3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

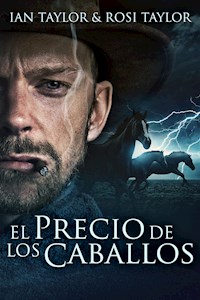

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

After his mother and sister are killed in a trailer fire, Luke Smith turns to thievery to raise money and protect his people from oppression.

In the world of gypsy travelers and underworld brigands, danger is never far away. When a burglary goes awry, Luke is pulled into a web of lies and deception that reveals a stunning truth.

Trying to set things right, Luke has to balance between justice and revenge. But in the end, which will prevail?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

THE PRICE OF HORSES

or

Revenge is a Dangerous Road

by

Ian Taylor and Rosi Taylor

Some horses might cost you your life

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Postscript

You may also like

About the Authors

Copyright (C) 2019 Ian Taylor, Rosi Taylor

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Edited by Wicked Words Editing

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

For all true dromengros, past, present and future

1

The country lane lay quiet in the lingering evening light of early summer. The leaves of the oaks and hawthorns in the field hedgerows on each side hissed softly in the gentlest of breezes. The sun was slowly sinking below the horizon, leaving mottled bands of alto-cumulus to the northwest glowing violent orange-red, like the reflection of some far-off conflagration. With barely audible flutterings, nesting birds settled down into exhausted sleep, the long day feeding hungry fledglings over for a few brief hours.

A Romany travellers' trailer with ornamented chrome work and steel trims stood on the grass verge. Voices and laughter drifted from the open door. A small truck was pulled up nearby. Between the truck and the trailer, an open fire burned brightly. Above the fire a blackened kettle hung from a kettle iron. A smooth-haired brown lurcher, tethered by the trailer, watched everything that moved.

Further down the lane, a dozen piebald gypsy vanners, tied to their plug chains, grazed the coarse grasses on the verge. The munch and stamp of the horses and the rattle of their chains as they grazed was at first all that could be heard. Then voices arose, strangely disembodied among the dense screen of hawthorns.

Luke Smith, a fifteen-year-old Romany youth, and Riley, his elder brother, worked among the bushes, grooming the family's prize chestnut mare. Riley brushed the mane, Luke the tail. Seniority in such tasks was strictly observed.

"You done good mushgaying, brother?" Riley asked. "There's no posh rawni's gryes in the field? No bokros and gurnis?"

"I've dikkered every inch of it!" Luke replied hotly. "No sheep. No cows. There's only drummers as round and fat as firkins! And a couple o' snoring elephants."

Riley was used to his brother's strange mixtures of fact and fantasy. "We'll put Nip in later to get us a drummer."

Rabbit stew for supper! We'll be living free as princes!" Luke exclaimed.

By the trees across the lane, Old Musker, a tramp with a bushy grey beard, erected a small, hooped bender tent. He kept up a muttered commentary in traveller cant as he worked. No one knew Old Musker's age; he had been announcing that he was "nearer seventy than sixty" for as long as anyone could remember. He had attached himself to the Smith family for the past year, and in spite of him not being of their blood, they had kept him fed and watered. But he always set up his bender at a distance, as privacy mattered, too, on both sides.

Ambrose Smith, the youths' father, a dark wiry man, stepped out of the trailer, followed by his wife, Mireli, and Athalia, his thirteen-year-old daughter. Both mother and daughter wore brightly patterned dresses, with headscarves over their long glossy black hair. Ambrose was in his weather-worn work jacket and heavy boots, his flat cap, shiny with time, set at a jaunty angle.

He glanced at the sky. "Be a dark moon tonight. Reckon we'll get ourselves some free grazing." He gave a short whistle as a signal to his sons and waited until they emerged from the trees. "It's a beautiful evening, with only us here to please ourselves. Unplug the gryes, boys. We'll be putting 'em in that empty meadow yonder."

Mireli cautioned them. "Riley. Luke. Look after the gryes. And your dadu. They's all we got!"

"Let me come with you!" Athalia pleaded.

"Your job's to take care o' your dai, my girl," Ambrose admonished her with a kindly smile. "She's all we got!"

