Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

When Alexander Noble established his boatyard in 1898, he probably didn't realise he was also establishing a new Noble tradition. Alexander's yard would soon be handed over to his eldest son Wilson, who would set up Wilson Noble & Co. to build fishing boats – although he would branch out into minesweepers when needed in the Second World War. Meanwhile, second-youngest son James would break out on his own, thinking that the future of boatbuilding lay in yachts. Altogether, these companies built almost 400 boats, some of which are still working today, and would be a fixture on the Fraserburgh shoreline for nearly a century. Packed with images, interviews and recollections from the crew, The Noble Boatbuilders of Fraserburgh is a thoroughly researched tribute to these men and their boats, and is a fascinating look into an industry that once peppered our island's shorelines.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 234

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

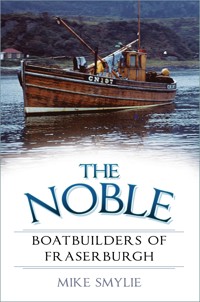

Front cover image of the Florentine courtesy of Lachie Paterson.

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Mike Smylie, 2022

The right of Mike Smylie to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9955 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Christine, PD374, in Aberdeen. (Wilson Noble)

Florentine lying at Fraserburgh in 1932. (James Noble)

Silver Crest almost derelict before she sank on Loch Ness. (James Noble)

Carrick Lass at Rye, as RX167, in about 1970. (James Noble)

Girl Irene, INS58, alongside at Lossiemouth. (James Noble)

Goldseeker. (James Noble)

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

1 A Little Bit of History

Wilson Noble & Co.

James Noble & Co.

Working in the Yard

2 The Launch of a Noble’s Boat

Wilson Noble

James Noble

3 Memories

Bobby Jones and the Sting that had Gone but Caused Alarm

The Storm of ’53: The Lifeboat Loss and Beach 13

George Forbes and the ‘Bastard Mahogany’

Strathyre, INS23

Yarning – A Few Facebook Quotes on Evangeline

4 Some Survivors

Wilson Noble: The Violet/Vesper Story

Wilson Noble: Dundarg, FR121

Wilson Noble: Sovereign, LH171

Wilson Noble: Harvest Reaper, FR235

James Noble: Harvest Reaper, FR177

James Noble: Ocean Pearl, FR378

James Noble: Maureen, WK270

James Noble: Goldseeker

5 Yard Lists for Fishing Vessels by Wilson Noble & Co.

6 Yard Lists for Fishing Vessels by James Noble & Co.

A Final Note

Appendix

Noble Boatbuilders and the Noble and McDonald Family Tree

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

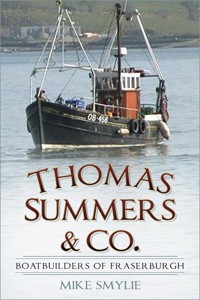

Off I had set once again, hard on the heels of the success of the Tommy Summers book, to chronicle another of the boatbuilders of Fraserburgh. As I admitted in that first book (Thomas Summers & Co. Boatbuilders of Fraserburgh, published by The History Press in 2020), it was the determination of Malcolm Burge and Alexander West that drove the project on. This time not much had changed, which was why I was propelling myself north again once the pandemic restrictions had somewhat eased.

And so I arrive in Mallaig, that ‘doyen’ of the West Highland herring, and I find myself staring down at Stella Maris, PH97, ex-Iris, FR7, built by James Noble in 1968. She has that old withered look about her, tired wheelhouse and deck resulting from years of hard toil. My phone rings and it’s my old mate Luke Powell, wooden boatwright extraordinaire, in Mallaig with his new-build Pellew, a replica of a Falmouth pilot boat. I spy her huge mast over the fishing boats, in among the plastic yachts in the marina.

Powell builds wooden boats with a vengeance and is largely responsible for the growth in new wooden craft. But he always teases me and this time is no exception.

‘Why aren’t you writing about getting people to build new fishing boats in wood rather than all that stuff about history?’ He talks like he’s lamenting the end of an era, which I guess is pretty close to the truth. He, along with a couple of others, doggedly refuse to give up on wood for the construction of ‘working boats’, even if their description of ‘working’ means ‘chartering’. Yet, their new vessels prove that wood remains a viable material for large vessels and he wouldn’t be the first boatbuilder to state categorically that they could build an under-10-metre for a price that matches steel.

