Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

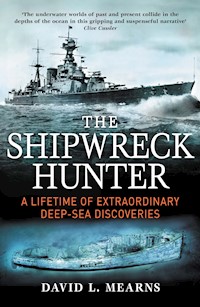

Winner of the Mountbatten Award for Best Book, 2018 David Mearns has discovered some of the world's most fascinating and elusive shipwrecks. From the mighty battlecruiser HMS Hood to the crumbling wooden skeletons of Vasco da Gama's 16th century fleet, David has searched for and found dozens of sunken vessels in every ocean of the world. The Shipwreck Hunter is an account of David's most intriguing and fascinating finds. It details both the meticulous research and the mid-ocean stamina and courage required to find a wreck miles beneath the sea, as well as the moving human stories that lie behind each of these oceanic tragedies. Combining the derring-do of Indiana Jones with the precision of a surgeon, in The Shipwreck Hunter David Mearns opens a porthole into the shadowy depths of the ocean.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 759

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Sarah, Samuel, Alexandra and Isabella

Dedicated to the survivors and the families who preserve the memories of those lost at sea

Contents

List of Illustrations

Prologue

Introduction

1 MV Lucona: MURDER AND FRAUD ON THE HIGH SEAS

2 MV Derbyshire: LOST WITHOUT TRACE

3 HMS Hood and KTB Bismarck: SEARCH FOR AN EPIC BATTLE

4 TSS Athenia: THE FIRST CASUALTY OF WORLD WAR II

5 HMAS Sydney (II) and HSK Kormoran: SOLVING AUSTRALIA’S GREATEST MARITIME MYSTERY

6 AHS Centaur: SUNK ON A MISSION OF MERCY

7 Esmeralda: VASCO DA GAMA’S SECOND ARMADA TO INDIA

8 USS Indianapolis and Endurance: WAITING TO BE FOUND

Afterword

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

Index

Picture Section

Copyright

List of Illustrations

Me (third from left) and my siblings Susan, Gina and Bobby in our back yard in Union City, New Jersey.

This green moray eel would attack me every day I worked on an artificial reef in St. Croix. As he refused to relocate to a nearby reef, my only choice was to be bitten or kill him.

Standing watch over the EG&G 259-4 side-scan sonar recorder during a survey in the Bahamas.

Udo Proksch surrounded by his staff at der Demel pastry shop in Vienna. Proksch gave the captain of Lucona one of Demel’s famous torte cakes, knowing that the bomb he loaded on board would kill the ship’s crew.

The crowded back deck of the Valiant Service. The ship was home for the Ocean Explorer 6000 and Magellan 725 systems for 15 months.

Lifting the Ocean Explorer off the deck prior to launch. I’m wearing a radio headset that allowed me to direct the crane and ship drivers during the launch.

Recovering the Ocean Explorer sonar in the Mediterranean Sea. The back deck was the most dangerous place to work on the Valiant Service.

This innocuous box, resting upside down, contained all the evidence to prove the ship we found was Lucona. Stencilled on its side was the codes (XB 19 and B10), manifest number (02354) and company name (ZAPATA SA) connecting the cargo to Udo Proksch.

The investigative journalist Hans Pretterebner managed to find this photograph of the actual cargo Udo Proksch had shipped in Lucona. It helped us identify the exact same pieces of machinery we found lying on the seabed in the debris field. Compare the object circled in both photographs.

The search for Derbyshire, and the DFA’s quest to learn the truth about her loss, frequently made front-page news in the UK.

Every bright yellowish target in this sonar image represents a piece of Derbyshire’s shattered hull.

This diagram shows the location of the controversial Frame 65 section of Derbyshire just forward of the bridge.

Mark Dickinson bravely backed ITF’s search for Derbyshire. He is now the General Secretary of Nautilus UK, the Maritime Officers’ union.

The plaque we laid on Derbyshire’s bow meant so much to the families it made me determined to do the same with Hood, Bismarck and Centaur.

At nearly 50,000 tons fully loaded, Bismarck (along with Tirpitz) was the biggest and most powerful warship ever built by the German Navy.

This picture of the open hatch door (U 145) through which Baron von Mullenheim-Rechberg escaped demonstrates the quality of pictures we could take at a depth of 4,900 metres.

Others have said that Bismarck’s armour belt was impenetrable. Here is visual proof that the British guns did put holes in the side of the German battleship.

The leather boots and jacket identify this as the remains of one of Bismarck’s engine room crew.

I wanted to lay the plaque commemorating Bismarck’s men on the bow, but I had to settle with placing it on the upturned Admiral’s Bridge as it took us so long to finally find the hull.

Hood’s wreckage, including the middle part of the hull, two debris fields and the conning tower (lower left sonar target) was scattered over a distance of 2.1 kilometres.

Greeting Ted Briggs with a bear hug when I finally got him safely on board our survey vessel over the wreck of his ship – HMS Hood.

Enjoying a toast and a cheeky whisky with Ted Briggs and other members of the production team after our successful mission to HMS Hood.

The bell of HMS Hood is now on permanent display in the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Portsmouth. When the Princess Royal rang the bell eight times to signify the change of watches, it was the first time the bell had been heard in seventy-five years.

The plaque that Ted Briggs laid on the anchor cable of HMS Hood. The gold CD contains the Roll of Honour of all 1,415 men lost in Hood.

A cartoon that appeared in Punch 10 days after Athenia was attacked by U-30, drawn by E.H. Shepard, who once lived in my village in West Sussex.

Karl Dönitz (right) with Fritz-Julius Lemp, Captain of U-30, in August 1940 after Lemp was awarded the Knights Cross.

One of the many child survivors from the SS Athenia being brought ashore in Galway, Ireland.

The twenty-two-year-old John F. Kennedy was sent by his father to meet the SS Athenia survivors that were brought into Glasgow.

