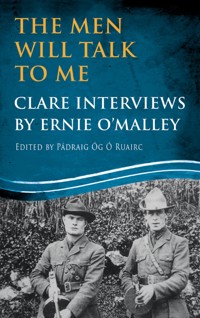

The Men Will Talk to Me: Clare Interviews E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Ernie O'Malley Series

- Sprache: Englisch

This book contains interviews with members of the IRA's Mid Clare and East Clare Brigades. It includes details of the Rineen Ambush, which was, at that time, the largest and most successful operation that the IRA had conducted against the RIC. It also includes an eyewitness account of the reprisals in Miltown Malbay carried out in revenge for the ambush and a fascinating account of IRA operations in Ennis during the War of Independence, including details of Republican sympathisers within the RIC garrison who provided the IRA with information, and the activities of local loyalists who assisted the British forces. There is also an account of the 'Scariff Martyrs', who were killed by members of the RIC Auxiliary Division on Killaloe Bridge. The Civil War also features prominently, with Paddy MacMahon discussing his capture during the 'Battle of the Four Courts' in Dublin.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 335

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MERCIER PRESS

Cork

www.mercierpress.ie

www.mercierpress.ie

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Liz Gillis, 2016

ISBN: 978 1 78117 418 0

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 419 7

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 420 3

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

For my parents, Pat and Monica

Map showing the brigade and battalion divisions and the main towns of Co. Clare.

Acknowledgements

The weekends of my boyhood were spent in west Clare and it was probably from my late grand-uncle, Miko Hayes, that I first heard stories of the Rineen Ambush, the Black and Tans and the Republican struggle in Clare. Visits to his home in Shanaway East, Miltown Malbay, inspired my love of history, archaeology and folklore, and for that I will always be grateful. Likewise I also owe a great debt to his sister, Mary ‘Nana’ Murrihy (née Hayes) of Knockbrack, Miltown Malbay, who had a wealth of stories and was always eager to share them with me.

I also wish to thank Cormac K. H. O’Malley, custodian of the O’Malley notebooks, who realised the value and importance of his father’s research and was eager to share his archive with the public, and Dr Tim Horgan, who started the ball rolling on the transcription of the O’Malley notebooks – without his knowledgeable assistance and advice the transcription of O’Malley’s Clare interviews would not have been possible.

Thanks also to Colin Hennessy, grandson of O’Malley interviewee Séamus Hennessy, who has always been generous with his time and information; Fintan MacMahon, son of O’Malley interviewee Michael MacMahon, who didn’t hesitate to help when I approached him as a complete stranger seeking his assistance; the McDonnell family from Burgess, Tipperary, who shared with me the stories of ‘Black Paddy’ McDonnell, ‘the Brigadier’, and their family’s role in the Republican struggle; Dr John O’Callaghan, one of the first pioneers to successfully decipher and publish O’Malley’s handwriting; Tom Toomey, a brilliant historian and loyal friend to whom I frequently turn for advice; Johnny White, a great neighbour and one of nature’s gentlemen; the O’Gorman family of Moy, Lahinch, especially the late Michael O’Connell, who shared with me a wealth of stories and information about the history of west Clare; P. J. Donnellan of Toureen, Miltown Malbay, who gave me some valuable insights into the War of Independence and Civil War in Clare; and Eoin Shanahan, who assisted me with queries relating to the IRA’s West Clare Brigade.

The staff of the Irish Military Archives provide a top-class service, as do the staff of the British National Archives at Kew in London – their efficient service makes research there a pleasure. Mike Maguire of the local studies section in Limerick City Library, his counterpart Peter Byrne in the Local Studies Centre in Ennis and Maureen Comber of the Clare County Library were all extremely helpful.

Tony MacLoughlin, the most affable bookstore owner in Dublin, makes every visit to his shop on Parnell Street memorable. Sean O’Mahony and the 1916–21 Club have always given valuable assistance and support to my endeavours. The members of the Meelick-Parteen and Cratloe War of Independence Commemoration Committee (Councillor Cathal Crowe, Tom Gleeson, Eamon O’Halloran, Jody O’Connor, Ger Hickey and Pat McDonough) have done invaluable work in preserving and promoting the history of the IRA’s East Clare Brigade.

