Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Honford Star

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Kang Kyeong-ae (1906-1944), one of Korea's great modern authors, wrote her stories during the Japanese occupation of Korea. Kang's work is remarkable for its rejection of colonialism, patriarchy, and ethnic nationalism during a period when such views were truly radical and dangerous. With an expert commentary by Sang-kyung Lee and beautifully translated by Anton Hur, this collection of Kang's work displays her sensitivity, defiance, class-consciousness, and deep understanding of the oppressed people she wrote about.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 407

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

praise for the underground village

‘The Underground Village: Short Stories by Kang Kyeong-ae anthologizes the major short fictions by Kang Kyeong-ae, one of the most innovative writers of colonial Korea, rendering them into natural and graceful English. Kang’s stories of poverty and hardship, often featuring female protagonists and set in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, cross multiple borders, those of race, gender, geography, culture, ideologies, and literary schools, thus forcing us to reconsider our notions of feminism, Marxism, modernism, socialist realism, and “Korea”.’

—jin-kyung leeAssociate Professor of Korean and Comparative Literature,

University of California San Diego

‘Kang is an important representative of Korean women during the Japanese colonial era; a rare reflection of lower-class women’s voices. Moreover, Kang brilliantly captured the zeitgeist as a writer who witnessed participants in armed struggles against the Japanese, testifying to their suffering and validity, and she was able to convey all of this to colonial Korea directly under Japanese rule.’

—sang-kyung leeCo-editor of Rat Fire: Korean Stories from the Japanese Empire

THE UNDERGROUND VILLAGE

short stories by kang kyeong-ae

Translated byanton hur Introduced bysang-kyung lee

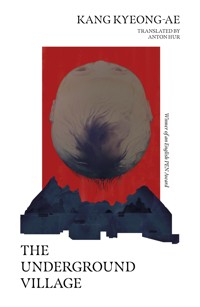

This translation first published by Honford Star 2018honfordstar.comTranslation copyright © Anton Hur 2018Introduction copyright © Sang-kyung Lee 2018All rights reservedThe moral right of the translator and editors has been asserted.ISBN (paperback): 978-1-9997912-6-1ISBN (ebook): 978-1-9997912-7-8A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.Cover illustration by Dal SangBook cover and interior design by Jon GomezPrinted and bound by TJ InternationalThis book is published with the support of the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea).This book has been selected to receive financial assistance from English PEN’s “PEN Translates” programme, supported by Arts Council England. English PEN exists to promote literature and our understanding of it, to uphold writers’ freedoms around the world, to campaign against the persecution and imprisonment of writers for stating their views, and to promote the friendly co-operation of writers and the free exchange of ideas. www.englishpen.org

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

Manuscript Money

Salt

Peasants

The Authoress

Darkness

The Man on the Mountain

Anguish

Opium

Sympathy

Father and Son

Mother and Son

Tuition

Real and Unreal

Blackie

Break the Strings

The Firing

Vegetable Patch

The Tournament

The Underground Village

TRANSLATOR'S NOTE

INTRODUCTION

One of the things which makes Kang Kyeong-ae (1906-1944) unique among Korean women writers of the era, most of whom lived in the cultural hub of Seoul, is that all her prose fiction was written in Jiandao in Manchuria, China. Although it was on the periphery of Korean literature, Jiandao was at the time the centre of an armed struggle to overthrow the Japanese colonial rule of Korea (1910-1945). This meant that while most other authors in Seoul also worked as reporters for magazines or newspapers and were central members of literary circles, Kang had vastly different preoccupations. Living in Manchuria and devoting herself to literary creation imbued Kang with an artistic and political tension which enabled her to make a greater artistic achievement than any of her contemporaries.

*

Kang Kyeong-ae was born to impoverished peasants on 20 April 1906 in Songhwa County, Hwanghae Province, in what is now North Korea. However, following her father’s death and her mother’s remarriage, Kang grew up in Jangyeon County, also in Hwanghae Province. Although her stepfather had money, he was an elderly, disabled man, and Kang’s mother is said to have been a veritable servant to him. At around the age of seven, Kang taught herself to read hangul, the Korean alphabet, from a copy of the classic Korean novel Tale of Chunhyang (Chunhyangjeon) that happened to be in the house. She went on to read other traditional prose fiction in hangul, and elderly neighbours vied with each other to take her home to have her read similar works out loud, buying her sweets as recompense. The girl was thus given the epithet ‘Acorn Storyteller’ in her neighbourhood.

