontong that night, after that fight, a month ago. Determined to never come back. To never set foot in Dalbit again.

Sister cleared her throat. Her voice sounded hoarse. Worn out. It was past eleven. Sister had worked overtime again.

“I thought you were going to take some days off,” I said.

She sighed.

“The conference, it’s not finished?”

Sister let out another sigh, this time with a chuckle.

“No?” I asked.

“There’s another one. This time, it’s in Busan. Unbelievable, right?”

“Your checkup,” I remembered. “How did it go?”

“I didn’t go.”

“What? Why?”

“I couldn’t.”

“But the doctor said—”

“That’s what you get for being too good at a job,” she said. “You get more work.”

I swallowed.

“Honestly, if they don’t give me a raise this year, I’m going to quit.”

Sister would never. She was just stepping away. She always did this when she didn’t want to talk about something. She would give some light-hearted answer, or let out that sigh. That one long, deep breath to fill her silence. I picked at my lips. She didn’t want to talk about it, but shouldn’t I say something? Ask if everything was all right with her. With Eun-woo. With everything else.

“Hey, just to let you know, though, I’m going to sell the car. I’ve been looking for car dealers.”

“Why?”

“It’s becoming such a hassle to keep it. Next year, our apartment is going to charge the tenants for parking spaces. The gas, the insurance, and now, this. It’s unbelievable how much I have to spend on that car. It’s just not worth the money.”

I didn’t understand. Eun-woo’s work was far from where they lived. That was why they bought the car. They couldn’t move closer to his work, in central Seoul. They couldn’t afford to. Sister said it would also save time for her. Eun-woo could drop her off on his way to work. Sister would no longer need to walk, take a bus, walk again to take the train every morning. A car was a more affordable and reasonable option. That was what she’d told me.

“As soon as I can get a good price on the car, I’m going to sell it.”

“Eun-woo is okay with it?”

“You need the car just this once?”

“I think so,” I said. “Unless she asks me to drive her again.”

The train is now arriving.

“So, Mom knows?” she asked.

The bus swerved. Turning around a sharp corner. I grabbed the seat in front of me, trying to pull my body up from the window. I wanted to ask Sister the same question. Did Mother know about her selling the car? Or missing her check-up?

The train bound for Chuncheon is now approaching.

My cell phone vibrated.

“Mom’s fine with you driving?” she asked.

I took my cell phone from my ear and glanced at the notification. Two texts. One from Min: I’m coming to Dalbit tomorrow morning. Meet you at the hill? The other from Mother, asking if I was on my way home. If I had bought the sponges.

“Jae-hyun,” I said.

“What?” Sister asked.

“Have you talked to him recently?”

“I did,” she said. “Why?”

“How is he?”

“Trying too hard. You know what he’s like.”

No, I didn’t.

“He’s doing good,” she said.

The bus screeched to a sharp stop, lurching me forward. The door swished open, and I moved a little to watch it, picking myself up. Someone was coming on board. But it was so late at night and going where? The few remaining stops were remote villages. I turned my face to the window. Outside the bus was a red-brick shelter. Worn and crumbling, abandoned. A bus stop. Under its awning light, on the bench, there was no one.

“I have to hang up soon.”

Sister spoke closer to the phone.

“That’s my train.”

It was time for Sister to board.

“If Mom’s worried about him, you should just tell her to stop worrying,” Sister said. “Jae-hyun is getting along fine. Just remind her that he can use his phone only when they’re allowed. He’ll get back to her. She always worries too much for no reason.”

I moved closer to the window, pressed my face right up to the glass. There was someone on the road, either coming to the bus stop or walking away from it. I squinted, trying to see through the dark. A slip of a person. Thin, too thin. The bus headlight just missed them, straying off the road. I tried to see the bus driver, to figure out why the bus had stopped. If the driver was waiting. He, too, must have seen someone. Or maybe it was an animal. A water deer. The door swished closed. The bus started rolling again. I watched as we passed the bus stop, the lampposts, the trees, trees. And there. A bony figure. There was someone in the dark. Slumping away as he dragged a window. Its glass, glinting.

