17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

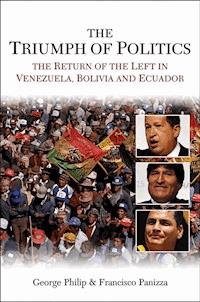

The Triumph of Politics offers a comparative and historical interpretation of Venezuela's Chavez, Bolivia's Morales and Ecuador's Correa - South America's most prominent '21st century socialists'. It argues that the claims of these 21st century socialists should be taken seriously even though not necessarily at face value. The authors show how the consensual market oriented policymaking that characterized almost all of South America in the 1990s has now given way to something quite different. Polarization and intense political conflict have returned to much of the region. Although the Left has not always been the beneficiary of this changed pattern, the '21st century' governments of Chavez, Morales and Correa have been agenda setters. The questions raised by their emergence, style of governance and policy orientations resonate across Latin America and beyond. It is likely that the kind of politics with which they have been associated will be influential in the region for quite some time to come.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 431

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT PAGE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

INTRODUCTION: THE TRIUMPH OF POLITICS IN VENEZUELA, BOLIVIA AND ECUADOR

Twenty-first century socialists in regional context

Other common factors: High politics and socio-economic issues

The logic of the book

1 THE MILITARY AND THE RISE OF THE LEFT

Crises and democratic near-breakdown: A comparative perspective

Changed patterns of military-political behaviour

Explaining military intervention without dictatorship

A Peruvian comparison

Crises and the rise of the left in Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia

Venezuela in 1989

Venezuela in February 1992

Venezuela in 1992 and 1993

Venezuela’s 2002 coup attempt

Ecuador in 1997

Ecuador in 2000: The Gutiérrez coup

Ecuador in 2005

Bolivia in the 1980s

Bolivia in 2003: The government collapses

Another government collapse: Bolivia in 2005

Conclusions

2 THE POLITICS OF MASS PROTESTS

The return of mass praetorianism?

Mass protests in comparative perspective

Indigenous movements and the politics of mass protests in Ecuador

Indigenous politics and political power in Bolivia

Inter-civil society conflicts in Bolivia

Conclusions

3 POPULISM AND THE RETURN OF THE POLITICAL

Twenty-first century populism in Latin America: Characterizing the politics of redistribution and recognition

Radical populism in twenty-first century Latin America

Bolivia: Re-founding the nation

Ecuador: A long tradition of populist politics

Venezuela: Radical populism and twenty-first century socialism

Conclusions

4 PERSONALISM, PLEBISCITES AND INSTITUTIONS

The problem: Presidential weakness in South America

The Venezuelan ‘solution’: From partidocracy to presidential rule

Plebiscitary politics in Ecuador and Bolivia

Plebiscites in regional context

The opposition responds: Recall votes under Chávez and Morales

Too much presidential power? Democracy and presidential re-election

By way of conclusion

5 THE POLITICS OF OIL AND GAS: TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SOCIALISM IN PRACTICE

Oil and gas issues: An overview

Venezuela: The decline and fall of PdVSA

Venezuela’s role in OPEC

Venezuelan oil prospects: An assessment

Bolivia, Brazil, and the 2006 gas nationalization

Concluding reflections

6 THE FAULT LINES OF LATIN AMERICAN INTEGRATION

The unravelling of the Miami Consensus and the transformations of MERCOSUR

Brazil and Venezuela: The politics of the new regional order

US–Latin American relations revisited

Conclusions

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

INDEX

Copyright © George Philip and Francisco Panizza 2011

The right of George Philip and Francisco Panizza to be identified as Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2011 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-4748-7

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-4749-4 (pb)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-5548-2 (epub)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-5549-9 (mobi)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Guy Burton and Ursula Durand for their help in reading the complete draft of the work and for their many helpful suggestions, both editorial and substantive. Thanks are also due to John Hughes for comments on chapter 1, to Gustavo Bonifaz, Carlos de la Torre and Sven Harten for their insights on chapters 2 and 3, toVesselin Dimitrov for his comments on chapter 4, to Dudley Ankerson for his comments on chapter 5 and to Dexter Boniface for his discussant role when an earlier version of chapter 1 was presented at the Ibero Americana in Mexico City.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AD Accion Democratica

ALBA Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América

COB Central Obrera Boliviana

CONAIE Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador

CONDEPA Conciencia de Patria

CODENPE Consejo de Desarrollo de las Nacionales y Pueblos del Ecuador

COPEI Comité de Organización Política Electoral Independiente

CPESC Confederaciones de las Personas Etnicas de Santa Cruz

CSO civil society organization

CSUTCB Confederación Sindical Única de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia

CTV Confederación de Trabajadores de Venezuela

FCO Foreign and Commonwealth Office

FEDECÁMERAS Federación Venezolana de Cameras y Asociaciones de Comercio y Producción

