2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

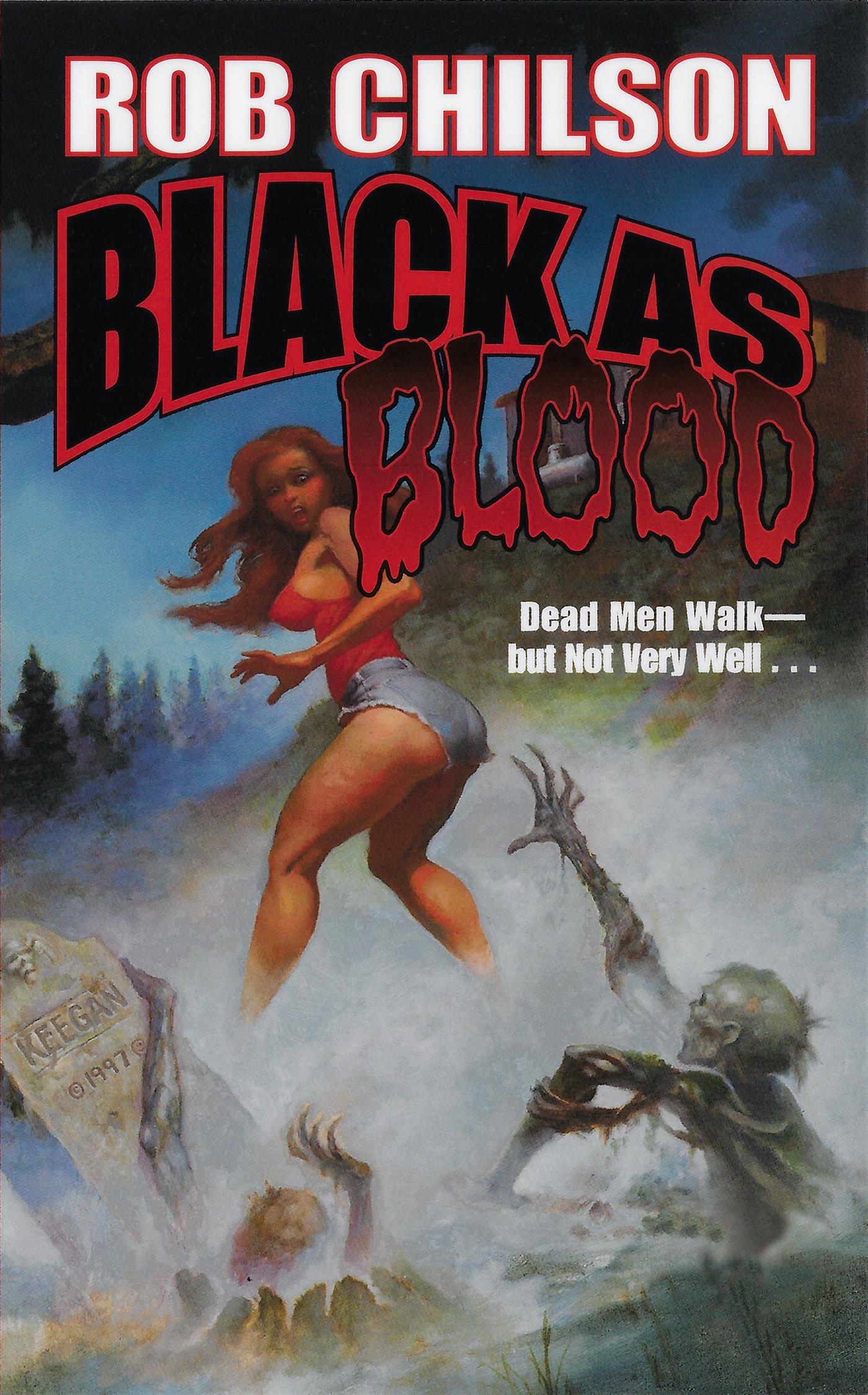

- Herausgeber: Boruma Publishing

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

The human race has split into two groups: ordinary people like Race and his mother and sister, and the Starlings, humans with godlike telekinetic powers. Their powers enable them to carry spaceships to the stars and settle many planets, while ordinary folk are no better than slaves. Now Race finds that he has Starling powers, too.

