8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

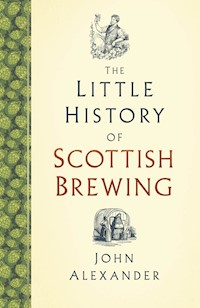

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

From the time of the Picts to the present day, Scotland has played an important role in the development of British brewing, providing a host of inventions and other contributions vital to its success. Covering such topics as Scotch Ale, Porter, Shilling Ales and the influential waters of Edinburgh and Alloa, The Little History of Scottish Brewing will intrigue both the aficionado and the interested enthusiast.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© John Alexander, 2022

The right of John Alexander to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781803992181

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey by Imak

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Historical Background

Hops and Herbs

Nineteenth-century Barley and Malting

The Victorian Brewery and Public House

Prohibition

Scottish Innovations and Technology

The Shilling Terminology

Military Associations

Commemoration Ales

Brewing Liquor

Yeast

Scotch Ale

India Pale Ale

Scottish Porter

Scottish Lager

Traditional Scottish Draught Beer

Bottled beer

Endnotes

Picture Credits

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Much of the following story has been collated over many years and the following people have all contributed in some way to the success of this book. Thanks to Innes Duffus, archivist of the Nine Incorporated Trades of Dundee. Iain McInally, Dr Les. Howarth, Kenny Mowbray and the late Bill Cooper of Scottish Craft Brewers. Keith Robson DA. The late Sandy Hunter, Monkscroft, Belhaven Brewery, Dunbar. Stuart Cail, Head Brewer, Harviestoun Brewery, Alloa. The late Gilbert Dallas, MBE, Dougall McCrorie, founder of the Craft Brewing Association. Paul Taylor, Laboratory Manager at Murphy’s, Nottingham. Duncan McAra, Scottish Tall Fount Supporters. Eric Dore of the Labologist’s Society. The late Dr David Johnston, ex-Head Brewer at Tennent’s, Glasgow. The late Harvey Milne, former brewer with Arrol’s Alloa Brewery. Simon MacMillan, BA Hons. CAMRA members Forbes Brown and Dr Stuart Rivers. Charles McMaster, BA, former archivist at the Scottish Brewing Archive, Edinburgh. Also, to Alma Topen, who became the archivist at the Scottish Brewing Archive, Glasgow University, at a very difficult time in 1992. To Sandra Gordon, researcher at the James Hutton Institute, Invergowrie and Howard Davis, ex-Director of the James Hutton Institute, Invergowrie, Perthshire.

INTRODUCTION

Brewing developed throughout the British Isles over a long period of time by practical and empirical processes, from simple cottage, farm and tavern brewing to eventual commercial brewing. Brewing was like baking, a local industry and commerce that was limited to how far a horse could travel in one day. In Scotland, the Browster-wives were the mainstay of domestic brewing scene and were numerous in every town and locality, and excess production was sold to the community. The Luckies brewed in the ale houses and were the forerunners of large-scale commercial brewing.

Most of the early beers, brewed with groot in Scotland, were sorry stuff, and it was only in the early 1700s that things started to change with the introduction of the hop, which had a huge impact on Scottish brewing, alongside improvements in agriculture that took place during the Industrial Revolution, plus the growth of the wage economy that saw a brewing industry develop in Scotland that was second to none.

There is nothing nationalistic about my history; it is just that I believe Scotland has a story to be told and no claim is made that we did it alone as, historically, brewers throughout Europe in some way exchanged information on their ingredients and methods. The creation of London Porter in the early 1700s also had a huge influence on fortunes of Scottish brewing, as did the introduction of India Pale Ale, which created a significant impetus for home and foreign markets.

Throughout the pages of this book the reader will come across many examples of the contributions made by Scottish inventors, brewers and people in agriculture, which influenced the brewing processes and technical innovations that had a positive impact on Scottish brewing, an industry that developed quite independently, and despite our diminutive population we punched well above our weight.

The process of brewing varied throughout Europe, with the Continentals adopting various methods of decoction mashing whilst the British stuck with infusion mashing. In the UK, brewing is the same south and north of the border but both countries developed the practice in separate ways. For example, the Scots tended to mash and sparge at a higher temperature and ferment at a much cooler temperature, which gave Scotch Ales their unique fullness of character. The English preferred to double mash and ferment at higher temperatures, with the consequence that both styles of beer had different characteristics.

