The Times on Cinema E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

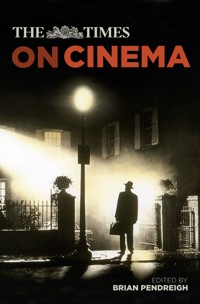

The Times on Cinema opens The Times' and the Sunday Times' vast archives of reviews and coverage of Hollywood's most treasured films. Featuring many of cinema's most revered critics, including Philip French, Dilys Powell, Tom Shone and Kate Muir, whose award-winning journalism has often determined the success or failure of a film, the book spans seven decades of film criticism. Editor and critic Brian Pendreigh also complies a selection of the most infamously scathing reviews ever to grace the pages of The Times, as well as a collection of legendary interviews with iconic actors, actresses, directors and producers, who lay bare the secrets to their successes. Featuring a range of rare film stills from The Times' collection, The Times on Cinema is the first book of its kind to make use of such an extensive archive, and is the perfect gift for all cinephiles.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 605

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Chris, Vin, Chico, Bernardo, Harry, Britt and (last, but not least) Lee … For me, it all began with you guys.

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Brian Pendreigh, 2018

The right of Brian Pendreigh to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8964 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

INTRODUCTION

By Brian Pendreigh, Editor

It’s a Wonderful Life: “Not a good film.” Unbylined review, April 5 1947

Dr. No: “Perhaps Mr Sean Connery will, with practice, get the ‘feel’ of the part a little more surely than he does here.”

Fight Club: “Starts out like a winner but fades fast.”

This is not a cricket book. Obviously.

But the idea began with cricket, and specifically Richard Whitehead’s book The Times on The Ashes. Richard then suggested I might edit a similar book on cinema. But the Ashes is a self-contained subject; it happens only every few years and Richard could pretty much just work his way through all the cuttings in The Times archives. Cinema happens all the time. It sprawls across the arts section, news pages, features and interviews, obituaries, even the sports pages.

19 May 1980. Carrie Fisher with a stormtrooper in London during the release of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. (Terry Richards)

Unlike Richard, I could not simply read everything ever written in The Times on cinema, going back in time beyond the birth of the talkies in 1927. I had to decide which films, people and subjects I wanted to look at, and then specifically search for those headings. And there are already plenty books on the history of cinema and another stack providing viewers with a comprehensive library of reviews, so this is neither of those, although it does include both cinema history and select film reviews.

So I dipped into the archives, and more than once discovered the cupboard was bare – there is no report on the first Oscars and only a single paragraph on the 1940 event, when Gone with the Wind won Best Picture, which is interesting in itself, I hope.

There are some obvious things in here: Citizen Kane and Harry Potter, Steven Spielberg and Alfred Hitchcock. But there are a lot of less obvious things too. I have included an obituary I wrote for Kay Mander. A little old lady in her mid-nineties when I met her for lunch in a hotel in a quiet corner of Kirkcudbrightshire, there was little in her appearance to suggest she had been a pioneer woman film director, let alone that she had once had a fling with Kirk Douglas.

And then there was John Chambers, who I visited in a care home in California years ago when writing a book on Planet of the Apes. He talked about his pioneering prosthetics work with disfigured servicemen and his landmark make-up on Star Trek and Planet of the Apes. What he did not talk about was the top secret work he had done for the CIA. It later provided the basis for the Oscar-winning film Argo, in which he was played by John Goodman.

This is not the history of cinema, but a dip into it, with my own linking material, context and/or commentary. It is not chronological. The selections are subjective and the book is to some extent personal – okay, Citizen Kane is there, but so is Grace of My Heart; The Birds is there, but so is Frogs, a similar sort of plot, but with frogs. “It is hard to worry very much even when we leave Ray Milland waiting alone in the last reel, presumably about to be gummed to death,” said our review. Personally, I loved it. Cinema is about great art, but it is also about guilty pleasures in darkened rooms.

Although some stories will be familiar, there is hopefully a lot here that will be unfamiliar for even the most dedicated Times readers and most devoted film fans – if not David Walliams’ take on James Bond and John Lasseter’s favourite animated films, then perhaps the story of Nell Shipman, who wrote, directed, produced and starred in her own films in the silent era; or perhaps which part of Britain doubled for the Adriatic in From Russia with Love; or the concerns that the addition of sound to movies might distract the audience’s attention from the images on the screen. “The special subtlety of acting which is peculiar to the film has been sacrificed, we feel, for a poor imitation of the stage,” wrote The Times reviewer in assessing The Jazz Singer.

Some films stand the test of time and some don’t. And, with all due respect to The Times critics over the years, some reviews stand the test of time, while there are some that the reviewer, with the benefit of hindsight and the invention of the DVD player, might have wanted to revise. Some readers might take issue with the assessment that It’s a Wonderful Life is “not a good film” as they sit down to watch it for the fourth Christmas in a row, but contemporary audiences did pretty much agree with the reviewer: the film flopped when it first came out. Until 1967 the reviews were unbylined, but the paper’s archivists have worked hard to establish retrospective credits for anonymous reviews and other articles. This particular review, like many others in this volume, was by Dudley Carew, a poet, novelist, cricket aficionado and close friend of Evelyn Waugh, who was the paper’s principal film critic from the 1940s to the early 1960s.

In many cases I have been able to juxtapose original reviews with later reassessments, and in the case of Brief Encounter I could not resist the temptation of juxtaposing the review of it with that for Fifty Shades of Grey. Perhaps it too will be reassessed at some future point – but that’s doubtful.

There are also quite a few lists, including a Top 100 from 2008. Second best film of all time? There Will Be Blood. Really? It just so happened to come out the previous year. The list is of its time, but no less interesting for that.

Some of the articles have been trimmed slightly for reasons of space. Some of the interviews were subject to slightly more substantial cuts, again because of space, and because this was always intended as a book the reader might dip into, hopefully, again and again.

CINEMA HISTORY

PAH-PAH-PAH-PAH-PAH-PAH, PAH-PAH-PAH

SOUNDTRACK TO A GENERATION OF FILM GOERS

By Bob Stanley, April 22 2010

There are some pieces of music that just exist, tunes you can’t imagine anyone sitting down and writing. The Pearl & Dean theme – or Asteroid to give it its proper name – breathes the same air as Happy Birthday to You and the chimes of Big Ben. It was written by the British arranger Pete Moore in 1968 and has accompanied cinema ads for Westler’s hot dogs, Butterkist popcorn, and hundreds of Indian restaurants ever since.

“When I wrote Asteroid,” Moore said in 2003, “many people in the profession accused me of writing music for the future, and ahead of its time. With the longevity of this music I thoroughly agree.”