“I was actually planning to call Jae-hyun today. Ask him if he needed anything. If you want, I can ask him to call you guys.”

“Okay.”

“All right, I have to go now. I’ll talk to you later.”

Sister hung up. I turned off my cell phone.

In the dream, I was certain he was dead. But that silhouette outside. On the road carrying a window. It was him. Yet he had just been in my dream. A dead thing. It was how he moved, how he looked. His arm a stretched cover of skin over twig-like bones. Purple bruises where something heavy had pressed deep into his flesh. His footsteps, carrying no weight, drifting. In that dream, all I could do was watch. I was deep asleep in my own body, which had forgotten itself. Lost. I watched from an unknown distance.

The bus stopped, and I got off. The air had cooled. Soon, harvest. Soon, winter. I sniffled.

The bus rolled away, leaving me at the bus stop, disappearing. I headed up toward our house. There wasn’t much here. Lampposts stood where the road bent, peeling off only a very small portion of the dark. The paddy fields and the mountains all breathed quietly, tucked under the night. I turned right, tracing the path I had walked ever since I was born. This darkness, this quiet, so familiar. I took in a deep breath, the air fluctuating. It was no longer sticky and stifling, but summer heat still lingered. The days were caught in between, an echo of dying and decay already in the air. The days of rustling green leaves and the cicadas’ noisy songs, taken over by the sound of leaves falling. Cicadas’ dead bodies, falling. The sun, falling earlier. Soon, it would be cold.

I stopped before a bright circle of light cast on the road by a lamppost. My shoes just touched its rim. The next lamppost was some fifty meters away. I stepped in. Standing under the light, I could see the brick fence in the near distance that went around Mr. Kim’s house and toward ours. Bowed and bulging, almost bending over. I turned, stepping back into the darkness, back on the road. Toward home.

I pushed open the rusty gate. The dry ground cracking under my weight. I kicked the stones and dirt as I passed Mrs. Lim’s house, right across from ours. Forty steps or less, the distance no more than ten meters. Her house was half a house. Too big to be a shed, but too small for people to live in. Father had planned to rebuild it with her son, Mr. Kim. An expansion of the living space. A construction for the new bathroom. An order for a new customized bathtub. Everything was now on hold.

I flinched at the sight of a face. A head in Mrs. Lim’s window. But that wasn’t possible. The window was too high up for her to reach. Her body was too weak. But she would have heard me arrive, always listening. I hurried across the yard, slinging the bag around to the front. I stepped up to our door, waving my hand, waiting for the motion-sensor light on the ceiling to turn on. Nothing. It wasn’t working. Broken again. I unzipped the bag’s front pocket, shoving my hands in, searching for the house key.

The moon cast a pale light onto our yard. Around and behind the fence, wild trees stretched. They looked more horrifying as the coming autumn slowly began to pick at their leaves, and their scrawny branches began to show. They loomed, creating a shadow over the already dark ground, snatching away the sunlight, or any light, from the life Mother kept planting. Killing all the flowers and vegetables. Our yard, grassless and flowerless. The fence, soon to crumble.

I pushed the house key into the lock.

Across the dark hallway, there was a slant of light spilling out from the only open door. I took a step, testing the squeaky floorboards with my toes, fixing my eyes on my bedroom door at the end of the hallway. Ten, fifteen steps. Past the bathroom, and there, I’d reach my room. I felt for my earphones in my pocket. I thought of putting them in as I came near the photo, just three steps before the bathroom. The family portrait. Sister drawing a happy expression, curling her lips into a smile. Me with a startled face, my shoulders lifted up toward my ears, my eyes half-crinkled. Jae-hyun, a baby just out of the hospital, resting in Mother’s cradling arms. The light didn’t reach Mother and Father. Their smiles stayed tucked away in the dark. I stopped, putting my hand on the wall. It was the only formal family portrait we had before Jae-hyun jumped from Mother’s lap and saluted his goodbye. Before Sister walked out. Before Father’s face, body, and hands all went missing.

