Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Mercier's History of the Irish Civil War

- Sprache: Englisch

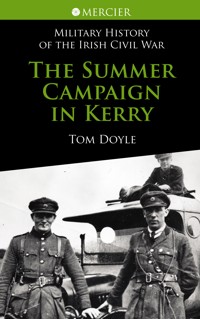

On Wednesday, 2 August 1922, Free State troops landed at Fenit pier in the first of a series of seaborne landings on the Cork and Kerry coast. This was a risky and ambitious strategy for the Free State government, whose aim was to surprise the staunchly anti-Treaty republicans in Kerry. By attacking them from an unexpected direction the government hoped to shorten the war, however, over the months of August and September, the republicans mounted a series of counterattacks against the Free State army. When Free State troops were all but surrounded in their barracks, the innovative invasion from the sea by Free State forces under Emmet Dalton caught the Republican forces almost completely by surprise. In this book Tom Doyle looks at the various successes and failures of both sides in Kerry during the Summer campaign of 1922 and how the superior forces of the Free State army and the lack of support from the people for the republicans allowed the Free State to build up a strong presence in a crucial part of the republicans' heartland.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 208

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MILITARY HISTORY OF THE IRISH CIVIL WAR

THE SUMMER CAMPAIGN IN KERRY

TOM DOYLE

SERIES EDITOR: GABRIEL DOHERTY

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland

www.mercierpress.ie

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Text: Tom Doyle, 2010

© Foreword: Gabriel Doherty, 2010

ISBN: 978 1 85635 676 3 ePub ISBN: 978 1 78117 070 0 Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 071 7

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1: From the Treaty Vote to the Kerry Landings

Chapter 2: The Quays of the Kingdom

Chapter 3: Gaining Ground, Holding Ground

Chapter 4: Republican Gains from Kenmare to Tarbert

Chapter 5: Killorglin: Attack and Turning Point in the Campaign

Chapter 6: Conclusion

Appendices

Endnotes

Select Bibliography

Images

Other Titles from Mercier Press

About the Author

About the Publisher

Kerry IRA Brigade structure 1919–1923

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book would not have been written without the assistance, help and encouragement of many people. I am particularly grateful to Michael Houlihan, Killorglin, whose knowledge of computers proved invaluable at every level in the compilation of this book. Special thanks are also due to Eoin Purcell for his advice and assistance.

I would like to thank many who work in various library services, among them Margaret O’Riordan, branch library, Killorglin; Michael Costello, Local Studies Department, Kerry County Library, Tralee; Mary Sorensen and Kieran Burke, Local Studies Department, Cork City Library; and all who enabled me to consult their vast archive of contemporary newspapers. I would also like to thank Bernadette Gardiner, College Library, NUI Maynooth, Co. Kildare, who enabled me to consult – via an interlibrary loan – Karl Murphy’s MA thesis (unpublished) on his grandfather General W.R.E. Murphy’s tenure as O/C Kerry, 1922–1923. Special thanks and sincere gratitude to Karl for allowing me to quote from his thesis on General Murphy’s involvement in the National Army, Kerry Campaign, August 1922 to January 1923. I would also like to thank Austin Reilly, Killorglin, Co. Kerry, Councillor Patrick O’Connor-Scarteen, Kenmare, Co. Kerry, Patrick J. Lynch, Tarbert, Co. Kerry, and John Sugrue, Cahirciveen, Co. Kerry, for allowing me to quote excerpts from The Ohermong Ambush by Michael Christopher (Dan) O’Shea. Thanks also to Hugh Beckett, Military Archives, Cathal Brugha Barracks, Dublin; Tom Broderick, Ordnance Survey Ireland, and the National Photographic Archive, Temple Bar, Dublin.

FOREWORD

The role played by Kerry-based IRA units during the War of Independence has at times been a matter of pointed disagreement among students of the Irish struggle for independence, with the balance of recent scholarship tending to the view that these units were more active than conveyed in some earlier accounts. What cannot be denied is that during the Civil War the county witnessed engagements that were as hard-fought as anywhere in the country, as well as some of the most notorious atrocities of the campaign. For a variety of reasons it is these latter actions (which for the most part occurred once the more fluid first stage of the hostilities settled down to the type of guerrilla warfare so familiar from the Anglo-Irish War) that have tended to dominate both public discussion and local popular memory of these terrible months.