FETCTC Federación Especial de Trabajadores Campesinos del Trópico de Cochabamba

FTAA Free Trade Area of the Americas

IDB Inter-American Development Bank

IEA International Energy Agency

IMF International Monetary Fund

ISI Import Substituting Industrialization

MAS Movimiento al Socialismo

MERCOSUR Mercado Común del Sur

MIP Movimiento Indígena Pachakuti

MIR Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria

MNR Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario

MRTK Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Katari

MST Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra

NAFTA North American Free Trade Agreement

NGO Non-Governmental Organization

OAS Organization of American States

OPEC Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries

PdVSA Petróleos de Venezuela

PETROSUR Petróleos del Sur

PODEMOS Poder Democrático y Social

PSUV Partido Socialista Unificado de Venezuela

UNASUR Unión de Naciones Suramericanas

UCS Unidad Cívica Solidaridad

WHO World Health Organization

INTRODUCTION: THE TRIUMPH OF POLITICS IN VENEZUELA, BOLIVIA AND ECUADOR

During the 1990s, there was a broad consensus across most of Latin America on the desirability of free trade, market reform, representative democracy and ‘good governance’ – a concept that included the strengthening of autonomous institutions in areas such as law enforcement. This can be called the ‘Miami Consensus’ after the heads of government meeting in that city in 1994. It was compatible with but broader than the so-called Washington Consensus, which focused mostly on specifically economic issues (Williamson 1990).

This is not to say that the entire region adopted ‘Miami Consensus’ principles in practice, or even in aspiration. There are some cases where this clearly did not happen. For example, Cuba’s version of communism survived the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Fujimori’s Peru was much closer to being a personalist autocracy than a representative democracy. There were also many examples of ‘bad governance’ in almost every country and a significant degree of political turbulence in many.

The claim being made here is more about internationally accepted normative ideas. The decade from 1982–91 saw some dramatic events impact on the region, the vast majority of which worked to discredit ideas of economic nationalism, authoritarianism and left-wing political radicalism – all of which were at certain periods in the past very influential in Latin America. As well as the ending of the Cold War and the collapse of Soviet communism, there were also regionally significant events. These included the debt crisis that hit Latin America in 1982 and lasted in many countries for the rest of the decade, the military defeat of the Argentine junta in the South Atlantic in the same year, the experience of hyperinflation in several countries, and the US-sponsored Brady Plan which offered some debt forgiveness in return for economic reforms. In this new context, the majority of Latin American governments pushed ahead enthusiastically with both market and governance reform and were often rewarded with re-election. This trend was widely noted. For example, the Inter-American Development Bank’s (IDB) Annual Report for 1997 started with the claim that ‘Over the past ten years, the countries of Latin America have come into their own as democratic societies and market economies’ (Inter-American Development Bank 1997). In retrospect, this claim proved premature, but it seemed plausible to many people at the time.

Today, however, fundamental ideological debate has returned to much of the region. A key step in this transformation was the election of Hugo Chávez to the presidency of Venezuela in December 1998. Whatever his faults, Chávez has never lacked ambition or leadership skills and he soon made it clear that he saw himself as a challenger to almost the whole set of ‘Miami Consensus’ ideas. He is not the only such challenger, but he is one of the most determined and personally effective ones.

Chávez has now enjoyed more than a decade of power in Venezuela. His election was followed more recently by the first electoral victories of his political allies Evo Morales in Bolivia (in 2005) and Rafael Correa in Ecuador (in 2006). These three clearly represent a radical brand of left-wing politics – this book will adopt their self-identification as ‘twenty-first century socialists’ – that distinguishes them in significant ways from the rest of Latin America. There are however some ways in which all three – in breaking radically from the ‘Miami Consensus’ – have brought back some traditional Latin American ideas to do with political organization, political rhetoric and economic policy. At least some of the notions which seemed hopelessly discredited at the time of the Miami Consensus have been resuscitated by the three, alongside some genuinely new ideas and political tactics. This book departs from the argument that the political strategies, ideas and claims made by the three need to be taken seriously although not necessarily at face value. It claims that the combination of novelty and Old Left values that all three embody represents something important and distinctive in the politics of the region as a whole. Their willingness to use both electoral and extra-constitutional tactics against democratically elected governments and legislatures, their radical populist rhetoric, their use of plebiscites to strengthen the presidency, their economic nationalism and strong anti-US stance together form a distinctive political brew.

Twenty-first century socialists in regional context

Chávez, Morales and Correa are not complete outliers in every respect. Indeed, left-of-centre presidential candidates have achieved considerable electoral success in quite a number of Latin American countries during the past decade. However, we are dealing here with a particular kind of left. Where it has achieved electoral success elsewhere in the region, the left has often been far less personalist and far more institutionalist than Chávez, Morales and Correa have. This contrast is commonly drawn in the literature (Castañeda 2006; Panizza 2009; Reid 2007) and both sides generally recognize it, despite describing it in somewhat different ways. Indeed, there have been times when Chávez and Lula, the president of Brazil during 2002–10, have been seen as rivals for the intellectual leadership of South America. Even though it may be true that Lula – like Chávez, Morales and Correa – entered politics as an outsider and largely built up his own political party, there are more differences between them than similarities.

Of all the major countries in Latin America, Argentina is probably the least dissimilar in terms of governance to our three cases. Carlos Menem, president throughout the 1990s, pursued essentially a ‘Miami Consensus’ agenda – though his critics saw his presidency as somewhat autocratic (O’Donnell 1994). Argentina’s radical free market economic policies ended in severe crisis in 2001–3, for which they were largely blamed. Argentina then moved to the left as a reaction.