I could hear the squelching sponge, the screeching stool that scratched against the tiles, Mother’s loud heaving. I had to walk quietly in the hallway, without being heard, or she would stop me, make me stand by the bathroom.

My stomach began to thrash. I didn’t want to see it. I didn’t want to smell it. Heat, breath, sweat, the odor that rose into the air and found no escape. Trapped inside for too long. Rotting. Decayed. The nauseating stench that rose from the bathtub. The stench that had become the skin of our home. That wet, sticky smell, as though someone were screaming to me: this is how you’d smell if you died.

“You’re home?”

Half of my body caught in the bathroom light.

“I didn’t hear you come in,” Mother said. “You want to wash? I can wash them later.”

Three, four steps. Only a few more steps to my room.

“I’ll wash later,” I said.

Mother was watching me. Staring at me long and hard, as though she was waiting for me to tell her something. I clenched my fists, my back starting to sweat. What if Mr. Kim told her? What if Mother knew? If she knew that I was thinking of driving a stranger to prison and I hadn’t told her—

“Did you try calling Jae-hyun?” Mother asked.

“No.”

“He keeps saying everything’s good there.”

“I’m sure he’s fine then.”

Sister said she was going to talk to him. He would tell her if something was wrong. I rubbed my temple. The front line. That’s what Mother kept telling me. Your brother’s on the front line. Jae-hyun’s army base was less than an hour from the border to North Korea.

“I think he’s not telling us everyth—”

“Mom.”

“You know how he doesn’t want us to worry.”

“Mom.”

“He didn’t sound well. His voice.”

“Mom, you’re overreacting, I’m sure he’s fi—”

The basin clattered to the floor. I sighed, stepping into the full light. One of Mother’s eyes was swollen, her face dripping with sweat. Her neck, arms, feet were bloody red. Worryingly red, as if every vein in her body had burst. Mother picked up the basin and turned her wrist.

“I told you about the news.”

I tried hard not to frown.

“That poor boy shot himself. Your brother is so much closer to the border. I don’t know how we—”

“Mom, I’m tired.”

Mother shook her head. She knew I was not listening. I was, but not in the way she wanted. Not in the way I could ever figure out.

Mother winced as she grabbed the sponge. Both her hands were covered with small yellow shreds, pieces stuck in her hair and on her t-shirt. Mother squeezed and squeezed the torn sponge. I had forgotten. Three, she’d said. Can you buy me three? This week, she had asked me to buy sponges, and yesterday at the store, I had put them away, thoughtless. The manager had pointed at the boxes of supplies to pack away before the store closed. Tissues, toilet paper, and packs of sponges, but even as I held them in my hands, I’d forgotten.

“Again. You forgot again. How many times do I need to tell you?”

I used to help her. It was our family tradition. Early mornings, I stood here with the kettle. Slowly, she’d say. She would ask me to pour the water into the basin, and she would direct me. Slowly, very slowly. As I poured out the steaming water, I watched and listened as Mother taught me. The red basin was for washing, and the blue was for drying. The bigger basin was for bigger pieces, and the smaller basin was for smaller pieces. You have to be careful with them, she always told me. But her hands. Mother soaked the sponge. Wasn’t the water too hot? Mother dipped her hands into the steaming water. Didn’t her hands hurt? Yes, they hurt. Mother grabbed a blue towel from the blue basin and wiped her face. The blue towel for drying. I remembered. I glanced at the sink. A bath. The thought was coming again, aching. The thought of lying inside that bathtub. The warmth I would never feel.

“I’ll text him.”

Mother started to scrub.

“I’ll ask if he needs anything. If he’s well.”

The remaining sponge shredded.

“I’m sure he’s doing fine.”

