3,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Greg Krojac

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The checkpoint between sectors is bustling with crowds of travellers doing their best to attract the attention of the border patrol staff so that they might have their travel permits authorized and stamped. It’s a waste of time and effort for ninety-nine per cent of them as moving between sectors is strictly prohibited for all except those with special permission from the Colony Executive.

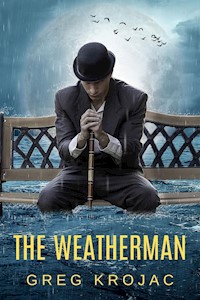

The Weatherman has no such problems. Dressed in a brown two-piece suit, a cream coloured shirt, and wearing a dark brown bowler hat, he is instantly recognisable by border security. Carrying a ridged walking cane in his right hand, he can travel at will between sectors as often as required with no paperwork whatsoever. The border patrol officials know who he is and give him a wide berth. To refuse him free passage would be to risk their jobs – perhaps even their lives.

In this sci-fi thriller with a twist of urban fantasy set on a far distant planet, a teacher from the lowly Sector D, Ooze, stumbles across a strange young woman lost in the fog and is persuaded to leave his uneventful life behind him and join her on a quest. Little does he know that he is putting his life in such grave danger.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

The Weatherman

Greg Krojac

Copyright © 2020 Greg Krojac

All rights reserved

-

This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express permission of the author except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Contact details can be found at the end of this book.

Please note that this book is a work of fiction and any resemblance to persons, living or dead, or places, events or locales is purely coincidental. The characters are productions of the author’s imagination and used fictitiously.

––––––––

Language: UK English

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

PROLOGUE

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

EPILOGUE

THANK YOU

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

NOVELS BY GREG KROJAC

NOVELLAS BY GREG KROJAC

FREE SHORT STORIES BY GREG KROJAC

PROLOGUE

They say that you should never start a story by talking about the weather. Well, I’m going to. Not because I love talking about the weather, but because it’s relevant. It is on this planet, in this colony, anyway. Here, we don’t need weather forecasts. Sector A is always sunny, Sector B always icy cold, it always rains in Sector C, and in my sector, Sector D? Fog – very thick fog. We hate it. But we have no choice. The Colony Executive prohibits us from moving from sector to sector. Even if we could move, we can’t afford to live anywhere else. Most of us would love to move to one of the other sectors, especially Sector A. We’ve heard it’s really beautiful there. But it is what it is.

Who am I? My name is Oositellyi. That’s how you say it. It looks much cooler written down. U-Č-I-T-E-L-J... Učitelj. Difficult to say? Call me Ooze – everybody else does. My name means 'teacher'. Pretty apt really, 'cos that's what I do. I'm a teacher.

My ancestors – back on Terra (or, as some of you may know it, Earth) – were Croatian. In fact, most of us in Sector D are of Croatian descent. Our ancestors came here as refugees during the Great European War of 2353. Croatia got hardest hit. A tragedy really; they say it was a beautiful country. Anyway, those that could get out, did get out and made their way to this hell-hole.

I'm being disingenuous. The planet's not a hell-hole. I hear there are some parts that are quite beautiful. Especially in Sector A, where the richest people live. Sector B too, if you like snow. So I've heard, anyway. Never been there. Sector C would probably be nice too – if it ever stopped raining. And as for Sector D? Nobody wants to come here. And I can't say I blame them.

There are a few Dirties – that's what residents of the other sectors call us – who get to go to the other sectors. We hook up with workers from Sector C, the Shoovers, sometimes, when there's drainage problems in Sectors A or B. Shoovers are great at solving drainage problems – well, they would be, wouldn't they? You need good drainage when it rains all the time. But they don't like doing the dirty work. Not when we Dirties are around to do it for them. So they come into our sector sometimes, recruiting manual labour. Everybody wants to go with them, to take a breather from this bloody fog, but that costs money. Oh – did I not say? They don't pay us; they consider that giving us a break from Sector D is payment enough, if declogging sewers can be called a break. Yet still they get plenty of volunteers. Volunteers who are actually willing to pay them, just for a change of scenery.

