Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

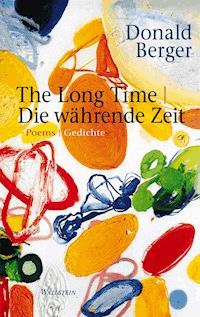

- Herausgeber: Wallstein

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Deutsch

Eine eindrucksvolle Stimme aus New York - erstmals übersetzt ins Deutsche. Die Gedichte von Donald Berger, der 1956 in New York City geboren wurde, haben einen unverkennbaren Ton. Sie sind lakonisch und unruhig zugleich, unterlegt mit höchstem Raffinement. Berger arbeitet mit und im Material der Alltagssprache, er steht in der Tradition der amerikanischen Popdichter wie Allen Ginsberg und ebenso in der einer symbolistischen europäischen Poesie. Seine Gedichte entstehen als Übersetzungen einer an die Sprache und das Sprechen gebundenen Analyse und meiden das direkte Aussprechen von Gefühlen, sie geben nicht vor, eine »Wahrheit" zu verkünden.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 142

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Donald Berger

The Long Time | Die währende Zeit

Poems | Gedichte

Aus dem Englischenvon Christoph König

Wallstein Verlag

for Cindy

All the things I love, come here!

All ihr Dinge, die ich liebe, kommt her!

Gerry Crinnin

The Long Time

It was a long

time. What day

was it? I

didn’t know.

O little while

while you last,

as somebody

who doesn’t know meets

somebody who does,

and the rooms’

crack of wind

tinted glass

across from the

stone-piled well into

the church’s field:

to grip the telephone

with my neck,

over a light

I loved you

Die währende Zeit

Es war eine lange

Zeit. An welchem

Tag? Ich

wusste es nicht.

O kleine Weile,

während du andauerst,

wie einer,

der nicht Bescheid weiß, einen trifft,

der es weiß,

und der Räume

Windriss,

gefärbtes Glas,

von dem

steingefügten Brunnen auf

den Kirchacker hinüber:

das Telefon

mit meinem Hals zu halten,

über einer Lampe

Ich liebte dich

The Wall

The wall has pictures on it.

Why? And there are so many books

on the floor and desk.

There is a pen lying next to an elbow

and a pile of paper at a reach

to the right. In one huge way

that’s all that needs noting

but in another more confused, more modern way,

it’s whatever thought

has fallen, like being promised

to be taken somewhere

you’ve only seen pictures of.

There isn’t anything

planned, the whole day just sort of

swings off into the shadow over there,

swings off to the right over there

next to the picture of the farm.

Die Wand

An der Wand hängen Bilder.

Warum? Und es liegen so viele Bücher

auf dem Boden und dem Schreibtisch.

Da liegt ein Stift neben einem Ellenbogen,

und ein Papierstoß in Reichweite

zur Rechten. In einem großen Sinn

ist das alles, das verzeichnet werden muss,

aber in einem anderen, verwirrteren und moderneren Sinn

ist es jeder Gedanke,

der gefallen ist, wie als Versprechen,

irgendwohin gebracht zu werden,

wovon du nur Bilder gesehen hast.

Gar nichts ist

geplant, der ganze Tag schaukelt gewissermaßen nur fort

in den Schatten dort drüben,

schaukelt fort nach rechts dort drüben

neben das Bild des Bauernhofs.

People’s Stage

I love how you looked on that day.

I didn’t know you and still

Don’t know you,

The day of the walking X’s, no, the walking wheels.

I have to be home before two.

I let in a miniature face.

The shadow under the S-Bahn bridge is cold,

The man-sized graffiti almost a comfort.

Take those thoughts of a hand the fireflower put it

Over the window that reads, in English,

The Unknown Friends.

Volksbühne

Ich mag, wie du an jenem Tag ausgesehen hast.

Ich kannte dich nicht und immer noch

Kenne ich dich nicht,

Am Tag der gehenden Xe, nein, der gehenden Räder.

Ich muss vor zwei zuhause sein.

Ich lasse ein Miniaturgesicht herein.

Der Schatten unter der S-Bahn-Brücke ist kalt,

Das mannshohe Graffiti fast tröstlich.

Nimm jene Gedanken einer Hand, die Feuerblume, setze sie

Über das Fenster, auf dem, auf Englisch, zu lesen ist:

The Unknown Friends.

To Be Where the Sun Is

To be where the sun is,

is that a goal? The roads

curve, the hills lift, the day

on the side of the road.

Honestly to think of

them then, to want to call

out to the north and east

both, at the same time,

human, sworn. What will my

face want, what? What I see

has a hand In it. What

will be my Idea to

wait with me, What I don’t

know What will be my day?

