8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

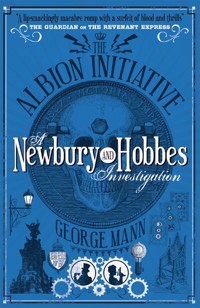

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

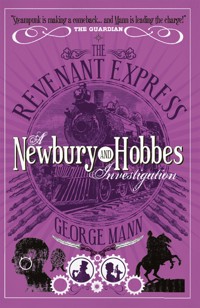

- Serie: Newbury and Hobbes

- Sprache: Englisch

Sir Maurice Newbury is bereft as his trusty assistant Veronica Hobbes lies dying with a wounded heart. Newbury and Veronica's sister Amelia must take a sleeper train across Europe to St. Petersburg to claim a clockwork heart that Newbury has commissioned from Fabergé to save Veronica from a life trapped in limbo. No sooner do they take off then sinister goings-on start to plague the train, and it is discovered that a mysterious cultist is also on board, determined to recover a precious artefact. Can Newbury and Amelia defeat him before he carries out his terrible revenge? But as Newbury and Amelia hurtle towards the only thing that can save Veronica, they uncover a terrible secret that could threaten the lives of everyone on board. A secret linked to Veronica's past…

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 355

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

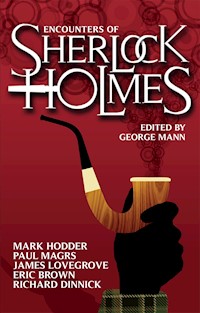

Also by George Mann and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Acknowledgments

Read on for Another Newbury and Hobbes Short Story

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

Newbury and HobbesThe Casebook of Newbury and HobbesThe Affinity BridgeThe Osiris RitualThe Immorality EngineThe Executioner’s HeartThe Revenant Express

The GhostGhosts of ManhattanGhosts of WarGhosts of KarnakGhosts of Empire

WychwoodWychwoodHallowdene

Sherlock Holmes: The Will of the DeadSherlock Holmes: The Spirit BoxEncounters of Sherlock HolmesFurther Encounters of Sherlock HolmesAssociates of Sherlock HolmesFurther Associates of Sherlock Holmes

Print edition ISBN: 9781781160060E-book edition ISBN: 9781781166451

Published byTitan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark StreetLondonSE1 0UP

First edition: February 20192 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2019 George Mann. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Some days, she liked the rain.

As a child she had often sought its purifying qualities, enjoyed the play of it upon her upturned face. Out in the garden of her parents’ home, heady with the scent of damp, fresh earth, she had allowed it to wash away all concerns; for her desperately unwell sister, her bickering parents, her ailing grandmother. She had not forgotten the comfort of those days, and even now, she still enjoyed the thrill of being caught in a sudden English downpour.

Today, however, was not one of those days. Today she would have rather been at home, curled up by the fire, or else in her barely used office beneath the British Museum, shuffling papers; anywhere but in Stoke Newington in a torrential downpour, standing amidst a gaggle of police constables and overeager civilians who had yet to be persuaded to clear the area.

Veronica angled her umbrella in order to look for Sir Charles Bainbridge, sending a cascade of pooled water over the brim, spattering her shoes. She sighed.

Bainbridge was standing a few feet away, muttering in low, fractious tones to another man she didn’t recognise. When he saw her looking, he gave a weak smile and raised a hand in brief salute. He looked hassled, which, Veronica allowed, was quite understandable, given the circumstances. All of the furore, all of the noise and bluster and milling crowds, centred around the thing on the pavement, the object that she had so far studiously managed to avoid. The people around her had already dubbed it—in hushed, scandalised tones—“the monster.” She could ignore it no longer. Bracing herself, she turned her head to regard it.

She stifled a gasp. It was even worse than she’d imagined. The creature was, without doubt, one of the most ghastly things she had ever seen.

It had once been a human being—although she couldn’t easily ascertain whether a male or female—but now its body was so bloated and malformed as to be almost beyond recognition. The victim appeared to be on its back, its belly distended to at least three or four times its natural capacity. The flesh had burst, and from deep within the intestines strange plant-like growths had erupted, pushing out through the ruins of the person’s clothes.

Tendrils, resembling masses of thick, ropey vines, were splayed across the pavement, spilling out from the corpse as if feeling their way towards the gutter. Pink tumours, resembling bulbous, fungal growths, nestled amongst the vines like sickly blooms, ready to burst open at any moment and dissipate their spores.

