Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

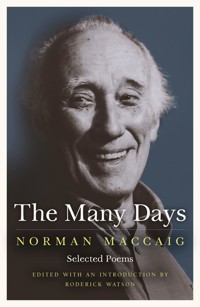

First published in 2010 to mark the centenary of Norman MacCaig's birth, The Many Days aims to strike a balance between representing the much-loved poems that any reader would expect to find in a selected MacCaig, and other less familiar verses. The collection is arranged to show the range of the poet's work in all its variety, from his love of nature and the landscape of the North West Highlands to his life in Edinburgh; from his care for animals and human friendship, to his moments of joy and grief, creative delight and occasional creative dread. Time and again MacCaig returns us to that good place we know as the world, but hardly ever seen so clearly as we do in these marvellous poems.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 98

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Many Days

This ebook edition published in 2013 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd Revised edition published 2013

Poems copyright © the estate of Norman MacCaig Introduction copyright © Roderick Watson, 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-780-6 Print ISBN: 978-1-84697-171-6

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Contents

Introduction

Ineducable Me

Ineducable me

Climbing Suilven

Sleeping compartment

Lord of Creation

Private

Go away, Ariel

Patriot

Small lochs

London to Edinburgh

Portobello waterfront

Journeys

On a beach

Bright day, dark centre

On the pier at Kinlochbervie

Emblems: after her illness

Sargasso Sea

By the Three Lochans

Hugh MacDiarmid

After his death

Grand-daughter visiting

To be a leaf

Between mountain and sea

One of the Many Days

One of the many days

Feeding ducks

Goat

Byre

Fetching cows

Blind horse

Frogs

Basking shark

Wild oats

Sparrow

Blackbird in a sunset bush

Ringed plover by a water’s edge

Dipper

Toad

Blue tit on a string of peanuts

My last word on frogs

Our neighbour’s cat

Gin trap

Likenesses

Likenesses

Instrument and agent

Summer farm

Linguist

Leaving the Museum of Modern Art

Painting – ‘The Blue Jar’

Helpless collector

No choice

Recipe

Also

No end to them

Landscape and I

Among Scholars

Among scholars

Midnight, Lochinver

Crofter’s kitchen, evening

By Achmelvich bridge

Neglected graveyard, Luskentyre

Moment musical in Assynt

Two shepherds

Aunt Julia

Uncle Roderick

The Red Well, Harris

Country dance

Return to Scalpay

Praise of a road

Praise of a collie

Praise of a boat

Praise of a thorn bush

Fishermen’s pub

Off Coigeach Point

Old Highland woman

Two men at once

Old Maps and New

Old maps and new

High Street, Edinburgh

Celtic cross

Crossing the Border

Two thieves

A man in Assynt

Old Edinburgh

Battlefield near Inverness

Rewards and furies

Queen of Scots

At the Loch of the Pass of the Swans

Characteristics

From My Window

From my window

November night, Edinburgh

Edinburgh courtyard in July

Hotel room, 12th floor

Last night in New York

Antique shop window

Milne’s Bar

Gone are the days

Neighbour

University staff club

Edinburgh stroll

Five minutes at the window

Foggy night

Balances

Balances

Equilibrist

Spate in winter midnight

July evening

Visiting hour

Assisi

Smuggler

Interruption to a journey

Vestey’s well

Notations of ten summer minutes

Intruder in a set scene

Adrift

Sea change

Two skulls

So many summers

Sounds of the Day

Small boy

Old poet

In That Other World

In that other world

Loch Sionascaig

Descent from the Green Corrie

Memorial

Old man thinking

From Poems for Angus

Notes on a winter journey, and a footnote

A.K. MacLeod

Praise of a man

Angus’s dog

In memoriam

Her illness

Myself after her death 1, 2, 3

Found guilty

A Man in My Position

A man in my position

Party

Estuary

Song without music

Names

Incident

Perfect evening, Loch Roe

Water tap

Index of Poem Titles

Biographical Notes

Introduction

‘His poems are discovered in flight, migratory, wheeling and calling. Everything is in a state of restless becoming: once his attention lights on a subject, it immediately grows lambent.’ In this description, Seamus Heaney gets to the heart of Norman MacCaig’s verse. Time and again MacCaig brings us to a moment of evanescent delight, to a humane epiphany of love and mortality in that good place we know as the world around us, but hardly ever see so clearly. MacCaig’s clear-sightedness is almost a matter of creative moral duty (one thinks of him as a conscientious objector during the Second World War). His imagination, in turn, allows us to see the world afresh, newly minted with surprise and delight: a goat ‘with amber dumb-bells in his eyes’, or that cow ‘bringing its belly home, slung from a pole’, or the thorn bush that traps stars in ‘an encyclopaedia of angles’.

MacCaig’s metaphors are well known and loved by the thousands of readers and listeners who enjoy his work. In poem after poem he leads us to make the leap that will reveal the connection, but also the disconnection, between the metaphor and the thing itself. The poet is always aware of the gap, sometimes ironically, often humorously, and sometimes – as an artist – in despair of ever really bridging it. Thus there are darker and more personal poems in this selection that speak of moments like the ‘ragged man’ waiting for him in the poem ‘Bright day, dark centre’, or the need ‘to feel the world like a straitjacket’ in ‘On the pier at Kinlochbervie’, where the strain of the poem’s opening metaphor about ‘a bluetit the size of the world’ pecking the stars out ‘one by one’ speaks for a moment of personal terror by turning one of his fond and familiar creative leaps into something simultaneously ‘ludicrous’ and menacing.

