6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

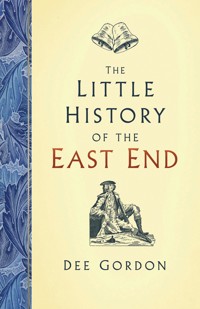

The Little Book of The East End is a funny, fast-paced, fact-packed compendium of the sort of frivolous, fantastic or simply strange information which no-one will want to be without. Here we find out about the most unusual crimes and punishments, eccentric inhabitants, famous sons and daughters and literally hundreds of wacky facts (plus some authentically bizarre bits of historic trivia). A reference book and a quirky guide, this can be dipped in to time and time again to reveal something new about the people, the heritage, the secrets and the enduring fascination of the original home of the Cockney which is now far more diverse. A wonderful package and essential reading for visitors and locals alike.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title Page

Introduction

1. Crime & Punishment

2. Romans, Royals & Some Rare Finds

3. Leisure Time

4. Earning Dosh

5. People

6. Places

7. Battles & Wars, Riots & Strikes

8. Death & Religion

9. Cockney Culture

10. Natural History

11. Waterways, Railways & Other Ways

12. On This Day

Acknowledgements

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

As an East Ender myself, I know that the description ‘East End’ means different things to different people. So, for the record, ‘my’ East End is bordered by Aldgate in the west, the River Lea in the east, the River Thames in the south, and Hackney Road in the north. So Spitalfields, Shoreditch, Poplar and East Smithfield, for example, are in the East End, but Hackney, Walthamstow, West Smithfield, Stratford and Dalston are not. There follows an amalgam of fascinating facts that will interest the trivia buff, the historian, East Enders (past and present), tourists and just the downright curious. Whether you want to learn, to smile, or to be amazed … then there’s something here for you. Here’s a small taster of what’s in store:

When Poplar became a parish in the early nineteenth century, they had to provide their own fire engines. By 1819, they had the ladder – but the fire engine didn’t arrive for another four years.The earliest person known to have lived in London was found in Blackwall, in the Yabsley Street area. The skeleton found here, in a crushed burial (indicating, by its foetal position, either a ritualistic return to Mother Earth, or, more practically, the need for a much smaller grave) was dated back to the Neolithic period, around 4,000 BCE.

When slavery was abolished in the nineteenth century, most of the 15,000 (circa) Londoners who were freed were living in the East End (London being the fourth largest slaving port in the world).

The first Peabody Buildings (housing for those on the lowest of low incomes) were built in Commercial Street, Spitalfields, in 1864. The tenants were provided with the luxury of nearby shops, baths and laundries, and the buildings remain, but as private housing.

The designer of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Melbourne was William Wardell from Cotton Street, Poplar, the son of a baker who was Master of the Poplar Union Workhouse. He emigrated to Australia in 1858, the year the work was commissioned.

There were more Irish in the East End than in Dublin following the Irish famine of the 1840s.

In February 1756, Mary Jenkins, who sold old clothes at the Rag Fair in Rosemary Lane, sold a pair of breeches for 7d and a pint of beer. The breeches turned out to be worth rather more, however, when the purchaser ripped open the waistband and discovered eleven gold Queen Anne guineas and a £30 banknote.

Officially, no Cockneys were born between 11 May 1941 and 21 December 1961 because Bow Bells (in the City of London) were destroyed in an air raid and not restored for twenty years.

In 1911, Thomas Cook featured an ‘Evening Drive in the East End’ for 5s, in their brochure How to See London. These ran every weekday from Ludgate Circus to Whitechapel, Bethnal Green, Limehouse and China Town. Their programme was particularly reassuring that this ‘unique evening drive incur no personal danger’ with only one stop – at the People’s Palace – where passengers would alight. They also stressed the area’s ‘good policing’ with the ‘sweeping away of many vile alleys’ in spite of the ‘almost entirely unrelieved sordidness’ – it must have been a charming way to spend an evening!