As for hops, both countries used enormous amounts in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which was not so much for flavour but more as a preservative, and it was only during the latter half of the twentieth century that the Scots reduced the hopping rates to a level much lower than that used in English brewing. Also, it was during the late nineteenth century that Scottish mashing and sparging heats and fermentation temperatures, in general, came into line with English practice to increase output in order to compete with English exports to India, Australasia and the wider Empire.

Today, the modern approach to brewing in Scotland is little different from English brewing, and this has been brought about by the new generation of aromatic hoppy beers that are impregnated with floral hops late in the boiling. Consequently, traditional twentieth-century beer styles are a rarity.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

‘Beer is a very ancient drink – how ancient, nobody can tell, for the time of its origin was before the dawn of history.’

C.L. Duddington, Plains Man’s Guide to Beer, 1975

Just when and how the natives of the country we now call Scotland started to brew is lost in the mists of antiquity. However, one of the earliest references to brewing in Scotland is in the fourth century BC, when Pytheas of Massalia surveyed the Iberian Peninsula and eventually the coast of Britain as far north as the Orkney and Shetland Islands. He is also said to have visited Thule, which historians consider is either Shetland or Iceland, but the ancients considered Shetland to be the Ultima Thule, being the furthest northern part of the world. Pytheas noted that the inhabitants, the Picts, were accomplished in the art of brewing strong drink and he also gives us an early reference to oaten porridge and the use of oats, heather and honey in brewing.

The ‘Picts’ is a name given to indigenous Scottish tribes by the Romans and comes from the Latin ‘Picti’, meaning painted ones. The Picts were a thriving and energetic people who left their legacy on their exquisitely carved standing stones, which are scattered throughout the land, and their symbols are now thought to be connected to astronomy.

Much of the archaeological evidence is found in Skara Brae at Orkney, which is the best-preserved prehistoric village in northern Europe and is older than Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids. Other sites, such as Balfrag in Fife, The Howe on Orkney, at Kinloch Bay on the Isle of Rhum and on the Isle of Arran, tell us that brewing has been carried out in Scotland since Neolithic times. Much of the evidence comes from the residue of both barley and oats that have been detected in shards of broken pottery at The Howe, plus traces of meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria), heather (Ling, Calluna vulgaris), and black henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) that were used to flavour the brew. Smidgens of cereal pollen were also found, suggesting the making of mead or ale.29

Roasted barley was also found at The Howe and some historians suggest that it was used in brewing, but according to Edmund Burt,14 and probably prior to cooking, the Highlanders in the 1700s set their barley on fire to get rid of the awn and chaff and so some charring of the grains must have taken place. Presumably the Picts did likewise and so we cannot say for certain that the roasted grains found at The Howe were necessarily used for brewing.

Just how the Picts brewed is open to speculation, and their methods are, like their standing stones, a mystery. However, it was most likely that, like primitive peoples worldwide, they were simply trying to make grain more palatable and digestible and that alcohol was a happy consequence of their experiments. In its raw state grain is hard to chew and digest and so it was soaked in water to soften it, which would initiate germination and the enzymes necessary to convert the starch into sugars. Slow drying by the heat of the cooking fire in clay pots would create crude but palatable malt. To further increase the digestibility and tastiness of the grain, a simple method of mashing, by making gruel in an earthenware ‘mash tun’, would be essential, and if the pot was sat on the heat of the peat fire sufficient warmth would create a successful mashing and saccharification of the crushed oats or barley, producing sweet porridge. It is most likely that honey, fruits and berries were added to the porridge to add to the nutrient value and to enhance the taste.

However, a common theory is that if all this gruel was not consumed immediately and the remainder of the mash was left overnight by the warmth of the cooking fire, the malt sugars and honey would quickly be fermented by the yeast from the fruit and berries, which was the only source of yeast available to the early Picts, not that they would have a clue as to why this ferment occurred in the first place. Some authors suggest that the gruel was left outside the dwelling to become infected with wild yeast, but the question here is why? Why leave food outside the dwelling where it would be consumed by foraging nocturnal wildlife? Eventually they would separate the stimulating liquid by straining the mash through a perforated animal skin bag held over a shallow clay vessel, and possibly rinsing with hot water.