Such a focus, however, tells only a part (if a major one) of the totality of the local experience. It certainly diverts attention from the arguably more significant months of July to September 1922, when the scales of war had not yet completely tipped in favour of the National Army, and when Kerry, in the minds of republicans near and far, was seen as much as a bridgehead as a redoubt. As Tom Doyle makes clear in this stimulating work, the balance of military advantage in the region was far from clear-cut during these weeks, with the victory of the forces of the Provisional Government in Limerick (examined in Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc’s volume in this series) being counter-balanced to some extent by the consequent concentration of (numerically strong) republican forces in their ‘heartland’ areas, their interior lines of communication and the stimulus provided by an awareness of the danger of imminent defeat. It is no exaggeration to say that during this period, culminating in the oft-neglected engagement at Killorglin, history lay in suspended animation. Certainly the leadership on both sides felt so. From the perspective of the Provisional Government this sense that a (or, rather, the) moment of crux had arrived was illustrated both by the deployment of ever-larger numbers of troops and by its recourse to emergency powers (legislation being too precise a word to describe parliamentary measures that were, by any standards, of dubious legal merit), while the sense of demoralisation evident amongst republican leaders at the end of September 1922 bore testimony to their realisation that victory had slipped definitively from their grasp.

Behind (or should that be before?) the intentions and actions of military leaders, however, were the fighting men of both sides and the local civilian population. Some of the most stimulating aspects of the book are those that examine how the ‘poor bloody infantry’, on whose shoulders rested defeat and victory, perceived their station, and (in welcome contrast to so many accounts of military campaigns) the sufferings of the non-combatants caught in the cross-fire (sometimes literally) receive due attention.

It is the balance between the book’s treatment of what approximated to ‘high’ politics and strategy, and its delineation of the experience of those, on both sides and none, who were daily exposed to the horrors of civil war, that is one of its principal merits. It is one that deepens and widens our knowledge of a seminal moment in the modern history of the island of Ireland. I certainly learned a lot from reading it; I believe you will too.

Gabriel DohertyDepartment of History University College Cork

Kerry railway network 1922–1923 During the Civil War, three distinct (private enterprise) railway companies operated in Kerry:

The Great Southern & Western Railway Company The Tralee to Dingle Railway Company The Listowel to Ballybunion Railway CompanyINTRODUCTION

In the three weeks between the bombardment of the Four Courts and the start of the shelling of republican strongpoints in Limerick city (28 June–19 July), anti-Treaty forces in both Dublin and Munster took little real action to pre-empt a government military offensive, with the exception of neutralising isolated outposts in Listowel and Skibbereen. In fact they allowed their enemies to determine the early pace and course of the war, despite their vastly superior numbers. At the cessation of hostilities in Dublin, the Provisional Government armed forces numbered little more than 5,000 troops based mostly in the capital. The republicans, on the other hand, had a pool of almost 13,000 volunteers (at least on paper) primarily located in the south and west of the country, who had access to an arsenal of 6,700 rifles.

Politically, Liam Lynch’s (IRA Chief-of-Staff) principal objective was to establish the ‘Republic’ – the ideological ‘Holy Grail’ – in Munster as a prelude to regaining the initiative nationally. But it is unclear what military policy, or series of strategic military objectives, anti-Treaty forces intended to follow to defeat the government’s army on the battlefield. Fundamentally, a republican victory would be a prelude to a resumption of the war against the British. Realistically, had Lynch’s forces carried all before them and marched on Dublin, it is probable that the British army would have intervened (alongside Free State forces) on behalf of the Provisional Government. This scenario was not a prospect that anyone in a position of authority in the Provisional Government wished to consider, except as a last resort.

Viewed from the Provisional Government’s GHQ in Dublin, Limerick city was the pivotal strategic military asset in anti-Treaty hands. It had to be neutralised to forestall further military action by the republicans. In early July republicans substantially outnumbered government troops (mainly Michael Brennan’s 1st Westerns) based in the city. During July, Brennan and Liam Lynch negotiated a series of truces/ceasefires – a huge tactical blunder on Lynch’s part – which bought time for Brennan and allowed Dublin to deploy additional troops, backed up by armoured cars and artillery, to the city. Once they were reinforced, government forces began shelling anti-Treaty fortified positions and three days later, on 21 July 1922, the remaining republicans surrendered. The impact of the defeat nationally was well summed up by Tom McEllistrim, one of the Kerry IRA column commanders engaged in defending the city, who noted: ‘Once we failed in Limerick, I knew the war was lost.’ Whether McEllistrim’s view was widely accepted among republicans in Munster or not, the fighting continued.