I don't volunteer. As I said, I'm a teacher. I'm considered too valuable here to go gallivanting off digging holes and unblocking shitty sewers. I wouldn't want to do it. Anyway, I wouldn't get past the first checkpoint. One look at my hands and they could tell I'm not a manual labourer.

Do you know, I've never seen the suns? Sure, I've seen a couple of fuzzy orange balls in the sky, I mean – they're up there. I know that. They haven't gone anywhere. It's just that this fog is so bloody thick that we Dirties don't get a proper look at them. People who come back from the other sectors – well, A and B – talk about clear blue skies and two beautiful orange glowing orbs that you can't even look at with your naked eye, for fear of burning out your retinas. Here, in Sector D, you can look at them all day long and nothing would happen to your eyes. I know people who've tried it. They can still see all right. Well, they can see about ten metres in front of their noses anyway.

That's our limitation. Ten bloody metres. That's why it takes so long to get anywhere. Transport has to travel slowly, otherwise this place would look like a wrecking yard. That's why we have to go everywhere by public transport. The buses are all fitted out with GPS transponders so they can move around without crashing into each other. No private vehicles in Sector D – it's not allowed. It would cost too much anyway. We're the bottom of the heap; we don't have money to throw around on luxuries like private vehicles. It's walking or the bus for us. Money is for buying food and clothes, and – if we can save enough cash – stuff for our houses. But the transport is free – that's one bonus. They had to provide free transport really; keeps the natives from getting restless.

Housing is free too. It's pre-fabricated and all the houses look the same from the outside. People do try to add a bit of variety by putting different coloured curtains at the windows but you have to be really close to the house to see them properly, so it's a waste of money really. Inside the houses, you can do pretty much what you want. The walls can be any colour you like (like the curtains) but there are only six colours to choose from – red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and white. And there are no differing shades of those colours. There are only six choices of furniture items too. I've heard that in Sector A they have hundreds of items of furniture to choose from and hundreds of colours. That's probably too many really. There is such a thing as being spoiled for choice. I mean, if – say – you want to buy a sofa and there's a whole palette of colours to choose from, not to mention so many different materials, how are you supposed to choose? It's too many choices. But six is too few, too. Even ten would be better than six.

Anyway. Back to the story. My story. You don't need to know everything about this place. Just the basics. You know, to get a feel for the place.

Chapter 1

Every day was like any other day. I came to work, I worked, and I went home again. It was there, and I did it. It was just like my dad used to say when I asked him how work had been that day. He’d say it was there, so I did it. Now I would sometimes say the same. Except my dad was an accountant, and I don’t think he liked his job. I, on the other hand, do enjoy teaching. It’s rewarding. So you can scrub that it was there, so I did it thing. It’s not really applicable.

The day’s lessons were over and it was finally time to go home. I looked out of the schoolroom window and spoke to nobody in particular.

“It’s really bad today. Maybe two metres visibility or less. They’ll have to suspend the buses.”

As if they had been waiting for my cue, speakers all over the city blared out their warning.

Fog Warning. Fog warning. Visibility down to two metres. Public transport has been suspended. I repeat, visibility down to two metres. Public transport has been suspended.

I always thought those words Fog Warning were irrelevant – fog is the only weather we got. We didn’t need a warning about it. Visibility Warning would have been more apt.

Suradnik poked his head around the classroom door.

“You coming, Ooze? You know Služ doesn’t like us to be late.”

Suradnik was a fellow teacher and Služ was the line-leader who would get us home safely that evening.

I gathered up my books, tossed them into my backpack, and left the room, making sure I locked the door behind me and tossing the door keys through the letterbox of the principal’s office. The keys rattled with excitement as they joined those from classes 1B, 2J, and 3S. My class was 4U – ‘U’ for Učitelj. 3S was Suradnik’s class.