Thanks to Dr John Borgonovo and Dr Andy Bielenberg of University College Cork, two of Ireland’s hardest-working historians; Dr Tomás Mac Conmara, who is probably the best historian working in Clare today and certainly one of the finest in the country; Dr Billy Mag Fhloinn, with whom it is always a pleasure to discuss Irish history and heritage; Cormac Ó Comhraí, an exceptionally talented historian and a great friend; and Liam Hogan, a restless new historian hungry for the truth.

Joe Laffan, Seamus Cantillon, Aidan Larkin, Karl Walsh, Kieran O’Keefe and all the Caherdavin gang; John White, Gavin O’Connell, Cathal McMahon and all the lads from Meelick; and of course the ‘usual suspects’ – Chris Coe, Sean Patrick Donald, Dara Macken, William Butler and Patrick Fleckenstein – I couldn’t ask for better friends.

Thanks to my publishers Mercier Press, especially Wendy Logue and Mary Feehan, who have the unenviable job of trying to turn my disjointed, grammatically flawed and misspelled manuscripts into books. And a special thank you to the Sheehy family of Clonmeen House, Banteer, Co. Cork.

Finally thanks to my parents, Pat and Monica, for their financial assistance during my time at university, and to my sister Deirdre and my brother Kevin for their friendship and support. Lastly, and most importantly, thanks to my wife Anne Maria for all the happy years she has given me, and to my son, Tomás, who helps remind me that there are far more important things in life than writing history books.

Abbreviations

Auxie/Auxies Auxiliary Division of the RIC

BMH Bureau of Military History

D/M Director of Munitions

EOM Ernie O’Malley

IPP Irish Parliamentary Party

IRA Irish Republican Army

IRB Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Joy Mountjoy Prison, Dublin

NAUK National Archives, Kew, UK

O/C Officer Commanding

PMCILI Provisional Military Court of Inquiry in Lieu of Coroner’s Inquest

RAF Royal Air Force

RIC Royal Irish Constabulary

TD Teachta Dála

UCDA University College Dublin Archives

V/C Vice-Commandant

WS Witness Statement

Preface

Introducing the Ernie O’Malley Military Interviews

Cormac K. H. O’Malley

Though born in Castlebar, County Mayo, in 1897, Ernie O’Malley moved to Dublin with his family in 1906 and attended CBS secondary school and university there. After the 1916 Easter Rising he joined the Irish Volunteers while pursuing his medical studies, but in early 1918 he left home and went on the run. He rose through the ranks of the Volunteers and later the Irish Republican Army, and by the time of the Truce in July 1921 at the end of the War of Independence, or Tan War as it was known to him, he was commandant-general of the 2nd Southern Division, which covered parts of Limerick, Tipperary and Kilkenny, with over 7,000 men under his command.

O’Malley was suspicious of a compromise being made during the peace negotiations which resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921, and reacted strongly against the Treaty when it was announced. As the split developed in the senior ranks of the IRA in early 1922, he was appointed director of organisation for the anti-Treaty Republicans, who then took over the Four Courts in April. When the Four Courts garrison surrendered in June, he managed to escape immediately and was promoted to acting assistant chief of staff and officer commanding the Northern and Eastern Divisions, or half of Ireland. In early November he was captured in a dramatic shoot-out and was severely wounded. Ironically, his wounds probably saved his life, as otherwise he would have been court-martialled and executed. While in Mountjoy Gaol in 1923, O’Malley was elected as TD for North Dublin, and later, despite his poor health, he joined the forty-one-day hunger strike. Nevertheless, he survived – a matter of mind over body!

Having been released from prison in July 1924 and still in poor health, O’Malley went to sunny southern Europe to help him recover his health. He returned to his medical studies in 1926, but in 1928 headed for the United States. While there he wrote his much-acclaimed autobiographical memoir, On Another Man’s Wound. It was published in 1936, after he had returned to Dublin in 1935. He had spent seven years writing that book, which he meant to be more of a generic story of the Irish struggle woven around his own activities. The book was a literary success and added to his reputation among his former comrades.

O’Malley’s memoir on the Civil War was not ready for publication, as it required more research, and over the next twenty years he sought to become more familiar with the Civil War period as a whole. What started out in the late 1930s as an effort to supplement his own lack of knowledge, had developed by 1948 into a full-blown enterprise to record the voices, mostly anti-Treaty Republican, of his comrades of the 1916–23 struggle for independence. He interviewed more than 450 survivors, across a broad spectrum of people, covering the Tan War and the Civil War – all this at a time when the government was establishing the Bureau of Military History to record statements made by participants in the fight for freedom.