Kerry republicans, who were wholeheartedly anti-Treaty, saw the Civil War as a continuation of the War of Independence. In common with the IRA nationally, the Kerry brigades were not consulted by GHQ on the ceasefire or Truce terms. Similarly with the Treaty, they were presented with a fait accompli. To add insult to injury there was still considerable resentment of an overhaul GHQ had imposed on the Kerry brigades’ leadership during the summer of 1921. Superficially, Kerry republicans saw their refusal to deviate from the ‘Republic’ proclaimed in 1916 as proof of an ideological purity that had not been compromised by them, unlike the ideals that had been sullied by the plenipotentiaries in London. True, the Kerry republicans may have not deviated an inch, but the ground rules of the society within which the Civil War was taking place had altered beyond recognition from the War of Independence. The War of Independence never threatened Lloyd George’s ability to govern Britain, whereas for the Provisional Government a swift military victory was crucial for its political survival. Most Irish people were willing to endure the privations and hardships of 1919–1921 in the expectation of a reasonable political settlement from the British. The general election of 16 June 1922 saw ninety-two TDs returned to the Third Dáil who favoured parliamentary politics (fifty-eight who were pro-Treaty and thirty-four TDs who were ideologically neutral on the Treaty issue) as opposed to thirty-six anti-Treaty TDs, who abstained from participation in the new Dáil. On strictly military terms, GHQ had good intelligence on anti-Treaty forces and their leadership’s strengths and weaknesses. As well as this, alongside an overwhelming section of public opinion, the nascent government was also supported by the national press and the Catholic hierarchy.

The decision by the Provisional Government to launch a series of seaborne landings on the Cork and Kerry coast over a ten-day period (2–11 August) was an ambitious and risky strategy. Its success rested on two expectations: firstly, that republicans had prepared for a land-based offensive and had left their sea frontiers undefended, and secondly, that once Cork and Kerry IRA units based at the ‘Front’ learned of a Free State invasion, their automatic territorial attachment to their home counties would cause the Limerick/Tipperary front line to implode as the Cork and Kerry contingents returned home to defend their own heartlands. Evidently the military planners in GHQ (Collins, Mulcahy and Dalton) knew their enemy well. Collins’ choice to deploy both the Dublin Guards and the 1st Westerns – the most politically reliable and militarily competent forces at his disposal – to Kerry, is proof that he took the Kerry IRA’s opposition to his government very seriously.

Almost overnight, and without warning, 940 government troops gained a foothold at opposite ends of the county (Tarbert and Kenmare) and occupied the county town of Tralee, sustaining relatively few casualties. On 12 August, two days after the fall of Cork city, Collins was confident enough of his own position to personally visit Tralee with the aim of opening preparatory discussions with the republican leadership and negotiating an end to the war in Kerry. However, while in Tralee he learned of the death of his government colleague, Arthur Griffith. He cut short his visit, aborted the discussions agenda and returned to Dublin. Leaving Tralee, Collins probably felt he was witnessing the beginning of the end of republican resistance in Kerry. But to quote Winston Churchill on another conflict: ‘It was not the beginning of the end, rather, it was the end of the beginning.’

While the pro-Treaty force deployed to establish a secure foothold in Kerry had been sufficient to establish a beachhead, as it spread itself further and further across the county, its effect as a military force diminished. Perhaps half the initial landing of 940 troops was tied down to static positions by late August, in effect making pro-Treaty forces deployed in Kerry largely defensive in nature. By this time the republicans had virtually shut down Kerry’s rail network, forcing all military and civilian traffic onto the roads. Furthermore, virtually all the troops deployed in the county were from outside Kerry – with the exception of the Kenmare garrison – and the lack of local knowledge further stymied the force’s effectiveness. An additional 500–1,000 men would have tilted the balance in the Free State army’s favour, counteracting in some ways the natural advantages the Kerry IRA units possessed over their adversaries.

While the republicans could choose to ignore the political considerations that underpinned the conflict, the IRA in Kerry could not ignore the military realities that they had to deal with. Virtually overnight, the Provisional Government had been able to land 940 troops in Kerry and establish military control as a prelude to establishing ‘civil’ power and political authority over the county. Territory held by the republicans had been lost and both forces would now have to fight it out for control of the county. However, while the pro-Treaty forces had the initial success, within a week of the landings the IRA in Kerry had begun to recover their nerve. By early September – with prompting from Liam Deasy’s 1st Southern Division – Kerry IRA units were developing a co-ordinated strategy to attack all the military outposts in a town as a way of overwhelming the garrison. This strategy was to reach its zenith with the assault on Killorglin at the end of September 1922. It was the failure to achieve their objective in Killorglin on 27 September that marked a turning point in the IRA campaign in Kerry. From then on operations on this scale were never again attempted in the county. However, the passing of the Emergency Powers Act in the Dáil on the same day also acknowledged that after three months in the field, the efforts of the Provisional Government’s army on its own were not sufficient to defeat the republicans.