As a result of her mother’s pleas to her husband, Kang was able to enter primary school in 1915, already past the age of ten. The family was unable to pay expenses such as tuition fees and money for stationery, and Kang had to study while feeling ill at ease, even fantasizing about stealing her classmates’ money and possessions. In 1921, with help from her brother-in-law, Kang entered Soongeui Girls’ School (present-day Soongeui Girls’ Middle and High Schools) in Pyongyang. A Christian institution, this school was dubbed ‘Pyongyang Prison No. 2’ due to its strict dormitory regulations. In October 1923, during Kang’s third year, the students staged a class boycott in protest against both the strict dormitory life and the American principal who had banned ‘superstitious’ visits to ancestral graves during Chuseok, the mid-autumn full moon festival. Kang was expelled due to this incident, and she reportedly went to Seoul where she studied for one year at Dongduk Girls’ School (present-day Dongduk Girls’ Middle and High Schools).

While a student in Seoul in May 1924, Kang published a poem titled ‘Autumn’ (‘Ga-eul’) under the pen name of ‘Kang Gama’ in the literary magazine Venus (Geumseong). However, Kang soon withdrew from Dongduk Girls’ School and returned to her hometown of Jangyeon in September 1924. Back home, Kang found her mother impoverished and was tormented by the silent criticism that an intelligent student had come back without any accomplishments. As a result, Kang went to China and worked as a teacher for two years in Hailin, northern Manchuria.

Hailin in 1927-1928, during Kang’s sojourn, saw the Manchurian Bureau of the Communist Party of Korea (Manju Chongguk Joseon Gongsandang) expand their power after colliding with ethnic Korean nationalists represented by the New People’s Government (Sinminbu), and Kang would have directly witnessed the serious ideological and physical conflicts between the two groups. Life in Manchuria at this time was particularly ruthless due to the secret ‘Mitsuya Agreement’ between Manchurian warlord Zhang Zuolin and Mitsuya Miyamatsu, the head of the Bureau of Police Affairs in the colonial Government-General of Korea. This agreement promised monetary reward for those reporting ethnic Koreans who possessed weapons or were involved in anti-Japanese activism, and resulted in both Manchurian warlords and Japanese imperialists expelling or arresting ethnic Korean independence activists – nationalists and communists alike. Additionally, under the perception that imperial Japan was invading the area with ethnic Korean peasants as spies, Manchurian warlords persecuted ethnic Koreans, demanding they pay money and become naturalized citizens of China. In such a situation, ethnic Korean nationalists and communists often suspected and even killed each other, and the lives of many ethnic Korean peasants who had settled in the area were destroyed. It is in this context that Kang came to harbour communist sympathies and to maintain the belief that for poor Korean peasants there was no difference between compatriot landlords back in Korea and non-Korean landlords in Manchuria.

Leaving Hailin in 1928 and returning to her hometown of Jangyeon, Kang played a key role in the establishment of the local branch of the Society of the Friends of the Rose of Sharon (Geun-uhoe) in 1929, and she founded Heongpung Night School, an academy for children from impoverished families where she taught classes on literature and started writing fiction in earnest. This period was also when she met future-husband Jang Ha-il, a graduate of the Suwon College of Agriculture and Forestry who had been appointed to the Jangyeon County Office. Living far away from his wife, whom he had been made to marry at an early age, Jang had come to Jangyeon together with his mother and lived in Kang’s house as a tenant.

As a writer who was involved indirectly with KAPF (Korea Artista Proleta Federacio; Korean Proletarian Artists Federation), Kang would have been influenced by the ‘December 1928 Resolution’ – the decision adopted by the Communist International on the reorganization of the Communist Party of Korea. This document argued that the party must discard intellectual-centred organization methods, organize labourers and indigent peasants by infiltrating factories and agrarian villages, and isolate ethnic reformists. While many Korean writers criticized these methods and the document, Kang did not and was consistent in her political attitude.

Therefore, the essays that Kang published after her return to Korea from teaching in Hailin in northern Manchuria and after the ‘December 1928 Resolution’ exhibit a level of awareness completely different from that in the short sketch-like poems that she had published earlier. For example, in October 1929 Kang published a criticism of the popular author Yeom Sang-seop, who was dubbed a ‘centrist’ at the time, and in February 1931 Kang published a rebuttal of Yang Ju-dong, a self-styled ‘syncretist’.

As the romance between Kang and Jang progressed, the couple invited friends to a simple wedding ceremony before relocating to Longjing in Jiandao around June 1931. In Jiandao, Jang worked as a teacher at Dongxing Middle School (present-day Longjing Senior High School) and Kang started to publish her fiction while taking care of their home. Jang was a good reader, understanding Kang’s literary world, always being the first one to read her works, engaging in discussions, and providing advice. Indeed, he was a devoted husband who did his utmost to treat Kang’s chronic illnesses.

Jiandao in the early 1930s was a land of war. While the Chinese people engaged in a fierce movement against both feudal landlords and warlords, Japanese imperialists incited the Mukden (or Manchurian) Incident in September 1931 and established the puppet state of Manchukuo in March 1932, before proceeding with mass-scale operations to eradicate ethnic Korean independence fighters. In the process, many people lost their homes, families, and lives. To flee such chaos, Kang left Jiandao and returned to Jangyeon around June 1932, then went back to Jiandao around September 1933. Although she did travel to Seoul and Jangyeon from time to time, from this point she lived in Jiandao, maintaining the household while steadily publishing her fiction.