In the course of his interviews O’Malley collected a vast amount of local lore around Ireland. In 1952 he wrote a series of articles for The Kerryman, but then withdrew them before publication. Instead he used the articles for a series of talks on Radio Éireann in 1953. Subsequently those lectures were published in a series called IRA Raids in The Sunday Press in 1955–56. In the meantime he used the interviews to edit his own Civil War memoir, The Singing Flame, published posthumously in 1978, and to write a biographical memoir of a local Longford Republican organiser, Seán Connolly, entitled Rising Out: Seán Connolly of Longford, 1890–1921, also published posthumously, in 2007.

O’Malley was familiar with interviewing people about folklore and was well read in Irish and international folklore traditions. In the early 1940s he took down over 400 folktales from around his home area in Clew Bay, County Mayo. He also collected ballads and stories about the 1916–23 period. His method for his military interviews was to write rapidly in a first series of notebooks as his informant was speaking and then to rewrite his notes more coherently into a second series of notebooks. Occasionally he would include diagrams of the site of an ambush or an attack on a barracks. Given his overall knowledge of the period, based on his own Tan War activities and his Civil War responsibilities, he usually commanded a high regard from his informants. He felt that his former comrades would talk to him and tell him the truth.

From my examination of his interviews, O’Malley does not appear to have used a consistent technique, but rather he allowed his informant to ramble and cover many topics. In his rewrite of an interview he often labelled paragraphs such as Tan War, Truce, Civil War, Mountjoy Gaol, RIC, IRB, Spies, Split, Dug-outs, Round-ups and the like. The tone is conversational, allowing the narrative to unfold. He wrote down the names of people and places phonetically rather than correctly. The interviews are fresh and frank and many of these men’s stories may never have been told even to their children, as they did not speak openly about those times. Family members have said they could hear the voices of their relatives speaking through the O’Malley interviews, because O’Malley had been able to capture their intonations and phrasing so clearly about matters never discussed in the family before.

This present volume includes five O’Malley interviews, covering the activities of the Mid and East Clare Brigades during the War of Independence, the Truce and the Civil War. All of these Clare men rejected the Treaty and so their interviews reflect strong anti-Treaty opinions. None of these men made statements to the Bureau of Military History.

In transcribing O’Malley’s series of interviews we strove for a balance of authenticity of voice, accuracy of transcription and readability. Some modest changes have been made to help the reader better understand the interview. To enable reference to O’Malley’s original pagination, his pages are referred to in bold brackets, such as [64L], the L or R representing the left or right side of his original page. O’Malley often wrote on the right-hand page of a notebook first and then moved on to the left. Extensive footnotes provide a better understanding of the people, places and incidents involved, and some are repeated in more than one interview to allow each interview to be read separately as a complete story. The original text has been largely revised to include correct spellings of names and places, although some errors in general grammar and punctuation have been reproduced where the sense is clear. O’Malley regularly inserted his own comments in parentheses, and these are reflected for the sake of clarity in this volume in italics following the abbreviation EOM. Some editorial comments or clarifications have been added in square brackets.

Each interview has been reproduced here in full. In some places O’Malley left blank spaces where he was missing information, and these are represented by ellipses. Ellipses have also been used to indicate where the original text is indecipherable. The style of local phrasing used in the interviews has been retained, but some of this is no longer in common usage and may read strangely to the modern reader. In some instances O’Malley included names and facts that do not seem fully relevant, but these have been retained in order to maintain the integrity of the original interview.

We have relied on the integrity of O’Malley’s general knowledge of facts and his ability to question and ascertain the ‘truth’, but clearly the details related here to O’Malley reflect only the perceptions of the individual informant rather than the absolute historical truth, and the reader must appreciate this important subtlety. Also these interviews do not give a complete account of the role played by each individual during this period.

In the case of Clare, O’Malley interviewed his informants only once and so there is little duplication within each interview, but several of the men do speak about the same incidents and naturally there are some differences between their versions. This illustrates clearly how one incident can be viewed differently by different people. O’Malley worked as an organiser in Clare in mid-1919 and again in May 1920 for a short period but was not actually involved in any of the critical Clare actions recorded in these interviews; however, references are made to him by some of the men interviewed.

