Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

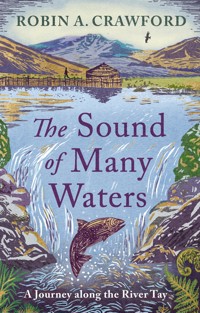

With the widest catchment area of any river in Britain, the Tay drains much of the lower Highlands of Scotland. A vast network of lochs and smaller bodies of water feed the Isla, Garry, Tummel, Almond and Earn, which all flow into this mighty river. As Robin Crawford walks along the banks of the Tay, we delve into the history of this landscape and his personal connection with it, from hill walks with friends into the mountains of the Tay's source to his student days in Dundee, where the Tay eventually spills out into the North Sea. Along the route we dip into the river's story: the gold-panners on the river Cononish, the Earthquake House outside Comrie, Beatrix Potter's holiday home near Dunkeld. Throughout, the river is our constant companion, connecting the small moments on which events turn and lives are changed forever.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 452

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Sound of Many Waters

The Sound of Many Waters

A Journey Along the River Tay

Robin A. Crawford

This edition first published in Great Britain in 2025 byBirlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

wwww.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Robin A. Crawford 2025

The moral right of Robin A. Crawford to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78885 774 1

Extracts from ‘The Cailleach’ and ‘What the Pool Said, on a Midsummer Day’, published in A Handsel: New & Collected Poems (Polygon, 2023), were printed with permission from the publisher.

The publisher acknowledges support from the National Lottery through Creative Scotland towards the publication of this title.

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Papers used by Birlinn Ltd are from well-managed forests and other responsible sources

Printed and bound by Clays Elcograf S.p.A.

To brothers,the drowned and the saved

Contents

Map

Tributary

Breadalbane

From the source at Ben Lui to Crianlarich

Loch Tay

From Glen Dochart to Kenmore

Atholl

From Strathtay to Dunkeld

Glen Almond

A Tryst

Strathmore

Isla and Ericht

Perth

The Sound of Many Waters

Strathearn

Romans, Christians, Jacobites

Perth to Dundee

North-east Fife and the Carse of Gowrie

Dundee

City of Discovery

Firth . . . and firth

The seas beyond

My Riverscape

Looking and reflections

Outflow

Sources

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Tributary

Drip. Drip. Drip. High above Loch Tay, the rain drops from the sleeve of my waterproof jacket on to my hand. The fingers are spread, like a delta. From the tips, the water drips on to my waterproof trousers. It forms tiny streams, conjoining with others – like the blood in my veins under my waterproof skin – until a micro river system of water is flowing off me and on to the summit of Ben Lawers beneath my feet.

In Turner-esque clouds, each drop is refracted by heavenly light into its constituent rainbow colours. The river has many sources, but all begin in clouds like these, blown in from far out on the ocean, sometimes deposited as snow on mountaintop or in sheets of rain on bleak moors, then filtered through tiny mosses, or, having seeped beneath our earth, welling up from deep underground caverns.

I watch as a gust of wind blows a drop into a rivulet. At this altitude a matter of centimetres dictates its flow eastwards, westwards, north or south. Such vagaries shape the lives of those who live and die by the river – the creatures, the plants, the people. A twist of fate, an act, small or big, changes histories.

*

GALLANT DEED

Three sons of Mr Mitchell . . . went into the water hand-in-hand, and by some means one little boy . . . sank into a deep hole out of sight. His older brother, James (14), seeing the little fellow thus likely to be drowned, plunged down to the bottom, though he could not swim, and with a heroism worthy of the stake at issue, crept on his hands on the bottom of the pool, seized hold of his brother, gave him a vigorous push out of the place towards the shore, which had the desired effect in saving him, but most unfortunately James, the gallant hero of the noble deed, sank himself, and was drowned . . . The younger Mitchell, who for some time appeared in a critical position, recovered. Numbers soon appeared at the water’s edge, and by the aid of creepers pulled out the body.

At the end of a long life the youngest Mitchell brother commissioned a stained-glass window to be installed in the local church at Alyth, Perthshire. In the heavenly rainbow light, Christ walks on water before his own sacrifice:

And Jesus, walking by the sea of Galilee, saw two brethren, Simon called Peter, and Andrew his brother, casting a net into the sea: for they were fishers. And he saith unto them, Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.

– Matthew 4: 18–19

*

Standing on the bridge over the river Isla, I watch two boys fishing, casting and recasting. On the opposite bank, a funereal heron is immobile but misses nothing. The river, like time, slips by. The peaty mountain stream glints over the golden gravel shallows in the August sun before it flows into shadow and unknowable depths and currents. As I stand, firmly anchored on the solid stone bridge, it is disconcerting to watch the cooling liquid, flickering under the momentary flames of evening sunlight, moving under your feet. I think of James, who thrashed from life to death in moments in this very water, from the earthly paradise of youth. And – with tears welling up, dripping down my cheeks into the water below – of his brother, my great-grandfather, emerging, spluttering, gasping, reborn back into life from this river.

*

The Isla is one of the Tay’s largest tributaries. It has many. With the widest catchment area of any river in these islands, at 3,000 square miles, the Tay drains much of the lower Highlands of Scotland. It draws its waters from many sources – as far west as Argyll and the Rannoch Moor, as far north as the Drumochter Pass, as far east as the Firth, where it discharges into the North Sea. Hold up your left hand, palm facing away, and spread your fingers: if the Tay is the index finger, then imagine your thumb as the Isla, flowing in from the east, your middle finger the rivers Garry and Tummel from the north, and from the west the ring finger represents the Braan and the Almond, your pinkie the Earn. Behind these rivers lie a network of lochs that gather the rainwaters dumped by Atlantic clouds on the Highland massif. Loch Ericht, Loch Rannoch, Loch Lyon, Loch Tay, Loch Tummel and Loch Earn are the largest, but many, many more bodies of water feed into the main river.

