12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

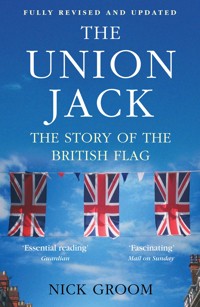

Known the world over as a symbol of the United Kingdom, the Union Jack is an intricate construction based on the crosses of St George, St Andrew and St Patrick. Nick Groom traces its long and fascinating past, from the development of the Royal Standard and seventeenth-century clashes over the precise balance of the English and Scottish elements of the first Union Jack to the modern controversies over the flag as a symbol of empire and its exploitation by ultra-rightwing political groups. The Union Jack is the first history of the icon used by everyone from the royalty to the military, pop stars and celebrities.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

THE UNION JACK

NICK GROOM is Professor in English at the University of Exeter. He writes widely on literature, music, contemporary art, and culture for both academic and popular publications, and is the author or editor of over a dozen books, including Shakespeare: A Graphic Guide (2010), The Gothic: A Very Short Introduction (2012), and The Seasons: A Celebration of the English Year (2014) – the last of which was shortlisted for the Katharine Briggs Folklore Prize and runner-up for BBC Countryfile Book of the Year. He lives on Dartmoor.

‘Humour and flashes of historical oddity make the book immensely readable… Groom explores this history with an unfailing inquisitiveness… Essential reading.’Mike Philips, Guardian

‘A wonderfully exuberant book… marvellously rich… Groom’s scope is formidable and this, together with the acuity of his judgements and the brio of his deployment of a vast wealth of resources, makes the work a model of cultural history for our time.’Hugh Lawson-Tancred, The Liberal

ALSO BY NICK GROOM

The Seasons

The Gothic

The Forger’s Shadow

Introducing Shakespeare

The Making of Percy’s Reliques

THE

UNIONJACK

The Story of the British Flag

NICK GROOM

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2006by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

First published in paperback in Great Britain in 2007 by Atlantic Books.

This revised and updated paperback edition first published inGreat Britain in 2017 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Nick Groom 2006, 2017

The moral right of Nick Groom to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The author and publisher wish to thank the following for permission to quote from copyrighted material: lines from ‘We are the Lion and the Unicorn’ reproduced by permission of PFD on behalf of the Estate of Laurie Lee; ‘Real Great Britain’ by Asian Dub Foundation reproduced by permission of C-Sonic of Asian Dub Foundation.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 78649 148 0

E-book ISBN 978 0 85789 931 6

Text design by Lindsay Nash

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

This book is dedicated to my grandfather, Pa,who served under the flag, and to all thosewho served with him.

The flag that’s braved a thousand yearsThe battle and the breeze.(Traditional)

CONTENTS

Illustrations

Author’s Note

Note to the New Edition

Preface

Glossary

I

Here Be Dragons

II

Where is St George?

III

The Old Enemies

IV

1606 and All That

V

See Albion’s Banners Join…

VI

An Englishman, an Irishman, and a Scotsman

VII

Two World Wars and One World Cup

VIII

Conclusion (2006 edition)

Afterword to the New Edition, 2006–17

Appendices

Early Texts of ‘Rule, Britannia’ and ‘God Save the King’

Chronology of English, Scottish, and British Monarchs

Dimensions of the Union Jack

Plain English Guide to Flying Flags

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Further Acknowledgements

Index

ILLUSTRATIONS

1. ‘A Young Daughter of the Picts’. Yale Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, USA / The Bridgeman Art Library.

2. Heraldic tattoo borne by British soldier. Roger-Viollet / Rex Features.

3. The Papal banner (Bayeux Tapestry). Mary Evans Picture Library.

4. The dragon standard of the Saxons (Bayeux Tapestry). Mary Evans Picture Library.

5. Tomb plaque of Geoffrey Plantagenet. Musee de Tesse, Le Mans, France / Lauros / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library.

6. Richard I. The British Library.

7. St George arming Edward III. The Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford (MS 92, fo.3r).

8. Christ leading a Crusade. The British Library.

9. The Wilton Diptych. The National Gallery, London.

10. The armorial bearings and badges of Henry VI, Richard III, Henry VII, and Edward IV. College of Arms MS. Vincent 152, p.53, and College of Arms MS. Vincent 152, p.54.

11. The Earl of Nottingham’s designs for the first Union Flag. The Trustees of the National Library of Scotland.

12. The Grand Union Flag. Private Collection / Archives Charmet / The Bridgeman Art Library.

13. Funeral escutcheon of Oliver Cromwell. Museum of London, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library.

14. ‘The Death of General Wolfe’. National Library of Canada, transfer from the Canadian War Memorials, 1921 (Gift of the 2nd Duke of Westminster, Eaton Hall, Cheshire, 1918).

15. Frontispiece to Edward Pettit, The Visions of the Reformation: or, A Discovery of the Follies and Villanies that have been Practis’d in Popish and Fanatical Thorough Reformations, since the Reformation of the Church of England (1683). Author’s collection.

16. ‘The Mary Rose’. Pepys Library, Magdalene College, Cambridge.

17. ‘The Fighting Temeraire’. The National Gallery, London.

18. ‘Britain’s Day’ poster. Swim Ink / Corbis.

19. Postcard treating the Union Jack as the flag of British Empire. Rykoff Collection / Corbis.

20. Poster for the British Empire Exhibition. Thames & Hudson Ltd. From The English World: History, Character and People, ed. Robert Blake, Thames & Hudson Ltd, London.

21. Africans shake hands. Hulton-Deutsch Collection / Corbis.

22. Sewing for victory. Hulton-Deutsch Collection / Corbis.

23. Women working on the layout of coronation banners. Bettmann / Corbis.

24. The Jam. London Features International.

25. Sebastian Coe. Sipa Press / Rex Features.

26. Ginger Spice at the Brit Awards. Richard Young / Rex Features.

27. Buckingham Palace provides the screen for a gigantic illuminated Union Jack. Tim Graham / Corbis.

28. The Black Watch on Operation Bracken, southern Iraq. Giles Penfound / Handout / Reuters / Corbis.

29. Navy divers at the Royal Oak. Rex Features.

30. Hoisting the Union Jack on the Houses of Parliament, c. 1902. The Print Collector / Getty Images.

31. Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II. John MacDougall / AFP / Getty Images.