You have to assume his tongue was firmly in his cheek, as it bears a rather strong resemblance to that late Sixties time capsule, MacArthur Park. As a teenager, decades before the internet, I remember trying to find out any information I could about the Pearl & Dean music. An unscrupulous record dealer told me it was a snippet of Hugo Montenegro’s version of MacArthur Park for which I paid him good pocket money, only to be disappointed. It turned out I was wasting my time. Asteroid was never released commercially until the Nineties – the only way you could hear it was by sitting in your local Odeon. When it finally surfaced on a compilation called Nice ‘n’ Easy, to my amazement, it turned out to be all of 20 seconds long. What you hear in the cinema is the alluring Asteroid in its entirely.

Moore’s claims to fame since include the theme for David Jacobs’s Radio 2 show, while his lounge classic Catwalk has cropped up on Alan Titchmarsh’s How to be a Gardener. He rerecorded Asteroid for a Pearl & Dean makeover in the Nineties, then in 2006 stretched it into a two-minute jazz odyssey. It took the Brighton ravers Goldbug to put it in the chart when they sampled it, along with the equally momentous Top of the Pops theme, on their ‘Whole Lotta Love’ hit in 1995. Moore’s CV includes sessions with Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby and Peggy Lee, but Asteroid’s bongos and angelic harmonies – the sound of popping corn and frying onions – will be his song for the ages.

Bob Stanley is a member of the pop group Saint Etienne.

CINEMA HISTORY

CINEMA PIONEER HONOURED AT GRAVESIDE

News report by Peter Waymark, May 6 1971

Family and former colleagues of William Friese-Greene, the cinema pioneer, honoured his memory on the fiftieth anniversary of his death at his grave in Highgate Cemetery, London, yesterday.

A grandson, Mr Anthony Friese-Greene, laid a wreath of roses and carnations at the stone monument designed by Sir Edward Lutyens and bearing the inscription “The Inventor of Kinematography”.

A second wreath, in the shape of the Maltese cross – an essential part of the cinema projector from the earliest days – was laid by officers of the Cinema Veterans Association.

The association, for people who have spent more than 40 years in the film industry, was formed shortly after Friese-Greene’s death on May 5, 1921. He was taken ill while addressing leading members of the industry in the Connaught Rooms, Holborn.

At the graveside were the widows of Friese-Greene’s sons, Graham and Claude, and another grandson, Mr Terry Friese-Greene. Mrs Claude Friese-Greene, aged 81, first met her father-in-law soon after the turn of the century: she remembered him as “a dear old thing, with a strong sense of humour and absolutely obsessed with his work”.

Humour he needed, for in spite of his taking out more than 70 patents connected with cinematography; his work was largely unrecognized during his lifetime and he died with only 1s 10d – then, ironically, the price of a cinema ticket – in his pocket.

The Magic Box

Unbylined review (Dudley Carew), September 13 1951

To commemorate the Festival (Festival of Britain), the British moving picture industry pooled its resources to make a film commemorating the life of the man who first made pictures move. An admirable idea, since it so happened that Friese-Greene, apart from being an inventor, was an eccentric after the English tradition of the creations of Dickens and H.G. Wells. Everything about his life was extravagant, varied, muddled, and unpredictable.

The cast reads like a programme for a Command performance, Mr Eric Ambler was appointed to write the script, Mr John Boulting to direct, and Mr Ronald Neame to produce. So far, so extremely promising, but the film proceeds at the outset to throw away most of the advantages which, in its inception, it possessed. It was to be expected that the story would be told in a series of flashbacks, moving leisurely and with care for detail over the years of a leisurely age, and so it is told and so it does move, but what was not foreseen was the diffidence with which Mr Robert Donat approaches the part of Friese-Greene himself.

It would have been legitimate to have presented him as an endearing mixture of Uncle Ponderevo and Mr Micawber, but Mr Donat plays him with a muted and diffident shyness which suggests that Friese-Greene was less a “character” and an inventor than some pathetic relation of Mr Chips. As a piece of acting it is sincere and conscientious, a virtue it shares with the film in general, but the man himself seldom breaks and erupts into life.

5 April 1951. Judy Garland aboard the liner Ile De France en route to Plymouth from New York, to appear at the London Palladium. (Fitz)

FLOPS

Editor’s note: The Wizard of Oz is now regarded not only as a Hollywood classic, but as a landmark in the history of cinema. Yet it actually lost money on its initial release. The Times reviewer was not impressed with the film overall and we are left to speculate what he thought specifically of Judy Garland or such songs as ‘Over the Rainbow’.

April 1951. Judy Garland with a bouquet of flowers from her daughter Liza, after appearing onstage in London for the first time in thirteen years. (Charles Trusler)

AN AMERICAN FAIRY TALE

The Wizard of Oz

Unbylined review, January 29 1940

Two of the new films this week are British and characteristic. The Band Wagon, with Mr Arthur Askey, which has made itself popular over the wireless, comes to the Leicester Square, and football finds its expression in The Arsenal Stadium Mystery, which is to be seen at the New Victoria and Astoria. The third film, The Wizard of Oz, at the Empire, is a lavish American fairy-story told, for the most part, in technicolour.

It is presumably to the credit of Hollywood that it can afford to deploy a whole army of dwarfs for the illustration of a single incident in a simple fairy story; this innumerable band of midgets reduces to insignificance the collection of the Gonzagas or, if it comes to that, of Philip IV of Spain. The rest of the spectacle is equally lavish; there are extraordinary vistas of artificial scenery, many amusing tricks and devices of the cinema, witches who fly in a very natural fashion, puffs of scarlet smoke, and a horse which changes its colour from brilliant purple to orange. In fact the ingenuous fairy story from which the film is adapted, the story of a little girl who wanders in a strange country in the company of stranger creatures to look for a wizard who will send her home, is quite overlaid by the fantastic elaboration of the setting. The only drawback to the spectacle is that there is scarcely anything in it to please the eye; although many of the conjuring tricks will certainly arouse one’s curiosity, the scenery and dresses are designed with no more taste than is commonly used in the decoration of a night-club. The film is, no doubt, a triumph of technical dexterity and especially of skill in colour photography, but what is the use of making a hollyhock out of cellophane, painting it an ugly colour, and then photographing it with complete accuracy?

CLASSIC FILM OF THE WEEK

The Wizard of Oz

Review by Kate Muir, September 12 2014

*****

While most of us have seen The Wizard of Oz on television, usually rolling in the background at Christmas, this 3D remastering of the original, on a giant IMAX screen to boot, brings a whole new sense of wonder to Dorothy’s yellow-brick road movie.