In the respect that Argentina moved to the left in reaction to the perception that market economics had failed, there is an evident similarity in political trajectory with Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador. Other points of similarity include the fact that, at the deepest point of its economic crisis, Argentina experienced intense street protests that temporarily destabilized the entire political system. Moreover, though winning elections after the worst of the economic crisis had passed, both Néstor and Cristina Kirchner (presidents 2003–7 and since 2007 respectively) sought to centralize power in the presidency and repeatedly used (and possibly exceeded) their constitutional powers to legislate by presidential decree. There has also been a degree of political friendship between Argentina under Néstor and Cristina Kirchner and Venezuela under Chávez.

However, in the end, the focus of this book is mainly on areas in which the differences between Argentina and our three cases outweigh their similarities. Most important is the fact that neither member of the Kirchner family successfully changed the bases of Argentina’s political system, either when seeking power or maintaining it. Instead, they have operated within Argentina’s admittedly rather flexible institutions. Néstor Kirchner was very much an insider, though by no means a national leader, when he first became president in 2003. Although the Kirchners have sought to acquire a political base of their own since 2003, they remain Peronists and their leadership of Peronism is far from undisputed. Some observers have commented on similarities between Chávez in particular and the original Peronist movement of the 1940s (there are differences as well), but this only serves to highlight some of the differences between Chavismo and Peronismo today. The Kirchners inherited part of the Peronist legacy rather than building up a movement of their own. By way of contrast, Chávez, Morales and Correa started as political outsiders before building up their own political movements.

Given these contrasts, the view that Chávez, Morales and Correa belong in a class of their own is the one adopted here. This may not have been the case if politics in several other countries had turned out differently. There was significant potential affinity between the three and Peru’s Ollanta Humala and (to a lesser degree) Mexico’s Lopez Obrador who both narrowly failed to be elected to the presidency in their respective countries in 2006. Nevertheless, Chávez, Morales and Correa, and what they represent, have influenced politics outside their borders. They have certainly influenced politics in Paraguay, Honduras and Nicaragua, but the fundamental criterion dividing them from the rest of the region is that our three cases have re-founded politics in their respective countries while the others have not – at least not yet – done so.

Other common factors: High politics and socio-economic issues

What unites the various themes explored in this book is ‘high politics’. In other words, we are mainly concerned with the choices made by political actors and their motivations and consequences. The book does not deal very much with the infinitely disputable issue of the inherent merits of socialism, neoliberalism or social democracy. Rather, we see Chávez, Morales and Correa primarily as (thus far) successful politicians and are interested in what made them so and what they have done with power. This discussion therefore focuses on their political tactics and strategy, political rhetoric, relationship with social movements, economic nationalism and regional economic diplomacy. This is quite a long list; inevitably, for reasons of space, there are also some things that it is impossible to cover.

It is high politics, more than anything else, which unites the experiences of Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador. While common economic, institutional and demographic considerations in the three countries almost certainly do have explanatory power, there are countries in the region whose similar structural features have not – at least not thus far – produced similar political outcomes. The case of Peru is particularly apposite here. Peru has a number of features in common with Ecuador and Bolivia (fewer with Venezuela) but quite a different recent history of politics and government. It would be possible to write about comparative Andean politics (see, for example, Drake and Hershberg 2006; Mainwaring, Bejarano, Leongómez 2006) but that would be a different book.

It is also important not to stretch the extent to which Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador themselves share common characteristics. The governing philosophies of Chávez, Morales and Correa may be very similar but the countries over which they preside are in many ways quite different. Venezuela has less ethnically in common with Ecuador and Bolivia than the latter two countries have with each other and it is economically much more dependent on resource rents from oil. Nevertheless, a brief mention of some relevant structural factors may be useful to some extent. We can then focus better on what we need high politics to explain and what we do not.

One common factor that unites the three (but also Peru) is economic decline over quite a long period of time. Between 1980 and 2000, they seem to have had untypically unsuccessful economic records in the Latin American context. Statistics provided by Sheahan (in Drake and Hershberg 2006: 102), make the point clearly. Most of Latin America did not enjoy good economic times during 1980–2000 but the vast majority of countries did achieve some per capita economic growth. This was in the order of 9% in the region as a whole (Sheahan 2006: 102). However, real per capita income in Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador actually fell – by a significant 6% in Bolivia, 8% in Ecuador and a dramatic 17% in the case of Venezuela.

Economic decline also occurred in Peru by 8% over the corresponding period. While the Peruvian case argues against any general claim that economic decline in Latin American democracies necessarily moves voters towards the left, it may well be the case that we can see some kind of causal mechanism in which sustained economic decline tends to weaken institutions. The Peruvian electorate – like those of Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia – comprehensively rejected the established political democratic parties at times of crisis. Peru elected an outsider to the presidency in 1990. Peruvian public opinion then actively supported the forcible closure of Congress in 1992 and voted for Alberto Fujimori, the president responsible for the closing of Congress, in presidential elections of 1995 and (though more ambiguously) of 2000. In Peru, though, this crisis of institutions mostly benefited the political right.

Nevertheless, at a general level, it makes sense to suppose that negative sum politics can be difficult for any democratic institutions to handle if it persists for long enough. In our three countries, it is not hard to see why some kind of politics of protest should have attracted support. In all of them, economic decline tended to interact with institutional decline. For many years, living standards failed to rise, governments became out of touch and unrepresentative and income distribution worsened. (For country studies of Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador, see Alberts 2008; Buxton 2005; Salman 2006.) Governments were unable to deliver serious reform even as electorates grew impatient, and changes of government did not lead to visible improvements in the lives of majorities.