32. Rihanna live. Shirlaine Forrest / WireImage / Getty Images.

33. Cuban fashion. Sarah Morgan / Getty Images.

34. Flags of the Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories. Brian Anthony / Alamy Stock Photo.

35. Irish Guards’ St Patrick’s Day shamrocks. Mark Cuthbert / UK Press / Getty Images.

36. England’s 2016 Grand Slam victory. Shaun Botterill / Getty Images.

37. Major Tim Peake in space. ESA / Getty Images.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the ‘Union Jack’ as ‘Originally and properly, a small British union flag flown as the jack of a ship; in later and more general use extended to any size or adaptation of the union flag (even when not used as a jack), and regarded as the national ensign’. Many people object to the term Union Jack being applied to the national ensign, arguing that the distinction between Union Jack and Union Flag should be observed because of the specific use of the Jack flag at sea: it is more accurate to say that it is the flag flown from the jackstaff of a ship. In the late nineteenth century there was an attempt to restrict the use of the term ‘Union Jack’ to such flags flown from the jackstaff of British maritime vessels.

The Union Flag has, however, been known as the Union Jack since the seventeenth century. An Admiralty Circular of 1902 noted that the two names were interchangeable, and Parliament confirmed the terminology by declaring in 1908 that ‘the Union Jack should be regarded as the national flag’. It is therefore unnecessarily pedantic to insist on calling the national ensign the ‘Union Flag’ unless one is distinguishing it from the ‘Union Jack’ flown by the Royal Navy, and this book follows the current everyday usage.

Likewise, for the sake of clarity, names are given in their most familiar form: hence ‘Glendower’ for ‘Glyndwr’, ‘Godwinson’ for ‘God-wineson’ or ‘Godwinsson’, ‘Stuart’ for ‘Stewart’, and so forth, and Old English forms have been modernized. A glossary of specialist terms can be found after the ‘Preface’ and a chronology of the English, Scottish, and British monarchs is printed at the back of the book.

NOTE TO THE NEW EDITION

In rereading this book for a new edition I have been struck by how much the Preface and Conclusion, written a dozen years ago, are of their time. In 2005, when the book was completed, Tony Blair won his third consecutive general election and assumed Presidency of the Council of the European Union, George W. Bush met with Vladimir Putin in Red Square to celebrate the sixtieth anniversary of Victory in Europe, and London was awarded the Olympic Games and within hours was attacked by the 7/7 suicide bombers. A referendum on Scottish independence, the UK leaving the EU, and radical right-wing populism were at the very fringe of serious politics – indeed, some would have said they constituted the lunatic fringe. Yet now these are the central issues of our time, dominating domestic and international affairs, and threatening to do so for years to come.

In preparing this new edition I have, however, resisted the temptation to rewrite the original Preface and Conclusion with the benefit of hindsight, as these opinion pieces give a glimpse of the mood in 2006, and I am therefore grateful to my publisher for affording me the opportunity to write a new Afterword to reflect on the fortunes of the flag since the book was first published. I have also, of course, taken the opportunity to make minor adjustments to the text here and there to improve tone, style, and clarity, as well as correcting a number of minor errors that have been brought to my attention.

PREFACE

THE UNION JACK is instantly and universally recognizable: it flies proudly from government buildings, is waved gaily at the Last Night of the Proms, and is draped enthusiastically over the shoulders of victorious British athletes. It is also cheerfully quoted in dozens of contexts – anything from James Bond films to advertisements for cheese, from novelty boxer shorts to punk fashion – and remains synonymous with Great Britain and the ‘Empire on which the sun never set’. But what has the Union Jack really stood for in the past, and what – if anything – does it symbolize today?

Everyone in the British Isles and the former British Empire has their own relationship with the flag – as do many more people throughout the world – and the following account is only one of thousands that could be told. In one sense, the story can be summarized in a single sentence: the Union Jack is made up of the crosses of St George, St Andrew, and St Patrick, respectively the patron saints of England, Scotland, and Ireland, and it was first flown on 1 January 1801, when the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland came into being. And yet a long and turbulent history leads to that moment: for almost two centuries there had already been a flag symbolizing the union between Scotland and England (and its principality Wales), and, even before that first Union Flag was raised in 1606, there are over a thousand years of Union Jack prehistory – a strange menagerie of dragons, lions, and ravens. These were the standards of the Dark Ages: of the armies that fought across the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex, who rallied against the persistent raids of Viking marauders, and who at last fell at the Battle of Hastings to the Norman invaders. Such standards developed into the badges of medieval heraldry – that cryptic science that happily places an armed blue lion ramping in a field of gold against a shower of red hearts – and the laws of heraldry helped to establish both the elements that make up the Union Jack and the ways in which they were put together.

So the Union Jack was conceived on the banners of the ancient Britons and in heraldry, and its birth came under the influence of the cults of certain saints. It was carried across the globe as the ensign of the British Empire, and was a symbol of everything that went with it. Centuries later, the Union Jack has arrived in the present day, where, in addition to leading a tireless life within popular culture, it remains very much alive as a potent political symbol. Indeed, because it is explicitly a flag of union, the Union Jack is a perpetual reminder of the unity – and disunity – between the nations of Britain, and of the persistent problems of compromise in defining a British identity.

The Union Jack is, then, the flag of Britain – but where is Britain? Or, one might ask, what is Britain? In his essay ‘The Lion and the Unicorn’, George Orwell apologizes for confusing terms such as ‘the nation’, ‘England’, and ‘Britain’. He notes that the islands have at least six different names: England, Britain, Great Britain, the British Isles, the United Kingdom, ‘and, in very exalted moments, Albion’.1 Great Britain is actually formed of the kingdoms of England and Scotland and the principality of Wales; the United Kingdom is currently the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the British Isles still includes the Republic of Ireland and the Crown Dependencies (the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands). Orwell’s aim was to play down the differences and promote a sense of unity during the Second World War (the essay was published on 19 February 1941), but today these differences are being played up.

