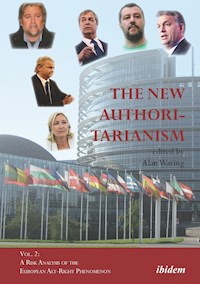

The New Authoritarianism. Vol. 2 E-Book

30,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ibidem

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This two-volume book considers from a risk perspective the current phenomenon of the new Alt-Right authoritarianism and whether it represents ‘real’ democracy or an unacceptable hegemony potentially resulting in elected dictatorships and abuses as well as dysfunctional government. Contributing authors represent an eclectic range of disciplines, including cognitive, organizational and political psychology, sociology, history, political science, international relations, linguistics and discourse analysis, and risk analysis. The Alt-Right threats and risk exposures, whether to democracy, human rights, law and order, social welfare, racial harmony, the economy, national security, the environment, and international relations, are identified and analysed across a number of selected countries. While Vol. 1 (ISBN 978-3-8382-1153-4) focusses on the US, Vol. 2 illuminates the phenomenon in the United Kingdom, Austria, France, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Italy, Hungary, and Russia. Potential strategies to limit the Alt-Right threat are proposed.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 690

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

ibidemPress, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

Dedication

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Introduction: Risk and the Alt-Right

The Book’s Target Readership

The Book’s Rationale

The Editor’s Perspective

Risk and the Alt-Right Context

The Book’s Style, Content, Authors and Structure

References

Part 1: The Nature of the Alt-Right Ideology

Chapter 1: Defining the Evolving Alt-Right Phenomenon

Abstract

The Conservative Tradition

The Alternative Right

The Alt-Right Emergence in the United States

The Alt-Right Emergence in the UK

The Trans-National Appeal of the Alt-Right

Defining the Alt-Right

References

Appendix 1.1 Alt-Right Representative Groups and Parties

Chapter 2: Psychological Aspects of the Alt-Right Phenomenon

Abstract

Making Psychological Sense of the Alt-Right

Psychological Factors and Political Preferences

The Psychology of Fear and Risk

Fear of Foreigners and Immigrants

Fear of Globalisation and Job Losses

Fear of Experts

The Political Psychology of Anger

Personality, Values and the Alt-Right

Other Psychological Factors Evident in the Alt-Right Phenomenon

The Issue of Alleged Personality Disorders

Conclusion

References

Part 2: The Alt-Right in Selected European Countries

Chapter 3: Brexit and the Alt-Right Agenda in the UK

Abstract

The Brexit Project

Britain’s EU Membership

The Origins of a Eurosceptic Agenda and Brexit Movement

Immigration and its Perceived Second–Order Effects

EU Bailouts of Ailing Member States

Institutional Incompetence, Fraud and Corruption

Perceived Unaccountable Overbearing Inertia

Failure of EU Subsidiarity Principle

Perception of EU Refusal to Reform

Manipulation of Brexit by UKIP and the Far-Right

Conclusion

Risks from the Alt-Right’s Stance on Brexit

Brexit-related Risks for the UK Alt-Right

References

Chapter 4: The Politics of Cultural Despair: Britain’s Extreme-Right

Abstract

The Politics of Cultural Despair

The ‘Sacred Flame’: the Ideological Ancestors of Today’s Extreme Right

“A desperate situation”: the British Union of Fascists

“In the Grip of Degenerative Forces”: the National Socialist Movement and the National Front

“The Art of the Possible”: the British National Party

“No Surrender to the Taliban”: the English Defence League

“We Want Our Country Back”: Britain First

“Death to Traitors”: National Action

Europe, Youth, Reconquista!: Generation Identity

Conclusions

References

Further Reading

Chapter 5: The Murder of Jo Cox MP: a Case Study in Lone Actor Terrorism

Abstract

Jo Cox’s Murder

Lone Actor Terrorism and the Extreme-Right

Long- and Short-term Factors Explaining Mair’s Radicalisation

Mair’s Relationship with a Wider Milieu

Conclusion

References

Chapter 6: The Austrian Freedom Party

Abstract

Right-Wing Ethno-Nationalism

The Extreme-Right in Austria Since 1945: Tracing the History of the FPÖ

The Contemporary Extreme-Right in Austria

Recontextualising Extreme-Right Ideology: from Closed-Door Meetings to Handbooks

The Extreme-Right in Election Campaigns

Conclusion

Risks for Austrian Society and Governance

Risks for Individuals

Risks for the FPÖ

References

Chapter 7: The Far-Right Alternative für Deutschland in Germany: Towards a ‘Happy Ending’?

Abstract

German Far-Right Attitudes in Populist Form

Setting the Stage: the German Far-Right from 1945 to the AfD

Saving ‘the People’: the AfD from 2013 to 2018

The Beginning: Greek Debt and the EURO

The Middle: Rescuing ‘the German People’

The (Preliminary) Ending: Election Campaign, Triumph and Beyond

Narrating Risk—Narrative Modes

Conclusion

References

Chapter 8: Marine Le Pen and the Front National in France: Between Populisms in the 2017 Elections and Beyond

Abstract

Marine Le Pen and the FN

Beyond a Conjunctural Account

Nativist Authoritarianism

Statist Sovereignism

Diverging Electorates

Beyond 2017

Conclusion

Risks for the Front National

Risks for Marine Le Pen

Risks for French Society, Governance, and Democracy

References

Chapter 9: Wilders’ Party for Freedom and the Dutch Alt-Right

Abstract

PVV History

Who Votes for the PVV and Why?

Historical Legacy

PVV Ideology

Anti-Constitutional Election Programme

Mainstreaming: Election Programmes of Political Parties

The CDA, VVD, and Other Parties

Christian SGP

Anti-Muslim Actions Prior to 2017 Election Campaigns

The Liberal Party VVD

The Poldering Principle

The Dutch Alt-Right Movement

Erkenbrand

Forum for Democracy

Altrechts.com

Conclusion

References

Chapter 10: A Case Study of Anders Behring Breivik, Extreme-Right Terrorist

Abstract

Breivik, the Extreme-Right Anti-Hero

Breivik’s Massacre

Breivik’s Ideology

The Role of the Internet

Violent Proclivities of Neo-Breivik Acolytes

Breivik’s Mental State

Conclusion

References

Chapter 11: The Alt-Right Ideology in Russia

Abstract

The Alt-Right, Russian Style

Mainstream Alt-Right: Vladimir Putin

Geopolitical Alt-Right: Alexander Dugin

Ultranationalist Alt-Right: Liberal Democratic Party of Russia

Chauvinist Alt-Right: Pamyat and Russian National Unity

Conclusions

References

Part 3: Conclusion

Chapter 12: A Risk Analysis and Assessment of the European Alt-Right and its Effects