In 1939, Kang returned to Jangyeon for the final time because her health had started to worsen in the previous year. In the end, she died on 26 April 1944 due to aggravated illness aged thirty-eight.

*

The class consciousness that Kang embraced in Hailin and the atrocities and popular resistance that she witnessed in Jiandao became archetypal experiences for Kang’s literary activity. Though she produced nearly all her writing in Manchuria, she never mentioned the Japanese puppet state’s specious propaganda, for example slogans such as ‘concord among five ethnic groups’ (Han Chinese, Manchurians, Mongols, Koreans, and Japanese) and ‘paradise under royal government’ (rule by the puppet emperor of Manchuria). Kang’s works are instead infused with the desolation in people’s lives caused by the creation of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo, the ruthless reality of being ruled by soldiers, and the strenuous efforts required to protect one’s individual and social life against such forces.

Kang’s early fiction gives insight into the lives of Korean peasants living in Jiandao who had moved to Manchuria because life in their home villages had become unsustainable, and how compatriot landlords back in colonial Korea and non-Korean landlords in Manchuria were equally oppressive. For example, ‘Break the Strings’ (Pa-geum; 1931) recounts how a young ethnic Korean couple tormented by family and romantic problems comes to devote themselves to the armed anti-Japanese struggle in Manchuria, and ‘The Authoress’ (Geu Yeo-ja; 1932) clearly exhibits a class consciousness that transcends nationalism. Thus, the starting point of Kang’s literary career clearly displays a criticism of the Korean bourgeoisie which continues throughout her writing. This is also shown in the character of Sin-cheol in her sole novel The Human Problem (In-gan Munje; 1934. Published in 2009 by Feminist Press as From Wonso Pond); an untrustworthy university student who finally joins the anti-labour camp after wavering between peasants/labourers and landlords/capitalists.

Kang thus established class problems rather than ethnic problems as the main conflicts in her fiction overall and, based on them, penned many works reflecting proletarian internationalism. In the case of ‘Vegetable Patch’ (Chae-jeon; 1933), all personages are Chinese and class problems among the Chinese are addressed. While ‘Salt’ (So-geum; 1934) and ‘Opium’ (Mayak; 1937) likewise feature Chinese landlords and capitalists, their evil deeds do not take on particularly ethnic characteristics. In other words, these figures oppress Bongyeom’s mother (‘Salt’) and Bodeuk’s mother (‘Opium’) economically and sexually not because they are Chinese but because they are wealthy males. Continuing with the theme of class, Kang published ‘Cape Changsan’ (Changsan-got; 1936), a Japanese-language short story not included in this volume that focused on proletarian internationalism more clearly and specifically than any other proletarian literary work by other KAPF writers. Although internationalism first emerged among KAPF writers around 1927 and was highlighted again before and after 1931, it led to no noticeable achievements. In contrast, ‘Cape Changsan’ is a significant demonstration of Kang’s resolute maintenance of internationalism even in 1936.

Kang strove to depict the lives of impoverished ethnic Koreans living in Jiandao, the oppressors making such lives unbearable, and the anti-Japanese activists fighting against these forces, so changes in the situation in the area had a strong effect on her writings. Works such as ‘Mother and Son’ (Moja; 1935), ‘Anguish’ (Beonnoe; 1935), and ‘Darkness’ (Eo-dum; 1937) portray the gradual defeat and retreat of ethnic Koreans’ armed anti-Japanese organizations in Jiandao following their fierce resistance in the early 1930s. These stories also display the struggles and undaunted spirit of the families left behind, and the ethnic Korean betrayers who treated them with hostility. At this time, under increasing militarism by the Japanese rulers, writers in colonial Korea swerved from earlier topics of ethnicity and class and began to sensitively portray poverty and emotions in everyday life. Kang’s works, too, reflected such a tendency. Her ‘The Underground Village’ (Jihachon; 1936) depicts extreme states of poverty in exhausting detail, making it impossible for readers to disregard the harsh reality despite a possible desire to do so. In addition, Kang ceaselessly produced writings that focused on and reminded readers of the fates of anti-Japanese independence activists in Jiandao. A representative work in this vein, ‘Darkness’ (1937) presents the younger sister of a young Korean man executed by the Japanese authorities for his involvement in a political incident, about which everyone in colonial Korea maintains silence. In addition to such doses of reality, Kang also published ‘Manuscript Money’ (Won-go-ryo I-baeg-won; 1935), which directs criticism against intellectuals such as herself.