It doesn’t look like much, but this multi-beam sonar image contained all the information I needed to know it was the wreck of Athenia.

Troops disembarking HMAS Sydney in Suda Bay, Crete in early November 1940. By this time Sydney had already earned multiple battle honours, which included sinking the Italian cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni.

The launch of Steiermark in Kiel on 15 September 1938. The ship was converted to the auxiliary cruiser Kormoran in early 1940.

Theodor Anton Detmers, Captain of HSK Kormoran. This photo was taken after the war as Detmers is wearing the Knights Cross he won for sinking the Sydney.

One of Sydney’s crew, Able Seaman Jack Davenport, with a ceremonial life ring.

Inside this German to English dictionary Captain Detmers hid his original ‘master’ account of the action with Sydney using tiny pencil dots under the letters. I have marked the relevant letters in red on the lower image.

I taped the picture of Sydney’s crew above my plotting table to give me, and everyone who passed by, extra motivation to find the wreck. This is where I was working when the wreck appeared on our sonar displays.

This shot of Sydney’s ‘B’ turret shows just how deadly effective Kormoran’s attack was. The single armour piercing 15cm shell through the front screen of the turret would have killed all 20+ men inside.

Virtually every surface of Sydney’s upper deck was peppered with shell holes from Kormoran’s guns.

Every watertight door on Sydney’s wreck was found in an open position, possibly indicating that the crew may have been trying to abandon ship at the last moment.

Sydney’s main director control tower lying upside down in the debris field. The heavy corrosion marks where the paint has been burnt off by fire.

Celebrating the location of Sydney with the directors of HMA3S, John Perryman (in white uniform) and the former premier of Western Australia, Alan Carpenter, fourth from left.

Sister Ellen Savage, the only nurse of the twelve on board Centaur to have survived.

With Chris Milligan in his McGill University office where for three days we trawled through all his valuable research documents.

At the end of many months of research I was left with a handful clues to where the wreck of Centaur might have sunk. Fortunately, Gordon Rippon’s navigation was spot-on.

Staring at this image of Centaur’s bell, my smile says it all. I couldn’t believe how truly lucky we were to have found the bell with its name showing.

If the bell of Centaur hadn’t ended up lodged between these two pipes it would have rolled off the deck and have been lost forever.

One of Captain George Murray’s leather shoes at the entrance to his bedroom.

The most remarkable discovery: an Australian Army slouch hat in the debris field next to the wreck of AHS Centaur where it had lain for 66 years.

One of the red crosses that marked Centaur as a hospital ship protected from attack by the Geneva Convention.

I was delighted to have received my Order of Australia Medal from the Governor-General Quentin Bryce at the Australia High Commissioner’s residence in London.

The only historical image depicting the loss of the Sodré brother’s ships. Note the name Esmeralda above the mast of Vicente’s ship.

A painting believed to be Vasco da Gama in the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in Lisbon.

Ahmed Al Siyabi of Oman’s Ministry of Heritage and Culture overlooking the beach where the Portuguese careened one of their ships to be repaired.

This disc I found has yet to be assessed by experts, but it has features that suggest it could be associated with an early type of astrolabe, an important and rare navigation instrument.

Esmeralda’s bell, after conservation and reconstruction. Dated 1498, this is almost certainly the oldest ship’s bell ever recovered anywhere in the world.

The legendary Indio, the lost or ghost coin of Dom Manuel I. The original silver of the coin has been replaced by silver corrosion products, which is why the coin appears black.

The heavy-cruiser USS Indianapolis. She had a hand in changing history but it was her men who paid the price.

Charles B. McVay III, the Captain of Indianapolis, who was unfairly court martialed for the loss of his ship.

Sir Ernest Shackleton – known to his men as ‘The Boss’. One hundred years on his example still inspires explorers of every type.

With Nick Lambert, former Captain of HMS Endurance, holding one of the ten Explorers Club flags I have carried on my expeditions.

In the Weddell Sea of Antarctica, where I hope to return one day to find and film Shackleton’s Endurance.

Prologue

For seven days the shipwreck, lost for fourteen years and lying broken somewhere on the abyssal plain over four kilometres beneath us, had eluded our new-fangled sonar: so brand new it was still on its first full operational dive. This was to be the last of nine search lines covering the 430 square nautical miles where we thought the best chance of the wreck being located was. If this line, like the eight we had already searched, was negative, we would be left with one simple question: was the shipwreck we were trying to find hidden within the mountainous terrain that occasionally cropped up throughout our search box, or were we simply looking in the wrong location?

I was doing my best to hide my uncertainty and inexperience from both my team and the clients, who were on board the small support vessel with us, but I could feel the pressure rising. It would make no difference to anyone that my company had performed amazingly well to design, build and mobilize in the ridiculously short period of five months all the specialist equipment we were using, or that the actual search operation had gone remarkably smoothly, without a second of lost time. Unless we found the wreck, our work would be deemed a failure. We had won this important and potentially lucrative search contract in the face of fierce competition from two far more experienced companies. When they vigorously protested the award and predicted that we would fail, in part because I personally was too inexperienced to lead such a challenging project, it put even more pressure on us to succeed.

Yet even the huge gamble my bosses had taken with the company’s future and reputation in tackling this complicated project paled in comparison with what was at stake for our clients. For them it was quite literally a matter of life and death. The life in question belonged to the man who was being criminally prosecuted for sinking the ship, while the deaths were those of the crew he was accused of callously causing. There are a number of reasons why someone might be compelled to spend several million dollars to find a shipwreck lost in the deep ocean. To solve a multiple murder case is arguably the most sensational.

I wasn’t sure what made me more nervous: that we still hadn’t found the wreck despite having nearly completed our search box; that having been appointed the expert witness for the search I would be held personally responsible should we fail; or that the trial judge was actually at sea with us monitoring every move and decision I was making. To make matters worse, I was getting on badly with the judge. We spoke different languages, and a dispute about how my company was being paid meant our relationship had been fraught with tension and distrust for the past several days. I wouldn’t have been surprised if he lost all faith in the search, and us, and terminated it when the current search line was finished.

