Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

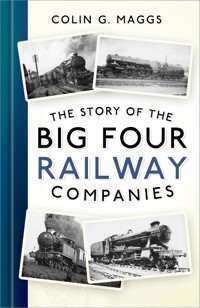

GWR, LMS, LNER and SR: these initials arouse memories of the Cornish Riviera Express, the streamlined Coronation Scot, the streamlined Coronation with its beaver tail, and the Southern Electrics, yet three of these companies only enjoyed a life of 25 years. Colin G. Maggs, one of the country's leading railway historians, tells the story of how these Big Four companies came into being and their enormous success following the rundown of the railways during the First World War. The remarkable, if surprisingly brief, era of the Big Four saw great changes and achievements, including streamlining, speed records, electrification, diesel power, railway-owned buses and aircraft, and a real sense of cooperation between companies. The Story of the Big Four Railway Companies is a memorable illustrated history of their reign.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 313

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Front cover illustrations, clockwise from top: K2 class 2-6-0 No 4685 Loch Treig (E.J.H. Hayward); Princess Coronation class 4-6-2 No 6230 Duchess of Buccleuch (Author’s collection); Frederick Hawksworth’s 1945 4-6-0 No 1000 County of Middlesex (Author’s collection); J1 class 4-6-2T No 325 heads the Pullman Brighton Belle (Author’s collection).

First published 2022

This paperback edition published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Colin G. Maggs, 2022, 2024

The right of Colin G. Maggs to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 229 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Note to the Reader

Acknowledgements

Foreword

1 Railway Companies before 1914

2 Railway Grouping

3 An Outline of the Main Pre-grouping Companies

4 The Great Western Railway

5 GWR Locomotive Development

6 GWR Principal Named Trains

7 The London, Midland & Scottish Railway

8 LMS Locomotive Development & Electrification

9 LMS Principal Named Trains

10 The London & North Eastern Railway

11 LNER Locomotive Development

12 LNER Principal Named Trains

13 The Southern Railway

14 SR Locomotive Development

15 Southern Electric

16 SR Principal Named Trains

17 The Big Five

18 The End of the Big Four

Appendices

Appendix 1 The Constituent and Subsidiary Companies

Appendix 2 Average Holding of Railway Shares, 1922

Appendix 3 1923 Statistics

Appendix 4 Staff Employed by Railway Companies of Great Britain during the Week Ending 25 March 1922

Appendix 5 Staff of the Big Four Employed on 24 March 1923

Appendix 6 Grades of Staff Employed by the Big Four during the Week Ending 25 March 1923

Appendix 7 Dividends on Shares of the Big Four Aspect

Appendix 8 Locomotive Stock of the Four Groups

Appendix 9 SR Electric Multiple Unit Codes

Bibliography

NOTE TO THE READER

Although this book is generally in chronological order, sometimes to avoid multiple short entries it has been deemed more useful to the reader to include the subsequent history of certain subjects.

Train times in the book are those given in official timetables, the 12-hour clock being used prior to June 1963.

When referring to travel to and from London, Up and Down have been given upper-case initials, while when referring to gradients the lower case is used.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Especial thanks are due to Colin Roberts for checking and improving the text.

FOREWORD

As a child brought up in the 1930s and 1940s, I’d always assumed that the GWR, LMS, LNER and SR had existed since time immemorial. I was puzzled by the fact that older people referred to the LMS station at Bath as the ‘Midland’ station. Adding to the perplexity was that an issue of the Meccano Magazine circa 1940 recounted that a railway enthusiast had spotted a second-hand copy of Twenty-Five Years with the LMS, bought it expecting to read of experiences on his favourite railway and then, when opening it, discovered to his chagrin that LMS in this instance stood for the London Missionary Society. The magazine’s editor observed that the gentleman should have realised that the railway LMS was less than 25 years old.

Unfortunately, no book such as the present volume was available to enlighten my knowledge of railway history and only over many years have I been able to build this fuller picture.

1

RAILWAY COMPANIES BEFORE 1914

Most of the British railway system was built by private companies. When a group of businessmen decided it would be a profitable enterprise to build a line from A to B, they immediately ran into the problem that the land belonged to others who might not welcome a railway.