The flesh of the face was terribly misshapen, as if the same gnarly growths had formed beneath the skin, bulging out, warping the features into something less than human. The result was that the victim looked as if it had suffered from a severe case of elephantiasis, or that the corpse had been preserved mid-metamorphosis, frozen in a state of change. Perhaps most bizarrely, fresh green shoots had emerged from the fingertips of the right hand, which rested on the paving slabs nearest to Veronica, as if the dead person were reaching out to her in silent desperation.

She swallowed, feeling bile rise in her gullet.

Two constables were holding umbrellas above the remains, attempting to protect it from the storm, but despite their best efforts, raindrops were still bursting upon the creature’s hide, trickling over the exposed flesh and giving it a glistening, glossy appearance. While she watched, a man in a white smock nudged one of the constables out of the way and began poking around in the corpse’s mouth with his index finger.

Veronica shuddered.

“Horrible, isn’t it?” muttered someone nearby. The voice was familiar. She adjusted her umbrella and turned to see Inspector Foulkes standing just a few feet away, regarding the corpse with a thoroughly disgusted look on his face. He turned his head, his expression brightening slightly when he saw she was looking. He was a tall, bearded man in his late thirties, a good policeman who, in recent months, had begun to appear rather downtrodden by the interminable horror of his profession.

“It is, rather,” she confirmed.

They were silent for a moment.

“How are you, Inspector? Is your family well?” she asked, in an effort to dispel the pall of gloom that had seemingly settled over them. Neither of them, however, could tear their eyes from the sight of the unusual corpse.

“Oh, very well indeed, Miss Hobbes. And your sis—” He caught himself mechanically reflecting her question. “That is, I mean to say…” He looked pained. “Oh, I’m sorry, Miss Hobbes. Things must have been very difficult for you, since your sister passed, and I… I…” He trailed off, unable to find the right words.

Veronica smiled. “Why don’t you step out of the rain for a moment, Inspector? This umbrella’s big enough for two.”

Foulkes sighed with barely concealed relief. “Thank you, Miss Hobbes,” he said, with feeling. He edged closer and she held the umbrella aloft to accommodate him. As a result, she felt the patter of raindrops against the back of her plush red evening cloak. The garment, she knew, would never be the same again.

Foulkes blew into his cupped hands and tried, unsuccessfully, to wipe the dripping water from his eyes with his damp sleeve.

“What is it?” she asked, nodding in the direction of the body. “What’s happened here? I’ve never seen anything like it.”

“Nobody seems to have any idea. It’s as if his body has been infested with these growths, plants that appear to have germinated in his guts,” Foulkes said.

“A parasite?” asked Veronica.

Foulkes shrugged. “Perhaps. I think Sir Charles is hoping that you and Sir Maurice are going to help to answer that particular question.”

“Hmmm,” said Veronica, as noncommittally as she could. She looked up to see Bainbridge concluding his conversation with the man he’d been talking to.

He stalked over to join them. “Foulkes, get rid of these people,” he said, waving a hand at the crowd. “Close both ends of the lane until we know what we’re dealing with.”

“Very good, sir,” replied Foulkes. He glanced at Veronica with a look so forlorn that she had to stifle a laugh. He looked like a drowned, moping puppy. Sighing heavily, he stomped off to speak with one of the uniformed constables.

“It’s good to see you, Miss Hobbes,” said Bainbridge, taking her by the hand. He seemed distracted. “Where’s Newbury?” he asked, peering over her shoulder. The lapels of his heavy woollen overcoat looked sodden, and rain was spraying from the brim of his bowler hat. Droplets had settled in his grey-speckled moustache. He seemed beyond the point of caring.

Veronica sighed. “Otherwise engaged,” she replied. She tried to keep the disappointment from her voice.

Bainbridge frowned, his shoulders sagging. “Oh, don’t tell me we’re back to that? We’re not going to have to drag him out of one of those despicable Chinese smoking dens again, are we?”

Veronica shook her head. “No. Not that. He’s gone north. He received word that Lady Arkwell had been operating out of a small mining town near Durham, and took off at once. That was two days ago.”

“Oh, perfect,” snapped Bainbridge, leaning heavily on his cane. “Stuck in the rain with a… a… well, I don’t know what it is, and Newbury’s nowhere to be seen.” His moustache twitched in frustration. “This Arkwell woman is becoming another of his ruddy obsessions.”

“Hmmm,” murmured Veronica, by way of agreement. She fought back a sharp stab of jealously, cursing herself for such petty emotions.