Luke, handsome and easygoing, laughed at her. "We're only gonna nick a little gorgios' grass, a bit o' chaw ta pani. It's no big deal."

Riley, habitually scowling, took exception as usual. "Big deal? This Romanichal's a yank now!"

Ambrose waved to the women, who watched their menfolk leave. Mireli glanced at the lurcher. "If anyone comes prowling, Nip will tell us."

The lurcher looked up at them at the mention of his name.

Mireli waved to Old Musker. "Drop o' tea when you want."

"Two minutes!"

Mireli knew that clock time to Old Musker meant nothing. Two minutes could become as many hours. But she topped up the kettle from the water jack, placed more wood on the fire and got the drinking mugs ready.

"You think Musker will live another year?" Athalia asked her mother as they went back into the trailer. "What if he dies? Where will we bury him?"

"He said he wants to be laid in the churchyard in his village, or his mullo, his ghost, won't let him find peace. He told me he'd paid for his grave years back. Next to the birch tree he said, so he could be a part of its roots and travel in the underworld. But I don't know if he was just telling a mumpers' tale. Anyhow, who says he'll be dying? We're looking after him now."

Riley and Luke released the horses from their plug chains and walked them for a quarter mile to where Ambrose had opened a field gate to let the horses enter the wildflower meadow that bordered the lane.

"Be some sweet grazing for 'em tonight," Ambrose remarked. "It'll help get 'em in shape for Appleby Fair. We've to meet Taiso there next week."

Luke looked at their prize mare with pride. "I ride her over the field?" he asked eagerly.

Riley frowned. "What makes you think you can?"

Luke grinned. "I can ride anything! I could ride a wild boar if we'd any left in England. Or even one o' them African osteriches!"

"You be riding for a fall!" Riley seemed about to punch his younger brother. Luke stepped back, laughing. He enjoyed annoying Riley, but the fun was beginning to sour, as increasingly he was growing to think of him as weak—and only a bully makes sport of a coward.

"Freedom's wasted on you, brother. You gotta live it or lose it! One o' these days you'll wake up and wonder where it's gone!"

Before Riley could reply, Ambrose stepped between them. "Wait till we get to Appleby. You can ride her there, both o' you. It'll help us sell her. Too risky to ride her down here in the dark. She might get a hoof in a drummer's hole and go down. Then where'd we be?"

Ambrose, a man of practical good sense, was right, of course. His mind was filled with nuggets of wisdom, the fruits of forty years on the road. Luke stored his father's observations away like a secret coin hoard, but he also picked up something else: a sense of sadness that hung around the man like an invisible aura with no obvious cause. While Luke chased the impression away like an irritating bug, Riley seemed to have no power to banish it. Sometimes it seemed he was sucked into their father's sadness, as if the two of them were privy to some disturbing secret.

But Luke's enthusiasm remained undiminished. "Can I swim her in the Eden at Appleby, Dadu?"

"We'll see," Ambrose said thoughtfully. "We'll mebbe race her in Flashing Lane. If she wins, we'll get a good price for her."

They stood a while, watching the vanners gallop around the field, enjoying their freedom. As the light faded, the horses settled down to graze and drink at the field trough. Then, at last, the chestnut mare was put into the field.

"Beat you at Appleby this year, brother," Luke taunted Riley good-naturedly. "You'll be a loser!"

"Loser?" Riley scowled. "Another word for gorgio, ain't it?"

They all laughed. The sound of two gunshots, followed by a sudden explosion, took them by surprise. Flames leaped into the sky in the direction of the trailer.

"Dordi! Dordi!" Ambrose exclaimed. "Run, boys! Run!"

They closed the field gate and sprinted towards the fire. Luke raced ahead, Riley and Ambrose a stride behind. Gradually becoming visible through the lane-side trees were flames engulfing their campsite.

The trailer was a fireball. Old Musker and Nip were nowhere to be seen. Luke, Riley and Ambrose tried to get close, but the heat beat them back.

"Mother! Athalia!" Luke yelled. He leaped forward, as if about to hurl himself into the flames.