This problem could be overcome by obtaining an Act of Parliament, which gave powers for compulsory purchase, and in the event of a dispute, the case could be settled by arbitration. Legislation was obtained either by a Private Act, or by a Local & Personal Act, and obtaining either was a lengthy and expensive business. The plan for a railway had to appear before committees of both Houses as a bill and might be rejected by either committee. If it succeeded in passing these hurdles, the bill then had to be passed by both Houses before receiving Royal Assent and becoming an Act. In addition to allowing a company to secure land, an Act permitted a company to raise or borrow, within stated limits, the capital required.

The world’s first public railway was the Surrey Iron Railway, its Act receiving Royal Assent on 21 May 1801 and the 9 miles from Croydon to Wandsworth opening for goods traffic on 26 July 1803; parts of the route are still used today by the London TramLink. The first passenger railway opened in 1807 to carry people from Oystermouth to Swansea.

Arguably the first railway to start the network of lines in Britain was the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, which opened on 15 September 1830. The next major railway to open was the Grand Junction linking the Liverpool & Manchester at Newton, later called Earlestown, through Warrington to Birmingham where it formed a junction with the London & Birmingham. In the late 1830s and 1840s railways expanded apace, running from London up the west and east coasts to Scotland and from the capital to the south coast, the west of England and Wales, serving all major towns and cities.

Smaller towns not served by railways often felt their trade would be improved by the construction of a track, so a group of industrialists would create a branch line, sometimes working it with their own locomotives and rolling stock, but often having it worked by a larger company. The latter method was generally more economical because requirements could vary: although perhaps one locomotive would normally suffice, a second would be required when the first was undergoing maintenance; and while perhaps two passenger coaches might normally be enough, on market or fair days extra vehicles would be required to handle the traffic. A larger company could handle such fluctuations better than a small company, which would not find it viable to lock up capital in stock only used occasionally. In due course many of these smaller railways, often run at a loss, were taken over by larger companies.

By 1914 railways covered most of Britain, only a few places being far from a line, and trains run by approximately 200 independent railway undertakings. All these companies had separate boards of directors and administrative staffs to work and maintain these undertakings, the majority of the investing public possessing holdings of £500 or less. The UK was greatly indebted to this private enterprise for a highly efficient transport organisation which contributed very largely to the communal prosperity of the nation by exporting coal and manufactured goods, and carrying imported raw material to factories.

So, with the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, there was ready at hand a military machine of the first importance. Under powers vested in the state by Section 16 of the Regulations of the Forces Act, 1871, the government took possession of practically all the country’s railways. The 1871 Act empowered the state to assume control of the railways in an emergency. This control was exercised under the authority of a warrant issued by the Secretary of State for War and had to be renewed weekly throughout the period of hostilities and until the passing of the Ministry of Transport Act, 1919.

For a number of years prior to 1914, consideration had been given to the question of railway facilities in the event of a war and a committee of general managers of the principal railways had deliberated on the various problems which were expected to arise. In particular, it had arranged for the preparation of a scheme for the expeditious mobilisation of troops and the transport of war material.

Control of British railways was vested in the Railway Executive Committee, the railway companies receiving the letter:

WAR OFFICE, LONDON, S.W.

79/3769 (Q.M.G.2)

Midnight, 4th–5th August, 1914.

Sir,

I am commanded by the Army Council to inform you that His Majesty the King has signed an Order in Council under the Provisions of the Regulations of the Forces Act of 1871, and that your Railway, including any Railway worked by you, is taken over by the Government under that Act.

You will carry on as usual, subject to the instructions of the Executive Committee, of which the President of the Board of Trade is Chairman. This Committee is located at 35 Parliament Street, S. W. Telegraphic address, ‘Studding, Parl, London’. Telephone number, ‘Central 3127 and 3128’.

Your attention is drawn to the Provisional Instructions to General Managers issued herewith.

