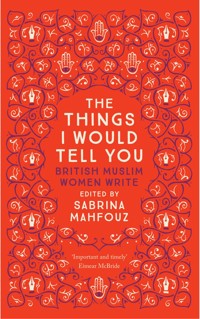

The Things I Would Tell You E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

From established literary heavyweights to emerging spoken word artists, the writers in this ground-breaking collection blow away the narrow image of the 'Muslim Woman'. Hear from users of Islamic Tinder, a disenchanted Maulana working as a TV chat show host and a plastic surgeon blackmailed by MI6. Follow the career of an actress with Middle-Eastern heritage whose dreams of playing a ghostbuster spiral into repeat castings as a jihadi bride. Among stories of honour killings and ill-fated love in besieged locations, we also find heart-warming connections and powerful challenges to the status quo.From Algiers to Brighton, these stories transcend time and place revealing just how varied the search for belonging can be.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 302

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Things I Would Tell You

The Things I Would Tell You

British Muslim Women Write

Edited by Sabrina Mahfouz

SAQI

Published 2017 by Saqi Books

Copyright © Sabrina Mahfouz 2017

Sabrina Mahfouz has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright for individual texts rests with the authors.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-0-86356-146-7eISBN 978-0-86356-151-1

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound by CPI Mackays, Chatham, ME5 8TD

Saqi Books

26 Westbourne Grove

London W2 5RH

www.saqibooks.com

Contents

Introduction

Fadia Faqir, Under the Cypress Tree

Amina Jama, Home, to a Man and other poems

Chimene SuleymanCutting Someone’s Heart Out with a Spoon

Us

Aliyah Hasinah Holder, Sentence and other poems

Kamila Shamsie, The Girl Next Door

Imtiaz Dharker, The Right Word and other poems

Triska Hamid, Islamic Tinder

Nafeesa Hamid, This Body Is Woman

Ahdaf Soueif, Mezzaterra

Seema Begum, Uomini Cadranno

Leila Aboulela, The Insider

Shazea Quraishi, Fallujah, Basrah and other poems

Shaista Aziz, Blood and Broken Bodies

Miss L, Stand By Me

Aisha Mirza, Staying Alive Through Brexit: Racism, Mental Health and Emotional Labour

Hibaq Osman, The Things I Would Tell You and other poems

Azra Tabassum, Brown Girl and other poems

Selma DabbaghTake Me There

Last Assignment to Jenin

Asma Elbadawi, Belongings and other poems

Samira Shackle, My Other Half

Sabrina Mahfouz, Battleface

Hanan al-Shaykh, An Eye That Sees

Biographies

Credits

Sabrina Mahfouz

Introduction

I felt upset and angered by the misrepresentations I encountered constantly and I felt grateful when a clear-eyed truth was spoken about us. And then again, who was ‘us’?

And so the question is asked by Ahdaf Soueif in Mezzaterra in relation to being a Muslim living in the West – who was ‘us’? It is a question that has prompted the creation of the book you hold in your hands. At the time of writing, this question is one that a person of Muslim heritage living in the West cannot possibly ignore, even if they hadn’t previously given it much thought. Our media is deluged by stories about Muslim extremists; Muslim moderates condemning the actions of Muslim extremists; non-Muslims bemoaning the fact that not enough moderate Muslims are condemning the actions of extremist Muslims; the possibilities of your Muslim-nextdoor becoming radicalised, perhaps even at their local primary school. This coverage has now been compounded by post-Brexit reports of a catastrophic rise in Islamophobic attacks across Britain, the majority of which have been targeted at women. The monitoring group on anti-Muslim attacks, Tell MAMA, states on its website that the rise in Islamophobic assaults reported to it in 2015 was already up 326 per cent, with the majority of perpetrators being young white males. There has also been a significant increase in hate crimes on public transport and social media, which many analysts view as unprecedented.