Ambrose grabbed him and held him back. "It's too late, son. We're too late. We've lost our dearest treasures."

They stared helplessly at the inferno that had once been their home, tears streaming down their faces.

Luke released a terrible yell of despair. "Who's done this to us? Who's done this to us, Dadu?"

His father and brother stared in despair at the flames. They shook their heads but made no reply.

"Who's done this?" Luke persisted. "Who hates us so much?"

"No one," Ambrose managed to reply through his tears. "No one's done it." He looked at Riley for confirmation.

"An accident," Riley said, his voice choked with emotion. "Just an accident. Those gas bottles are dangerous things."

Luke didn't believe them. He couldn't explain how he knew, but their words were hollow.

"Who's done this?" he yelled again.

"No one, Luke. Believe me."

"An accident, brother!"

But Luke's mind was screaming NO! NO! NO! "Who hates us so much, Dadu? I swear by my blood I will find them and kill them!"

2

A derelict four-storey Victorian building stood close to the centre of a city in the English Midlands. Brick-built but crumbling a little, it was screened off from the surrounding streets by a solid eight-foot fence topped with razor wire. A few broken windows could be seen on the building's upper floors, and a long row of pigeons perched on the roof ridge like architectural adornments. Across the front of the building were the faded words RADFORD BUILDING SUPPLIES.

An area of cracked concrete surrounded the building inside the fence with, to one side, a range of repair shops for the firm's vehicles, which were now long gone. The yard, which had once held breeze blocks and soft sand, was empty, as was the cement and plaster store. In front of the repair shops stood two travellers' trailers occupied by the current minders, who were there to prevent raiding or squatting by the city's opportunist elements. Everything of value, which was mostly copper wire and items of metalwork, had already been stripped by the minders.

The site's owners, who themselves had gypsy traveller connections, had no wish to see their property overrun by gorgios. They were waiting for the outcome of a planning application to turn the site into a creative centre, which included a cinema and live performance space. If that was refused, plan B was to transform the building into flats, with retail units on the ground floor. Much less imaginative.

The families in the trailers were Boswells, who had been pleased to let one of their extended clan occupy part of an upper floor as an added deterrent to intruders. The single male occupant kept himself to himself, rarely intruding on the families in the trailers, nor they on him.

There was little evidence that anyone lived on the fourth floor. One end of the floor had been tidied up. A set of wooden shelves that had once held rainwater fittings was now a store for cat burglars’ equipment: screwdrivers, lock pickers, knives, torches, ropes and straw packaging. A frameless rucksack and a neat pile of clothes lay at one end, and a simple pallet bed was spread on the floor.

Luke Smith, now thirty, had grown into a tall, athletic, muscular man, with black shoulder-length hair. Dressed in joggers and T-shirt, he lay asleep on the pallet bed one mid-afternoon in early summer, having driven up from the Wickham horse fair that had been held the previous day. He had bought two dull-spirited cobs at Wickham, groomed and ridden them, using his natural talent to coax them back to energetic life. Then he had sold the transformed animals for twice what he had paid for them. It had been a good day.

He was something of an outsider in the gypsy travelling community, an enigma around which dark rumours circulated. How did he make his vongar, his money, travelling folk asked? Why was he so secretive? Where had he learned his undoubted skills with animals? Luke did nothing to dispel the mysteries; rather he encouraged them by his sudden appearances at travellers' fairs and by his equally abrupt vanishings.

He had a reputation at the fairs for a certain degree of honesty, which, broadly speaking, was rare. Anyone who bought a horse, a dog or a hawk from him more often than not got good value for their investment. He had plenty of travellers' tricks when it came to enhancing the appearance or disposition of an animal, but he also had something else, which the rumours described as a gift, some going so far as to say he had a magical touch.

This particular rumour started years earlier at Stow fair, where he had come across an acquaintance in a state of despair and on the brink of furious tears. It turned out that a horse the man had bought earlier in the day had collapsed an hour later and seemed at the point of death. Luke had offered to buy the horse for half what the man had paid for it. The traveller eagerly accepted the deal, thinking the young man must be a bit simple in the head. An hour later, the same horse was sold for more than twice what the man had paid.