Recently, there have been suggestions made by such august bodies as the British Council that the term ‘British Isles’ should be abandoned and replaced with something like ‘the North-East Atlantic Archi pelago’.2 This is a ghastly phrase, but it would at least remove the confusion that exists, among the English at least, between England, Britain, and the UK – even in George Orwell’s mind. There are serious political implications in confusing the words Britain and England. Making England, a part of the Union, stand for the whole of Great Britain has the potential to be profoundly insulting as it treats Scotland and Wales as if they are minor English provinces, and it has been symptomatic of the history of this group of North European islands that England has been almost perpetually seeking to usurp the title of Britain for itself, if sometimes with the collusion of its partners. So implicit is the imagined identity between England and Britain that many English people cannot perceive that the two words mean entirely different things, and describe significantly different landmasses with their own distinct histories. The confusion persists in Europe and beyond. I was talking to a German recently who was taken aback to learn that the Scots had their own football team: she assumed that ‘Eng-er-land’ were cheered on by the whole of the British Isles – not least because English football supporters often carried the Union Jack.

But a phrase such as ‘the North-East Atlantic Archipelago’ is worrying in that it effaces the past. In contrast, names such as ‘Great Britain’ and ‘British Isles’ embrace history, attempting to make sense of two thousand years of enmity and amity; they are not just handy geographical descriptions, but testaments to relationships and shared histories, struggles, and conflicts. The history of Great Britain is therefore a grand narrative – an attempt to weave many narratives into one national epic – and the very words ‘Great Britain’ are a shorthand way of describing this vast story. And retrospectively, looking back from the first decade of the twenty-first century, this history appears to make sense: the fact that Great Britain has mutated and survived – even evolved – imposes a pattern of apparent inevitability and manifest destiny on the chaos of historical process that has brought us to this point. It is in the nature of countries to do so. They present themselves as if they are permanent and eternal, as essential entities rather than political formations. But as the historian John Cannon has remarked in describing the formation and history of England, ‘There was no predestined goal, no manifest destiny, save perhaps towards a kingdom of the British Isles, which was never quite achieved.’3

In the case of Great Britain, this essence is one of unity – unity and disunity are the defining themes of Britain’s epic history. The dream of union has been long and for many it has been a nightmare, but it is the one dream from which Britain can never awake: to do so would be to end the ‘British Isles’ as a meaningful concept. Now, after two millennia in which the kingdoms dreamt of union and then strove to extend that vision of unity worldwide, the past century has seen the Union in decline: the dismantling of the British Empire, the independence of the Republic of Ireland, and more recently in 1999, the limited devolution of Scotland and Wales in the founding of the Scottish Parliament and the Welsh National Assembly. Was the Union, which arguably only lasted from 1746 to 1922, an historical anomaly? Certainly the pattern is now changing and among the ramifications of this gradual breakdown is an ensuing crisis of British identity, and, simultaneously, of English identity, which has long relied on England’s primacy within Great Britain to provide its foundations.

The idea of union is, then, at the heart of this book: the union of England with Wales, Scotland, and Ireland to form a United Kingdom. The ebb and flow of the dream of union washes around the British shores like the seas that surround it, confirming to its inhabitants the islands’ independence from mainland European geography and history, and the Union Jack, made by laying together the crosses of the realm’s national patron saints, is its symbol: the history of the Union and its extension across the globe forms the back-story to the biography of the flag. Some may find all this, in Raphael Samuel’s words, to be ‘drum-and-trumpet history’.4 That is unavoidable, as the flag has spent much of its life in the company of drums and trumpets.

Like the United Kingdom, then, the Union Jack is the result of two thousand years of unionist ambitions. Like the United Kingdom again, the Union Jack is an invention, assembled from different parts that have been subtly altered in order to retain their identity as part of a larger whole. The flag is a carefully balanced compromise, both a map and a history: a perpetual reminder and emblem of unification. Consequently, as the relationship between the four nations within the British Union shifts, the very concept of Britain itself is being rethought. Where does this leave the flag? On 12 April 2006, it was four hundred years since a flag of the Union had first been raised. Is it finally time to lower the old standard for good, or will the Union Jack stream across new skies, riding on the winds of change as the sign that leads Great Britain ever onward through the twenty-first century?

GLOSSARY

Achievement

the complete armorial bearings, consisting of shield (or coat) of arms, crest, supporters, badges, motto, insignia, and so forth

Argent

(heraldic metal) silver or white

Azure

(heraldic tincture) blue

Blazon

originally a verbal account of a knight’s arms, delivered at a tournament by a herald; now means the written description of a coat of arms

Canton

the upper, left-hand quarter of a shield or flag; the most prestigious position

Counter-change

reversing two colours

Dexter

the right-hand side of a shield or flag, from the position of the bearer (i.e. the left side as viewed)

Dip

the depth of a flag

Ensign

the adaptation of a national flag for use at sea, flown at the stern of a vessel

Field

the background colour of a design

Fimbriation

narrow white border to distinguish between two colours laid together

Fly

the furthest edge of a flag from the staff

Gules

(heraldic tincture) red

Halyard

rope used for raising or lowering flag up a staff

Hoist

the closest edge of a flag to the staff

Impalement

a form of marshalling: two coats of arms presented side-by-side

Length

the measurement of a flag from hoist to fly

Marshalling

combining coats of arms, for example through marriage

Or

(heraldic metal) gold or yellow

Purpure

(heraldic tincture) purple

Quartering

a form of marshalling: dividing shield or flag into four and alternating different sets of coats of arms

Rampant

an animal represented as standing on its hind-legs, with fore-legs raised

Sable

(heraldic tincture) black

Saltire

a diagonal cross

Sinister

the left-hand side of a shield or flag, from the position of the bearer (i.e. the right side as viewed)

Truck

a runner for a halyard

Vert

(heraldic tincture) green

Vexillology

the study of flags

I HERE BE DRAGONS

Edwin, King of Northumberland, had alwayes one Ensign carried before him called in English a Tuffe…King Oswald had a Bannerol of Gold and Purple…Cuthred, King of Wessex, bare in his Banner a golden Dragon at the battel of Bureford…and the Danes in their Standard a Raven.

William Camden, Remains (1674), 228

FLAGS ARE AMONG the most ancient of deliberate human signs. Since Biblical times, they have served to identify persons and families of rank, as well as provinces, regions, and peoples. They began as rallying points – emblems or images around which allies could gather on the battle field or at times of crisis – and so were from the beginning essentially signs of union and identity as well as being statements of distinction and exception. Flags have, as we shall see, always been valued as important objects in themselves, and even been reputed to possess supernatural powers. They have, in different ways, also symbolized the union of Great Britain. Before the Union Jack flag, the idea of a British union was not only expressed in medieval heraldry, but also in the millennium before that in the banners of the Dark Ages. So it is worth tracing the vagaries of the heraldic and the pre-heraldic imagination, as these attempts to represent both visually and symbolically a union of Great Britain are effectively prototypes of the Union Jack. The perspective offered here is therefore necessarily long: Britons have been striking flags and raising standards for some two thousand years; before then, they found other ways of declaring their allegiances and loyalties.

