1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 0,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

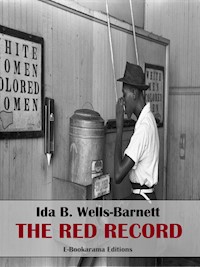

In "The Red Record," Ida B. Wells-Barnett presents a groundbreaking exposé illuminating the rampant injustices of lynching in America at the turn of the 20th century. This meticulously researched work intertwines persuasive rhetoric with poignant anecdotes, demonstrating the pervasive racism that plagued the United States post-Emancipation. Through a combination of statistical analysis and personal narratives, Wells-Barnett exposes the systemic social and racial violence inflicted upon African Americans, particularly against Black men accused of crimes against white individuals. Her literary style fuses journalistic rigor with a passionate call for action, situating this book not only as a historical document but also as a manifesto against racial violence. Ida B. Wells-Barnett, a prominent journalist and civil rights advocate, was profoundly influenced by her experiences as an African American woman in a racially charged society. Her tireless efforts in the suffrage movement and her activism against racial injustice were indicative of her commitment to social reform. Wells-Barnett's profound personal encounters with the brutal realities of lynching propelled her to raise awareness and mobilize public sentiment through this vital work, establishing her as a leading voice in the campaign for justice. "The Red Record" is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand the historical context of racial violence in America and the roots of systemic racism that persist today. Its compelling narrative and thorough documentation not only shed light on the past but also resonate deeply with contemporary struggles for justice and equality. Wells-Barnett's brave confrontation of these issues establishes this work as a pivotal text in both American history and feminist literature. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - An Author Biography reveals milestones in the author's life, illuminating the personal insights behind the text. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Red Record

Table of Contents

Introduction

A ledger of blood becomes a map of a nation’s conscience. The Red Record confronts readers with an unadorned accounting of lynching in the United States, forcing a reckoning with the distance between American ideals and American realities. By assembling facts rather than theatrics, Ida B. Wells-Barnett transforms statistics into testimony and numbers into a moral argument. The book’s power begins in the premise that truth, made visible, can challenge denial. In its pages, patterns emerge that puncture myths, expose complicity, and demand accountability. The work insists that what is counted cannot be ignored, and what is named must be faced.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, journalist and civil rights advocate, published The Red Record in 1895. The book compiles and analyzes reports of lynching, organizing them into a systematic overview that reveals the scope and character of racial terror. It pursues a clear purpose: to document, to refute falsehoods, and to rally public sentiment toward justice. Wells-Barnett relies on publicly available information and contemporary press accounts, but her method is neither passive nor neutral; it is investigative. She arranges data to expose patterns, tests alleged causes against the evidence, and invites readers to measure national claims of law and order against observable facts.

Written in the wake of Reconstruction and amid the consolidation of Jim Crow, The Red Record addresses an era when extrajudicial violence sought to police the boundaries of citizenship and power. Wells-Barnett recognizes that sensational accusations often preceded mob violence and that the press could amplify, rather than interrogate, those narratives. Her counter is meticulous aggregation: she places reported incidents side by side, enabling readers to discern repetition, motive, and pretext. This method grants the book a dual character—as historical record and argument—allowing it to stand as both archive and indictment. Its careful scrutiny makes evasion difficult and accountability possible.

The Red Record is considered a classic because it fused moral clarity with empirical rigor at a time when both were urgently needed. It expanded the possibilities of American prose by demonstrating how data, presented plainly, can carry a profound ethical charge. The book helped establish a tradition of documentary activism, influencing how later writers and organizers would marshal evidence to confront injustice. Its endurance in literary history rests on craft as much as courage: the text’s structure, pacing, and restraint model a rhetoric of precision. In an age of spectacle, Wells-Barnett proved the lasting power of sober truth.

The book’s influence reaches far beyond its immediate moment. It provided a template for anti-lynching campaigns that invoked statistics to demand legal reform and international attention. Journalists and scholars have cited its approach as a forerunner of data-driven reporting and social research. Activists learned from its insistence that changing the narrative requires both documentation and dissemination. The Red Record stands alongside foundational works in African American letters, not only for its searing subject but for its methodological innovation. Its legacy can be traced in the ways subsequent generations gather evidence, contextualize violence, and insist that public memory include uncomfortable facts.