Some writers have suggested that the gruel left aside for a short period would turn rancid, and this is probably true. However, what might have tasted ghastly to modern man might not have tasted terribly foul to primitive people, and as noted by Dionysius of Halicarnassus in 25 BC, the Gauls used liquor made from barley rotted in water, which was disgusting both in smell and taste.29

A boiling vessel would not necessarily be required, as the strained wort would not require boiling prior to spontaneous fermentation by wild and fruit yeast. In this case, flavourings from plants, flowers and wild fruits could simply have been included in the mashing pot, where their flavour and aroma would be diffused into the mash. The use of meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) not only flavoured the brew but provided antiseptics to keep it palatable in the short term. Other plants such as belladonna (Atropa belladonna), henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) and hemlock (Conium maculatum) were also used and induced hallucinations, and their use is thought to be connected with religious practices such as shamanism in placating the spirits.

Should boiling have taken place, it would most likely have been by the ancient method of adding red-hot stones (pot boilers) from the cooking fires, a practice that is still used in Bavaria to produce Steinbier (Stone beer), and this practice would create caramelisation that would contribute to the flavour. A peat fire smoulders and whilst they were fine for cooking, they would not give off sufficient heat to bring a pot to boiling, although it is unlikely that boiling was conducted indoors due to the uncomfortable heat and choking smoke that would fill the low-ceilinged, windowless underground dwellings.

There is also evidence that the Picts waterproofed their vessels internally with bee’s wax, and this has been claimed to prevent the seepage of alcohol by evaporation. This is possible but is open to doubt, as it is unlikely that the brew would be stored for long periods as it would quickly go sour. Also, if we take the practice of peoples living in hot countries, they did not glaze their water storage pots so that the slow seepage through the clay evaporated and caused cooling and so the water remained fresh. Skara Brae exempted, the early Picts lived in hill forts, and although there is evidence that they dug shallow wells to collect rainfall, domestic water would have been stored in earthenware pots. Therefore, in the cold northern climate they would be unlikely to require vessels that sweated, causing the loss of such a valuable supply of water, and the waterproofing was necessary to conserve supplies. During times of drought, water would be acquired from the lower slopes and stored in pots.

The Picts eventually became an organised race indulging in pasturage, and so the art of brewing would have also been well developed. It is claimed that primitive sites of Pictish breweries have survived in Galloway. They are pear-shaped, about 5 metres by 2.5 metres with a side wall of about 1 metre in height, and were built on southern slopes close to running water.43 Sunken stone troughs were also discovered close to running water and are thought to be cooking (or brewing?) places for game and fish by adding pot boilers. Interestingly, it has also been suggested that the troughs might have been used to steam up primitive saunas.

Knowledge of Pictish brewing can be found on a tenth-century standing stone found at Bullion at Invergowrie in Perth and Kinross, and is now in the safekeeping of Historic Scotland. The stone depicts a warrior drinking from a horn that is adorned with an eagle’s head. The eagle’s head symbolises power and so the fighter depicted would have been a chief or noble warrior. One wonders, was the warrior drinking an oaten brew flavoured with the corn weed, darnel, or perhaps the fabled Heather Ale?

There are many myths about Heather Ale that have been passed on by oral tradition. One of the most enduring tales is that about AD 375, Niall of the Nine Hostages, the 126th High King of Ireland (died AD 403), crossed the Irish Sea from Antrim to Galloway with a view of exterminating the native Picts and acquire the secret of brewing Heather Ale.

And the fable continues: after a bloody campaign, the only survivors were Trost of the Long Knife, plus his father, brother and the Archdruid Sionach, who had betrayed Trost and threw his lot in with Niall. The victorious Niall had a parley with Trost and offered to spare the lives of his father and brother for the secret of Heather Ale. Fearing that his father and brother might give out the secret under torture, Trost assured Niall that if his father and brother were put to death first, he would reveal the secret recipe. Having sacrificed his father and brother, Trost told the king that he could only reveal the secret recipe to a member of his own race and that he would pass it on the traitor Sionach, out of earshot of the Irish. The king agreed, and Trost led Sionach away along the cliffside. When they were at the steepest part, Trost quickly turned round and grabbed the startled Sionach, shouting, ‘The secret dies,’ and both men fell over the cliff to their deaths.62

It is a marvellous tale, and one wonders what was so important about Heather Ale? The Scots with their Celtic culture, who later inhabited Scotland after ousting the Picts in the ninth century, considered many plants to have magical powers and wore them in their bonnets as talismans to ward off evil spirits and protect them from harm. So, was Heather Ale considered to have magical protective powers and drunk as a libation before battle?