The river flows from source to sea, as does my journey in this book, but it does not end there. Twice every day the tide pushes the waters of the Tay back up the Firth. And while the structure of my writing flows geographically from Ben Lui to the North Sea, over time I have followed the Tay as it pushed its way inland, only to return to the sea once again. My journey along the Tay took place over many years – the writing of it began one midsummer’s day in June six years ago as I dipped my bare feet in a peaty pool in Rannoch Moor, but the story started decades, indeed centuries, before. It arcs from my family, who for generations have lived by the Tay, to my childhood visits to them, dips into my adolescence as a student on the banks of the Tay, then flows back with my adult years, working by this same river, and so then onto the next generation, with my son, born in Dundee.

The themes that ripple through the book are expected: the river’s natural and human history, and our interdependence with it. There’s swimming (elegantly by frogs, more wildly by humans) and fishing (by humans, for salmon, of course, and whales, and by herons), and bridges (built elegantly but also disastrously). Poetry, art and sculptured stones all illuminate this river.

But there are also some unexpected themes which surface: brotherhood, the sound of ringing bells, the lowing of cattle, and again and again I am drawn to the small acts that change lives.

This journey took many years and, like the Tay, takes many forms: it is never the same twice.

Breadalbane

From the source at Ben Lui to Crianlarich

Bràghaid Albann, Breadalbane – Upper Alba – is one of the old Scottish provinces. It includes most of the Tay’s Highland sources, and within these catchments are Ben Lui, Strathfillan in the west, and the Rannoch Moor and its lochs in the north. Its eastern border is the A9 and the River Tummel, and in the south it is Strathearn. Once part of the neighbouring lands of the Earls of Atholl, it was removed from their possession and awarded to the Campbells of Glenorchy (who we shall meet later) by James II for the apprehending of his father’s Atholl assassins. It is mountainous and wet.

On 1 January, I set off in darkness from my home on the south bank of the Tay to find the source of that river. There are barely a dozen cars on the sixty-mile route to Ben Lui. On the journey, dawn has smudged barely noticed into day. It creeps up on me as stealthily as Hogmanay, when you go to bed early and wake unwittingly to a new year (if you haven’t been disturbed during the night by the neighbour’s forced jock-ularity).

A new year. For well over half a century I’ve been experiencing it, and into this one comes a constant and welcome presence. In the car park at Dalrigh my brother Mark draws up as I wash down a piece of Christmas cake for breakfast with already tepid coffee from my flask. We don’t really do the festive thing – I’m usually working and he has recently taken to spending the holidays on cycling tours in the Middle East. He’s just back from Jordan. Mountain biking along dry wadis, floating in the Dead Sea – it’s a bit different to the West Highlands in the first week of January. We hug and exchange gifts. For me, a CamelBak water bottle; for him, thick hand-knitted socks from the Hebrides.

We’ve met up to climb Ben Lui and find the source of the Tay. At 3,710 feet, Ben Lui, or Beinn Laoigh (‘the Mountain of the Calf’), is one of the thirty highest Munros in Scotland.

As we slip on our waterproofs, we discuss the Tay. We both first encountered the river when crossing the then new road bridge by bus as children.

‘I was scared,’ I confess.

The bridge seemed to go on and on. Of course, there are shorter ferry crossings – it really was like travelling to an island, to a different world.

We were going to visit our great aunt and uncle at their house on the Blackness Road. There were terrific views from their conservatory south over the river, and we sat in there eating pink jelly, entranced, watching the trains snaking over the railway bridge. It was like a step back in time, as visits to elderly relatives can seem to young children, especially if like Tot and Mac they didn’t have grandchildren of their own.

They told us of the old wooden battleship that used to be moored across the river that was a home for orphans and bad boys, pointed out the piers of the old bridge that collapsed into the river, taking a train and all the passengers with it one new year. Everything in their house seemed old-fashioned: dark wooden furniture; sepia photographs – a man wearing a pith helmet on a camel by the Nile, a grave in India, an old soldier in the kilt. Their own clothes were different from ours, woven from tweed, not the least bit as beautiful and modern as our dad’s belted safari suit and mum’s polyester orange-and-brown mini-dress.

I wish now that I could go back in time to listen to their stories and family gossip, but we were more interested with the old Anderson shelter in their garden, an underground playhouse full of Second World War treasures.

On leaving, Uncle Mac gave us a big hardback book entitled The Wonderful World of Nature, which was new and full of brilliant colour photographs of plants, animals and fish, and on its dust jacket a plunging waterfall cascaded into tropical forest from an Andean mountain. In retrospect that visit seems to have had a significant effect on the future course of my life.

It’s a bit of a hike in before the ascent starts, so we’ve brought our bikes to speed up our journey. With short daylight hours, we want to maximise our time on the hill. Almost immediately we are free-wheeling through water, the Crom Allt, which flows crookedly out from Tyndrum and joins the river Cononish just below the car park. Our route takes us up this convergence of streams flowing off the mountain at the foot of Ben Lui. Our aim is to climb straight to the summit, then follow the ridge down to the bealach between Bens Lui and Oss. This route allows us to pass through the snowfall above Coire an t-Sneachda, the highest point that the Tay flows from on the mountain (2,600 feet), and then along to the watery, boggy pools that are its actual source at about 2,275 feet.