Newbury had, indeed, become rather obsessed with his pursuit of the female agent in recent weeks, and Veronica had seen very little of him, save for the brief episodes during which he attended to her sister’s health at Malbury Cross. He’d taken to turning down many of the cases that would otherwise have captured his interest, and now, he was absent even when his oldest friend, Sir Charles Bainbridge, was in need of his help.

“What the Devil are we going to do now?” barked Bainbridge in consternation. He was being somewhat unreasonable, expecting Newbury to be available at his beck and call, but all the same, Veronica knew it was derived from concern for his friend, and for his investigation, rather than any real sense of entitlement.

Veronica put a hand on his arm. “I’ll do my very best to assist in any way I can, Sir Charles,” she said, pointedly.

Bainbridge’s eyes widened as the nature of his unintended slight suddenly dawned on him. “Oh, quite so, Miss Hobbes. Quite so.” He gave a forced smile. “And most welcome such help will be.”

Veronica bit her tongue. “So,” she said breezily, despite the sinking feeling in the pit of her stomach, “what would Sir Maurice do?”

Bainbridge’s face creased in an unexpected grin. “Other than drop to his knees in that filthy puddle, poke the corpse with the end of his pen, and utter ominous and obtuse noises, you mean?”

Veronica laughed. “Other than that, yes.”

“Well, for a start, I believe he’d be interested in whatever Dr. Finnegan here has got to say,” replied Bainbridge, taking her gently by the elbow and leading her over to where the man in the white smock was still hunched over the corpse, poking about in its mouth with his ink-stained fingers. He didn’t look up or appear to acknowledge their presence.

Veronica gave the man a brief appraisal. He was in his middle to late fifties, with wild, wispy grey hair that clung to his balding pate in thin cusps. He wore thin, wire-framed spectacles on the end of his nose, and was reviewing the body with something approaching glee. He was wearing his cotton smock—once white but now stained with patches of faded brown, which Veronica recognised as spilt blood—over a loose-fitting brown suit. His left trouser pocket bulged dramatically, as if he were harbouring something alive inside of it.

“Why’s his pocket… well, moving like that?” whispered Veronica, leaning closer to Bainbridge in order to be heard over the sounds of the storm. He smelled of damp cloth and lavender.

“Ah. That’ll be his ferret,” replied Bainbridge, apparently nonplussed.

“His ferret!” remarked Veronica, unable to contain her bemusement. “Here, at a crime scene?”

“A potential crime scene,” replied Bainbridge. “We’re unsure what happened, yet.” He shrugged. “Finnegan’s an eccentric old blighter, but he does a solid job. He’s one of our best surgeons. Newbury’s fond of him.”

“Hmmm,” said Veronica, grinning. “That explains a lot.”

“Guinea Golds,” announced Finnegan, suddenly, stepping back from the body and arching his back, his hands on his hips. He sighed heavily, and flexed his neck from side to side. He spoke with a clipped Irish brogue.

“I’m sorry?” said Veronica.

“No need,” said Finnegan, shaking his head. “It’s not your fault the poor beggar had a fondness for cigarettes, now, is it?” He peered at her over the top of his rain-spattered spectacles and offered her a wide, gap-toothed grin. What was left of his hair was now plastered to the side of his head with rain, but he seemed not to notice. “Or is it?”

“It’s most definitely not,” said Bainbridge, interjecting. “Dr. Finnegan, this is Miss Veronica Hobbes. She’s assisting with my enquiries.”

“Delighted to meet you, my dear,” said Finnegan, thrusting out his hand.

Veronica glanced at the corpse, then back at the hand. She took it gingerly. “A pleasure to meet you, Dr. Finnegan,” she said.

“Owen, my dear. Owen. I insist!” He retracted his hand and rubbed emphatically at his temples, as if trying to encourage his brain. He swatted at a sudden burst of movement from his pocket, frowning at the unwanted distraction. “Not now, Barnabas. Can’t you see I’m busy?” The pale brown head of a ferret popped out momentarily from the pocket, glanced around nervously with little beady eyes, and then ducked back inside.

Veronica gave a polite cough. “So, tell me, Dr. Finnegan—Owen—have you any idea what it is, yet?”

Finnegan nodded enthusiastically. “Why, it’s a corpse, my dear,” he said, by way of reply.

“We can ruddy well see that!” said Bainbridge, impatiently. “What can you tell us?”

Finnegan offered him a fierce, quizzical glare.

“About the body, I mean!” clarified Bainbridge, the exasperation evident in his tone.

Finnegan gave a brief nod. “It’s a man, in his late twenties, I’d estimate. He was once a heavy smoker, and seriously malnourished. He carries an old wound to his left shoulder. He’s been infected with the revenant plague for some time—” At this Veronica took an involuntary step back, and Finnegan watched her, appraisingly. “But curiously the infection has not run its full course,” he continued. “His damaged flesh appears to have been healing.”