In some areas of the country, including London, women who wear Islamic clothing have reported being unable to leave the house for fear of abuse. ‘Islamic clothing’ could cover anything from a loose-fitting headscarf to a niqab (veil covering all of the face apart from the eyes) or an abaya (full-length, sleeveless outer garment). As one of the many thousands of women in this country with both a Muslim heritage and an aesthetic that can be easily assimilated into a European identity, who chooses to wear clothing that is not explicitly Islamic (though I do usually wear a head covering of sorts, as do many from other cultures), I am in the privileged position of not being a target for these attacks based on appearance.

In the face of such genuine cause for fear, it seems difficult to employ the arts in a truly effective and empowering way. However, one of the aims of this anthology is to dispel the narrow image of what a Muslim woman – particularly a British Muslim woman – looks and lives like. All of the contributors in this book identify as having both a British and a Muslim background or association, regardless of their birthplace, citizenship status or religiosity. The writers were born in or have parentage from countries including France, Iraq, Pakistan, India, Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Sudan, Somalia and Iran and yet they live, love, create and work in Britain.

Some of the writers featured in this anthology have made public proclamations about the importance of Islam in all aspects of their life; some are passionately secular; and others relate to Islam purely in terms of a cultural tradition that they have inherited. If we can offer an alternative to the current homogenous narrative of British Muslim identity – an alternative that is broadly representative rather than fabricated for political purposes – real change could be made in the lives of those who, as in Chimene Suleyman’s powerful story, Us, may be shouted at in the street, made to feel paralysed, threatened, unwelcome and, most heart-breakingly, scared for their loved ones in the very place they were born, live or work.

As gloomy as all this is, the words in the forthcoming pages are threaded together by a glow of strength, solidarity, possibility and hope. In Kamila Shamsie’s funny and sparkling short story The Girl Next Door, two young women with seemingly vastly different lives end up forming an unexpected and heart-warming connection. In Selma Dabbagh’s devastatingly touching and intense short stories Take Me There and Last Assignment to Jenin, romantic love (problematic though it may be) is shown to have a place even in the most unjustly besieged of locations. The poems of Imtiaz Dharker fizz with irony, cheekiness and a determination to challenge the status quo. Miss L’s Stand By Me is a hilarious but saddening account of trying to follow her dreams of becoming an actor as a British woman of Middle-Eastern heritage. It shows how far the creative industries – who often like to think of themselves as more progressive than others – have to go in terms of widening the representation of non-white people, especially minority women.

Important themes are tackled in this anthology, sometimes explicitly, as in the case of Shaista Aziz’s searing Blood and Broken Bodies, a damning account of honour killings in Pakistan. Aisha Mirza’s viscerally absorbing memoir of following the EU Referendum far from home, Staying Alive Through Brexit: Racism, Mental Health and Emotional Labour, succinctly explores many of the difficult issues the title suggests. They are also presented in more subtle ways, shown through the apposite choice of metaphor, geographical backdrop and character in Hibaq Osman’s collection of poems, one of which also provided the title for this anthology. They are there in each line of dialogue in Leila Aboulela’s play The Insider, set in Algeria, which follows some of the Arab characters featured briefly in Albert Camus’s The Outsider through the ages to the modern day.

In creating this anthology, it was vitally important to me that the reader was offered a range of narratives and writing styles – fiction, memoir, opinion, poetry, drama – that reflect the breadth and richness of these women writers’ work. The narratives take place across the globe: the authors take us from Karachi to Algiers, Palestine to New York, Yemen to Somalia and, eventually, we end up rooted in Britain.

Through these different mediums we meet characters such as Hanan al-Shaykh’s Tareq in An Eye That Sees, a Yemeni attendant at the V&A Museum in Kensington; the Iraqi children born in the aftermath of Britain’s bombing of Fallujah in Shazea Quraishi’s poetry; and the young women who are digitally searching for love in Triska Hamid’s exploration of Islamic Tinder. Fadia Faqir’s Doris, in the short story Under the Cypress Tree, is a delightful seaside character grappling with ageing, death, a constantly changing Britain and the alien Bedouin with special powers, who moved in next door. Throughout her poems, Azra Tabassum presents varied and intimate reflections of family members and the emotions their expectations elicit. We go to the Midlands with Aliyah Hasinah Holder’s poems, which include a bruising account of the effect of a private prison opening in the local area. These writers all offer an energising and eye-opening exploration of people and place, whatever medium they employ.