The first references to the earliest inhabitants of the British Isles suggest that, initially at least, the ancient Britons were not known for their flags, banners, or standards. Instead, they bore a more personal, literal form of insignia. The ancient Britons wore their identifying emblems on the body itself, and this communal fashion characterized them across the ancient world. Indeed, these people appear to have named themselves after their body art. ‘Britons’ literally means ‘people of the designs’, and is derived from the Celtic ‘Priteni’.* In 320 BC, the ancient explorer Pytheas first circumnavigated the ‘Pritannic Isles’; the Greeks adapted the word to ‘Pretanoi’, and later the Romans to the Latin ‘Britanni’. Some of these Britons painted themselves: ‘Picts’ literally means ‘the painted people’ and in The Gallic Wars Caesar remarks that ‘All the Britains, indeed, dye themselves with woad, which occasions a bluish colour, and thereby have a more terrible appearance in fight.’1 Tattooing also seems to have been widespread and customary. William of Malmesbury noted that the ancient Britons pricked patterns into their skin, and the pioneering sixteenth-century antiquary William Camden argued that the Picts and Britons were ‘painted peoples’ who stained and coloured their bodies and moreover were characterized by ‘their cutting, pinking, and pouncing of their flesh’.2 He even proposed the ancient Britons as the originators of heraldry:

some give the first honour of the invention of the Armouries [insignia] in this part of the World to the ancient Picts and Britains, who going naked to the wars, adorned their bodies with figures and blazons of divers colours, which they conjecture to have been several for particular Families, as they fought divided by kindreds.3

These figures were characteristically, if fancifully, depicted in John Speed’s The History of Great Britaine under the Conquests of the Romans, Saxons, Danes and Norwegians (1611), naked but decorated with head-to-toe depictions of the sun and moon, stars and flowers.4

The Brits are currently the most tattooed people in Europe, so perhaps little has changed. But despite this – and the ancient origins of British body art – tattooing is still often frowned upon, particularly as an expression of national identity. As such, it retains some of its earliest stigma – the word is ancient Greek for ‘mark’ – and ancient British tattoos were called ‘Britonum stigmata’.5 Like branding, tattooing was a literal stigma: a mark of disgrace or ownership, as well as being associated with barbarians such as the Scythians and Britons. For these reasons, the Greeks and Romans identified criminals and slaves by tattooing them, which was a supremely legible way of both proclaiming a crime and indicating the successful execution and enforcement of the law. It also meant that the lack of such marks on the body was itself a form of marking, as it was effectively a way of recognizing civilized and law-abiding citizens. But stigmatizing of this sort generated dissident confederacies, and tattoos became ways in which individuals could declare shared transgressions and identify themselves as members of outlawed subcultures. Tattoos were, for example, popular among the early Christians as ways of bearing witness to their prosecution under the Romans. Tattoos not only permanently recorded a statement of faith and mortified the flesh, they could also be interpreted as an imitation of the stigmata of crucifixion, and it is not impossible that St Paul was tattooed with the five wounds of Christ (‘I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus’).6 Christian tattooing remained popular throughout the Middle Ages, and pilgrims were still receiving tattoos to record their visits to shrines in Bethlehem and Jerusalem well into the seventeenth century; at the same time, comparable forms of body marking such as branding and ear-paring were firmly established as sentences in English criminal law.

So when the Romans arrived with their invasion force on the shores of Britain in AD 43, they were faced with tattooed, woad-painted Britons.7 The armies of the emperor Claudius, in contrast, bristled with ensigns: most notably the iron eagle carried before the legions that bore the legend SPQR (Senatus Populusque Romanus: ‘The Senate and the People of Rome’). These imperial insignia were typical organizational devices of the seasoned, well-drilled Roman military that made them an all but irresistible force when on campaign, but it is noticeable that later invaders of the British Isles, as well as migrants, took up the idea and bore similar standards: the Danes carried one of the ‘beasts of battle’, a raven (sometimes actually a live bird chained to a tall staff or mounted in a cage), and the Jutes traditionally rallied to the sign of the white horse. Standards were also soon adopted by the ancient Britons too, but neither eagle, raven, nor horse captured the British imagination in quite the same way as did one particular Roman ensign: the dragon. It would fly across the country for the next thousand years and was the first emblem of a united England, if not a united Britain. In a very real sense, the Union Jack flag evolved out of the sign of the winged serpent.

The use of dragons as military ensigns originated in the East among the Parthians and the Dacians, from where the practice was adopted by the Roman army. A draco designated a cohort of soldiers (300–600 men), ten cohorts making one legion. The flying dragon became the cohort’s standard, and its standard-bearer was a draconarius; it was one of six different Roman military insignia.* Some twenty dragon standards appear on Trajan’s Column in Rome (AD 106) and later on the Arch of Galerius (AD 311). St Isidore of Seville wrote in his encyclopaedic seventh-century treatise Etymologies, or Origins that the sign of the dragon was borne to battle in remembrance of Apollo slaying Python, a fearsome serpent.8

But they were more than just signs: Roman dragons were elaborate constructions. The Greek historian Flavius Arrianus (Arrian), a crony of the emperor Hadrian, wrote in the mid-second century AD that dracontine standards were originally Scythian and ‘made by sewing scraps of dyed cloth together’:

from head to tail they look like serpents…And when the horses are spurred on the wind fills them and they swell out so that they look remarkably like beasts and even hiss in the breeze which the sudden movement sends through them.9

They must have looked terrifyingly spectacular. The fourth-century historian Ammianus Marcellinus described in his Histories the entry of Constantius into Rome in AD 357 surrounded by dragons [‘dracones’]:

he was surrounded by dragons, woven out of purple thread and bound to the golden and jewelled tops of spears, with wide mouths open to the breeze and hence hissing as if roused by anger, and leaving their tails winding in the wind.10

In other words, these standards were not flags but war machines that roared in the wind and writhed above the invading army like malevolent guardians – instruments akin to bagpipes or the sirens attached to aerial dive-bombers: they deployed noise as a weapon.