Wells-Barnett’s style is precise, formal, and deliberately unsensational. She refuses the lurid details that once fed public appetite for spectacle, choosing instead the steadiness of tables, summaries, and analysis. That restraint heightens the book’s moral force: by declining melodrama, she leaves no refuge in claims of passion or confusion. The composition moves between enumeration and commentary, allowing data to set the frame and argument to illuminate meaning. Through this structure, the book cultivates a readerly discipline—witnessing through attention, judgment through evidence. The result is prose that is both archival and urgent, a record that speaks in the cadence of proof.

Essential facts anchor this work. The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States appeared in 1895 and built upon Wells-Barnett’s earlier investigations, extending the time span and depth of her documentation. It compiles reported incidents, notes the stated justifications, and tests those claims against patterns that emerge across cases. The author’s intention is explicit: to confront a national crisis by making its contours indisputable. Without resorting to speculation, she traces how rumor hardened into rationale and how violence functioned as social control. The book thus becomes both a mirror of the period and a tool for change.

At its ethical core, The Red Record insists that counting is a form of recognition. By enumerating victims and cataloging circumstances, Wells-Barnett restores individuality where mobs sought anonymity and erasure. She scrutinizes the so-called causes of lynching, showing how allegations—presented as public safety—obscured reprisals, economic rivalries, and political intimidation. The text underscores responsibilities neglected by institutions charged with upholding law. It also emphasizes the power of citizens to challenge false narratives through evidence. In assembling a public record, the book assigns readers a role: to witness, to remember, and to insist that justice be measured by facts, not fear.

The themes are uncompromising: truth against rumor, law against mob violence, citizenship against exclusion, and memory against oblivion. The Red Record invites readers to consider how a society’s credibility hinges on the treatment of its most vulnerable members. It exposes the fractures between constitutional promises and lived realities, and it explores the corrosive effects of impunity on civic life. The book also reflects on the press as both a shaper of perception and a site of contestation. In linking data to conscience, it frames justice as an empirical endeavor and moral obligation, where evidence becomes a vocabulary for dignity.

The book’s classic status endures because it offers a model for interdisciplinary engagement. Historians read it as primary source, journalists as early investigative reporting, sociologists as pattern analysis, and students of literature as exemplary argumentative prose. Its economy of style, tight organization, and explicit purpose make it a touchstone for courses on American studies, African American history, and ethics. Writers studying advocacy learn from its balance of restraint and resolve. That versatility has kept The Red Record in classrooms and public conversations, not as relic but as reference. Its pages continue to teach how to see, how to assess, and how to respond.

For contemporary audiences navigating information overload and contested truths, The Red Record feels strikingly present. Its insistence on verifiable facts, transparent sources, and clear reasoning anticipates modern debates about data, misinformation, and accountability. Readers encounter a text that refuses to sensationalize suffering while refusing, just as firmly, to minimize it. The book encourages evidence-based activism and patient, principled scrutiny—habits as necessary today as in 1895. Engaging with it sharpens critical reading, deepens historical awareness, and cultivates civic courage. It shows how rigorous documentation can puncture convenient myths and how moral imagination can be disciplined by proof.

Ultimately, The Red Record endures because it marries method to conscience. It transforms public reports into an argument for the sanctity of law, the dignity of human life, and the responsibilities of citizenship. In its pages, readers encounter themes of truth-telling, accountability, resistance, and remembrance—qualities that resonate across generations. The work remains engaging not only for what it reveals about the past, but for the habits of mind it models: precision, clarity, and integrity. To read it is to join a long conversation about justice in America and to recognize that facing facts is a form of hope.

Synopsis

The Red Record, published by Ida B. Wells-Barnett in 1895, is a documentary account of lynching in the United States. Building on her earlier investigation Southern Horrors, it compiles statistics, newspaper extracts, and brief case notes to quantify the practice and examine the alleged causes given by mobs. The book sets out to replace vague assertions with tabulated data, organized by year, race, state, and accusation. Wells frames the study as a factual ledger covering 1892, 1893, and 1894, preceded by historical background and followed by analysis. The narrative proceeds methodically, keeping close to verifiable reports as the basis for its principal findings.