It was also important to include a mix of authors in terms of renown and experience. The anthology celebrates literary heavyweights such as Ahdaf Soueif, Kamila Shamsie, Leila Aboulela, Fadia Faqir and Hanan al-Shaykh. Between them, they have been short- or long-listed for four Orange Prizes, two Man Booker Prizes, and have won countless other awards and accolades for their work.

Alongside these renowned authors are emerging and new voices of British women of Muslim heritage. Writers such as Chimene Suleyman, Hibaq Osman, Aisha Mirza and Samira Shackle are published and respected writers who work internationally, yet they are at the early stages of their careers and bring exceptional energy and experimentation to the pages that follow. Aliyah Hasinah-Holder, Asma Elbadawi, Nafeesa Hamid and Amina Jama are tremendously talented writers published here for the first time. In spite of their young ages, their work is complex and compelling. Asma Elbadawi and Amina Jama, at only eighteen years of age, were winners of a nationwide search in 2015 by BBC 1xtra and The Roundhouse for the best new performance poets. They spent a year being mentored by The Roundhouse in London and their work has since featured on radio, TV and online. Though she is still at university, Nafeesa Hamid’s honesty and observations are dynamic and thought-provoking.

The contributors in this collection are an inspirational force. The fact that these women all have a British identity and a Muslim heritage is important, as the canon we are handed down and much of what is taught at school do not always provide those from diverse backgrounds with an opportunity to find writing that resonates with their own experiences. Nor does it lead them to writers who share similarities of background with them, allowing them to know that it is possible for them to write, to be published, to perform, to be read.

I work with girls and young women at schools, as well as with charitable organisations all over the world, and I have been stunned by the difference it has made to the writing of those who wear the hijab, for example, to watch a YouTube video of a young woman wearing a hijab and reciting her poetry on stage. Seema Begum, who was fourteen years old at the time, wrote her poem Uomini Cadranno in one such workshop. She demonstrates how negative stereotypes can be defeated through the written word. It never fails to surprise me how much representation can empower and how much non- or misrepresentation can disempower. We should never underestimate this, and we must do whatever we can to challenge the current dominant narrative. Through the vast variations of style and content that exist in this anthology, I hope you find that the following pieces all do exactly that.

London

Destroy the whole world

But leave London for me,

For it is here I feel at ease,

It is here that I am free.

Triska Hamid

Fadia Faqir

Under the Cypress Tree

She stepped out into the morning mist, a dark cloud extending and gathering like a swarm of flies. A veil, fixed with a band, covered her head and the collar of her padded jacket. The hem of her sharwal visible under her loose-fitting robe, her shoes flat. She shook the dust off her saddle bag, gathered her fardels and looked up. When Doris saw her weather-beaten skin, kohled-eyes and tattooed chin she held her breath and stepped back away from the window. A puff of cold air blew on Doris’s face. She blinked. All these layers of blackness, honestly. If she squatted next door she would bring the whole neighbourhood down to the level of whichever manhole she had crawled out of. Perhaps a bag lady with all of them colourful cloth bundles. How do you measure?

The war had started. They were at the Marigold when her father spilt the tea on his crotch. He ran to the gents, swearing. Full of sugar it was hot and sticky. Suddenly her mother’s mood changed. Grey clouds rushed and gathered across the sky. Later her father, stocky and assured, sat on a deckchair smoking his pipe. He was a collier on the jetty and was given a few days break in Brighton. He came home tired, his eyes watering, lips tight, shirt black and shoe covers caked with dark mud. They overheard the couple on the next table talk about barbed wire on the shore and fortifications. It was pelting down when they ran back to the guesthouse carrying their beach bags and rugs.

What with German bombers flying low above their heads Doris rarely stepped out of her flat. The most she did was water the lavender plant on the landing. She had to be extra careful now. While fiddling with the decorations something blocked the light and cast its shadow on the floor. It went cold, a chill that penetrated the very marrow of your bones. She had swirls and stars tattooed on her chin and she wore a few turquoise stones stringed together. Little cloth bags full of God-knows-what and feathers were knotted to her belt. The smell of dung and incense rose up.