I am to request you to acknowledge this communication.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient servant

The Secretary

(Signed) R. H. BRADE

….............................Railway

In practice, the President of the Board of Trade delegated his duties to the general manager of the London & South Western Railway, Herbert Walker, who for some time prior to the war had been chairman of the Railway Executive Committee (REC).

The War Office gave the REC 60 hours to assemble locomotives and rolling stock to convey the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to Southampton. This was achieved in 48 hours and embarkation began on 9 August and was completed by 31 August. During this period, from Southampton had been shipped 5,006 officers, 125,171 men, 38,805 horses, 344 guns, 1,575 other vehicles, 277 motor vehicles, 1,802 motor cycles and 6,406 tons of stores, using 711 trains. The busiest day was 22 August when seventy-three trains were dealt with, eight timed to arrive between 6.12 a.m. and 7.36 a.m., another eight between 12.12 p.m. and 1.36 p.m. and twenty-one more between 2.12 p.m. and 6.12 p.m. Within a quarter of an hour each train was emptied of troops, horses, guns and ammunition. This rapid arrival of the BEF in France surprised the Germans.

Between 1914 and 1918, 5,400,000 men were sent to fight in France and all travelled by train to south coast ports. Trains also carried needed supplies: arms, engineering materials, horses and their forage, food for the troops, mail, road stone and timber for duckboards and supporting the sides of trenches. Just one army division ate half a train’s worth of supplies every day. Initially, soldiers posted their laundry home and when returned it was often accompanied by cakes and other goodies.

It was only fair that the state should pay for this work carried out by the railway companies. The arrangement determined upon was that the net receipts as a whole of those companies of which possession had been taken were to be made up during the period of control to the 1913 level. During this period of control there was an abnormal increase in the remuneration of railway employees. Railway wages had not been fixed arbitrarily by the companies themselves, but were the result of arbitrations and agreements arrived at with the men through the machinery of the Conciliation Boards. By 1921 the railway wage bill had been increased by government direction from £47,000,000 in 1913 to £173,000,000, an advance of 268 per cent. In addition to increased wages, in September 1917 the government committed the railways to a permanent increase in expenditure. In response to agitation by the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen for a reduction in working hours, the President of the Board of Trade, in a communication with that society’s secretary, promised on behalf of the government, the War Cabinet and himself that any reasonable request after the cessation of hostilities for a shorter working day would receive the immediate and sympathetic consideration of the government. On 1 February 1919 the government conceded an 8-hour day to all railwaymen.

Until 1919 receipts had balanced expenditure, but from that year the companies made claims on the government to cover losses: for the year ending 31 March 1920, £41,349,530; to 31 March 1921, £40,445,411; and for the 2 months ending 31 May 1921, £18,638,424. Furthermore, the condition of the railways was deplorable: rolling stock was worn; maintenance and repairs were in arrears; development was at a standstill; traffic was disorganised; warehouses and sidings were congested; and the rates question was in confusion. Nobody was to blame for such a state of affairs, it was part of the price of war.

In September 1920 the Minister of Transport appointed the Colwyn Committee to grapple with the claims of the railway against the state for arrears of maintenance and it found that the sum would probably amount to at least £150 million. The committee could not admit that the companies were entitled to anything like such a sum and the Ministry of Transport was eventually able to reach a settlement whereby the railway companies accepted £60 million in full discharge of their claims.

2

RAILWAY GROUPING

Thus 7 years of government control had reduced the railway companies from being relatively prosperous commercial undertakings to a precarious financial position, for although Parliament had established the principle that increases in wage costs should be met by increased charges by the passing of the Railway and Canal Traffic Act, 1913, no steps had been taken by the government until January 1920 to increase rates and charges with a view to enabling the undertakings to be worked at a profit. Government representatives had declined to respond to the recommendation of the Railway Executive Committee that railway charges, in common with those in every other industry, should be advanced concurrently with increased costs of operation. The government gave an assurance that, in order to enable the companies to revert more gradually to pre-war conditions, the period of control with a guarantee of net receipts would be extended for 2 years after the end of the war.