Although the dragon was clearly identified with Rome from the second century AD, it was later used by the Byzantines, Carolingians, Vandals, Langobards, and Saxons, and Viking longships were famously dragon-prowed. It also became a favourite image among the original ancient Britons and the Romano-Britons, a diverse people popularly and sentimentally known since the eighteenth century as the Celts.11 After the Romans finally withdrew in AD 408, Britain began to be settled by the Teutonic tribes – in particular the Saxons from Holstein, and the Angles from the Angeln region, who named their territory Anglia. The process of Anglo-Saxon settlement and the long Celtic withdrawal to Wales, Cornwall, Ireland, and Brittany (‘Little Britain’, as opposed to ‘Great Britain’, the largest of the British Isles) was gradual and generally peaceful. But as the ancient and R0mano-Britons were driven further west, they did eventually unite under the dragon standard for a series of battles. It is possibly from these that the legend of King Arthur originated. Arthur was the focus of an invented, imagined unity in early chronicles and histories: the Matter of Britain was effectively a matter of union.

Arthur became intimately associated with the dragon standard. The military emblem of his father, Uther Pendragon, was allegedly a gold dragon which he used ‘to carry about with him in the wars’.12 Medieval heralds claimed that Uther’s arms had been two green dragons, back-to-back and therefore presumably rampant (rearing up on back legs), and his succession had purportedly been predicted by a ball of fire shaped like a dragon.13 Uther’s son Arthur was often likewise depicted in a dragon-crested helmet: dragonish. But such details were all derived from legends circulating in the Middle Ages, centuries later than the Arthurian epoch, and they do not square with the scant historical evidence for King Arthur.

He is first mentioned in the Historia Brittonum, attributed to Nennius and written in the eighth or early ninth century. Arthur is fighting at Guinnion Fort:

Arthur carried the image of the holy Mary, the everlasting virgin, on his shield, and the heathen were put to flight on that day and there was a great slaughter made on them through the power of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the power of the holy Virgin Mary his mother…14

The Annals of Wales for the year AD 516 also possibly refers to the emblem Arthur carried on his shield: ‘The battle of Badon, in which Arthur carried the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ for three days and nights on his shoulders and the Britons were the victors.’15 In other words, the earliest references to Arthur depict him as a champion of the Virgin Mary and bearer of the cross, rather than as marching beneath the howling dragon. But by the twelfth century, Geoffrey of Monmouth pictured the mythical king crowned with the familiar dragon crest, if carrying an image of the Virgin on his shield.16 Geoffrey subsequently describes Arthur’s battle against Lucius Hiberius, where ‘he set up the Golden Dragon which he had as his personal standard’.17

The dragon may have been developing as a secular symbol of unity between the British people, yet it was also a symbol of the pagan and the diabolical, and the Christian Church had a growing antipathy towards its domestic and military uses. One of the Beasts of Apocalypse described in the Revelation of St John the Divine was like a dragon, and – significantly – able to summon fire: ‘And I beheld another beast coming up out of the earth…and he spake as a dragon…And he doeth great wonders, so that he maketh fire come down from heaven on the earth in the sight of men.’18

Popular references to fire-breathing dragons did not appear until about AD 500, possibly associated with the invention of the incendiary weapon Greek fire. But although fire had elemental associations with aerial creatures, it was also, of course, the essence of Hell, and so from the late fourth century Christians were encouraged to reject all that was dragonish.19 The Christian writer Prudentius explicitly outlawed the dracontine standard. He described in his Peristephanon how good Christians had abandoned Caesar’s ensigns for the sign of the cross, and ‘in place of the swelling draperies of the serpents which they used to carry, led the way with the glorious wood which subdued the serpent’.20

This victory of the wooden cross over the fiery dragon is, as we shall see in the next chapter, repeated in many miracles in which serpents are quelled by saints making the sign of the cross. It is symbolic of the victory of the Church over the Devil, over paganism, over evil, and there are more than forty dragon-slaying saints in the Western Church.21 But although the actual appearance of dragons was considered to be a dire omen and a sighting over Northumbria in 793 was believed to presage famine, the creature continued to be powerfully associated with a unified Britain.22 Alongside the growing Arthurian associations, the dragon was the symbol of Cadwallader, the last king of the ancient Britons and (it was later claimed) the ancestor of Henry VII. The golden dragon also became the royal symbol of the West Saxon army; in 752, Cuthred, King of Wessex, marched to victory against the Mercians at Burford under the emblem.23

How unified was the country at this time? Sceptics of these early unionist claims should bear in mind that in his Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, 731), the Venerable Bede had already identified England both as a single nation, and as the nation that dominated Great Britain. Bede described ‘Engla-land’ – gens Anglorum – as a region of five languages and four peoples: the English, the British or Brittones (the original inhabitants), the Irish who had settled in Argyll and the Western Isles, known as the Scotti, and the Picts. The subsequent Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (based on Bede) records the information as follows:

The island of Britain is eight hundred miles long and two hundred miles broad; and here in this island are five languages: English and British and Welsh and Scottish and Pictish and Book-language.* The first inhabitants of this land were Britons, who came from Armorica [Brittany], and settled at first in the southern part of Britain. Then it happened that Picts came from the south, Scythia [north-east Black Sea], with long-ships (not many) and landed at first in northern Ireland, and there asked the Scots if they might live there. But they would not let them, because they said that they could not all live there together. And then the Scots said: ‘We can, however, give you good advice. We know another island to the east from here where you can live if you wish, and if anyone resists you, we will help you so that you can conquer it.’ Then the Picts went and took possession of the northern part of this land; and the Britons had the southern part…24