Abstract

A Collated Risk Analysis and Assessment

Risk as a Cognitive Phenomenon: Objective and Subjective Risk

Pure Risk and Speculative/Opportunity Risk

Risk Analysis and Assessment Methodology

Findings and Conclusion

Appendix 12.1: Factors Affecting Risk Perception and Therefore Risk Analysis

Failures of Hindsight, Foresight and Learning

Ignorance and Bounded Rationality

Groupthink, Authority and Conformity

Risk Perception and Risk Attitudes

Risk Appetite

Risk Tolerability

Motivation and Expectancy

Risk Decision-Making

Cultural Effects

Socially Constructed Emergence

Appendix 12.2: Qualitative Risk Analysis of the Alt-Right Phenomenon

The Alt-Right in Selected European Countries

Appendix 12.3: Risk Assessment Summary Tables

Appendix 12.4: Rating and Scoring Heuristics Used in this Chapter

References

Chapter 13: A Prognosis for the New Authoritarianism

Abstract

A Potential Alt-Right Future

Relative Strengths of the Alt-Right

Relative Weaknesses of the Alt-Right

Opportunities for the Alt-Right

Threats to the Alt-Right

Alt-Right Evolution

Projected Scenarios for Alt-Right Evolution

Conclusion

References

Chapter 14: Potential Strategies to Limit the Alt-Right Threat

Abstract

Addressing an Existential Threat

Legislative, Law Enforcement, and Judicial Strategies to Combat the Alt-Right Threat

Internet, Social Media, and Related Strategies

Educational Strategies to Combat the Alt-Right Threat

Political and Economic Strategies to Combat the Alt-Right Threat

Tackling the Alt-Right Overall

Tackling the US Alt-Right

Grassroots and Mass Action Strategies

Conclusion

References

Glossary

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

About the Editor and Authors of Vol 1 and Vol 2

Editor and Primary Author:

Contributing Authors:

Copyright

Dedication

This two-volume book is dedicated in memoriam to the Lord Peter Temple-Morris QC, who inspired and encouraged the editor to embark on the project. Originally scheduled to contribute the Foreword, throughout 2017 and into 2018 he battled with much fortitude against increasingly severe illness and operations and became too frail to write. Sadly, he died aged 80 on May 1, 2018.

Lord Temple-Morris’s British parliamentary career as an MP ran from 1974 to 2001, for the most part as a Conservative of the liberal ‘One Nation Tories’ group, before crossing the floor of the House to Labour in 1997. He entered the parliamentary upper chamber (House of Lords) in 2001. His strong distaste for authoritarianism (which he saw as increasingly prevalent in the Conservative Party), and an equally strong belief in justice and moderation, characterised his world-view. Serving variously on the Justice and Foreign Affairs Select Committees and others, he was also a key member of the British-Iranian All-Party Parliamentary Group from 1989 to 2005, and in 1990 launched the British-Irish All-Party Parliamentary Group. He is credited with a substantial contribution to the Northern Ireland peace process that culminated in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

This book is a fitting tribute to his sense of justice and moderation and ‘jaw-jaw’ approach to difficult political issues, especially in foreign policy areas.

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

ADL Anti-Defamation League (US)

AfD Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany, political party)

AKEL Progressive Party for the Working People (communist party in Cyprus)

BCE Before Current Era

BNP British National Party

BP British Petroleum

CIA Central Intelligence Agency

CPS Crown Prosecution Service (UK)

CVE Countering Violent Extremism

EC European Commission

ECB European Central Bank

ECHR European Court of Human Rights

ECJ European Court of Justice

EDL English Defence League

EEC European Economic Community

EHS Environment, Health, and Safety

EP European Parliament

EU European Union

FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation

FN Front National (France)

FPÖ Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (Austrian Freedom Party)

FvD Forum for Democracy (Netherlands)

GDP Gross Domestic Product

IMF International Monetary Fund

IRGC Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (Iran)

IS Islamic State

ISIS Islamic State in Iraq and Syria

KKK Ku Klux Klan (US)

LDPR Liberal Democratic Party of Russia

LGBT Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual

MEP Member of European Parliament

MMR Measles, Mumps, and Rubella

MP Member of Parliament

NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization

Neo-con Neo-conservative (US)

NHS National Health Service

NIHCE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK)

NPL National Policy Institute (US)

Obamacare Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010 (US)

ONS Office for National Statistics (UK)

ÖVP Österreichs Volkspartei (Austrian People’s Party)

PCA Paris Climate Accord

PEGIDA Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes (far-right German movement)

PRC People’s Republic of China

PVV Partij Voor Vrijheid (Party for Freedom in Netherlands)

QRA Quantified Risk Assessment

RNU Russian National Unity party

RWA Right Wing Authoritarianism

SDO Social Dominance Orientation

SPÖ Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (Austrian Social-Democratic Party)

TPP Trans Pacific Partnership

UHC Universal Health Care

UK United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Northern Ireland)

UKIP United Kingdom Independence Party

UN United Nations

UNCAC United Nations Convention Against Corruption

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

US United States (of America)

VVD Dutch Liberal Party

WWI World War One

WWII World War Two

Foreword

This edited two-volume collection of papers comes at a crucial time for Europe, the United States, and the wider world. Momentous economic and political changes of the last few years continue to have impacts. Waring, a prominent author in risk, its assessment and management, provides the reader with a refreshingly different analytical focus for the phenomenon of resurgent authoritarianism now evident in populist and radical right-wing politics. The subject matter is controversial, and the temptation to descend into polemic is resisted by the weight of scholarly analysis from such a range of distinguished international authors. My close personal and professional relationship with Alan may have affected my view of this book, but it has been a long time since I felt that I craved to read a book chapter after chapter! The Alt-Right’s vivid relationship, with both current events and perseverant effects, makes it a living book. I feel honoured to have had the opportunity to be one of its first readers.

The New Authoritarianism’s eminently qualified contributors bring to the task an eclectic range of specialisms and expertise on the subject matter. The book also comes with some unique features. It is the first book on the Alternative Right to explicitly frame the narrative around a risk analysis. The expected political analysis, which so often on its own can seem rather sterile, is encompassed within a much broader structured analysis focused on risks for various parties—society, governments, sectors, individual citizens, and the Alt-Right themselves. In addition, there is a special early chapter examining the psychological aspects of the Alt-Right phenomenon, which include the promulgation of fear as a political tactic, the psychological characteristics of nationalist and supremacist ideology, as well as how best to consider allegations of mental instability and personality disorder against particular politicians.

The book’s working definition of the Alt-Right is twofold: (1) as an ideology, the spectrum of right-wing world-views outside traditional conservatism, which begins with a dissatisfaction with the mainstream political process and character and frustration by perceived impotence of traditional conservatism, and runs through populist, hard-right, ultra-right, and extreme-right ideology; (2) as an identifiable group, those having such world-views.

The New Authoritarianism book seeks to explain the Alt-Right phenomenon on a global level as well as nationally. Chapters show that the Alt-Right ideology is shared transnationally—with prominent examples not just in the US but also in all western democracies, as well as Russia and other nationalist authoritarian regimes. Evidence of considerable transnational collaboration between Alt-Right groups in different countries is discussed. The range of chapters in this Volume covers Britain, France, Germany, Austria, Netherlands, Norway, and Russia—and far-right activities in Hungary and Italy are also addressed. Two case study chapters address lone actor far-right terrorism (the murder of Jo Cox MP in Britain, and the bombing atrocity and subsequent massacre in Norway by Anders Breivik), and other chapters address more recent extremist atrocities.

The chapter on Brexit analyses the fragile, problematic relationship of the European Union with the UK and reveals how Alt-Right activists (both populist and far-right) sought to exploit widespread genuine concerns among British voters about some aspects of EU membership and persuade such voters in the Brexit referendum that their only salvation from their fears would be to vote for Brexit. The book argues that, for the Alt-Right, a Brexit result was merely a stepping stone towards their desire for permanent, nationalist right-wing authoritarianism in Britain and an end to the multi-culturalism and cosmopolitanism encouraged by the EU.

