Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

A pivotal book for Bernstein, The Sophist demonstrated his great range of subject matter, style, and genre. By contrasting wildly different approaches to poetry, Bernstein not only questions the intrinsic value of any given form but also provides a model for his later heterogeneous books.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 133

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

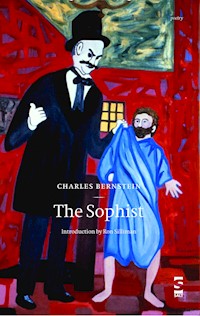

The Sophist

Charles Bernstein

Introduction by Ron Silliman

Contents

The Text, the Beloved? Bernstein’s Sophist

By Ron Silliman

In 1987, when Sun & Moon Press first published The Sophist, Charles Bernstein was already one of the dozen or so best known poets of his generation, having gained an enormous amount of visibility as coeditor of the magazine L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E (1978–81). In the eleven years since he first self-published Parsing under the Erving Goffmanesque imprint of Asylum’s Press, Bernstein had published ten additional books of poetry, a collection of essays, Content’s Dream, coedited his journal, plus an anthology based on it published by Southern Illinois University Press, as well as features on language poetry & environs in both the Paris Review & boundary 2.

In retrospect, it’s almost hard to remember the primitive nature of some of those earliest publications—not only was Parsing basically photocopied and stapled, its cover the dark blue stock you would get for a report cover at Kinko’s, but Shade, Bernstein’s first “large” collection from Sun & Moon was stapled & Xeroxed as well, the first volume in that press’ Contemporary Literature series, an edition of just 500. With the exception of the S.I.U.P collection from L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, Bernstein’s publications up to 1987 had all the features of any poet in the small presses. Some came from presses that disappeared quickly, such as Pod Books or Awede. One, Islets / Irritations, was initially published by Jordan Davies, who, in lieu of having a more formal imprint, simply listed his name as publisher. Others were either slender suites suitable for chapbooks, such as Stigma, or, in the case of both Legend (co-authored with Bruce Andrews, Ray Di Palma, Steve McCaffery & yours truly) and The Occurrence of Tune, contained just one poem.

viiiRegardless of how or where they were printed, Bernstein’s first three large collections, Shade (1978), Controlling Interests (1980), and Islets / Irritations (1983), were impeccable instances of the well-constructed book of poems. Indeed, after the publication of Controlling Interests by Roof Books, Bernstein’s reputation as a major American poet has never been in question.

An unwritten premise of the well-formed book of poems has to do with the self-similarity of its contents. The poems tend—that verb’s flexibility is important—to look alike. They’re approximately the same size, the line lengths and stanzaic strategies similar from poem to poem. If the poems are all relatively short, there may be one or two longer ones, or a suite of linked shorter pieces, that constitute the organizing works around which the book is built.

In the 1950s and ’60s, the form was so set that the Wesleyan poets of that generation in particular appeared to have come all from the same cookie-cutter, regardless of any differences otherwise between poets: the “major” work could be a poem between six and 15 pages long, surrounded by shorter pieces that tended to be one or two pages each. That’s a form that John Ashbery would caricature mercilessly in his “award-winning” pseudo-academic period of the 1970s & into the ’80s.

By the 1980s the form has loosened up a little, but only just. There are more books with “longer” poems—five or six pages apiece—but self-similarity is still the organizing principle underlying the construction of most books. Louis Zukofsky, whose longpoem “A” represents the most thorough meditation on part:whole relations within the poem, touches on this aspect ever so lightly with “A”-16, a four-word text set alongside others that go up as high as “A”-12’s 135 pages. But it appears that it never occurred to Zukofsky to stick a section of “A” in amongst the poems that will eventually be compiled into Complete Short Poetry when they appeared in individual collections. Similarly, Olson never thought to mix Maximus & non-Max poems into a single volume, tho generally only the most devoted Olson acolyte could tell what constituted a Max & what did not. The volumes of Robert Creeley, Frank O’Hara, Jack Spicer, whomever, all follow these same unwritten rules. ixAs do virtually all of the early volumes on the language poets.

Consider, for example, alternative genres. CDs (or, earlier, tapes & records) from music, or gallery exhibitions of visual artists. A painter may work in different modes, but generally a given exhibit is going to focus on just one, or possibly two that are very closely related. Mickey Hart is not about to bring his anthropological explorations of drumming to his recordings with the Grateful Dead. Brian Eno & Gabriel Byrne put their sound collage pieces onto a single album, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, rather than their own records. Part of what made Harry Partch, the hobo composer who worked not only with invented instruments but his own 72-tone scale, seem like such a nutjob was that some of his self-issued recordings included not just his works, but dry, even tedious lectures about his theories of music.