At the extreme depth at which we were working, it took four seconds for the sonar’s acoustic wave, travelling at about 1,530 metres per second, to emanate sideways and scatter off mud, rocks and any man-made objects before returning to the sonar to be electronically converted into brightly coloured images displayed on the computer screens in front of us. At the end of each four-second cycle I would tilt my head closer to the screen to get a clearer look at the latest strip of sea floor revealed, hoping for the distinctive signs of wreckage to appear. After seven days, the constant tilting of my head forwards and backwards like the slow beat of a metronome was so ingrained in me it happened without conscious control. But while my body was stuck on autopilot, trapped in the tempo of the ongoing search, my mind was racing ahead with the possible repercussions of failure. As much as I hated admitting defeat – and I was careful to keep such negative thoughts to myself – I felt I had to be prepared in case the worst happened. And then the next four-second cycle changed everything.

Without warning, a bright yellowish-white rectangle appeared on my screen. The target was unlike any others we had seen during the search, mainly because it was sitting alone in the expanse of orangey-red that depicted the soft muddy sediment cover of the flat abyssal plain. In the time it took my heartbeat to accelerate, another ‘ping’ from the sonar illuminated what was undoubtedly a very hard object. Was it the start of a geological rock field, or just one of the countless pieces of marine trash that littered the seabed? Or would this target justify my quickening pulse?

A minute or two passed before I could sensibly assess what we were seeing. The images scrolled down the screen like a multicoloured waterfall, revealing what lay below as if the ocean had been magically drained of all its water. This god-like power was what had first attracted me to working with sonars. In my mind nothing could compare with the excitement of deciphering previously unexplored expanses of the sea floor like this. Radiologists could use X-rays and MRIs to peer into the body, but I could do pretty much the same with no less a subject than the earth itself.

Not long after the hard target appeared, it petered out and with it my hopes that we had found something significant. There were still a handful of faint yellow pixels scattered to either side, indicating that the target wasn’t a solitary object, but soon enough the seabed became as flat and featureless as before. By now, everyone in the twenty-foot container that served as our operations control centre was crowding my screen and weighing in with their opinions of what we had detected. My rough measurement of the target’s size showed it wasn’t even close to the 140-metre length and 18-metre breadth of the ship we were after. This wasn’t our shipwreck, but could it be a piece of it?

Our wreck had supposedly been sunk by a large bomb hidden in one of the two main cargo holds and timed to explode far away from any land mass, so we were expecting at least some of the hull to be blown to pieces. While it was disturbing to think of the shipwreck as a crime scene and the grave site of six innocent people, that was exactly what it was. All the available research indicated that no other modern ships had sunk in this area, but I also needed to recognize that our search box was situated along a major east–west shipping route, so the potential for unreported shipping losses to have occurred here was high. I believed I had designed a conservative search plan to give us the best possible chance of distinguishing our shipwreck from other targets, but after seven days of no results my initial confidence was seriously waning.

I waited in anticipation for more targets to follow the initial scattering, but none appeared. Slowly my head stopped its forward-and-back motion and began to drop. Was that it? A brief flutter of excitement and promise, followed by the empty feeling of failure? Was my career as a deep-ocean shipwreck hunter destined to start in disappointment, from which a second chance might never materialize?

Suddenly the screen began to glow brightly again with not one but a string of hard targets stretching across the starboard side of the line we were searching. Whatever the identity of these targets, their number and spread was about right for the dimensions of our shipwreck. This appeared to be the debris field of the exploded cargo hold section, but without a single large target representing the aft superstructure of the ship, there was no way to be positive. By now my face was just inches from the screen and I was praying for more targets. Finally my prayers were answered and one large beauty appeared.

I jumped up and felt a surge of exhilaration course through my body. ‘We’ve found it!’ I shouted. ‘That’s got to be our shipwreck! Look how it’s been blown to smithereens by the bomb!’ I threw both arms in the air and began to physically grab everyone in the container, although it was clear they weren’t as convinced by the images as I was. Quickly I started measuring the main targets to prove to them what I intuitively sensed: that the combined dimensions matched the ship very well. Whether they were persuaded or not, they all began to feed off my excitement.

Word began to filter through the ship that we had found something, and pretty soon our small container was heaving with people, including the judge and his three advisers. I repeated my explanations to the new arrivals, using zoomed-in views of the targets to reinforce my interpretations. Unlike photographs or video, sonar images are not visual, so they rely on experts to explain exactly what they represent. As I was one of only two people on board with any real experience interpreting such images, everyone had to more or less accept what I was telling them.

In truth, an additional higher-resolution sonar image of the wreckage would have to be produced to show that we had found the wreck, and even then only a photograph or video taken by an ROV would be acceptable in court as proof of the ship’s identity. I knew that the judge and his advisers would want a systematic investigation of the wreckage, and that several more weeks of hard work lay ahead, but now we would have all the time we needed to produce this evidence.

The search was not destined to end in failure as I had once feared. Instead it was to be a technical triumph and an enormous success for everyone involved. We had found one of the world’s deepest and most notorious shipwrecks, a wreck that was at the heart of an extremely high-profile murder trial with national importance in the country in which it was being held. We would no longer be viewed as novices amongst the small band of companies that operated in the deep ocean. We had proved that our equipment was superior and that our team was one of the best in the business. With this success under our belts, a string of clients would line up to hire our services and keep us in constant work for the next two years, thus transforming the value of our small company.

After all the excitement died down, I walked out to the fantail of the ship to have a moment to myself and appreciate what we had just achieved. I was elated by our success but also extremely relieved. Many months of hard, stressful work had paid off in the few minutes it took our sonar to reveal the shipwreck, leaving me with a feeling of satisfaction unlike any I had ever experienced before. If this was what it felt like to find a deep-ocean shipwreck, I was determined that it would not be the last time for me. In fact I was dead set on doing it again and again.