The book’s message is that the over-riding thrust of the Alt-Right in western democracies is to achieve a permanent Alt-Right stamp on the governance of each country. They seek to achieve this by persuading, subverting, and as necessary bullying, mainstream and populist conservatism to shift its center of political gravity firmly towards the far-right. The objective of fascist movements in the 1930s to overthrow the state and replace it with a totalitarian regime has been modified to one where the Alt-Right today are largely content (at least in the short-term) to exert a modifying and attenuating influence on electable mainstream conservative governments i.e. to get the latter to ‘correct’ themselves and become more nationalist and authoritarian e.g. democratically elected regimes in Austria, Hungary, Germany.

The book argues that to achieve this the Alt-Right seek the normalization and public acceptability of their nationalist and white supremacist ideology, and so Alt-Right leaders and opinion formers are typically keen to portray their ideology and policies as a reasonable, fair, just, and necessary response to what they assert are dangerous liberal ideas and weak mainstream governance. The Alt-Right portray themselves as society’s saviours, as the only protection against being overwhelmed and destroyed by foreigners, immigrants and their alien ideas, creeds, and cultures.

The book asserts with evidence that, in the Alt-Right coda, any and all means are permissible in pursuit of their ends e.g. deliberate dissemination of lies, fake news, and invented ‘alternative facts’; seeking to replace representative democracy by direct democracy. Both flagrant and subtle defamation in the form of fake global conspiracy propaganda against Jews and Muslims is commonplace, especially using the Internet and social media, the subversion of which the book examines critically in detail. For the far- and extreme-right elements, intimidation, hate crimes, and violence are also acceptable tactics, and the book examines numerous examples.

At the conclusion of each of nine chapters in Part 2, in which specific examples of the Alt-Right phenomenon are addressed, a summary list of risks is included. Towards the end of the book, these risks are collated and individually analysed heuristically for impact, probability and risk rating in a special chapter, making this a unique contribution to an examination of the Alt-Right. As the author emphasizes, this is neither a definitive risk analysis nor the pronouncements of a ‘Risk Oracle’ and the assessment is open to debate. This chapter, in effect, becomes a reference utility and one that is available for application, debate, and further development by anyone who wishes to use it.

The penultimate chapter examines the overall strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats in relation to the Alt-Right, and posits five different potential scenarios for the Alt-Right’s future. While one scenario suggests that the current democratic status quo could be retained, the other four are increasingly authoritarian of which the final two involve Alt-Right coups d’état. A prognosis is made for which of the scenarios are more likely to occur in which countries.

The book’s final chapter includes detailed discussion of a range of strategies for combatting what the chapter’s authors conclude is an Alt-Right threat to democracy. These include legislation and judicial strategies; Internet and social media; education; political and economic strategies; and grassroots and mass action. The book ends on a call for ‘muscular moderation’ to combat the Alt-Right threat, a difficult but nonetheless compelling challenge.

George Boustras

Professor in Risk Assessment

Director of the Center of Risk and Decision Science (CERIDES)

European University Cyprus

Editor-in-Chief, Safety Science (Elsevier)

Acknowledgements

In addition to the authors themselves, the editor would like to thank the following for their support and various contributions to this book.

For contributing the Foreword, advising on, and reviewing the book’s development:

Professor George Boustras, Professor in Risk Assessment and Director of the Center for Risk and Decision Science (CERIDES), European University Cyprus.

For encouraging the creation of this book from its earliest inception:

Emeritus Professor Matthew Feldman, Director of the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR); formerly Emeritus Professor at the Centre for Fascist, Anti-Fascist and Post-Fascist Studies at Teesside University, UK.

The Lord Peter Temple-Morris QC (see Dedication).

Paul Sheils, formerly managing partner of a leading law firm, London.

For advising on the book’s development and reviewing drafts of various chapters:

Professor Ali Ansari, Professor of Modern History and Founding Director of the Institute for Iranian Studies, St Andrews University, Scotland.

Associate Professor Dr Ian Glendon, School of Applied Psychology, Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, Queensland, Australia.

Dr Clodagh Harrington, Senior Lecturer, De Monfort University, member of the Political Studies Association’s American Politics Group and the Trump Project research group.

Dr Roger Paxton, contributing author, reviewer and tireless mentor to the editor throughout.

Long-standing friends and political observers: Liz Buck, avid reader of books; Lynne Jalalian, public and environmental health lecturer; Gavin Jones, author, columnist and social commentator; Susan-Marie Kelly, retired editor and American citizen.

Dr Anton Shekhovstov, Valerie Lange and colleagues at ibidem Verlag for their support, guidance, professionalism, and efficiency throughout the lengthy publishing process.

Last, but by no means least, my wife Mehri, who put up with numerous periods of my detachment from family life during the creation of this book.

Introduction: Risk and the Alt-Right

By Alan Waring

The Book’s Target Readership

Readers of this book are likely to fall into a broad spectrum of professional groups that have, in some way or other, a need to unravel and consider the impact of resurgent nationalism and ultra-conservative agendas on risk issues affecting governments, institutions, corporations, the judiciary, businesses, the media, individual citizens and others, as well as protective strategies against such threats. In addition to a wide range of scholars and academics, such readers will include risk analysts and risk managers of various kinds, politicians and political analysts, intelligence officers, corporate security specialists, corporate ethics and integrity managers, economists, investment analysts, lawyers, journalists, psychologists, sociologists, and civil society leaders and professionals.

Students on a range of Masters and other post-graduate courses are also likely to find the book of value, in such subjects as business administration, risk management, security and counter-terrorism, corporate ethics, government administration, political science, and international relations.

The Book’s Rationale

This book considers, from a risk perspective, the current phenomenon of the new Alt-Right authoritarianism that began to emerge in the first decade of the 21st century, and whether it represents ‘real’ democracy or an unacceptable hegemony potentially resulting in elected dictatorships and abuses. Potential threats and risk exposures, whether to democracy, human rights, law and order, social welfare, racial harmony, the economy, national security, the environment, or international relations, are identified and analysed. Potential strategies to limit threats that might arise from Alt-Right ideology and activities are proposed. The book acknowledges the particular relevance of and contribution to its analysis by such authors as Lyons (2017a and b), Michael (e.g. 2003, 2016, 2017), and Neiwert (2017) on the American right-wing and the emergent Alt-Right phenomenon, and, on the right-wing in Europe, Eatwell and Goodwin (2010), Feldman and Pollard (2016), Goodwin (2011), and Wodak (2015 and passim).

It is axiomatic to state that life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness are fundamental to a democratic society. The American constitution cites these fundamentals explicitly, but they are implicit to all democratic societies. Democratic freedoms naturally threaten the very existence of dictatorships, totalitarian states and pseudo-democracies, as well as putative states run by terrorists such as Da-esh/IS (Islamic State). None of these can exist unless they impose abusive and degrading conditions on their populations, so as to cow them into submission. Although the existence of coercive and often barbaric regimes may seem self-evident, and there are plenty of examples, perhaps a less obvious threat comes from internal extremists within democratic societies who seek radical change by undermining or destroying basic freedoms. While these obviously include IS followers, others just as insidious and dangerous are lurking among us. Ironically, some of the worst internal extremists are those who justify themselves and their often draconian and abusive acts by claiming to offer the public true democracy, true freedom, true security, and true protection against alleged threats. The label Alternative Right or Alt-Right has arisen in recent years to encompass not only the spectrum of beliefs, values, attitudes, opinions, and positions within the Alt-Right world-view, a view more strident, authoritarian, and harsher than conventional conservatism and now regarded by many as extremist, but also the exponents of Alt-Right ideology.