Moving forward to the current millennium, Chávez and to some extent Morales and Correa later benefited as incumbents from rising commodity prices. Morales also enjoyed the benefits of sharply rising natural gas production, which was actually a result of the policies of his predecessors. Relatively favourable conditions for commodity exporters – particularly oil exporters – have had an effect on politics in our three countries, all of which are exporters of either oil or natural gas (Dunning 2008).

It does therefore seem likely that the economic conditions – decline in the 1980s and 1990s followed by a recovery after around 2000 – probably played some part in the politics of our three countries. However, once we turn to specifics, then the distinctiveness of national factors becomes evident once more. For example, oil-related issues are evidently central to politics in Venezuela, to a much greater extent than in Ecuador and Bolivia, even though the latter two are also exporters of hydrocarbons (Dunning 2008; Karl 1997). The oil-related issues that are most important in Venezuela include (but are not limited to) the political effect of the so-called resource curse and the acute disappointment of expectations following a period of economic overconfidence during the 1970s. Venezuela experienced high rates of economic growth over quite a long previous period (roughly 1925–1980) and Venezuelans during this time were repeatedly told by their leaders and others that Venezuela was a rich country because it had oil. This message was generally believed (Romero 1997) and it made the subsequent sense of disappointment especially bitter.

Conversely, the Bolivian political environment was decisively shaped by the politics of coca, the full economic importance of which is difficult to capture in official figures because of its illegality. However, whereas the problem with oil is that resource rents are paid directly to the government – with the potential risk of mismanagement and frustrated popular expectations – the coca economy is decisively shaped by its illegality. What made this issue decisive was that in the late 1990s the US government pressured successive Bolivian governments to pursue domestically unpopular policies geared towards coca eradication. As a result of US inducements on the one side and the domestic militancy of the coca growers on the other, successive Bolivian governments found themselves between a rock and a hard place. Subsequently, pressures for eradication significantly created a ‘cocalero’ identity in the most affected areas of Bolivia that in turn played a part in creating common political ground among otherwise disparate groups. This common ground provided a basis for internal unity and collective action on the part of radical opponents of the system (Durand 2010). In keeping with the idea of national distinctiveness, there is also a direct historical link between the radical militancy of Bolivia’s tin miners and the current militancy of the cocaleros. Even here, though, we need to be careful about assuming that similar material conditions will produce similar patterns of politics. Indeed, the politics of coca production in Bolivia has so far played out quite differently from coca related issues in Peru (Durand 2008). On this issue, too, we have to deal mainly with separate national stories.

Another important international issue, more relevant to Ecuador and Bolivia than to Venezuela, has been the growing political involvement of indigenous people and their role in radical social movements. This is certainly an important aspect of democratization on which there is much more to be said (Van Cott 2003, 2005, 2008; Yashar 2006). However, the basic demographics of South America put Bolivia and Ecuador alongside Peru in a category quite different to the rest of the region. Van Cott (in Diamond 2008: 34) quotes an estimate that indigenous people make up 71% of the population of Bolivia, 47% of Peru and 43% of Ecuador. No other South American country is more than 8% indigenous. Here as well, then, we have a potential category that includes Peru but not Venezuela.

Indigenous politics also has to be seen in context. In both Ecuador and Bolivia, class inequalities were for many years reinforced by a system of social stratification based on ethnicity and a variable but keenly felt degree of racial discrimination. Even when dictatorship gave way to democracy in Bolivia and Ecuador, the electoral politics that resulted coexisted with informal systems of social exclusion and state bias which indigenous groups resented and, increasingly, found the means to combat.

Notwithstanding the different demographics in Venezuela, it has been claimed that ethnic issues played a significant part in the politics of Chavismo (Herrera Salas 2007). This is a bold claim, which is hard to evaluate fully on the basis of available evidence. It is certainly true that racial thinking exists to some extent in Venezuela (as in other parts of the world) and Chávez’s physical appearance surely plays some part in the way he is viewed across all levels of Venezuelan society. However, the kind of ethnic self-identification that has featured prominently in the construction of social movements in Bolivia and Ecuador clearly does not operate in Venezuela.

Taking these various factors together, there seems to be no completely convincing way of relating the emergence of ‘twenty-first century socialism’ to any set of factors that fit Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador and nowhere else. Yet the purpose of this work is to look at key issues in which Chávez, Morales and Correa have adopted ideas and strategies – and achieved successful outcomes – that are similar to each other and different from the rest of the region. While structural factors will be brought into the discussion where appropriate, the best way of approaching the key question informing this work is to focus on high politics issues which essentially relate to the acquisition of political power and the uses to which it has been and can be put.

This ‘high politics’ focus is however designed to do more than fill the gaps left by weaknesses in other kinds of explanation. The book makes the much stronger claim that the tactical, rhetorical, organizational and institutional aspects of politics not only matter to the general study of politics but are of particular significance in our three cases. It is also claimed that policy successes (to the extent to which these have been achieved) have so far been less important to the continued political strength of our three presidents than policy failure was to the weakening of their predecessors.