After a short introduction, the book surveys conditions before emancipation to establish a baseline for comparison. In this antebellum record, social control over enslaved people was enforced through plantation discipline and the courts, rather than organized mob killings justified as popular justice. Wells notes that claims about protecting white womanhood did not function as a routine rationale for extralegal violence during slavery. By sketching this background, the text underscores a change in both the language and methods of punishment after the Civil War. The section anchors later statistics in a longer history of racial hierarchy, labor control, and public punishment.

Next, the narrative moves through the postwar and Reconstruction years, when political conflict and vigilante activity expanded. Wells describes how the withdrawal of federal protections and the contest over Black citizenship created opportunities for mob rule. Early instances of collective violence are tied to efforts to suppress voting, reorganize labor, and reassert local authority. Over time, the stated motives shift: political accusations give way to criminal allegations, with rape and murder invoked most prominently. This transition sets the stage for the book’s core chapters, where annual records are presented to test whether the often-repeated justifications match the documented causes of lynchings.

The account then turns to 1892, presented as a peak year in the period studied. Drawing on press tallies and independent compilations, Wells provides the number of persons lynched, disaggregated by race and state, and classified by alleged offense. The tables show that accusations ranged from murder and rape to theft, assault, “race prejudice,” and even no specific charge. She enumerates incidents in both rural and urban settings and records cases where victims were burned or mutilated. The summary emphasizes patterns: most victims were Black, the practice was concentrated in the South but not confined to it, and many charges were minor or unproven.

The 1893 chapter updates the ledger, noting changes in totals and distribution while maintaining the same method. Wells outlines where lynchings increased or declined, which states recorded the highest numbers, and how the mix of alleged offenses shifted. She documents continued reliance on the “unwritten law” of mob action and cites instances where entire communities assembled to witness executions. The narrative flags cases resulting from accusations other than rape, including disputes over wages, self-defense, or alleged insolence. By preserving the same categories as the prior year, the book enables comparison of proportions and trends across offenses, locations, and racial designations.

In reviewing 1894, Wells completes the three-year record and adds aggregate tables across the period. She summarizes totals for each category of allegation and compares them with the rhetoric that lynching primarily punishes sexual assault. The compiled figures show that while rape is regularly cited, a substantial share of victims were accused of other crimes or of no offense at all. The section highlights recurring features: arrests preempted by mobs, prisoners taken from jails, and punishments carried out without trial. By placing three years side by side, the book underscores continuity in methods and disproportions in the stated causes versus recorded actions.

Having established the statistics, the book examines the alleged causes in detail, especially the rape charge. Wells collects cases in which investigations, later reports, or community knowledge indicated consensual relationships or false accusations. She also notes episodes where economic success, business rivalries, or labor disputes preceded a mob killing, suggesting noncriminal motives under the surface. Instances of collective punishment against families and the lynching of women are included to demonstrate the breadth of targets. The analysis emphasizes that mobs often act before evidence is gathered, substituting rumor for inquiry, and that the category labels in newspapers can obscure complex local circumstances.

Wells then addresses how law enforcement, courts, and the press shape outcomes. She records sheriffs overpowered by crowds, juries declining to indict, and governors refusing to intervene. Newspaper coverage is shown amplifying accusations while minimizing retractions, thereby reinforcing the legitimacy of mob action. Descriptions of torture, burning, and dismemberment document the public nature of many lynchings and the participation of official and unofficial spectators. This section argues that impunity rests on public sentiment and political calculation as much as on private malice. The cumulative effect is to show a system in which legal processes are displaced by spectacle and collective coercion.

In conclusion, The Red Record calls for recognition that lynching is a form of lawlessness incompatible with constitutional guarantees. Wells urges reliance on due process, impartial investigation, and the punishment of those who organize or assist mobs. She appeals to national, state, and local authorities to enforce existing laws, and to citizens and the press to challenge false narratives and sensational claims. The overall message is that careful documentation can rebut myths, mobilize public conscience, and support reform. By turning scattered reports into a coherent ledger, the book aims to make accountability possible and to chart a path away from extrajudicial violence.