For those not familiar with the structure of military organisations such as the IRA during this period, it might be helpful to know that the largest unit was a division, which consisted of several brigades, each of which had several battalions, which in turn were composed of several companies at the local level. There were usually staff functions, such as intelligence and quartermaster roles, at division, brigade and battalion levels, and usually only officers at the company level.

Introduction

County Clare played host to some of the most momentous and important political and military events during the Irish revolution of 1913–23. The military campaign waged by the IRA against the British forces in Clare during the War of Independence was one of the most successful conducted nationally, and Republicans from Clare also made major contributions to the Republican struggle in other counties. As well as a strong Republican heritage, stretching back to the United Irishmen in the 1790s and the Fenian Rising of 1867, there was also a very strong radical agrarian movement in Clare that sought to break the power of wealthy landowners and redistribute the land they held to an impoverished local peasantry. Agrarian violence and unrest in Clare were so widespread in the early years of the twentieth century that the British government declared County Clare an ‘Area of Disturbance’ in 1907.1

By that time the secret revolutionary movement called the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) had collapsed or been reduced to ‘a drinking club’ in many parts of Ireland. However, Clare was an exception, and an active and well-organised IRB network existed in various parts of the county long before Seán MacDiarmada and Thomas Clarke began reorganising and reforming the movement throughout Ireland in 1910. In north Clare Thomas O’Loghlen had recruited a group of young IRB members who actively opposed local recruitment by the British Army, engaged in arms training and founded and controlled local branches of both Sinn Féin and the Irish Volunteers. In Meelick, in south-east Clare, Michael Brennan and his brothers were amongst the most active and militant members of the ‘Wolfe Tone Club’, an IRB front organisation based in Limerick city.

During the 1916 Rising it was planned that part of the German arms shipment headed for Kerry would be shipped to Clare to arm these IRB groups. When this plan failed, Republicans in Clare attempted to take independent action to assist their comrades who were fighting the British forces in Dublin and Galway. The IRB in north Clare sabotaged the local communications network, while Michael Brennan made determined but ultimately futile efforts to convince the leadership of the IRB in Limerick city to join the rebellion.

After the collapse of the Rising, Sinn Féin’s victory in the East Clare by-election of July 1917 was of huge importance to the efforts of the Republicans to rally and reorganise their forces. The Sinn Féin candidate, Éamon de Valera, was best known to the local electorate as ‘the fella with the funny name’, and the massive vote that elected him was based not on his personal popularity but on his status as a veteran of the Rising who espoused Republicanism and the use of physical force to achieve Irish independence. The fact that the previous member of parliament for East Clare had been Major William Redmond made the Republican victory all the more poignant. William was a brother of John Redmond, the leader of the ‘constitutional’ nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), and had been killed fighting for the British Army during the First World War, his death triggering the by-election.2 De Valera’s election in East Clare happened shortly after similar electoral victories in North Roscommon and South Longford, and it inspired the slogan ‘The Irish Party – wounded in Roscommon, killed in Longford and buried in Clare’. In the general election held just over a year later, the Republicans won a landslide majority, securing seventy-three of the 105 Irish seats in the British parliament – effectively destroying the IPP in the process.

At the same time, the IRA in Clare began meeting, marching and drilling publicly in open defiance of British law, and this led to the widespread arrests of local Republican leaders across the county. Four leading IRA officers – Patrick, Michael and Austin Brennan from Meelick and Peadar O’Loughlin from Liscannor – refused to recognise the right of a British court to try Irishmen in Ireland and went on hunger strike. The tactics developed by these Claremen were soon adopted nationally and led to a mass hunger strike amongst IRA prisoners in Mountjoy Prison in September 1917. Thirty-eight Republican prisoners took part in the hunger strike, seventeen of whom were Claremen. The hunger strike ended and all of the prisoners were released after their comrade Thomas Ashe died following a botched attempt by the prison doctor to force-feed him. Ashe’s death produced a huge surge in support for the Republicans and over 20,000 people followed his funeral cortège in Dublin. The tactics developed by O’Loughlin and the three Brennan brothers were so effective that they have been utilised ever since, and twenty-two Irish Republicans have died while on hunger strike during the twentieth century.