~~~~~ Excerpt ~~~~~

First correction to his visualization: there was no stream of traffic. He saw and sensed three or four ships; as many more might be out of his range.

They were running right into Slavin’s trap. His stomach lighter and more hollow with fear, he extended his mind, enfolding the fast little freighter within it, moving it as he had moved Dinine between stars. No acceleration was felt within the ship; instead, they felt Jacarantha’s grip weakening, draining away. Race crowded the safety limit, the air-speed indicator whining.

The transponder beeped in warning before they were out of atmosphere and Race felt a wave of despair. It was off, not replying to that insistent question from space. But where radar probed, coherent light beams also would be. The yellow sky had long since turned green, then blue; now, royal purple set with stars.

The transponder carilloned and the radio barked at him harshly on the official space frequency: “Attention freighter, halt at once or—”

Another voice cut in as authoritatively, but Race wasn’t listening. From low, fast orbit overhead a ship had flashed up behind him; he felt it swell. A fast-moving dot before him would be another. He was keyed up intolerably and turned the ship now without a thought.

At his right hand was a handle in the hull. Moving it swiveled a tele-periscope that combined a low-powered wide-angle view with a high-powered narrow-angle one. Immediately below their line of sight and precisely parallel to it was a glass tube about an inch in diameter and five inches long. Connected to it was a pocket in the hull, containing a handful of common glass marbles. The whole apparatus was outside the airseal.

It was the work of but a moment to line the telescope and tube on the growing dot of light that was the first ship. He had placed marbles at the bases of the firing ports before takeoff, and now he flicked one as he had flicked pebbles like bullets in the Mountains of the Oroné months before, but with the fury of despair.

Involuntarily he blinked — in time to save his vision.

The Starling ship erupted in a fireball that illuminated half the world below. For half a second Race stared horrified at the destruction he had wrought. Then fear blossomed like that spreading glare: every Starling in the area knew where he was now. He swerved the ship away recklessly, not hearing the clangor of the radiation alarm.

His mind swooped and reeled as things like planets whipped past in less than an eyeblink — two of them, almost on opposite sides of the ship, one nearer than the other. On the radio two voices were bellowing, one, “Surrender!”, the other, “Shoot! Shoot!”

Another thing flicked past, invisible, undetectable but to his mind — seeming to have planetary mass yet to be incredibly tiny. Marbles like his own, flicked at near light speed.

Fear galvanized him. His rolling gaze touched the Imperial Cluster and in a moment the ship was in incredible motion toward it. Jacarantha shrank behind them.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

The Star-Crowned Kings

by

Rob Chilson

Copyright 1975 by Rob Chilson

Previous publication, DAW Books 1975, 1981

Israeli edition 1982 (Elisha ben Mordekai)

Artwork by Linda Cappel

Chapter 1

Race gasped.

The flagstone before the cottage door had lifted obediently into the air some four inches — to the height it should have had above the grass. Race was vaguely conscious of a quivering tension within him. His mounting fear broke in that gasp and the tension broke with it: the flagstone fell back with a faint sound. Race lifted a white face to his mother’s.

“What happened?” she asked sharply.

“Th-the flagstone ... raised up.... ” His voice was a croak.

Janinda Worden stepped to the open half-door and looked down at it, a tiny frown between her brows. She was still slim and youthful and attractive, her face as now usually serious. There was fresh black earth about the edges of the flagstone and the grass blades had been bent outwards on all sides.

“Come inside.” Janinda glanced left, then right, at the empty street of Ravenham. The village was as quiet as usual.

“Tell me about it.”

Race was still in shock; he seated himself lest his legs give way. “Well, you know, we’ve always wanted that flag lifted, and I just looked at it and wished it was higher, like I’ve done a — a hundred times, and — and—”

The stone was too low, and ever since he had stepped into a puddle almost ankle deep over it, it had irritated him. But it was so big that it would take the three of them to lift it — or more. So they hadnever gotten around to raising it. It hardly seemed to matter; life was placid in Ravenham.

Janinda was different from the rest of the villagers.

She had gone through youth, marriage, childbirth, and widowhood without much change in her matter-of-fact demeanor, but there was something more than mere placidity within her. That was comforting just now. To Race’s relief his mother accepted his statement as calmly as she accepted everything.