“How did you do it, mush?” the traveller asked resentfully when he came across Luke later in the day, having heard the price the animal had been sold for.

“I talked to him,” Luke replied, looking serious. “I told him it was no way to behave, and he was letting his bloodline down getting sick for no reason. He decided to get up to prove me wrong!"

The traveller shook his head, not knowing what to believe.

Luke didn't mention that the animal had been drugged by his good friend Sy, who just happened to meet its unhappy buyer when the horse was sinking to its lowest ebb. Luke had bought the vanner and immediately administered the herbal antidote, plus a secret remedy he had gotten from an old horseman whose ancestors had been members of the East Anglian guild. Half an hour later, the animal was as lively as a horse of his mature years could be.

"It was magic, I tell you!" the gullible traveller insisted that evening in the pub. "I've never seed a grye changed like that!" The rest, as they say, is history.

The police had Luke's mugshot on file, as he had been brought in for questioning a dozen or more times in connection with daring burglaries that involved "unprecedented" climbing feats and "inconceivable" escapes if the alarm had chanced to be triggered. He had never been convicted, and, by rights, his photograph should not have neen retained. But he was the source of much official frustration and the desire—perhaps even an obsession—in several constabularies to put him behind bars.

His reputation as a cat burglar extraordinaire was based on one brief frame of surveillance footage where he emerged from a property in West London's stockbroker belt in the act of pulling his balaclava over his face. It wasn't enough to put him in court, but the rumours spread like a virus from one constabulary to another until burglaries involving difficult climbs were rated as a Luke Smith five or a Smith eight.

The world beyond Radford’s was full of him, but no one knew very much about him, at least nothing that was certain, including where he lived. The minders in the trailers, when they heard the latest “factual” rumour, thought it was all hilarious. Luke himself characteristically said nothing…

His mobile rang. He was awake and on his feet in one bound, snatching the phone from a shelf.

"Tam! How you doing, mush?"

As he talked, he moved to a grimy window and looked out. It was his favourite pastime. From his vantage point, views extended from the railway station and bus terminus to the inner ringroad and, beyond that, to the distant suburbs. On the skyline to the north, about ten miles distant, he could see the vague outline of woodland, almost obscured from view by the intervening smog of exhaust fumes.

What held his attention was movement: the mainline trains entering and leaving the station, express coaches to distant cities making their way from the bus terminus, threading their route out of town to the motorways. Movement was something he understood. It was in his blood, going back more than a thousand years to the time when his people roamed the desert and hills of Rajasthan.

Hidden in his secret eyrie, he spent hours watching movement. He had observed the flights of geese and wild duck through the winter months, carving their passage between the city's waterways and their feeding grounds in the surrounding countryside. Whenever he saw the birds, his own wild spirit leaped to greet them, as if he was about to join them on their timeless journeying.

Closer to his base were the flights of the resident urban birds: the jackdaws that roosted in the parkland trees, the starlings that slept in the old warehouses by the river and the pigeons that lived in his block and in the tower of All Saints church half a mile away.

The arrival in the city centre of a pair of peregrine falcons had caused some excitement. They had made their home on the sheltered southern side of the roof of a redundant church that stood between his block and All Saints. The parent birds were raising offspring, and he had watched as the male picked off pigeons in mid-air on their perilous journey from All Saints' tower to the railway station roof.

He felt a keen affinity with the peregrines, while in his imagination the hapless pigeons were the members of the settled world, the gorgios, slow-moving and sluggish-witted.

Members of the settled world surrounded folk like him with as many laws and petty regulations as they could. They tried to shackle the gypsy traveller because they couldn't tame him. So the traveller had no choice but to seize his chances or succumb to the pressure to conform. He had decided long ago that he was never going to give in.

Luke listened to the Scotsman's voice on the other end of the phone telling him how hard life was these days and how resourceful a dealer in "quality merchandise" had to be merely to stay alive. There was nothing in Tam's spiel he hadn't heard before. It was Tam's long-winded way of softening him up for some favour or risky project from which they would both make enough money to put their feet up for six months "in Scarborough or Skegness."