The logic of the book

The book starts from the premise that, despite the significant amount of literature that already exists, there is more that can be learned about the viewpoints and strategies adopted by Chávez, Morales and Correa. However, the claims made by the three should not be regarded uncritically. There are both economic and political perils involved in what they have been trying to do, and, despite a clear measure of good fortune, there are aspects of vulnerability and failure in their policy performances. Nevertheless, we cannot discount the fact that these three have come to enjoy significant political triumphs based on sustained majoritarian support. This support is evidently real, and it has made a more autonomous pattern of political leadership more feasible than it otherwise might have been. The reality of this support should not obscure the element of state bias and manipulation that is there as well. The fundamental question for the future of majoritarian democracy in these cases is how far autonomous public opinion can maintain some kind of control over the ambitions of powerful and charismatic political leaders and the scarcely less powerful force of political contestation.

The book is organized around three themes, each of which takes up two chapters. It starts by seeking to explain key factors behind the rise of Chávez, Morales and Correa. How did they achieve national power and why was their mixture of constitutional and extra-constitutional tactics as successful as it turned out to be? In an earlier generation, left-of-centre governments in South America – except for the most anodyne and moderate kinds – were once routinely overthrown or vetoed by the military, and this came close to happening again when Chávez was nearly overthrown by a coup in 2002.

Electoral victory and the absence of a military veto are necessary parts of the explanation for this outcome but not sufficient ones. Confrontational political tactics played a role as well. If Chávez had not launched a failed coup attempt in 1992, he would almost certainly not have been elected president in 1998. If Morales had not (with his allies) used radical tactics of civil disobedience to polarize the political situation and isolate an unpopular but constitutionally elected president, he would probably not have reached the presidency either.

The second chapter looks at similar issues but this time from the perspective of the protest movements. These have proved powerful engines of popular mobilization and encouraged political participation among previously excluded groups, but they have also enabled the emergence of populist leaders with little respect for institutional principles or procedures. The chapter considers whether the mobilizing potential of protest politics is ultimately supportive of democratic values or whether it may lead to the further weakening of already weak pluralist democratic institutions that the cause of democracy would have been better served by strengthening. Given the ambiguities of public opinion, conflicting normative principles are involved in these new kinds of politics and the resulting issues are finely balanced.

The middle section of the book looks at some of the means by which Chávez, Morales and Correa have maintained themselves in power. The discussion adopts the idea of radical populism, both in its ideological aspects and in its organizational ones. The chapter claims that, when appropriately defined, this notion of radical populism does enable us to locate some significant aspects of politics in all three cases. However, we need to bear in mind certain caveats. The populist label needs to be applied carefully. It is not an all-embracing explanation or characterization of everything. It is important to emphasize as well that the radical populist label is not intended to be either belittling or dismissive.

Populism, following Laclau (2006) is defined here as a political strategy based on the discourse of popular unity and the stigmatization of unpopular elites. Populism may correlate with other things, such as economic policies, but these are not part of any definition as such. It should be emphasized too that this is not a work about ‘economic populism’ which is something altogether different. Readers looking to this book for systematic discussion of the economic performance of these governments will be disappointed. Any relationship between populism as understood here and policy is an empirical matter, even perhaps a contingent one. Notoriously, some populist leaders are serious about social reform whereas others are mandate-breakers exhibiting various degrees of cynicism (Stokes 2001).

Following on from a discussion of populism, the book then looks at the institutional means by which the three leaders consolidated their power. This was essentially through the use of constitutional reform via plebiscite. The ultimate objective was to strengthen the presidency and enhance the centralization of effective power (notwithstanding some aspects of greater political devolution). The political contribution of this institutional engineering was to convert potentially transient popularity into a potentially lasting source of power. The chosen formula – calling for a plebiscite for a Constituent Assembly, drawing up a new constitution that strengthened central power, holding a plebiscite to approve the new constitution, and closing the whole issue by means of fresh elections – was largely developed by Chávez. Morales and Correa, both elected several years later, largely followed the pattern. One of the ironies of the process is that plebiscitary tactics were prior to Chávez much more common on the political right than the left.

However, these plebiscitary tactics, though effective, were only possible because the three leaders were popular enough to win plebiscites. Not every president in the region was in so happy a position. It is therefore insufficient to attribute the popularity of these leaders to their radical populism or to their political tactics. This popularity is an empirical fact and not a definitional property of populism itself or a matter of plebiscitary sleight of hand. It is instead something that has to be explained. There is a very old joke about an apocryphal ‘people’s popular party’ whose leaders constantly risk being pelted with tomatoes by a hostile public. It is true to say that populists seek popularity but so, in a democratic context, do non-populists. They simply do so by different rhetorical means.

The final part of the book moves the discussion to broader economic and international policy issues. One chapter has to do with the politics of oil and gas. What this chapter seeks to do is to discuss the policy consequences within a key economic area of some of the political themes discussed in the book as a whole. These include a radical populist tendency to look for ‘others’ to denounce – nothing offers a better target for this than a foreign owned oil or gas company although (as Chávez showed) a technocratically run state oil company can come a close second. Oil and gas policy in both Venezuela and Bolivia also reflects the presidentialization of economic policy making, not so much as any particular ultimate objective as in a political need to be seen to be in control. This chapter looks at key decisions made mainly in Venezuela and also in Bolivia. However, when looking at policy consequences, Venezuelan oil and gas policy matters more and it has taken on a clearer shape than in Bolivia and, still more, Ecuador. Not only has Chávez been in power for much longer, but the Venezuelan oil industry is globally significant (unlike those of Ecuador and Bolivia) and Venezuela is also much more dependent on oil and gas than the other two.