The initial scenes, shot in sepia, as the twister hits Aunt Em’s farmhouse in Kansas, take on a wild energy in 3D and seem all the more effective in these blasé days of CGI. The storm creates stomach-churning lurches and becomes frightening (at least to small children) until a granny flies by the window knitting in her rocking chair. The move to Technicolor, as Dorothy’s house lands squarely on the Wicked Witch of the East in Munchkinland, is suitably garish, although a little blurred in the deep background. Directed by Victor Fleming, the film remains in its original 4x3 Academy aspect ratio in IMAX.

You also forget how good a young actress Judy Garland was aged 16 as Dorothy Gale, avoiding artifice for sincerity, even when her eyes seem to be constantly pooling with emotion. Looking at the film again I was particularly impressed by Terry the black Cairn Terrier’s natural, unscripted performance as Toto.

And the soundtrack is as catchy as ever. Over the Rainbow won an Oscar for best song, but best picture that year went to Gone with the Wind. This Wizard of Oz restoration will entertain a modern child far more than the original and provide a perfect serving of nostalgia for adults. Like Dorothy says, we’re not in Kansas anymore. We’re in 3D IMAX.

PEOPLE

Karl Slover

Diminutive actor who was one of the last survivors of the 124 actors who appeared as the Munchkins in one of Hollywood’s greatest success stories, The Wizard of Oz

Obituary (Richard Whitehead), December 24 2011

Karl Slover was one of the last survivors of the 124 actors who appeared as the Munchkins in one of Hollywood’s greatest success stories, The Wizard of Oz. At 4ft 4in, Slover claimed to be the smallest of the Munchkins and was assigned four roles: lead trumpeter in the band, a soldier, a sleepy head and one of the characters who leads Judy Garland down the Yellow Brick Road. The roles brought him lasting fame but, initially at least, not wealth. “Toto [Garland’s dog] got a bigger fee than us,” he said. “He had a better agent.”

Slover was born Karl Kosiczky in 1918 in Prakendorf, which is now in Slovakia. As a child he was made to undergo a number of “treatments” for his dwarfism, including being buried in his back garden, immersed in hot oil until his skin blistered and attached to a stretching machine at a hospital. Eventually, frustrated that none of this worked, his father sold him to a travelling show when he was 9.

He toured Europe but moved to the United States in the late 1920s where he appeared in circuses and as part of a touring group known as the Singer Midgets. There were 30 members and they were recruited en masse to play the Munchkins when casting began for The Wizard of Oz.

The filming lasted two months and all the actors were subjected to a gruelling schedule. He was paid $50 a week, but when the film came out in 1939 it was an enormous success. [Editor’s note: The film actually lost money on initial release.] Initially, he had been assigned the role of second trumpeter but earned promotion when the selected actor was afflicted by stage fright. Slover’s various roles gave him little chance to rest. “I had four parts and each time I had to change clothes and do it so fast,” he said.

Slover also appeared in a 1938 western, The Terror of Tiny Town, billed as “the little guys with big guns”, and in the Laurel and Hardy classic Block-Heads (1938). He moved to Florida in 1942 where he joined a circus owned by Bert and Ada Slover. He became close to the couple and took their name.

Karl Slover, actor, was born on September 21, 1918. He died on November 15, 2011, aged 93.

JAMES BOND:PART ONE

WHAT’S THE BEST (AND WORST) BOND FILM EVER? EXPERTS RANK THE MOVIES

By Dominic Maxwell, October 15 2015

Which is the best James Bond film? With less than two weeks to go before Daniel Craig’s latest 007 adventure, Spectre, opens in British cinemas, we thought the time was right to put all its predecessors in a definitive order. To compile an official, definitive list of all the Bond films released to date, from best (1) to worst (24).

All right, so maybe this little vote of ours isn’t strictly official. It is, however, the most comprehensive poll of James Bond experts, to our knowledge, anyone has compiled. Steve Cole and Raymond Benson (novelists), Ben Macintyre and Andrew Lycett (Ian Fleming biographers), and David Walliams and Edgar Wright (film industry fans) are just some of the names involved.

We didn’t include the abominable spoof Casino Royale from 1967 – a film so bad it makes Die Another Day look like The Godfather – but left on the list the “unofficial” Thunderball remake, Never Say Never Again, the one film here not made by Bond’s (genuinely) official producer, Eon. Then we totted up the votes. There were only a few points between the top four films. The bottom choice, by contrast, was a runaway loser. Sorry, Pierce.

1. Casino Royale (2006, Daniel Craig)

Bond begins – belatedly, brutally, brilliantly – as Ian Fleming’s first novel finally gets the full Bond-film treatment, 44 years after Dr. No. It’s a modern action thriller that delivers on the thrills (the parkour chase! That bit at the airport!) but also has room for subtlety, symbolism, psychology and romance. Eva Green’s Vesper Lynd is Bond’s finest female foil – the label “Bond girl” has never felt so inadequate – the poker sequence is superbly sustained; Craig’s final, strategically withheld uttering of the words “the name’s Bond … James Bond” sends a shiver up the spine; the naked torture scene (pure Fleming) sends a shiver up a different part of a chap’s anatomy. Yeah, you wish that Venetian building at the end wasn’t quite so keen to collapse into the canal, but this is Bond as it should be: low on pathetic quips and unlikely gadgets, high on adrenaline and emotion, ambiguity and intrigue.

2. Goldfinger (1964, Sean Connery)

Casino Royale edged it out of our poll’s top slot – by millimetres – yet this remains the Bond film that other Bond films want to be when they grow up. Sean Connery, the suavest hard man in town, scrubs up a treat in dinner jacket, wetsuit and powder-blue towelling playsuit alike; tosses out the puns as if he actually enjoys them; electrifies as he battles to the death with Oddjob (the henchman’s henchman) in Ken Adam’s Fort Knox fantasia design. Then there’s Shirley Eaton covered in gold paint; Honor Blackman radiant in her leathers; the funky Aston Martin; the brassiest of theme songs; dynamite dialogue with the larger-than-life baddie. Bond (a laser beam fast approaching his crotch): “Do you expect me to talk?” Goldfinger: “No, Mr Bond, I expect you to die!”

March 2005. Daniel Craig poses with Eva Green (Bond’s leading lady Vesper) while filming Casino Royale in the Bahamas. (Paul Rogers)

Raymond Benson, author of six Bond novels: “Goldfinger is perhaps the most influential film of the 1960s in terms of pop culture. It spawned the big spy boom in other films, television and fashion. It set the gold standard for the action-adventure film.”

3. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969, George Lazenby)

Maligned at the time, now seen as one of the series’s most singular successes. Right, so Australian model George Lazenby is stiff; he’s also superb in the action scenes, tender when he has to be, and his first-time-actor’s unease fits in a story that puts Bond in protracted peril in Blofeld’s mountain-top clinic-cum-lair. The camerawork and the skiing are sensational – bolstered by John Barry’s best score – and Diana Rigg’s Tracy is fine enough to make our lothario vow to forsake all others. OHMSS still divides people; it got the most No 1 placings of any film in the poll, while others reject its early languor, or just Lazenby.

Steve Cole, author of Young Bond: Shoot to Kill: “There’s an energy and clout to the action scenes that Bond movies have seldom bettered.”

Matthew Parker, Bond author: “Diana Rigg steals it from a plank of wood.”

4. From Russia with Love (1963, Sean Connery)

The series hits its stride with a taut, glamorous, sometimes self-mocking Cold War thriller that introduces us to the scrupulously hierarchical Spectre organisation and its fiendish, faceless, cat-loving leader, Number 1 (later revealed as Ernst Stavro Blofeld). Features some of the best acting and best action of the series in the train face-off between Connery and Robert Shaw, who might yet have bested Bond if he’d only ordered the right kind of wine with his fish supper.

5. Dr. No (1962, Sean Connery)

The original and fifth best. An amazing amount of the series’s hallmarks are in place from the off – and Ursula Andress emerging from the sea remains one of the most celebrated moments in cinema – but the story itself looks a little stunted these days.

Simon Winder, author of The Man Who Saved Britain: “A marvel, of course, and the opening few seconds with the radio interference sounds making a segue to the theme tune could have a claim to be the fanfare marking the start of the 1960s, but it is also regrettably cheap-looking in some ways.”

6. The Spy Who Loved Me (1977, Roger Moore)

July 1977. Richard Kiel arriving for the premiere of The Spy Who Loved Me. (Dempsie)

November 2011. Actors at a photocall in London held to announce production starting for new James Bond film Skyfall. From left: Javier Bardem, Bérénice Marlohe, Sam Mendes, Dame Judi Dench, Daniel Craig, Naomie Harris, Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson. (David Bebber)

The best of the Moores, this is the one with the genuinely jaw-dropping opening title sequence (Bond skiing off a giant cliff before opening a Union Jack parachute); Carly Simon’s middle-of-the-road dream of a title tune; Jaws the giant henchman; the submarine-swallowing secret base that the designer Ken Adam secretly got his friend Stanley Kubrick to help him to light. Big fun.

7. Skyfall (2012, Daniel Craig)

If you can ignore some logical inconsistencies – and this is James Bond, I’d strongly suggest you try – this is one of the smartest, most stylish entries in the series. It’s certainly one of the best looking, thanks to Roger Deakins’s photography, and best acted, thanks to Craig, to vengeful peroxide-blonde nutjob Javier Bardem, and to Judi Dench, dying on the job in the only 007 film in which the baddie gets everything he wants. Also the only Bond film to earn $1 billion at the box office and, even adjusting for inflation, the biggest earner in the series (ahead of Thunderball and Goldfinger).

8. Thunderball (1965, Sean Connery)

The last gasps of Peak Connery – maximum insouciance, yet still looks as if he means business – this tropical long-weekend-cum-nuclear-ransom-race-against-time goes on to get waterlogged in the seemingly endless diving sequences. A 20-minute trim away from being one of the best.

9. You Only Live Twice (1967, Sean Connery)

In which Bond goes to Japan, Connery eyes the exit, and Donald Pleasence plays the most iconic incarnation of Blofeld, whose fully kitted, hollowed-out volcano remains the acme of supervillain secret bases even today. Top pub fact: Roald Dahl wrote the screenplay. And director Lewis Gilbert liked the plot so much that he repeated it, more or less, in his other two Bonds, The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker.

10. Live and Let Die (1973, Roger Moore)

Rog arrives, aged 45, but seizing the Seventies with Bond’s LED digital watch and preposterously professional coffee-making gear as M and Moneypenny visit him in his swish Chelsea flat. This is the one with voodoo, the speedboat chase, Jane Seymour, Paul McCartney’s theme, Sherriff JW Pepper and the exploding baddie “who always did have an inflated opinion of himself”.

Edgar Wright, film director (Shaun of the Dead, The World’s End): “Ridiculously entertaining. Bordering on silliness at times, but frequently weird and wild. Not the best, but perhaps my favourite.”

8 February 1973. Jane Seymour and Roger Moore in Live and Let Die.

11. GoldenEye (1995, Pierce Brosnan)

8 June 1994. Pierce Brosnan at a photocall after being announced as the new James Bond. (Michael Powell)

Brosnan arrives to rescue us from six Bondless years with the best of his four films, directed by Martin Campbell, who would go on to restart the series again with Casino Royale. Great opening bungee jump, a tank chase through Moscow, the arrival of Judi Dench’s M, Sean Bean acting “posh” as 006, and a sexy assassin who kills her victims between her thighs.

12. The Living Daylights (1987, Timothy Dalton)

The first of Dalton’s two post-Glasnost, post-AIDS outings is a spy thriller that starts in style in Europe but then, failing to learn the lessons of history, lingers too long in Afghanistan. Was to have been Pierce Brosnan’s first Bond film, but at the last minute the producers of his television series, Remington Steele, insisted he fulfil his contract and shoot a final season instead.

13. Diamonds Are Forever (1971, Sean Connery)

Lazenby resigns, Connery comes back for $1.25 million (which he donates to charity) and a production deal. The result: a scrappy, silly, stylish travelogue that takes a blank-looking Connery from London to Amsterdam to Las Vegas to a drab oil rig (looks as if all the money went on his salary) as the producers try to bring Bond back to his Goldfinger heyday. Pub fact: in early drafts the villain wasn’t Blofeld (camply played here by Charles Gray) but Goldfinger’s vengeful twin brother. A guilty pleasure.

14. Licence to Kill (1989, Timothy Dalton)

Bond goes rogue (back before he went rogue every bleeding film) to hunt the Central American drug lord responsible for his CIA buddy Felix Leiter losing a leg to a shark. The second and darker of Dalton’s two outings was not a big commercial success, but it hits its vengeful stride in its second half. A third Dalton was being planned before legal issues put the series “on hiatus” for six years.

Raymond Benson: “Totally underrated, in 1989 especially, it presented an accurate tone and feel of Fleming’s literary world, in particular the novel of Live and Let Die.”

15. The Man with the Golden Gun (1974, Roger Moore)

26 March 1974. Roger Moore and Britt Ekland. (Len Blandford)

A hurried effort, with some sorry sexism – Rog locks Britt Ekland in a cupboard while he has sex with Maud Adams – but it’s worth relishing Christopher Lee as the three-nippled assassin, Scaramanga, and an outstanding car-jump stunt, spoilt ever so slightly by the composer John Barry’s use of a swanee whistle to underline its gravity-defying bravado.