Who’ll know, My nerve set of

six muscles In each of

my eyes, My brain in Two

halves, sounds recorded at the

sides. Speech at the front.

The cables do I Know

the difference Between sight

and sound. The ear, hinged chain

of bones, the head I Smile

with it, angstroms 4 to

eight Thousand violet to

red. What else Will I think,

(while) there? Will senses be

enough, will fall Be enough,

will clouds? Will light stay In my

eyes till gone? Of something

to write or write with, ways,

Words to say if I

one, brightness, Where there’s Bright-

ness in my eyes. Will it Be

enough, will it? What if

I see some person and

Words become this way,

certain, intense. Not

only but the throat Of

what should it Touch the top.

Both eyes at The same thing.

By the lips not only food

but the start of sound. Who

is it? Who walks with his

feet on the walk it’s who

I know, who I think’s what’s

the window, who’s waiting For

everything like a bus

to come. Now I’ll wait, I’ll

act now I’ll form.

Zu sein, wo die Sonne ist

Zu sein, wo die Sonne ist,

ist das ein Ziel? Die Straßen

machen eine Kurve, die Hügel heben sich, der Tag

am Straßenrand.

Ehrlich, an sie

dann zu denken, ausrufen zu wollen

nach Norden und Osten

gleichermaßen, gleichzeitig,

menschlich, verschworen. Was wird mein

Gesicht wollen, was? Was ich sehe,

hat eine Hand Im Spiel. Was

werde ich mir dabei Denken,

wenn ich mit mir warte, Was ich nicht

weiß Welcher wird mein Tag sein?

Wer wird es wissen, Mein Nervenbündel

aus sechs Muskeln In jedem

meiner Augen, Mein Hirn in Zwei

Hälften, Geräusche an den Seiten

aufgenommen. Rede vorne.

Die Kabel Kenne ich

den Unterscheid Zwischen Bild

und Ton. Das Ohr, Knochen-

kette im Scharnier, der Kopf, mit dem ich

Lächle, Ångstrom 4 bis

acht Tausend violett bis

rot. Was Werde ich sonst noch denken,

(während ich) dort (bin)? Werden Sinne

ausreichen, wird der Herbst Ausreichen,

werden es Wolken? Wird das Licht In meinen

Augen bis zum Ende leuchten? Von etwas,

was ich schreibe oder mit dem ich schreibe, Wege,

Worte, zu sagen, ob Ich

einer, Helligkeit, Wo Hellig-

keit in meinen Augen ist. Wird es

genügen, wird es? Was aber, wenn

ich einen Menschen oder

Worte auf diesem Weg entstehen sehe,

gewiss, stark. Nicht

nur, aber die Kehle Von

was, sollte es den Gipfel Erreichen.

Beide Augen auf Dasselbe gerichtet.

An den Lippen nicht nur Essen,

sondern der Beginn von Lauten. Wer

ist es? Wer mit seinen

Füßen auf dem Gehweg geht, ist der, den

Ich kenne, der, von dem ich denke, er sei, was

das Fenster ist, der Auf

alles wie auf einen Bus wartet,

der kommen soll. Nun werde ich warten, handeln

werde ich nun werde ich gestalten.

On the Thing

Can you expect special things to happen when you

Know that nothing great has ever happened before?

You can expect special things to happen, you can have

Breathing room, and wine, at no one else’s expense.

The road to the back of the room, where all the laughter

Is, seems so wide, I do not have to tell you how even

Wider it will become. So if you’re not tired, people can

Go there, and ask for a drink and enjoy whatever life

Without pretending. I’ve seen it, I saw it myself. The

Rays were those of electric lights but such a poverty

Went, and still goes, unnoticed. When I looked up,

It was three in the morning, a huge crowd of different

Colors was gathering. It was interesting, and people

Spoke to you face-to-face whether you wanted them

To or not. I remember feeling pickled with all kinds

Of feeling for it, in the back room, on the small street,

Wherever. Can you imagine looking at it for fourteen

Straight hours and never forgetting what you had to go

Back to? But it wasn’t dangerous, so unlike sugar or

Tobacco or meat it wasn’t funny. Fourteen times in

Six days I was forced to write to them about it, on bland

Postcards with pictures of grass on them, or maybe

A flower. By the grace of god it seemed not to punish

Anything for being there without listing, shoving. One

Guy tried to sell me a knife, and another offered to buy

It back from me, after I bought it. The moon had an un-

Documented shape to it. It was lathered. Steam tried

Reaching up to it, refusing to hide its hands. Soon we

Got tired of wishing for things, and didn’t love it, refusing

Even this last want, for someone to drive up and say we

Didn’t have to do anything anymore, and that the place

Looked good, spreading itself out under us or above us.