The river’s waters may have their source here, but what of its name? It is only after being Allt Coire Laoigh (‘the Stream of the Corrie of the Calf’), the Cononish, the river Fillan, Loch Dochart, Loch Iuibhair, the river Dochart and Loch Tay that finally the river Tay proper begins at Kenmore, 40 miles north-east from the source. And these are only the direct water courses. In the less than two miles it takes Allt Coire Laoigh to merge with the Cononish, it is joined as it flows through the glen by at least twelve other streams, many themselves formed of multiple lesser burns.

Throughout my journey, I find myself wondering what is the Tay? Where does it begin and end?

Thanks to a team of surveyors from the Tay Western Catchments Partnership this exact source on the mountain was only confirmed as recently as 2011. In this liminal zone, the tiny nuances of geography are illustrated. On the boundary between two mountains and two corries the water in one boggy pool flows north-east and becomes the Tay; it is then carried to the North Sea a hundred miles away. In an adjacent boggy pool, the water flows south-west, and through Loch Lomond it enters the Clyde and eventually joins the Atlantic Ocean.

The road that runs parallel to the Cononish here is wide and grey-gritted. Heavy lorries servicing the latest attempt to mine gold commercially from under the mountain rumble down it. Cononish Farm – lean, functional, weather-defiant – sits between road and mounds of glacial deposits on the narrowest of valley floors along which the river twists. Over on the other bank it’s only a few metres before the steep mountainsides rise again, discharging more scurrying waters into it.

Beyond the mine the road narrows to a track, constructed of small stones and grit dug out from surrounding glacial deposits, fenced by barbed wire to the right, dropping sharply down to the river on the left, a river that now gurgles throatily as it hurries past you. I envy its vigour.

Glad to dismount, we chain up our bikes by a rusting iron-barred sheep fank and stomp off upward, sticky with sweat, through a toffee-coloured landscape. I take time to look closer at the colours of withered brackens, the heathers and mosses of these, the foothills: rusted reds, burnt umber, oranges, pale yellows, dead fawns, muted golds. In them this place has a bleak beauty; in this vegetation thinly laid over raw geology and cut through by water whose only imperative is gravity, there is beauty but of a strange kind.

Geology and glaciers have sculpted Ben Lui with a shape that appeals to our idea of what a mountain should look like, its alpine and supposedly feminine form garnering it the epithet ‘Queen of Scottish Mountains’, or sometimes just ‘Queen of the Southern Highlands’. As the Cononish and Allt Coire Laoigh meet, thick cloud is veiling the mountain’s beauty. As we start to climb steeply, my thighs are cramping; the shock of cycling up the track has flooded my leg muscles with poisons. Starved of oxygen, they feel like bags of stones.

We are following the Allt Coire Ghaothaich straight to the north-eastern corrie. As the waters gambol and scamper I drag myself upwards.

Ahead it seems pockets of snow have formed regularly by the route, but as we get closer we see that they are white builders’ bags. Full of rocks and boulders to repair the path, they have been helicoptered onto the mountain. By the time I step up to the last of them, puddles on the crumbling path are turning to slush under our boots; soon, they solidify to ice. Water lies between hummocks of fawn bog grass and exposed brown peat. The allt is plunging down a black gorge carved by glacial ice or molten liquid rock, a series of spillages from a tumbling white paint pot. Looking back, the path we have come up is a series of watery zigzags of cracked and flaked rock among textured dots of beige moor grass. It also becomes clear that visibility is deteriorating: the cloud has closed off the surrounding world. As the waters freeze and the hill around us closes in, I start to slow, each step becoming thicker, the toes of my boots catching a recumbent rock or sunken boulder, panting my breath. I take more frequent breaks as the water flows faster. Like my lungs, the allt constricts but – opposite to me – it speeds up as the going gets steeper. It takes fewer breaks in ponds and pools. Below a thatch of reedy grass it bubbles and gurgles, frothing and burbling where it falls down upon itself. In the act of falling the splashing droplets have, on or soon after impact, started to freeze – from animation to suspended animation. The cryogenics of the mountain will hold them until spring – unless a heavenly shaft of random sunlight should discover the drop and resurrect it for the resumption of its journey.

We keep climbing. Up, rest, resume. The icicles forming in the bog grasses and mosses fringing the burn are refreshing to sook until our fingers go numb. Waterproofs keep us dry and warm even as, despite wicking, underneath our sweat is pouring as we overheat. But stop and instantly we start to get cold.

‘Keep moving up,’ we tell ourselves, though our legs are wanting to rest, aching to turn around and flow with the water back downhill. We are climbing with our heads and will as much as with our bodies.

We reach the bowl of the corrie under the ridge and rest. Here it is relatively flat, a respite before the steepest ascent. The waters are slower here, forming pools, the allt widening in places, pulsing rather than rapid like our breathing as more oxygen pumps into our blood. Slowness exposes the water to the cold hand of winter and around the glacier-deposited boulders it has turned to sheets of ice. While I stand and cool, Mark is never still. He’s off in search of a route up the ridge. I look back, still pechin’, but beyond the cliff-like edge of the corrie 30 feet away all I can see is grey hanging cloud. Above the bowl of the corrie it swirls on the updrafts, and a sudden patch of blue sky reveals the dark ridge above – crags lined white with snow, and under the scree fading in from grey a monotone of dull olive grassland. Across it, shallow scars where the very beginnings of water ‘flows’ – not yet able to be called streams – have come together to form a common path. Just as suddenly the gap disappears and our cloud-enclosed world returns.