It didn’t take us long to get to the meeting point, even though the fog was so thick. We Dirties have a kind of sixth sense that helped guide us through the fog but it was only good for short distances. We needed the walking-lines to get home safely – if the buses weren’t running, that is.

When the fog was particularly bad, the GPS signals had trouble getting to and from the satellite, so everybody had to walk home. No exceptions. It would have been such a recipe for disaster if people were left to their own devices. Imagine two hundred thousand people out on the street at the same time, each one being able to see only two metres in front of their face. There’d be a ton of accidents.

So the city concocted a system of walking lines and each line had two walking marshals. I was one myself. Each pair of walking-marshals had a set number of people to escort home. Everybody who lives close to each other worked close to each other too, so it wasn’t inconvenient. We’d get home later than usual, sure, but it’s better to be late than not get there at all.

My responsibility was for Ulica Street. That’s where Suradnik and I were heading for that evening. It’s in the centre of town, about five kilometres from our suburb. We were lucky that we lived so close. Some people lived up to twenty kilometres away. That journey must have been murder. In fact, it sometimes was. The thick fog was a gift for criminals when it was as bad as it was that day. There were occasionally a few muggings, but it wasn’t unheard of for people to be killed either. That’s another reason why we formed a line of twenty people to walk home – security. Safety in numbers, see?

We quickly passed the red-bricked building that was the Central Bank, the blue-walled Central Clinic, and approached the green metallic structure that was the Central Supermarket. I could see sixteen members of the line had got there before us, including Služ. With Suradnik and my arrival that just left two more spots to be filled.

The two stragglers, new line-members who’d recently moved to the city from an outlying village, had had to kind of feel their way along buildings’ walls to guide them and arrived shortly after us. They’d actually done quite well considering it was their first experience of a two-metre fog. Now everybody had arrived we were ready to set off. I was to bring up the rear, with my red lamp, and my friend Službenik, a clerk, would lead from the front with his white lamp. The white lamp was so other lines could see us. Služ is blind, so he didn’t need a lamp to see where he was going. It made sense for him to lead the line too, as it made no difference to him whether the visibility was two metres, twenty metres, or two hundred metres. He couldn’t see a thing but he always knew exactly where he was going.

Soon the city was a heaving mass of conga-lines (minus the dance moves), twenty people long, weaving in and out of each other with the precision of a military tattoo. Longer lines had been attempted in the past but they’d proved to be too unruly – continually crashing into each other and breaking apart – and so an official limit of twenty had been placed on them. In addition to that, each person was connected to the one in front by a fluorescent cord, so that they didn’t become separated and start wandering around aimlessly and get lost.

Anyway, we all hooked ourselves up – everybody knew exactly where they should be in the line – and waited for the off. The person behind Služ – Mesar the butcher – acted as his eyes to tell him when to set off, counting down as he saw a gap into which our line could slip, but that was the only help Služ needed. He had a special Hi-Vis vest with a giant logo of an eye on it, not to highlight his disability but to advise others to let his line pass as we were able to walk a lot quicker than most of the other lines. He wasn’t the only blind walking marshal in the city but there certainly weren’t enough to go round for every line. We felt privileged to have him heading our line.

So we zigzagged our way along our regular route, everyone fully confident that they’d arrive home safely, stopping occasionally for someone to unhook themselves from the caravan and enter their house. After about forty minutes it was just me and Služ left, the accountant Računovođa having just arrived at her house. I watched her to make sure that she was safely inside the house before we moved off again. Just as Služ was about to start the final leg of the journey, I tapped him on the shoulder.

“It’s okay, Služ. You can drop me off here too.”

Služ didn’t turn round – neither one of us wanted him to lose his bearings – but I could almost see him grimacing, even though I was looking at the back of his head.

“I don’t know, Ooze. The fog’s particularly bad tonight.”