Roger Moore having fun in a photocall to promote the James Bond film Octopussy. (Steve Lewis)

16. For Your Eyes Only (1981, Roger Moore)

A reaction against the excesses of Moonraker, its return to ground-level espionage is hard to get excited by now. And 007 is starting to look less like an experienced older man, more “dad”: Rog was 53 when this was released, his love interest Carole Bouquet was 23. In an in-jokey pre-title sequence, Bond dumps an unnamed Blofeld – unavailable for use by the official series because of legal battles with the Thunderball producer Kevin McClory – down a chimney at Beckton gasworks in east London.

17. Octopussy (1983, Roger Moore)

Bond goes to India, Bond dresses up as a clown to defuse a nuclear bomb, Bond gets to bed a second sexy female criminal with “pussy” in her name. The American actor James Brolin tried out for the lead role before Moore was brought back to help to counter the threat from Connery’s return to bondage in Never Say Never Again that year.

18. Tomorrow Never Dies (1997, Pierce Brosnan)

The one with Jonathan Pryce as a malignant media mogul.

Simon Winder: “It is not really clear what goes so hopelessly wrong with Brosnan’s Bond. Brosnan himself has the air of a Moss Bros model worried about ripping his clothing – but it is far more than Brosnan’s fault. Scene after scene in this film is simply generic and everything smells of decaying versions of former glories.”

19. Moonraker (1979, Roger Moore)

Silly? Well, sure, but actually this set-piece-stuffed Moore extravaganza is nicely shot, globetrotting good fun – and that aerial pre-title sequence is amazing – until, uh-oh, it blasts off into orbit for laser battles.

Kevin Maher, Times film critic: “Nice to see Jaws again, but that space finale was horrendous in 1979, still sucks today.”

20. A View to a Kill (1985, Roger Moore)

17 August 1984. Roger Moore, Tanya Roberts and Grace Jones promoting A View to a Kill. (Steve Copely)

A Bond too far for our star. On the plus side: Duran Duran’s theme, Christopher Walken. On the minus side: the plot is a rubbishy rehash of Goldfinger; Bond snowboards to the tune of California Girls; Moore, now 57, is seen baking quiche. Quiche! Has its fans, mind.

Matt Gourley, co-host, James Bonding podcast: “This movie is snowboarding-Beach-Boys-Grace-Jones-Eiffel-Tower-base-jumping bats*** crazy and I love it.”

21. Quantum of Solace (2008, Daniel Craig)

The drabness of the villain’s plot – to defraud the people of Bolivia via inflated water rates, mouhahahaha! – is intentional, but the story’s satirical stabs at contemporary corporate larceny get lost amid shaky camerawork and rushed storytelling that lacks tension.

Simon Winder: “I was at one of the Casino Royale premieres and it ended with everyone cheering. The same event for Quantum of Solace ended in an embarrassed silence.”

29 October 2008. Daniel Craig and partner Satsuki Mitchell arrive at the Odeon in Leicester Square for the world premiere of the twenty-second Bond film Quantum of Solace. (Ally Carmichael)

22. The World Is Not Enough (1999, Pierce Brosnan)

22 November 1999. Pierce Brosnan and partner Keely Shaye Smith arriving in Leicester Square for the European premiere of The World is Not Enough. (Paul Rogers)

More not-quite-there Brosnanisms: one villain feels no pain (Robert Carlyle), the big villain is Bond’s girlfriend (Sophie Marceau), Desmond Llewelyn says goodbye as Q, yet the only thing that really lingers even vaguely in the memory is a speedboat chase. Oh, and Denise Richards in hot pants as the nuclear scientist Dr Christmas Jones. “I was wrong about you,” quips Bond as the pair finally get steamy together. “I thought Christmas only comes once a year.” Just call her Dr Goesliketheclappers Jones and be done with it.

23. Never Say Never Again (1983, Sean Connery)

Connery wigs up one last time for this deeply so-so remake of Thunderball, which for legal reasons was the only story available to producers in what was the only serious Bond film not to be made by Cubby Broccoli’s Eon productions. It doesn’t gel at all, even if Klaus Maria Brandauer and Barbara Carrera are nicely bonkers as the baddies.

24. Die Another Day (2002, Pierce Brosnan)

Our voters made this a clear favourite for the bottom slot. Its vulgar excesses prompted a rethink three years later, aka Casino Royale. Now that’s what I call a comeback.

Tom Sears, co-presenter, James Bond Radio: “Instead of the real Bond we get an invisible car; the worst dialogue in any film ever; the worst, most clichéd Bond girl ever in Halle Berry; the most ridiculous ‘stunt’ ever when Bond paraglides on a CGI tsunami; and the worst theme song of the entire series, by Madonna. I left the cinema a broken man.”

18 November 2002. Halle Berry arrives at the world premiere of Die Another Day at the Royal Albert Hall, London. (Alan Weller)

PEOPLE

Guy Hamilton

Urbane British director who shot four James Bond films and helped to introduce Roger Moore as 007

Obituary (Wendy Ide), April 22 2016

Tall, urbane, with a dry wit, distinguished naval career and a penchant for cocktails – and beautiful women – the director Guy Hamilton shared more than a few traits with the character with whom he was most closely associated, Commander James Bond.

As the director of Goldfinger (1964), Diamonds Are Forever (1971), Live and Let Die (1973) and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974), Hamilton helped to steward the series from its early popularity into the big, brash cultural phenomenon that it later became.

The son of a diplomat, he inherited some of his father’s expert skills of negotiation. Described as “curiously impersonal”, dressed often in a striped tie and blazer, and a great raconteur of war stories, he was the sort of man to whom film companies might entrust their millions.

He was also able to sneak the more risqué elements of the Bond films past the eagle eyes of the censors. He recalled showing them without sound effects – a trick used to downplay the violence and heavy petting and thus earn a U certificate. He meticulously fine-tuned the positioning of a cushion to conceal just enough of Shirley Eaton’s buttocks in order for the famous gold-painted nude scene from Goldfinger to pass uncut.

The key to his approach was, he said, walking “the line between absolute nonsense and seriousness”. He advocated intelligent baddies. “A Bond villain has to be [the] intellectual equal and a worthy opponent of Bond,” he said. He also acknowledged the importance of Bond girls – “A lot of 007’s appeal, let’s face it, stems from his doings with the ladies. So, find the ladies and we’ve won half the battle.” He helped to cast the little-known Swedish actress Maud Adams in The Man with the Golden Gun – “She was so elegant and beautiful that it seemed to me she was the perfect Bond girl”. He quipped, “One of the rules of the Bond pictures is that you’re not allowed to have a leading lady who can act.”