The Lansbury Estate in Poplar was built as part of the 1951 Festival of Britain to provide an example of futuristic housing in an exhibition of live architecture. The strap-line was ‘New Homes Rise from London’s Ruins’. However, the transport links between it and the Festival Hall on London’s South Bank had not been effectively planned, and far less people than anticipated made the trip to the East End to view the new estate.

The first beauty competition to be held in the East End was at the Cambridge Music Hall, Spitalfields, in 1904. Entrants were not allowed to wear make-up, and the competition was won by the natural beauty of Miss Rose Joseph.

1

CRIME & PUNISHMENT

PUNISHMENTS IN THE GOOD OLD DAYS

Gallows

Until the fifteenth century, pirates were often hanged on a gallows raised on a hill by East Smithfield, but the scaffold was then moved to Wapping where it became known as Execution Dock (on the site of what is now Wapping Underground). Famous executions that took place here included that of Captain William Kidd, hanged in 1701 (a pub named after him remains in Wapping High Street). The last men to be hanged for murder and mutiny on the High Seas were George Davis and William Watts, hanged here in December 1830. The gibbet was constructed low enough to the water so that the bodies could be left dangling until they had been submerged three times by the tide. On a 1746 map of the Isle of Dogs, other gibbets were indicated on the riverside.

Stocks

One (of many) remains in the vestibule of St Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch, along with the parish whipping post.

Pillories

Some locations (again of many) were at Red Lion Street in Whitechapel, Broad Bridge in Ratcliff, Broad Street in Wapping, the village green at Bromley-by-Bow and opposite Christ Church, Spitalfields.

Other Methods of Chastisement

A ducking pond stood on Whitechapel Green for ducking scolds, drunks, gossips and witches.

A prison and court house were established in Neptune Street (the South side of Wellclose Square) by the eighteenth century, originally for debtors but extending its brief later. One plea, dated 1758, reads ‘Please to remember the poor debtors’. Although there are stories of it being linked by tunnel to the Tower of London and the docks (from which the convict ship Success left), this seems unlikely. A part of a cell from this prison can be seen in the Museum of London, complete with graffiti of such images as a hangman, seemingly etched with a pine cone.

There are also records of an eighteenth-century prison specifically for debtors (known as Whitechapel Prison), alongside a ‘court of record’ for debts of under £5 ‘contracted in Stepney’, which was located in Whitechapel Road.

The guard house which remains on the Isle of Dogs had a twin, both next to a drawbridge over the moat around the dock walls (from 1803), which was used for holding prisoners in the short term (the other was an armoury but is now a newsagent!).

Poplar Gaol, incidentally, was not what it seems – it was the name given to Poplar Baths when they opened in 1934 in East India Dock Road, thanks to its grim exterior.

GRIM GANGLAND DAYS

Notorious gangs in the East End over the years include: Unemployed gangs of casual labourers who specialised in ambushing droves of cattle on their way to Spitalfields Market, covering the area between Stratford and Old Ford in the nineteenth century.

The Old Nichol Gang, who were responsible for terrorising local residents in Shoreditch in the nineteenth century.

The same period also boasted the Monkey Parade along Bow Road – gangs of teenage boys who molested passers-by, using lamp black to smear their faces, undeterred by fines of up to 10s.

A little later came the Bessarabian Tigers, mainly from the Bessarabia region of Romania, who specialised in blackmailing prospective brides with skeletons in their particular closet as well as running a pre-Krays protection racket. They were also known as the ‘Stop at Nothing Mob’ and wore distinctive oversized jackets and peacock feathers.

The Odessans from the Odessa café in Stepney, one that refused to pay protection, became a gang with a similarly violent reputation.

Bogard’s Coons supplied muscle for street traders, and were led by Ikey Bogard, a Jewish pimp who dressed as a cowboy.

The Watney Streeters, probably the largest gang, had one particular member – George Cornell – who was unlucky enough to clash with the Krays.

The Sabini Brothers – six of them – came from Hoxton. They were known as ‘The Italian Mob’ and were said to import ‘assistance’ in the form of extra gangsters from Sicily, and specialised in race course crime after the First World War.