The crone’s teeth were yellow. ‘Good morning! The weather not bad today.’

Doris pushed her glasses up and rubbed her arms. ‘Good morning.’

She put the broom down. ‘I Bedouin. Name Timam, your neighbour.’

Primitives rolled their eyes and bared their teeth on telly, somewhere in North Africa.

‘I go to market later, do you want anything?’ Her gold-clad tooth caught the sun.

Doris ran out of milk and bread. She hesitated. ‘No, thank you.’

Timam persevered. ‘What a lovely day! Cold, but sun. Is this Christmas tree?’

What did she bleeding know about Christmas, fresh from the desert? ‘Glad you like it.’

Timam sucked her teeth. ‘Honour meeting you.’

Doris slammed the door then locked and bolted it. Out of breath she sat on her favourite chair, right next to the gas fire and adjusted the crochet covers on the armrests. She checked her memorabilia: a black and white photo of her in a swimming suit and sunglasses next to a handsome man in uniform, another of a dog, a porcelain Russian ballerina, and Winston Churchill wearing a hat, a white suit, a poppy in his lapel, holding a walking stick. She also read the list of important phone numbers: 999 for emergencies, doctor’s surgery, the Local Council, DineWise elderly food delivery.

She fiddled with the knob of her temperamental radio until classical music floated out, a breeze of notes. Listening to the Waves of the Danube, she stretched her hands against the fire. It was spring. She was waltzing in a ballroom with a wooden floor and chandeliers with a man she barely knew. ‘A dance of too loose character for maidens to perform.’ Her narrowwaist taffeta dress tightened against her ribcage, restricting her breathing. A click of a lens. A young woman with blonde hair, red lips and dark eyelashes, legs shimmering in nylon tights, a cigarette in one hand and a glass of crème de cacao and gin in the other, leaning on the balcony of the King Alfred pub, watching the soldiers rushing in in herds. She lowered her glasses and ran her eyes over John’s waxed hair, large blue eyes, silly big ears and thin lips. With the back of her sleeve she wiped the glass frame and put the photo back on the side table. Spans. Spoons.

‘Insert two slices of bread in the toaster and watch them brown!’ Something that started with ‘s’ she ran out of often, a powder she knew she really liked. You spoon it then add it to tea. There was no milk in the fridge so she buttered the toast, put it with the mug of tea on a tray and took it to the sitting room. She switched the television on, had a sip then shouted, ‘Sugar!’

The bell rang. The dark crone from upstairs stuck her face to the door viewer. ‘Move away! I cannot see you!’

Timam stepped back and sucked her teeth.

Doris slid the safety chain open and unlocked the door. ‘What do you want?’

She flicked a green aromatic substance between her teeth. ‘I bought you milk from the old market. Here you are!’ She pushed it against her.

‘Are you chewing your snot? Honestly!’

‘No! How do you say? Cardamom!’

‘I see. . .’ Doris hesitated as she ran her fingers on the misty surface of the plastic bottle. She looked away then faced the beady kohled-eyes. ‘Thank you! That should do!’

Timam gathered her robe and skittered away.

Caddy jumped up then nibbled her foot. A black stocky dog, with a broad head, round eyes, small ears, saggy skin, that kept licking his snotty nostrils with his pink tongue. He waddled after her. The fire was lit and the kitchen was warm. Doris’s mother, still in her hat and coat, was drinking her Milo malt and cocoa and reading a magazine the lady she worked for in Chelsea had given her. Doris was eating a slice of cake and throwing the crumbs to Caddy. He chased them, collected them with his tongue then ate them snorting. ‘Don’t give him your food,’ her ma said and turned the page. ‘He’s so fat his tiny legs can barely carry him.’

‘But mother, he’s hungry.’

‘I just fed him the bones of yesterday’s broth.’ She inspected the magazine.

Caddy licked her bare feet and looked up, pleading. She threw down bits of cake.

‘You’ll not get your copper if you continue spoiling that dog.’