There are many references to brewing Heather Ale in Scotland, principally in the Highlands and Islands, well into the twentieth century. In 1826, James Logan travelled throughout Scotland collecting information of antiquarian interest, which he published in The Scottish Gael, 1831. He, too, mentions the brewing of Heather Ale but, interestingly, he also mentions the use of heather roots to flavour the brew, which he claims imparted a liquorice-like taste. It might be that the roots were actually used as a crude strainer in the bottom of the mash tub to filter the wort as it drained from the vessel. Also, Bickerdyke, writing in Curiosities of Ale and Beer, 1886, states that heather was used primarily as flavouring and suggests that the taste of the brew was akin to heather honey. Yet, Heather Ale is not exclusive to Scotland – the Irish also brewed Heather Ale, and in Plot’s Natural History, 1677, we are told that in the district around Shenton, Leicestershire, brewers frequently used Erica vulgaris (heather, heath or Ling), to preserve their brews.44

Today it is appreciated that heather does not contain any fermentable matter and all references to brewing with it without some form of additional fermentable extract are simply a myth. This fact was evidenced around the turn of the twentieth century, when Dr Maclagan enlisted the help of Andrew Melvin, the son of Alexander Melvin who acquired the Boroughloch Brewery, Buccleugh Street, Edinburgh, in 1850, to carry out a series of brewing trials using heather. Their conclusions were that a brew could not be made with heather alone, but that heather could be used to season a brew just like hops.29

The Vikings, too, were also great lovers of ale and controlled Orkney and Shetland, the Western Isles and the north of Scotland from 794 until the twelfth century, and whatever brewing methods they might have had must have survived for some time. They most likely brewed with wild oats or bear/big and flavoured the beer with heather, honey, juniper and rowanberries.

In the early eleventh century, the oldest home brewery in the UK was built at Traquair House, Innerleithen, by Peebles, which was originally a hunting lodge built to provide accommodation for Scottish monarchs and nobility. The beer, which would have been brewed with groot, would have been brewed by the ancient ‘cottage system’ whereby the cleansing of beer was achieved by simply allowing the casks to fob and overflow and the slops were collected in a vessel below.

It was during the twelfth century that Scotland is reputed to have adopted the German method of brewing, brought here by religious orders, but there is no evidence to tell us just what such methods might have been. It might be, of course, that they introduced the Bavarian practice of long cold storage, or lagering, that became a regular practice in the evolution of Scotch Ale. In 1231, the Blackfriars Monastery was established at Perth and later the site became the Perth Brewery in 1786.

Brewing was largely in the hands of the monks, who had brought the craft to a highly skilled art, and in the thirteenth century the monks of Arbroath Abbey are said to have used more chalders (8 quarters) of malt than all other cereals put together.43 Such practice would be quite common, as ale formed part of the daily diet and monks consumed up to a gallon of ale a day. Monasteries were also hospices and weary travellers and pilgrims were refreshed with food and ale. It is recorded in the Rental Book of Cupar Abbey, for example, that the monks brewed several ales such as ‘Convent Ale’, which tells us that the nuns also had their daily tipple! They also produced ‘drink of the masses’, which would have been their weakest small beer handed out to pilgrims and travellers. ‘Household Ale’ was brewed for their own use and ‘Ostler Ale’ for sale to local alehouses and taverns. The strong ‘Better Ale’ was drunk on special religious days and holidays and was important to sustain the monks during Lent.

The Banff Brewery is said to be the oldest public brewery in Scotland, and production started about 1450–52. During this time the Lowlands was Scotland’s main trading partner and much interchange of peoples and goods took place, including beer. Scottish mercenaries also fought for the Dutch, and traders and soldiers would have been well accustomed to hopped beer. It is also claimed that hopped beer was first introduced into Scotland in 1482 and originally brewed by the monks of Banff, followed by the Blackford Brewery in 1488.8

The name Blackford comes from the twelfth-century legend when the Norwegian King Magnus lost his wife, Helen, who drowned whilst attempting to cross the ford of the River Allan close by. She was buried at Deaf Knowe near the ford and hence the village became known as Blackford. The Tullibardine Distillery is built on the site of the ancient brewery.

In 1488, when James IV was returning from his coronation at Scone, he refreshed his entourage with the ale of Blackford at 12s a barrel, and there is a reference in the Treasurer’s Accounts that states, ‘quhen the King cam forth of Sanct Johnston for a barrel of ayll at the Blackford’.8

In 1493, Bartholomew Bell of Edinburgh was awarded a silver medal by the city’s fathers for the quality of his beer.