On 26 February 1919 the Ways and Communications Bill (afterwards the Ministry of Transport Act) was introduced into Parliament. On 17 March, Sir E. Geddes in moving the second reading of the measure, explained that the government:

… has come to the conclusion that some measure of unified control of all systems of transportation is necessary – that there must be some body who can be asked what the transportation policy of a country is, and whose responsibility it is to have a policy. It is only the State, only the Government, that can centrally take that position.

It should be noted that the railway companies were not consulted on the framing of this bill, or notified of its intended provisions, before it was presented to the House of Commons. The bill provided for the appointment of a Minister of Transport to whom was to be transferred the powers and duties of the various government departments in relation to railways, tramways, canals, roads, harbours and docks. The control of the railways hitherto exercised by the Board of Trade was transferred to the Ministry of Transport. The period of state control of the railways, with a continuance of the guarantee of net receipts, was extended for 2 years from 15 August 1919, the date of the Act, ‘with a view to affording time for the consideration and formulation of the policy to be pursued as to the future position of the undertakings’.

The bill was read a second time on 18 March and a third time on 11 July, 245 voting for the third reading and none against. Royal Assent was given on 15 August 1919, the Act to be cited as the Ministry of Transport Act, 1919. The Railway Advisory Committee, which had succeeded the REC of the war period, was in association with the ministry.

In deciding what the government policy as to the future of the railways was to be, the Minister of Transport was faced with three alternatives:

1 To hand back the railways to their owners, weighed down with all the burdens which had accrued during the years of war and the extended period of control.

2 To unify the railway completely or partially under private ownership, with adjustments calculated to restore their dividend-earning power.

3 To nationalise the railways.

In June 1920 the government issued a White Paper (Command 787) containing an outline of its proposals and indicating that the government had chosen to adopt the second alternative. The suggestions put forward were exhaustively considered by all interests affected, and months of negotiations and discussions took place between the parties concerned – the government, representatives of the railway companies, railways users and railway employees. The result of these discussions was that on a number of points common ground was reached, but at the time of the introduction of the Railways Bill, 11 May 1921, there were still a number of important questions in regard to which there was a diversity of view.

In 1921 the initial thinking was in favour of having four English railways: the Great Western Railway annexing those in Wales; a Southern group; a combined North Western and Midland serving the west coast; and another group serving the east coast. Scotland would have two lines: the East Scottish made up of the North British and Great North of Scotland companies; and the West Scottish, composed of the Caledonian and the Glasgow & South Western.

Negotiations continued following the introduction of the measure and in its main details the Railways Act, 1921, found its place on the Statute Book agreed to and generally approved by those interests concerned in its successful operation.

The Act contained five main sets of provisions:

1 For the grouping of railways.

2 For disposing the claims of the railway companies against the state arising out of the wartime agreements.

3 Governing the future charging powers of the railway companies.

4 Machinery for dealing with questions relating to rates of pay and conditions of service of employees.

5 Regulation of railways.

During 1922 the Great Western acquired the Welsh companies by amalgamation, followed by the Didcot, Newbury & Southampton in the summer of 1923 and the Midland & South Western Junction on 28 September 1923. As the Great Western was easily the largest company in the western group, feeling ran high in Wales and, as a concession to local sentiment, the six local railways were eventually classified ‘constituent’ rather than ‘subsidiary’.

Grouping involved the disappearance of old and familiar names, as famous undertakings, some almost a century old, lost their identity in enlarged concerns. A total of 120 independent railways were merged into four large companies: the Great Western Railway (GWR); London, Midland and Scottish (LMS); London and North Eastern Railways (LNER); and Southern Railways (SR). In general, the larger railway companies were amalgamated while the smaller companies were absorbed (see Appendix 1). Alone of the great companies, the GWR retained the name borne since its incorporation in 1835. This was secured by a special provision in the Act which constituted the Great Western the amalgamated company for the western group.

The three major joint lines – the Cheshire Lines Committee, the Midland & Great Northern, and the Somerset & Dorset – continued as separate undertakings.

The amalgamation of railways was generally recognised as right in principle, in accordance with the history of railways which had been one of amalgamation. In total approximately 1,000 railways had been promoted in Great Britain, but by the process of amalgamation and absorption these had been reduced to about 200 at the time of the passing of the Railways Act.