The Vendetta Mob, run by Arthur Harding from the slums of ‘The Nichol’ in Bethnal Green, had a preference for holding up card games in the Jewish ‘spielers’ (gambling houses) and claiming the proceeds – often just a few pounds.

P.S. The 2002 video game The Getaway features the Bethnal Green Mob, an ‘old style’ family of Cockney criminals.

TWENTY JACK THE RIPPER SUSPECTS

Prince ‘Eddy’ Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence, said to have fathered an illegitimate child following his visits to brothels. His hunting experience would have provided knowledge regarding disembowelling, and his activity could have been prompted by a possible diagnosis of syphilis, adversely affecting his decisions and behaviour.

James Stephen, the Duke of Clarence’s tutor at Cambridge, who was gay and quite possibly jealous of the duke’s heterosexual relationships. This gives two potential reasons for murder: a cover up for the duke, or jealousy. He allegedly starved himself to death (sources vary) after the duke died.

Sir William Gull, Physician-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria and freemason, reported to have been seen in the area at the right time, also with a reason for covering up scandal.

John Maybrick, who was murdered by his wife in 1889. His diaries turned up in 1992 ‘revealing’ (contentiously) his identity as Jack the Ripper.

Irishman Dr Francis Tumblety who fled London at the right time (1888) while awaiting trial for indecent assault – he died in 1903 leaving a collection of preserved uteruses behind.

Dr Grant, or Michael Ostrogg, who may have been a ship’s surgeon but was certainly a confidence trickster. He spent several spells in asylums.

Frederick Deeming, who murdered his children and two wives, the second in Australia, for which he was hanged in 1892.

John or Jack Pizer, known as Leather Apron, a Jewish shoemaker with a collection of lethal blades. He had a conviction for stabbing and fitted the available description(s).

Aaron Kosminski was a Polish-Jewish hairdresser with mental health issues who lived with his two sisters in Sion Square, off Whitechapel Road. He was committed to an asylum in 1890, and said to ‘hate’ prostitutes. He survived another twenty-eight years.

Dr Thomas Cream, a specialist in carrying out abortions, who was subsequently hanged for poisoning some of his patients both in America and in South London. He is said to have confessed on the gallows.

Carl Feigenbaum, who faced the electric chair for murdering a woman in New York, was named by his lawyer (!) as Jack the Ripper after his client’s death.

William Bury who was hanged for the murder of his prostitute wife in April 1889, her body mutilated in similar fashion to the Ripper’s victims.

Walter Sickert, the artist, who may have been responsible for the anonymous confessional (?) letters sent to the police, and took a detailed interest in the murders.

Sir John Williams, royal obstetrician, said to have killed the prostitutes to research infertility.

Montague Druitt, whose father, uncle and cousin were all doctors. He was often in the area visiting his mother in a Whitechapel asylum, and he was found drowned in the Thames in December 1888, perhaps having committed suicide after the murders.

Joseph Barnett, the lover of the Ripper’s last victim, Mary Kelly. One theory is that he killed the first victims to persuade Mary to change her lifestyle, but she found out and they argued, resulting in her death.

Francis Thompson, who failed at medical school and turned to writing poetry after an unhappy love affair with a prostitute.

James Kelly, who escaped from Broadmoor early in 1888 (confined there for the murder of his wife). He also spent time in America at a time when similar murders occurred there.

Dr William Thomas, a Welsh GP, was living in Spitalfields when the murders took place – but returned to his village (coincidentally?) after each murder. His suicide followed the last of the Ripper murders.

Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland, who is said to have revealed his guilt by coded messages in his book!

… AND THE RIPPER OFF THE RECORD

Commissioner of Police during the Ripper investigations, Sir Charles Warren, could have done better, to put it mildly. One of his bright ideas was to spend an extravagant £100 on a pair of bloodhounds, Barnaby and Burgho, who promptly became lost dogs and needed the police to find them.

The Ripper’s crimes did not take place in dark, fog-filled alleys, but in the long clear nights of late summer and early autumn.