Mother grabbed a collarbone from the bathtub. She turned it, looking for a spot she might have missed. She caressed it, carefully putting it into a small blue basin as if she were laying down a newborn. Pellets rolled, clattering and rattling. I stepped back into the dark. Some were tiny, as small as my pinkie. A phalanx. Maybe a toe. In the basin, what would have been a scapula. A shoulder blade. Or something of a spine, a sternum. Shattered pelvis, scarred ribs, and snapped femur. Too shattered, too burnt, destroyed. Not a single bone was whole. As many as a hundred lay inside the bathtub. Torn and shredded. Their born color, their born flesh, buried underneath. Hardened black powder coated each broken piece. They waited for Mother’s hands. Mother rocked as she started washing them again. She picked up the sponge, squeezing, finding a faster pace. Mother scrubbed the collarbone.

My back hit the wall, in the darkness of the hallway. I stared at Mother, but she did not see me. Her eyes were fixed on the collarbone. Her ears tuned to the quiet of the bones. She cupped the liquid, pouring the hot, soapy water onto the collarbone. I didn’t know what would stop her hands. These bones were never going to wash clean. They were and had always been the color of burnt crumbles. Painful black, Mother used to say. The bones are the color of painful black.

“I changed your blanket.”

Mother’s voice rang behind me.

“Night’s getting colder.”

3

Min stretched out her legs. She took two cans of beer from a plastic bag and handed me one. We sat, with the full view of Dalbit spread beneath us.

The hill overlooked the entire town. A stretch of paddy fields and a scatter of houses. I could even see the road up ahead. One single road, it entered from the highway, snaked its way around the houses and fields, then left again. One way in, one way out. I kicked away the empty soda cans. Plastic bags, soju bottles, and plastic wrap. Weeds shooting up from the scorched yellow grass. Behind me, a broken gravestone, long forgotten. The wind blew, tussling my hair. Min’s permed hair smelled sweet. Mine smelled dusty.

The passing of time couldn’t be more visible. Soon, the ginkgo trees on the side of the road would bloom yellow. The huge chestnut trees that stood beside the small village supermarket would pop up with a cluster of dark, spiny husks, and the persimmons would blossom with their sweet, juicy fruits. Then, all the grandmothers and grandfathers would come out to harvest. Not only their fields but also the ginkgo trees, the chestnut trees, and the persimmon trees. They’d find a long stick to whack, shaking off all the fruits and nuts to eat in the winter. They’d go to their fields and carry away the sheaves to ready for the next season. Everyone in Dalbit sat in the same place, like the grandmothers in front of the supermarket removing the heads and intestines of small dried anchovies, or chopping green onions. Like every grandmother and grandfather here, they worked their fields. Soon, they’d start planting ponytail radish and mustard greens to make kimchi in the winter. Their hands always stayed busy, working with whatever each season brought to them, preparing for what would come.

I tapped my shoes together. Min and I sat comfortable in the distance, hidden from everyone else. From the height of the hill, I could see him. The old man. He was on a side trail, walking the narrow dirt path that went between the paddy fields.

“You said she’s a North Korean? The woman you’re driving to Yeoju.”

“That’s what my manager said,” I said.

“Did you ask her?”

“No,” I said.

Min dusted off her shoes.

“I’ve never met a North Korean before.”

“Me neither,” I said.

“I heard they try to hide it.”

“Hide it?”

Min shrugged.

“Hide that they are from the North?” I asked. “Why?”

She shrugged again. I moved a little to the side, giving her some space.

“Don’t they live well now?” Min asked.

“Who?” I asked.

“The North Koreans, I heard they live well now.”

“Really?”

“Someone said it,” she said.

In the distance, the old man stopped. He set something down on the ground, then looked up at the cloudless sky. The sky, with nothing to block its view, seemed to be watching him. The old man and the sky, in conversation.

I pulled down my sleeves, uncomfortable. Whenever I saw him, I instinctively startled. I leaned forward, wondering if the old man had always wandered the streets like this.

Min popped open a bag of chips, throwing them into her mouth and chewing loudly. She didn’t seem to mind the old man. He was standing completely still now, shaking his head violently.

“Hey.” I nudged her. “You see him?”

Min opened the can.

“What is he doing?”