‘The way he looks at me, ma.’

Her dark hair was pulled back and neatly tucked under a round red hat, the buttons of her coat undone and her feet rested on the stool. She was reading loudly a recipe for pudding with cherries and custard. The rations wouldn’t stretch that far. Did they have any eggs?

Doris lost things quite often. She was looking for her glasses when she heard the knock on the door. ‘Go away!’

‘Please, Madam, open the door.’

The muffled voice of that dreaded woman!

‘I know you in there. Open the door! I have milk. It might sour.’

She stood by the window. A few black birds, perched on a chimney cowl, necked and then flew away. Doris opened the door.

Timam’s jacket was covered with snow flakes. ‘Here you are!’

‘I can’t find my glasses,’ Doris blurted.

Timam smoothed her long robe. ‘Don’t worry. I find for you.’

Doris, hesitated, stepped back and allowed her to cross the threshold.

The stink of sheep dung and the scent of something pleasant like eucalyptus filled the room.

Timam ran her hands on the sofa, coffee table, side table, television set and the carpet. ‘May I go to bathroom?’

‘You want to use it?’ Doris panicked.

‘See glasses.’

‘Yes, yes.’ She pressed her white muslin handkerchief over her nose.

‘Here they are! I wiped them real good.’

Doris put her glasses on, ran her fingers through her hair, stood up then buttoned her cardigan. ‘That would do. Thank you.’ She opened the front door.

Timam sucked her teeth, gathered her robe and went out. The war had started. Doris convulsed on the bed. The muscles of her arms and legs went into spasms and her back arched. Her temples were raw, saliva ran down her chin and her eyes spun as if she had just finished a big wheel ride at the fun fair. An incubator. White walls, sheets, a bed, a cabinet and a light bulb. The stench of disinfectant, vomit and urine filled her nostrils. Her forehead was covered with a thin layer of a foul-smelling paste. It was high voltage this time. When it hit her gums, it rattled her teeth. Was she caught in the blast? The reek of burnt flesh, leaking gas, powdered brickwork, and explosives filled the air. The sound of sirens, men shouting at each other, the crunch of broken glass underfoot and the crying of babies. She could hear the whistle of workers outside, smell concrete and fresh paint, and taste dust on her furry tongue. There was a presence in the room, a woman in a white uniform.

‘I can’t control me right hand. It keeps jumping about,’ Doris whispered.

‘Say that again.’

‘I can’t feel me head.’

‘Come again!’

‘Me hand has gone into spasms.’ Doris swallowed.

‘Don’t worry! It’ll calm down,’ the woman in white said.

‘Was I caught in the blitz?’

‘You could say that.’ She giggled.

‘Is he still on the front?’

‘Is your lover boy back?’

A blast then blood, thick and warm, ran down her thighs. Her father pelted her. She steadied herself, shifted her weight and faced the wall. Cracks. The window panes, filthy and held together with sticky tape, kept the light out. Spoons. Dry-eyed and slimy, she hissed like a lizard.

Timam kept knocking on the door. ‘It me your neighbour from upstairs.’

Doris opened the door and stood there, blocking the entrance. ‘What do you want?’ Her skin was dark and leathery, her nostrils flared and her chin tattooed with swirls and stars. The colour of ink.

‘I brought you something.’

‘Why? Is it Christmas already?’ She fumbled with her shirt buttons.

‘No. Not yet. But because you old lady.’ Timam stuck the gleaming bag in her hand.

‘You better come in.’ She stepped back.

Doris sat on the armed chair, opened the gift bag and pulled the scarf out. ‘It’s beautiful. All that embroidery!’ She ran her hand over it.

‘Belongs to great grandmother.’

‘Different shapes and patterns.’

‘Each mean something. Direct to a place. Like a life.’

Direct to a place. If only her English was better. ‘Thank you. It’s lovely.’ Doris pointed at the other armed chair.

Timam sat on the edge and adjusted her headband.

‘Do you want a cuppa?’ She rubbed her arthritic knee then stood up.

‘Yes, please.’