However, he was rather more interested in the gadgets, fast cars and aspirational kit. His Bond ethos was: “Don’t take a train when you can take a plane, and if you’re going to take a plane, take the newest one around. And if you give Bond a car, don’t show what’s been seen – show what’s not out yet.”

Guy Hamilton was born in 1922 in Paris where his father was a press attaché to the British Embassy. Instead of bowing to family pressure to follow his father into the diplomatic service, he decided he wanted to make films. “In those days it was like wanting to run a brothel and I got soundly spanked,” he said.

At 17, he applied to the Victorine studios in Nice, where he licked wage packets before getting onto the studio floor as a clapper boy. When the Second World War broke out he fled France with his mother on the same coal boat heading for North Africa as Somerset Maugham. He recalled the author’s butler brewing tea in a corned beef tin.

He worked briefly in England for a newsreel company before service in the navy. He was honoured with a DSC for his many missions, and recalled a hair-raising time with the French Resistance during a covert operation to ferry agents into occupied France. “First we stayed with a Breton family, but that got too hot for us,” he said. “When the Germans came snooping round they moved us out into this deserted shepherd’s hut in the middle of a forest. The Germans knew that we were around somewhere, but we evaded them, and were picked up four weeks later. I had a month’s holiday in Brittany.”

After the war, he returned to the film industry and, while still in his twenties, became assistant to the director Carol Reed. Hamilton was also assistant director to John Huston on the rough and ready shoot for The African Queen. One of his more onerous duties was to be responsible for the upkeep and transport of Katharine Hepburn’s personal toilet. “It was in her contract that she had her private lavatory, so there was a little pontoon with a little hut.”

He had his directorial debut in 1952 with The Ringer, a crisp version of an Edgar Wallace mystery. His first great commercial success was The Colditz Story (1954), a study of life in the prisoner-of-war camp which eschewed easy heroics and wry humour. He drew on his own experience: “It has a schoolboy enthusiasm to it. But we did behave a little like that.” By then a rising director, he seemed to tread water.

Goldfinger came as a welcome boost. It opened to Shirley Bassey’s dramatic theme. “Well, I don’t know whether it’s going to be a hit or not, Harry,” Hamilton told the producer of the Bond films, Harry Saltzman, “but I know dramatically, it works.” In 1969 he was then entrusted with The Battle of Britain, an expensive prestige project from Saltzman. Despite a cast in which almost every part was taken by a star, and aerial sequences featuring Hurricanes and Spitfires, it was a dull affair which did poorly at the box-office.

He was glad to return to the Bond films, helping to establish Roger Moore as the new 007 in Live and Let Die. He shot the carnival funeral scene so that fans “don’t even get to think about it”. He also persuaded Moore to cut his hair short in order to appear more establishment and encouraged the actor to slim down to 12 stone for stunts. “Nothing Bond does can be simple,” said Hamilton. He spent weeks flying over New Orleans in a helicopter surveying swamps and lagoons for locations.

At the start of the 1980s he helmed two Agatha Christie whodunnits produced by Lord Brabourne, The Mirror Crack’d and Evil Under the Sun. He later admitted that he was no fan of Christie and when first approached by Brabourne had told him he had got the wrong man.

Hamilton retired to his villa on Mallorca, where he had lived since the late Seventies. Built with his fee for Superman – from which he had later pulled out – it was a pink modernist complex on a mountainside with a swimming pool and cocktail bar. Here he could be found mixing Camparis with his wife perched on a barstool beside him.

Guy Hamilton, film director, was born on September 16, 1922. He died on April 20, 2016, aged 93.

CINEMA HISTORY

BUZZ LIGHTYEAR’S ONE LINER SHOOTS TO THE TOP AS BRITAIN’S FAVOURITE

Unbylined news report, November 4 2014

“To infinity … and beyond!”, the classic line from Buzz Lightyear, hero of Toy Story, has been named the best film quote of all time. The space ranger’s catchphrase came top of a poll conducted by the Radio Times to find the nation’s favourite movie one-liner.

Michael Caine’s famous phrase from The Italian Job, “You’re only supposed to blow the bloody doors off!”, took second place, followed by “Say hello to my little friend”, uttered by Al Pacino in the mob drama Scarface.

The top ten also features “He’s not the Messiah. He’s a very naughty boy!” from Monty Python’s Life of Brian, in fourth place, and “You’re gonna need a bigger boat” from the thriller Jaws, which came fifth.

“Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn!”, Clark Gable’s famous line from Gone with the Wind, took sixth place, ahead of the greatest Carry On line of all times, from Kenneth Williams as Julius Caesar in Carry On Cleo: “Infamy, infamy, they’ve all got it in for me!”

Next on the list are lines from Blade Runner (“All those moments will be lost in time... like tears in rain”) and Some Like It Hot (“Nobody’s perfect!”).

Richard E Grant’s classic line from Withnail and I rounds out the top ten: “We want the finest wines available to humanity. We want them here, and we want them now!”

But both Sean Connery’s “Bond. James Bond” from Dr. No, and Humphrey Bogart’s “Here’s looking at you, kid” from Casablanca missed out on the top ten.

CINEMA HISTORY

MARILYN MONROE FOUND DEAD

From Our Own Correspondent in New York, August 5 Published August 6 1962

Miss Marilyn Monroe, the film actress, was found dead in bed in her Los Angeles home, early today. The local coroner said the circumstances indicated a “possible suicide”. Miss Monroe, aged 36, had long been suffering from nervous trouble arising from both her professional and her personal life.

The police said Miss Monroe was found by two doctors, who had to break a window to get into her room. She was lying nude in bed with the sheet pulled up to her neck and a telephone in her hand. On the bedside table were bottles of medicines, including an empty bottle of Nembutal, a sleeping pill.

16 July 1956. Marilyn Monroe at a press conference in the Savoy Hotel. (Horace Tonge)

15 July 1956. Marilyn Monroe and her husband Arthur Miller receiving photographers in the grounds of Parkside House in Surrey. (Martin)

The doctors were called to the house after the housekeeper, noticing that Miss Monroe’s room lights remained on for several hours during the night, tried the door and found it locked.

The tragic circumstances of Miss Monroe’s life, from her early days as a waif sent from one set of foster-parents to another to her emergence as the “sex symbol” of America, are well known. What is less well known is that as a person she was warm-hearted, friendly and simple. Most people who met and spoke to her outside the glare of publicity (as your Correspondent did) found her a delightful person.