“Healing?” echoed Bainbridge, astonished.

“Yes, it’s really quite remarkable,” replied Finnegan. “His body seems to be rejecting the plague.”

“Like Sir Maurice,” said Veronica. “He’s somehow established a tolerance for the infection, through previous exposure. Immunity, if you will.”

Finnegan shook his head. “No, not immunity. This poor sod had already succumbed to the plague. It’s more that he appears to have been making steps towards recovery. Look here.” He prodded the dead man by the left ear, easing back a ragged flap of torn skin. “The necrotic flesh has peeled away, but there’s fresh, pink growth forming underneath.”

“This is unprecedented,” said Bainbridge. “Is it related to all of this bizarre flora?” He waved the end of his cane to indicate the eruption of vegetation emanating from the dead man’s belly.

Finnegan wavered for a moment. “I don’t know. It may be entirely unrelated, or it may be that whatever species of plant infected him had a bearing on the progression of the disease.” He removed his glasses, wiped them on the front of his already sodden smock, and replaced them. He frowned at the fact he still couldn’t see through the smeared lenses.

“Forgive me, Dr. Finnegan, but is it really possible for a plant to take root inside a person’s body?” asked Veronica. “It seems… somewhat unlikely.”

Finnegan nodded. “Yes, quite right, Miss Hobbes. Highly unlikely. I wouldn’t testify to it, but I have a theory that what we’re dealing with here is a microsporidia infestation.”

“A what?” blustered Bainbridge.

“A parasitic fungus,” explained Finnegan. “But I’ll have to take it back to the lab to confirm.”

“Well, you’d better get on with it, then,” said Bainbridge, shaking his head.

Finnegan turned and glanced over his shoulder, beckoning to two uniformed constables who were sheltering in a nearby doorway beside a wooden cart. Reluctantly, they stepped out into the downpour and slowly wheeled the cart over. Finnegan was just about to start issuing instructions when Veronica interjected with another question. “Just one more thing, Dr. Finnegan. This parasitic fungus—assuming that’s what it is—I take it it’s not native to the British Isles?”

Finnegan looked thoughtful. “No, I would imagine it originates in a more tropical climate,” he said. “Otherwise we’d have likely seen it before.”

“So, do you think there might be foul play at work?” Veronica pressed.

Finnegan shrugged. “Who’d want to murder a plague revenant?” he said. He turned and began conversing with the constables in low, precise tones.

“It’s a good point, Miss Hobbes,” said Bainbridge, from over her shoulder. “The poor fellow does seem the most unlikely of targets for a murder. Damned odd though, isn’t it?”

Veronica nodded, although she was watching the three men manhandle the bloated corpse onto the wooden cart in preparation for ferrying it away to Finnegan’s laboratory. “Something about it doesn’t sit right with me, Sir Charles. I can’t help thinking there’s more to it than meets the eye.”

“Perhaps you’re right,” said Bainbridge, in a conciliatory tone. “Finnegan will have more for us in the morning. Right now, I think we could both do with getting out of this damnable weather.”

Veronica turned to him, and smiled. “I can’t argue with that,” she said.

“Come on,” said Bainbridge, indicating the other end of the lane with the tip of his cane. “I have a police carriage waiting. I’ll drop you at home.”

“Thank you,” said Veronica, looping her arm through his as they negotiated the slick cobbles. “And tomorrow?”

Bainbridge laughed. “Tomorrow I shall send for you as soon as there’s word. We can question Finnegan together. If you’re still unsure after that—well, we’ll have to see.”

Behind them, Finnegan and the two constables trundled off into the downpour, bearing their unusual cargo along with them.

The rich tang of oil and smoke stung her nostrils as she shoved her way through the unyielding crowd. The people here, she decided, were not at all like those at home. Their continental attitudes were both heady and enticing, and scandalously obtuse.

In London, a woman would never be left to drag her own case across the platform, but here at the Gare du Nord, everyone was so engrossed in their own noisy business—hurrying to be the first to board the train—that no one stopped to pay her even the slightest modicum of attention as she hauled the leather trunk across the concourse.

Not that she minded, particularly. It was quite exhilarating not to be patronised. She simply wished they’d get out of her way in order for her to pass.