So I prevaricate that I leave that sort of talk up to ‘you boatbuilders’, even if, in my heart, I know he’s right. I look at some of today’s steel new-builds and I see nothing of beauty of any description in them. Yet the curves and shape of a wonderful wooden fishing boat please almost everyone’s eyes!

My own eye moves to the slipway, where I see Prevail, a wooden vessel that sank in Stornoway and was written off, ready to be unceremoniously dismantled until John Wood took her on to restore her as a working vessel. John has already reincarnated Crimson Arrow, KY142, ex-Maureen, WK270, built by Jimmy Noble, and was fishing her from Mallaig until a week before. Sod’s law, I guess, that I’d missed her.

Powell’s comments lie heavily on my mind as I travel north. Arriving at Isle Ewe boats, I can only feast on the sight of the Lochfyne skiff Clan Gordon under restoration, a vessel whose fortunes (and misfortunes) I’ve been following ever since I sold my own Lochfyne skiff Perseverance, CN152, to owners who then sank her in the Atlantic.

Then to Ullapool, where I find another vessel, St Vincent, 405CY, at the loch-side yard of Johnson & Loftus, being restored, both these being funded by the same source. Both were early builds (1911 and 1910 respectively) and both worked these West Highland waters.

Finally, and the whole reason for being here, I meet the Noble-built Goldseeker, the 1967-built fishery research vessel, financed by the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries for Scotland, to work mostly, I believe, along the west coast. She moved to private hands in 1993 and today is owned and kept in wonderfully tip-top fettle by Scott Coleman and Robyn Thegrate. Simply boarding her at Ullapool’s pier, the boat instantly exudes its unique vintage, like a fine wine, so that I breathe in and imbibe! She truly is a gem, almost original except for some internals, complete with her original Gardner 6LX purring below.

We cast off and head out into the loch, viewing a couple of the wrecks along the coast, including the Tommy Summers’ Easter Morn. Down to the lighthouse at Rubha Cadail before turning for home, just enough time to get the feel of her even if the sea is calm. When we part, I feel I know the boat for some weird reason. But it is enough and, with the usual tear when leaving the west coast, we head east. To the Broch then, where these workhorses started out and hopefully to the last remnants of the story that has been growing over the lost months of the pandemic …

As usual there are many people who have been instrumental in this book. First off have to be Alexander West and Malcolm Burge, who started the whole Facebook thing, and Malcolm for his continued work on it.

Then I must mention the Scottish Fisheries Museum, and Linda Fitzpatrick in particular, where most of the work detailing the lists for each yard was undertaken. Obviously here we are only talking about the Wilson and James Noble lists, but they’ve also completed the Tommy Summers and J. & G. Forbes ones.

Bill MacDonald, Benny Noble and Chris Reid from the Fraserburgh Heritage Centre, where the Tommy Summers book was launched just before this pandemic began to take hold of us, have been helpful. Bill MacDonald’s 1992 book Boats & Builders: The History of Boatbuilding Around Fraserburgh has been vital in understanding these yards.

Noble family members have provided much background of the individuals in the firms. These are Wilson Noble junior’s daughter, Maureen Small; Charlie Noble’s sons, James and Charlie; and Maureen and Bruce Herd, Yankee’s daughter and her husband.

For his memories of both yards (and Tommy Summers’), 88-year-old Bobby Jones was priceless, thanks to help from Crawford Rosie, who took me to meet him after I’d listened to various tales they had recorded together over the lost months of the pandemic. It really was a pleasure to meet you, Bobby!

To Alastair Noble of Girvan and his father Peter, who sadly passed away during the writing of this book, thanks for the family memories and connections.

For snippets of information, I mention Willie Whyte, Charles William Forbes, Jimmy and John May, Willie McRobbie, George Forbes, George Westwood, Fred Normandale, Simon Sawers and Mary Melville. Then Billy and John Wood for their information (and determination) on the restorations of Crimson Arrow and Crimson Sea.