*

For a woman to become a writer in the Korean colonial era, she needed the economic means to receive at least a secondary education and a network through which she could publish her writings. In this respect, Kang’s formative background differed from other female authors. An unhappy home environment and extreme poverty gave Kang a different perspective. Male writers with such backgrounds were not hard to find, but in the case of women, opportunities to overcome such poverty and to establish themselves in the literary scene were extremely rare. In impoverished environments, most women were not provided with any education nor could they possess the time to establish their identities and the time and space to produce writing. Consequently, they were unable to leave lasting records. In this respect, Kang is an important representative of Korean women during the Japanese colonial era; a rare reflection of lower-class women’s voices. Moreover, Kang brilliantly captured the zeitgeist as a writer who witnessed participants in armed struggles against the Japanese, testifying to their suffering and validity, and she was able to convey all of this to colonial Korea directly under Japanese rule.

Sang-kyung Lee

Professor of Modern Korean Literature

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology

THE UNDERGROUND VILLAGE

Manuscript Money

My dear little K,

I received and read your last letter with gladness. I’m happy to learn that you have strengthened somewhat since I last heard from you. What can be worth more than good health?

Dearest K, you write that with the prospect of graduation, you feel dread rather than joy, hopelessness rather than hope. I understand. With everything that is going on in the country, of course you feel that way. But you must also seek a new awakening amidst the dread and despair. You must discover a new path that burns with joy and hope.

Dearest K, I feel that I still lack the knowledge to express in simple sentences, as you have asked me to, my philosophy on love and marriage. But I shall write down the whole of what is going on in my life and the whole of what I feel from that life in my rough and unlearned sentences. You’re a wise soul, so please discard what you don’t need and use what you can.

Dearest K, I don’t know if you’re aware of it, but for serializing a novel in the newspaper D, I’ve been paid two hundred won in manuscript money. This is the largest sum I’ve ever had in my life. The sudden headiness that came from it made me imagine all sorts of things.

Dearest K, I’m sure you’ve already realized this about me … I grew up in an insolvent household, and things did not get better as an adult. My brother-in-law helped me obtain what mouse’s portion of learning that I do have. As a child, I never got to own a new dress with colours dyed into it. Instead of rice, I only had boiled millet to eat. I never had proper school supplies when I was going to school. At the beginning of the school year, I would cry and cry because I could not afford any textbooks. I could only manage to get a hold of some old ones, and oh how my lack of paper or pen made my small heart tremble!

Dearest K, I still remember it all very well. I was in the first grade. We were taking final exams the next day, but I had nothing to write with. In my desperation, I stole some implements from the classmate sitting next to me, and can you imagine the scolding I received from my teacher? And the taunts from my classmates: ‘Dirty thief! Dirty thief!’ My teacher, with his terrifying stare, detained me in class instead of letting me go out for recess. I had to keep my arms raised and stand silently by the window. Outside, my classmates were busy making a snowman in the playground, their hands clapping with joy. Even as I stood there in punishment, the sight of the snowman’s mouth and eyes were so funny that I would go back and forth between giggles and tears.

Dearest K, the innocent child that I used to be was foolhardy enough to think of taking someone else’s things, but once I reached middle school I could not bring myself to do so, no matter how desperate I felt. With the money coming from my brother-in-law, I could just barely cover food and my monthly tuition. Sometimes there wasn’t enough for my tuition either, and I could not look my teachers in the eye or ask questions about things I didn’t understand in class. Naturally, I became listless and stupid. It followed that I couldn’t make a single friend. I was so lonely that I came to depend on God, and every night I would go into the dormitory chapel and cry as I prayed. The suffering, however, did not disappear, and it only grew by the day and month.

Meanwhile, my classmates had parasols, new skirts and jackets, knitted scarves and cardigans, and watches. It all seems so silly now, but I envied them so much that tears would come to my eyes. Whenever I saw a classmate knitting a scarf with soft, fluffy yarn, I would wrap the thread between my fingers and my vision would cloud with tears. What that feeling of yarn was like to a schoolgirl! Whenever my husband would ask, ‘How is it you can’t even knit a cardigan?’ and glare at me, I would think back to my schoolgirl days and feel the same jolt to my belly that I felt back then as I touched my classmate’s yarn.

Dearest K, let me tell you about one summer long ago. My classmates were busy shopping in preparation for their return home. In my day there were no synthetic fibres, and everyone prepared ramie skirts and jackets that were as light as dragonfly wings, and they each bought a white or black parasol. I was beside myself and didn’t know what to do. More than anything else, I ached for a parasol. Nowadays, even the salt seller’s wife has a parasol, but back then you couldn’t call yourself a schoolgirl if you didn’t have one of those things. It was as if the parasol were a wordless, exclusive symbol for female students. The silly girl that I was, I simply couldn’t face returning home without a parasol. I ended up crying over it all the time. My roommate must have caught on and wanted to mock me; she managed to procure for me an old, broken parasol from somewhere. I was overjoyed. But I couldn’t find it in my heart to jump up and take it. As I sat there in my awkwardness, my roommate cackled and left the room. As soon as she left, I grabbed the parasol and opened it, but it was broken and ripped in every way. An inexplicable rage and sadness seemed to rise up and seize my throat. But I could not throw that parasol away!