The final chapter deals with a key aspect of regional diplomacy, and at the role played by Chávez in particular in blocking the US-led Free Trade of the Americas initiative, which played such a key role in the Miami Consensus of the 1990s. It also considers the changing balance of diplomatic power within South America in a more general way. Both chapters consider mainly a style of policy making which is confrontational and drama-seeking rather than considered and bureaucratic, and therefore fully in keeping with Chávez’s domestic political style. In some respects, particularly Venezuela’s inability to avoid a decline in its oil production, this has proved costly. However, Chávez’s ability to internationalize effectively – notably his role in the reinvigoration of OPEC and Venezuela’s much higher diplomatic profile within Latin America – has to some extent to be set against policy failures at home, though the resulting balance looks fragile.

Looking ahead, there must be real uncertainties about the future trajectory of politics in all three cases. All three countries remain democracies of a kind but, since the fundamental basis on which these presidents rest is their domestic popularity, they may find themselves very exposed if things start to go wrong. In such an eventuality, they would almost certainly become either more openly authoritarian or weaker or both. Indeed, even as it is, it is not clear that politics in any of the three countries can now be re-institutionalized in an unambiguously democratic setting without some further process of political upheaval. This is something discussed again in the conclusions.

1

THE MILITARY AND THE RISE OF THE LEFT

Chávez, Morales and Correa all reached the presidency through democratic election but did so in far from normal circumstances. Chávez first came to prominence as a coup leader when, as a lieutenant colonel, he led a dramatic but unsuccessful attempt to seize power in February 1992. Although unsuccessful, the coup provided a major shock to the system and played a part in inducing the Venezuelan Congress to impeach the incumbent president Pérez in 1993. There was a further coup attempt – not led by Chávez – in November 1992 and yet another potential coup attempt in 1993. There followed a further period of institutional decline, this time affecting Venezuela’s once-strong party system, before Chávez won the presidential election in December 1998. Chávez himself was then at the receiving end of a coup attempt in 2002 that he only narrowly survived. In Venezuela, therefore, the key crisis events concerned coup attempts, even though none of them actually succeeded.

Morales was and is a civilian. His background is indigenous and he was a coca producer. In 1998, he formed and led a political party, the Movimiento al Socialismo, which opposed the market oriented policies of Bolivia’s elected governments. Morales became one of the main leaders, and the main political beneficiary, of a highly effective campaign of civil disobedience which started to take on momentum in 2000 and led to the downfall of constitutional governments in 2003 and 2005. Morales emerged from this process as a credible presidential candidate and was elected in December 2005. By winning with an outright majority, Morales broke a long historical sequence in which presidents were chosen by Congress after winning only a plurality of the popular vote. Morales has continued to serve as democratically elected president, despite some periods of high political tension, including in August 2008 when the military ignored calls made by some of the right-wing opposition for a coup. In Bolivia, then, we are dealing mainly with military non-support of the civil power at decisive moments. The military in 2003 and 2005 ultimately stood back and let civil disobedience take its course, though in 2008 it did support an embattled constitutional government when some right-wing politicians were calling for a coup. It is also interesting that General Hugo Banzer, who governed Bolivia as a right-wing dictator between 1971 and 1978, later converted himself into a conservative but democratic politician and won national elections in 1997. It was under the former general that Bolivia’s civil disobedience campaign first took off to a significant degree.

Correa is a civilian and a technocrat with a doctorate in economics from the University of Illinois. His first major political experience was in alliance with the anti-Gutiérrez movement that led to the removal of an unpopular president in 2005. Correa served briefly as economics minister in the subsequent caretaker government and used this position to raise his profile somewhat as a presidential candidate in 2006. Even so, he received no more than 22.8% of the vote on the first round (Conaghan 2008) but he was able to mobilize a range of anti-status quo forces to win the second round run-off against the better-known favourite. Correa can best be seen as the main beneficiary of a series of crisis events that involved him only tangentially. These crisis events did however involve the military and included a semi-failed coup attempt in 2000.

All three, then, rose to power from different backgrounds. The events that led to their rise were nationally specific. However, the three political careers do have quite a number of things in common. All were elected in the context of very turbulent political situations – indeed after prolonged political crisis. All three were either rebels or (in the case of Correa) largely unknown figures before they came to power. They are all self-proclaimed socialists, and they radicalized rather than moderated when in power. This was a combination whose emergence was not seriously anticipated by the Miami Consensus of the 1990s.

This chapter looks mainly at the role of the military in shaping these events. A pessimistic set of observers might have expected that the kinds of crisis that led to the rise of Chávez, Morales and Correa would instead lead to full scale democratic breakdown – or indeed that it might yet do so. Yet Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador have so far all consistently met the minimum Schumpeterian criterion for democracy, namely competitive and honestly counted elections (Schumpeter 1950). Even so, the military, and popular attitudes towards the military, also played a significant role in determining political outcomes.

Crises and democratic near-breakdown: A comparative perspective

Before discussing our three cases in detail, it will be helpful to look first at how they fit the broader regional context. In fact, they are not really typical. Most Latin American countries have not seen significant military involvement in politics since the development of ‘third wave’ democracy. The purpose of this chapter is only tangentially concerned with why this should be so. We are concerned more with what happened when the military did intervene, whether directly or indirectly.