As far as Luke knew, the antiques dealer had never been to either town. But Tam, like every born hustler, could never stop working, not for six months or even six hours. Luke imagined the man even dreamed of cutting deals in his sleep.

It was true he had made a lot of money with Tam, most of which he had used to buy pasture land that he rented out to other gypsy travellers for rough grazing. He had even bought a small hill farm in the Welsh Marches, where his own horses were cared for by an extended family of traveller craftsmen who had rent-free use of the buildings.

But he had no interest in money for its own sake, and to cap it all, he had developed a growing dislike for the Scotsman. He had come to the conclusion that it was impossible to believe a word the dealer said, even to someone like himself, who had known him for over a decade. When Tam got around to asking about his state of health, he was ready with his own stock reply.

"Me? Not good, mush. This kind o' work's getting too dodgy. Last time, if you care to recall, I almost got nicked… I know there'll be a moon, but I ain't up for it tonight… You want to find a younger guy to do this sort o' work."

While Tam continued persuading, Luke reached on to a shelf for a can of beer. He put the phone on the window ledge and took a long swig. He almost choked.

"How much?… You're taking the piss, mush—there ain't such a figure! We gonna be nicking an old master? You know some Chinese billionaire buyers now, right?"

He took another swig of beer as Tam continued his sales talk. Eventually, as usual, Luke's curiosity got the better of him.

"Okay, I'll come down. But no promises! I don't care if it's an easy climb or not. You give me something tonight, mush, if it's gonna pay so much… 20K in advance, right? Make damn sure you've got it! You will? Okay, see you later."

He rang off, drank his beer and stared from the window. He shouldn't have agreed. Tam McBride was trouble. He was taking bigger and bigger risks—or, truth be told, the cunning dealer was expecting that he would take the risks for him. And Tam knew too many dangerous people who could brush a poor burglar aside like a flea on a fox's ear if things went wrong. But where the dealer was concerned, there was always a challenge to be faced and a stack of money to be made. Maybe he'd be able to sign off on that derelict North Pennine hill farm only forty miles from Appleby…

3

An hour later, after he had been out to his favourite diner for a big fry-up and a mug of tea, Luke began to organize himself for the night to come. He took items from the shelves and laid them out on his bed in reverse order of requirement: packing straw, soft cloths, lock pickers, a small torch, flat-bladed knives, a small screwdriver, a coiled nylon rope, a balaclava and a pair of supple leather gloves. He checked the items thoroughly, almost reverentially. His life might depend on some of them.

He put on a light showerproof zip-up jacket with elasticated cuffs, then rehearsed swinging his frameless rucksack on to his back with a ten-kilo weight inside and snapping the waistband strap closed. The movement required perfect balance. He couldn't risk damage to items in the rucksack, but he might have to leave in a hurry.

With great care, he placed his gear in the rucksack, the small items in the side pockets and the rest in the body of the bag. Finally he took a pair of surgical gloves, folded one inside the other, then put them in his inside jacket pocket. He checked to make sure he had not forgotten anything—then, clad in the perfect disguise of hard hat and overalls, left by the rusting fire escape. A workman checking the state of the building was not likely to arouse much curiosity.

By six o'clock he was driving his old Renault Estate through an area of darkened yards and warehouses in a rundown industrial sector by a disused railway siding. He could hear the constant wail of police sirens through his open driver's window. They filled him, as always, with a toxic mix of dread and detestation.

Most of the businesses on the industrial estate had either moved or gone bust in the recession, giving the area the appearance of an abandoned wasteland. He pulled up outside Tam's yard and stared at the fancy carved sign above the double gates:

T McBRIDE

ANTIQUES DEALER & FURNITURE RESTORER

The sign was no more than a front. Very little dealing and no restoration work at all had ever occurred in the place. It was like the whole of Tam's life—a facade, behind which lay a world of trickery and deception. He wondered what would be left in the dealer’s character when all the subterfuge had been removed. Nothing perhaps. Silence. A black hole.