The very first member of the IRA killed by the British forces during the War of Independence – Robert Byrne, adjutant of the 2nd Battalion of the IRA’s Mid Limerick Brigade – died at Knockalisheen in Meelick, County Clare, on 7 April 1919.3 Byrne was the first of ninety-five fatalities that occurred in Clare during the War of Independence.4 The conflict in the county was so intense it had the fourth highest number of people killed per head of population.5 The IRA were extremely active in Clare throughout the conflict, and Clare’s three IRA brigades inflicted at least forty-one fatalities on the British forces, killing nineteen RIC constables, nine Black and Tans, eleven British soldiers and two members of the Royal Marines.

The people of Clare also suffered some of the worst British reprisals in revenge for these attacks. In April 1920 a British military patrol launched an unprovoked attack on a group of unarmed Sinn Féin supporters in Miltown Malbay, killing three people attending a celebration marking the release of Republican prisoners from Mountjoy Prison. In September 1920 the British forces avenged the deaths of their comrades killed in the Rineen Ambush by running amok in Miltown Malbay, Lahinch and Ennistymon, killing six people and destroying or damaging over seventy houses and business premises. Members of the RIC’s Auxiliary Division killed four local men they were holding prisoner at Killaloe in November 1920 in reprisal for IRA attacks on the RIC. The Republicans also suffered heavy losses in Clare during the War of Independence, with fifteen IRA Volunteers and one Fianna Éireann scout being killed – the majority of them died in British reprisal killings and assassinations.6

In comparison to the War of Independence, there was relatively little activity in Clare during the Civil War, but nonetheless Claremen were active on both sides during that conflict. The very first Republican fatality of the Civil War was a Clareman: IRA Volunteer Joseph Considine from Clooney was shot dead by Free State Army soldiers in Dublin on 28 June 1922, shortly after the ‘Battle of the Four Courts’ began. At least ten IRA Volunteers and three Free State soldiers were killed in Clare during the Civil War, while Commandant Con MacMahon and Volunteer Patrick Hennessy, both natives of Clooney, were executed by a Free State Army firing squad at Limerick Jail on 20 January 1923.

By the spring of 1923 it was clear to the Republicans that the Civil War was all but over and that the Free State had won. Frank Aiken, the IRA chief of staff, ordered all IRA Volunteers to dump their arms and to cease hostilities against the Free State Army from 30 April. The announcement of the ceasefire was not enough to save the life of Patrick O’Mahony, an IRA Volunteer who was executed by the Free State Army at Ennis Jail the morning after it was announced. Nor did the ceasefire save Christopher Quinn and William O’Shaughnessy, the last two Republicans killed in official Free State executions. Quinn and O’Shaughnessy were shot by a firing squad at Ennis on 2 May 1923, two days after the Civil War had ended.

Although there can be little doubt about the significant contribution Clare Republicans made to the Irish revolution, historical memory of the period has tended to overlook the county. For years the history of the Irish revolution was dominated by the published memoirs of a small number of War of Independence veterans, particularly Dan Breen’s My Fight for Irish Freedom and Tom Barry’s Guerilla Days in Ireland. Although these were highly localised accounts of the conflict in Tipperary and Cork respectively, they were written in a very engaging and accessible style and quickly became bestsellers, making their authors household names throughout Ireland. Michael Brennan was the only senior Clare veteran of the War of Independence to publish his memoirs, but his book, The War in Clare, did not appear in print until 1980. Brennan’s book never sold as well as the earlier memoirs and, because he had fought on the pro-Treaty side during the Civil War, he was seen by some to have compromised his principles, making him a much less romantic figure than the likes of Breen and Barry.

In the late 1940s a series of county histories of the War of Independence was published. The first of these was Kerry’s Fighting Story, published in 1947, and this was quickly followed by Rebel Cork’s Fighting Story (1947), Limerick’s Fighting Story (1948) and Dublin’s Fighting Story (1948). Although the military record of the IRA’s three Clare brigades was equally deserving of inclusion in the series, there was no ‘Clare’s Fighting Story’. Instead a handful of articles on IRA operations in Clare was included in With the IRA in the Fight for Freedom (1955), a general history of the War of Independence that included contributions written by IRA veterans from all over Ireland.