CHAPTER 1

FROM THE TREATY VOTE TO THE KERRY LANDINGS

On 7 January 1922, the Dáil endorsed the terms of the Treaty by sixty-four votes to fifty-seven, a pro-Treaty majority of seven. In a mature democracy that would have settled the issue – a majority vote in the Irish Assembly should have been accepted by the defeated faction. But many of the deputies returned in the May 1921 election came from the physical force tradition rather than a heritage imbued in constitutional and parliamentary procedures. As they viewed it, national independence had been won (and the Republic proclaimed in 1916 could still be achieved) by the IRA bullet rather than by a popular ballot.

During the vote on the Treaty, all members of the Dáil were entitled to outline their reasons for why they voted the way they did. The Kerry/West Limerick constituency had returned eight TDs (unopposed) on the Sinn Féin ticket in the 1921 general election, but only two of these TDs, Austin Stack and Fionán Lynch, representing opposite sides of the argument, elaborated and explained their positions. Austin Stack alluded to his Fenian heritage and the fact that his father had served time in an English jail for his republican ideals as reason enough to reject the Treaty. He also personalised his stance as one of loyalty to Éamon de Valera. Fionán Lynch approved the Treaty because it gave Ireland its own army, enabled the British army to withdraw from Ireland and gave the state control over its own financial and educational systems. The fact that Michael Collins was willing to accept the Treaty was sufficient reason to support it, Lynch argued. The remaining Kerry TDs did not contribute to the debate, but Thomas O’Donoghue and Paddy J. Cahill joined Austin Stack in the ‘No’ lobby, while Piaras Béaslaí and James Crowley voted in favour.

As a result of the pro-Treaty majority, de Valera resigned as president of the Dáil. On 10 January the Assembly reconvened to elect a new leader. De Valera ran as a candidate in an attempt to regain control of the Dáil agenda. However, Arthur Griffith won the vote, securing sixty votes to de Valera’s fifty-eight, whereupon de Valera and his supporters left the Dáil. On 14 January, the sixty pro-Treaty TDs and the four Unionist MPs returned by Dublin University (Trinity) formed a Provisional Government that would hold the reins of power until a ‘Free State’ (based on parliamentary elections) could be established.

Following Cathal Brugha’s resignation as Defence Minister on 10 January, Richard Mulcahy assumed responsibility for the IRA and its relationship with both the Dáil and the Provisional Government. The next day, 11 January, IRA leaders such as Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows, Oscar Traynor and Liam Lynch met and demanded that Mulcahy should hold a Volunteer Convention on 5 February, to ascertain the army’s position on the Treaty. This demand sent the Provisional Government a mixed message: on the one hand it gave Mulcahy de facto recognition as a government representative, but on the other proclaimed that the IRA’s loyalty to the Provisional Government (and the terms it accepted from the British) could not be taken for granted. Mulcahy managed to secure an extension of one month on the army convention. This 11 January meeting papered over the cracks in the IRA, preserving the myth of army unity, an essential prerequisite for the British withdrawal. From this point onwards, British military and police forces began to evacuate their barracks and other installations, and hand them over to local IRA units. They began evacuating the smaller and more remote areas of the country first, in the process giving anti-Treaty forces control of substantial parts of the country. Within a few weeks all the major towns in Kerry and their military installations were under republican control. For Collins this British military withdrawal was crucial, and – in the short term at least – more important than surrendering local control to his anti-Treaty adversaries. He was worried that anti-Treaty groups would attack crown forces as a way of reopening hostilities in the Anglo-Irish War.

Griffith argued that it would be to the government’s advantage to hold an election on the Treaty issue sooner rather than later, but Collins postponed a decision on the electoral front. In the spring of 1922 it was more important to him to preserve Sinn Féin and IRA ‘unity’ than obtain a popular mandate for the Treaty and the Provisional/Free State Government. The Provisional Government didn’t yet have an army to confront (nor did they want to challenge) their former comrades. So, by postponing a decision on the election, the new government could consolidate its position, and in so doing attempt to win over more people in the anti-Treaty camp to at least a ‘neutral’ position (i.e. opposed to the Treaty, but not willing to take up arms against the government). To do so was essential to the Provisional Government’s chances of survival, as many of the most experienced IRA members were initially staunchly anti-Treaty.