Dearest K, I seem to have wandered too far off the path. That ought to have been enough to give you an idea of what my past was like … I’ve rustled up these old memories, which I hate dwelling on, because I wanted to talk about my present. But you see, even before I received the manuscript money that I mentioned before, I would lie awake for a long time at night thinking about what I would do with the money. It embarrasses me to think about it now, but I thought, First of all, because it’s winter I’ll get a fur coat, a scarf, and shoes … The gap between my teeth is too wide, so I’ll get a thin gold filling, I’ll get a thin gold ring, maybe a watch … No, my husband will have something to say about that. But it’s money I made on my own, what objection could he possibly make? If I don’t get anything now, I’ll never get to own a gold watch. Just grit your teeth and do it. And get your husband a new suit; his old one is falling apart. My husband wouldn’t approve, but I decided I was going to put my foot down. Then the day came when I held my manuscript money in my hand.

Dearest K, my husband and I were so happy we didn’t know what to do with ourselves. Gazing into the lamplight that seemed especially bright that night, I asked him, ‘What should we do with the money?’ just to hear what he’d say. My husband sat silent for a moment and spoke as if to himself: ‘Funny how for people like us, having money is more agitating than not having it … Well, as long as we have it, we should spend it. The most urgent thing would be to get Comrade Eungho a doctor …’

These unexpected words darkened my sight. I was silent. The face of my husband, who was looking at me, suddenly seemed that of a dog and his eyes that of a bull.

‘And then Hongsik’s wife. It’s up to us to take care of them this winter. What else can we give?’

I did not want to hear what he had to say. I turned my head and stared at the wall. Of course I pitied his Comrade Eungho and his friend Hongsik’s wife, and before this money had come to us I had wanted to help them as much as we were able to, but once the two hundred won was in my hand, those thoughts disappeared without a trace. I couldn’t help feeling that way.

My husband, who had noticed my expression, glared at me for a while and said in a rough voice, ‘So how would you rather spend the money?’

This question forced out my suppressed tears. I found my stubborn husband more frustrating and pathetic than I had ever known him. More than anything else, he had never given me so much as a simple wedding ring when we married, or ever bought me a pair of shoes. Of course, this was because he had no money, and it wasn’t as if I didn’t understand that. But this money was not money he had earned. Wouldn’t the rightful thing for him to offer, then, have been to use this money, obtained by my own effort, to buy the wedding ring that I had so longed for, or buy me a pair of shoes?

But this dunce of a man could not have had such thoughts in mind. This more than anything else was what made me resentful. The shoes I’m wearing now are from a trip to Seoul a few years ago when I went to be treated for tympanitis; my husband’s friend Kim Kyungho kept pressing me to take them, an old pair his wife used to wear. Think of how bad my shoes must’ve been for him to insist so. I cannot tell you how ashamed I was. Anyone would’ve felt the same way, and who would want to wear shoes that someone else had worn? But when I looked down at my old shoes, I couldn’t bring myself to refuse him. I examined the proffered shoes carefully and found no holes. I did begin to want them a little then, but I was worried about what my husband would say. I sent him a letter the next day. A few days later he wrote a reply, giving me permission. I wore those shoes, but whenever I looked at them I could never quite erase my first feelings of shame.

That night, the night I held my money in my hand, the shame I felt back then welled up again in my throat. I couldn’t help sobbing. I began crying with my mouth open, like a child.

My husband bolted upright and slapped my cheek so hard I could hear a ringing in my ear.

Tearfully, I screamed at him with all my might. ‘How could you … how could you hit me!’

I jumped back at him. My husband flashed his tiger-like eyes and struck a blow to my head, knocking down the lamp with a loud crash. The smell of kerosene flooded the room.

‘Kill me, why don’t you just kill me!’ I shouted at him as loud as I could. I felt like I was ready to be done with him.

Fuming, my husband said, ‘Even a hundred deaths is too good for you! You think I don’t know how you feel? I see that making a little money on your own has made you forget your own husband. You disgraceful wench, get out! Take all that money and go back to your mother’s house tomorrow, I can’t live with a disgraceful wench like you. So, you just want to be another one of those “modern girl” tarted-up whores? Oh yes, you high-and-mighty literary types, that’s what you all end up becoming! Hah! I don’t fancy myself as fit to be the husband of such a high-and-mighty literary eminence. I suppose you want to fry and broil your hair like those hussies, slap some flour on your face, put on a gold watch and a diamond ring and a fur coat, and stand on some stage sighing, “Ah, the proletariat”? Get the hell out!’

He grabbed my hand and pulled me after him. He pushed me out the door.