Amelia searched the platform for Newbury. She couldn’t see him amongst the bustle of people and the billowing steam that issued in hissing jets from the immense, shuddering engine. It was a remarkable feat of engineering: at least twice the size of the typical, domestic steam engines she’d seen back home in England, with sleek golden skirts and fat, snaking pipes of gleaming brass. Hastily erected scaffolds had been pushed against the sides of the vehicle, and men in blue overalls clambered over the tank and engine housing, wiping streaks of soot and sweat from their shining red faces as they prepared the machine for the first leg of its tremendous journey across the continent.

Behind the engine stretched the train itself, two stories high and so long that its tail disappeared somewhere beyond the far end of the platform. Already, passengers were milling about inside the carriages, haggling over compartments and fighting to be the first to the best seats. Thankfully, Newbury had reserved them a first class suite on the lower level of the train, close to the front, so she wasn’t going to have to join in with any of the distasteful bickering.

Nevertheless, she couldn’t help but feel a slight pang of apprehension at the thought of such a long journey, and, perhaps more pointedly, to such a far-flung destination. She’d heard tales of St. Petersburg, of an icy fantasia filled with frost-rimmed palaces, wondrous clockwork machines and magical creatures, and the very thought of it left her feeling breathless and excited all at once. Not to mention a little guilty, given the cause of their mission. She had to keep reminding herself that she was not there for her own gratification. More than anything, she wanted to help her sister.

“Remarkable, isn’t it?” said a familiar voice, startling her from her reverie. She turned to see Newbury standing at her shoulder, regarding the train with a tired, weary expression. He looked handsome in his top hat and black suit, although there were dark rings beneath his eyes, and more lines than she had noticed before. Amelia knew that his concern for Veronica, along with the ongoing impact of her own treatment, was taking its toll on him. He’d lost weight, and where once he had appeared fit and lean, he now seemed painfully thin. He’d already told her that he was having trouble sleeping.

“Confirm to me again, Sir Maurice, that this journey is absolutely necessary,” she said.

Newbury looked over, his expression firm. He put his hand on her arm, gripping it intently, and she wondered for a moment if he wasn’t clinging onto her as much for his benefit as hers. “Amelia, it is entirely necessary. If we are to help Veronica then we must undertake this journey. Only the artisans of St. Petersburg can provide us with the intricate mechanisms we need to replace your sister’s heart.” Amelia nodded. “And besides,” continued Newbury, “if I am to make such a journey, you understand that you must accompany me. It is the only way we can continue with your treatment. We will be gone for some time.”

“Very well,” said Amelia, forcing a smile. “Then we must continue as planned.”

“I’ve booked us adjoining cabins,” said Newbury, “that open into a shared living room. We should be comfortable.” He smiled. “Come on, let’s try to settle in while our fellow travellers board.” He gestured to a nearby porter and the man, sweating profusely, obligingly took Amelia’s luggage and swung it up onto his trolley. Muttering under his breath, he struggled across the platform towards the train, trundling their bags behind him.

Amelia looped her arm through Newbury’s and they followed behind, pausing as the porter checked their tickets for the carriage number, and then started off again, full of bluster, in the opposite direction. Amelia suppressed a chuckle at the look of consternation on the man’s face.

“As unenviable a job as I could imagine,” said Newbury.

“Really?” countered Amelia. “I can’t think the firemen would agree, shuffling all of that coal, hour after hour, in such infernal heat.” Up ahead, the engine issued a hissing gush of steam, as if to emphasise her point. A small huddle of women, clutching their hats as if they expected to lose them in the sudden gust, stepped back in surprise.

“Ah, but at least they’re warm,” said Newbury, with a grin. “And besides, they don’t have to deal with all of these people.”

Amelia shook her head, laughing. Newbury was being as contrary as ever; while he clearly enjoyed his solitude, she knew he couldn’t bear to be without the bustle and attention of other people for too long. In this regard, at least, he wasn’t so different from everyone else. She, on the other hand, was finding the whole experience rather invigorating, after spending so long cooped up indoors in Malbury Cross, pretending to be dead. It felt good to be out in the world again.

“Ah, here we are,” said Newbury, leading her over to where the porter had parked his trolley on the platform and was—rather indelicately—unloading their bags, tossing them up onto the train through an open door. She felt Newbury tense as he watched his leather suitcase slide across the floor on its side.

Up close, the vehicle was even more impressive than it had seemed from across the platform. The lustre of the green paint had not yet been dulled by the weather, and the carriage gleamed in the thin morning light. It towered above her, its two stories reaching a good twenty feet above the platform.