The new Alt-Right authoritarianism that is sweeping the western world could easily be described as neo- or proto-fascist in general character. Traditionally, the fascism label has been applied almost exclusively to right-wing authoritarianism, such as Hitler and Nazism, the Pinochet regime in Chile, the Orban regime in Hungary, and by some even to the Trump administration in the US. However, by virtue of some of its tactics, it could apply equally to left-wing extremism, such as the Chavez and Maduro regimes in Venezuela and the totalitarian regime in North Korea. As a further example, the widely reported bullying and anti-Semitism by authoritarians now controlling the hard-left Momentum faction within the British Labour Party has all the tactical hallmarks of fascism (see e.g. Fisher 2018; Maguire and Fisher 2018; Zeffman 2018). Although this book focusses very much on the Alt-Right (because of its current rapidly growing presence across the west), one should nevertheless also be alert to neo-Marxist extremism wherever it flourishes, to right-wing authoritarian regimes in the non-western world, as well as to IS extremism.

The so-called Brexit Referendum in June 2016, whereby the UK electorate voted by a small margin in favour of leaving the European Union, was a prominent example of the Alt-Right ideology and agenda at work. The pro-Brexit campaign was infused with Alt-Right ideas, language and propaganda. Indeed, there was acknowledged close collaboration between the UK Independence Party (UKIP), the populist prime mover for Brexit, and leading figures and organizations within the Alt-Right movement in the US. Fear of immigrants and concern about allegedly weak immigration controls became the main driving force of the pro-Brexit campaign, along with slogans about allegedly incompetent and overbearing interference in British life by an unelected elite of EU leaders and officials in Brussels. An authoritarian tableau broadly similar to pro-Brexit played out in the Trump campaign in the 2016 US presidential election (see Vol 1). The common theme of Brexit and Trump supporters was that ‘the Establishment’, i.e. government and the traditional political parties, were not listening to them about their concerns on such things as immigration, national control, job losses from cheap imports or jobs moving abroad. Some of these complaints may well be valid up to a point. However, as the respected Times columnist and former British Conservative MP Matthew Parris wrote in January 2017, many of their complaints do not bear much scrutiny in factual terms. He later described the anti-foreigner jingoistic attitudes of the populist Alt-Right in Britain (or ‘the shadow’, as he called them) as “something brutish, something authoritarian, something mean” (Parris 2018). False beliefs and exaggerated fears among an electorate about immigrants, for example, are easy for skilled demagogues to whip up into nationalistic frenzy whereby voters become convinced that their only salvation is to vote for the authoritarian candidate who will ‘protect’ them. However, whatever the merits of their grievances, they have absolutely no right to demand pathological solutions and political leaders have absolutely no right to offer them much less deliver them.

It is often said that truth is the first casualty of war. That could equally apply to politics. It is generally accepted that politicians and their acolytes are likely to cherry pick ‘the truth’ and massage it and finesse it to their best advantage. Presenting their best case is, perhaps, the acceptable face of politicians. The public tolerates it. However, what has been emerging in recent years, and very much so in the US Presidential Election campaign of 2016, is the ‘post-truth’ phenomenon, an altogether different proposition. Post-truth refers to the deliberate fabrication and dissemination of plausible but false news stories, or stories comprising a mixture of fact and damaging fiction, in order to assist in a black propaganda campaign against a political target. Fake news became a weapon-of-choice of the Alt-Right movement in support of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, perhaps unsurprisingly in view of the fact that one of his campaign directors was Steve Bannon, the doyen of Alt-Right propaganda and former editor of Breitbart News, the leading Alt-Right promotional medium. Potentially damaging fake news stories were disseminated about Trump’s electoral rival Hillary Clinton. See, for example, Neiwert (2017).

Since President Trump’s inauguration, however, it became evident that the post-truth fake news tactic had become an integral part of his Presidential policy, whether from his own mouth, his Twitter account, or a variety of official spokespersons. The world was expected to swallow unabashed such demonstrable falsehoods as: a non-existent terrorist massacre at Bowling Green, Kentucky, the number of people celebrating Trump’s inauguration near the Lincoln Memorial far exceeding those at President Obama’s 2009 inauguration, and an accusation that the media barely covered terrorist attacks in Nice, Paris, Berlin and some 75 other locations. Furthermore, when challenged, the lies were either denied, or brazenly repeated, or dismissed as trivial errors. It is instructive that Steve Bannon was appointed by President Trump as his Chief Strategist in his inaugural cabinet, along with other senior Alt-Right representatives. The implications of the widespread use of fake news and fake facts by the Alt-Right political machine are addressed in more detail in chapter 11 of Vol 1.

A common agenda of the Alt-Right movements across the west is to stop immigration. Some, and especially the more extreme elements, also wish to go further and enforce the repatriation or expulsion of all non-whites and non-Christians, particularly Muslims. The Fidesz government of Viktor Orban in Hungary and Italy’s 5 Star and Lega parties are three contemporary examples that advocate a variety of extreme actions. The leaders of Britain First, in their official policy manifestos, public statements and recorded intimidatory behaviour towards ethnic minorities, are clearly inspired by Adolf Hitler and Nazi ideology. A number of British National Party, Britain First, and English Defence League members have been convicted of offences, some violent, involving hate crimes and promulgating racial hatred. The hard-right National Action group and its supporters have been proscribed by the British government as a terrorist organization.

In addition to the hard-right, the UK Independence Party (UKIP) became a relatively softer rallying point for large numbers of disaffected conservatives who felt that the Conservative Party, their natural ‘home’, had been too weak on immigration controls and stopping perceived excessive interference by the EU in British daily life. Under UKIP’s charismatic former leader Nigel Farage, and using anti-immigrant rhetoric, UKIP and its allies managed to persuade sufficient British voters to vote for a British exit from the EU (or Brexit) in the 2016 referendum (see chapters 3 and 4). Citizens with views allied to the far- and extreme right-wing groups voted tactically for UKIP candidates in elections and have been keen Brexit supporters. The strident anti-immigrant rhetoric of some Brexit demagogues and their allies in the right-wing media is arguably incitement to violence. After the referendum pro-Brexit result, there was as an upsurge of hate crimes against foreigners and ethnic and religious minorities in the UK, including at least two murders. Just before the referendum, an anti-immigration obsessive with a history of far-right extremist views murdered the anti-Brexit Labour MP Jo Cox, as described in chapter 5.

The Editor’s Perspective

Throughout the book, the editor and primary author applies an analytical concept called ‘world-view’ that has proven over many decades to be a very useful descriptive and analytical tool for understanding the stance of particular individuals or particular groups. The modern world-view concept, or Weltanschauung in the original German, is ascribed to the late 19th century German philosopher Dilthey although it has antecedents in the philosopher Kant. According to Kluback and Weinbaum (1957), who provided an introductory glimpse of Dilthey’s proposition, world-view refers to a complex set of perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, values and motivations that characterize how an individual or group of people interpret the world, their own existence and how the two inter-relate. World-view represents a set of characteristic biases from which it is possible to predict the likely stance and behaviour of those who hold a particular world-view. However, only a small proportion of world-view as personally expressed by the individual is conscious, and pre-conscious processing (Dixon 1981) largely determines overall world-view and actions as observed by others.