Über das Ding

Darf man besondere Ereignisse erwarten, wenn man

Weiß, dass nichts Großartiges sich je zuvor ereignet hat?

Man darf besondere Ereignisse erwarten, man kann

Atemraum und Wein haben, auf niemand anderes Kosten.

Der Weg hinten in das Zimmer, wo das ganze Gelächter

Herkommt, scheint so breit, ich muss dir nicht sagen, um wieviel

Breiter sogar er werden wird. Wenn du also nicht müde bist, können die LeuteDorthin gehen und einen Drink bestellen

und jedwedes Leben genießen,

Ohne sich zu verstellen. Ich habe es gesehen, ich sah es mit eigenen Augen. DieStrahlen kamen von elektrischen Lampen, doch eine solche ArmseligkeitGing, und geht immer noch, unbemerkt vorüber. Als ich aufsah,War es drei Uhr früh, eine große Menge verschiedener

Farben versammelte sich. Es war anregend, und LeuteSprachen dich direkt an, ob du dasWolltest oder nicht. Ich erinnere mich mit allen möglichen Gefühlen dabeiDrangsaliert zu sein, im Hinterzimmer,

zur engen Straße hin,

Wo auch immer. Kannst du dir vorstellen, vierzehnGanze Stunden zuzusehen und niemals zu vergessen, worauf duZurückgreifen musstest? Aber es war nicht gefährlich, ganz anders als Zucker oder

Tabak oder Fleisch war es kein Vergnügen. Vierzehnmal während

Sechs Tagen war ich gezwungen, ihnen darüber zu schreiben, auf fadenPostkarten mit Fotos von Gras darauf, oder vielleichtEiner Blume. Bei Gott, es gab offensichtlich keine Strafe dafür,Dass man da

war, ohne zu wanken, zu drängeln. Ein

Typ versuchte, mir ein Messer zu verkaufen, und ein anderer bot an,

Es von mir zurückzukaufen, nachdem ich es kaufte. Der Mond gab eine un-Registrierte Gestalt ab. Er war eingeschäumt. Dampf versuchteZu ihm hinaufzureichen und lehnte es ab, seine Hände zu verbergen.Bald hatten wir

Genug davon, uns Dinge zu wünschen, und mochten es nicht, lehnten Sogar diesen letzten Willen ab, dass jemand vorfahre und sage, wir

Müssten überhaupt nichts mehr tun, und dass der Ort

Gut aussähe, wie er sich unter uns und über uns ausdehnte.

House of Fun

When what I think speaks to what I will say,

And the lives of a question splatter over the sight of things,

The news of light of song are in line for once, and the voice

Doubles back for the sighing, its notes rich as a birth.

When what lacks finds nothing in sung prayers that are heard,

A large and active wait sits hard in turning toward its intention,

And how you seem goes off into space, emotion draws no screen

over the words,

What comes is a fair amount closer to absence,

The shock of not ever minding, loving to rest again.

So if the people around you don’t become these symbols

for darkening change

And you can float for a time, listless and wet with the pitch

Of whoever is calling, time can lie down with you then,

And laughter work on you, throwing your head up.

Haus des Vergnügens

Wenn das, was ich denke, zu dem spricht, was ich sagen werde,

Und die Leben einer Frage auf den Anblick von Dingen spritzen,

Dann stehen die Nachrichten von Licht, von Gesang ausnahmsweise einmal aufgereiht, und die StimmeMacht um des Seufzens willen

kehrt, ihre Töne voll wie eine Geburt.

Wenn das Fehlende nichts findet in gesungenen Gebeten, die man hört,

Hat ein großes und tätiges Warten es schwer, sich der eigenen Absicht zuzuwenden,Und was du zu sein scheinst, steigt in das All auf, das Gefühl zieht keine Blende über die Wörter,Was kommt, ist um einiges dem Wegsein näher,Der Schock, sich niemals mehr

um das Rasten zu kümmern, es zu schätzen.

Wenn also die Leute um dich herum nicht zu diesen Symbolen des

dunkelnden Wandels werden

Und du eine Zeit lang treiben kannst, antriebslos und nass vom

Eintauchen

Dessen, wer auch immer ruft, kann sich die Zeit mit dir dann hinlegen,

Und das Lachen sich entfalten, deinen Kopf hochwerfend.