Introduction

‘How do I get a job like yours?’ Of all the questions I’m asked when I speak publicly about my work as a professional shipwreck hunter, this is the one I know will occur every single time. Invariably it comes from a young man, mid twenties at most, and by his tone of voice I can tell that he seriously thinks I might have advice that will change his life forever.

It’s a tough question to answer. For one, I never plotted out a path to this most unusual of professions myself, so I have no sure-fire strategy to offer. Secondly, I know of no school or university anywhere in the world that teaches all the skills needed to be a successful shipwreck hunter. Finally, and most importantly, there isn’t a ready-made industry out there looking to hire prospective shipwreck hunters.

My own story starts in Union City, New Jersey. Lost in the shadows of Manhattan’s skyscrapers across the Hudson River, Union City seems an unlikely location to inspire a future marine scientist. In fact its only claim to fame is that it is the most densely populated city in America, with nearly 60,000 people crammed into an area of just over one and a quarter square miles. To make matters worse, the nearest body of water is the Hackensack Reservoir Number Two, a man-made lake of 69 million gallons ringed by a two-metre-high fence to stop kids like me scaling it for a sneaky dip on a hot summer’s afternoon.

Not that New Jersey doesn’t have water; it is a coastal state with over 200 miles of seaboard fronting the Atlantic Ocean. But in the 1960s, when I was growing up, you hardly ventured beyond the three or four blocks that made up your immediate neighbourhood. When you weren’t in school, you were playing with your friends in the street between two long rows of parked cars. It might have been touch football, stickball, or skully – a game in which players shoot soda bottle caps along the road surface in between the passing cars – but whatever the game, it was generally within a few yards of your own front porch.

For lower-middle-class families like mine, holidays were a week or two each summer in a rented cottage down on the Jersey shore. These were great times with my brother and two sisters, when nearly every hour of the day was spent on the beach or in the water. We would body-surf on cheap Styrofoam boards until the skin on our chests was rubbed raw, or until our mother had to drag us home for dinner.

Occasionally a dorsal fin would be sighted just off the beach and the lifeguards would hurry everyone out of the water, but more often than not the offending beast was just a harmless sunfish. Sometimes, on a very clear day, a passing ship might be spotted steaming into Port Elizabeth to offload its cargo. Other than these moments, I would hardly ever think about what lay beyond the horizon or beneath the pounding surf. Despite my love of the ocean, these holidays weren’t the inspiration that drew me to a life working at sea.

Ironically, it was trips inland to my grandmother’s house in Honesdale in north-eastern Pennsylvania that were the real catalyst for my decision to study marine biology at university. As the youngest of four children, I would be packed off by myself on the bus to spend a week each summer visiting my cousins and uncles. Although Honesdale was barely a hundred miles away from Union City and could be reached by car in about two hours, it was the complete opposite of the city and like a whole new world for me. It was spacious, green, uncrowded and filled with lakes and ponds where I learned to fish and appreciate the natural beauty of the countryside.

My mother’s parents had emigrated to America from southern Italy around the turn of the twentieth century and eventually settled in Honesdale, where they had ten children, although two sadly died as infants during a diphtheria outbreak. They were a family of shopkeepers. First there was a general store and candy shop; later on, when my uncles were older and could help with the business, they ran a bar and restaurant that was widely known for making the best Neapolitan pizza in that part of Pennsylvania. The family was well respected within the tight-knit community, and when the call came to serve in World War II, three of my uncles fought on various fronts with the army and navy.

After the war ended, my two eldest uncles, Pete and Vince, together with some friends, bought 350 acres of private woodland to form the Bucks Cove Rod and Gun Club, where they could fish on several lakes and hunt for deer. Over the years, they bought additional land, nearly doubling the club in size, and added another lake, which they constructed themselves. These lakes were where my uncles taught me to fish for bass, catfish and the occasional toothy pike. We’d take a small rowing boat and stay out all day, releasing most of the fish we caught but keeping a few of the biggest catfish for supper. I loved those days with Pete and Vince. I never wanted them to end and would stay at the water’s edge deep into the night, casting my line to land one more fish, leaving only when the bats and the swarming mosquitoes forced me inside.

It never occurred to me then that something I loved doing so much could form the basis of a career, or that working in a natural outdoors environment was an option for me. My father was an antiques dealer who travelled in to Lower Manhattan every day to sell furniture to shops in Greenwich Village, while my mother was a registered school nurse looking after 1,200 students in a large city high school. Watching them go to work each day, I naturally assumed that I too would wind up working in a big city; probably Manhattan, where most people from across the river in New Jersey gravitated.

This mindset was forever changed, however, when I was sixteen and Vince took me to see a large freshwater fishery. I loved looking at the fish, of course, but mostly I was struck by the scientific approach that was used to produce the largest number of healthy fish possible. I remember leaving the fishery that day with the distinct idea that this was something I would enjoy and was capable of doing. When I came to think about what I would do after graduating from high school, I was torn between becoming an antiques dealer like my father and going on to university to study science. While I had become quite adept at the antique trade, having helped my father for many years, the people who inspired me the most were the astronomer Carl Sagan and the heart transplant surgeon Dr Christiaan Barnard. I found Sagan to be amazingly eloquent and passionate when speaking about the cosmos, while in my eyes Barnard was a bona-fide hero for being the first surgeon to successfully transplant a human heart.

My teachers had always marked me out as someone quite bright, but I wasn’t the best student because – in their words – I needed to apply myself more in class. Basically they all said I wasn’t working to my full potential. Not long after visiting the freshwater fishery, I went to the local library and began investigating careers that would allow me to work outdoors and ideally in conjunction with water and fish. I found information on becoming a fisheries biologist, which was immediately appealing, but the job that really fired my imagination was marine biology.