As expressed above, the editor understands the world-view concept in the way typically used in the social sciences by sociologists and psychologists (see, for example, Burrell and Morgan 1979) and by other disciplines such as systems science (see, for example, Ackoff 1971; von Bertalanffy 1992; Checkland 1981; Checkland and Scholes 1990). The fine structure of world-view as recognised by such disciplines is lost in the ill-defined and variable colloquial use of the term, where it may mean simply ‘attitude’ or ‘stance’.

In addition, the disciplined use of world-view recognizes that, in ascribing a particular world-view to a particular individual or group, the analyst is influenced by his or her own world-view used as a lens or viewing instrument seeking to reveal the world-view characteristics of the subject or subjects. This process of abduction (Denzin 1978) is bound to be affected by inherent biases of the viewer. No observer, researcher, analyst or commentator can ever be free of bias, no matter how hard they may try to be ‘objective’. The art is to try to make the objectifier’s biases as explicit as possible so that readers may judge to what extent these may have affected the analysis and conclusions.

The editor values order and justice in society and believes that extremism of whatever kind is not only an affront to order, justice, and humanity but represents a real threat to democracy and, in some instances, national security. A liberal conservative, who in the Brexit context might be labelled a Eurosceptic Remainer, he rejects Alt-Right authoritarianism and extremism as much as he does that of the Marxist hard-left or any other group.

Risk and the Alt-Right Context

In contrast to other books on the Alt-Right, this book is not just a philosophical, sociological, political, or economic examination of the phenomenon but is also explicitly a risk analysis. The risk concept itself is, of course, not without controversy and the risk analysis and assessment discipline encompasses the spectrum of both pure and opportunity/speculative risks (Waring and Glendon 1998; ISO, 2018; Waring 2013). Assessment techniques appropriate to pure risks areas such as engineering, fire, safety, white collar crime and credit control may not be appropriate to speculative risk areas such as political risk, investment, HR strategy, IT strategy, foreign policy, and international relations, where more qualitative and heuristic assessment methods come to the fore (Glendon and Clarke 2016; Shrader-Frechette 1991). This book therefore adopts a primarily qualitative and heuristic approach to the Alt-Right risk narrative, using a risk assessment technique applied systematically in chapter 12.

In pursuing a risk analysis, this book recognizes that there should be no a priori assumptions about what risk exposures exist in a particular context or who is ‘at risk’ from them. Certainly, it may be convenient to assume that the Alt-Right represents a source of threat(s) to various likely parties who, therefore, may be subject to a variety of risk exposures as a result. However, such a uni-directional model is unrealistic and, indeed, a cogent analysis must also consider what risk exposures affect imputed risk sources themselves. For example, although many may regard the Alt-Right as a threat to democracy, and be alarmed at the perceived threat posed by electoral successes by populist and hard right-wing parties in recent years, the speed with which the latter voting successes may go into sharp reverse shows up a major risk exposure for such parties. For example, by May 2017 the number of UK Independence Party elected officials at both national and local levels had all but disappeared in less than a year and political oblivion beckoned. Similarly, the far-right Party for Freedom of Geert Wilders in Holland and the Front National of Marine Le Pen in France were both defeated in general elections in 2017, following years of growing success. Dubious credibility, relentless unpleasant rhetoric from such parties, and their propaganda based on fear and faked facts, are likely to eventually combine to motivate rejection at the ballot box. The risk of hubris and no longer being acceptable or taken seriously by an electorate is a political risk faced by any Alt-Right (or indeed any) party but, of course, electoral demise does not eliminate their ideology or its core supporters.

The Book’s Style, Content, Authors and Structure

This book follows academic discipline and seeks to provide evidence and references to support particular statements or at least make clear any necessary distinctions between facts, assertions, arguments and opinions. However, with such a controversial subject, and potential evocation of strong emotions (whether for or against a particular ideology or exponents of it), there is a temptation for authors to slip into polemical expression in their narratives. Indeed, there is currently an unresolved debate among academics about whether traditional scholarly neutrality must be maintained or whether authors could legitimately take a strong for/against position and use polemic in support of it. The editor took the view that the traditional approach should prevail. However, should any traces of polemic remain, he takes full responsibility for any criticism that may arise.

The potential scope for the content of a book such as this is huge and, if fully comprehensive, its size would be prohibitive. Moreover, with the inherently fast-moving nature of current affairs and developments, it is not possible to capture all relevant events and to be up-to-date, which in any event is the task of journalists and the news media. From systems science, a holistic approach only requires to include the perseverant essence of the whole and not every ephemeral component of the whole (von Bertalanffy 1972; Checkland 1981). Therefore, in deciding on content, the editor has taken a selective approach to a number of areas in an attempt to provide a reasonably representative coverage of key issues.

The book is fortunate to benefit from contributions from an eclectic group of thirteen authors with backgrounds in psychology, sociology, history, political science, international relations, and risk analysis, who variously have specialised in studies of the populist and far-right in the United States, UK, mainland Europe and elsewhere. A number have also been engaged in comparative studies of the populist right and far-right in different countries. Details of the authors’ affiliations are presented in the section About the Editor and Authors.

The book is in three parts. Part 1 on the nature of Alt-Right ideology comprises two chapters. Chapter 1 considers how best to define the evolving Alt-Right phenomenon. Chapter 2 examines the psychology, and especially the emotional origins and motivations, of the Alt-Right as an aid to understanding their behaviour and potentially predicting future actions.

Part 2 comprises nine chapters that examine how the Alt-Right ideology has been absorbed and framed by various groups in a selection of European countries including Russia, in which this ideology has made some inroads into society and, in some cases, has achieved a degree of political, if not electoral, success.

Part 3 Conclusion comprises three chapters that synthesise the various analyses from Parts 1 and 2. One chapter provides systematically a common risk analysis and assessment framework to all the risks identified in Part 2. The penultimate chapter considers how far Alt-Right ideology and practice represent a threat to democracy and western civilisation, and makes a prognosis for how the Alt-Right phenomenon might develop and how far it is likely to increase its influence. The final chapter identifies potential strategies to limit the Alt-Right threat in so far as it may exist.

References

Ackoff, R.L. 1971. “Towards a System of System Concepts”. Journal of Management Science 17(11), 661–671.

Beck, U. 1992. Risk Society—Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage Publications.

Burrell, G. and Morgan, G. 1979. Sociological Paradigmsand Organizational Analysis. London: Heinemann.

Checkland, P. 1981. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Checkland, P. and Scholes (1990). Soft Systems Methodology in Action. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Denzin, N.K. 1978. The Research Act. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Dixon, N. 1971. Pre-Conscious Processing. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Douglas, M. 1992. Risk and Blame: Essays in Cultural Theory. London: Routledge.

Eatwell, R. and Goodwin, M. (eds). 2010. The New Extremism in 21st Century Britain. Abingdon, Oxford: Routledge.

Feldman, M. and Pollard, J. 2016. “The Ideologues and Ideologies of the Radical Right: an Introduction”. Patterns of Prejudice, November 2, 2016. DOI 10.1080/0031322X.2016.1244148.

