Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Carcanet Poetry

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Wordsworth's 'meanest flower that blows' suggested to him 'thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears'. The lyrics, elegies, songs and ghazals in Mimi Khalvati's book pay attention to things the imagination generally disregards, an attention that is concentrated, intense and unapologetically Romantic. Hers is the true voice of feeling, undeflected by irony or self-deprecation. There is rapture in these poems as well as a tragic sense: nature, childhood, motherhood and family relationships all have a double valency, a give and take, to which Khalvati witnesses with a feeling sharpened by love and grief.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 53

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

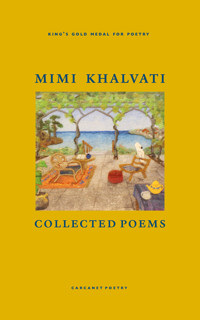

MIMI KHALVATI

The Meanest Flower

for Judith and Ruth

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements are due to the editors of the following publications in which some of these poems or earlier versions have appeared:

Acumen, Agenda, Ashkar Parva, Atlas, Cimarron Review, 100 Poets against the War (Salt 2003), Images of Women (Arrowhead Press 2006), In the Company of Poets (Hearing Eye 2003), Foolscap Broadsheets, Launde Bag, Let Me Tell You Where I’ve Been (The University of Arkansas Press 2006), Magma, Modern Poetry in Translation, Morning Star, Nûbihar, PN Review, Poems in the Waiting Room, Poetry Calendar (Alhambra Publishing 2006 & 2007), Poetry International (USA), Poetry London, poetry p f, Poetry Review, Scintilla, Siècle 21, Staple, The Book of Hopes and Dreams (bluechrome publishing 2006), The North, The Other Voices Anthology, The Poet in the Wall (univers enciclopedic 2007), The Times, Velocity (Black Spring Press 2003), Wasafiri, Women’s Work: Modern Women Poets Writing in English (Seren 2007).

‘Come Close’ was commissioned by Poetry International, South Bank Centre, and also set to music by Bruce Adolphe in his song cycle Songs of Life and Love, premièred in Portland, Oregon; ‘Ghazal: The Children’ was commissioned by the Barbican Centre and broadcast on Radio 2 The Word; ‘Ghazal: My Son’ was broadcast on BBC World Service ‘A Thousand Years of Persian Ghazal’; ‘Ghazal’ (for Hafez) was included in Oxfam’s CD Life Lines and a selection of poems is published on CD by the Poetry Archive.

I am grateful to the Royal Literary Fund for a fellowship at City University and to the International Writers Program in Iowa which I attended as a William Quarton fellow in 2006.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

I The Meanest Flower

The Meanest Flower

Ghazal: It’s Heartache

Ghazal: Lilies of the Valley

Ghazal: The Candles of the Chestnut Trees

Ghazal (after Hafez)

Ghazal: To Hold Me

Ghazal: Of Ghazals

II The Mediterranean of the Mind

The Mediterranean of the Mind

The Middle Tone

Al Fresco

Scorpion-grass

Water Blinks

The Valley

Overblown Roses

Come Close

Soapstone Creek

Soapstone Retreat

On a Line from Forough Farrokhzad

III Impending Whiteness

Impending Whiteness

Amy’s Horse

The Year of the Dish

Motherhood

The Robin and the Eggcup

Song for Springfield Park

On Lines from Paul Gauguin

Magpies

Ghazal: The Servant

Ghazal: The Children

Ghazal: My Son

Signal

Sundays

Tintinnabuli

Notes and Dedications

About the Author

Also by Mimi Khalvati from Carcanet Press

Copyright

I The Meanest Flower

The Meanest Flower

i

April opens the year with the first vowel,

opens it this year for my sixtieth.

Truth to tell, I’m ashamed what a child I am,

still so ignorant, so immune to facts.

There’s nothing I love more than childhood, childhood

in viyella, scarved in a white babushka,

frowning and impenetrable. Childhood,

swing your little bandy legs, take no notice

of worldliness. Courtiers mass around you –

old women all. This is your fat kingdom. The world

has given you rosebuds, painted on your headboard.

Measure the space between, a finger-span,

an open hand among roses, tip to tip,

a walking hand between them. None is open.

ii

Cup your face as the sepals cup the flower.

Squarely perched, on the last ridge of a ploughed field,

burn your knuckles into your cheeks to leave

two rosy welts, just as your elbows leave

two round red roses on your knees through gingham.

How pale the corn is, how black your eyes, white

the whites of them. This is a gesture of safety,

of happiness. This is a way of sitting

your body will remember: every time

you lean forward into the heart of chatter,

feeling the space behind your back, the furrow

where the cushions are, on your right, your mother,

on your left, your daughter; feeling your fists

push up your cheeks, your thighs, like a man’s, wide open.

iii

The nursery chair is pink and yellow, the table

is pink and yellow, the bed, the walls, the curtains.

The fascia, a child’s hand-breadth, is guava pink,

glossy and lickable. It forms a band

like the equator round the table. The equator

runs down the chair-arm under your arm, the equator

is also vertical. The yellow’s not yellow

but cream, buttery, there’s too much of it

for hands as small as yours, arms as short,

to encompass. Let tables not defeat me,

surfaces I can’t keep clean, tracts of yellow

that isn’t yellow but something in between

mother and me be assimilable.

Colours keep the line to memory open.

iv

Here where they’re head-high, as tall as you, will do.

This is the garden in the garden. Here

where they’re wild and thin and scraggy but profuse

such as those ones there, these ones here, no one

looking, no one within a mile, you’ll find

flowers to pick and to press but before their death

at your hands, such small deaths they make of death

a nonsense and so many who would notice?

with the best ones, flat ones, left till last, take time

to take in the garden, the distance from the paths,

the steps and the terrace crunching underfoot.

Soon you’ll hear a whistle. The garden is timeless.

Time is in the refuse, recent, delinquent.

Go as you came, leaving it out in the open.

v

As if they were family, flowers surround you.

As if they were a story-book, they speak.

They speak through eyes and strange configurations

on their faces, markings on petals, whiskers,

mouth-holes and pointed teeth. They are related

to wind. Wind is a kind of godfather, high up

in the branches. They’re willing you to listen

to them, not him. Even now you’re too old

– though too young in reality for most things –

to understand their language. Once, you could.

You can feel the burn in the back of your mind,

as you hold their gaze, where the meanings are,

too far away to reach. What creature is it

that can stand its ground, keep its mind so open?

vi

There are stars to accompany you by day.

After you’ve gone to bed, they fall to earth

like dew but, to accommodate that dew,

presumably fall first. You’ve seen the fluff

from your blanket, a blue cloud in the air;

hooded in your cloak with its scarlet lining,

walking between the pine trees late at night

seen stardust so fine you took it for granted