They were to board here, it seemed, in order to locate their rooms: the third carriage in line behind the engine’s tender, close to the very front of the train. Amelia leaned to one side to enable her to peer over the porter’s shoulder. Through the windows she caught glimpses of plush interiors and fittings that gave the impression of a sumptuous gentleman’s club, rather than a passenger train. It looked most inviting.

All around her, people were clamouring to board; a woman in a mink coat barked commands at another porter to hurry along with her oversized case; a young couple slipped aboard carrying their own bags, paying little attention to whatever else was going on around them; a tall man with a bushy grey moustache and a military bearing was mustering two small boys, who whispered conspiratorially to one another in hasty French.

All of it seemed so new to Amelia, and must have seemed so mundane to Newbury, she thought, who had seen so much of the world. Veronica, too, had travelled widely and seen wonders in all corners of the globe. This journey, then, this small, new experience, felt to Amelia like something of a triumph, as if she were finally leaving her old life behind and starting out again, with something new.

“Come along, then,” said Newbury, taking her arm. “Let’s take a look at where we’ll be staying.”

Amelia nodded and allowed him to guide her up the steps.

The vestibule was not at all what she had been expecting, even after peering through the windows at the grandeur of the cabins on either side. It resembled the hallway of a large London house, only somewhat smaller and more contained, with a chequerboard marble floor, a spiral staircase encircled with impressive wrought iron railings, tall potted plants, and portraits of stately looking people she didn’t recognise. To her left, a passageway led away into the carriage, and this is the direction in which their porter had disappeared, dragging their bags behind him. She followed, single file behind Newbury in the confined space.

“This is it,” said Newbury a moment later. “Suite seventeen.” He indicated the open door, and Amelia peered in.

The suite comprised three interlinked rooms—two small cabins that adjoined a larger, but still modest, drawing room. Additionally, each room had a door that opened directly onto the passageway, which ran the entire length of the carriage, from the lobby area where they’d boarded to, presumably, the vestibule that linked them to the next coach in the train. There would be at least one other suite of rooms on this lower level of the carriage, she guessed; the length and appearance from the outside suggested as much.

Above them, on the upper floor, would be the social areas—the observation lounge and the like. She’d read about them in the literature that Newbury had given her as they’d journeyed south from London to Dover. She would explore those later, she decided, once they’d settled in and were properly underway.

The porter had finally finished unloading their bags, placing them just inside the door, and Newbury saw him off with a small coin. Amelia watched the man clatter away with his trolley, still muttering beneath his breath.

She stepped over the threshold, taking in the room in which she would be spending the majority of the coming days. Behind her, Newbury closed the door and turned the key in the lock.

The drawing room was well appointed, with three armchairs arranged around a small card table, a hat stand, an aspidistra in a large terra-cotta pot, a gilt-framed mirror upon the wall, and a window, presently covered by a fine net curtain, that looked out upon the station. The floorboards underfoot were polished and worn. It was cosy and clean, and more than she’d expected. Indeed, it was larger and more comfortable than many of the hospital cells in which she’d spent her formative years.

“Yours is the cabin on the left,” said Newbury, with a wave of his hand. “I hope it’s comfortable. I know it’s not much,” he sounded apologetic, “but it’ll be home for a while. We’ll make the most of it.”

Amelia smiled. “It’s just fine,” she said. She crossed to the door he’d indicated. When she opened it, the hinges creaked in tortured protest. She winced, supposing the likelihood of having them oiled was probably nonexistent. She’d just have to hope that Newbury didn’t object if she needed to get up in the night.

The cabin was compact but well appointed, with a bunk, a luggage rack, a small closet, an external-facing window, and the other narrow door, leading out to the carriage beyond. The room was panelled in dark mahogany, adding to the sense that the place had been designed to resemble the interior of a gentleman’s club or country estate, and had a clean but slightly musty smell about it. The sheets on the bed looked crisp, white, and functional.

She sensed Newbury behind her. “I hope it’ll suffice,” he said.

“It’s small, but cosy,” she said, with a smile. “And far more than I’ve grown used to, over the years. It’ll seem like a luxury.”

“Well, I wouldn’t go that far,” said Newbury, laughing. He edged past her, approaching the door to the passageway. He slid the bolts. “Keep this door locked,” he said, running his hands around the frame as if searching for any possible weaknesses in the structure. “Bolted from the inside. Use the door to my cabin as our only entrance and exit from the suite.”

Amelia frowned. He seemed suddenly direct, serious. “Yes, if you insist. But why?”

“It’s safer that way,” he replied, a little dismissively. He’d already crossed to the window and was methodically examining the frame. “Keep this locked, too.”

Amelia sighed. “Very well,” she agreed, “although it all seems rather unnecessary.”