Dearest K, I cannot tell you how cold the northern country’s wind is. It’s been four years since I came here, but I have never experienced winds as biting as I felt that night. The whole world seemed to be made of ice. Just looking at the moon made my eyes cold, and although I could see the moon clearly in the sky, powdery snow blew in the harsh, whistling wind. The snow was so prickly against my flesh it was as if a sharp knife was piercing my skin. I stood with my arms wrapped tightly around me.

My mind was fit to burst with all the thoughts running through it. What was I to do? I reached into my swirling mind and took up one thought at a time. The first thought I grasped was that I couldn’t live with that man anymore. You couldn’t pay me enough to live with him! But then what was to become of me? Should I go back home? Home … I imagined the faces of the people and their taunting: That wench came back, of course she would, who could stand to live with such a hussy? I imagined the sorrow on the face of my mother. I cringed. Go to Seoul and get a job at a newspaper or a magazine? Seeing how women journalists tended to degenerate into flirts, I realized I would only fall into similar disrepute. Then where to go, what to do? Go to Tokyo and further my studies? Using what money? Considering my situation, the only study I would be engaged in would be how to be a fallen woman. When I came to this conclusion, I felt as if I were turned away by the world, that no matter where I went, no one would take me in. I felt that aside from the fuming tiger sitting in that room, no one in the world would hold my hand.

Dearest K, is this love? But what else could it be? I started to shed hot tears again. At the same time, the tiger-man’s words came back to me. I thought of poor Hongsik’s wife and how young and vulnerable she was, and of Eungho’s face that was no more than skin and bone at this point. The mother and son who had trembled as they sent him off to prison! Moaning Eungho, who came out of prison with heart disease! The two hundred won in my hand … Only this could save them. My own body was still healthy. And what else could all the things I wanted be but vanity?

I suddenly realized I had been dreaming a dangerous dream.

Dearest K, what’s the use of a gold watch or a gold ring or a fur coat for someone like me? If I could use the money to save the life of a comrade, how right it would be if I did so. And if he is my husband’s comrade, does that not make him my comrade, too? I ran back to the door.

‘Husband, I was wrong!’

The door swung open. I rushed inside and hugged him. ‘Husband, I was wrong. I won’t be, ever again …’ Loud sobs came forth from my throat. But please know that these sobs were very different from the sobs before.

Dearest K, my husband sighed and caressed my head.

‘It’s not that I don’t know how you feel. But while you only have a single skirt and a single jacket, you are not naked. You are clothed. You haven’t the slightest care in the world. But look at Comrade Eungho, or Hongsik’s wife. As long as we have money in our hands, we cannot let our comrades die of sickness or starvation! We cannot let this money turn our heads. Even I felt different from the man I was before that money appeared.’

My husband fell silent. Apparently, he had also been thinking while I was gone, and I realized that his earlier anger had been his attempt to control his own upsetting thoughts and guilt. It made me more determined than ever as I felt a hot fire take hold in my heart.

‘Husband, let’s buy a set of cheap clothes for both of us and a sack of rice and some wood, and give our comrades the rest! We’ll soon make more money on our own.’

My husband swept me into his embrace and said, ‘Good thinking!’

Dearest K, I’ve gone on and on at the risk of boring you. I know that with graduation approaching, you’re dreaming all kinds of dreams. Even those dreams, of course, have their time and place in our lives, and I do not chide you for having them. But someday, you have to step out of those dreams and see reality for what it is.

Look at the suffering of the people outside of the city! Are there not tens of thousands of them turning away from their beloved homelands and running away here to Manchuria? And who will clothe them and feed them once they are here? They come in the hope of finding something better than what they left behind. But one woman becomes a kitchen slave, while another is kidnapped to become the concubine of a rich man, each crying an endless lament as they wander these wide flatlands. But it isn’t just the people of the three provinces who suffer so. Wasn’t it not long ago that the people of Ulleung Island had to make landfall en masse at Wonsan? Did you know that the poor of Korea – no, that the great masses of the poor of the whole world live in the borderlands between life and starvation?

Dearest K, here in Jiandao, the subjugating force has swept in, and the people tremble with fear at the sound of guns and swords. The farmers cannot farm or go to the mountains to get wood, so they migrate to the relatively safe zones of cities such as Longjing or Gukja, but what would they do for food when they get there? A dog’s life is more valuable than a human’s in a place like this.

Dearest K, you may despair because you cannot move on with your education or create a sweet home for yourself. But close your eyes for a moment and think of how meaningless such despair is. Even if by chance you managed to achieve what you wanted and more, it would only be a moment, and you would return to be where the rest of us are. What will you do when that happens? Take your own life?

Dearest K, you’ve gained an impressive amount of knowledge from sitting at a desk, more than enough! Now is the time to obtain real knowledge through action. You must work to increase your societal value. If you neglect this societal value for the sake of concentrating on increasing your exchange value, you will become another failure. I am not saying you are a product or a thing, quite the opposite. But these are the two ways that we as human beings create our character in this world.

Which will you choose?