One victim (Catherine Eddowes) was killed on the same spot where a monk stabbed a woman praying at the altar of the Holy Trinity Monastery, before killing himself, in 1530.

It seems that one of the directors of the Bank of England dressed as a navvy during the night to scour the Whitechapel streets with a pickaxe, hoping to catch the killer.

Here’s a clue: Jack the Ripper was left-handed. So that narrows the field then.

SOME MORE LEGENDARY EAST END VILLAINS

Jack Sheppard, the highwayman, was born in White Row, Spitalfields, in March 1702, and baptised at St Dunstan’s. His short-lived career included an escape from St Giles Prison (through the wooden ceiling) and three escapes from Newgate, setting a record in escapology. He was finally executed at Tyburn in 1724, watched by 200,000 spectators.

George Smith, the ‘Brides-in-the-Bath’ murderer, was born in Roman Road, Bethnal Green, in January 1872. His three brides were all murdered the same way, all while on honeymoon, and all for insurance money, but George still had enough bravado to protest his innocence – before being hanged (in 1915).

The runner-up for the title of Prime Undiscovered East End Villain after the Ripper is probably Peter the Painter, the mysterious Russian anarchist who vanished from his Stepney address following the Battle of Stepney in January 1911. He and his Communist gang had been involved in the bungled jewellery burglary a month earlier (not their first crime), which resulted in the deaths of three policemen, leading to the ‘Battle’ (or ‘Siege’).

Jack ‘Spot’ (from the mole on his cheek) Comer, born in Myrdle Street, Whitechapel, in April 1912, made a fortune apparently from book-making, but in actuality from running a protection racket for East End Jews. He kept the Fascist blackshirts and others at bay under the façade of ‘The Market Traders Association’. After having his face slashed in 1955 and again in 1956, he called it quits and opened a furniture shop instead.

The evidence suggests that Sweeney Todd, the demon barber of Fleet Street, was born in Brick Lane, Spitalfields, in October 1756. He spent some of his childhood in prison before becoming a prolific serial killer. Although charged with just one murder (of Francis Thornhill), 160 sets of clothing were found at his shop, and he was hanged on the 25 January 1802 and sent, ironically, for dissection.

THOUGHT YOU KNEW EVERYTHING ABOUT THE KRAYS?

Ronnie Kray never had fewer than 50 shirts at one time, rarely wearing one more than twice – and his socks were always of black silk.

When Barbara Windsor and the cast of Sparrows Can’t Sing were filming around Cambridge Heath Road and other parts of the East End in the early 1960s, the Krays were hired to provide security on the set and can be seen – briefly – on screen.

The twins had a private masseuse and manicurist, and regularly visited a local gypsy to have their fortunes told.

When Reggie Kray married Frances Shea in April 1965 at St James the Great in Bethnal Green Road, the wedding photographer was Leytonstone-born David Bailey, who did the job ‘for free’.

When Ronnie Kray shot and killed George Cornell in The Blind Beggar, Whitechapel Road, in 1966, the record playing on the juke box was ‘The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore’ by the Walker Brothers.

The Kray twins’ trial at the Old Bailey in 1969 was the Old Bailey’s longest criminal trial, lasting no less than thirty-nine days.

When Ronnie Kray’s body was laid out at the funeral parlour in Bethnal Green Road in 1995, his dentures allegedly went missing. Well, he wasn’t going to need them.

The final piece of music played at Reggie Kray’s funeral at St Matthew’s Church in Bethnal Green in 2000 was ‘My Way’.

The Kray family burial plot is not in the East End, but is at Chingford Mount; and not only the Krays and their parents are interred but also Frances Kray, who – apparently – committed suicide in 1967.

Oldest brother Charles Kray died in prison in 2000 while serving time for masterminding a cocaine-smuggling operation.