During the sixteenth century, maltsters and brewers established Maltman Fraternities or Guilds to look after their interests and to control the selling of all goods brought into towns and burghs, and would issue temporary licenses for an individual to sell one specified lot of goods. The coopers of Glasgow, a most important body of artisans, formed The Incorporation of Coopers in 1551, to regulate their trade and look after their interests.

After the decline of monastic brewing, ale and beer was largely brewed for domestic consumption as it was considered safer than well water, which carried a risk of cholera and other water-borne diseases. Surplus ale was sold locally, and in the 1550s the average price of the ale in Dundee was 3/- a gallon (Scots) and lesser quality ale was available as cheap as 1/9d a gallon.

The Burgh Magistrates were responsible for the quality, strength and price of the ale and they regularly visited the taverns in their Ward to check that it be ‘guid an’ sufficient’! The overpricing of ale was frowned upon and carried severe penalties. In Dundee, during July 1562, David Ramsay was caught selling his ale at too high a price, and the Baillies confiscated his mash tun and other brewing utensils and burnt them. He was also forbidden from brewing for one year and a day.

In 1566, Mary Queen of Scots (1525–87) visited Traquair House with her son the future James VI (I) and she no doubt imbibed on Traquair Ale. Queen Mary’s reign was an unhappy one, and despite several attempts to reconcile the Catholic–Protestant divide she was captured by the Protestant lords and imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle. Thereafter she was held in Loch Leven Castle, Fife, and forced to abdicate in favour of her son, James VI. Within a year, Mary made good her escape over the border and threw herself at the mercy of her cousin Queen Elizabeth I, who was well aware of Mary’s designs on the English throne and imprisoned her in Tutbury Castle. Whilst imprisoned at Tutbury Castle, Mary acquired a taste for the ale from Burton Abbey, a habit that was to lead to her demise! As she was planning her escape, correspondence was passed out of the castle in the empty casks, which were intercepted by Queen Elizabeth’s chief of the secret service, Sir Francis Walsingham, and that signed her death warrant. She was taken to Fotheringhay Castle just outside Peterborough and put to the block in 1587.

In 1573, a new brewery was built at Traquair House that survived until the 1700s. In 1578, John Leslie, the Bishop of Ross, wrote in his History of Scotland that English beer brewed with hops was superior to Scots ale brewed with groot, but the latter greatly improved in quality after a few years maturation and acquired the taste and colour of Malmsey. The colour and taste of Malmsey would come from the oxidation picked up through the oak cask during long-term maturation, and so the beer would have had a subtle sherry-like nuance.

In 1596, the Society of Brewers was established in Edinburgh to control and regulate the malting and brewing trades, and in 1605, brewers and maltsters in Glasgow formed the Incorporation of Maltmen (the Malt Craft).

In 1648, we come across an early reference to brewing in Alloa, when Margaret Mitchell is recorded in the Alloa Parish Records as having brewed and sold her home-brewed ale from her house by the Tron Well.38

It was the merchants and members of the local trades who ran burgh councils, of which the maltmen were the largest group and they exerted considerable political influence. The councils were self-electing and operated longstanding practices and privileges that gave them total control over the town’s affairs. Such political power and control over their fellow citizens inevitably led to much corruption. In 1659, Edinburgh Guildry increased the tax on beer that increased the price of a pint to one penny!

However, the brewers and maltsters were very generous and often came to the assistance of their fellow citizens in time of need. In the Dundee town council minute of 7 December 1669, it is recorded that the maltsters unanimously agreed to pay 2 merks for every boll of malt they brewed to offset the cost of repairs to the town. This was on top of 2 merks Crown duty and their annual membership fees to the Guildry of 40 merks, which was equivalent to £26,13,4d Scots, or £2,4,5?d English.21

In 1690, the Dundee Burgh council again called upon the brewer’s generosity, who agreed to pay 10s Scots (10/-) for every boll of malt brewed for the next eleven years. The trade-off to this agreement was that the brewers who had previously been barred from holding office in the town council could now do so, and that their annual fee to the Guildry was to remain at 40 merks.