Marine biology ticked all the right boxes for me. It was a serious professional career in science that also offered the prospect of conducting research at sea on marine organisms including fish. Compared with being a freshwater fisheries biologist, which I thought might restrict me to jobs within the continental United States, the idea of being free to work on all the world’s oceans seemed limitless and exciting. There was also a very important practical matter.

One of the universities listed as offering a specialized BSc degree in marine biology was Fairleigh Dickinson University, whose Teaneck campus was a mere twenty-minute drive from my house. This meant I could live at home whilst attending university. I certainly wasn’t looking forward to negotiating the notoriously unattractive highways of northern New Jersey every day for four years, but I had to take into consideration the practical benefits of going to a local university virtually on my doorstep. I was also realistic enough to know that getting accepted to an out-of-state university was probably going to be difficult for someone like me with average grades and without the money to pay the high cost of tuition and living expenses.

The other attraction of FDU’s marine biology programme was that it included a half-year semester at the university’s own private laboratory on the Caribbean Island of St Croix, in the US Virgin Islands. The university’s prospectus promised students the opportunity to study in a setting in which the classroom was a pristine coral reef, with lessons taken underwater whilst scuba diving. Although there were more prestigious marine biology and oceanography programmes dotted around the country, none of them offered such a marvellous facility in this kind of exotic location. For the first time in my life I was seriously motivated to work harder in school and improve my grades, so that I could get accepted into FDU’s marine biology programme.

My only sense of what university would be like came from a short visit to my older brother during his freshman year at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. UW-Madison in the early 1970s was a hotbed of student activism, and it was also ranked by Playboy magazine as one of the top ten party schools in America. Consequently I saw very little academic work of any type the week I spent on campus. Most people I came across in the dorms were, it seemed, preoccupied with either the latest developments in the Watergate scandal or getting high, or both.

When I did finally get into university, it was nothing like I had experienced in Wisconsin. FDU was primarily a commuter school, with only a small percentage of students living on campus. It also had large international and graduate student bodies, so in general everyone’s attitude was to get your work done and get out of school rather than sticking around to party. My time at FDU in Teaneck was all about attending lectures and studying, and when I wasn’t doing that, I was working part-time several days a week in the biology department or in other odd jobs to help pay for my tuition. I saw university very much as a means to an end, and I wasn’t about to jeopardize everything I was working towards for a bit of fun. It was time to take my education seriously.

Unfortunately, my poor preparation from high school caught up with me during my freshman year. I struggled badly to keep up with the pace of lectures, and at one point my grades were so poor – my grade point average (GPA) had dropped below 2.0 – that I was put on academic probation, which shocked and frightened me. This meant I had just one more semester to turn things around, otherwise I would be placed on suspension, which I knew would spell the end of my university career right then and there. I was incredibly frustrated, because my problems weren’t for lack of trying; I spent every waking hour studying, but the results were simply not coming for me. That summer holiday I had to face the prospect that I wasn’t good enough to get the degree I wanted so badly.

I didn’t find the answer to my problem until the start of my second year, when I was placed in a microbiology lab class with a handful of bright students who all became very good friends. Whereas in my first year I’d studied by myself, now I began working in a group with my new friends, who showed me how to learn effectively and efficiently. The difference in my work, and most importantly my exam results, was immediate. In a single semester I went from nearly flunking out to getting some of the highest grades in many of my classes, especially the core science subjects that dominated my course. I still worked very hard, but armed with some new techniques and the benefit of studying in a group, I was able to put my disastrous freshman year behind me and improve my GPA to a respectable figure.

Improving my GPA became particularly important, because by the middle of my junior year I had decided to continue my education and apply for graduate school, targeting about a dozen top universities on both coasts that offered PhD and MSc degrees in marine biology. To do this I would need a 3.5 GPA – over and above the 3.0 minimally required for acceptance into graduate school – in order to be seriously competitive with the other PhD and MSc candidates vying for scholarships and the best research opportunities. I had dug a huge hole for myself with my disastrous freshman year, and the only way out of it was to get virtually perfect grades from now on.

I left for my semester in St Croix in early January, just after celebrating the new year with my family. My father had died from a heart attack the previous September, at the start of my senior year, so this was the first Christmas we’d had without him. Although he had been ill, his death was still a major shock that left a huge hole in my life. I’d been extremely close to him, having spent a large portion of my childhood helping him with his antiques business. It wasn’t an easy way to make a living. Every day he was faced with having to find and buy antiques in New Jersey and sell them later that same day in Greenwich Village, where most of his customers’ shops were based. The constant need to create these profitable market opportunities was wearing on him, and I think this was one of the reasons he was happy to have me along for company. It also helped that, with his tutelage, I had developed an eye for spotting valuable items.

Some of the best times for my father’s business were the periodic ‘clean-up’ weeks, when the nearby cities and townships in New Jersey would allow their residents to put any objects, no matter the size, out on the streets to be collected the following morning as rubbish. In the process of emptying their attics and basements of trash, people would also unknowingly throw away treasures that only we would recognize as valuable antiques. I would happily run along the sidewalk spotting and collecting the worthwhile objects whilst my father followed me slowly in his van. Working together this way we were able to cover far more ground than he could have done alone.

This might not have been an ideal activity for a young boy to be engaged in on a school night, but I couldn’t have been happier when I found something of real value, like an oriental rug. I was making life easier for my father and contributing to the family’s finances by literally turning people’s trash into cash. Of course my mother wasn’t enamoured with our late-night excursions, as she saw it as yet another excuse for me to avoid my homework. The way I looked at it, I was just helping with the family business like a lot of children were expected to do. If we had lived on a farm, no doubt I would have been spending early mornings tending to animals or taking whole days off from school during the harvest.