February 1935

Salt

Peasants

Word came that the Chinese landowner Fang Tong had come to the village.

The woman’s husband took his good overcoat down from its peg and went out the door. The woman could not help being agitated at the sight of her husband disappearing into the distance. Was it really Fang Tong this time? Or the vigilantes again, luring her husband out with a lie? She wanted to cry. Her husband put up with their terrorizing day after day without a word of complaint. It broke her heart. And there he went again, into who knew what sort of danger! She sighed. There was nothing to be done for poor people like them; the only way out of their suffering was death. What could they do except die? She found herself scratching at the wall in agitation. She looked down at her fingernails, cracked and ugly. It was so easy to be killed, yet so difficult to die. Such was life.

Years ago, they had been forcibly driven from their homeland without much more than a basket of goods to their name, and it had felt as if they faced a voyage over a vast ocean towards certain death. At least they managed to rent a patch of farming land from a Chinese landowner, but Chinese soldiers constantly threatened their lives, and the woman and her husband only survived from day to day. Every morning when they set out for the fields, they looked towards the sky and prayed they would be safe.

The soldiers, unable to survive on their pay, went around extorting the peasant farmers. This had gone from happening rarely to being a common occurrence, often in broad daylight. The peasants realized they needed to prepare bribes of money and rice if they wanted to live and had them ready even if it meant going hungry. Then the communists came, which scared the landowners and soldiers off into the city, forcing the soldiers to limit their forays into lands unoccupied by the communists. But when the communists were driven out, the militia arrived.

The woman continued to stare at her fingernails and thought about the many times she had almost died at the hands of Chinese soldiers. That she was alive today was a miracle. She looked up. Her husband was already out of sight; she gazed at a fluttering banner above a distant wall and wondered whether he had reached the next village yet. The anxiety that she had forgotten for a moment filled her heart once more. Her husband had told her he had already paid the vigilantes, so it may be true that Fang Tong had come. It was planting season; it made sense for him to visit. But if he were here, her son Bongshik, who was away, would miss Fang Tong, and Bongshik would not be able to bring back his share of the crops. She kept staring at the faraway wall. Her husband and some other peasants had built it over a period of a whole year. It looked like the fortress walls of their old home.

The wall reminded her of a night five years ago. Chaos had erupted, the sound of guns and shouting coming from all directions. They had hid in the foxhole they had secretly dug near the kitchen hearth. When they emerged days later, Fang Tong had fled, his family slaughtered. Fang Tong went on to buy a house in Yongjing, take another wife, and sire more children, ending up living almost exactly as he did before.

Since Fang Tong fled to town, the house the woman was staring at now belonged to the militia. It was their banner that flew and their guard who stood watch.

She looked elsewhere into the distance. The fields were flooded with sunlight, and birds flew high and unfettered in the blue sky. When would she and her husband get to have land like that? She sighed and stared out at the land they had managed to purchase, a plot on the red mountain. They had tamed the harsh earth of the slope, and now it was arable, but they could not plant anything other than sweet potatoes for the time being.

They could try planting millet, maybe sorghum …She did not mean to, but she began thinking of her homeland again. Her field by the young pines that brushed her knees! Her coffin would be pelted with soil before she forgot that field! How every crop took root in it and thrived! That bastard, she thought as she imagined Old Man Chambong walking up to that field. Her heart throbbed, and her hands and feet trembled. She tried with all her might not to think of her homeland, to keep from flying apart in anger. She found herself standing in the yard and listening to the loud twitter of the sparrows hopping on a pile of hay in the corner.

She turned and went back into the house. Everything in the room called out for her touch. She took up the broom and swept the floor. She caressed the holes in the straw mat as she thought of how they had to have a good life and show that horrible Old Man Chambong … She held back tears. No matter how determinedly they worked the land, their only rewards turned out to be hunger and poverty. What a fate this was, and how cruel was it that God blessed some but cursed others! She carefully swept each room. A sweet potato rolled away from her broom. She picked it up, put it in a basket of them, and started to snap off their sprouts. Most of the peasant houses had the kitchen and the main room in the same space, with a cauldron installed in the corner. She prepared her food beside it. When they first arrived, more than anything else she hated the houses, which felt like caves or cowsheds at best. There was nowhere for her to go when they had a visitor, so she had no choice but to sit while silently facing the guest. But now the presence of a male visitor did not bother her, and the house was more or less tolerable. They never forgot to keep a secret foxhole dug near the mouth of the earthen oven. Whenever they heard gunshots, the family would leap into the hole and stay inside for days on end. They kept their clothes and crops in it, taking out what they needed for their daily lives. They had to do all of this because of the soldiers and the bandits.