In December 1923 the route mileage was 20,294 miles. Capital expenditure stood at £1,181,200,000. In round figures, total traffic receipts for 1923 were £205,900,000; of this £94,100,000 was contributed by coaching. Expenditure for the year was £166,100,000. Other items on the 1923 return were those given in Appendix 3, plus:

Private owners’ wagons

628,344

Motor buses

187

Horse buses

72

Parcels and goods motor vehicles

2,099

Horse wagons and carts

32,641

Passenger journeys:

First class

21,463,000

Second class

4,046,000

Third class

897,961,000

Workmen’s

310,273,000

Total

1,233,743,000

Season tickets:

First class

133,000

Second class

74,000

Third class

687,000

Total

894,000

General merchandise (tons)

58,773,000

Coal, coke and patent fuel

222,239,000

Other minerals (tons)

61,983,000

Total (tons)

342,995,000

Livestock

17,266,000

Train miles:

Coaching

251,669,000

Freight

143,114,000

Shunting coaching

16,980,000

Shunting freight

109,561,000

Engine miles

52,328,000

Total

590,918,000

Although many branches of railway service were dangerous, one great advantage of railway work was its permanent character. The mechanics employed at the companies’ manufacturing and repair shops had to face the uncertainty of this class of work, but even there the activity was more regular than in similar outside industries, while for those in sections more immediately concerned with the movement of traffic, there was more regular work than in almost any other industry. Railway service was therefore very highly regarded in respect of permanency of employment and regularity of income, often a family taking service with a company from generation to generation. Railway work offered very worthwhile perks to some workers: free uniform meant that no expenditure was required for working clothes; the railway companies supported pension and accident funds, while some employees were provided with housing for a reasonable rent, and free or reduced fares were available to all.

Although it did not seriously impinge on the Big Four, it should be mentioned that, set up by an Act of Parliament, on 1 July 1933 the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) came into existence, taking over the Metropolitan Railway together with all the underground railways, trams and buses within the designated area of almost 2,000 square miles. Within this area all suburban railway services were coordinated by a Standing Joint Committee comprising four representatives of the LPTB and the four main line railway general managers. All passenger receipts from this area, minus operating costs, were to be shared between the LPTB and the Big Four. In 1948, as with the Big Four, the LPTB was nationalised by the Transport Act of 1947, and the system taken over by the London Transport Executive, a subsidiary of the British Transport Commission.

3

AN OUTLINE OF THE MAIN PRE-GROUPING COMPANIES

Alexandra (Newport & South Wales) Docks & Railway

Although it owned only 9 miles of track, it had running powers over 88 miles of other companies’ metals and owned about 100 miles of track at Alexandra Docks, its North Dock of 28¾ acres being the largest single sheet of water held up by lock gates in the world. The lock entrance itself was the largest sea lock in the world at 1,000ft long and 100ft wide. Approximately 6 million tons of coal were shipped annually in addition to about 1 million tons of general cargo. As its traffic was short distance, all of its thirty-eight locomotives were of the tank design. Its four passenger coaches were third class only. The company was paying 5 per cent when it was taken over by the GWR in 1922 and was the smallest of the constituent companies named in the 1921 Act.

Barry Railway

The company began with an Act of 1884 to construct a line from the Rhondda Valley and build new docks at Barry Island, 8½ miles from Cardiff. It owned 47 miles of track and leased, or worked, a further 20 miles. All except four of its engines were of the tank variety, seven being 0-8-2Ts. It owned seventy-four coaching vehicles and carried first-, second- and third-class passengers. Merchandise traffic was slightly heavier than that of coal, coke and patent fuel. Between 1894 and 1920 the company paid dividends of 9½ to 10 per cent. As the Barry Railway served only the margins of the coalfield, much of the traffic for Barry Docks was brought by other railways to transfer points at Trehafod, Peterston and Bridgend.