“Could you do it again?”

Icy fingers plunged into his belly. “I — I don’tknow.” Race felt that he had turned white.

Janinda did not press him. After a thoughtful moment she said, “All right, we won’t discuss it any more, for the moment. —Don’t tell Joss about it — or anyone else, naturally. It’s not at all impossible, you know,” she said gently.

Race gulped, nodded, if anything more frightened than before. All his short life he had known of Starlings. They could, and routinely did, move mountains by their thoughts alone. Working together, they could and had moved planets. They alone could propel starships across the galaxy and hence deserved the name Starling — children, dwellers, of the stars.

They were the god-like figures who dwelt in the Spires they raised, who crossed the sky occasionally in the gleaming cars they moved with their minds, distant bright points of awe, who ruled Mavia and Sonissa and the Imperial Cluster, and all the stars back to legendary Earth from which they all sprang, human and Starling. Their rule was iron, their will law, their whim death or wealth to the mere humans who orbited about them.

Race retired to his room in a daze. Two emotions warred in him. One was fear. He imagined himself the butt of his schoolmates — how they would laugh that anyone from Ravenham, especially a Worden, could be a Starling! — and of course it couldn’t be true. No, better never mentioned. Then in a breath he imagined himself confronting a scornful-eyed, imperious Starling with a crown on his head, trying to gain admittance to their society. From the expression on the Starling’s face, never.... His comfortable life was torn apart and nowhere could he turn.

The other emotion was elation. While his fears rose and fell so did exultation. He saw himself flying above his worshipful schoolmates, saw himself raising his own Spire, dressing his mother and sister in gold-shot glass, building his own ship and plunging into the galaxy beyond the Cluster....

Jocela Worden laughed at her brother when Race dragged himself to the table. The shadows were long outside, the air slightly cooler, with a hint of the evening’s dew. It had been the longest afternoon of his life.

“You shouldn’t have been in such a hurry to grow up,” Joss said mischievously. “If you think you’re tired now, wait till harvest!”

Race had recently gone to work under Keithly in the great grassfields served by Ravenham: the village was a proprietary one, one of many on the S. (Starling) Oroné plantation. The fields were the destiny of most of Ravenham youth, those who could not escape to Fulvia or some other town. But though the work on the big tractors was tiring, it was not enough to make him sleep all afternoon.

Joss attacked a meager portion of fruit salad and slanted her impish eyes at him. “Or was it an interview with Else Hann that sent you to bed? I could’ve told you a week ago she was going to Paulfields with Joe Gippert....”

Jocela was almost two years younger than he. Race got no help from his mother. But she was not smiling faintly at their banter, as she usually did.

“How do you like your job with Keithly?” she asked. He had been driving a tractor for two weeks now and she had had sense enough not to ask that. Race looked at her, wondering what could be behind the question. “All right, I guess. It sure cuts into my time.”

Five and one-half days a week, ten hours a full day, he drove a monstrous steam tractor pulling a six-bottom gangplow across the bright green fields, turning the tall grass into — not under — the rich soil, to make it yet richer for the next crop of grass. All summer he expected to be driving the same tractor, now cutting the grass to be baled or pickled as ensilage. The protein-rich green gold was the starting point for a whole series of syntheses, some of them taking place in animal bodies, some in great vats full of bacteria or algae. Milk, meat, wool, horn and a half a dozen other organic products came from it directly; converting it would produce food for a thousand strains of bacteria and algae that further produced hundreds of raw materials or finished products — ultimately it would end up as paper, plastics, clothing, even food.

The great fields literally extended over the rim of the planet; Ravenham set in its little private forest was an island lost in a green sea broken only here and there by the rocks of tractor and implement sheds. To a man working across them on even the tallest machine, they seemed endless. They literally were endless. Race would doubtless spend his life plowing and mowing them, hours looking toward the green/green horizon over an orange-painted hood, to die and be burned and scattered over them in the end.

For all its beauty, for all its placidity, Ravenham was a place of desolation and desperation.

“How does Keithly treat you?”

“Well enough, I guess.”