Historical Context

The Red Record appeared in 1895 amid the violent unmaking of Reconstruction’s promises. Its empirical survey spans the United States, with emphasis on the postbellum South—Tennessee, Mississippi, Georgia, Texas, and Louisiana—where extrajudicial killings had become systemic tools of racial control. The temporal focus centers on 1892 to 1894, years of conspicuous lynching spikes that Wells-Barnett documented from newspaper tallies. Memphis, Tennessee, is especially pivotal: a booming river city where Black entrepreneurship met white backlash. Chicago, where Wells relocated after 1892, provided a comparatively safer base and a major press platform. The book’s setting thus straddles southern sites of violence and northern arenas of advocacy and publication.

The wider national landscape was defined by rapid industrial growth, railroad expansion, and the consolidation of Jim Crow systems. Federal retreat from Reconstruction, the rise of Redeemer politics, and court decisions limiting civil rights set the legal and political stage. Simultaneously, the Black press, mutual aid societies, and churches constituted resilient institutions that Wells frequented for sources and allies. Lynching functioned as public spectacle, political warning, and economic disciplining, often unimpeded by local authorities. By assembling names, places, alleged offenses, and methods, Wells situated the book within a geographic and social matrix that linked courthouse squares, jailhouses, newspapers, and mob activity across the South and into national discourse.

Reconstruction (1865–1877) reshaped citizenship with the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, briefly opening pathways to political participation for formerly enslaved people. Federal occupation and the Freedmen’s Bureau offered limited but real protections. Yet violent resistance—organized through groups like the Ku Klux Klan—contested these gains. By the mid-1870s, federal will weakened. The Red Record reflects the aftermath of this collapse: its pages track how rights formalized in the 1860s were nullified in daily life by the 1880s and 1890s. Wells’s statistics and case narratives demonstrate how the promise of equal protection devolved into a regime where extrajudicial punishment replaced law for Black Americans.

The Compromise of 1877, which resolved the contested Hayes-Tilden election, effectively ended federal occupation in the South and empowered Redeemer governments. Earlier tactics like the Mississippi Plan (1875) had already shown how intimidation and fraud could suppress Black voting. Paramilitary organizations—the Red Shirts in the Carolinas, the White League in Louisiana—normalized political violence. With Reconstruction dismantled, states reasserted control over labor and race relations. The Red Record links this political settlement to the emergence of lynch law as governance by terror. Wells’s accounts of county sheriffs ceding prisoners to mobs and local juries refusing indictments trace their lineage to the post-1877 restoration of white supremacist rule.

In 1883, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Civil Rights Cases invalidated key provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, ruling that the Fourteenth Amendment constrained only state action, not private discrimination. This decision greenlit segregated accommodations and emboldened businesses to exclude Black patrons. It also signaled a narrowed federal role in civil rights. The Red Record documents how this judicial retreat translated into lived vulnerability: when mobs seized prisoners from jails, local authorities often framed it as community action outside state responsibility. Wells’s methodical juxtaposition of legal precedent and unchecked mob violence underscores how constitutional rights were undermined by a judiciary disinclined to protect them.

A wave of disfranchisement swept the South beginning with Mississippi’s 1890 constitutional convention, whose poll taxes, literacy tests, and understanding clauses became a template. South Carolina (1895), Louisiana (1898), North Carolina (1900), and Alabama (1901) adopted similar mechanisms. These measures eliminated Black voters and many poor whites, consolidating one-party rule. The Red Record, published amid this transformation, shows how political exclusion and lynching reinforced each other: without the ballot, Black communities lacked leverage over sheriffs, prosecutors, and juries. Wells repeatedly notes that lynchings clustered where officials were electorally insulated from Black constituencies, illustrating the interdependence of racial terror and disfranchisement.

Between the 1880s and mid-1890s, lynching became a routine instrument of control. Newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune, kept annual tallies from 1882 onward, recording hundreds of cases nationwide with concentrations in Georgia, Mississippi, Texas, and Louisiana. Accusations ranged from murder to alleged sexual assault, theft, or violations of racial etiquette. The Red Record interrogates these categories, classifying alleged offenses and exposing how minor disputes or economic competition often led to killings. By reprinting names, dates, and locations, Wells counters the anonymity and rumor that mobs exploited. Her data-driven format transformed local atrocities into a national ledger, challenging apathy by converting spectacle into evidence.