Caledonian Railway

As the northern partner of the west coast route, the Caledonian Railway (CR) linked Carlisle with Glasgow and Edinburgh, and was the line royalty usually chose when travelling between England and Balmoral. Although the CR’s route to Scotland was remarkable for its directness, at some places it suffered from steep gradients, Beattock Bank being 9¾ miles with an average gradient of 1 in 75, accomplishing a rise of 600ft. The Wemyss Bay line and pier provided the shortest route between Glasgow and places on the lower reaches of the Firth of Clyde, the six steamers being operated by the Caledonian Steam Packet Company. In conjunction with the North British Railway, it operated a steamer service on Loch Lomond. It owned 896 miles of track, 1,067 locomotives and 2,287 passenger coaches equipped with the Westinghouse brake. Its most famous locomotive was the 4-6-0 Cardean.

Cambrian Railways

The Cambrian Railways was formed from the amalgamation of several railways in Mid Wales, which explained the plural in its name. Its main line ran for 95¾ miles from Whitchurch to Aberystwyth, with an extension northwards to Pwllheli and another to the south reaching Talyllyn Junction, where it tapped lines serving South Wales. Despite its name, quite a considerable proportion of its mileage was in England and its headquarters and workshops were situated in Oswestry, Shropshire. The GWR’s chief engineer reported that ‘a large amount of maintenance work would be necessary in the course of the next few years in the renewal of bridges on the Cambrian section, there being upwards of 600 timber structures on that section’. The Cambrian owned two narrow-gauge lines, 241 miles of track, 97 locomotives and 221 coaches. It amalgamated with the GWR as early as 1 January 1922.

Cardiff Railway

The Cardiff Railway was essentially a dock undertaking. In 1897 parliamentary powers were obtained by the Bute Docks Company for the construction of five branch lines some 12 miles in extent, thus inaugurating the Cardiff Railway, while the dock lines located within an area of 1½ square miles comprised a system of 120 miles. Its principal traffic was coal. It owned thirty-six locomotives, all of the tank variety, and eight passenger coaches.

Furness Railway

The line was originally for mineral traffic to Barrow, but later extensions were made to Whitehaven, Carnforth, Lake Side (Windermere) and Coniston. It operated two steamers on Coniston Lake and six on Windermere. It owned 114 miles of track, 138 locomotives and 362 passenger train vehicles.

Glasgow & South Western Railway

The first railway in Scotland, that between Kilmarnock and Troon, which opened in 1811, formed part of the Glasgow & South Western Railway (GSWR). The main line ran from Glasgow to Carlisle via Dumfries, with a branch to Challoch Junction near Stranraer. It owned 448 miles of track, 529 locomotives, 3 steam rail motors and 1,182 coaches.

Great Central Railway

Initially the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway, this consisted mainly of cross-country main lines from Manchester to Sheffield and thence to Lincoln, Grimsby and Cleethorpes, with branches to Barnsley, Wakefield and other centres. When it sought a London extension (opened for coal traffic on 25 July 1898 and passengers on 15 March 1899), its name was changed to the Great Central Railway (GCR). It then ranked among the first half-dozen railway companies regarding the magnitude of its goods and mineral traffic, taking a high rank among the passenger-carrying, dock-owning and steamship-operating systems of the UK. Anticipating the construction of a Channel tunnel, its London extension was built to the continental loading gauge.

Grimsby, the world’s premier fishing port, owed its prosperity to the enterprise of the GCR. The dock at Immingham was opened principally for the distribution of coal from South Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. It owned 11 steamships, 628 miles of track, 1,361 locomotives, 1 petrol-electric rail car, 16 electric tram cars and 1,087 carriages.

Great Eastern Railway

The Great Eastern Railway (GER) was an amalgamation of many railways serving virtually all of East Anglia together with important suburban lines in north-east London. In July 1920 the company inaugurated an intensive suburban train service on the Walthamstow, Chingford and Palace Gates lines. Although steam operated, it achieved results similar to those attained by electric traction, but the fact that the company used Westinghouse brakes was an important factor. Initially its port for continental traffic was Harwich until Parkeston Quay opened in 1883. The GER owned 16 steamers, 1,107 miles of track, 1,341 locomotives, and 3,970 coaches.