I learned so much from my father and I missed him dreadfully when he died. It pained me to think he wouldn’t be around to hear about my experiences in St Croix or watch me graduate from university. Despite my grief at his death, however, I was able to meet the target I had set of getting A grades in every class, and I left for St Croix with confidence that I would be able to handle whatever workload they threw at us. Despite the fact that I was the youngest in the family, I was on track to be the first to graduate university, as my brother ultimately dropped out and my two sisters worked for years before going back to college. I had studied extremely hard to recover from my nightmare first year, and now, with all my goals back within touching distance, I was determined to make the most of this next opportunity.

The moment you step off a plane into a hot tropical climate, you know instantly that you’ve been transported to a foreign land, very different from where you’ve come from. The heat doesn’t just hit you in the face; it envelops your entire body and permeates all your senses. This was how I felt landing in St Croix on a blazing sunny day after flying in from New Jersey, which was still firmly gripped in the dead of winter.

If there were any lingering doubts about how different St Croix was going to be, they all faded away when I caught my first sight of the shallow lagoons just off the eastern tip of the island where FDU’s West Indies Lab (WIL) was based. The water was a colour I had literally never seen before; a brilliant aquamarine, flashing as the sunlight reflected off ripples dancing across its surface. Despite the long flight, several of us immediately ditched our bags and hiked down to a remote lagoon to go snorkelling. I wasn’t prepared for how beautiful the corals, fish and anemones would be. Everything was so spectacularly bright and colourful. As soon as I entered the water I knew one thing instantly: that I would never go swimming in the polluted and visibly impenetrable waters of the Hudson River ever again.

The locals call St Croix a paradise, and that is never more evident than when you begin exploring the different types of coral reefs that populate the waters surrounding this small Caribbean island. Fortunately, the structure of the classes taught at FDU’s lab allowed us plenty of time for scuba diving. After morning lectures, nearly every afternoon was spent in the field – generally underwater – observing and learning about the local flora and fauna. Our first assignment was to recognize by sight all the fish, coral and invertebrate species, which meant spending countless hours in the water using waterproof guidebooks and checklists written on slate to keep tabs of everything we had to identify during our dives.

Having learned to dive in a cold flooded quarry in New Jersey, where the most interesting thing to see was a stolen car dumped there after a botched crime spree, diving in St Croix was a revelation. To begin with, the visibility was spectacular and the water so warm it made wetsuits unnecessary. The main attraction, however, had to be the communities of fish that lived within the coral reefs and made them a constant hive of activity. One of the most amazing spectacles was the daily migration of juvenile grunts, a mostly yellow and blue striped fish, which leave the reef en masse each day at twilight to feed in the adjacent beds of seagrass. When we were told that these large schools of fish would swim off in single file at a specific time every evening, I remember feeling a little sceptical, but as I lay in wait for the grunts along with the rest of my class, sure enough, at exactly the predicted time, a single grunt led a procession of his mates off the reef in a perfect line that any drill sergeant would be proud of.

As fascinated as I was with the ecology and behaviour of reef fishes, as the semester wore on I grew slowly disillusioned with the idea of becoming a marine biologist. Coral reef ecology is an enormously complex subject that relies on small advances in a wide range of different fields before even a simple understanding of the whole ecosystem is possible. I felt the pace of discovery was too slow and didn’t want to devote a large chunk of my life to a field of study in which I would only make a small contribution.

For my own research project I decided to choose a topic that I felt was of greater significance to the overall health and fate of the island’s reefs, which had begun to show the first signs of the deadly coral disease that was to decimate many species the following decade. By measuring the quantity and productivity of calcium-carbonate-producing plants and animals, including corals, spread across one of the island’s shallow bays and adjacent fringing reefs, I was able to put together the first biogeochemical carbonate production budget ever established for St Croix.

I liked this project for several reasons. Firstly, it had a mixture of marine biology and geology that I found stimulating. I had taken no courses in geology until arriving at the WIL and was surprised to find how much I enjoyed this new field. Secondly, the fieldwork was very physically demanding as I had a lot of underwater acreage to cover while counting and measuring all the carbonate producers along the half-mile transect I’d chosen to survey. I was spending up to four hours underwater every day, with one long dive in the morning and a second in the afternoon. Because the water was so shallow, decompression sickness wasn’t an issue and I was free to extend my dives by means of carefully controlled breathing until I literally ran my tank dry. All the hard work meant I was probably as physically fit as I’ve ever been in my life.

When I submitted my final paper, I received the A grade I so desperately wanted and needed, but even that was less important to me than the comment made by our marine geology professor, who wrote that the quality of the paper was so good, it actually deserved to be published in a peer-review journal, something that was extremely rare for a student paper. My work resulted in the first quantitative snapshot of the state and health of this important environment, which would also serve as a comparative baseline for similar studies in the future.

When my final GPA was calculated, however, I still fell short of the 3.5 score many of the graduate schools were telling me I needed to qualify for places and scholarships. Despite getting straight A’s in every class in my senior year, the highest I could pull my GPA up to was 3.34. In truth, I never really had a chance after my disastrous freshman year. However, I was proud that my GPA in the core science subjects that made up 60 per cent of my overall curriculum was 3.71. I prayed this was enough for at least one graduate school to take a chance on me.

When I heard that the University of South Florida (USF) were upgrading their small St Petersburg-based Institute of Marine Science to department status, with the addition of about a dozen new faculty and thus many more places for incoming graduate students, I made sure they were on the list of schools I applied to. I had been advised to apply primarily for PhD programmes on the basis that prospective PhD students had a much better chance of getting the research funding and/or financial scholarship I would need to further my education. Unfortunately, this advice proved to be misguided, for the simple reason that I wasn’t a strong enough candidate to compete for these highly coveted places. This became distressingly clear to me as the rejection letters started arriving in our mailbox.