Sometimes when the black-bearded foreman looked at him, Race thought he was mad — driven insane by the endless green plain, by the endless barren vista of life. A gruff, sullen, short-spoken sort, who seemed to like him not at all; but Keithly liked no one so far as Race could tell.

“He has you up on a tractor?”

Race nodded. Few instructions were needed, he had learned all he needed to know the first day, except how to tell his way about the fields. He had felt honored and been proud to say that he was driving. He greatly preferred it to the sheds and shops where he was directly under Keithly’s eye and among the other older men, though he might pick up a trade there. But he knew what she meant. Officially he was still an Apprentice — at one-third the pay of a full Operator — though doing the latter’s work.

“Plowing is easy — but cutting and baling and all take more skill. Likely he’ll put the men on that and pull me back to the sheds.” To learn a trade.

“Not likely,” said Joss coolly. “He’ll keep you on as Operator all your life — at Apprentice’s pay as long as he can.”

Race shifted, half-angry. “Why would he do that?” he said, trying to argue himself out of the same opinion. “It’s no money in his pocket.” Payment was by computer; Keithly couldn’t quietly promote him to full Operator, without telling him, in order to pocket the difference.

“May not be Keith’s doing at all — maybe the Plantation has all the Techs it needs. But Keithly will keep you an Apprentice the full year just on general principles.” Joss could be unpleasantly intelligent at times.

Janinda said, “Some men are that way — even some women. They resent younger people just because they are younger. They don’t like to realize that some day they’ll be dead, and youngsters they’ve bawled out as dirty-faced boys will be as important as they ever were.”

That remark illuminated Keithly’s character like a lightning flash. Race put down his spoon slowly, feeling the horizons closing in around him. He had considered Ravenham lightly when thinking of his future. Without much thought he had long ago decided that he would be one of the lucky few who escaped to Fulvia, or even to one of the cities; in his favorite daydreams he got a job on a spaceship — a starship — even became a favorite of a Starling.

In his earlier daydreams the Starling had been a wise older man not unlike the father Race could barely remember. Nowadays she was usually a beautiful young girl, spoiled but admiring his homely wisdom.

Now, for the first time it hit home that he would probably spend the rest of his life in this house and the fields around. For excitement, the usual holidays and maybe a trip to Fulvia once a year. The tractor Race drove: it was far older than he, yet he could spend the rest of a long life driving it, and his grandson could make a good start in life on it. The big steamers rarely wore out. Ravenham was a trap that had caught him, despite all his dreams.

“It’s no place to bring up children — the Plantation,” said Janinda unexpectedly. “I tried to get your father to leave, long ago.”

Joss was amazed. “With a wife? You’d have starved! What chance would he have of being hired by the Transport Company?”

“No worse than anyone’s — hardly any, that is. It would have been hard on both of us. I’ve always blamed myself for ruining his life.”

They could only stare at her. Janinda had never talked this way before. She looked a little past them, her face seeming soft even in the harsh glare of the fluorescent light.

“He would have left Ravenham, like his uncle did, if he hadn’t fallen in love with me. But he was afraid that if he left, he’d never make it back — he knew I’d wait for him as long as necessary, it wasn’t that he was afraid of. But you go where the Company sends you, and the best-paying jobs are mobile. And Jayce was an impatient young man, more so than most — wanting to leave was a fire in him. He couldn’t wait to be married, either. I gave in — I was young too — but I was afraid all along it was a mistake.”

She sighed. “Then we were married and he didn’t dare take the chance — even the lucky ones sometimes have to wait months for an opening. Then you were on the way, Race, and your father began to lose hope. We thought — he thought — that the Transport Company wasn’t the only way out of Ravenham. There are the Plantation factories, for instance. But they are so far away — and we both had gotten old enough to lose faith in miracles. We probably wouldn’t have had a chance. I told him I’d follow wherever he went and never blame him however bad things were, but he saw too clearly that it was hopeless.

“Can anyone blame him for drinking too much at times? I never did. He wasn’t a regular drunk, it was only every couple of weeks, and he never so much as raised his voice to me. It never interfered with his work. He hadn’t been drinking the night before he fell off his tractor. He wasn’t hungover that morning, and he never drank on the job.” She paused for a long time.