The Sophist is a jumble, a jungle, a jangle of—dare I say?—overdetermined elements hodged-podged together. If it has an antecedent—there are in fact a few—perhaps the most direct is the conservatory at Citizen Kane’s Xanadu, an interior shot for which the ever-resourceful director Orson Welles (a man with more than a little of the Bernstein in him, or verse visa) matted in footage from an old RKO pre-historic adventure. Thus in the background of this too-lush garden one sees a pterodactyl in flight. Work after work in this book proceeds likewise, the obvious & the impossible in a constant, slightly frenetic mambo, not by virtue of reinforcing & building upon the unwritten law of self-sameness, as books of poems are supposed to but rather just its opposite—as if each text were antithetical, pushing as hard as could be to establish a new space not announced or even fathomable from what’s come before.

Bernstein himself says as much at the outset of the opening poem, coyly titled “The Simply”:

Nothing can contain the empty stare that ricochets

haphazardly against any purpose. My hands

are cold but I see nonetheless with an infrared

charm.

xSentence after sentence in “The Simply” skates always in different directions—ricochets is very literal here, as is the claim that Nothing can contain this—until, seven pages downstream, one arrives at an equally straightforward denouement:

“You have such a horrible sense of equity which

is inequitable because there’s no such

thing as equity.” The text, the beloved?

Can I stop living when the pain gets too

great? Nothing interrupts this moment.

False.

As is always the case in Bernstein’s work, that which appears as if written “haphazardly” is in fact obsessively scripted—equity in that first sentence in all of its conceivable meanings, including in that last instance real estate. Similarly Nothing interrupts is not the denial of action, but rather the naming of its actor. It’s a dizzying performance, intended I think to connect the reader with the Bernstein of his earlier books, familiar in his lushness, dazzling in the constant display of jaw-dropping devices, drenching us in the humidity of these tropes.

It took me more than one reading of The Sophist to understand why, at the conclusion of “The Simply,” Bernstein takes a step back rather than going forward. I think it is to lure readers in, particularly those who have not yet sipped from the langpo Kool-Aid. On the surface, at least, “The Voyage of Life” is a simpler, more traditional poem than “The Simply,” whereas the works that immediately follow thereafter:

A dense prose piece bordering on a story entitled “Fear and Trespass”The daft one-act play entitled “Entitlement” (it might have been called “Seven Scenes in Seven Pages”) whose characters consist of Liubov Popova, Jenny Lind, and John MiltonA poem titled “Outrigger,” whose text comes across as carefully bonkers, its lineation—its key relationship to the xiprinciple of self-sameness—extra leaded, literally, lines spaced more or less at “one-and-one-half spaces”“The Years as Swatches,” a long single stanza composed of very short lines—only one line runs four words long, only six run threeAnother story, “The Only Utopia Is in a Now (Another Side of Gagenga … frent)A 16-line two-stanza poem entitled, “From Lines of Swinburne”Another poem, “Special Pleading,” that opens up its lineationA poem entirely composed of short bits divided by asterisks in the manner of Ted Berrigan“Dysraphism,” one of Bernstein’s signature poems, roughly in the manner of “The Simply,” whose title Bernstein explains in a rather chatty footnote“By Cuff,” a poem of just five linesFlew, then flew

through the hall

then flew

a wasted monument

recalled to perfidy

WheTHer oriented or RETurned tO

sTAndiNg poSTurE

ACCUMULAteD

advicement and bASicALly

Try sneaking that one through spell-check. The purpose of this list, which characterizes the first 50 of over 170 pages, is to give a sense of how like a gyroscope The Sophist proceeds, perpetually off-balance, lunging, lurching from text to text, its only “center” something that each of this works conceivably points to but which proves impossible to nail. It is somewhere in between all of the above.

xiiSeventeen years later, after books like Charles Bernstein’s A Poetics and My Way, The Sophist doesn’t necessarily look as radical to the eye as perhaps it once did. Significantly, both of those texts are more apt to be characterized as critical—collections of essays into which poetry “intrudes.” Bernstein’s own books of poems, such as With Strings, have in fact moved back to something closer to what we might expect from a “normal book.” At least the selfsame principle appears more visible there. That something that has taken deeper root in Bernstein’s “professional” writing than in his “creative” work should have shown up first here in The Sophist is itself worth thinking about.