Such dichotomies are never far from the surface in MacCaig, and yet the landscape he shows us in his work, like the peaceable kingdom of animals and people and mountains that he found in Assynt, is everywhere, finally, infused with a caring attention. Seamus Heaney sees a link with early Irish verse and the Scottish Gaelic tradition in ‘the clarity of image, the sensation of blinking awake in a pristine world, the unpathetic nature of nature in his work’, and MacCaig specifically invoked that tradition with the praise poems he wrote for a road, a collie, a boat, a thorn bush – humble subjects, so radiantly realised.

The collective achievement of MacCaig’s lyrics is unprecedented in modern poetry. I cannot think of any other poet anywhere who has so faithfully and so persistently explored the act of noticing, and the nature of being in the world, through the thousands of epiphanic moments that are his poems, in a creative career of sixteen collections and more than fifty years. Such stern commitment to a single craft, and such generous devotion to the illumination of the world, has an almost monk-like quality to it, although MacCaig – no lover of organised religion – would have hated the comparison. But if you think of it as a secular devotion, and remember the strange little monsters to be found in the margins of the pages of the Book of Kells, then perhaps the analogy will hold.

It has not been easy to make a selection from the treasure house of the complete poems. I was helped in this task and owe a debt of thanks to Tom Pow, Alan Taylor and Ewen McCaig. Our meetings were lively as we tried to strike a balance between representing the much-loved poems that any reader would expect to find in a selected MacCaig, and choosing less familiar verses. The titled sections in this book are my way of perhaps providing new contexts for even the most well-known verses, and for allowing MacCaig’s own lines to reveal common themes and preoccupations in his work. Thus each section starts with a title poem that sets the scene for the selection to follow: Among Scholars, for example, introduces a series of poems that revolve around MacCaig’s regular sojourns in Achmelvich and the west of Scotland, while the poems in From My Window speak of his time in cities and most especially in Edinburgh. The section entitled Old Maps and New reminds us that MacCaig has often reflected – directly and indirectly – on Scottish history, not least in his long poem ‘A Man In Assynt’, whose personal-political focus must be included in any proper account of his work. The verses in Likenesses reflect – sometimes self-critically – on the poet’s own penchant for metaphor and have insights to offer on the nature of the creative process itself. Under Ineducable Me we find poems of a more personal aspect, humorous and sometimes disturbingly painful, from a writer who had nothing but contempt and distrust for ‘gush’ and the so-called confessional poetry of the 1960s. The poems of One of the Many Days bring us to the Edenic world of creatures and landscapes that is the setting for some of Norman’s most popular lyrics, just as those in Balances remind us that the human world has a darker side to it that no poet can escape or ignore. And if the prevailing spirit of MacCaig’s achievement is still one of surprise and delight, then the reflections on death and personal loss from In That Other World remind us that intimations of mortality underlie the beauty of all existence, and have powered the heart of every fine lyric that has ever been written. But in the end for MacCaig, and not just for the poems that make up the final section, A Man in My Position, the first and the last word, clear-eyed, sardonic or tender, has always been love.

But no editorial categorisation can ever do justice to the way MacCaig’s themes interpenetrate each other with surprise, humour, terror and delight at every turn of every line. Nor are these sections meant to suggest otherwise; rather they are a way of encouraging MacCaig’s own poems to speak for themselves and (in this arrangement) among themselves, to set up the best kind of creative dialogue, section to section, poem to poem.

Everything speaks to everything else in MacCaig’s work and, despite those wonderful frogs, he never wrote simply ‘an animal poem’ in his life.

Roderick Watson

Ineducable Me

Ineducable me

I don’t learn much, I’m a man

of no improvements. My nose still snuffs the air

in an amateurish way. My profoundest ideas

were once toys on the floor, I love them, I’ve licked

most of the paint off. A whisky glass

is a rattle I don’t shake. When I love

a person, a place, an object, I don’t see

what there is to argue about.

I learned words, I learned words: but half of them

died for lack of exercise. And the ones I use

often look at me

with a look that whispers, Liar.

How I admire the eider duck that dives

with a neat loop and no splash and the gannet that suddenly

harpoons the sea. – I’m a guillemot

that still dives

in the first way it thought of: poke your head under

and fly down.

Climbing Suilven

I nod and nod to my own shadow and thrust

A mountain down and down.

Between my feet a loch shines in the brown,

Its silver paper crinkled and edged with rust.

My lungs say No;

But down and down this treadmill hill must go.

Parishes dwindle. But my parish is

This stone, that tuft, this stone

And the cramped quarters of my flesh and bone.

I claw that tall horizon down to this;

And suddenly

My shadow jumps huge miles away from me.

Sleeping compartment

I don’t like this, being carried sideways

through the night. I feel wrong and helpless – like

a timber broadside in a fast stream.

Such a way of moving may suit

that odd snake the sidewinder

in Arizona: but not me in Perthshire.

I feel at rightangles to everything,

a crossgrain in existence. – It scrapes

the top of my head and my footsoles.

To forget outside is no help either –

then I become a blockage

in the long gut of the train.

I try to think I’m an Alice in Wonderland

mountaineer bivouacked

on a ledge five feet high.

It’s no good. I go sidelong.

I rock sideways ... I draw in my feet

to let Aviemore pass.

Lord of Creation

At my age, I find myself

making a mountainous landscape

of the bedclothes. A movement

of knee and foot

and there’s Cul Mor and a hollow

filled with Loch Sionascaig.

I watch tiny sheep stringing along

a lower slope.

Playing at God.