“He would never have gone off and left me — intentionally. Yet, I imagine he must have greeted the plowshares with relief.” There was a long silence. Race and Jocela looked at each other soberly.

“When he died I swore I would escape with you both, if it meant all three of us jumping into the canal.” Janinda looked into their astonished faces. “I think it’s now time to leave.”

Race’s heart leaped, stirred by the story. In the closed society of Ravenham the facts had long been known to him. But he had never heard his mother’s account of it and had not had the wit to see the facts from her viewpoint. Jayce Worden had been a wild young man who ended as could be expected: what else, in anyone so mad as to want to leave Ravenham? Race had resented that, but not consciously enough to re-examine the story. Now he was thrilled by the idea of escape as a fitting last act to that (he now saw) romance. Then the uncertainties took over.

For the well-behaved (were there any others?), life in Ravenham was as secure as could well be imagined. At no time was food short. Though there was little money, still less was the opportunity to spend it. Steady work and congenial homes were theirs by right of birth.

The Oroné were mild masters. The proprietary villagers were not well-paid, but neither were they overtaxed; a small charge for the houses was all. Involuntary projects were unknown on the Plantation. In three generations no Starling had been to Ravenham, and that had been for a ten-minute visit. There was no fear of the whims of their masters. No human overlords squatted in their Great Chairs of Justice in the square. No leather-clad patrols roamed the streets. No extortion squads harried the fortunate into dungeons. No assassins marked off the potential troublemakers.

The Plantation villages were beautifully designed.

Huge old trees shaded the old houses, the latter seeming as solid, and solidly rooted, as the former. Stone and brick, with heavy slate or stone-slab roofs, built to last forever and having made a good start on it — Ravenham was picturesque with well-built age and moss and flowering vines over the brick and stone, the great trees over all. On the south, from whence came the shearing winds of winter, was a solid belt of cedars. The village faced north, toward the distant blue line of the Mountains of the Oroné.

Comfortable houses, garden fields, community barns, a meeting house, local self-government which the foremen and Plantation overseers were not permitted to dominate: they were as well cared for as prize cattle.

To leave Ravenham would mean going to Fulvia — a quiet canal-port, living mostly on the export of grass and grass products, but a fast, dangerous city to the villagers. Here, with what money they had accumulated, they would live until, somehow, a job was found. And in Fulvia the only source of jobs was the Transport Company — there was not even a row of dives. Towns like Fulvia were common in Plantation country; not every tenth one was big enough to interest the mariners of the canals.

“A woman alone would have no chance,” said Janinda quietly. “It would mean a job in a private home — and even in Fulvia, that could mean anything. Saved-up money would not last long — prices are high there, and wages low here. I have some. Very little.”

That was understandable. Joss stirred resentfully.

“They should have done better by you! I would by my daughter, even if I couldn’t stand her.”

Janinda’s decision to marry one of the wild Wordens had dismayed her stolid family. Jayce was the worst of all. Didn’t everyone know how wildly he talked of leaving? And didn’t everyone know what happened to people who left? Why, not one in ten was ever heard of again! And them as came back were never good for anything again.

The result was the virtual disinheritance of Janinda.

Her family could have gotten her a good job with the Plantation in Administration or Accounting — the Sturtevants were an old, large, respectable family in the village. The best she had been able to get was a minor job in Accounting — tallyman. That because of the tradition that all be cared for. Of advancement there was no chance.

As a widow with children, the Oroné permitted her the house for but two-thirds the usual charge, deducted from her pay by the computers in Plantcontrol. But in the early years, when the little family had had no one to hoe in the communal fields, she had to buy all their food. She could not have been saving money for as long as ten years.

“It was almost worth being dropped, not to be preached at,” said Janinda coolly. Race grinned a little; his friends were always being lectured by parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, uncles, aunts, great-uncles, great-aunts — and friends of all these. He was a wild Worden boy and came in for comparatively little lecturing, but much head-shaking.

“But how long can we live in Fulvia on it? Or—” Joss caught her breath— “can we take passage to Junction City?”

“I doubt it, three of us? No. I’ve had years to think, though. I think we should go north.”