I was getting to be quite an expert at sniffing out rejections with just the briefest of glimpses at the first couple of sentences. After reading the full contents of the first few letters, which left me with an awful feeling of having been kicked in the stomach, I would thereafter only open the top fold to glance at the opening paragraph. If the phrases ‘After careful consideration’ or ‘We regret to inform you’ showed up, there was really no point in reading the rest of the letter. This routine continued with sickening regularity until the letter from USF arrived.

At first I couldn’t tell whether I was in or out, because the first paragraph did include some of the phrases I had learned to dread. But as I began to make sense of the letter, it was clear that USF, while not accepting me outright as a PhD student, had thrown me a lifeline. In short, the letter explained that they would be happy to take me on for an MSc degree, following which I could pursue a PhD if I wanted to continue at USF. To say I was overjoyed would be a huge understatement. After so many rejections, I was relieved that any school was giving me a chance, and the fact that marine science was an up-and-coming department at USF – having recently been made a state-wide Center of Excellence and with ambitions for becoming nationally prominent – made my acceptance of their offer one of the easiest and happiest decisions I ever had to make.

Although I entered the MSc programme at USF as a marine biologist, it wasn’t long before I decided to change to marine geology. I had spent part of my first year at USF improving the research paper I had written at WIL, and my interest in marine geology was increasing at the direct expense of marine biology. I could also see that the marine geology students had more seagoing research opportunities and that they were a more tightly knit group than the biologists, who, because they pursued such different research projects, didn’t collaborate as much. In addition to what my heart was telling me, my head also liked the fact that marine geologists were far more employable than marine biologists, so making the switch was unlikely to hurt my job prospects when I finished with graduate school.

In order to change courses, I had to have one of the marine geology faculty take me on as their student, and I was very fortunate that Al Hine agreed to do just that. Al was an assistant professor who had a growing reputation as a talented sedimentologist specializing in shallow carbonate environments. Most importantly for me, he was a proper seagoing scientist, meaning that I would have plenty of opportunities to go to sea myself and get hands-on experience with the high-resolution geophysical instruments that were the tools of his trade. Al believed in taking all his graduate students to sea and giving them full responsibility for operating the expensive and scientifically powerful equipment. On my first training cruise with him, he put me in charge of a high-frequency side-scan sonar system that we used to image the sea-floor geology, and it was without question an experience that transformed my life forever.

The sonar was a decrepit EG&G 259-4 unit that was in such bad shape I had to spend a week breaking it down and repairing it just to get it working to about half its rated capability. The 259-4 was one of the earliest commercially available side-scan sonars and was notoriously difficult to operate. However, when I finally got it going and it started to produce sonar images of the West Florida continental shelf as we slowly steamed away from the coast, I knew immediately that working with this type of equipment was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

The images of sand waves and rocky outcrops, even taking into account their relative poor quality, were an absolute revelation to me. I felt this was probably the most perfect mix of science and underwater exploration that I could ever hope to find. What I found particularly powerful was the ability of the sonar to scan wide strips of the sea floor to reveal both geology that was millions of years old and sedimentary patterns created during the most recent change of tide. Before our short cruise was finished, I had already decided to learn everything I could about this amazing technology and become an expert in its use.

In order to fulfil my ambition to become an expert seagoing geophysicist, I joined every single scientific cruise I possibly could during my years at graduate school. One way or another I managed to go to sea on ten different cruises, totalling about three months in duration, which enabled me to become a proficient equipment operator. The high-resolution geophysical gear that we used included acoustic profilers, sparkers and air guns, but my main interest was always the side-scan sonar. I quickly became the department’s resident expert, and by the end of my tenure at USF, Al Hine was having me give the lecture on the theory and use of side-scan sonar to the incoming class of students.

As Al’s field research was primarily focused on the continental shelf, we were generally working in less than 200 metres water depth. I had no deep-water experience to speak of, so when I got the opportunity to join one last cruise that happened to be leaving from our dock to study a newly discovered community of cold-seep clams and tube worms found at the base of the West Florida escarpment, I jumped at it. This cruise appealed to me for a number of reasons. First, the co-principal investigator was the legendary Dr Fred Spiess of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, who famously pioneered the use of deep-tow instruments for scientific mapping of the deep seabed. Second, the research vessel was going to be the RV Knorr, which had hit the headlines just the previous year when she was used to find the wreck of the Titanic. And finally, the study area was at a depth of 3,600 metres, which meant I would be exposed to a whole new set of instruments and methodologies.

I couldn’t dream of a better way to cap off my graduate school career, which had just finished with the successful defence of my MSc thesis. This was an incredible opportunity to take part in cutting-edge deepwater research and to work with some of the best scientists in the world on the biggest and best ship I had ever boarded. Probably even more importantly, I had just run out of money for food and rent and was living on a friend’s sofa while I waited to hear if I was going to be offered the job at Eastport International for which I had recently interviewed. So I could easily add self-preservation to the list of benefits in joining a three-week cruise that offered a warm bunk and all the food I could eat.

As I had anticipated, the cruise was an unforgettable experience and I learned an enormous amount. I came away with a whole new understanding of how to deploy and operate side-scan sonars in the deep ocean and with a confidence that I was ready for my career to move on to the next level. Partly out of necessity, and partly as a tactic, I gave Eastport a deadline as to when I would be making my decision about which job offer to accept, which meant they were going to have to call me at sea on an expensive shore-to-ship connection to let me know their intentions. While I knew that the radio office of the Knorr had been the scene of some extraordinary calls over the years, especially when Dr Robert Ballard announced they had found the Titanic, I can’t imagine that many people have used it, either before or since, as the place to receive and negotiate their first serious job offer. Eastport wanted me to grow their geophysical survey and search business and I was delighted to accept. I was also greatly relieved to know that when the Knorr docked back in St Petersburg, I would be moving on to a new and exciting life and not back to my friend’s sofa.