The postwar economy bound Black labor to landowners through sharecropping and the crop-lien system, while convict leasing transferred incarcerated labor to private companies in states like Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee. These systems created incentives to overpolice Black communities and criminalize debt. Economic friction—over wages, rents, or market competition—could escalate into racial violence. The Red Record repeatedly identifies business rivalry and labor disputes beneath sensational pretexts. By disentangling economic causes from moralized accusations, Wells shows how lynching protected local monopolies and enforced labor subordination. Her case discussions make plain that lynch law buttressed a political economy of cotton, timber, and railroads rather than merely punishing crime.

The Panic of 1893 unleashed bank failures, business collapses, and mass unemployment. National unrest was visible in Coxey’s Army (1894) and numerous strikes. Economic panic intensified scapegoating across the South, where mobs redirected anxieties onto Black communities. Contemporary newspaper tallies recorded elevated lynching numbers in the early 1890s. The Red Record places the spike within this downturn, arguing that economic stress magnified the use of racial terror to discipline labor and suppress competition. Wells cites year-by-year data to show patterns in timing and geography, demonstrating that lynching frequency rose with economic volatility and partisan campaigns, rather than merely tracking criminal incidents.

The 1892 lynching of Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and William Stewart in Memphis was the catalytic event for Wells’s campaign. The three co-owned People’s Grocery, a thriving Black cooperative in the Curve neighborhood, which challenged a white competitor, William Barrett. After a tense confrontation on March 5, 1892, police arrested Black defenders. On March 9, a mob abducted Moss, McDowell, and Stewart from the Shelby County jail and murdered them near the rail yards. Moss, a postal worker and Wells’s friend, reportedly urged migration as he lay dying. The Red Record takes this episode as emblematic: economic success, not alleged crime, prompted the violence.

Wells responded in the Memphis Free Speech with editorials condemning the murders and urging boycotts and migration, causing thousands to leave Memphis. In May 1892 she argued that consensual interracial relationships were commonly miscast as rape to justify lynching. While she was in New York, a white mob destroyed her newspaper office on May 27, threatening to kill her if she returned. This exile propelled her to national platforms and intensified her reliance on documentary evidence. The Red Record builds upon these editorials, formalizing her argument that the rape pretext was a myth wielded to police intimacy, suppress economic competition, and intimidate a politically rising Black populace.

From 1893 to 1894, Wells toured Britain, speaking in London, Birmingham, and Edinburgh with reformers such as Florence Balgarnie and Quaker networks. British audiences formed anti-lynching committees and pressed American diplomats, generating transatlantic scrutiny. Meanwhile, the Chicago Inter Ocean and other northern papers printed her investigative pieces. In The Red Record, she consolidates materials from these campaigns, combining Tribune tallies with case studies and affidavits. She categorizes alleged offenses, distinguishes rumor from corroboration, and contrasts mob claims with court evidence when available. This methodological rigor—honed abroad and in Chicago—gave the book a statistical backbone and international resonance that local pro-lynching editorials could not easily dismiss.

The World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893) celebrated national progress while excluding most Black exhibits. Wells, with Frederick Douglass, I. Garland Penn, and Ferdinand L. Barnett, issued the pamphlet The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition, distributing it on the fairgrounds. The pamphlet documented disfranchisement, segregation, and lynching. The Red Record extends this expositional strategy by grounding moral indictment in empirical documentation. Wells’s experience contesting the fair’s narrative of civilization sharpened her insistence that statistical truth could pierce civic self-congratulation, positioning the book as a counter-exhibit to the era’s triumphant public rituals.

Plessy v. Ferguson arose from Homer Plessy’s 1892 challenge to Louisiana’s Separate Car Act; in 1896 the Supreme Court upheld separate but equal. Although The Red Record preceded the final decision, it appeared amid the legal consolidation of segregation. Plessy’s logic—that separation could be neutral—helped normalize a racial order in which police, courts, and legislators colluded with mobs by denying equal protection. Wells’s tabulation of lynchings undercuts Plessy’s fiction of neutrality: the book shows that segregation’s social ecosystem enabled lethal violence with impunity. Her data-driven critique anticipated the jurisprudential consequences that would soon be codified nationwide.