To Ocean Pearl, whom I first met, thanks to Michael Custance and Nick Gates, many years ago.

To Scott Coleman and Robyn Thegrate for introducing me to Goldseeker.

To my daughter Ana for keeping me sane during our week-long trip around Scotland, and Luke Powell, Adrian Morgan and Rory MacPhee for sustenance during that trip. I’ll add boatbuilders Alasdair Grant, Tim Loftus and Dan Johnson who understand these boats, simply because I can!

For photographs, first Lachie Paterson for sharing – no, drip-feeding – me a wee bit of the wealth of his extensive photo archive, and to Angus Martin for edging him along.

Family photos have come from Maureen Small (Wilson’s) and Maureen and Bruce Herd (Jimmy’s). Not to be omitted are Maureen Herd’s brother, Martin McDonald, and his wife, for organising and transporting the family photos back to Scotland from Houston where they live.

Then Darren Purves for accessing some wonderful 1970s slides, as well as allowing me to use some of his own (and his son’s!) photos. Finally Willie Mouat, Finlay Oman and Peter Drummond, who kindly sent me some from their collections. Last of all, all users of the ‘Wooden Boats by Wilson Noble’ and the ‘Wooden Boats by James Noble’ Facebook sites, where the majority of the photos, along with snippets of information, have come from. It was widely publicised that they would be used in the book and several people came forward, and their photos acknowledged. Others have also been credited where the photographer is known. If there are omissions, for which I apologise, please contact the publisher so that this can be rectified in any future reprint.

Finally, my thanks to Amy Rigg at The History Press for her art of persuasion to get this book off the starting line, and the subsequent job to get it into anything resembling sense!

1

A LITTLE BIT OF HISTORY

Fraserburgh – originally an amalgamation of the harbour of Faithlie, first built about 1547, on the eastern side of the north-west tip of Aberdeenshire and the fishing village of Broadsea (originally Seatown) to the north-west around the bay – was laid out as a new town in the sixteenth century by the local landowning Fraser family of Philorth. Hence, Fraser’s burgh or ‘Frazersburgh’, as one map-maker put it in 1747, a time after it had become a Royal Burgh in 1601. Built to compete with Peterhead and Aberdeen, it was initially the herring fishing, and subsequently the white fishery, that created the harbour (and town) as it is now. But it was Broadsea that was originally the home of the fishermen and, in 1789, it had forty-two working off the beach with small open boats, twenty-nine of whom were Nobles. There were seven boats crewed by six men in each, and they sailed as far as Barrahead in their search for fish.

Faithlie was little more than a couple of quays surrounding a sandy beach where boats could be drawn up and, prior to the nineteenth century, was the domain of soldiers and trading boats. Presumably it was exposed to the south-east. By the early nineteenth century the North Pier had been extended and the South Harbour added. This was a time when the herring fishing was expanding rapidly after Government intervention in the 1790s. Fraserburgh then became an important herring station during the early summer season and, presumably, the Broadsea men based themselves there.

By 1815 bounties for the herring fishing had been introduced for small craft and the east coast of Scotland’s herring fishing turned from being a cottage industry to a commercial fishery. That year, as John Cranna tells us in Fraserburgh, Past and Present:

The boats had no decks whatever, and measured about 20 feet of keel and 12 feet of beam. The crews depended as much upon the oars as the sails for going to and coming from the fishing grounds. The craft never went more than a few miles from the shore in quest of the herring. This accounts for the comparatively small loss of life at sea in these early years. Caught in a gale thirty or forty miles at sea, these cockle shells would have instantly foundered, with results which need not be conjured up. The crews, however, excellent judges of the weather, kept the harbour when lowering clouds appeared, and if at sea, smelt danger from afar, and promptly sought the friendly shelter of port before the fury of the tempest overtook them. Thus were they able nearly a hundred years ago to prosecute their calling in comparative safety, frail though their boats were.