In 1693, Edinburgh Town Council persuaded Parliament to levy an additional 2d per pint over and above the King’s Excise on every brewer within the town boundaries. The maltsters and brewers argued that the 2d tax was intolerable and many existing breweries relocated outside the town’s boundaries to escape local taxes. In the same year, the Glasgow magistrates were authorised by Parliament to tax 2d per Scots pint to overcome their debts and burdens, and successive Acts of Parliament saw the tax in force until 1837.

In the early 1700s, the present Traquair House Brewery was built, complete with mash tun and fermenting vessels made from the finest Russian Memel oak. Hops would now be used to flavour and preserve the beer.

In 1701, the Dundee council once more applied for aid from the brewers, who agreed to contribute 7,000 merks annually for the next five years.21 Also, in 1702, Queen Anne sanctioned the town councillors to add an extra 2d on every pint brewed and consumed within the burgh boundaries. This tax was to be used for repairs to the harbour, the town house and the hospital, and was to last for twenty-four years. The Act specifically stated that the tax was not only to be levied on brewers within the burgh, but also those who brewed in the town’s suburbs. In 1706, the price of a pint in Dundee was 20 Scots pennies, which equalled 1 bawbee, or a halfpenny Sterling.

In 1719, Belhaven, Dunbar, Scotland’s oldest continually working brewery, was built on the site of an old Benedictine monastery and the wells dug over 700 years ago survived until 1972.

In 1725, we come across another reference to just how small beer tasted in the Scottish Highlands during the eighteenth century, and it comes from Burt’s Letter from the North of Scotland, by Edmund Burt, a government contractor in the Highlands. Burt does not mention heather, groot or hops, but his description sums up the common ale of the times:

The twopenny as they call it, is their common ale, the price of it is two pence for a Scots pint. The liquor is disagreeable to those who are not used to it, but time and custom will make almost anything familiar. The malt, which is dried with peat, turf, or furzes (Whins) that gives to the drink a taste of that kind of fuel, it is often drunk before it is cold out of a cap, or ‘coif, (Quaich) as they call it.

This is a wooden dish, with two handles, about the size of a tea-saucer, and as shallow, so that a steady hand is necessary to carry it to the mouth, and, in windy weather, at the door of a change I have seen the drink blown into the drinkers face. This drink is of itself apt to give diarrhoea; and therefore, when the natives drink plenty of it, they interlace it with brandy or whisky.14

The ‘change’ referred to is the change-house, or tavern. As the brew was drunk whilst still hot and laced with spirits, it was most likely a spiced ale, or toddy, and the fact that it was drunk at the door suggests that it was a deoch an doruis, a farewell drink. In non-Gaelic speaking localities the Scots also called a farewell drink a ‘stirrup-dram’, which has the same connotations as the English ‘stirrup-cup’. That the brew should induce diarrhoea might suggest that it was brewed with groot, which could be very laxative.

In Dundee in 1726, which was four years before the expiry of the 1702 Act, the town councillors applied for a renewal of the legislation but did not inform the maltsters and brewers and, consequently, the Act was granted for another twenty-five years! In 1756, further secretive extensions to the above Act were secured, with additional extensions in 1781 and 1802. Such taxes were considered punitive and the Maltmen partitioned Parliament, pointing out that the greater part of the beer brewed in the suburbs was consumed within the burgh free of the tax in question, which contradicted the terms of the Act of Parliament of 1702. The main source of the grievance was against the Pleasance Brewing Company (later to become Ballingall’s Pleasance Brewery in 1844) that was sited just outside the burgh boundary, but the bulk of their ales were vended and consumed within the town.21

In 1736, an insulated coal-fired copper was installed at Traquair House brewery, which most likely replaced an open cast-iron one, and the wort was chilled in an open shallow wooden cooler before fermentation in one of three fermenters made from Memel oak.

In 1740, Archibald Campbell established the Argyle Brewery in the Cowgate, Edinburgh, a brewery that made a huge contribution to the reputation of Edinburgh as a brewing centre of note, particularly with Scotch Ale and porter.

After Mary Queen of Scots, the next person of note to visit Traquair House was the Young Pretender, Prince Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie), who took shelter at Traquair in 1745 during the fateful Jacobite uprising against the Hanoverians. After a brief recuperation, and no doubt emboldened by the fearsome Traquair Ale, he bade his farewells to his host, the 5th Earl of Traquair, and as he departed through the Bear Gates legend has it that as he and his entourage slowly disappeared from view the earl swore that the gates would remain closed until a Stuart was restored to the British throne. This was not to be, and after the 1745–46 Rebellion, which culminated in the disastrous battle of Culloden, the gates remained firmly closed to this day. The Bear Gates, or ‘Sleekit Yetts’, so called after the carved stone bears that surmount the gateposts, has guarded ten centuries of the comings and goings of kings and queens. Workers who built the house and gates were paid part of their wages with gallons of Traquair Ale.