Luke sat a moment, beset by fresh doubts. He had the disconcerting feeling that it would be a very long time before he came that way again, if ever. Would he be caught tonight for the first time and get five years in jail? Would he be killed? But his curiosity got the better of him again. He took out his mobile and stared at it as if it was an unexploded bomb, then he tapped in Tam's number and announced his presence.

The gates opened remotely, and Luke drove into the yard. He pulled past a range of disused outbuildings and stopped by a shabby door marked OFFICE. The place looked even more derelict than the last time he visited, designed to support Tam's claim, should the Revenue guys start pressuring him, that he had given up the antiques trade and was getting used to retirement.

Nothing much had changed in Tam's office, either. There was a scattering of the usual antiques dotted about—odd items of porcelain, glassware, bronzes and silver—that gave the impression of a film set that could be packed up and disappeared in minutes. Anything of real value was kept elsewhere, in a location known only to the cunning dealer himself.

Tam, at fifty-five, was a thickset, tough-looking Scot with a mass of greying curly hair and florid features. He sat at his desk, a stack of out-of-date invoices at his elbow, held down by a damaged pseudo-Greek bust.

“Spring Heeled Luke,” Tam grinned, "my lucky charm! Glad ye could find time to drop by.”

Something wasn't right, Luke could sense it. He was picking up a bad vibe. "Ain't gonna be lucky tonight, Tam. Bad omens—gavvers everywhere."

"The po-liss, eh?" Tam emphasised the first syllable. His grin slipped slyly sideways. "And who, I'm wondering, would they be after?" He fixed Luke with a questioning glance.

Luke was used to the Scotsman's attempts at unsettling humour. But he was not going to be fazed. "Dunno, Tam. Some tricky dealer like you mebbe."

The Scotsman laughed. "That's more like it. If ye canna conjure a joke, ye's unfit for purpose." He watched Luke pacing restlessly around the room. "It's the past that's vexing ye still, is it, laddie?" The Scotsman fashioned a look of feigned sympathy.

Luke shrugged. "What if it is?" But it wasn't the past that was unsettling him. It was more like a premonition. Was he losing his nerve, or was he developing second sight? But now Tam had mentioned it, images of the lying police officer Nigel Hirst rushed into his mind. Hirst with his sneers and his talk of "filthy gyppos."

Tam poured his companion a mug of coffee. "Whisht. Clear your head. Ye canna live wi' ghaists at your elbow."

For a moment Tam seemed to be genuinely sympathetic. How much did he know of the past, Luke wondered? Did he know who had started the trailer fire? Did he know why?But he was aware if he asked him the slippery Scot would insult him with denials.

He sat on the only other chair in the room and drank the offered coffee. He disliked the stuff, preferring tea like most gypsy travellers, but decided to avoid further friction. He needed to relax, or the task ahead of him might prove to be his last.

Tam's Volvo Estate moved slowly through the quiet suburban streets of a small county town forty miles to the north of London. Could be anywhere, Luke thought. Anonymous dormitory England.

His restlessness and anxiety had left him at last. He could no longer hear police sirens, which always reminded him of the tragedy in his life and its unsatisfactory conclusion. He felt calm, his innate curiosity beginning to stir as he wondered about the shape of the night that lay ahead of him.

"What's so special about this job?" He didn't expect an entirely honest reply.

Tam smiled. "I was hoping ye'd get round to showing an interest. We're paying a call on a rich ex-con. He's a top guy. Speciality's antique smuggling. Likes to get hold o' stuff that's still rare. Guess it makes him feel special. Some call him eccentric. Others just say he's a twisted sense o' humour. By common consent he's a bit of a psycho. Lives on his own. Hates people."

"Sounds like you."

The Scotsman laughed. "That's the spirit, laddie! Takes one to know one!"

"What's he got?"

Tam was grinning widely now. "Treasures, my friend! Vases. Seal stones. Bronzes. Jewellery. Stuff from Egypt. A load o' loot from museums in Iraq." He paused for dramatic effect. "But they're not what we're after now."