Fisher, L. 2018. “Antisemites Will Destroy Labour, Senior MPs Warn”. The Times. March 27, 2018. Pages 1–2.

Glendon, A.I. 1987. “Risk Cognition”. In W.T. Singleton and J. Hovden (eds), Risk and Decisions, pages 87–107. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Glendon. A.I. and Clarke, S. 2016. Human Safety and Risk Management: a Psychological Perspective. 3rd edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis.

Goodwin, M. 2011. Right Response. Understanding and Countering Populist Extremism in Europe. London: Chatham House.

ISO. 2018. ISO 31000 Risk Management—Guidelines. Replaced ISO 31000 (2009). Geneva: International Organization for Standardization.

Janis, I.L. 1982. Groupthink: Psychological Studies of Policy Decisions and Fiascos. 2nd edition. New York: Houghton and Mifflin.

Kahneman, D. 2003. “Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioural Economics”. American Economic Review 93(5), 1449–1475.

Kluback, W. and Weinbaum, M. 1957. Dilthey’s Philosophy of Existence: Introduction to Weltanschauungslehre. Translation of an essay. London: Vision Press.

Lyons, M.N. 2017a. Ctrl-Alt-Delete: The Origins and Ideology of the Alternative Right. Somerville, MA: Political Research Associates.

Lyons, M.N. 2017b. Insurgent Supremacists: The US Far Right’s Challenge to State and Empire. Oakland, Ca: PM Press.

Maguire, P. and Fisher, L. 2018. “No More Talk, Jewish Leaders Warn Corbyn”. The Times. March 27, 2018. Page 10.

Michael, G. 2003. Confronting Right-Wing Extremism and Terrorism in the USA. Abingdon, Oxon UK: Routledge.

Michael, G. 2016. “The Seeds of the Alt-Right, America’s Emergent Right-Wing Populist Movement”. The Conversation, November 23, 2016. http://theconversation.com.

Michael, G. 2017. “The Rise of the Alt-Right and the Politics of Polarization in America”. Skeptic Magazine, February 1, 2017. Altadena, Ca. The Skeptics Society.

Morgan, G. 1986. Images of Organization. London: Sage.

Neiwert, D. 2017. Alt-America—The Rise of the Radical Right in the Age of Trump. London: Verso.

Parris, M. 2018. “There’s a Brutish Jingoism Afoot in Britain”. Comment. The Times. March 24, 2018. Page 25.

Shrader-Frechette, K.S. 1991. Risk and Rationality: Philosophical Foundations for Populist Reforms. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Simon, H.A. 1972. “Theories of Bounded Rationality”. In Decisions and Organization, edited by C.B. MaGuire and R. Radner, 161–176. Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing Co.

von Bertalanffy, L. 1992. “The History and Status of General Systems Theory”. Acad. Management Journal 15(4), 407–426.

Waring A.E. 2013. Corporate Risk and Governance: an End to Mismanagement, Tunnel Vision, and Quackery. Farnham, UK: Gower/Routledge.

Waring, A.E. and Glendon, A.I. 1998. Managing Risk: Critical Issues for Survival and Success into the 21st Century. Aldershot, UK: Thompson/Cengage.

Wodak, R. 2015. The Politics of Fear. What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. London: Sage.

Zeffman, H. 2018. “Tensions in Labour Erupt Over Rising Abuse of Jews”. The Times. April 18, 2018. Pages 1–2.

PART 1: THE NATURE OF THE ALT-RIGHT IDEOLOGY

Chapter 1: Defining the Evolving Alt-Right Phenomenon

By Alan Waring

Abstract

This chapter examines right-wing world-views outside the realms of traditional conservatism, which are more strident, more intolerant and increasingly extreme the further to the right is their location. Populist-, far- and extreme-right parties and groups in European societies and others (e.g. Russia) are identified and characterised by nationalist, nativist, anti-liberal, anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, anti-Semitic, and white supremacist rhetoric and policies. The Alt-Right emergence in several EU countries and Russia is examined and transnational collaboration between Alt-Right groups in different countries is discussed. Collectively labelled as the Alternative Right or Alt-Right, such groups typically have a strong desire to legitimize and normalise their ideology for electoral appeal purposes. Noting the difficulties in defining the evolving Alt-Right, a working definition is proposed.

Key words: Alt-Right, ideology, nationalism, nativism, transnational, Trump.

The Conservative Tradition

Conservatism, in a general sense, refers to adherence to traditional, normative values and a reluctance to welcome change. In a political context, conservatism or the so-called ‘right-wing’ exhibits such characteristics as these found within the population, but also extends the general concept to extol the virtues of individual endeavour and self-reliance as well as favouring free enterprise, private ownership, low taxation, and socially conservative ideas. Conservatism emphasizes personal responsibility and eschews collectivism and any kind of socialist or left-wing agenda, such as an emphasis on public spending, high taxation of businesses and high earners, trades union power and a de-emphasis on defence spending.

Traditional conservatism has never been monolithic and has always included identifiable co-existing factions, ranging from the more liberal centre-right (e.g. the so-called Mainstreet Republicans in the USA; the One Nation Conservatives, Tory Reform Group and Conservative Party Europhiles/Brexit Remainers in the UK); through to right-wing conservatives, such as the Paleoconservatives, NeoCons, Tea Party and latterly Trumpists in the USA, and the Thatcherites, Eurosceptics and EU Brexiteers in the UK.

Further right still, and outside the realms of traditional conservatism, exist world-views that are more strident, more intolerant and increasingly fascist the further to the right is their location. Ultra-right parties and groups in western societies are characterised by strongly nationalist, nativist, anti-liberal, anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim and white supremacist rhetoric and policies, for example in the UK, the British National Party, Britain First and English Defence League. Similar parties and groups have arisen in many countries. Some, in view of their extremist and violent proclivities, are classed as terrorists e.g. National Action proscribed in the UK, and Aryan Nations and National Alliance in the USA (FBI, 2002). Lyons (2017a and b), Michael (2003; 2008; 2014; 2016; 2017), and Neiwert (2017) refer to a range of right-wing extremist groups in the United States. However, as discussed below, it should be noted that, although attention to the far-right is typically focussed on the west, far-right characteristics are also evident in many non-western countries.

The Alternative Right

The so-called Alt-Right (short for Alternative Right) is generally considered to encompass the spectrum of right-wing conservative world-views outside mainstream conservatism that begins with those who have become dissatisfied with the mainstream political process and character and frustrated by what they regard as the impotence of traditional conservatism. This spectrum ranges from the populist Alt-Right to all those having a hard-right, ultra-right or extremist ideology. ADL (2018) described in detail a less extreme group within the Alt-Right, which it termed the Alt-Lite. However, although informative, this distinction appears to be more pedantic than substantive. Although coined initially with reference to populist right-wing and far-right groups, ideas, and activities in the United States, the term Alt-Right has since been extended to cover similar characteristics evident in western countries generally, as well as in non-western countries such as Russia and Ukraine.

The term Alt-Right, although adopted originally in the US by Gottfried (2008) (see later), has taken on a more global coverall meaning but is not used as such everywhere e.g. in the UK. This has led to confusion in the UK, where some people call Britain First, for example, a far-right group, others call it extremist, while others call it populist. In Italy, Lega and 5 Star are often called populist yet their rhetoric and policies appear much more far-right, and some might argue extremist.