She finished handling the sweet potatoes and started sorting through the red beans. The sound of the beans bouncing and rolling soon echoed through the quiet house. Her eyes felt tired, and the sparrows grew louder. She began to think. If they were going to start sowing tomorrow, they needed rice for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and if Bongshik did not meet Fang Tong then he would not be able to bring the rice, but he ought to bring home the other food for side dishes …

Her thoughts faded as she grew sleepy. She rubbed her eyes and went outside. Her eyes came to rest on the hardened bricks of fermented bean paste hanging from ropes on the wall. That’s right, she needed to hang up the rest of the bricks. She brought out a basket of the blocks and started hanging them one by one outside the door, brushing the dust off the older ones and lifting each of them from the wall for inspection. She should make some soy sauce and a jar of chilli paste … but then, she would need some salt …

She sighed and sat down, thinking of home once more. They used to brush their teeth with salt because it was so common … One could flush out an upset stomach with just a handful of salt … Compared to some of the things they had had to do without since their banishment, salt seemed like such a small thing, but she had cried many times over their lack of it. Twenty won and ten jeon for a mal of salt! A peasant farmer could never afford an entire mal, buying it instead in smaller packets. They could only afford to preserve things whenever they had some salt, and when the bean paste would rot instead of fermenting they had to make do with the sparsely-seasoned preserves, but because the preserves were so bland, any dish she made from them would be bland as well.

During meals, her habit now was to look closely at her husband’s expression and feel as if she were at fault. Her husband never said a word, but there were times when he would take a bite and grimace, and resignedly put down his spoon. She would feel the rice turn to sand in her mouth, put her spoon down too, and look away. Not even able to serve up a hearty broth for her husband who came home drenched and stinking of sweat and hard work … she was worthless! Could she truly call herself a wife?

Sometimes, her husband would dump a spoonful of chilli flakes into his bowl to stimulate his appetite. His eyes would tear up, their capillaries fit to burst, and beads of sweat would form around his mouth. Why are you adding so much dried chilli, she would almost say before catching herself. And here she was, responsible for the family’s meals … what was she to do?

She sighed again, looking down at the remaining bean paste blocks, wondering what she was going to serve for dinner. She heard footsteps and looked up. Her daughter Bongyeom was back from school, carrying her book bag.

‘Why have you brought your book bag?’

‘It’s a half day. Oh, you’ve taken out the bean paste blocks.’ Bongyeom beamed as she picked up one of the blocks and inhaled its aroma.

‘Did you see your father on the way home?’

‘Yes. Fang Tong is here.’

‘Fang Tong? You’re sure?’ She let out a sigh of relief, only now realizing how nervous she had been all morning. ‘Where did you see your father?’

‘Fang Tong’s house. He was sitting with the militia. I don’t know what they were doing.’

The tension spreading to the woman from Bongyeom’s sudden frown! ‘Was Fang Tong with them?’

Bongyeom nodded. Then, she smiled. She took out shallots from her book bag. ‘So many shallots growing behind our school!’

‘Enough for a whole meal.’ The woman fondled them in approval before choosing one of the bigger ones, twisting off its stem, peeling it, and eating it. Bongyeom also popped one in her mouth.

‘Mother, if only I had some exercise shoes …’

The words had escaped her by accident, and Bongyeom fearfully looked away from her mother to the shallots on her lap. She could almost see, between the shallots, the lovely exercise shoes that her classmate Yong-ae wore as she ran as light as a sparrow.

‘You crazy child and your wants!’ The woman rubbed her nose and glared at her sideways.

Bongyeom felt the weight of the shallots turn into that of new exercise shoes. She mumbled, ‘Mother, every single want to you is crazy.’

The woman turned to her. ‘What else can your wants be? When we can barely afford to educate you, and you’re going on about exercise shoes! Look, child, it’s only thanks to the Enlightenment that you’re getting an education at all. When we were growing up, where would we have gone to learn? We had to fetch the water, weave hessian, tend the fields, and the only thing we could wish for was a pretty pair of straw sandals … Your father and mother are breaking their backs on the fields, but you’re going on about exercise shoes! Be glad you’re not starving. If you want to go on about your crazy wants, don’t go to school!’

‘You’re not the one sending me to school.’ Bongyeom felt slightly scared by her own rebellion, but she persisted.

The woman’s face turned red with fury. ‘Fine, even if it were your father sending you to school, I would’ve told you to quit. What kind of a daughter are you? Talking back just because she has some learning in her head instead of being silent when she’s spoken to! Yapping away with her jaw hanging loose! Fine, we have no money … If we had the money to buy you those silly shoes, we would’ve given Bongshik more schooling.’

Bongyeom could barely keep down the raw shallots she had been eating without any rice or water. Her eyes filled with tears. ‘Why don’t we have any money? Why can’t we send Big Brother to school?’

Then Bongyeom remembered something that her teacher had talked to her about, and she realized it was not her mother who was at fault for their poverty. But she could not help resenting her mother whose first instinct was always to castigate her daughter.

‘How do I know why we don’t have money! Why were you born to beggars instead of rich parents! You useless child, I’d be better off without you.’