Coinciding with the publication of these books, the Irish government established the Bureau of Military History (BMH) in 1947 to record the experiences of those who had taken part in the Rising and the War of Independence. The Bureau recorded 1,773 witness statements from those who had participated in the Irish revolution. After the Bureau had finished its work in 1959, eighty-three steel boxes containing the material it had amassed were sealed and locked away in the strongroom of Leinster House. The Irish government justified the closure of the Bureau’s collection on the basis that its contents were too controversial. One government official commented: ‘If every Sean and Seamus from Ballythis and Ballythat who took major or minor or no part at all in the national movement … has free access to the material, it may result in local civil warfare in every second town and village in the country.’7 The Bureau’s archive remained closed to the public until 2003, when the last surviving veteran who had given testimony died.

The BMH’s collection is now relatively well known to the public because it has been widely used by historians since its release. For example, my first book, Blood on the Banner: the Republican Struggle in Clare, made extensive use of the recently declassified BMH statements to give a blow-by-blow account of the War of Independence in Clare. The fact that most of the Bureau’s collection is now available online for free means that it is often the first stop for historians and members of the public who are researching the period, and it has made a major contribution to our understanding of modern Irish history.

However, an equally important collection of veteran testimony has, until recently, been forgotten, even though it has been available to the public for decades. Ernie O’Malley, who took part in the 1916 Rising and was a senior IRA officer throughout both the War of Independence and Civil War, began interviewing and recording his fellow veterans in the 1930s on a casual basis. By 1948 his interview project had developed into a full-time enterprise, and by 1954 he had interviewed more than 450 veterans of the conflict. Most of O’Malley’s interviewees were former IRA comrades, but he also interviewed a number of British soldiers and veterans of the Free State Army.

As well as first-hand accounts of the Rising and War of Independence, O’Malley’s interviews contain a wealth of information about the Civil War – a conflict that those speaking to the BMH were officially prohibited from discussing. Moreover, quite a number of those who agreed to be interviewed by O’Malley did not give testimony to the BMH. This was largely due to the bitter legacy and divisions left by the Civil War. Irish Army officers, who were mostly veterans of the Free State Army, conducted the Bureau’s interviews, and many of the veterans who had fought on the Republican side during the Civil War refused to co-operate with them. When one Republican veteran of the Civil War was approached by the Bureau to make a statement about his experiences during the War of Independence, he refused, but suggested that some of his former comrades could have given the Bureau a lot of information – if the Free State Army hadn’t killed them!8 However, many of the men who declared that they would rather burn their memoirs than share them with the ‘Free Staters’ in the BMH were willing to talk to O’Malley.

This book contains interviews with all five of the Claremen who were interviewed by O’Malley. None of these men gave statements to the BMH. They contain valuable testimony about the War of Independence and Civil War in Clare, which was not recorded elsewhere and would have been irretrievably lost were it not for O’Malley’s hard work and dedication. The first four of the interviews in this book are with veterans of the IRA’s Mid Clare Brigade. Séamus Hennessy and John ‘Seán’ Burke had both taken part in the Rineen Ambush, and their interviews contain important accounts of the attack which was, at that time, the largest and most successful operation that the IRA had conducted against the RIC. Michael MacMahon’s interview includes an eyewitness account of the reprisals in Miltown Malbay carried out by the British forces in revenge for the ambush. Paddy Con MacMahon’s interview gives a fascinating account of IRA operations in Ennis during the War of Independence, including details of Republican sympathisers within the RIC garrison in Ennis who provided the local IRA with information, and the activities of members of the local loyalist population who assisted the British forces. The Civil War also features prominently in Paddy ‘Con’ MacMahon’s interview and he discusses his capture during the ‘Battle of the Four Courts’ in Dublin and his lengthy internment in Mountjoy Prison, where he shared a cell with the IRA leader Liam Mellows.

O’Malley also interviewed Paddy McDonnell, who was a leading member of the IRA’s East Clare Brigade. McDonnell was friendly with Alfie Rodgers and Michael ‘Brud’ McMahon, two of the ‘Scariff Martyrs’, who were killed by members of the RIC Auxiliary Division on Killaloe Bridge. In his interview McDonnell describes meeting Rodgers and McMahon just a few hours before they were captured and killed, and giving them a poignant order to take more care because they were at risk of capture.