The English themselves were an amalgamation of, among others, Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, as well as remaining the earlier inhabitants – Britons and Romano-Britons – and they occupied the seven kingdoms, or ‘Heptarchy’ – Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Kent, Essex, Sussex, and Wessex – not to mention the petty ‘Celtic’ kingdoms of Scotland, Wales, and Cornwall.† Although these kingdoms were not politically or economically united, there was nevertheless a concept – an aim, even – of the bretwalda or overlord of the English kings.25 Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum was in one sense, then, a manifesto for union. He inspired subsequent rulers to attempt to unite England beyond the sevenfold diversity of the Heptarchy and to secure allegiance from their immediate British neighbours. In the course of this, Bede proposed that the unity of the Church and Christianity had been and would be instrumental in identifying and unifying the English nation. And coincidentally, in Bede’s account of the unifying influence of the Church of Rome comes another early reference to flags on British soil. At St Augustine’s audience with King Æthelberht in 597, Augustine carried a vexillum: ‘bearing as their standard a silver cross and the image of our Lord and Saviour painted on a panel’.26 A vexillum could refer to a portable shrine or reliquary, but the word also meant ‘banner’ – in particular a square flag hung from a crossbar – hence vexillology, the study of flags. The two meanings are probably connected: it is possible that flags developed in Europe at this time from the supernatural properties attributed to reliquary wrappings. Reliquaries – sacred containers in which holy relics were housed – became divine by their association with the relics they protected, and so Augustine’s banner may have been either an actual reliquary covered in cloth or just the cloth cover itself. In the seventh century, for example, the remains of King Oswald had been entombed and a vexillum of purple and gold placed over the sarcophagus; this fabric wrapping could clearly have been carried into battle as a standard. The tradition is, in a sense, continued by honouring those who have died on active service by draping their coffins in the national flag.

Augustine’s standards, the silver cross and the image of Christ, may not have been adopted as the emblem of one England under one Church, but the Church did contribute to the unity of the country over the next 150 years, and it was the Viking chieftain Offa who was to be proclaimed variously rex Anglorum (King of the English) and rex totius Anglorum patriae (King of all England). In 757, Offa became King of the Mercians and thereafter subjugated the surrounding regions, invading Kent, Essex, and London, and by 774 achieving some sort of supremacy. Although the titles rex Anglorum and rex totius Anglorum patriae were retrospectively applied and during his lifetime Offa was only ever rex Merciorum (King of Mercia), it is nevertheless from about this time – over a century before Alfred the Great was crowned – that a more stable idea of England emerged. Relations with the Britons, Vikings, French, Scots, Welsh, and Irish began to settle, and Offa did succeed, for instance, in imposing a common coinage on his territories. Henceforth, the nation gradually crystallized as laws, borders, currency, religion, and trade became standardized, and as political and military forces were consolidated against common enemies such as, ironically, the Danes.

Offa’s ambitions were in part inspired by Bede – whom he had read. The germ of the idea of union began to work across south-east England, and eventually became enshrined in the ideology of the English monarchy and in the body of the English king. The strength of this idea, that the monarch was intimately related to the nation, was firmly established by 1016 when Canute the Great, another Dane, succeeded.27This proved no threat to English identity: it was the institution of the monarchy rather than the nationality of the monarch that was necessary in maintaining national identity and unity, and this has since been a powerful feature of the English and later the British throne. The Norman invasion of 1066 did not really threaten the notion of a unified England. Although William the Conqueror remained heavily involved in French affairs, this created an opportunity for later English kings to develop interests in Normandy, Anjou, Aquitaine, and other provinces and principalities in France as extensions of Englishness and the English union. More recently, the accession of a Dutchman in 1689 and a German in 1714 presented no discernible threat to English or British identity either; neither did the rise of the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (although they did prudently change their name to Windsor during the Great War), nor does the fact that the current heir to the throne is half-Greek.28

Offa’s overlordship was not, however, sustained by his immediate successors. Within thirty years Wessex had become the leading English power and Ecgberht, King of the West Saxons from 802, became overlord of the English kings. Although his tenure was very brief (828–9), it is nevertheless from Ecgberht that the British royal family can trace its descent, for in 886, halfway through his own reign, Ecgberht’s grandson Alfred became overlord of the English. This is the point that effectively marks the founding of a continuous English identity: Alfred the Great is popularly considered to have been the first ruler of all England, ‘the first Good King’, and even in his own time was described in 886 as the ruler of ‘all Angelcyn’ – the Anglo-Saxon name for what Bede had called in Latin gens Anglorum.29 He was the sovereign who cultivated the language, established the navy, and secured the country against the Danes – in the course of which in 878 he had symbolically seized one of the Danish raven standards at Cynwit (Countisbury). The cult of Alfred and the belief in a unified England went hand-in-hand from this point, and by the nineteenth century Alfred was considered to be both a model monarch and the archetypal Englishman, ‘England’s darling’.

Under the bretwalda, the union began to stabilize. By the time Alfred’s son Edward the Elder was on the throne, he was receiving personal submissions from all sorts of kings scattered across Britain in acknowledgement of his overlordship. In 918, Edward received such submissions from the Welsh kings of Gwynedd and Dyfed, and according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 924,

the king of Scots and all the nation of Scots chose him as father and lord; and so also did Rægnald and Eadwulf’s sons and all those who live in Northumbria, both English and Danish and Norwegians and others; and also the king of the Strathclyde Britons and all the Strathclyde Britons.30

Edward the Elder’s son Athelstan also took the title rex Anglorum, and moreover in 928 he was the first Wessex king to claim the whole of the country, styling himself on his charters and coins rex totius Britanniae (King of all Britain). In this, he was acknowledged by the northern kings, the five kings of Wales, and the last kings of Cornwall. Athelstan was also, interestingly, the first English monarch to have his likeness memorialized in a contemporary painting. The accession of Edgar the Peacemaker in 959 was similarly supported by eight kings, variously of Wales, Scotland, Cumbria, and Scandinavia, who supposedly rowed him up and down the River Dee. Reminiscent of Athelstan, the Peacemaker styled himself Albionis Imperator Augustus, and his coronation gave a sense that the whole of Britain could be united – if, as the chronicler Æthelweard rather tartly commented, it was under the English overlord: ‘Britain is now called England,’ he wrote, ‘thereby assuming the name of the victors.’31

Throughout this period the English fought under the dracontine standard, and therefore the dragon itself can be seen as a symbol of unity, raising a national awareness, particularly among the Saxons. Yet despite the Celtic enthusiasm for curling decorative dragonish motifs, there are surprisingly few early references to dragons in Welsh and Irish iconography: the Historia Brittonum notes only a fifth-century report of a sinister confrontation between a white dragon and a red dragon – a prediction that the Welsh red dragon would overcome the invading Saxons and expel them from Britain (an omen that has been a long time coming to pass). There are no reports of dragons in the sixth-century cycle of Welsh poems Y Gododdin, and it appears that the Welsh dragon ensign actually originated in the twelfth century. Likewise, dragons are absent from Ireland. The English, however, continued to raise dragons above their armies. A dragon flew at the Battle of Assandun in 1016 and perhaps most famously fifty years later, at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, where King Harold’s standards were the golden dragon of Wessex and the shining figure of a warrior.