Further developments in the nineteenth century created a much larger harbour as the herring fishing flourished. The number of boats participating in the herring fishing in the district increased rapidly so that by 1830 there were 214 Fraserburgh boats, twenty-four from Peterhead and thirty-four from Rosehearty. This suggests that there were only local boats working out of the harbour, although Cranna reports that boats came from the Firth of Forth and a few from the north. At the same time, as Cranna mentions, there were thirty fish-curing yards dotted around the town:

in the most out-of-the-way places. Messrs. Bruce, for instance, cured on a little bit of ground facing Broad Street and Shore Street, immediately to the south of the Crown Hotel. Curing plots were being freely let off at the entrance to the Links, about or near where the railway station now is, and several firms cured there. The trade was slowly but surely consolidating at Fraserburgh. In the year 1830 the catch of herrings in the Fraserburgh district, which included Peterhead, etc., touched the very respectable figures of 56,182 crans, while the number of curers for Fraserburgh alone was 30, being two more than in 1828.

Boat design was altered after the great south-easterly storm in August 1848, when many fishing boats were lost along the east coast and there were many fatalities among the fishers. Many were overcome by the sheer force of the waves when returning in the face of the storm to unsafe harbours, although it seems that the Fraserburgh men survived whereas in Peterhead there were thirty-one casualties and twenty-eight boats wrecked. The storm forced Parliament to act and the subsequent report submitted by Captain John Washington made various recommendations in regard to harbour improvement and vessel design, as well as the phasing out of plying fishermen with whisky in part payment for their labours! However, Fraserburgh did have its own storm to remember, in 1850, when a north-westerly gale forced boats onto the sands. Nevertheless, only one life was lost, with ten boats driven ashore.

In the harbour, the Balaclava Pier was added over the Inch Rocks in the 1850s to create more protection and later the South Pier was built, followed by the Balaclava harbour works. Boats also became larger due to improved building techniques in carvel construction, where planks are laid side by side instead of overlapping or clinker (clench) building. Decks were added to the previously undecked craft, affording greater seaworthiness and safety at sea.

As more and more men were enticed into fishing – what else was there? – the demand for fishing boats grew, as that for did trading vessels to carry the herring off to markets. With the arrival of the railway to Fraserburgh in 1865, allowing fish to be carried away to the centres of population such as Edinburgh and Glasgow, the landings increased rapidly. Some maritime industries suffered – sail-making and rope works in the main – as these commodities could be produced elsewhere cheaper, but Fraserburgh saw no incoming industrialisation on a large scale.

Fishing became the main occupation of the second half of the nineteenth century, aboard, at first, the great Zulus and fifies, with their powerful lug rigs, then with the introduction of steam drifters and trawlers. In the 1880s there were some sixty curers working in the town. On one night in July 1884, 667 boats landed 20,010 cran of herring, and the herring lassies were kept busy processing this catch into barrels. But such was the enormity of the catch, and the fact that the fish were small, that even though they worked all night, the women were unable to gut it all. With more being landed the next day, some 4,000 cran were dumped in the harbour and plenty more was carted to farmers, who laid it on their fields as fertiliser.

Fish processing (an improvement from ‘curing’), an important part of the industry, supplied the British army with rations in the Boer War and again in both the First and Second World Wars. In the early 1920s, with the advent of the internal combustion engine, so began the last great development in wooden fishing boat design with cruiser-sterned herring drifters, canoe-sterned ring-netters, double-ended seiners, leading to, later, transom-sterned craft as motor power increased. Further harbour expansion brought about the Faithlie Basin, the completion of which ended the expansion of the harbour, although improvements continued and do so right up to this day.

Needless to say, the provision of boats needed boatbuilders and Fraserburgh has had some well-known names in that respect over time. One of the first documented was a Mr John Dalrymple, a member of a family that came to Fraserburgh from the Firth of Forth, who had a facility at Black Sands in the early nineteenth century. They, it is said, had seen an opening in the quickly expanding herring fishery.

Another was John Webster, described as a shipbuilder, who employed fifty carpenters and who commenced work in 1840 but had ceased by 1887. It appears he was originally from Aberdeen but chose Fraserburgh to set up his yard. Over this period he is said to have built at least fifty-seven vessels excluding local fishing vessels. His last boat was Shiantelle, built for renowned naturalist J.A. Harvie-Brown for his expeditions to the western and northern Scottish Isles for the years up to 1891.