Newbury turned to her. Again, that determined look: the fixed jaw, the firmness in the set of his mouth, the cold eyes. This was a side of him she’d never seen, and she wasn’t much sure she liked it, or at least, what it represented. This, she presumed, was the professional Newbury, the experienced agent—the man who had faced all manner of terrible things and somehow managed to remain alive. Perhaps some of those experiences had left him suffering from a touch of paranoia? No one could experience such horrors and remain undamaged.

“Trust me, Amelia,” he said. “It’s entirely necessary.” There was something about his tone that caused her to shudder: the fact his voice was so calm, level. This wasn’t a man in the grip of irrational fear. This was an experienced agent securing a room because he anticipated a threat.

“Is there something you haven’t told me?” she asked, and she could hear the slight break in her voice. She’d been right to hesitate earlier on the platform, she realised. This wasn’t going to be a holiday, an adventure. She was journeying into the unknown, and it was evidently fraught with danger.

Newbury shook his head. He offered her an attempt at a reassuring smile, but it was too late for that—the seeds of doubt had already begun to take root in her mind. “I fear, Amelia, that trouble has a tendency to follow me around.”

“But you suspect danger?” she pressed. “You think there’s someone on this train who means us harm?”

Newbury crossed to her and placed his hand gently on her upper arm. “Not specifically, no. I’m not aware of anyone on this train who might mean me ill, but neither am I prepared to take chances. Nor do we know any of the other passengers, their reasons for being aboard the train, or even whether they’re travelling under assumed identities. Do you think they suspect your real name is not ‘Constance Markham,’ for instance?” He paused, and then continued, more softly. “In my line of work, Amelia, one has a habit of making enemies. Experience has shown me that it pays to be prepared, to expect them to strike at any moment. That way we won’t be caught unaware. If the trip proves uneventful—well, what have we lost?” He paused for a moment to let the question sink in. “I didn’t mean to frighten you.”

“But that’s no way to live, always looking over your shoulder,” she countered. “And besides, I’ve never seen you like this. You don’t take precautions like these when we’re in London, or Malbury Cross.” She was careful to keep any note of accusation from her voice, but he was correct to be contrite—he had scared her.

“You’re right. Of course, you’re right. It’s just that London is my home, you see. It’s familiar. It’s home turf. If anyone tries to catch me out, well, at least I know what I’m about, where to go and from whom to seek help. Out here,” he waved his hand about him to indicate the cabin and the wider world beyond, “out here we’re on our own. Everything hinges on our mission, you see. Everything. And so we must take the necessary precautions.” He looked her in the eye. “Do you understand?”

Amelia wanted to say no, that she didn’t understand, didn’t even want to understand. She could have no part in this horrible business of suspecting everyone else on the train of malign intent. Yet, despite all of that, she felt herself nodding. She had to trust Newbury’s experience, and she knew his intentions were sound, whatever his methods: to help Veronica, no matter what. He was right in that, at least. They couldn’t allow anything to get in the way of retrieving Veronica’s new heart. “Yes, very well,” she said. “I understand. I’ll do as you ask. Although I’m damned if I’m going to conduct myself in a manner that treats everyone I meet as a suspect.”

“I would never expect that of you, Amelia,” said Newbury. “You’re far too considerate for that.”

She chose to take his comment as a compliment, despite the fact she knew what he really meant was that he considered her gravely naïve. In contrast, she couldn’t help thinking how desperately sad it was that Newbury should feel this way. It must be a terrible thing to find oneself unable to trust other people, to always look for the worst in everyone. Perhaps, she decided, this was her role for the duration of their trip—to help cure Newbury of this deep-seated paranoia, to show him there were still good people in the world. Despite everything, despite what had happened to Veronica, she believed that wholeheartedly, and she would prove it to Newbury, too.

The carriage jolted suddenly beneath her, and Newbury, smiling, reached out and caught her elbow, steadying her as she lurched to one side. “It seems we’re on our way,” he said.

Her response was drowned out by the screech of a shrill whistle from the platform, the scrape of wheels against the iron track, and the increasingly feverish chugging of the engine as they pulled away from the station.

Amelia sighed. Their journey into the unknown had begun—in more ways than one.

If this was to be his lot in life, then Clarence Himes had absolutely nothing to fear from eternal damnation in the afterlife.

All those years hearing talk of hellfire and brimstone on a Sunday morning, the vicar preaching that a life of sin and misdemeanour would lead to condemnation and torment in the next life—at no point had the young Clarence imagined the waking Hell he might first be forced to endure as a working adult. None of it had prepared him for this.