She wiped her mouth. “I should have bought the original flavor.”

I stared at the can. Yuja flavor.

“So?” Min asked. “You said you were going to tell her.”

I rolled the can in my hands. Her plan. Our plan. I was going to move out of Dalbit, and Min was going to move out of her grandmother’s house in Seoul. We’d get a small studio together. Share the space and split the rent. As soon as you move to Seoul, she’d said, I’m moving out. She couldn’t stand living with her grandmother anymore, but there was no way she could afford to live alone. Neither of us could. I’d asked her, Why don’t we share a place? We could be roommates. Min liked the idea.

“I saved some money, but that won’t be enough.”

“We could rent those cheap half-basement or rooftop apartments.” She drank. “Or we could find two more roommates and split four ways?”

Min paused and stared at her fingernails, wiping them on her pants. She grabbed the chips carefully, slowly, trying not to get her fingers greasy and sticky this time. She slipped them into her mouth.

“How’s the job?” I asked.

“Ugh.”

Min took a large sip of beer. She hated her job. The last few weeks, it had been so busy at the museum, full of parents dragging their kids along, teachers and their miserable students on a field trip.

“A complete pain,” she said. “My legs are always swollen from chasing after the kids.”

“I can’t believe it.” I nudged her. “You, working at a museum.”

Min pushed me back, “I wouldn’t have done it if that sunbae hadn’t asked me.”

“What sunbae?”

“A senior from my major. Very tall, very, very handsome. I heard he was scouted off the streets once.”

“He works at the museum?”

She nodded. “There’s a big event going on at the museum, and he was asking if anyone might be interested in helping out. Help curate the exhibits.”

“Sounds busy.”

“It’s fine. It’s only one shift per week.”

I tapped at the can, lukewarm.

“If you come up to Seoul, do you want to watch a movie?” Min asked.

“What movie?”

“There’s this new rom-com. The rating’s really good.”

“What’s the title?”

“I’ll send you the link. You know, they opened up a new movie theater in Gangnam with those big, comfy leather seats. Only sixteen seats in one auditorium. A premium theater. I got discount coupons. We should go.”

I nodded. Gangnam, Hongdae, and Itaewon. Min was always there, in those places—whenever I called her, I could never hear her; someone on the other end of the phone was always shouting louder. Ever since Min had moved to her grandmother’s in Seoul, she’d uploaded more and more photos. Hashtag, what to eat today. Hashtag, Hongdae fashion. Min said I must go visit. So much to do. So much to eat. A photo of her biting into a large rib-eye sandwich. Slurping a bowl of hot and sour red Thai soup with shrimp, lemongrass, and chilies. A live stream of Min posing in front of some gigantic screen boards flashing with the name of a luxury brand. A muted gold watch, ticking. Hashtag, daily in Seoul. Hashtag, night view in Seoul. I scrolled through her photos. The night and dawn as bright as the morning. Restless bodies keeping the city wide awake. Refusing sleep. There was not a single street that wasn’t crowded, pouring with people, the bright magenta and cyan lights coloring every frown, smile, tear, and grin into one single emotion. A burst of excitement. I felt the thrill, even through the screen. I looked at Min’s photos and imagined I was there, with her. That I was far from here. Anywhere but here.

The old man stepped into the main road. I squinted to see him. He was dragging something long and horizontal.

“Do you want to meet him?”

Min took out her cell phone and showed me a photo. A guy. She smiled.

“I’ll introduce you to him when you come to Seoul. How about a double date?”

“Me?” I asked.

“His name is Tae-kwun. He goes to my university,” she said.

I pulled the grass, nervous.

“I think you’ll like him. He’s one of those serious types. He’s quiet at first, but once you guys start talking, you’d like him.”

“I don’t know. I really can’t imagine myself dating.”

“You need to start seeing people. We’ll do a double date,” Min said. “Plus, he just got out of the military, so you won’t have to worry about waiting for him.”

“Ji-hoon can’t delay his enlistment?”

“Ugh, don’t ask.”