It would, though, not be true either to say that our three cases are complete outliers. Within the region as a whole, there is a significant number of countries – essentially Peru, Paraguay, Honduras, and for a time Argentina, together with Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador – in which the military has become involved directly in ‘third wave’ democratic politics. All of these need at least a brief discussion. The cases of Paraguay, Honduras and Argentina are mentioned below while Peru – which is a more apposite comparator for our three countries in many ways – is discussed in some detail later in the chapter.

For several years, essentially between 1996 and 2003, Paraguay went through a period in which elections, civil disobedience and coup attempts continued and interacted. There were elections in 1998 (and then 2003), coup attempts in 1996 and 2000, and the impeachment and criminal prosecution of a president in 1999, following some kind of civil uprising. These events clearly show some kind of (in this case highly conflictive) interactive process at work between personalist military officers, coup attempts and the holding of elections. There were coup attempts but no actual return to dictatorship.

In Honduras in 2009, the military physically overthrew incumbent president Zelaya at the request of the Supreme Court backed by the National Congress. What led this overthrow to be described (by opponents of the process) as a coup was the fact that the military arrested and then exiled Zelaya, while Congress installed a new interim president. The use of the word ‘coup’ therefore relates to the violation of constitutional legalities, including Zelaya’s right to defend himself in court, and not to any suggestion that the military was the prime mover in Zelaya’s overthrow. (As we shall see in chapter 4, there have been a considerable number of examples in Latin America of presidential removal by a hostile congressional majority, sometimes via questionable constitutional means.) The Honduran case fits a broader argument about the military, namely that it may feel a need to intervene when it cannot avoid involvement in constitutional crises but that it then shows a marked reluctance to try to rule as a dictatorship. In Honduras, the overthrow of Zelaya did not prevent pre-planned national elections going ahead on schedule later in 2009. Again, we see a pattern in which military intervention and the electoral process somehow interacted.

In Argentina, the military was restive in the late 1980s (Norden 1996) but has become much more docile since. Some medium-rank army officers, radicalized by their experience of military defeat in the South Atlantic in 1982, rebelled against elected president Alfonsín on several occasions during 1987–9, by which time economic problems were making the Alfonsín government increasingly unpopular. Here, too, military-political activity did not suppress the electoral process but did influence it, in Argentina’s case helping to bring about the ending of Alfonsín’s presidential term a few months before the constitutional term limit in 1989. The military was effectively pacified after Carlos Menem, who was throughout his term a relatively popular president, suppressed a military rebellion in 1990. It has since stayed out of politics, notably remaining on the sidelines during Argentina’s very deep political and economic crisis of 2001–3 (Levitsky 2003). In the Argentine case, military rebels were prepared to put pressure on an unpopular president, but popular presidents were able to control the military. In 2001, the military stayed out of politics and allowed the semi-constitutional removal of an unpopular president by a much more popular Peronist party.

We see some kind of pattern here which will be elaborated further when we look at a further set of comparisons later in the chapter. However, we need first to try to make sense of what we have seen so far, and look at the way that the nature of military intervention in politics has changed since the onset of ‘third wave’ democratization.

Changed patterns of military-political behaviour

Studies of military-political behaviour that were conducted before the arrival of ‘third wave’ democratization mostly concluded that there were multiple paths via which military officers could be drawn into politics (Fitch 1978; Lowenthal 1976; Needler 1964; Nun 1976; Philip 1985; Stepan 1971; Villanueva 1972). Some of these were quite opportunistic. There certainly were politically ambitious officers who welcomed the chance to play an interventionist role, and these included both left- and right-wingers. A lot of the time, in fact, active politics within the military involved competition between highly politicized military minorities. However, less politically minded officers sometimes supported intervention if they saw this as necessary to protect military institutionality (i.e., internal military order and discipline rather than political institutionality) if they saw this as coming under threat. Because the military is inevitably based on notions of hierarchy and obedience, there was also a link in the minds of many officers between intensive social mobilization, ‘subversion’ and military insubordination. Fear of this combination of factors could certainly trigger a coup and what might be called hierarchism explains a lot of right-wing bias in military-political behaviour.

Civilians, too, sometimes invited participation by the military. Intervention could be triggered either by direct invitation (famously called ‘knocking on the doors of the barracks’ (Imaz 1964), or via acts of civil unrest designed to pressure the military to define its position. Anti-government demonstrators in Chile in 1973 notoriously banged empty saucepans. Moreover, once some officers came to believe that others were preparing to intervene in the political process, the logic of pre-emption came into play. For these reasons, while most military interventions in Latin America between 1948 and 1982 were right of centre and authoritarian, there was inevitably a degree of unpredictability in any specific case and some outcomes were surprising.

Today, it seems that top army officers generally avoid trying to impose dictatorship even if they find it necessary to arbitrate institutional conflicts at times of crisis. This reluctance to try to take power outright seems to be less in evidence in the case of middle-ranking officers and officers from the navy and air force. In these latter cases, a coup attempt may be as much a rebellion against the military establishment as against the elected government. It is noteworthy that, of the five coup attempts in our three countries, two were led by middle-ranking officers (Chávez and Gutiérrez) and one was led by a naval officer with air force support (Gruber, in Venezuela, in November 1992). Of the others, the coup attempt in Venezuela in 2002 was the result of a deliberate attempt by the right-wing civilian opposition to provoke a crisis so as to create the conditions that might appear to justify military intervention. Not much is known about the potential coup leadership in Venezuela 1993 but in the event no coup took place.