Luke was intrigued. He realized Tam had him well and truly hooked. "What then? I can't get a Turner landscape into my backpack!"

"Whisht! We're after Ming ch'i, laddie. Spirit objects—embodiments o' spirit."

"You sound like a goddamn sales catalogue!"

Tam elaborated. "T'ang tomb figures to me and ye. He's a cabinet full. But we just want the horses."

"Why the horses?" Luke asked in puzzlement.

"My client believes in 'em. He's a horsey guy. He thinks they'll bring him good luck."

"He's a superstitious fella."

"Guess he is."

"He got a name?"

Tam shook his head. "Just ye bother about the horses, laddie!"

That subject was evidently closed. "So what's the deal?"

"C.O.D. And that's up to ye."

"I need an advance. And that's down to you!"

Tam feigned exasperation. "Whisht, laddie! Ye'll be paid."

"Ten percent tonight, Tam. We agreed. How do I know I'll see another penny? I'm taking the risk here, y'know!"

"Dinna fret. Ye'll be able to retire to Skeggy on this. Trust me."

"Stuff Skeggy! You should've got a career as a stand-up!"

They drove on in silence for five minutes. Luke's mind was focused, and he needed answers.

"What's the get-in?"

Tam turned the Volvo on to a leafy minor road. "Gable end wall. On'y bit that isna watched. Ye've done harder."

"One guy? Only one? You sure?"

Tam showed signs of impatience. Luke was unable to tell if they were genuine or for effect.

"Give me some credit, laddie! The guy sleeps alone in the first floor back. Not even a paid-for escort. He has his London associates round but only at weekends. Most rooms are unused."

Luke's mind flooded with doubt. "How d'you know all this?"

"I ken the body who installed the security."

"How come? A long way out o' your field, ain't it?"

"I bought his gambling debts. Small stuff really. But now, unofficially, he works for me."

That was as much as Luke could get out of the Scotsman. He would have to be content or call it off.

The Volvo entered a village main street. Expensive properties, a few newly built but most older, lined both sides of the road. All were in darkness. The car clock showed 1.45 a.m. Tam drove more slowly, checking his mirrors, glancing keenly out of the windows. Luke leaned forward, attentive.

"I've changed my mind, Tam. There'll be cameras everywhere round here. Every brick's a gold bar! It's too much risk."

"Risk?" Tam exclaimed. "What about me? I'm a businessman!" His tone softened. "Don't ye worry, laddie, our guy has no cameras on the end wall, on'y front and back."

The Volvo pulled into a field lane and stopped in the cover of trees. Its headlights were doused. As if synchronized, the full moon slid free from a bank of cumulus.

Tam pointed to a large detached property that stood at the far side of a small paddock. "That's the one."

A minute later, Luke's shadowy figure left the car.

4

Luke crossed the paddock, vaulted a post-and-rail fence, then found himself in the large back garden of the old three-storey brick-built manor house. From experience he guessed the building's date at around 1700-1710. He could see in the moonlight that the property stood in extensive grounds, with lawns, ranges of outbuildings and borders filled with low-maintenance shrubs. Wide gravel paths led around to the front of the house. As he drew closer, he could see that the place had a double-pitched roof.

Following Tam's advice, he moved away from the back of the house where there were supposed to be surveillance cameras, although he was unable for the life of him to spot any. He supposed he must be too far back to see them, but he began to wonder if the Scotsman had been economical with the truth. Looking at the layout of the property, the logical place for cameras was on the northwest and southwest corners of the house, covering the back, front and western gable end wall. The eastern end of the house was attached to a range of outbuildings and was too exposed to be approached. He was wary of cameras. They were the one and only cause of his unfortunate police reputation.

He came closer, crouching among the bushes and studying the gable end wall in the moonlight. The wall itself was in shadow, a problem only for gorgios with no night vision. But it was obvious now that there were no motion-sensitive lights and no cameras fixed to the house walls. How the hell was the property protected? He cursed Tam under his breath. What else had the slippery Scot lied about? He began to have serious misgivings about the entire business, but the lure of large profit kept him focused. When he was paid for the heist, he would spend a few days exploring the potential of that hill farm.