Even before the Dáil had voted on the issue in January, in Kerry all the brigade commanders had declared to the men under their jurisdiction that they would not support or argue for acceptance of the terms of the Treaty. To an extent their statement was a declaration of solidarity with the line taken by Austin Stack. In practical terms, Florence O’Donoghue, from Rathmore, and Deputy Leader of the IRA’s 1st Southern Division, estimated that during the War of Independence the Kerry IRA at full strength could draw from a pool of 8,750 Volunteers from their three brigade areas, broken down as follows:

Kerry No.1 Brigade4,000Kerry No.2 Brigade3,400Kerry No.3 Brigade1,3501Effectively about 1,000 of the Kerry IRA would take up arms against the Provisional Government and work to undermine and overthrow the regime it was imposing on Kerry and Ireland.

On 1 February 1922, the first unit of the Provisional Government’s army, resplendent in their new uniforms, marched past City Hall (where Collins took the salute) en route to Beggar’s Bush barracks, the National Army’s new headquarters. It was made up of forty-six men drawn mainly from the Dublin Brigade, under the command of thirty-two-year-old Captain Paddy O’Daly, the son of a Dublin Metropolitan Police officer from Clontarf, a veteran of the 1916 Rising and O/C of Collins’ ‘Squad’ during the War of Independence. This unit would grow and evolve into the Dublin Guards Regiment, which by the outbreak of hostilities in June/July would consist of two battalions (900–1,000 men) under Brigadier General O’Daly. Apart from the members of the ‘Squad’ (with its culture of assassination and personal loyalty to Collins), the new regiment also had a substantial number of pro-Treaty members of the Northern Division of the IRA (Donegal, Monaghan and Belfast) among its officers and other ranks, as well as raw recruits, predominantly Dubliners, who saw the army as a refuge from unemployment.

In Kerry, during the same month, a different army was making preparations for the conflict ahead, with a raid that was – superficially at least – the Civil War equivalent of the Gortlea raid of 1918. At 9 p.m. on Saturday 11 February, thirty armed men marched on Castleisland barracks, which was still occupied by twelve RIC constables. Locking the policemen in the guardroom, they took rifles, revolvers, arms, ammunition and grenades.2 It is almost certain that Tom McEllistrim’s column carried out the raid to make provision for what they believed was the inevitable confrontation when the Provisional Government tried to impose its writ on Kerry.

On 18 February, Commander Thomas Malone of the Mid Limerick Division publicly declared for the Republic, and repudiated GHQ’s claim to speak for the IRA. The move had serious implications for the government’s two provincial enclaves, Michael Brennan’s 1st Westerns in Clare and Seán McEoin’s forces in Athlone, both of which could potentially be isolated and overwhelmed by concerted attacks by anti-Treaty forces. A week later, Ernie O’Malley, Commander of the 2nd Southern Division (which included Malone’s Mid Limerick Brigade), raided Clonmel police depot. The republican units acquired 293 rifles, 273 revolvers, 3 Lewis (machine) guns and 324,000 rounds of ammunition, as well as 11 motor cars, making the 2nd Southern Division one of the best-equipped autonomous military groups in the country.3 It gave O’Malley huge leverage and he threw down the gauntlet to the Dublin Brigade and the 1st Westerns that GHQ had sent to Limerick to buttress up the small pro-government garrison, calling on them to leave the city. During a stand-off in late February and early March both sides brought in reinforcements, bringing both groups up to parity, with about 700 men on each side. On 10 March 1922, GHQ seized the initiative and Mulcahy summoned Liam Lynch and Oscar Traynor to Beggar’s Bush barracks (Dublin) to diffuse the situation. They persuaded O’Malley to back down. The resolution was a diplomatic ‘victory’ for Mulcahy, who learned a lot more from the experience than his anti-Treaty rivals.

Following what was in effect a regional coup attempt, Mulcahy took measures to give the Provisional Government a military presence in Munster, setting up garrisons at Skibbereen and Listowel in late February–early March. The Listowel unit consisted of about 250 men, mostly raw recruits, with NCOs and officers drawn from the War of Independence veterans who had declared themselves pro-Treaty at the start of the year. Under the command of Thomas J. Kennelly, who had led the North Kerry flying column during the War of Independence, the Kerry Brigade was billeted in Listowel workhouse. It was a well-equipped force, having received 200 rifles, 4 Lewis guns, large quantities of ammunition, new uniforms and a Crossley Tender (lorry) from GHQ on 3 March 1922.4 However, by late March 1922, anti-Treaty manpower and weaponry in the south and west of the country numbered 12,900 troops, who had an arsenal of 6,780 rifles.