Doris came back with a cup of tea and some biscuits on a tray. She pulled a nest of tables and put the smallest in front of her.

Timam held the cup in both hands, had a sip then spat out. ‘So bitter.’ She added four spoons of sugar, stirred, drank and smiled, baring her yellow teeth.

The primitives ululated and hopped in the air. Doris settled in her chair, holding the gift bag. ‘How’re you finding living here then?’

‘Good. It so cold.’

‘That’s British weather for you.’ Kohl ran down the corners of her eyes like tears, her skin was rough and her shoes were dirty and worn out.

‘Although it cold the sun shinning.’

‘Oh! Yes! It is a typical autumn day.’ Doris bit on her dentures.

‘Perhaps we can go out. Say goodnight to everything.’

Goodnight. Honestly! ‘I never visited my mother’s grave.’ Doris didn’t know why she said that. She stood up, took the cup out of Timam’s hand and put it on the saucer. ‘Thank you for your gift. It’s time for me to have my lunch.’

Timam wrapped her padded jacket around her and went out.

It was a sunny day and Doris was getting ready to go out. Don’t worry about the bombs! Come to the Café de Paris! Doris was leaning on John’s arm outside.

‘Are you ready?’

‘Yes.’ Her heart thudded in her chest.

John held her hand and followed the usher to a table upstairs by the banister. The stars on his shoulder caught the light. Doris sat, smoothed down her dress, and wiped her forehead. How did the cigarette girls keep their hair so tightly curled? They must have paid a fortune to get it permed.

‘What would you like to drink?’ John’s eyes glistened as if they were full of tears.

‘Can I have cream de cacao please?’

‘Why don’t we start with champagne, darling? We don’t get to listen to Ken Johnson’s band every day.’

‘They call him “snakehips”.’

‘Do they?’

‘He danced so well in Oh Daddy!’

When John finished ordering the drinks and hors d’oeuvre he offered her a cigarette. She fidgeted in her chair. He watched her pull it out, fiddle with it then place it between her lips.

‘Let’s dance!’ he said like an afterthought.

The clanking of cutlery, animated conversation and piano music travelled to her ears. She wanted to show him Brighton. It was dark and the lights of the pier were reflected in the water, colourful and elongated. They stood bare-foot on the shore listening to the waves rustle along pebbles and sand then retreat back to the sea. His lips touched hers for the first time, a fleeting peck. He got closer, took off his cap, and kissed her so hard she felt his teeth grate against hers. The jolly sound of diners singing along to ‘It’s a Lovely Day Tomorrow’ was carried by the breeze to where they stood embracing, there on the shore by the barbed wire. Yards.

Doris showered, powdered herself with red rose perfume talc, pushed her dentures in and bit, put her glasses on, got dressed then opened the sitting room curtains, allowing the sunshine in. She was about to settle in her settee when the door bell rang. It was her neighbour in her full Bedouin regalia.

‘It me your neighbour Timam.’ She tilted her head backward.

‘Are you off to Her Majesty’s garden party at Buckingham Palace? All dressed up like that!’

‘No. I go to baker and butcher in the market. Do you buy anything?’

‘Did you say the baker?’ She pushed her glasses up.

‘Yes. Frightened man.’ Timam sat down on the sofa.

‘My mother loved the old-fashioned English custard tarts with thick wobbly filling. She loved the nutmeg flavour and the crisp pastry.’

‘I ask the baker. He will get for me if not in shop.’ She squatted in front of Doris and held her hands. The scent of acacia rose up. ‘You say you never go to your ma’s grave. We arrange visit.’

‘We arrange a visit to my mother’s grave?’ Doris freed her hands and pulled the collar of her shirt up.

‘Yes. We go together?’ Timam sucked her teeth.

‘Let me think about it. Here is some money.’ She took a five-pound note out of her purse.

‘No money!’

‘Take the money! I’ll write down that I’d given you five pounds so I won’t forget.’

‘No money. Later.’ She gathered her robe and went out.