First he had to decide if the climb was possible. After five minutes' examination, he decided there was only one route, and even that might prove too difficult. Damn that greedy oat-brained Scot! He had every right to back out, telling Tam the wall was unclimbable.

But, as so often before, a part of him refused to give in. It wasn't that he had a reputation to uphold, because very few people actually knew he was involved in this line of work—it was all supposition—and the few who did know kept the knowledge to themselves, not wanting to lose a man with such skills to punters with deeper pockets.

It was a personal thing. He was proud that he could achieve climbs that had defeated the best cat burglars. Occasionally he'd had to resort to rock-climbers' gear, but mostly his free-climbing skills relied solely on speed, strength and agility.

This was going to be one of those climbs. Tightening the rucksack waistband, he began to work his way up the wall via drainpipes and window architecture. He found a few good finger holds where loose mortar had come adrift and scratched out a couple more with the small screwdriver hooked to his jacket collar. He could have saved himself the forty-foot climb by breaking what he assumed was a small bathroom window on the first floor, but he resisted the temptation. The window would almost certainly be wired.

He could have used a grappling hook. But he had learned from past experience that the higher you climbed the more unreliable the brickwork became on a property of this age. If it gave way, all you could do was go down. He had only fallen three times in the last ten years, but each time he had managed, parkour-style, to roll through the fall upon landing, saving himself broken limbs and a terminated career.

As he reached the gully between the double-pitches of the roof, he lost his grip on a loose, unmortared coping stone and had to hang by one hand for a half minute while he shifted his weight so he could grab a rainwater hopper to save himself. He'd had these moments before, and his pulse hardly registered the danger. Then he was into the gully, getting his breath back and refocusing.

His distrust of grappling hooks was confirmed. The brickwork at the western end of the gully was seriously frost-damaged and would have given way under his weight. He opened his rucksack, removed the rope and left it neatly coiled in the gully, ready for his escape. He would loop it behind the bracket that secured the hopper and pull it through when he reached the ground.

He knew there would be some means of access from the house to the gully, and sure enough, there was a wood-and-felt dormer-type trapdoor at the far end. He inserted a flat-bladed knife between the door and its surrounding framework, relieved to find there were no locks. With firm downward movements, he freed the two wooden catches that held the woodwork in place, and the trapdoor swung inwards on its hinges with no more than a brief squeak. He put on his leather gloves and balaclava, then vanished through the door into the house.

He was in a large attic, set out like a workshop for repairing damaged furniture. The room reeked of lacquers, varnishes and glue. Obviously the rich ex-con liked to indulge in practical activities. He crossed to the next attic room and peered out of a window. The front garden lay below: a wide moonlit terrace with urns leading to a lawn and a shrubbery. He left the room and descended a flight of stairs to the first-floor landing. Moonlight streamed in through a large uncurtained window. The doors from the landing were all open except one. He listened at the closed door… Silence.

A ground-floor rear reception room was his target. He found the room shuttered, the air stale and lifeless. It was merely a place for the owner to gloat over his illegally acquired possessions. He located two large cabinets: one contained figurines and seal stones from Iraqi museums; the other held the T'ang figurines.

With his torch between his teeth and wearing the surgical gloves, he quickly picked the cabinet's lock. He removed soft cloths from his rucksack, took the four horse figurines Tam had described to him, wrapped them in the cloths and packed them carefully in the straw inside the rucksack.

As he moved to the door, he spotted an infrared security light winking in a recess. He froze, shocked.

"Damn you, Tam, you lying Scots fishbrain!" he cursed the dealer under his breath.

Then he tightened the waistband on his rucksack and hurried from the room.

He stepped warily into the moonlit hallway. Before he could reach the stairs to the first floor, he felt the cold steel of a double-barrelled shotgun pressed to the back of his neck.

The infrared had done for him. He stood absolutely still, every faculty stretched to its limit. He heard the distinctive rhyming slang of an East End voice behind him. The voice seemed filled with amusement.