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

Ratcliff Highway (now The Highway) was notorious as the site of four murders in December 1811, resulting in a reward of 500 guineas being offered. Three more murders took place half a mile away (in New Gravel Lane) just days later, acknowledged to be by the same perpetrator. While murder was not uncommon, especially in the area, these murders took place inside locked premises rather than on the public highway, and were regarded as a new threat to society. All in all, forty false arrests were made before John Williams (a lodger at the Pear Tree in Old Wapping) was placed in the frame, and his ‘guilt’ was accepted when he hanged himself in Coldbath Fields Prison, Clerkenwell. As a result of his suicide, his body was buried with a stake through the heart at the junction of Commercial Road and Cannon Street Road.

The Top O’ The Morning pub in Cadogan Terrace, Bow, is just yards from the railway track where the body of murdered Thomas Briggs was found in July 1864, the first person killed on a train. He was taken into the pub, still alive, but died of his wounds, and his murderer Franz Muller was tracked across the Atlantic and caught as he disembarked in New York.

3 Nova Scotia Gardens (Spitalfields) was the home of two of London’s body-snatchers in the nineteenth century, John Bishop and Thomas Williams. Their luck ran out when they took a suspiciously fresh, young corpse to the King’s College School of Anatomy, alerting the police who found so much clothing on their premises that it suggested that literally hundreds of people may have been involved.

It was outside the Repton Boxing Club in Cheshire Street, Bethnal Green, that Freddie ‘Brown Bread’ Foreman abducted Ginger Marks in January 1965, later admitting to his murder.

The shoe shop don, Raffaele Caldarelli, was finally arrested in September 2006 (after ten years on the run) outside one of the shoe shops he owned at 5 Hackney Road (now Amore Tony Shoes). He had been living nearby for three years but had evaded capture in both London and Naples for charges of trafficking in drugs and arms, extortion and other Mafioso associations.

VISITING VILLAINS

When Charles II fell from favour in 1688, Judge Jeffreys, the notorious Hanging Judge, attempted to follow him overseas but was captured, disguised as a sailor, in the Town of Ramsgate pub (then the Red Cow) at Wapping. He was as frightened of the mob at home as he was of William of Orange’s approaching army, and only the intervention of the militia saved him from much worse than being imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he died some months later, of kidney disease (April 1689).

In 1737, Dick Turpin stole a horse from Epping and hid him in the stables of the Red Lion at Whitechapel. When his partner-in-crime ‘Captain’ Tom King went to collect the horse, the law was waiting, and a gun battle followed in Goodman’s Fields. As a result King was (apparently accidentally) shot and killed by Turpin, who then escaped.

A MEDLEY OF CRIMES AND CRIMINALS

Cowboy builders are nothing new, it seems. Thomas Slaymaker from Mile End Town appeared in court three times in the seventeenth century – for making poor joints, for defective bricks and for defective tiles.

Two Thames mudlarks (who made their living selling anything they dredged from the mud) from Rosemary Lane found that demand for ‘antiquities’ was exceeding supply so decided to make their own! William Smith and Charles Eaton produced the Billy and Charley forgeries (also known as the Shadwell Forgeries because they were said to have been retrieved from the Shadwell mud) in their own workshop. The fakes were mainly of lead and brass, shaped in moulds of Plaster of Paris, and bathed in acid to age them appropriately.

Medallions were the most popular seller, and they produced thousands of these, even though they were illiterate and many of the ‘ancient’ inscriptions were pure gobbledegook – but this was between 1857 and 1880, in the early days of archaeological advances. Nevertheless, they were caught and exposed in the end, but the law had no redress for their crime then, and they got away with it.

Young Patrick McQuinn made a minimal living in 1867 by cleaning the shoes and boots of gentlemen passing by his Leman Street pitch. But when Mr Abraham Woolf consistently refused to give the boy his custom, Patrick and his shoe-blacking chums resorted to violence. Having been struck down and kicked, Mr Woolf dragged the principal offender to the police station where he was sentenced to one month’s imprisonment and hard labour.

Upon his return from Australia, Arthur Orton, the son of a Wapping butcher, tried unsuccessfully to convince the courts that he was the long-lost Baronet Sir Roger Tichborne (the longest trial, then, in British history: 260 days). This was in spite of Lady Tichborne’s rather desperate acceptance of his claim; she was even said to have ‘recognised’ her son, who had completely different colouring and build and did not speak a word of what should have been his native French. He served ten years in prison, until November 1884.