By a coincidence the latest issue of Life magazine carried an autobiographical article in which Miss Monroe tells how she felt about everything. She says: “Fame to me is only a temporary and a partial happiness – even for a waif, and I was brought up a waif. But fame is not really for a daily diet, that’s not what fulfils you. It warms you a bit, but the warming is temporary …”

“I was never used to being happy, so that wasn’t something I ever took for granted. I did sort of think, you know, marriage did that.” Her three marriages all ended in divorce.

FIRST FILMS

JOHNNY DEPP

A Nightmare on Elm Street

Review by David Robinson, August 30 1985

The touching quality in the juvenile audience which is today the economic life-blood of Hollywood is the will to be told the same stories and experience the same thrills over and over again. The most recurrent tale – deriving ultimately from The Phantom of the Opera – is about the creature who long ago was in some way abused and disfigured, and comes back to exact revenge by slaying the young offspring of the community that ill-used him (or her).

As writer-director of A Nightmare on Elm Street, Wes Craven succeeds in giving new life to the familiar theme. He explores an intriguing supernatural idea, supposing that the killer reaches his victims through their dreams: the spirited heroine alone works out the methods – mainly insomnia – to foil his schemes. An additional attraction of the film is that the youngsters are, for once, real characters, not plasticized dollies. Heather Langenkamp is the ingenious heroine, exasperated by the traditional obtuseness (in this genre of film) of grown-ups in general and cops in particular. Johnny Depp is her comically somnolent friend.

10 January 2008. Johnny Depp arrives in Leicester Square for the European premiere of Sweeney Todd. (David Bebber)

BLOCKBUSTERS

YO-HO TO HO-HUM

Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl

Disney’s new pirate movie could be a little more shipshape, says Sean Macaulay

Review published July 14 2003

Last week I joked about the trend of original films using colons trying to pass themselves off as sequels, but it is turning into an epidemic this summer. Disney’s latest “pre-branded” hit is Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl, a title which is cunningly designed to suggest the first of many adventures.

The film plundered an estimated $45 million over the weekend to open at No 1 at the US cinema box office. This may not be enough to warrant a sequel, but it is no small feat considering the curse of the pirate genre. Roman Polanski’s comedy Pirates was a spectacular misfire in 1985; the most expressive thing in it was Walter Matthau’s wooden leg. Renny Harlin’s Cutthroat Island made an even more spectacular nose-dive in 1995, costing $95 million and grossing $11 million. Pirates of the Caribbean re-works the old style without crushing it under ultra-modish editing or overly knowing humour.

Pirates of the Caribbean is drawing on a genre that had lapsed into high spoofery as early as the 1950s. Burt Lancaster’s The Crimson Pirate is the era’s classic swash-buckler, but it teeters over into action pantomime with its stripy tights and hearty, tooth-some acrobatics.

With nothing fresh left to spoof, Pirates of the Caribbean wisely gets on with minting its own fun. One of its pirates has a wooden eyeball. Another is a mute whose parrot does the talking for him. All of them have fabulously rotten teeth. It also draws on another antecedent, being the second film that Disney has based on one of its theme-park attractions. Last year saw The Care Bears Movie, based on a singing bear show at Disneyland.

There is some logic in basing a film on a theme-park ride. In the 1980s action adventure films tried to emulate the dips and climbs of the roller-coaster ride. Pirates of the Caribbean is duly overstuffed with gratuitous, faintly numbing action set pieces, which adds to a bloated running time of 2 hours 23 minutes.

The real culprit for this, though, is a mammoth first act. It takes 45 minutes for rogue pirate Johnny Depp to set off on his mission to rescue a cursed medallion and kidnapped beauty. Audiences all know this lift-off moment. It is when the plane takes off, the wagons roll, or, finally in this case, when the ship sets sail.

It is sacrosanct in Hollywood that any mission/journey/quest be underway by the 30-minute mark. Cramming more explosions and mass fights into the first act does not create better value. It just dilutes the impact of the fights and set pieces later on.

Nonetheless, the producer Jerry Bruckheimer has shown his dispiritingly consistent mastery in expediently combining the right elements to capture a mass audience. There is the action to lure teenage boys. There is sophisticated humour to appease the adults (Johnny Depp’s inspired Mockney accent and tipsy panache is half Keith Richards, half Dudley Moore). There’s a veneer of respectability to the scenery chewing with Oscar-winner Geoffrey Rush. And there’s the earnest young lovers sub-plot for the teenage date audience, shrewdly cast with new pin-ups Orlando (The Lord of the Rings) Bloom and Keira (Bend It Like Beckham) Knightley. A producer’s victory.

CINEMA HISTORY

Editor’s note: At the birth of the talkies, The Times reviewer goes all existential, while fearing that sound may distract viewers from what is actually happening on screen.

The Jazz Singer

Unbylined review (Albert Cookman), September 28 1928

The Jazz Singer, in which Mr Al Jolson may be both seen and heard, is only in part a “talking” film. Most of the story is told with the assistance of “captions”, but we hear half-a-dozen of the songs for which Mr Jolson is justly renowned on both sides of the Atlantic, and also one or two fragments of conversation. These appear as interruptions in the flow of visual images, and effectually encompass the ruin of the story, but they are interesting as the most considerable attempt to break the silence of the film drama which has yet been witnessed in this country.

It must be confessed, however, that we are less interested in the dramatic possibilities of the innovation than in its mechanical aspect. Synchronization has been almost perfectly achieved; words are precisely suited to the most trivial action; and our appreciation of a notable mechanical improvement is apt to cause us to overlook the tonelessness of the reproduction of Mr Jolson’s voice. In its present stage of development the sounds we hear are a faint parody of the human voice. They seem incapable of the fine shades on which a beautiful style of speaking depends. They would fail us, we feel, in any dramatic crisis which called for quiet intensities. These mechanical defects are no doubt temporary, but it is a more serious consideration that even when we become accustomed to the toneless quality of the sound reproduction we find that the sounds themselves divert our attention from what is passing on the screen. We become strangely aware of the interposition of two mediums between ourselves and the actor; we neither see nor hear him, but he is reproduced for us twice over. And after all the special subtlety of acting which is peculiar to the film has been sacrificed, we feel, for a poor imitation of the stage.

BLOCKBUSTERS

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

Review by James Christopher, December 22 2001

*****

Destined to become one of the seven marvels of the cinematic world, this spellbinding epic charts the story of how one humble Hobbit, Frodo Baggins, saves the world. Entrusted to destroy a magical ring of awesome power, the pint-sized Hobbits brave an army of mind-boggling horrors, too grisly for very young children. The film is a technical wonder. The most striking feature is the seamless join between the rugged New Zealand landscape and the fantastic digital universe that is Tolkien’s Middle-Earth. Jackson has created forests that seem to breathe evil. The greatest pleasure is the swamp life that stalks the heroes: rubbery orcs with bloodshot eyes, deathly Ringwraiths, and an awesome stone troll who will have you clutching your pillow in a damp sweat. The trip of the year.