Mr Weatherhead – a name well known further south – opened a facility in about 1884 in a location by the Kessock Burn, which would have been in the vicinity of today’s Kessock Park. This appears to have been the first recorded yard in Fraserburgh devoted to the building of modern (of that era) fishing boats. However, the location of the premises Weatherhead worked in made launching boats difficult, given they had to be hauled over to the beach by horse. This yard had closed by the turn of the new century.

In 1890 two men, both of whom had been apprentices for Webster, took over his dilapidated yard and set themselves up as Scott & Yule. This company was, according to Cranna in 1914, ‘kept very busy building fishing boats known as steam drifters, which in some measure, fills up the gap caused by the collapse of shipbuilding’. However, within a year the yard had closed – maybe a reflection of the general state of shipbuilding. Records supply us with details of at least eighteen steam drifters built between 1907 and 1915.

Broadsea man Alexander Noble had served his apprenticeship with Weatherhead’s. When Scott & Yule took over Webster’s, Alexander Noble was soon to join their workforce. Eight years later, in 1898, he decided he wanted to branch out on his own and set up a small boat repair yard at the foot of the Royal Hotel Brae. He was obviously well known locally and fishermen persuaded him, it seems, to commence boatbuilding, for which he needed larger premises. He moved to a yard in the Balaclava Basin, adjacent to the Provost Anderson’s Jetty, where he launched the Sincere, FR909, for Robert Duthie in 1899. This was soon followed by the 70ft fifie Victoria, FR971, for Broadsea owners G. Noble & J. Buchan. Victoria was a successful boat and a story emerged that, as long as Victoria was sailing, the yard would continue to prosper.

Alexander, known as Cocky, was the son of Alexander, known as Auld Cocky. He married Elizabeth, whose maiden name was also Noble, and together they had eight children: Wilson, Alexander, James, Charles, Magdelene, Elizabeth and two others who died in childhood.

Despite initial success, in 1901, Alexander Noble handed over the running of the yard to his eldest son Wilson (sometimes also referred to as Cocky), whom he deemed was more interested in the business side of running a busy yard. Wilson had served his apprenticeship as a cabinetmaker in Fraserburgh, as had his younger brother Alexander, and both worked in the yard after their apprenticeships had concluded. Thus the name of the yard then became Wilson Noble & Co.

Two adverts for the consolidated Pneumatic Tool Co. Ltd (known locally as ‘Toolies’).

WILSON NOBLE & CO.

After Scott & Yule closed down in 1915, Wilson Noble & Co. was left as the only boatyard in Fraserburgh building fishing boats, while down the road in nearby Sandhaven, Forbes was successfully plying the same trade as it had since the 1880s. In 1902, George Forbes, the founder, handed over to his sons James and George and the name J. & G. Forbes was born. It was a name synonymous with fishing vessels up to the yard’s closure in 1990, although Forbes did retain a repair yard in Fraserburgh harbour.

To recap, Wilson Noble had three brothers Alexander (b.1886), James (b.1891) and Charles (b.1893). He was the eldest, having some five years over his nearest brother, Alexander, and was married to Rachael Grant Cardno. Together they had four children: Wilson junior, Mary, Margaret and Alexander, known as Zander. Margaret and Zander were twins, while Wilson junior was the youngest of all.

Although Wilson – known locally as Cocky, as mentioned – and Alexander were running the yard, both James and Charles served their apprenticeships there. The early part of the twentieth century was a time of change in fishing boat design. Such craft had grown in size in the latter part of the nineteenth century thanks to changes in techniques and the availability of heavier and longer pieces of timber. Carvel construction, whereby planks are laid onto a backbone of frames, superseded clinker construction in most larger craft. The advent of steam-driven vessels demanded larger craft. In Fraserburgh and the surrounding area, there were generally two types of sailing fishing vessel still working: the upright fifie type and the more progressive and faster Zulu type. Both were considered as immensely strong and seaworthy fishing vessels, used mostly in the pursuit of herring, while smaller craft were working long-lines for white fish and creels for shellfish. Steam-driven vessels were, for the moment, restricted to trawling and drifting, although the Fraserburgh fishermen were slow to catch on. Thus we believe that the first wooden steam drifter built in the harbour was in 1907. Which yard was responsible is unclear but the first Noble-built steam drifter was the 90ft Gowan, FR232, launched that year, followed by the slightly smaller Kinnaird, FR205, later that year. That was in the days before the covered yard was built. When the Kinnaird was launched, it is reported that part of the quay was chipped away to facilitate the launch off the quayside. That year, between the three Broch yards in operation – Wilson Noble, Scott & Yule and Forbes of Sandhaven – Fraserburgh boatbuilders launched twelve steam drifters.