He slumped against the door frame, mopping his brow with the filthy sleeve of his overalls. It was unbearably hot, and the work was relentless, feeding the insatiable machine with enough fuel to keep the boiler going, to continue driving several tons of engine, carriage, passenger, and needless, ostentatious junk halfway around the world.

He blinked away the sweat running into his eyes. Not only was it hot, but the boiler room was dirty, confined, and stank. How had he ended up here, hurtling across France in a grimy sweatbox, all for the sake of a pittance?

And then there was the work itself—well, he knew there had to be consequences. What they were doing, it was just plain wrong, no matter which way you looked at it. Somehow, it was all going to come back to haunt him. He knew it, with the same sort of certainty and conviction that evangelical vicar had shown all those years ago.

From across the other side of the compartment Clarence’s comrade in arms, Henry Sitton, grinned at him inanely, his face under-lit by the bright amber glow of the furnace. Sitton’s eyes were lost in shadowy relief, and his smile seemed to take on something of a sinister aspect. “Nearly time for elevenses,” he said, patting the front of his overalls. “I’m near famished.”

Clarence made an appalled face. “I don’t know how you can eat anything in here, let alone cook it on a skillet over that.” He emphasised the last word with a wave of his hand toward the furnace. “It’s not right, Henry.”

Sitton grinned wolfishly, like a child enjoying the effect of his outrageous behaviour. “What harm can it do, eh? It’s just a couple of sausages and a few rashers of bacon. You need to keep your strength up on a journey like this. Mark my words, you’ll soon be wishing you’d listened to me. I’ve done this trip before, remember.” Sitton clapped his hands together, but the thick leather gloves he was wearing deadened the sound.

Clarence shook his head. “You can count me out,” he said, grimacing as he watched Sitton slide his gloves off and pull a shovel from the bucket beside the fire. He reached for the little parcel he’d stashed earlier in the cubbyhole where they stored their personal effects, and began hungrily unwrapping the waxy paper.

“I don’t see why you can’t just make up some sandwiches like everyone else,” said Clarence, watching, fascinated, as Sitton carefully arranged three rashers of bacon and two sausages on the filthy shovel. “You could eat them in your bunk, instead of in here, surrounded by all that.” He nodded at the heap of fuel in the corner, suppressing a shudder.

Sitton shrugged. “It burns just as well as anything else,” he said, nonchalantly. He wiped his hands on his overalls, smearing grease and soot, and then slid the shovel into the furnace. Almost immediately, the sausages began to hiss and spit.

Clarence decided he needed to change the subject. “So, if you’ve done this trip before, you’ve already been to St. Petersburg. Tell me, is it true what they say?”

Sitton laughed. “And what is it they say, Clarence?” He smirked ungraciously, as if amused by Clarence’s apparent naïveté.

Clarence felt his cheeks flush. “Well,” he said. “You know. There are stories. They say it’s not at all like London, that there are enormous palaces carved from the very ice itself, and frost-fingered sprites that come for your children in the night. That the city guard ride the streets on bears instead of horses, and that weird mechanical birds drift over the rooftops, spying on the people below.”

Sitton shrugged. “I wouldn’t know about any of that,” he said, “but you’re right on one count. It ain’t nothing like London, that’s for sure. Frigid cold and full of stinking foreigners.” He slid the shovel from the fire, examined the blackening stumps of his sausages, and returned it to the flames. “My advice to you, Clarence, is to do as I do and mind your own business. Stay on the train and keep your head down. It only takes them a day or so to turn everything around and replenish all the stocks for the journey home. Why risk venturing out? Even if it was true, I can’t imagine why you’d want to see it. The only thing you’ll find in a place like that is trouble, mark my words.”

Clarence nodded, as if acknowledging the sage advice of the other man, but his heart wasn’t in it. He’d keep his own counsel. He’d heard all manner of fascinating tales about St. Petersburg, with its frost-limned minarets, shimmering palaces, colourful bazaars, strange creatures, and even stranger people. He was damned if he was going to work his way halfway across the world only to sit in his tiny bunk and pass up the opportunity to take in the sights. A day wasn’t long, but it was something. It was his, and he would use it to explore. The thought of that day was the only thing keeping him going; the promise of a brief respite, and a break from the dreadful monotony of his labour.

Sitton was over by the furnace again, retrieving his makeshift meal. To Clarence, it looked decidedly burnt, but then he couldn’t even conceive of wanting to eat it. Not there, in that room, with that smell. Even the thought of it was enough to make his stomach heave.