The author decided to use the term Alt-Right in this book in a coverall way simply to ensure that the spectrum of right-wing views outside and beyond mainstream conservative parties is fully captured. That spectrum ranges from populist parties not far removed from mainstream conservatism but definitely outside it, all the way through more authoritarian far-right parties and groups frequently prepared to advocate if not use violence, up to and including extremists and proscribed terrorists. The membership of UKIP, the populist Alt-Right party in the UK, undoubtedly includes many who actually profess views much more akin to the far-right Britain First and EDL—there is abundant evidence of this referred to in various chapters. Indeed, even within the mainstream Conservative Party in Britain, there have been allegations of Conservative MPs promoting far-right views e.g. Humphries (2018). Inclusion of populist parties under the Alt-Right label is necessary, therefore, since (a) the delineations between such parties and more far- and extreme-right groups are not sharp (in policy, member views, or rhetoric), and (b) there is persistent pressure by far-right groups on the more populist and even mainstream right-wing parties to shift their centre of political gravity rightwards e.g. infiltration of UKIP by Britain First and EDL activists; senior UKIP figures making racist and anti-Islamic statements reflecting BF and EDL policy and contrary to UKIP policy.

However, although the Alt-Right term is usually applied in a coverall shorthand way as above, and is how it is applied in this book, it should be noted that there are also Alt-Right characteristics evident in other countries, regimes, ethnicities, and religions. For example, the Duterte regime in the Philippines may be described as far-right authoritarian, repressive, and proto-fascist. In Myanmar, although attempting to adopt some strands of democracy following decades of absolute military dictatorship, in 2016–2017 the Bhuddist nationalist regime engaged in wholesale atrocities against, and ethno-religious cleansing of, Rohingya Muslims. Many countries in the Middle East, Central Asia, and Africa exhibit far-right characteristics in the form of quasi- or actual dictatorships, anti-democratic repression, judicial abuses, and human rights abuses. Similar charges have been aimed at North Korea and China, both of which are formally communist states i.e. far-left rather than far-right. Then there is the IS/Al Ghaeda/Boko Haram bloc of Islamist extremists who, while flying a false Muslim flag for justification, portray authoritarian, repressive, and proto-fascist characteristics strikingly similar to those of the ultra-right in the west, many of whom fly a false Christian flag for justification. For example, Michael (2006) has examined such similarities regarding the US far-right and, in particular, the seemingly paradoxical conceptual convergences between, on the one hand, neo-Nazis, Holocaust deniers, and white separatists, and, on the other hand, Islamist extremists in a number of countries. The paradox is sharpened by the fact that the Alt-Right generally in the west is anti-Muslim, and professed Islamists are generally anti-Christian. However, they share a common hatred of Jews, Israel and American foreign policy. Nevertheless, it is reported that Geert Wilders, leader of the right-wing racist Party for Freedom in Holland is a “serious case of philo-Semitism” and is very pro-Israel (Engelhart 2013)—see chapter 9. Another paradox is the upsurge in anti-Semitism in the British Labour Party, especially among the hard-left Momentum group, which contradicts the traditional anti-racist philosophy of the Labour Party (see e.g. Fisher 2018a; Maguire and Fisher 2018; Zeffman 2018).

Whereas the ideologies, strategies, tactics, and justifications used by authoritarian, repressive, and fascistic entities of whatever declaration and in whichever country appear to be remarkably similar (despite their often purported inimical differences), the scope of this book is limited to the Alt-Right as conventionally understood i.e. western countries (primarily US and European) and non-western European countries (e.g. Russia).

Table 1.1 in Appendix 1.1 lists prominent examples of Alt-Right groups in a range of European countries. The list in Table 1.1 is incomplete. New small groups arise from time to time and frequently groups alter their name or merge with other groups, especially in the United States (see e.g. Neiwert 2017). While it may appear that Alt-Right groups enjoy a large membership or level of support, typically each one has followers in the hundreds or low thousands. For example, in the US the estimated number of KKK (Ku Klux Klan) members and committed supporters in June 2017 was some 3,000 spread across 42 local groups (or Klans) in 33 states (ADL 2017). This small total compares with a national membership of some 4 million in the 1920s and between 6,000 and 10,000 in the early 1990s—see also chapter 3 in Vol 1. Similarly, in the UK, the populist UKIP’s membership peaked at 45,999 in 2015 before falling to 39,000 in 2016 and into 2017 (Keen and Apostolova 2017), and to 21,000 in early 2018 (ONS 2018). The British National Party (BNP) also fell from a peak membership of just over 10,000 in 2010 to less than 3,000 in 2016. Even at their peak, such numbers were relatively small compared to those of the mainstream British political parties and, over a period of many years, both UKIP and BNP failed to enjoy any sustained electoral success at either local or national level, as discussed further in chapters 3 and 4.

The Alt-Right is neither a political party nor is it a movement in the sense of a cohesive movement or a group having a defined philosophy, constitution, organization, policy, membership and so on. To that extent, it may be described as a phenomenon whereby large numbers of individuals, across a broad spectrum beyond and to the right of conventional conservatism and conservative political parties, share an ideology based primarily on racism and white supremacy, anti-immigration, and antipathy to perceived government interference in the daily lives of citizens. Of course, not all Alt-Right supporters are white or believing in white supremacy. For example, a number of prominent Alt-Right supporters are from ethnic minorities e.g. some former Breitbart News staffers. Nagle (2017) described the Alt-Right as a meta-group of semi-divergent right-wing sub-cultures in broad coalition seeking to overturn and replace the established order in society. Some argue that the Alt-Right is like a religious cult in some respects, as evidenced by the idolisation of particular zealots and their expressed ideas and by the invention of obscurantist language and symbols that only committed supporters are likely to understand (see, for example, Sonnad and Squirrell 2017). However, Neiwert (2017) argued that the Internet has revolutionised communication between disaffected right-wingers, especially young people, to such an extent that they are now able to rapidly encourage each other towards radicalisation and, for some, to extremism. The anarchic revolutionary zeal of some younger recruits to the Alt-Right and their fixated, self-absorbed immersion in on-line obscurantism formed the substance of the examination by Nagle (2017). Such ‘new elite’ elements are likely never to be regarded as more than an eccentric and largely incomprehensible oddity by the majority of populist Alt-Right supporters. As potential recruiters and persuaders of mainstream conservatives to move decisively rightwards into the Alt-Right, the very eccentricity, secretive language and esoteric condescension they display to outsiders is likely to weaken their appeal.

Neiwert (2017) also explained in some detail that, in common with earlier manifestations of the American populist radical right such as the Patriots and the Tea Party, the US Alt-Right movement has conjured up an alternative universe to that of verifiable reality, with alternative explanations for an entire world of known facts, and eagerness, even passion, for believing in easily disprovable falsehoods and conspiracies involving these (Kahan et al 2017; Shermer 2018). Some examples are discussed in chapters 9 and 10 of Vol 1.

Although the Alt-Right spectrum in each country is unique, a common pattern permeates them all to a greater or lesser degree:

Racism, specifically white supremacy, anti-Semitic, and anti-Muslim world-view.

Anti-immigrant priorities.

Anti-central government/anti-federalist world-view.

A fundamentalist world-view, both religious and political.

Anti-establishment/anti-government conspiracy theories.