Great Northern Railway

The Great Northern Railway (GNR) formed the southern section of the east coast route and ran from King’s Cross to Doncaster, together with network in the Grantham and Leeds areas. The ruling gradient on its main line was 1 in 200 and so was suitable for fast services. It owned 696 miles of track, 1,359 locomotives, 6 steam rail motors and 2,795 coaches.

Great North of Scotland Railway

Centred on Aberdeen, lines ran to Peterhead, Fraserburgh, Lossiemouth, Boat of Garten and Ballater. It owned 334 miles of track, 122 locomotives and 454 coaches, Westinghouse-braked, and 38 buses. It possessed two electric tramcars to work the tramway connecting its station at Cruden Bay with its hotel. The line, 0.66 miles in length, carried passengers to the front door, while goods, via a short spur, were taken to the tradesmen’s entrance. Hotel passengers were carried free, but others were charged.

Great Western Railway

Originally the GWR ran from London to Bristol, but it expanded to cover much of the south-west, South Wales and inside a triangle formed by London, Bristol and Shrewsbury. Many of its routes were indirect, leading to the taunt that ‘GWR’ stood for ‘Great Way Round’. The GWR was a pioneer among railways in utilising road motor vehicles as feeders to its lines, inaugurating the first service on 17 August 1903. It owned 2,658 miles of track, 3,148 locomotives, 65 steam rail motors, 20 electric motor cars, 40 electric trailer cars, 5,581 coaches, 66 buses and 10 steamers.

Highland Railway

The Highland Railway (HR) ran from Perth to Thurso and Wick, with a branch to the Kyle of Lochalsh. It owned 484 miles of track, 173 locomotives and 305 coaches.

Hull & Barnsley Railway

The Hull & Barnsley Railway (HBR) ran from Hull to Wath and Stairfoot Junction. It owned 78 miles of track, 181 locomotives and 59 coaches.

Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway

The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway (LYR) chiefly covered the area in its title. It owned 533 miles of track, 1,650 locomotives, 18 steam rail motors, 3,731 coaches, 119 electric motor cars, 122 electric trailers and 22 steamers.

London & North Western Railway

The London & North Western Railway (LNWR) formed the southern part of the west coast route and ran from Euston to Carlisle, with branches serving North and South Wales. The company was the largest steamship-owning railway company in Great Britain. Regular services were operated between Holyhead and Ireland, Fleetwood and Belfast, Liverpool and Drogheda, Goole and continental ports. The company owned twenty-three steamers and then gained twenty-two more when it was amalgamated with the LYR in 1922 as a prelude to the 1923 grouping. The LNWR owned 1,806 miles of track, 3,336 locomotives, 7 steam and 1 petrol rail car, 73 electric motor coaches, 112 trailer coaches, 6,231 coaches, 5 motor buses, 7 horse buses and 5 electric trams.

London & South Western Railway

With a main line from Waterloo to Plymouth and Padstow, the London & South Western Railway (LSWR) served much of the south coast between Portsmouth and Weymouth and ran branches to Bude and Ilfracombe. It took over the Waterloo & City tube railway on 1 January 1907. It operated fourteen steamships between Southampton, French ports and the Channel Islands, and three on the ferry route from Lymington to Yarmouth. Steamers on the Portsmouth to Isle of Wight route were owned jointly with the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway. The LSWR owned 873 miles of track, 931 locomotives, 4 steam rail motors, 185 electric motor cars, 132 electric trailer cars and 2,645 coaches.

London, Brighton & South Coast Railway

The London, Brighton & South Coast Railway (LBSCR) ran from London to Eastbourne and Portsmouth, serving much of the territory between. Many of the coastal resorts were in favour all year round and express trains used by commuters were maintained throughout the year. An important feature was the inclusion of Pullman cars on the principal trains, and also the use of tank engines hauling many expresses. Continental traffic using twelve steamers via Newhaven and Dieppe formed an important item of business and was worked jointly with the French State Railways. Electric traction on the high-tension, single-phase system using overhead wires was inaugurated on 1 December 1909. The LBSCR owned 431 miles of track, 615 locomotives, 2 steam rail cars, and 1,870 coaches. It favoured the Westinghouse brake.