A shout from Mark and we are off again. It is hard going. Water runs down rocks and the crags of my grimacing face. It has stopped forming any kind of river now. It is a series of wetnesses, individual drops with a shared imperative. We too withdraw within ourselves; our chatter slows as we draw on our desire to reach the top, to push on to our goal as the physical effort becomes harder. We focus on the next step. We search out the handhold above us. Fingers numb as the thinning, slowing water becomes prey to the cold. We push against the rock with boots slipping as much as through exhaustion as because of ice.

Although our ascent has been up the steepest side of the mountain it has been sheltered from the south-west wind. On reaching the ridge to the summit the prevailing wind blasts us. It is cold – so cold that the sparse vegetation has been frozen in a northeasterly direction. Rain water, melted snow, dew, cloud mist – all have been blown by the wind along the length of the grass stalks and on reaching the tips have frozen in an ice lozenge. These shatter underfoot between boot and ice-glazed rock like Fox’s Glacier Mints. The bitter winds have frozen the same waters to the bare, exposed rock, flecking the black canvas white with frenzied strokes of a paintbrush and forming a thicker rim of white at the edges. It has solidified the moisture inside the exposed peat, cracking it like a dried riverbed in drought. It has cemented together the gravel of the mountain, turning each step into a delicate test – it’s as if we are walking on a frozen lochan’s brim. As we edge up the ridge, the frozen grasses get shorter and shorter until all is iced rock. The wild wind is forcing us to bend, unable to stand upright in its cauld blast. The cloud is now completely enveloping us, visibility down to a few metres.

We are at 3,500 feet on a narrow ridge, sheer drops on both sides. Underfoot we are walking on ice. We cannot stand up, so instead crawl on our hands and knees, one behind the other. Even travelling like this we are slipping. For a moment I imagine the young Mitchell brothers edging in a line out into the River Isla.

Our brotherhood means that we take the right decision and stop. We look out for each other, no egos involved. We have climbed plenty of hills together; we can always come back. We turn and in small, controlled slithers start to flow back down the mountain.

From an icy world wrapped in cloud we emerge into a dun upland. Back down at 2,300 feet the cloud thins and a vista opens up along the glen to Dalrigh. It is an umber world, a ginger world save for some faded dark green rectangles of conifer plantations, a damp world, a world of wisping cloud. Through the middle of it runs a stream, the Cononish. We are looking into the future, looking to where the waters now at our feet will soon be, and also where these feet will be on this journey from source to sea. It feels that we are now in sympathy with the river, following its direction of flow rather than struggling against it, that our futures are now running in parallel.

Here on this mountain is the misty world of the Tay’s creation. Among dewy pearls on bog grasses is the purling sound of water rising up. From a pool no bigger than my hand it bubbles, gurgling like a baby. This nature’s child is cocooned in a green mossy blanket. Without forming any kind of rivulet or channel, it runs downwards, nurturing two lines of green sphagnum: thriving, vital, luminous among the waning brown of soil-based vegetation. Cupping my hands, I slake my thirst. Slipping through my fingers, dripping from my chin, it rejoins the flow and with a breathless gush disappears over a rocky precipice. I am slower to follow – going downhill is never as easy as you imagine it to be when you are struggling upwards.

The waters start to form a recognisable stream, the Allt Coire Ghaothaich. The flanking areas of moss widen, the flow starts to speed up. Green weeds like those growing at the seaside cover the black rocks here at the source. White pebbles veined red shine, polished by the now fast-flowing burn, turning itself left and right like a child’s marble run. The black water forms white bubbles as it swerves either side past rocks or flows over the ones it can’t avoid. The sound is of bath taps running but the plug pulled out. Unrestrained, it careers on downhill into its chosen path. It is powerful enough to wash away any soil from a section of mountainside, stripping it all the way back to the rock. Over this bedrock and these boulder beds it sends watery fingers spraying, like pipes that have burst in a hard frost. A cascade. As it reaches the base of the mountain it straightens and is joined by its twin, the Allt an Rund, flowing round from the mountain’s west face. They run together until they are joined by the Allt Coire Laoigh. With the three Ben Lui streams now joined, they form the river Cononish and celebrate with a short but dramatic dive over the Hole in the Wall waterfall. This marks the upper limit of the Tay’s many fish spawning grounds. This feels like a significant place. The natural limit of the world of fish and people ends, and a temporary world inhabited by hillwalkers and seasonally grazing sheep begins.

*

Under the mountain something twinkles, enchants. Deep below the foothills of Ben Lui is gold! Strewn through the Dalradian metamorphic complex rock are thin galaxies of precious metals in this deep space. The mountain has been tempting and frustrating prospectors for years. The profitability of excavating its running streams of both gold and silver have fluctuated as their prices vary on the ever-changing world markets – when gold supply dries up and prices rise, the £25 million capital and £75 million operating costs become viable, but when it sinks, those costs-to-profit ratios are just too high to make mining worthwhile. Even when successfully excavated, the more gold extracted, the less unique it becomes, and so the price drops again. Deep underground in Hades, Tantalus stands thirsty in his ever-receding pool of water, ever stretching for lush fruit in the tree’s out-of-reach branches.

On the surface, the pale daylight glints on the small-time but no less avaricious panners in the river Cononish. Even when the sun is at its nadir these prospectors are drawn to the bright solar gleam of gold. They have the patience of marksmen lying for hours flat in the freezing stream. I guess that makes sense of their nickname – ‘snipers’. In drysuits with sieves and trowel they search, scouring for that elusive gleam out of the darkness of the stream bed, a nugget of hope. They stir and probe the nooks and crannies among the rocks where a tiny fragment of gold may have been washed. The gold, being heavier than the grit and sand, falls to the riverbed fastest. Any tiny flake that glimmers in the water is sucked up into a waiting squeeze bottle. They dig and sift, dig and sift, and all the while the river flows past and beyond them. Like words written and read down a page, minutes become hours and suddenly the day has passed and the long night of winter has set in.