They caught their breath. The S. Oroné Plantation was a broad valley, over sixty miles wide, oriented from northwest to southeast. At the south was a range of old hills, the stubble of a mountain range; to the north, a range of mountains parallel to it. The valley, once quite hilly and varied, had been leveled by the Oroné into a rolling, nearly flat floor a hundred and fifty years ago. The river that had flowed through it had been straightened and its drop lessened, to give it the gentlest of flows, so that the barges should not have to battle a strong current. The valley’s length was about four times its width and the river, at Ravenham, was about forty miles from the Mountains of the Oroné to the north, twenty from the hills to the south.

Since Ravenham was but ten or twelve miles from the river — near enough to make trips to Fulvia possible — they were some thirty miles from the mountains.

“How could we live in the mountains?” Jocela’s voice was hoarse.

“We have your grandfather’s rifle and a good supply of shells. And Race is a pretty good shot.” Wild animals grazed the grasslands and the Plantation encouraged their hunting. “We can raise a small garden — I’ve been accumulating seeds. We’ll make out. How long it will take to cross them we can’t know. And no one knows what’s on the other side.”

Mavia did not waste communication channels on the entertainment or education of mere humans. On the Plantation they had no certain means of learning of distant lands.

Janinda stood up briskly. “I hadn’t intended to leave for, oh, nearly a month. It’ll still be chilly in the mountains. But now, I think we’d better leave tomorrow.” She looked at Race.

Chapter 2

Race lay awake long that night. He felt as the sod must feel when the plow comes and stands it on end, one edge to the sky, the green tops on one side and the cut roots on the other. All in one day had come a shake-up such as few of Ravenham’s placid people experienced in all their lives. And it came as he was still adjusting himself to the life of an equipment Operator on the great green fields.

In the cozy feelings of the dinner table and the later talk, he had forgotten about the movement of the flagstone. His mother’s words brought it all back again, and now that he had time to rest after the excitement of packing he almost trembled at the possibilities.

As was her habit, Janinda had come to bid him goodnight. “Race? We’ll not tell Joss about you until we’re in the mountains. Not that I think she can’t keep a secret — but she’ll have enough to think about. And we don’t know if it means anything.”

“All right. I’d just as soon not talk about it — it sounds so ... weird.”

“I don’t think she’d laugh, even if you can’t do it again. That’s another reason for going to the mountains.”

“To have room to practice — yes. I hadn’t thought of that.”

Practice! Why, Janinda must really believe he could do it! Long he lay awake, now believing, now despairing; now hoping it was true, now fearing that it was.

The next morning was Sunday. The Wordens were up by first faint light, an hour before the sun. Already the village was beginning to stir. Church service was held on Sunday, for the less than half who attended on any given Sunday. Religion was not an important part of such monotonous lives as these; men who worked six days a week saw nothing wrong in taking a frequent Sunday to hunt, fish, or go on a short trip. They would have company on the road.

Race carried the rifle and a supply of shells.

All three had packs of food and blankets wrapped in tarpaulins — discarded implement covers, common in the villages. A few cooking utensils completed their outfit, and clothes. Race felt obscurely ashamed to be carrying so much more than the usual pleasure-seekers, and Janinda appeared to share this feeling; she was anxious to be off.

They were the first out of the village. It seemed much lighter, out from under the great trees; then it seemed immensely daunting. The road seemed both endless and deadly monotonous. Overhead, the Imperial Cluster had long since set, but other stars were still visible. They faded as Ravenham shrank behind them.

The road was hard-packed gravel; the usual traffic was steam tractors pulling trailer-loads of hay and silage out, and manure coming in. Rides could be hitched on weekdays, but there was no specific passenger traffic; no tractor traffic at all on Sunday.

The sky turned from gray-black to deep blue to deep green. Then the sun began to rise behind them, and as the world brightened the sky began to assume its normal apple-green, a deeper color near the zenith. It looked yellow around the sun, and when Race looked back at Ravenham, southeast of them, he saw it as a dark green blot against the dazzle of yellow, set in the rich light green of the fields.

None felt like speaking. They marched in a grass-green circle bisected by the brown road, under a sky-green dome. No other road was visible from this angle — the grass was shoulder high. Little by little, Ravenham dropped below the curve of the planet. The only break in the monotony was the colorful specks of travelers far behind them in the road.