Midland Railway

The Midland Railway (MR) extended from Carlisle to Bristol and Bath, its joint ownership of the Somerset & Dorset Railway taking it on to Bournemouth. It also owned 265 miles of railway in Northern Ireland. The MR operated four steamers between Heysham and Belfast, and seven between Tilbury and Gravesend. In England it owned 1,521 miles of track, 3,019 steam locomotives, 1 electric locomotive, 48 electric motor cars, 49 trailer cars, 20 electric trams on the Burton & Ashby Light Railway and 4,331 coaches.

North British Railway

This ran from Berwick to Edinburgh, forming the northern part of the east coast route. It also ran from Carlisle to Edinburgh and Glasgow, with lines to Bervie and Mallaig. It operated six steamers on the Firth of Clyde, one Granton–Burntisland and another North–South Queensferry. It owned 1,275 miles of track,1,107 locomotives and 2,424 coaches.

North Eastern Railway

The North Eastern Railway (NER) ran from Hull, Selby and Leeds to Berwick, serving much of the country in between. It carried a heavier tonnage of mineral and coal traffic than any other railway in the country, the greater proportion of it in the company’s own wagons, and was the largest dock-owning railway company in the UK. The NER formed the middle link in the east coast London–Edinburgh route. It had 30 miles of electrified line in the Newcastle and Tynemouth area. The company owned 1,714 miles of track, 2,013 locomotives, 2 petrol rail cars, 3,104 coaches, 70 electric motor coaches and 55 trailers.

North Staffordshire Railway

The North Staffordshire Railway (NSR) radiated from Stoke-on-Trent and was popularly referred to as the ‘Knotty’. As it was a purely local line, there was probably not another British railway of its size and importance that was so little known in London. It owned 206 miles of track, 192 locomotives, 3 steam rail motors and 341 coaches.

Rhymney Railway

Although it consisted of only 51 miles of route, the Rhymney Railway (RR) reached out from Cardiff through Caerphilly, to Merthyr, Dowlais and Rhymney, making contact with several other Welsh railways and also the GWR and LNWR. The RR owned 38 miles of track, 123 locomotives and 131 coaches. Its 0-6-2T boilers were well maintained and long lasting, a significant number not needing to be replaced post-grouping with the GWR tapered variety.

South Eastern & Chatham Railway

An Act was passed in 1899 for the working union of the South Eastern Railway and the London, Chatham & Dover Railway, keeping the capital accounts separate. The South Eastern & Chatham Railway (SECR) ran from London to Margate and Bexhill, covering much of Kent and East Sussex. It owned 625 miles of track, and operated 13 steamers, 724 locomotives, 8 steam rail motors and 2,758 coaches.

Taff Vale Railway

The Taff Vale Railway (TVR) was the largest, oldest and, for many years, the most prosperous of the constituents which joined the GWR in 1922. The TVR’s original main line was from Cardiff to Merthyr Tydfil. The TVR was famous for the Pwllyrhebog Incline, ½ mile of 1 in 13. Worked as a balanced incline, it varied from others as to avoid breakaways, a locomotive propelled its train up the incline, the rope passing below the train to connect with the engine. The TVR owned 112 miles of track, 271 locomotives and 408 passenger train vehicles.

4

THE GREAT WESTERN RAILWAY

The GWR was the only pre-grouping company to retain its name and, as it was largely the same company with a few Welsh additions, it proceeded as before and was not confused by having to settle the different practices of various companies. When it came to the selection of the twenty-five directors for the GWR, it was obvious that the easiest course was to retain the nineteen existing directors and add six from the other companies. This was done by allowing each of the Welsh constituent companies to nominate a director.

The GWR was unique due to the fact that it was by far the largest company in the new group, whereas the other three new railways comprised several companies of similar size. The GWR had a route mileage of 2,784 while the next two largest companies by mileage were the Cambrian and Taff Vale, with only 280 and 124 miles respectively.