O’Malley made a hugely important, if grossly under-appreciated, contribution to the study of modern Irish history. There is no doubt that if his interviews had been typed and were easily legible, their significance would have been recognised years ago. However, before O’Malley became a revolutionary he was a medical student at UCD and one of the first things he seems to have been taught there was how to write like a doctor! Because of the appalling state of his handwriting O’Malley’s interviews have too often been dismissed as being indecipherable or worthless, despite the important material they contain. For example, one of O’Malley’s interviewees revealed that future taoiseach Seán Lemass was one of the IRA Volunteers involved in the assassination of British intelligence officers on ‘Bloody Sunday’. Normally the value of such information would be recognised by historians, but one academic who found that this information conflicted with his theories about Lemass’ IRA activities simply dismissed the information by denouncing the O’Malley interviews as ‘a series of illegible notes scribbled by Ernie O’Malley later in life’.9

As well as the possibility that the O’Malley interviews will continue to be dismissed or ignored if they are not transcribed and published, there is also the danger that their contents might be misinterpreted by those who cannot understand O’Malley’s handwriting. This raises the possibility that misleading quotes purporting to come from his interviews might be used to support questionable interpretations of Irish history. In The Year of Disappearances Gerard Murphy made the claim that the IRA executed three anonymous Protestant teenagers in Cork city and secretly buried their bodies, sparking an IRA campaign of sectarian murder ‘that led to dozens of deaths’ and ‘the flight of hundreds of Protestant families’.10 There is no verifiable evidence that these anonymous victims ever existed, much less that they were killed by the IRA, a fact Murphy attributed to ‘a spectacular cover-up’ and ‘a big conspiracy’ involving the press, the British government and even Cork Protestants themselves.11 The main piece of verifiable ‘evidence’ Murphy had for his claim was a misreading of an interview in the O’Malley notebooks.12 Murphy’s inaccurate and misleading quote was so central to his thesis that he referred to it fifteen times in his book and used it as a title for one of his chapter headings. Had Murphy been able to read the O’Malley interviews correctly, or had his transcriptions been checked for accuracy, he would have realised that the O’Malley interview he cited made no mention of the killing of three Protestant teenagers by the IRA and that there is no verifiable evidence in the historical record to indicate that the alleged event ever happened.13

Consequently an important disclaimer must be added to this transcription: whilst every effort has been made to accurately decipher and transcribe O’Malley’s difficult handwriting, mistakes and errors are of course still possible, and any reader relying on a specific sentence or passage in this book to support an important argument should visit the UCD Archives to check the original document and confirm the exact transcription for themselves. In some places it has been necessary to insert additional words, indicated by square brackets, or some punctuation into the text to make grammatical sense of a passage. In other instances where it has not been possible to read a particular word or phrase written by O’Malley, a suggested transcription indicated by a question mark has been inserted. All ampersands have been written as ‘and’.

Finally, in addition to the five interviews with IRA veterans from Clare conducted by O’Malley, this book also contains extracts from a memoir written by Liam Haugh, which O’Malley had written into his notebooks.14 Haugh was vice-commandant of the IRA’s West Clare Brigade during the War of Independence and in 1935 he wrote an account of his experiences during the war. He did not publish the memoir but donated a copy of it to the BMH. Although the Bureau’s collection was officially classified, O’Malley managed to get unofficial access to it through Florence ‘Florrie’ O’Donoghue, a veteran of the War of Independence in Cork who was friendly with O’Malley and who had been instrumental in convincing President Éamon de Valera to establish the Bureau. O’Malley recorded an abridged version of Haugh’s memoir in his notebooks alongside the record he made of his interviewees’ testimony.

Although the extracts from Haugh’s memoir copied by O’Malley are not the record of an interview, they have been included in this book as Appendix 1 because they are nonetheless a valuable first-hand account of the period. O’Malley, recognising this, used the memoir as a source for an article he wrote on events in west Clare, which was published in TheSunday Press in 1955. O’Malley’s article caused significant controversy as it mentioned the killing of Patrick D’Arcy, an IRA Volunteer who was executed as a suspected spy in 1921. D’Arcy’s shooting is also mentioned in John ‘Seán’ Burke’s interview, but because the incident is too complex and controversial to be dealt with in a footnote, I have explained the full story as far as it is known in Appendix 2.