When Messrs Spillberg, Nabian and Aaroris (sic) attempted to smuggle saccharin into their premises in Nelson Street, Stepney, they were trying to avoid Customs duty of about £500. The 2 hundredweight store of sugar substitute was concealed in wooden discs disguised as table tops, but was regarded (in 1906) as a ‘drug’ and the men were caught and charged with drug smuggling and intent to defraud Customs.

FAILED VILLAINS

William Brown broke into the New Baptist Tabernacle in Stepney Green in December 1868 with intent to ‘commit a felony’ but, in the dark, fell into a large cistern below floor level which had been used the previous evening to baptise several adults and not subsequently covered. When he finally managed to extricate himself, he found a bottle of port in the vestry to ease his troubles, and was found next morning in a state of ‘complete intoxication’ – and still a trifle damp.

Joseph Herrmann, a ship’s cook, broke into 32 East India Dock Road while Edward Bartier and his daughter were sleeping. He helped himself to a number of dessert forks and spoons before finding a bottle of gin – and was found next morning, fast asleep on a couch, woken by the police constable who had been called out by the Bartiers. In his defence, he claimed the gin had been too strong.

HERE COME THE GIRLS

Joan Peterson of seventeenth-century Wapping started out by selling medication for headaches and curing sick cows (by counteracting malicious witchcraft). However, when one recipient didn’t pay up, she turned to threats, causing – apparently – fits and prolonged illness. She was also, sadly for her, the owner of a black cat, and was even said to possess a ‘familiar’ – a squirrel. That was all the evidence needed to result in her being condemned to be hanged at Tyburn in 1652. Numerous books – and a play – have since been written about ‘The Witch of Wapping’.

The seventeenth century being the century of witches, Anna Trapnel, daughter of a Poplar shipwright, was also accused of witchcraft – and madness. Her story was rather different, because she had had a spiritual revelation at the Church of John Simpson in Aldgate and became a fervent – and political – preacher. She must have made good use of her gift with words because she was released just four months after her imprisonment.

Damaris Page (c. 1610–69), described by Samuel Pepys as the ‘great bawd of the seamen’, moved from prostitution to running brothels. Apparently she had one brothel in The Highway for ‘ordinary seamen’ and one in Rosemary Lane for ‘naval officers and gentry’, although these were targeted in riots in the 1668 ‘bawdy house riots’. Her main centre of operations was the Three Tuns, and the Duke of York was said to be among her ‘customers’. Although illiterate, she built several houses on Ratcliff Highway providing her with a life-long income, and she died a wealthy woman.

Elizabeth Gaunt, who lived with her husband in Whitechapel in the seventeenth century, moving to Wapping by 1683, was less lucky. A charitable woman, she arranged passage overseas for rebels, and carried messages for them over to the Netherlands. As a result, she was tried for treason in October 1685 at the Old Bailey, with one of those she had sheltered giving evidence against her. ‘Mother Gaunt’ was burnt at the stake at Tyburn just days later – the last woman in England to die so for treason.

Not content with her lot was Lady Ivy, born Theodosia Stepkins, famous for her wit and beauty and described as ‘cunning in law’. After three husbands, she owned a vast acreage in and around Wapping and Shadwell, in addition to being settled with saddle horses and jewellery, but she wanted more, and took Thomas Neale (who leased the land from the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s in London) to court in 1684. The judge was the infamous Lord Chief Justice Sir George Jeffreys. The lengthy and complex trial showed that Lady Ivy had forged a mortgage and counterfeited several deeds to substantiate her claim, and knew how to put saffron in the ink to make the signatures look older than they really were. As a result, Lady Ivy was tried for forgery, but was acquitted through lack of evidence against her personally, even though Judge Jeffreys commented on the witnesses who spoke on her behalf as being ‘guilty of notorious perjury’. (The disputed land now makes up King Edward VII Memorial Park.)