Time, its elasticity and its passage, flows with the river. The geological forces that formed the Dalradian metamorphic rock at Ben Lui operated in a time whose scale is beyond seasons, human lifespans, the existence of life on this planet. The land that is now cut through by the Tay and its tributaries was formed by the smashing together of tectonic plates that had been in flux for such a vast period of time that they had travelled north from the other side of the equator. The hard Precambrian and Cambrian rock of what is now the Highland massif crashed up against the softer sandstone of the southern plate, forming the fissure known as the Highland Boundary Fault, which cuts diagonally across Scotland. When water flows over that line it forms waterfalls, cataracts. Along the fault at Comrie in Perthshire, halfway between the Tay’s source and firth, is the Deil’s Cauldron waterfall, which is spectacular, especially after heavy rain.

At Comrie not only do the waters move but the earth also. It is said to be the most seismically active area in Scotland. An Earthquake House was built there in 1874 to monitor geological activity. This was done by means of a ‘Mallet seismometer’, a basic but effective method of recording the strength of any tremors using a series of wooden cylinders balanced on a wooden cross set into the rocky floor. Different cylinders would tumble depending on the strength of any quaking. Today a modern seismograph has replaced this basic but effective science, though you can peek in a window and see the original nineteenth-century wooden ‘X’ marking the spot.

Despite the odd tremor, Tayside is now an area of geological stability. In contrast, the formation of this landscape began with the folding, flowing and crumpling of molten lavas in the Highlands 490–425 million years ago. From about 320–290 million years ago, the softer Devonian and Carboniferous rocks of Midland Valley formed, sedimentary and volcanic. All were compressed, buckled, twisted, flowing into and out of each other in eddies and whirlpools and liquefactions.

When I went for a walk beside the Deil’s Cauldron I’d not long returned from a trip to Iceland. I was struck by that volcanic landscape just north of us, its newness and its molten fluidity. Throughout my life that north-east Atlantic island landscape has been in a state of flux – the Heimaey eruption in the early seventies; Eyjafjallajökull in 2010 that brought air travel around Europe to a halt for several days; and in the past year on the Reykjanes Peninsula. In the calm of the pool below the bubbling ‘Cauldron’, layers of water-borne proteins are churned by their passage through the waterfall into foams. Subtle creamy tones ranging from pale white to fawn define each layer, which form strata at the end of the pool furthest from the falls. Their textures also vary: those most recently added were airy with big bubbles, between them the black malt stout colour of the pool’s peaty water. As more foam joins, these are compressed, popping, deflating, becoming denser until pressed against the moss green rocks of the chasm’s edge. They cover the surface of the water with a foam blanket, its texture like grained wood. It also reminded me of an exhibit in the National Museum in Reykjavik, a cross section cut through the Icelandic earth that was similarly stratified but this time each dark horizontal line was the fallen ash from a volcano that had covered the land, its thickness dependent on the power of each eruption. Today in Iceland, ‘the land of fire and ice’, the danger to living creatures like us is not only from the exploding volcano but that the heat released will melt the ice and cause flooding. Melting ice, and the consequent grinding movement of glaciers carving into Tayside’s ancient rocks, has sculpted the landscape of the river catchment we know today. Underneath, traces of its ancient formation can be discovered within the rock itself and the claybeds left behind by retreating glaciers.

Downstream of the Hole in the Wall waterfall I look into the waters of the Cononish, searching for fish. I spot a smolt languidly holding position in the icy current. Victorian fossil hunters excavated the carcasses of fish that once swum in the waters of an ancient world and had sunk to its seabed and petrified. Four hundred and ten million years later, they were hewn out of the Devonian sandstone at Balruddery Den, near Invergowrie in the Tay’s firth. In Perth museum today you can look upon the plates of one of these armoured prehistoric fish, or gaze at the Pleistocene invertebrate and vertebrate fossils from the Errol Clay Formation through the reflective glass and imagine – for a moment – you are witnessing them swimming under the dappling surface of the primordial river.

Back in the Cononish I watch as scales slide and interlock, the smolt’s young body rippling muscle, and imagine tectonic plates sliding, molten rock buckling, boiling lavas flowing. In the blink of an eye, it is gone. Three hundred and eighty million years ago some fish began the long transition where fins started morphing into limbs, swim bladders to lungs.

Dart forward from the primordial and the river we recognise as the Tay was winding east following the last Ice Age, but the sea it flowed into was radically different from the North Sea of today. Ten thousand years ago a landbridge connected the south-east mainland of these islands to continental Europe, and the Rhine and Thames formed a river delta flowing south-east into what is now the Channel. Doggerland occupied much of the area between what we now call Denmark and East Anglia, making a smaller North Sea look like a large estuary fed by a myriad of north European rivers, not least among them the Tay. Its firth, though, discharging its waters northwards rather than to the east.

*

The Tay begins on Ben Lui. But it is also beginning to the north. Hold up your left hand again, palm facing away from you. If the Tay is your index finger, your middle finger is the rivers Tummel and, towards the tip, the Garry.

Pulsing like an upland river, the early morning traffic on the A9 flows from single to dual carriageway and back again irregularly throughout its 270-mile length. The road joins Lowland and Highland Scotland, following the Earn, Tay, Tummel and Garry as they cut through that central massif of the country’s mountains. It is joined along its route by many tributary roads and for decades it has been notorious for the number of lives lost – impatient locals, tourists driving on the wrong side, people falling asleep at the wheel. The entire route, during the writing of this book, is in the process of being dualled.