Even though we both had Croatian roots, Služ called me Ooze just like everybody else did. He was one of my best friends and was still concerned about my safety, even though I could take care of myself.

“Are you sure you’ll be alright?”

My first thought was to wonder how he knew how bad the fog was, but he’s blind, not deaf. The city’s tannoys had announced the suspension of public transport services and the commencement of walking lines, so he knew exactly how bad things were. I put his mind at rest.

“I’ll be fine, don’t you worry, Služ. I’m close enough – it’s only a couple of hundred metres from here. I could probably get home with my eyes shut.”

Služ laughed.

“You ought to try it sometime, my friend. It’s not as easy as it looks.”

I patted him on the back as I unhooked my cord.

“I’m sure it’s not, mate.”

As he disappeared into the fog I could just about make out his hand waving goodbye to me.

I wasn’t scared of being on my own in the fog; it really was only two hundred metres to my house and would only take me a couple of minutes or so to get home. The roads were bordered by plants and trees which would have been wasted on us if we tried to look at them from afar but, close up, they brought a little cheer to an otherwise drab neighbourhood. I enjoyed the smell of the flowers and knew each individual plant that grew near my house. I felt perfectly safe as I was (and still am) pretty fit – I used to work out at a gym three times a week – and I liked to think I could take care of myself in a fist-fight so if any mugger had tried to rob me he’d have wished he hadn’t.

I was about fifty metres from my front door when I heard a rustling sound from the other side of the road. I thought I was hearing things until I then heard a voice – a female voice. I crossed the road without looking – one of the advantages of there being no traffic on the streets – and stopped to listen.

There it was again. The voice was weak but definitely human.

“Where am I?”

I followed the sound and a pink-flowered shrub threw itself at my face. The fog must have thickened again as, unusually, it caught me by surprise. The voice spoke again.

“Can you help me? I don’t know where I am.”

I peered through the foliage and saw a young woman crouched down, hiding.

“You’re on Avenija Avenue. In the borough of Varoš. Did you get split up from your walking-line?”

I couldn’t see her fluorescent cord anywhere.

“Where’s your walking-cord? Did you drop it somewhere?

She looked like she might be trying to decide if I was safe to talk to or not – even though it was she who’d called out to me - so I thought I`d better introduce myself.

“Hi. My name’s Učitelj, but people call me Ooze. It's easier for them to pronounce.”

“I can say your name, Učitelj, but I'll call you Ooze too. It's more friendly.”

I grinned.

“I think so too.”

I crouched down so we were on the same level.

“What's your name?”

“Sestra.”

“Pleased to meet you, Sestra.”

Her face looked familiar to me although I’d never seen her before in my life.

“Are you of Croatian descent? Is that how come you can say my name?”

“Yes. My great-great-great-great-great grandparents were Croatian.”

I grinned.

“That’s a lot of greats.”

But what was she doing there, hiding in a bush? One thing was for sure – she certainly couldn’t stay there. It definitely wasn’t a night to spend huddled inside a bush. I made a decision that some might think a bit risky but she looked harmless to me.

“I live about sixty metres from here. Why don’t you come to my place with me? It’ll be safer than staying out here.”

I didn’t know if she’d agree – after all, she didn’t know me from the next guy – but perhaps I have a kind and honest face because she picked herself up from the ground and stood up. Now I could see her better. She was a little shorter than me and was very cute. Yes, that’s how I’d describe her. She clearly had Croatian heritage, a dusky beauty. And cute with it.

Her clothes looked typical of our sector and, especially in the thicker fog, they looked the same as everybody else was wearing – a blouse and slacks combination. There was nothing unusual about the style – it was standard attire for a female in Sector D – but, on closer inspection, the colour was completely wrong. It was a shade I’d never seen before. I mean, I’m no fashion connoisseur, but the quality of the material seemed to be far better than anything we had in Sector D too. Nobody I know had money to spend on clothes like that. Not even Kay the seamstress.