At length — some three hours of steady walking — Paulfields loomed up before them. This was a larger village but otherwise quite like Ravenham, fronting on a transverse canal and serving as a shipping point for half a dozen villages. To it they shipped the grass they raised; from it they got back manure and such food, tools, and manufactured items as they could not produce themselves, plus tractor fuel. The Wordens were reasonably familiar with Paulfields, had friends and even relatives here.

Now they avoided the canal-front center of the village, where they might meet people they knew, swinging north around the edge of the village to the canal above it.

“Wow!” said Jocela in relief, dropping her pack and throwing herself down in the shade. “I never knew blankets were so heavy.”

“I’m hungry.”

“It might be better to go easy on the food,” said Janinda expressionlessly. “It may have to last us a long time.”

That made them feel twice as hungry, but both of her children stared at her in awe. No one ever had to economize on food; the necessity of rationing it had never occurred to them.

The transverse canal made a double slash of shade across the endless fields. Both sides were lined with trees, now quite old and huge. It was a placid stream. Like the river it emptied into, it was designed to minimize fall and current speed; one of many graded and regulated tributaries coming down from the mountains or up from the southern hills. Like the river, these canals were string-straight and were controlled by dams at their heads. The grass fields were so skillfully managed that they had little runoff, and that seeped evenly into the canals — there were no streams winding through the fields.

On the water side of the trees, on each side of the canal, was a stone-slab road — typical Starling make. Each slab was yards thick and usually more than a hundred feet long; a mountain had been sliced into chips to make a road. The joints between chips, however, were frequently several inches wide. The Starlings had not patience for careful work, though in their defense it might be said that there were thousands of miles of such roads in the Plantation.

Now the occasional fishermen pulled in their lines and stepped back across the road; the Wordens heard the ding-a-ling of bells. A barge train came nosing past the town, pulled by an electric locomotive on the canal road. The Wordens gathered up their packs without haste; this was a familiar sight to them. The locomotive’s brave scarlet and violet paint was dingy close up, but it was massive enough to be impressive. The Operator looked languidly at them. Its speed was a little faster than a walk.

Behind came the lead barge, covered. The next barge was silage, also covered. Then another, and another, of the special silo barges. Finally a barge-load of hay. It was early for hay; even the silage was only just being brought in. But hay went upstream all the time — there were a dozen barges of it behind this one.

Janinda led them across the grooved road — the rubber tires of the engines had cut the grooves too deep in their century and a half of operation, so the bottoms of the grooves had been repaved with cobblestones — and down to the edge of the canal. Joss leaped for the barge-load, clutching the timbers of the rack with a laugh. Race followed. His baggage hampered him more than he had thought, and the rifle got in his way. Janinda prudently seized a rack timber and stepped down onto the front fender wheel.

The right bank was always the near bank, whichever way you faced, so that the barges needed wheels on but one side to fend them off the canal side. These were about two feet in diameter, rubber-tired. Each horizontal fender wheel was covered with a wooden shield; too many people had been injured stepping onto the hub.

It would take an impossible number of guards to prevent such joyrides, so neither the Plantation authorities nor the Transport Company tried it. No one on the banks paid any attention to the Wordens.

Joss and Race clambered rapidly up the towering load, to the top of the timber rack, on up the pyramid of five-hundred-pound bales of hay. They dropped their packs with a sigh and looked eagerly around. The load was as big as a house, but was still overshadowed by the huge trees on the shore.

With a guilty start Race remembered his mother and started down to help her, but Janinda had reached the top of the rack and pulled herself easily and gracefully up despite her bundle and the umbrella. Atop the load she brushed her hair back, smiled and waved to a boy on the bank who was delighted to see a grown woman on a hayride, and looked around with pleasure.

“It’s been years since I went on a joyride. I had almost forgotten what it was like.”

“Don’t you just love it in spring?” Joss asked eagerly.

“Yes, or in early winter when the banks are full again and it’s not too cold.”

“This breeze is nice, and we won’t need the umbrella for hours yet.”