Today, sunshine and showers break out intermittently all the way up the road. It’s that kind of transitional day when winter has ended but spring doesn’t really seem to have begun. I think of Noah on his ark: the rains have stopped but the flood waters haven’t started receding. Over the sign to the Noah’s Ark soft play centre, just outside Perth, a fragment of a rainbow – ‘watergaw’ in Scots – forms an arc. Fragments of the river’s story are glimpsed as I pass Beatrix Potter’s holiday home at Dalguise, peer down into the gorge as I fly over the Pass of Killiecrankie, catch sight of the waded anglers in the Tummel at Pitlochry, and, occasionally, the shadow of the current road’s predecessor, the old A9, runs beside this modern route.

An hour out of Perth I stop at the Drumochter Pass, just shy of its 1,500-foot summit. Routes for road, rail, cycle and electric pylons all squeeze in here, between the gap in the mountains, the watershed between rivers Garry and Truim, tributaries of the Tay and the Spey. Snow frequently lies in the pass and in the corries of the hills above well into spring, and often into summer, but mainly it is a wet place. The annual rainfall here is four feet. The hills are barren of trees or bushes. They are mottled with years of patchy muirburnt heather, varying in colour and tone depending on when they were last burnt or the season; grey scree landslides offer a contrast of texture, and today withering bog grasses are a wan sepia on a tiny strip of the flat valley floor along which a stream meanders. Some call these human-degraded Highland landscapes ‘wet desert’. Climb down from the current road to the old one below and you enter another world. Tarmac is nibbled by the chittering frost; it has cracks where the ice has melted and refrozen and melted and refrozen over this and many winters (and at this altitude, in spring, summer and autumn too). Mosses colonise the damp slits; lichens grow in the pure air; wind-blown seeds fall into the cracks, watered by all that rain. Though in the heart of the wet desert at the extremity of the Tay, there is a gradual, inexorable reclamation of the human-built environment by nature, tiny seed after tiny seed swelling under the old A9. This is how the human age will end. It is not the only ghost road. Just above hovers the spectre of General Wade’s eighteenth-century military road, unseen but, throughout these high lands, ever present.

The water flowing off the old road settles in the flat ground at the foot of the pass. It forms boggy pools that feed sphagnum and bog grass, or seeps, eventually, into the stream – the Allt Dubhaig – that slowly snakes its way round ziggurat mounds of glacial deposits. A soggy, wet half-land forms at the southern end of the pass, its surface dappled silver by a shaft of sunlight breaking through from the low cloud. Snowmelt, fog drip, evapotranspiration – the clouds are in a state of constant exchange with this water world that rises high to meet them. The waters from the surrounding hills – Meall an Dobharchain (‘the Sow of Atholl’), An Torc (‘the Boar of Badenoch’) – choose their paths to the sea, north to the Moray Firth, south to the Firth of Tay, snorting and snuffling their way through a moraine landscape more like Iceland than the flat fertility of the Flemish fields at the Firths; this is one of only two sites in Scotland that the subarctic Norwegian blue heather (Phyllodoce caerulea) grows. Here the Ice Age is still present.

The water flows down tracks cut out of the hillside to allow access by grouse shooters and deerstalkers, big business across Highland Tayside. There are growing calls among environmentalists to regulate such roadbuilding, which seems to be accelerating, one reason being that they speed up the flow of water off the land. Today the only cries are of invisible grouse, the males warming up for the spring mating with echoing ‘tuck, tucks’ sounding hollow in the mist. It is not only the birds that are keeping ready for the season ahead. Above the stream, suspended between two staves, a half-inch-thick steel plate swings suspended on a shiny metal chain – a forlornly bling decoration for a medallion man of the mountain. Beside it a disintegrating sheet of hardboard decorated with white circles like a giant nine-spotted domino. Both steel plate and white circles are peppered with bullet holes.

At each end of the pass north and south are huge vistas westwards. Your view is channelled down the steep mountainsides flanking Lochs Ericht and Garry, two of that series of long lochs stretching deep into the west that act as storage basins, filling the Tay, signature features of the catchment here in the Highlands. At the end of the Drumochter Pass, you pass under the Inverness to Perth railway line and come to a small dam, neither high nor long, that runs behind the village of Dalwhinnie. Bags of salt are stacked ready to melt ice on the walkway to briny liquid. On the lip of the dyke a tiny ringed plover – usually more at home on the beach than here in the centre of the Highlands – patrols with urgent steps. Either side of the dam are turbulent in-flows, so wild they are caged behind steel fences: the first cascades down the mountain behind, then is channelled down six concrete steps out into the loch; the second is collected from underground, run-off from the pass that is redirected into the loch in a constant foaming, bubbling cauldron of brown, cream and white water, snuffling and blowing like a trapped, harpooned whale. On the fence beside this boiling pot of ice-cold water, the first of many signs along the Tay’s catchment claiming ownership and informing you of what is and is not permitted: ‘Scottish Hydro/Danger No Bathing’.

The majority of the Tay’s catchment lies to the west. To the east, it runs close to the feet of high mountains that top it up from their short, steep streams until joined by the Tilt at Blair Atholl and, further south, the Isla.

At the southern end of the pass, the river Garry picks up speed, flowing out of its loch. Collecting the slow, ambling waters of the pass, it rushes with them into Glen Garry just as the slow, speed-limited road widens to a new stretch of dual carriageway and the traffic hurtles full throttle towards its ever diminishing future.