Several of O’Malley’s interviewees also mention the shooting of Alan Lendrum, a former captain in the British Army who had been appointed resident magistrate in Kilkee. The circumstances of Lendrum’s death have been grossly distorted over the years for propaganda purposes, so Appendix 3 has been added to give a brief factual account of his shooting.

Now that the BMH interviews have been declassified and the Military Service Pensions records relating to the same period are also being released and made available online, Ernie O’Malley’s notebooks are probably the last significant body of veteran testimony relating to the Irish revolution of 1916–23 not easily accessible to the public.15 Thankfully a number of historians are already hard at work transcribing the notebooks on a county-by-county basis for publication. This book is my small contribution to that effort.

Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc

Mid Clare

Michael MacMahon

(UCDA P17b/130, pp. 64-66)

Michael Joseph MacMahon, better known as Micko and Mike-O, was born on 29 June 1902. He was the only child of Thomas MacMahon and Jane MacMahon (née Mahony) who lived at Clonbony, Miltown Malbay, County Clare. His father, Thomas, was a railway worker employed on the West Clare Railway.

Michael was a talented athlete who excelled at cycling and he won a number of track and sports day events. His athletic skills were put to good use after he joined the IRA and he often acted as a cycle courier carrying IRA dispatches.

Michael married Helena Mason from Scariff in 1935 and they had five sons: Michael-Vincent, Tom, Fintan, John and Tony (Anthony). He worked for Coras Iompair Éireann (CIÉ) as a clerk and was initially posted to Longford, but was later transferred to Castlebar in Mayo. In 1949 he was appointed stationmaster of Westport Railway Station. He retired in 1967.

Michael continued to have a keen interest in cycling and followed both domestic competitions, such as the Rás Tailteann, and international events, including the Tour de France. He spent much of his retirement playing golf, and both he and his wife served as captains of Westport Golf Club. Apart from following the political fortunes of his friend Patrick J. Hillery, who became president of Ireland, Michael was not active in party politics. He died in February 1985, aged eighty-three.

***

[64L] Ignatius O’Neill’s1 family in Miltown Malbay had a big shop, a hardware and builders’ providers.2 Ignatius was wild and he joined the British Army and served in the Irish Guards.3 He was in the United States also, but he didn’t stay there too long. There was an RIC Barracks in Miltown Malbay which contained Tans and RIC, between 30 to 35 in it.4 It is a dance hall now, and there are houses at either side of it. The [British] military commandeered the Town Hall. They came into the place early in 1920, or in 1919. They were the Highland Light Infantry and they were toughs, and the K.O.S.B., the King’s Own Scottish Borderers; and a tough crowd they were.5 There was an English regiment, all of them conscripts, there for a while: the Sherwood Foresters.6 We had frequent visits from the Auxiliaries.7 They crossed from Kerry in boats. They came on horses, in lorries, and on foot. I was rounded up in 1921 and I was forced to fill in trenches which had been opened up by the IRA.8 They put us into Crossley Tenders and they brought us to between Miltown Malbay and Kilrush [in] 8 or 9 Tenders.9 I heard the lorries and I disappeared. I live about 150 yards outside of the town, and a lad made for my house to escape. He was followed and I was wounded.

When we were filling in the trenches by means of stones from the walls on the edges of the roads, they ordered us to carry big stones and I said that I couldn’t. I got a blow of a rifle and I was told that the next time I said that it would be the last time for me.

[The Rineen Ambush:]10 A letter which was in the post must have gone to the [British Army] officer who was in charge of the old Workhouse in Ennistymon.11 When he received it the lorry had left on its way to Miltown Malbay. Then there was probably a delay in the setting out of the military to collect their forces [64R] first and it took time. (EOM: This letter sent a warning to the officer to say that there would be an ambush that morning on the road to Miltown Malbay.) At 1.10 p.m. we heard the firing [the] very day this lorry went to the west and then they remained for about three-quarters of an hour and then they returned again.12 Probably this unit that went out was a patrol with a Tan driver in civvies, or maybe he wasn’t. These two [of the constables] ran out towards the sea at the first volley and they were both killed. In all 8 others were killed; a driver and 7 of the RIC.13

The RIC, on the other hand, did not know a thing about the ambush. I could see the figures on top of the hill for it is about a mile away.14