Annisquam

Afraid to swim, some of them walked

on top of the water, saying I’m sorry,

I’m sorry under their breath,

the trees always moving, the flag whose noise

kept the baby up crying,

the arrangement of rocks much smaller than humans

still too heavy to carry

but nevertheless looking like they’d been placed there.

And above and swinging around to the right,

houses too big to be seen completely

but enough porches and windows

to indicate sweet mass, evenings when someone

somewhere must have been unhappy

and gone out there to think before sun-up.

The baby tries walking into the ocean

alone. You can see sand on the bottom, little else,

a few fists of weed that pop between the fingers.

Here, you don’t have to try

figuring out how you got there.

It’s too obvious to prevent you from doing

the first things you think:

throwing rocks, humming on snails

to get them to come out, swinging each other

waist-deep in the foam of someone else’s water.

Annisquam

Aus Angst vor dem Schwimmen gingen einige

auf dem Wasser und sagten, es tut mir leid,

Es tut mir leid, kaum hörbar,

die Bäume immer in Bewegung, die Fahne, durch deren Lärm

das Baby wach war und schrie,

das Arrangement von Felsen, die viel kleiner waren als Menschen

dennoch zu schwer zum Tragen

aber trotzdem aussahen, als hätte man sie dort hingelegt.

Und darüber und sich nach rechts herumschwingend,

Häuser, zu groß, um sie ganz zu sehen

aber ausreichend Veranden und Fenster,

um süße Masse anzudeuten, Abende, als irgendwer

irgendwo unglücklich gewesen sein muss

und dorthinaus gegangen, um vor Sonnenaufgang nachzudenken.

Das Baby versucht, allein in das Meer

zu gehen. Du kannst Sand auf dem Grund sehen, sonst wenig,

einige wenige Fäuste voll Tang, der zwischen den Fingern platzt.

Hier brauchst du nicht versuchen

herauszufinden, wie du dorthin gekommen bist.

Es ist zu offensichtlich, als dass es dich davon abhalten könnte,

die ersten Dinge zu tun, die du denkst:

Steine zu werfen, auf Schnecken zu summen,

damit sie herauskommen, einander zu schwenken

bis zur Hüfte im Schaum des Wassers von jemandem anderen.

Dinner in the Sun

after Eli Gottlieb’s The Boy Who Went Away

Someone might think that because New Jersey is a relatively easy

concept

Of the author, its characters too charged with the beach and its

words nasty and pelletlike,

Instead of building on their own a passion for complex fully

developed human beings –

Do you think the decision is accurate?

Is the boy merely representing degrees of calm?

Which characters are more or less openly smooth, or square?

Does anyone guess that God is simply turning coldly away

Or crouched in the basement in front of his workbench in favor

of loving a cigar?

Does Denny (the brother) ever seem torn by loving his shortcuts?

Does Harta, his mom, ever seem more horn-haired than her son?

If it’s true, does someone think the author wanted to feel all this, or

do we respond to the characters

Distantly now that they’re gathered into a headlock?

“I thought everything about grown-up life was like furniture,” Max,

the father, tells his son, “solid and heavy and forever and ever …

Hoo-boy, was I wrong,” he says. Needing this book in the late

Twentieth century, when we forget how hot it gets, does the

narrator’s spywork, his look at himself, seem coupled

properly with the right moment?

Does anyone think the boy is oblivious as much to his robin’s egg

blue as he is the neon heat of his adjective?

To powerful chitterings of waters in general?

The Jersey men discuss Minkoff, the doc, pages before the reader

actually sees him raise his hands, then put a fist in front

of his mouth.

Why does someone sense God chose to wobble, notebook in hand?

What do Denny and Derwent’s reactions to Jersey show us about

their surveillance emplacements, about their mail, delivered

by someone who seemed to float?

Before his rays of light are removed from him, does Denny resort to

the voice of a wounded animal?

Is he a muscular character? Does his wind not touch itself with a fist?

How does the author peer through the hole?

What does Denny’s opinion of danger–that he enjoys it for its

“splinters of wood whittled into likenesses of long-faced

men”–eventually do for him?

At the center of the book once the boy’s force is ultimate, does

Denny seem in any way a familiar thick feeling?

God himself rarely stirs, but the author wiggles his ears with

a silvery laugh.

What does anyone guess the book is saying about the brother’s

radiating outward, while cutting towards mirrors?

How do the stems of the boy, Harta, Max and Denny reflect

(refract?) on the burning cone?

Would God have considered it a happy ending for Denny if, as

begun at the end, Sabina had laughed and started lifting him?

Or if she had ended up laughing indefinitely, and still “extending a

long finger at the carrot sticks,” as she’d always done, before