Doris settled in her settee and began watching morning television. A doctor described the dangers of having sexual intercourse at an early age. ‘Young girls are not ready for it both physically and mentally.’ Her cheek was soft against her breasts, taut with milk. Chinese silk. Her eyes wandered. Just out of her, she was warm and clingy, clasping her fingers and toes around your arm like a hydra fresh out of a pond. Before her lips met her nipples, they put her up for adoption. Must not get too attached. An officer came round and found John’s face, which was blasted off, stuck over his shoulder. In electric shocks.

The painting of the oil jetty on the river Thames, hung above the fireplace, was grim. The silhouette of the cast-iron pillars of the jetty was dark against the sky and on the right a small boat was heading out to the shore. Her father used to work there. His eyes were bloodshot and his face covered with black dust when he held her tight and shook her. ‘You got your rocks off. Didn’t you?’ He then belted her. The buckle dug right into her side. Her skin bruised and flailed, she sat on the floor crying. ‘She’s not my daughter. I disown her. A harlot. That’s what she is.’ Her mother cried in the kitchen. Doris could hear her snivels. Caddy licked her feet.

Then she went away. Her ma sent her a letter. ‘I know how hard it is. Please hang on there, Doris. Caddy is missing you. He barks right into the night and stays outside waiting for you. I hear laughter in the bedroom and when I go to check you’re not there. What happened to us?’ Almost a year later she visited her and gave her the plate as a gift. She used to sneak in on her way back from work for a few minutes. Once she came when Doris was really bad. Her head was shaven and her forehead smeared with a blue paste. She kissed her. ‘Take care of yourself chuck!’ She never saw her again.

Timam knocked on the door, screaming, ‘The taxi here, mortal Doris.’

Mortal, honestly? Doris opened the door. Timam stood there, panting. Doris straightened her arthritic knee, held her walking stick and trudged out of the building for the first time in years. She stood on the pavement and breathed in the fresh air laden with the smell of grass and trees. She hadn’t seen all that brightness for a long time. Some you forget and others you remember. The warmth of the sun on her shoulders loosened them.

‘Taxi driver foreign friend. He very good and reasonable.’ Timam held the door open.

Doris sat in the back, put her walking stick against the front seat, put the plate, the custard tart and the letter in her lap and tidied up her hair. Timam gathered her layered attire and squeezed herself next to her.

When they settled in the taxi, the driver, a black man, looked in the front mirror. ‘Are you alright, girls?’

Girls! Girls! Honestly. Doris wound down the window and inhaled.

Shifting her weight onto the stick, Doris shuffled through the cemetery’s gate. Sycamore trees with ivy-wrapped trunks rose high, blocking the light of the sun. Blackberry bushes grew everywhere and the ground was blanketed with nettles.

‘We look, look for your mother’s grave until we find. What her name?’ Timam fingered the cloth bags, bottles and dry twigs tied to her belt.

‘Jane Robson was her married name. Her maiden name was Jane Asher.’

Timam scanned the sky.

‘Oh! Look the grave of Alexander Hurley!’ You could still read the writing although the headstone was cracked and chipped.

‘Who?’

‘The comedian who sang the ‘Lambeth Walk’. My mother used to listen to him on the wireless. Perhaps we will find her here.’

They followed the footpath among oak, beach and hazel trees, careful not to step on the flowering primroses.

‘Look crows want for food!’ Timam pointed at four black birds.

‘We’ll never find her in this bush. Look at it. Grass, weeds, trees everywhere. Like looking for a needle in. . . in. . .’

‘Don’t worry, we find it. We stay all day.’

They sat down on the ground exhausted. Doris’s hip and knee throbbed with a dull pain. It was getting dark and the wind picked up, bringing a chill with it.

‘I can hear starlings. They mimic noise, squeak, click.’ Timam looked up.

‘How do you know that?’ Doris buttoned up her coat.

‘Just know.’ She rubbed the leaf of a weed then sniffed her fingers.

Perhaps they should go back. She may be buried in another cemetery. How would she know? She cast the net of her mind far and wide and it came back empty. Blank except two fingers clasping a photograph of a cake.

Timam held Doris’s hand. It felt rough and warm against her skin. ‘We look again. Heart says we will find.’