A dapper Wilson Noble with his wife, Rachael. (Maureen Small)

Rachael and Wilson Noble. (Maureen Small)

A few years later, in 1911, Wilson Noble launched two well-documented sister ships: the small Zulus Violet (FR451) and Vesper (FR453). Although not as long as the true first-class Zulu of the late nineteenth century, when such vessels were over 80ft long with massive overhangs at the stern, nonetheless both these vessels were 45ft overall and have been termed ‘half-Zulus’. A note of caution: although I term them half-Zulus because, in my opinion, they are not the larger first-class vessels and tend to only have one dipping lugsail whereas the large craft had two massive sails on equally massive spars, there are those who insist on the Zulu label for all vessels with a raking sternpost, angled at some 45 degrees. Personally I disagree, believing the whole point of terminology is to critically evaluate, and thus group, vessels of equal stature. Regardless, they were both long-standing vessels and Violet survives to this very day in the US (see Chapter 4: ‘Some Survivors’).

There are very few records of other boats built prior to the First World War, although we can only assume that the yard was turning out a handful each year, especially when fishing was booming. However, we do know that White Oak, FR558, was launched in 1913 and Violet Flower, PD148, the following year, before the outbreak of war. Kinnaird foundered in Loch Eport in 1930, and Gowan and White Oak survived into the 1930s, whereas the 91.5ft Violet Flower wasn’t scrapped until 1947.

The family: L–R Wilson, Rachael, Mary, Margaret, Wilson junior and Alexander (Zander). (Maureen Small)

The family again in more formal stance. (Maureen Small)

During the war itself, although records are again scarce, we do know that Wilson Noble built at least ten steam-driven Admiralty vessels, and converted many more. Only details of two of these drifters remain: Mackerel Sky and Milky Way, both close to 90ft long. After the war, both went into fishing on the east coast until being scrapped in 1951. Presumably the others were similar in design. Three were completed after the end of hostilities in 1919–20, when there was a brief post-war boom in the fortunes of the harbour.

It was at this time that another Alexander Noble (though of no known family relationship) was brought to the yard at six o’clock one morning in 1919 by his fisherman father Peter Noble and was apprenticed to the yard under the guidance of Cocky. In his National Maritime Museum monograph (no. 31, 1978) entitled The Scottish Inshore Fishing Vessel: Design, Construction & Repair, this Alexander Noble notes that he was 14 at the time and that ‘the firm employed about eighty men’ on the Monday morning that he turned up for work. After serving his time, and perhaps a further spell in the yard, Alexander moved west in 1933 to take up a position as foreman in a yard in Killibegs, Ireland, before returning to Scotland four years later to work with James A. Silver, yacht builders at Rosneath. Part of his work was the repair and maintenance work on Clyde-based ring-net fishing vessels, some from the Girvan area. After almost a decade at Rosneath, Alexander, along with his son James, set up Alexander Noble & Sons Ltd of Girvan, a yard renowned for its fishing vessels and one still surviving, in part on fishing boat maintenance (see Built by Nobles of Girvan by Sam Henderson and Peter Drummond, published by The History Press, 2010).

Whether there is a blood connection between the Fraserburgh and Girvan Nobles still remains to be seen, even if we do know about the apprenticeship link. The Girvan Nobles have traced their ancestry back to another Alexander Noble, who was born in 1609 and lived at 84, Broadsea, Fraserburgh, and was still living in 1690. He became the first harbourmaster of Peterhead’s harbour, where the initial construction of what is today’s Port Henry Basin began in 1593. Common sense tells us that there’s a good chance of a family connection in the intervening ten generations!