The sensation of steady if slow movement was irresistible, so rarely did they ride a powered vehicle. Race would have been entranced even if he were not used to his tractor, though it went faster than this, twice as fast with a full gangplow. The faint hum of the distant locomotive was all but drowned by the lap of the waves between barge and bank; those were the only sounds. They knew that this motion would continue without a break to the head of the canal.

“We should be about halfway there by noon,” Janinda said.

Race looked at Joss; excitement lit their eyes. Surely nobody from Ravenham had gone more than halfway there; they had to allow time for the return journey, as the barge trains on the transverse canals did not run by night.

“The farthest I ever went was two hours up,” said Joss.

“Me too — to Moreton.”

Both had been downstream to Fulvia on the river several times, but didn’t care to mention it in their mother’s presence. She knew it though, and smiled in her way, as if to herself. No one went alone, and no group could keep a secret; mothers always knew. It was not usually forbidden, but everyone knew that it was better to stay away from the town, where village gossip had so little restraining influence.

Janinda opened her bundle, rolling the tarp out on the hay first, then the blanket and the two quilts; a bedspread on top. “I wish we had more sheets,” she murmured. Race wished for pillows.

Joss jabbed the folded umbrella into the hay, ready for use. It was twice as old as their mother — half as old as the Plantation, almost. Their grandmother had put a new tarpaulin cover on it about the time of their parents’ marriage, so it was still in fine shape, its gold and black hardly faded.

They all sat decorously for awhile, watching the endless fields passing by beyond the trees. Then Joss and Race got restless. They prowled over the load, shouted insults at friends they saw on barges behind, and went down to drink from the clear, cool canal. They swung off and ran ahead, to climb trees and drop on the load, and for awhile they played king of the mountain on the load, though neither could swim.

They sat dumb and decorous whenever they passed a village on their side of the canal, being warned in advance by the fishermen. At each village the locomotive climbed a stone bridge over the harbor entrance, paying out cable from the boom to the lead barge. Though the engine never slowed, this allowed the barges to do so. There was time for the villagers to leap aboard and unshackle the covered barges on the end. In midstream a steam tug awaited, with a line of new barges to be attached.

Race explained the system to Joss, though she understood it as well as he. “The main idea is never to stop the locomotives; constant stopping and starting is not good for their guts. You notice that they always break the train just after the hay and silo barges. That lets each village put its own grassers on with the rest. At each village we drop a line of covered barges and pick up a different line dropped by the previous train; the train that follows us will move our covered barges up to the next village.”

“Gee, thanks for telling me! I always wondered — if you knew. —It must take days for a covered barge to make it up the canal, except for the specials at the front end.” The specials went straight to the canal-head villages.

“Yes, but it doesn’t matter.”

The covered barges carried articles for the village stores, except the tankers of tractor fuel. They were also classified as “covered” for convenience, to distinguish them from the “grassers” of hay and silage, though the latter were also covered.

Presently several men stepped off the engine and were replaced by men waiting on the road. A village lay across the stream here. The barges jolted as the tail was cut out, jolted again as the tug pushed its train against them. They saw the locomotive crew leap onto the tug’s deck.

“What does that mean?”

Janinda looked at the sun. It was not yet quite overhead, but the band of shadow on the canal was quite narrow. Rays of sunlight were becoming frequent, stabbing down between limbs.

“I suppose it means we’re halfway from river to mountains, and the crew is changing off to ride back down to home.”

“Then these men— ” Joss gestured at the engine— “they’re from the mountains?”

“I suppose so.”

All three looked eagerly up the string-straight canal. The Mountains of the Oroné were much taller than they had ever realized, but as ghostly blue as ever.

“We’re still not halfway from home.”

At her words Race and Joss sighed. The trip was becoming monotonous, and the heat was yet to come. They felt shy about jumping off the barge under the noses of these mountain men, as if they might be ordered off the hay if they disturbed anyone. But the barge behind theirs had also acquired riders, and so had several others — all strangers.

“Imagine living here in the middle of the canal, where you don’t have time either to go down to Fulvia or up to the mountains on a trip,” said Joss.

The merrymakers behind them began to sing, and it startled them all to find that it was a perfectly familiar song.

“Going home must be more fun than coming up here — or up there, anyway,” Race said, pointing to the mountains.

“Why? Oh!”