Coup attempts led either by middle-ranking army officers or by senior officers from the navy or air force, though potentially more radical (because less hierarchical), are less likely to succeed militarily than those led by the army high command because they are more likely to encounter opposition from within the military itself. The military superiors of middle-ranking golpista officers will have institutional and personal motives for remaining loyal to the government. If they are overthrown by their juniors, their military careers are likely to end. Very senior officers have a better chance of purely military success when attempting coups because they should be able to command obedience even in the absence of enthusiastic support. However, under conditions of ‘third wave’ democracy, very senior officers have seemed happier to avoid overt dictatorship, even in cases where they have effectively usurped power – as in Honduras in 2009 and (as we shall see) Peru in 1992.

It should be noted that the discussion so far relates to the military as an organization. Ex-military officers in civilian clothes can sometimes achieve electoral success as individuals. Both Chávez and Gutiérrez were elected to the presidency after having been jailed for leading failed coup attempts. Although they did not meet with as much electoral success as Chávez did, a number of other Venezuelan officers involved in both of the 1992 coup attempts made some kind of transition to electoral politics thereafter (Norden 2003). Outside Venezuela, it may still be relatively unusual in Latin America for former military officers to become credible civilian candidates in elections but it is by no means unheard of. Bolivia’s Hugo Banzer was elected to the presidency in 1997, Ollanta Humala narrowly failed to be elected in Peru in 2006 and even Pinochet retained a significant vote in the Chilean plebiscite in 1988. Prior to the ‘third wave’ of democratization, it was still more common for former military officers to convert themselves into successful politicians than it is today. Examples include Argentina’s Perón, Chile’s Ibáñez and Peru’s Odría. Similarly, Brazil’s Vargas, though a civilian, presided over an authoritarian regime for fifteen years before being overthrown in 1945 and coming back to win the presidential election in 1950.

Explaining military intervention without dictatorship

When trying to explain why the top military leadership is generally reluctant to impose dictatorship, region-wide factors are probably key. It certainly makes more sense to refer to the changed international climate in general rather than just to the role of the US government. The US government vacillated in its response to the Venezuelan coup attempt of 2002, as indeed it has vacillated in its response to other coup attempts in the region (such as Ecuador in 2000). The international community reacted negatively to the Peruvian autogolpe in 1992 but gradually allowed itself to be won over when Fujimori ‘re-constitutionalized’ his regime (Costa 1993). However, while the US has sometimes indicated that it would accept conveniently patched-up deals that violated the national constitution, it could not support the open abandonment of democracy as such. Perhaps as important as the government in Washington, and certainly more consistent, has been the role of various regional and international organizations in discouraging outright military dictatorships (Santa Cruz 2005).

One new concern is that the military and – still more so – pro-government civilians are today much more likely to be subject to reprisals if they threaten or try to use excessive force. Prior to the 1980s, judicial measures against coup leaders or despots were virtually unknown in South America, except to the extent that junior officers and NCOs could face harsh discipline from their seniors for military insubordination. The development of legal accountability for military or political figures directly involved in repression started in Argentina after 1983, proceeded slowly and uncertainly for a time but developed increased momentum during the 1990s (McAdams 1997). The arrest of Pinochet in London in 1998 was an important further step in the development of this process. Today, the military and their civilian allies face real risks of international criminal proceedings, and this can be a real deterrent. The effect of such a change can be to create dilemmas since there are legal risks involved both in overthrowing a government and in using excessive force to support one.

To sum up the argument so far, there seem to be three binding constraints on military political behaviour in Latin America. One is the outright overthrow of democracy and imposition of dictatorship. Since the early 1980s, this has not happened anywhere in the region. The second is that the military will dislike getting on the ‘wrong side’ of public opinion. The third, connected to the second, is that the military dislikes having to use massive force to defend an incumbent government. These constraints do not rule out all forms of military-political activity. They do help us understand what the military is likely to do when it does intervene. Forms of military-political activity that do not violate these constraints, including the transformation of military officers into civilian politicians, remain feasible and can influence the political process.

A Peruvian comparison

We can learn more about this and a semi-military kind or semi-electoral kind of politics by looking at Peru, which in the 1990s was the only major country in Latin America in which there was a full-scale military coup. In fact, Peru between 1992 and 2000 is the nearest that any Latin American country has come to a genuine democratic breakdown under ‘third wave’ conditions.

The Peruvian crisis went through a series of stages. Coming into politics as a complete unknown at a time of hyperinflation and serious insurgency, Alberto Fujimori won presidential elections in 1990 when Peru’s party system – which was never very strong – effectively collapsed. However, Fujimori was elected without a congressional majority and his relations with Congress soon deteriorated (Cotler 1995). Facing an unpromising economic and security situation and fearing possible impeachment, Fujimori with the help of his security chief Montesinos organized a military autogolpe in 1992 that kept him in the presidency while the military closed the National Congress (Kenney 2004). The military had been restive for some time previously and there had been some plotting even before the election of Fujimori (Rospigliosi 2000). In 1992, a decisive weight of senior military officers was persuaded to participate in a kind of political marriage of convenience in which Fujimori’s popularity and standing as legally elected president was combined with the military’s command of force. There was some military opposition to the autogolpe but this did not prove effective.

The autogolpe