10 December 2001. Dominic Monaghan (L), Elijah Wood (C) and Billy Boyd (R) arrive for the world premiere of the film Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring in London’s Leicester Square. (Richard Mills)

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers

Review by James Christopher, December 21 2002

****

The most eagerly awaited sequel of the year is a thrilling, bewildering sprawl of battles, pacts and snow-capped vistas. Half a dozen fractured storylines gallop along in tandem. Ian McKellen’s Gandalf fights with a demonic fiery demon in the depths of hell. Viggo Mortensen’s hunky Aragorn rides to the rescue of King Théoden (Bernard Hill), the last doddery hope for human kind. Orlando Bloom’s beautiful, deadly elf and John Rhys-Davies’s dwarf are tossed from one bloody fray into another. And a couple of new swashbucklers make their bow: David Wenham’s Faramir (brother of Sean Bean’s Boromir) is the spitting image of Jamie Oliver; Hill’s Théoden is handy with a sword when he wakes from a poisonous slumber. Meanwhile, Miranda Otto’s Eowyn drools over the strangely asexual Aragorn, and Christopher Lee’s Saruman continues to breed super-orcs.

And through it all plods Elijah Wood’s exhausted hobbit Frodo, the bearer of the Ring, crawling towards Mordor like a child to the gallows. The battle effects are magnificent, but the grim business of war makes the violence feel far more taxing than the Dungeons & Dragons thrills of The Fellowship. As ever, it’s the monsters that add the most enjoyable spice: Cockney-speaking orcs, sabre-toothed bears and, best of all, giant talking trees called Ents, which plod around forests like amiable wicker men. What we don’t get is close and consistent tension. Like most trilogies, The Lord of the Rings sags in the middle. Peter Jackson’s second episode is a vast schematic piece of action with large damp patches of, frankly, wooden acting. The camera seems forever perched on a horizon, gazing across distant plains at humourless armies of yodelling ogres.

Ultimately, the film is stolen by the wonderful Gollum, a slimy marvel who is voiced by and digitally modelled on the British actor Andy Serkis. With his ET eyes, lizardy skin and rotten toothpick teeth, this worshipper of the ring entices unexpected sympathy. It’s his mysterious love-hate relationship with Frodo that provides the darkest, and most human, chills.

I’M HOME, MY PRECIOUS

The Lord of the Rings:The Return of the King

Review by James Christopher, December 18 2003

*****

No one can claim that The Return of the King is great art, but as a Herculean endeavour it’s pure Boy’s Own Viagra. The plot hinges on Viggo Mortensen’s return to Gondor to reclaim his vacant throne but, frankly, who cares? The close-quarter horrors are very much the thrilling point. The Jurassic beasts in the last reel make stone trolls look very plain indeed. Shelob is a stomach-churning arachnophobic nightmare. Even the orcs, impossibly, look uglier. But it’s the parasitic relationship between the Ring, Frodo and Andy Serkis’s scene-stealing Gollum that gives the spectacle its unexpected gravity. The way Peter Jackson frames Gollum’s schizophrenia by putting him in front of a puddle is an inspired touch. The swashbucklers do their stuff with the usual wit and flair. The stunts are marvellous. Orlando Bloom has the best moment when he slaughters a galloping mammoth without breaking sweat. It brought spontaneous applause at the press screening. Ian McKellen milks Gandalf’s secrets like a man who has had one too many prunes. He’s always dashing offscreen left for no perceptible reason. And the hobbits are a keystone joy. At 201 minutes there are distinct longueurs. One can stomach only so much heroic dialogue. But these are light stings. The damn trilogy is a preposterous achievement. It has always been the scale of Jackson’s ambition that has impressed. If Frodo’s crawl towards the fires of Mordor plucks the heartstrings, it’s the bloodcurdling battle scenes and close-action photography of gristle and orc which leaves you weak at the knees.

CLASSIC CINEMA

MR NOËL COWARD’S NEW FILM

Brief Encounter

Unbylined review (Dudley Carew), November 22 1945

The title indicates fairly enough the scope and purpose of the film. A man and a woman, upper middle-class, early middle-aged, and married, meet by chance, fall in love, and, since they have no hope of happiness together and have their roots deep in lives that existed before the encounter took place, agree to part.

Mr Noël Coward has worked in a deliberately minor key, and while the notes are struck with an admirable clarity and precision, the composition is lacking in dramatic force and imaginative range. What emotion is distilled from a clever piece of observation and reporting is the result of the beautifully sincere and natural playing of Miss Celia Johnson as the woman who gets a piece of coal-dust in her eye while she is waiting on the platform for the train to take her home from her weekly shopping expedition, has it removed by a doctor and is disturbed to find that the trivial accident assumes a disproportionate importance. She and the doctor meet again, they fall desperately in love, and the whole unhappy, inconclusive affair is worked out against a background of railway buffets, cafes, cinemas, and the gossip and trivialities of provincial life.

There is guilt, humiliation, and a heroic integrity at the centre; the circumference is provided by Mr Stanley Holloway, as a ticket-collector, and Miss Joyce Carey, the refined goddess of the station refreshment room where the encounter has its trivial beginning and its tragic end – comic relief, perhaps, but not over-exaggerated or out of tune with the purpose of the whole. Mr Trevor Howard, as the doctor, matches Miss Johnson in casual charm of manner if he cannot equal her in emotional depth, and Miss Johnson has the difficulties of interpreting with her face close to the camera the audible progression of her secret thoughts – a clumsy device conspicuously out of place in a technically competent film which shows Mr Coward more as a serious psychologist than as a flippant commentator.

CLASSIC FILM OF THE WEEK

Brief Encounter

Review by Kate Muir, November 6 2015

*****

“You’re only middle-aged once,” says Trevor Howard as he leads Celia Johnson exquisitely astray in this very English affair of the heart. One of cinema’s classic love stories, Brief Encounter has been remastered for its 70th anniversary. White steam and inky blacks shroud this extramarital tryst, which begins with a mote of soot in the eye at the station and ends in an agony of longing.

Johnson plays the elegant, tweed-suited Laura. She is the epitome of upper middle-class suburban conventionality: a mother of two and, as she claims to be in her cut-glass accent (which takes some getting used to), “hippily merried”. But when she meets the helpful doctor Alec, the catchlights in her eyes go on full beam. The two lunch, drive in the country and play truant at the cinema for the afternoon matinee. For a time…

Written by Noël Coward, the subtle and deeply moving drama is seen from Laura’s point of view, often in impassioned voiceover as she sits quietly sewing while her dull, pleasant husband does The Times crossword.