But winter here can slow even the fastest-flowing. Snow poles mark the route to keep the road safe, but snow gates testify that even the constant passage of gritters and snowploughs is sometimes not enough to keep the traffic moving. Look north and Inverness is a city that can be cut off, but change your perspective and it’s the southerners who are isolated. Life in the north is different, even in the digital age. It is still controlled by weather. In the upper catchments of the Tay, sometimes you just have to thole it until the thaw comes.

Beside the snow gates at Dalnaspidal, the Allt Coire Mhic-sith comes down from A’ Bhuidheanach Bheag. Below the hillsides of charred heather and exposed and deteriorating peat, the narrow floor of the deep, gouged corrie is strewn with small rocks, gravel silt and sand. At the end of the last Ice Age, about 12,000 years ago, an ice dam restrained the waters of a mountain loch here. When the proglacial lake melted, the moraine debris scoured parallel roads along the glen – dual carriageways. The stones continue to flow. An earth science study in the British Geological Survey archive describes how grit and pebbles from the riverbed of the Allt Dubhaig ranging in size from a tiny 15mm to 25cm move and disperse along the glens here, continuing a journey started long before humans ever travelled this landscape.

*

Moving along the glen at the foot of Ben Lui, with legs heavy as stones, Mark and I reclaim our bikes. As we cycled downhill to the car park at Dalrigh it was our own prehistory we were discussing. Passing behind the Tyndrum Hotel, we talk of our father Joe, who worked there in his student summer holidays. Glancing over at the cascading Cononish on our right, the small pools of white water transform in our blethering into dinner plates stacked on our father’s arm, serving tables sixty years ago.

This area, called Strathfillan, is another transitional place. Travellers by road and railway from Oban and the west curve round the side of Ben Lui to Tyndrum. There they meet those making the journey from Fort William, Glen Coe and Rannoch Moor in the north. Passing Dalrigh together along the rivers Cononish and Fillan, they come to Crianlarich and diverge again, south to Glen Falloch, Loch Lomond and Glasgow, or eastwards along Glen Dochart to Killin and Loch Tay. Along these routes, countless travellers have passed for millennia. They have been looked after in croft and byre, priory and castle, inn and hotel. The names of a very few stand out from the anonymous flow. At the car park the information board explains that Dalrigh means ‘the field of the king’ in Gaelic, the king in question being Robert the Bruce. But this was not a field of glorious victory but the site of a brutal massacre of his small band of supporters long before he ascended the Scottish throne. In the literally cut-throat struggle for kingship, Bruce and his troops were defeated by Clan MacDougall here in 1306. Axes were used against men and horses, brandished steel ripped flesh, swords slit, kerns and gallowglasses were unseamed from nave to chaps, blood flowed. The future king barely escaped this boggy field with his life.

Beneath the battlefield the Cononish is joined by the river flowing north out of the glen between two mountains, Ben Dubhchraig and Fiarach, and together they become the Fillan, which gives its name to the whole area around here.

In winter this far north, daylight is a commodity as valuable as silver. On many of our hillwalks my brother, myself and our Munro-bagging friends have stayed overnight in Strathfillan to give us as early a start on the northern hills as possible. On the banks of the Fillan at Ewich, between Dalrigh and Crianlarich, the wooden ‘wigwams’ have provided the perfect overnight shelter for six to eight middle-aged men and large amounts of liquid refreshment. The Fillan, along with road, rail and West Highland Way, cuts through a narrow green valley floor hummocked by glacial mounds that give the landscape here a strange, otherworldly feel. The wet mossy environment absorbs and softens sounds. Mists can cocoon this glen, yet when the sun comes out and the clouds lift, the panorama of the high mountains to the south is one of the most stunning in Scotland. Ben More, Stob Binnein, Cruach Àrdrain – all hills we climbed – and at their feet Crianlarich.

At its elevated station, the four-coached trains from the south split in two and those from the north and west reconnect. While this is engineered, take a break in the station tearoom. Walkers are welcome. In summer, under the Victorian canopy, a pair of housemartins – travellers from the far south – have constructed a pot of a nest. In blue livery that matches the trains, they never rest, constantly swooping in and out to fill their insatiable chicks’ open beaks. The cream-and-green-painted iron rail bridge over the Fillan just beyond the station is one of the most beautiful on the West Highland Line. Under the viaduct, inches over the water, the housemartins’ sandy-coloured cousins swoop. Fish rise for the same flies rippling the smooth tawny surface. White clouds, and clouds of white riverside meadowsweet, are reflected in its surface. Pale purple hairbells, green willow and silver birch line its banks. A fallow deer bounds like a hare at the sound of squelching footsteps. Over a burn that feeds the river a fallen silver birch is a living bridge painted cream and green by lichens and mosses that thrive here in the pure West Highland air. High up in its vertical neighbour a heronry booms to the big bird’s call. Higher still, above the green tubes of newly planted tree protectors in the clear felled hillside, a buzzard circles. A sheet of rain clouds the lower slopes of the massive Ben More yet the undulating ridges of its neighbour, Cruach Àrdrain, are clearly etched against the sky.

I think back to previous seasons by this water, some of them crystal clear, etched on my memory, others cloudy, indistinct. Fishing on a hot June evening, the only things we pulled from the water being our cooled tins of beer. Seven of us crammed into one of the wooden huts at Ewich, the night before a hillwalk. Gazing up at a river of stars over Cruach Àrdrain at 2 a.m. on a January night, clouds of steam rising as I piss out a stream of the evening’s beer in the minus-five night, then waking in the morning to find the weather so atrocious we have to abandon the idea of climbing and go for a walk along the river instead.