Strident right-wing fanaticism that often spills over into social settings, Internet and social media in the form of hectoring and propaganda rants.

An over-riding hatred for such groups as non-whites, ethnic minorities, non-Christians (especially Jews and Muslims), immigrants, foreigners, liberals, socialists and other left-wingers, federalists, mainstream politicians, and bankers and financiers.

An over-riding scepticism about established science or facts of any kind that do not support, or that contradict, ideological positions and beliefs of the Alt-Right, and a willingness to believe in an alternative universe of invented ‘facts’ that support Alt-Right contentions (see e.g. Kahan et al 2017; Shermer 2018).

For example, as noted earlier, it is commonplace to hear some (but not all) UKIP supporters in the UK espouse racist, nativist, anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim positions that do not form part of official UKIP policy. This is anecdotal evidence that the Alt-Right is not monolithic and there is no fixed dogma spanning the entire phenomenon. However, the further to the right is the political party or group of an Alt-Right supporter, the more likely it is that all eight characteristics will be exhibited.

From their experimental study of how different political groups in the US respond to information, Kahan et al (2017) concluded that scepticism about truth and accuracy is (a) very much dependent on subject matter context, and (b) is biased by the individual’s pre-existing beliefs. Confirmation bias looms large in how individuals select some facts and ignore others so as to support their prejudices (Dror and Fraser-Mackenzie 2008). The eight characteristics may also be commonly linked psychologically to an authoritarian pre-disposition manifested by low curiosity, lack of open-mindedness, dislike of surprise or challenging information, taking comfort in rigid hierarchies of social and political order, feeling insecure about diversity and liberalism, and a dislike of and unwillingness to accept change that challenges their world-view.

Other more particular subsets occur that are not listed in Table 1.1. For example, one strand of Alt-Right followers are misogynists who believe that not only are they victims of government-led suffocation of their individual rights and freedoms but also that they are specifically victims of a conspiracy by government, liberal elites and feminism to downgrade men’s dominant role in society, an alleged transgression that they stridently seek to combat (see e.g. ADL 2018).

The ‘them’ against ‘us’ character evident in all the Alt-Right rhetoric and posturing across the range of different issues in the Alt-Right agenda points to an underlying paranoia in their perception of threats (real or imagined) facing them. The psychology of fear and risk and its importance to understanding the Alt-Right world-view and predictions of Alt-Right behaviour is addressed in detail in chapter 2.

The Alt-Right Emergence in the United States

Resurgent nationalism in the US, including the emergence of the Alt-Right phenomenon, is addressed in detail in chapter 3 of Vol 1 and the following is a brief introduction. Lyons (2017a and b), Michael (2016; 2017), and Neiwert (2017) provided an extensive descriptive summary of the Alt-Right ‘movement’ in the US and its rapid evolution as an increasingly populist phenomenon, from lowly beginnings and small numbers of supporters in 2008 to the unexpected electoral success of Donald Trump in November 2016 as US President. ADL (2018) provided mini-biographies of leading Alt-Right (and Alt-Lite) figures, and indicated how interconnected they and the many sub-groups and factions are. Openly committed to an Alt-Right agenda (if, indeed, he was fully aware of the full implications), and contemptuous of both the traditional conservatism of the Republican Party and, of course, the Democrats, Trump made no secret of his view that many traditional Republicans were too close ideologically to Democratic thinking. His rambling book (Trump 2015) represented a classic ‘salvation’ proposition used in sales and marketing, in which buyers are told that they have a major problem (which may be true, or an exaggeration or completely untrue) and that only the company’s product will solve the problem and save them: Trump asserted that America is crippled and that only he knows how to “make America great again”.

Nevertheless, Trump himself did not emerge politically from the Alt-Right. Rather, it is more likely that the headline-grabbing issues promoted by the Alt-Right became a convenient opportunistic vehicle for Trump’s election campaign. Trump is not a career politician and was much more interested in using the presidency to advance and promote the Donald J. Trump brand as part of a long-term business strategy. Moreover, as Lyons (2017a) and Neiwert (2017) asserted, the Alt-Right movement also judged support for Trump as an opportunity both to promote their agenda, and to weaken the Republican Party. A kind analysis is that, as President, Donald Trump became an unwitting Trojan horse for the Alt-Right, whereas a less kind analysis (e.g. Neiwert 2017) suggested that Trump was well aware of his Alt-Right role and remained more than happy to pursue an Alt-Right agenda. Either way, with no formal party and no electoral candidates, it could be argued that in the election of Trump the Alt-Right achieved a bloodless political coup of staggering proportions.

According to Michael (2017), in 2008 Paul Gottfried, a conservative academic, while addressing the H.L. Mencken Club on “The Decline and Rise of the Alternative Right”, implied that the ‘alternative right’ was a dissident far-right ideology that rejected mainstream conservatism. The latter address (Gottfried 2008) is a somewhat self-absorbed pseudo-intellectual dissection of the minutiae of what Gottfried claimed to be wrong with the right-wing in America, in particular his distaste for what he regarded as a perfidious neo-con hegemony that had marginalised Gottfried himself, and had subverted right-wing conservatism. He asserted that “We are convinced that we are right in our historical and cultural observations while those who have quarantined us are wrong”. In arguing for a vigorous resurgence of a viable true right-wing based on this certitude, and on an equal certitude of white racial superiority (e.g. “the fact that not everyone enjoys the same genetic precondition for learning”), ironically Gottfried’s elaborate discourse undermined his fervent expectation that he was creating the basis “to gain recognition as an Intellectual Right”. The so-called intellectual basis for the Alt-Right appears to be little more than an attempt to gain falsely some measure of credibility, respectability and social acceptability for what was, and is, a set of prejudiced beliefs in the primacy of inequality and the fostering of racial discrimination and white supremacy.

Nevertheless, from such small beginnings in 2008, the Alt-Right momentum in the United States took off following the appointment in 2011 of the voluble right-wing intellectual Richard Spencer as head of the National Policy Institute (NPL), a white nationalist ‘think tank’ founded in 2005. Spencer and his coterie of NPL writers have published prolifically on the white supremacist philosophy and agenda under the Radix imprint e.g. Spencer (2012). Gottfried, MacDonald and the Spencer writers arguably are the closest that the Alt-Right gets to the creation of an appearance, albeit dubious, of rational intellectual discourse.

However, the pretence of intellectualism was not central to the rapid rise of the Alt-Right. The cleverness of the Alt-Right ‘movement’ in the US, or at least those Alt-Right leaders in positions to manipulate public opinion, was to capture the growing disillusionment of broad swathes of the population about the ability, indeed willingness, of the traditional mainstream political parties to address effectively concerns about jobs, tax, the economy, health care, education etc. and lay the blame for it at the door of: (a) an allegedly weak and self-serving political establishment in cahoots with big business, and (b) the alleged predations of immigration and globalisation. The introduction in 2016 of Donald Trump, a business tycoon with no political background or experience of office, as a renegade Alt-Right Republican candidate for the Presidency, with such populist slogans as “Making America Great Again” and “draining the establishment swamp in Washington”, and “We’re gonna build a wall” (referring to a border wall to keep out illegal immigrants from Mexico and Central and South America), was sufficient to coalesce all strands of disaffected voters and get him elected in November 2016. Surrounded by an Alt-Right dominated cabinet and team of officials and advisers, the Alt-Right ideology and agenda could now be enacted.