1066 – the most memorable date in English history – witnessed a three-way struggle for the country fought between King Harold of England, King Harald Hardrada of Norway, and Duke William of Normandy (William the Bastard). Edward the Confessor had supposedly nominated William his successor, to which Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, allegedly acquiesced while in Normandy in 1064. But it was claimed that on his deathbed the Confessor had revoked this succession. Instead, he appointed his wife, Edith, to rule with her brother – her brother being Harold Godwinson. King Harold II was crowned in Westminster Abbey on 5 or 6 January 1066, whereupon William immediately began preparing an invasion force. But there was a third factor: Harold’s brother Tostig, the exiled Earl of Northumberland. He joined forces with the warrior-king Harald Hardrada (also known as Harald Sigurdsson) with his own plans to invade. The invasion season opened in the early autumn. Harald and Tostig took York on 20 September 1066 after the Battle of Gate Fulford, before being slain by Harold at Stamford Bridge on 25 September. Harold then marched his victorious army down to Hastings, where they met William’s force on 14 October and were famously defeated.

Flags feature prominently in the histories and legends of this epochal year. Harald Hardrada marched beneath his black banner Landeydan, or ‘Land-Waster’ – a magical flag that had hitherto guaranteed victory in each of his many battles.* It was, Harald declared, his most treasured possession; fittingly, after Stamford Bridge ‘Land-Waster’ was lost.32 In one story, however, it is reputed to have been recovered and preserved by the MacLeod clan in Dunvegan Castle on the Isle of Skye, with a promise that the fairies will come to the aid of the MacLeods whenever it is flown – although they will only do so three times. The fairy fl ag has already been raised twice, at the battles of Glendale (1490) and Trumpan (1580). It is now too delicate to be unfurled a third time, but soldiers of the MacLeod clan did take tiny squares of the fabric when they left to fight in the two world wars of the twentieth century.

William the Bastard had no fairy flag, but he did have God on his side. One of his earliest preparations for invasion had been to send a delegation to the Vatican. Pope Alexander II had replied by blessing the campaign with a Papal banner, giving the Normans the blessing of the Church in their invasion: it means that had Harold won, he would have been excommunicated (an early example of English resistance to Rome, perhaps). As it was, after their victory the Normans presented Harold’s standard of the golden warrior to the Pope in thanks, suggesting it was a representation of a soldier-saint rather than a figure from classical myth such as Ajax. Papal banners subsequently became popular talismans on the Crusades.

These flags are depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry, which in its commemoration of the invasion offers a fascinating glimpse of the insignia and regalia of the Saxon and Norman knights. The tapestry shows thirty-seven pennons (or pennants) on Norman lances, twenty-eight of which are triple-tailed, and one Saxon pennon even has four streamers.* From the devices carried on shields, it is apparent that these designs are all ‘pre-heraldic’, with no laws or conventions to govern them. The most elaborate pennon is that borne by Count Eustace II of Boulogne, which may have been the Papal banner secured by Duke William, whereas the most elaborate standard is the Saxon dragon (actually a wyvern, as it has only two legs). It is last seen languishing on the ground as Harold falls – since the time of Edmund Ironside, it had been conventional for the English king to position himself between his two standards.

The Battle of Hastings marked the end of the years of the dragon. Although for centuries English armies would continue to bear dragon standards into battle, and real dragons still occasionally made spectacular appearances over the English countryside – for instance, at Christchurch in Hampshire in 1113 – they had very little formal status. It was not until the advent of the Tudors in 1485 that dragons received any royal recognition of their symbolic heritage as the fabulous beasts of British union, but even then their tenancy was brief and marginal and in any case based on the later Welsh emblem; they have since been long neglected. But the draco of the Romans, the golden dragon of Wessex, and the wyvern of King Harold II were succeeded by an equally fierce – if non-native – creature. From now on, lions held court. They would be adopted, in various guises, by the English and Scottish kings, and by the princes of Wales.

William’s own personal standard at Hastings was a pair of lions – he supposedly carried one lion for Normandy and one for Maine, of which he had become count in 1063, and his successors likewise bore two lions. His son, Henry I – the ‘Lion of Justice’ – kept lions at his Woodstock menagerie (probably the first to be on British soil since those brought by the Romans), and he may also have been drawn to the emblem via his wife, Aelis of Louvain, whose seal bore a lion. Henry presented his son-in-law, Geoffrey of Anjou, with a shield bearing at least four golden lions, and they later appeared on the shield of William Longspee, Geoffrey’s grandson. This strongly suggests an heraldic inheritance – a significant innovation.33 Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry II’s wife, used a seal of three lions, and the Great Seal of Henry II’s son and heir Richard I Coeur de lion (Lionheart) showed a lion (or possibly two) rampant. This seal was lost while the Lionheart was in captivity, and when he returned in 1195 he adopted into his second Great Seal a standard of three golden lions passant regardant (crouching and watching) on a red field or background (he is depicted bearing a shield of these three lions in an illustration to the thirteenth-century Greater Chronicle of Matthew Paris).34 Although the Lionheart still took the dragon standard on Crusade, where it was borne by Peter des Preaux, the three lions became the armorial bearings for succeeding Plantagenet kings, and remain on the royal coat of arms to this day.35 They also form the basis of the team badge on England’s cricket sweaters and football jerseys.

King John is clearly shown on his Great Seal with three lions, as is Edward I.36 A contemporary illustration depicting the young Edward III on his accession shows him being armed by St George and bearing the three lions on his shield and surcoat (a loose garment worn over armour). Interestingly, heraldic lions are always presented individually and ‘rampant’, and a lion crouching or in the company of similar beasts is technically described as a ‘leopard’ – a distinction noted by the chronicler of the siege of Caerlaverock (written 1307–14), who described Edward I thus:

his banner were three leopards courant of fine gold, set on red, fierce, haughty, and cruel; thus placed to signify that, like them, the King is dreadful, fierce, and proud to his enemies, for his bite is slight to none who inflame his anger; not but his kindness is soon rekindled towards such as seek his friendship or submit to his power. Such a Prince was well suited to be the chieftain of noble personages.37

It was not until the seventeenth century that the English leopards were officially designated lions.