The Fillan takes its name from an evangelising holy man who brought Christianity from the west around the year AD 700. There was a priory named after him here, and a handbell and crozier said to have been his are in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. There is also a pool in the river associated with him. Baptism is one of the seven sacraments of the Church. Christ himself was baptised in the river Jordan, so those converted by St Fillan mimic this physical manifestation of a spiritual cleansing. But the pool also retains some of its pre-Christian use – a use that is physical rather than spiritual. It is said to have healing qualities, though ritual must be followed:

. . . in order that the cure should be effective, the afflicted were taken to the riverside towards the end of the moon’s first quarter. Where a rocky point projects into the river, men were plunged into the water on one side and women on the other. The patients were then required to gather nine stones from the river-bed and on coming out to go to the top of the rock, 20 feet in height, and to walk three times round three heaps of stones, the accumulations of countless dippings. It was necessary after each turn to deposit on each heap one of the stones from the river-bed. After this ceremony, the devotees proceeded to the ruins of St Fillan’s Chapel, about a mile away to the east of their immersion. Here they were tied to a great stone with a large hole it in, and the ancient bronze bell of St Fillan was placed for an instant upon their heads. The patient was left in the ruins all night long, and if in the morning he was found to be free from his bonds, a cure was deemed to have taken place.

Six iron links of the chain by which the afflicted were attached to the stone survive in the Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum. Kill or cure? Robert Heron, travelling through Scotland in 1792, notes that if ‘the patient . . . is still bound, his cure remains doubtful. It sometimes happens that death relieves him during his confinement from the troubles of life.’

St Fillan’s Priory was destroyed by iconoclasts during the Reformation, but still people held on to elements of pre-Reformation – or in this case probably even pre-Christian – practices. The belief in curative properties of water and the clearing of evil spirits by the ringing of bells survives on the fringes of society into the modern era. While cures were gradually discovered for physical ailments, treatments for mental illness were less forthcoming. This led to traditional methods like those described above being practised and recorded.

These beliefs extend beyond the Tay and Western culture. Reading Dandelions by Japanese novelist Yasunari Kawabata recently, I came across a passage describing a temple converted to an asylum that allows the patients turns at ringing the daily bell. The doctor explains that the deep resonance of the bell ‘carries beyond the clinic . . . reminding the world that they’re here – they exist’.

*

Across the Tay’s catchment the bones of animals now extinct have been found – elk, wild ox, brown bear, lynx and wolf. These creatures were driven from this landscape by us over the 9,000 years since we began to colonise the banks of the river. Just as St Fillan and his evangelists drove out all but a tiny fragment of our knowledge of pre-Christian religion, so too do we know very little of the first 3,000 years of people living here. Foragers, gatherers, hunters, trappers, fishers: we left few traces of our existence except the charcoal remains of campfires, the flakes of our stone-blade chipping.

Some historians’ current thinking is that 50–60 per cent of the post-glacial land was by the late Mesolithic period covered in woodland, perhaps permanent closed forest in some places and in others grazed cyclically at the edges by large herbivores. For thousands of years, they believe, humans had little impact on this dynamic woodland, taking only seasonal fruits, animals in the hunt and wood for fuel. Even as humans began to herd livestock they still only used the Tayside forests for shelter for themselves and their beasts, its plants for dying wool, bark for tanning leather. Other historians argue that early humans had a distinct impact on this forest: using fire to clear grassy spaces among the trees, making spaces attractive to grazing herbivores, providing clear lines of sight for a spear thrower or predictable spots to hide traps. These clearings later became the model for places to graze their own semi-domesticated beasts. A strong awareness of seasonality and how to subsist using only naturally available resources sustained these Stone Age peoples. We must assume that they used the rivers and lochs in the same way as they did the forest: by taking gratefully what the waters naturally provided. Perhaps building as well various forms of fishing platforms, setting traps and nets for fish returning to shallow waters to spawn, netting seabirds nesting off the cliffs at the Firth, positioning hiding places along the banks where animals crossed, beside waterfowl landing lines among its reedbeds. Ancient fishing weirs were constructed using stones to build underwater walls or by planting wooden stakes in the riverbed and weaving poles or branches horizontally to trap fish, techniques that carried down to recent historical times. In Scots, ‘garth’ is an enclosure, usually fenced but also a shingle bank on a river, a fishing weir. A 1609 Act of the Scottish Parliament noted ‘All & haill the salmond fischeing . . . comprehending the garthis and pullis vnder-writtin’. Evidence of fishing weirs exist now only in place-names, such as Inchgarth (‘fish weir island’ ).

A Mesolithic harpoon head with two barbs in the National Museum of Scotland has been fashioned from an animal’s rib. Closeness to the natural world, a vital dependence on understanding its movements, moods and seasons, allowed our hunter-gatherer ancestors to survive either part or the whole of the year here. What they knew of living off this land, how they interacted with it, and what they believed remains a mystery. As tempting as it is to align our present-day concerns of climate emergency and the breakdown of humanity’s relationship with nature to some sort of imagined ethical ‘one-ness’ with nature of the earliest humans to inhabit Tayside, to wish that there once existed a golden age in our relationship with the natural world is unrealistic. As historian T. C. Smout writes, we ‘cannot make assumptions . . . however tempting, about the ideology of those who lived too long ago and with too ephemeral a material culture to leave any trace of their belief systems’.

What we can say is that Taysiders then killed beasts, birds and fish, herded animals and managed these lands and waters for their own benefit as we still do today.

*

The mountain is the source of the river. Melting ice transports its stones. The river polishes them. High in the glens, deep in the west Central Highlands, they are collected by human hands and revered.