After the Civil War of 1745–46, Scotland was at peace, and the next fifty years saw major improvements in agriculture and industry. Until this time virtually every tavern keeper brewed their own ale, but due to industry and the wage economy they saw a major shift to large-scale commercial brewing, and by the early 1850s brewing at Traquair House had ceased.

In 1749, Wm. Younger founded the Abbey Brewery in the grounds of Hollyrood Abbey, and it is often claimed that the move was designed to tap into the pure water to be found there, but as the Abbey Brewery was just outside the town’s boundary, he was not obliged to pay local taxes. Other breweries that were built within the Palace precincts were Robert Younger’s St. Anne’s Brewery in 1854, the City of Edinburgh Brewery (1866–74) that was to become Steel and Coulson’s Croft-an-Righ Brewery, and J. & G. Pendreigh’s Palace Brewery (1865–70).

In Glasgow in 1749, Robert Tennent (future co-owner of Wellpark Brewery) was also a burgess and honourable member of the Malt Craft. Despite this, he was pursued through the Court of Session by the Incorporated Trades of Glasgow for non-payment of local taxes. In his defence he stated that he had kept the White Heart Inn in the Gallowgate for a number of years, where he had carried out his own malting and brewing. Furthermore, he stated that he was tired of paying repeated financial penalties for non-payment of local taxes and appealed to the court to have this stopped. Sitting on the bench, Lord Drummore obviously considered the age-old burghal privileges no longer acceptable and found in Tennent’s favour.20 Six years later, Robert Tennent built the original Saracen’s Head (the ‘Sarry Heid’) using stones from the Bishop of Glasgow’s palace that was derelict and falling down.

The Saracen’s Head was to become one of Glasgow’s most famous and popular taverns, frequented by the wealthy, the literati such as James Boswell and Samuel Johnson, and the aristocratic cock-fighting Duke of Hamilton. It was also the favourite meeting place for the city’s magistrates to hold their celebrated dinners, whilst supping Jamaica punch from a five-gallon china punch bowl decorated with the city’s coat of arms. Is it any wonder, then, that the magistrates found in Tennent’s favour?

By the 1750s, Scottish brewers had established a developing trade with America, Germany, Holland, Poland and wine-drinking Spain, and over fifty-seven barrels were exported annually. Apart from the American colonies, the Baltic ports were fruitful for fledging Scottish brewers. By the middle of the decade exports increased to over 900 barrels.

As the population grew and social conditions improved, areas such as Edinburgh, Alloa and Glasgow developed into major brewing centres. As demand for more beer came from mining and industrial communities, greater demand for good-quality barley resulted in improvements in agriculture, chiefly on the east coast, and East Lothian in particular became known as the grain basket of Scotland. Further north, in Fife, the Mearns, Aberdeenshire and East Ross also became noted for the quality of their barley, although in general Highland barley was grown principally for distillation.

In 1762, George Younger built Alloa’s first public brewery, although other sources mention that he was brewing in Alloa since 1744. In 1792, Robert Knox established a Brewery at Cambus, which means ‘bend on the river’, just west of Alloa. Such was the fame of Knox’s beer that he earned the privilege of suppling George III at Windsor Castle. Later the name changed to the Forth Brewery, and by 1845 Alloa could boast eight breweries producing 88,000 barrels per annum.

With the ongoing problem of brewers dodging local taxes, the Edinburgh City Council retaliated against brewers outside the town’s boundary by introducing a 2/- Scots tax on all brewers’ carts entering the city’s boundaries. The brewers responded by delivering their beer on sleighs, but the council quickly included this form of transport in the tax!

The other bone of contention was that burgh magistrates and landowners had the power to issue a degree called ‘Thirlage’, which was a legal obligation to bind a tenant to grind his malt at a certain mill. The council or landlord also took a toll, or multure, of meal for the privilege of grinding the corn at their mill, which was typically one peck on each boll of grain ground. Those that did not comply with the thirlage were to be punished, as the magistrates deemed fit! Until Thirlage and the landlord’s right to a multure were abolished, a tenant also had to pay the landlord a duty called Brew-creesh for the liberty to brew.