The Prince of Wales also bore lions on his shield, and the kings of Scotland had used the emblem of a lion for centuries: ‘the ruddy lion ramping in his field of tressured gold’ (a rearing red lion against a yellow background, surrounded by a tressure or ornate frame).38 According to Hector Boece (c. 1520), the ‘reid lioun, rampand in ane feild of gold’ image went back as far as 330 BC and was brought to Scotland from Ireland in the sixth century by Fergus Mor MacErc, who settled his people in Dalriada.39 It is first mentioned, however, at the Battle of the Standard in 1138, where the Scottish king, David the Saint of Scotland, bore a lion standard – the first reference to the flag being raised. Traditionally, however, the red lion was attributed to David’s grandson, William I, which subsequently earned him the sobriquet ‘the Lion’, and it survives on the Great Seal of his son, Alexander II. In this early rendering, the lion lacks its tressure and lilies, which were added later from Scotland’s association with France.40 St Aelred, however, claimed that in the twelfth century the royal standard of Scotland depicted – of all things – a dragon.41

With the lions were to come other national badges, many of which reflected the native flora of the Isles, as opposed to the fantastic fauna of the medieval imagination. For England, there was the broom plant of the royal Plantagenet dynasty (Henry II–Richard II), supposedly taken from Geoffrey of Anjou’s habit of wearing in his helmet a sprig of yellow broom (in French, Plante genet); for Scotland there was the crowned thistle; for Ireland, the shamrock or trefoil; and for Wales, the leek and occasionally the mistletoe. Edward I also adopted a gold rose, and his brother Edmund Crouchback, second son of Henry III and first Earl of Lancaster, took a red rose, as did his descendants – roses having been traditionally brought back from the Crusades by the Lion-heart. Edmund’s tomb was painted with red roses, and the symbolism poss ibly gained momentum from his mother Eleanor of Provence, who was likewise characterized by roses.42 In contrast, Edmund of Langley, Duke of York, adopted the white rose, and the emblems of the two houses would eventually of course christen their struggle for the throne the Wars of the Roses.43 As Richard of York declares in Shakespeare’s Henry VI (Part 3):

I cannot rest

Until the white rose that I wear be dy’d

Even in the lukewarm blood of Henry’s heart.

(I, ii, 32–4)

Eventually, in recognition of the marriage of the Lancastrian Henry Tudor to Elizabeth of York, the Tudors (Henry VII–Elizabeth I) took a variegated red and white rose as their badge, together with a crown. These roses also survive today on England football shirts, as well as on English rugby shirts, and the all-British rugby team is appropriately enough known as the Lions.

Such emblems were not confined to nations or to royal dynasties – they were adopted by all major families and by many individuals. Richard II, for example, favoured a number of personal devices in addition to the lions of England and the broom of the Plantagenets: a sun shining, a sun in cloud, a recumbent and chained white hart, and even a tree stump – all of which become woven into the imagery of Shakespeare’s play Richard II.44 This sign language developed its own conventions and traditions, and, by attempting to impose some sort of order and unity on the world, gradually generated its own logic. The symbolism is strangely folkloric – a sort of visual nonsense poetry mixing incongruous elements. Richard’s tree stump, for example, signified Woodstock, a family name; the Lucy family, in contrast, had badges of pike – finless fish that were also known as ‘luces’ – and so their badge punned on their name too. Simultaneously, powerful Christian symbols such as crosses were incorporated into designs, and patterns like the fleurs-de-lys (lilies, the flowers of the Virgin Mary) remain recognizable even today. There is a restless playfulness in this jumble of signs: of blue lions and white harts, foxtails and tree stumps, the crescent moon and seven stars, the shining sun, three leopards creeping by and staring if as one, bugles, seashells, and crowned eagles. Furthermore, they became oddly combined or entangled together when families and dynasties were united in marriage: they could be combined and reworked, as the royal leopards multiplied from two to three, or the Tudor rose grew petals of both red and white, while more complicated patterns could be ‘quartered’ (divided into four, alternating designs between each quarter) or ‘impaled’ (the designs placed next to each other). The resulting strange conjunctions conjured up become almost dreamlike, revealing the symbolic world of the Middle Ages to be teeming with an arcane and fantastical hybridity – and it is out of this dazzling ferment that the Union Jack would ultimately emerge. Some account of this sign language and the laws of heraldry is therefore needed to establish the conventions that govern the national flag, while avoiding the blizzard of technical terms that describe Henry de Percy’s coat of arms, for instance, as ‘azure, a fess of five fusils or’.

Heraldry is a medieval phenomenon that began in dynastic badges. These could be witty or wry, punning or allusive – perhaps recounting like a rebus or visual puzzle a family anecdote or episode – but they also had to be instantly recognizable and unique. Such early insignia – especially those of martial religious institutions – developed rapidly during the Crusades because it was impossible to identify knights and their men-at-arms beneath helmets and armour. The Knights of St John of Jerusalem (a.k.a. the Hospitallers), for example, uniformly wore eight-pointed silver crosses on black fields, and later a red surcoat bearing a white cross; the Knights Teutonic could be recognized by their black crosses on white; the Knights of St Lazarus wore green crosses; and the Templars an eight-pointed red cross on white. The Templars also carried the bloody cross as a banner, but particularly favoured the standard Beauseant: a black stripe above a white field (per fess sable and argent), sometimes combined with the red cross. ‘Beauseant’ (‘Be glorious’) was also the battle-cry of the Templars.*

As indicated by the subtly varied badges of crusading fraternities such as the Hospitallers, Teutonics, Lazarites, and Templars, various different designs of Christian crosses developed: at the height of the Middle Ages, there were almost three hundred variations.45 Other devices were entirely personal: Camden, for example, recounts that at the Siege of Jerusalem, Geoffrey of Bouillon managed to shoot three birds with a single arrow – a feat subsequently recorded on his coat of arms.46 Such signs, patterns, and colours were expressed as an enigmatic language: at once a code confined to insiders and yet also a very public statement of a family’s position in society and place in history. It was the mark – or rather the seal – of their authenticity.