From my first day at Eastport International, I knew that I had been given a marvellous opportunity to excel at a seriously cool and exciting company, but also that I would need to work extremely hard to get up to speed on a technical level. Eastport’s main business at the time was as a contractor for the US Navy Supervisor of Salvage (SUPSALV), maintaining and operating their deep-water remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), which were often called on in emergencies to recover US Government assets lost at sea. The company was full of engineers, mechanics, electronics technicians and pilots to ‘fly’ the ROVs – all highly skilled technical experts. My background as a scientist certainly impressed the management and helped me get my foot in the door, but among the guys I would be going to sea with it was only a curiosity. To earn their respect and become a valued member of the team I needed to know my stuff, backwards and forwards, and prove myself where it counted: offshore.

When I joined Eastport in September 1986, their forte was the recovery of downed aircraft from deep water. The company operated a SUPSALV ROV called Deep Drone 6000 that could dive to a depth of 1,800 metres and either pick up small bits of aircraft wreckage with its two manipulator arms or attach lifting lines to recover an entire Chinook helicopter if necessary. Together the navy and Eastport had recently completed the recovery of the wreckage of the ill-fated Space Shuttle Challenger, which exploded in spectacular fashion shortly after take-off, killing all seven of its crew members, including Christa McAuliffe, who was poised to become the first schoolteacher in space. The accident, caused by a failed O-ring seal on the right-hand solid rocket booster (SRB), was a horrific tragedy seen live by millions of Americans – including me, watching from the opposite coast of Florida in St Petersburg.

The recovery of Challenger was an enormously difficult project because the wreckage was spread over a huge area and pieces of the problematic SRB had sunk in the deep, swift-moving waters of the Gulf Stream. The salvage teams coped well with the difficult environmental conditions, but afterwards the navy decided it needed a more powerful ROV that could handle the worst-case combination of high currents and great depth down to a maximum of 6,000 metres – more than three times deeper than the existing Deep Drone could go. No ROV had ever dived so deep, and the development of this new ROV, called CURV III, turned into a race against another US Navy R&D centre to see who could reach this important milestone first. Because of my background in marine science, the first assignment of my new job was to compile a worldwide database of surface and subsurface currents and worst-case current profiles that would establish the key performance criteria for the new CURV. It would never have occurred to me as I watched the contrails of Challenger’s debris fall to earth on that sad day in late January that in a way I would owe my first job to that horrible tragedy.

Dealing with deadly accident scenes was obviously something I was going to have to get used to. Objects that need to be found and recovered from the bottom of the ocean generally only get there because some disaster has occurred. Sometimes we were tasked to recover inanimate objects like test torpedoes that failed to float to the surface at the end of their run, or live Tomahawk cruise missiles that never reached their intended target. But mostly it was helicopters or jet aircraft, and in those cases the chances that someone had lost their life were usually quite high. I guess that everyone has their own coping mechanism, although it wasn’t a big topic of discussion offshore. Personally I found it helpful to remember that the job we were doing to assist the accident investigation teams was vital in the prevention of future accidents.

It wasn’t long before I started to develop my own commercial clients outside Eastport’s normal base of US Navy and Defense customers. In the main these were industrial projects like the survey of proposed pipeline routes for the oil and gas industry. They were technically demanding, high-pressure tasks that were satisfying to complete but not as interesting as searching for lost objects. I had nothing against ‘big oil’, but working as a geologist in the industry, either as a geophysicist in the exploration for oil deposits or to determine the best locations for the placement of platforms and pipelines, simply didn’t appeal to me. So while these industrial projects were good, profitable work, what really got my blood flowing was when my small team was called on to search for something lost underwater.

Often the key to a successful search is getting out on the water as soon as possible after the object is lost, when the memory of eyewitnesses is still good and physical evidence is fresh. The tendency for critical information to degrade with the passage of time is well known, so speed of response is of the utmost importance. We had to be ready, with our equipment fully operational and prepared to go, at all times, which meant being on virtually constant call twenty-four hours a day. This was especially true in the search for sunken boats on Chesapeake Bay, the nearest large body of water, just ten miles away from Eastport’s offices. Our proximity to the bay was certainly bad luck for one boat owner, who, when putting his brand-new speedboat through its paces, stupidly decided to try jumping the wakes of larger ships for fun. Unfortunately for him, he mistimed one jump so badly the boat landed bow first, driving him and the entire vessel violently into the water.

From his hospital bed the next morning, the boat owner claimed the sinking was caused by delamination of the speedboat’s fibreglass hull: basically a manufacturing defect. This claim placed the blame squarely on the boatbuilders, who reacted immediately by hiring us to locate and recover the vessel to determine the true cause of the sinking. It wasn’t just the $25,000 replacement cost of this single boat that concerned them; the delamination claim, if proven, would jeopardize future sales. Not wanting the owner’s claim to gain any momentum, they asked us to move as fast as possible to start the search.

Several hours later, I was mobilized with my side-scan sonar on a small boat south of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore, trying to decide the best place to start the search. A couple of eyewitnesses had come forward to point out the general area they had seen the speedboat jumping wakes the day before. However, because their information was quite vague – no one had actually observed the boat crash and sink – I had no idea how long the search would take. Thirteen minutes later, I had the answer. A perfect boat-shaped target appeared on my sonar trace, ending the quickest search I have ever conducted, before or since. Less than an hour later, the boat had been raised by diver’s airbags and was under tow back to the dock so the builders could examine the damage carefully. When they saw that the bow had been smashed in, with no signs of delamination, they drove straight to the hospital to confront the owner. By that time my job had been done and I was on my way back to the office, but I would have liked to have seen the owner’s face when he was told his claim was being rejected, and that if he had any doubts he was free to inspect his boat himself as it was currently waiting in the hospital car park.

After the first few years at Eastport I began to take on larger and more complex projects. The company was growing steadily and new milestones were being achieved all the time, including winning the race for CURV