Doris sighed and wiped the sweat off her forehead. That pain. This life. Measure if you dare.

They stood up and went through the overgrowth to the farthest corner of the walled cemetery, where the blackberry bushes were high and entangled. Timam parted the weeds and nettles with her bare hands and strode on. Doris stopped and pointed her walking stick at a grave you could hardly see. There it was! A humble headstone with ‘Jane Asher 1902–1958. May she rest in peace’ carved on it.

Timam kneeled down, spread her hands behind her ears, clicked her teeth, chanted a few foreign verses, blew on the grave then skittered away into the bush.

Was the crumbling headstone made of sand or lime? Could she restore the curve to the edges? Perhaps she could come one day and clear the area; get rid of the grass, bushes and weeds. Plant a geranium or two. Doris knelt down, put the custard tart on the plate, the letter on top and placed them carefully on the ground. ‘You don’t know how important the plate was to me. The two orange flowers drawn on each side, the grey foliage, and circa 1932 Tudor Ware were imprinted behind my eyeballs. Some things you cannot remember and others you cannot forget. Sixteen. Not my age. Electric shocks. I held on to the image of orange flowers until they turned into an open meadow, green, dew-covered, and dotted with forgetme-nots.’

Doris tried to conjure up her features, remember the colour of her eyes, the tilt of her head. All she could see was an image with the face cut out. Just her slim fingers holding the magazine and the red beret on her head. The nurses advised her to take a deep breath. She inhaled. Nothing. What about John’s? The name of the plant with delicate yellow flowers? Which word would describe that tall trunk with branches and leaves?

‘Where am I?’ Doris snivelled.

‘It time depart.’ Timam leapt out of the bushes and stuck the herbs she had gathered in different bags.

He must be resting under the cypress tree. Timam was cleaning Doris’s kitchen one morning when he arrived. She was expecting him. He whirled through the window past her. A thud. She rushed to the sitting room and found Doris on the floor, gasping for air. She lay there like a slain bird with her nightgown wrapped around her thigh. Grey-faced, clammy, she convulsed on the floor. Timam pulled the Fear Beaker out of her bundle, filled it with water, added some drops of orange blossom then blew on it. She helped Doris drink.

Doris saw the foreign words etched on the brass, the letters hooked to its edge, yet she drank then closed her eyes. A piercing pain in her chest, there where the ribs meet. Her windpipes tightened. Alone, in a dingy flat, besieged by foreigners. ‘Oh!’

Timam brewed a drink and gave it to Doris. The aroma of herbs was strong and sickly. She held the warm cup and had a sip. It was as bitter as barberry, but Doris had no option. She had to drink it.

Timam squatted on the floor and put Doris’s head on her thigh. ‘Relax! Breathe deep!’

Doris rasped, ‘My heart is beating. Chest tight. Cannot.’

‘Let go now. You say goodnight to your mum, to the streets.’ She stroked her hair, humming and muttering, until she went limp. Timam carried her to the sofa, took off her glasses, covered her with a blanket and adjusted her head on the pillow. A few minutes before she died she whispered something Timam could not understand. ‘Tell John I’ll meet him at the King Alfred. I’ll take Caddy with me. My ma was still missing. Keep the photos, plate and letter!’

‘Yes. Do your wishes.’ Timam sucked her teeth.

Her beady eyes were so close to Doris’ face she could see the honey-flecked irises. Two ink-coloured lines crossed her cracked lower lip. Never mind. Was her mother’s name Jane Asher? What about her? Was she Doris Robson? She nodded. The grass glistened with dew. Bluebells all the way from lavender to purple. Not to be confused with the hybrid breed. In the number of petals you plucked and counted. Droopy.

Timam held her. ‘Don’t tired yourself! Everything fine. Just breathe easy! We meet again!’

‘Meet again?’ Doris opened her eyes. A summer sky covered with hazy clouds.

‘Yes. Other end.’ She clicked her tongue.

Doris relaxed on the pillow and rubbed her fingers together for the very last time.

‘Must help.’ Timam pushed the band off her sweaty forehead and sat on the floor rocking and keening.