As are precedents. The two I think are most visible are William Carlos Williams’ Spring & All, a volume that appeared nearly 50 years before anybody was ready to “get it” back in 1923, mixing Williams’ most deeply condensed poems into the hot broth of the most radical poetics text that had, at that late modern moment, been written. Williams’ book sunk more or less without a trace, odd enough under any circumstance but positively bizarre given just how famous some of its poems—“The Red Wheel Barrow,” “The Pure Products of America”—later became, tho largely due to being read in WCW’s various collected editions. It wasn’t until Harvey Brown produced what may have been a pirate edition of the original volume in 1970 that a much later generation of poets found themselves dumbstruck at the brilliance of Williams’ total project. I would argue that the organization of The Sophist follows Spring & All not in its “linked verse in a critical frame,” but rather because the construction of the book itself is understood by its author as a critical act. Which is why it follows that this principle follows Bernstein into his prose more than into his later poetry.

The second source is one that Bernstein sort of half gives away in a title’s allusion amidst the poems I listed—Robert Duncan, particularly the Duncan of Roots and Branches & Bending the Bow. In many respects, The Sophist is very nearly a direct descendant of Duncan’s project, mixing as the San Francisco writer’s did prose, plays, individual poems, translations, as well as—contra Zukofsky, contra Olson—sections of his ongoing long works, Passages and The Structure of Rime. xiiiBut whereas Duncan understood his commingling of divergent texts as part of a larger organic relation that could be traced back to his life (with some fudging as to chronology in the process, especially in the first of his trio of books, The Opening of the Field), the New Yorker Bernstein doesn’t buy into the mystical self-justifications—a defensive wall more than anything else—that Duncan erected around his work. Bernstein’s text in this sense forms an argument, not an autobiography. It is worth noting that in the opening of “Outrigger,” the piece that immediately precedes “The Years as Swatches,” Bernstein adapts a device taken directly from Duncan’s “The Fire, Passages 13,” a little grid of phrases apparently with no connection one to the other that nonetheless build tonally.* “The Years as Swatches” appears more Zukofskian with its hyper-narrow lines than the echo of Duncan’s The Years as Catches might suggest, but its concerns with speech & the ontological status of language directly address this question:

Voice seems

to break

over these

short lines

cracking or

setting loose.

I see a word

& it repeats

itself as

your location

overt becalm

that neither

binds nor furnishes:

articles of

cancelled

port

xiv

in which I

see you

&

changed by the

mood

return to

sight of

our encounter.

My heart

cleaves

in twos

always

to this

promise

that we

had known but

have forgotten

along the way.

Maze of chaliced

gleam a

menace in

the eyes

clearing

once again.

Gravity’s loss:

weight of

hazard’s probity

remaindered

on the lawn’s

intransigent

green.

Funds deplete

the deeper

fund within

us lode no xv

one has

found.

And yet

as if, when all –

should current

flood its

days

& self

renounce

in concomitant

polity.

This is one of those moments, and poems, in which one might say Bernstein is being startlingly literal. He means this. The argument here between politics (the market) and the self (“the deeper / fund within”) comes down clearly in favor of the Enlightenment, even if it is an Enlightenment thoroughly conditioned with a hard-earned cynicism. It is precisely this commitment that will enable the most comic poet of his generation to be, in the same moment, one of the most political.

The Sophist in this sense is a hinge text, for Charles Bernstein & for poetry.

* Bernstein will return to it again later in the ninth section of “A Person is Not an Entity Symbolic but the Divine Incarnate.”

The Simply

Nothing can contain the empty stare that ricochets

haphazardly against any purpose. My hands

are cold but I see nonetheless with an infrared

charm. Beyond these calms is a coast, handy but

worse for abuse. Frankly, hiding an adumbration of collectible

cathexis, catheterized weekly, burred and bumptious;

actually, continually new groups being brought forward for

drowning. We get back, I forget to call, we’re

very tired eating. They think they’ll get salvation, but

this is fraudulent. Proud as punches—something like

Innsbruck, saddles, sashed case; fret which is whirled

out of some sort of information; since you ask. We’re

very, simply to say, smoked by fear, guided by

irritation. Rows of desks. Something like after