I held out my hand and she shook it, before withdrawing her own hand. I decided that she definitely wasn’t from around here, so I put her straight and took her hand again.

“No. Keep hold of my hand. This is the worst fog I’ve seen for a long time. Maybe one metre’s visibility, now. You need to hold onto my hand so we don’t get split up and you end up getting lost again.”

She looked embarrassed.

“Oh, sorry. I’m not used to the fog.”

Where had she been living? Under a rock or something? How could anybody not have been used to the fog? It’s the only thing we could be sure of in Sector D, that each day would bring fog. Not only was she not from the city but I suspected she wasn’t even from this sector.

We arrived at my front door and I pressed my right palm against it. The door clicked open and we went inside. She seemed a bit surprised at the airlock.

“What’s this?”

“It’s an airlock. Without it, everything inside the house would be damp and clammy. It’s bad enough that there’s fog outside – we don’t want it to get inside the houses too.”

The interior walls of my house were green. I like the colour – it’s quite relaxing – but there was only a choice of six colours anyway. I could only afford one two-seater sofa, but I had four large green beanbags which gave guests something to sit on, without having to squeeze up against me on the sofa.

“Welcome to my humble abode, Sestra. It’s not much – but it’s all mine.”

“It’s nice.”

I think she was just being polite. My place was very basic. And I mean very basic. Just the necessities. The sofa and beanbags, of course, plus a web-vision set that was on its last legs. I have no idea how it was still functioning. I’d had it repaired so many times and each time I took it to Popravak, the repair-man, I expected him to suggest a funeral for it, but somehow he always worked his magic and breathed new life into it. The guy’s both a magician and a lifesaver. The kitchen had a microwave oven and a hob for cooking – not that I used it much. Plus a fridge. I didn’t use that much either. I found the morning inhalation of životnu maglu – or Zima as we called it – processed life-mist, provided me with all the nutrients that I needed. It sounds like a drug, I know, but was our staple form of sustenance here in Sector D. I wasn’t a junkie. Okay, I’d taken Lonac a few times – so would you have done if you’d lived here – but it’s completely non-addictive. It`s not like Pukotina which, once it gets its claws into you, is very difficult to shake off. The majority of muggings that took place in Sector D were committed by Pukotina addicts needing money for their next fix.

The shower room/bathroom was probably the nicest room in the house. I recently had it refurbished and it still looked like new, with a pristine white toilet bowl, matching sink unit, and shower cubicle. I even hid the shower’s wiring inside the wall – not a common thing in Sector D. It took me three whole years to save up enough money to have the bathroom renovated and I was proud of that room. And finally, of course, I had a bedroom. Comfortable but not extravagant. A single bed, a wardrobe, and a painting on the wall. I’ve no idea what it was supposed to be but I liked it. That’s it. As I said, basic.

It was no different to anybody else’s house really. When people got married they were given a slightly larger house, and then when they had children a slightly larger one still – that’s if the children survived the first year. The fog wasn’t poisonous but it brought with it bronchial problems for many infants. One of the sad facts of life that came with living in Sector D.

I sat on one of the beanbags, allowing Sestra the comfort of the sofa. She was a guest, after all. She sat there just looking at me and, if I hadn’t broken the silence, we might have spent the whole night just looking at each other.

“So, Sestra. Where are you from? You’re not from here, I know that much. You’re an Otherlander, aren’t you?”

The Otherlands are what we call the other sectors, and – ipso facto – anyone who isn’t from our sector is known as an Otherlander. It works in the opposite direction too; to Sestra I was an Otherlander.

She wrinkled her nose.

“Is it that obvious?”

“By your looks, no. But you didn’t know how to handle the fog and everybody from Sector D knows what to do when the fog gets this bad. We’re taught it as kids. I don’t remember but we’re probably taught it before we can even talk. It’s a question of survival.”

I pointed at her clothes, an ill-fitting plain coloured blouse and matching slacks.

“And that’s not the type of thing we can get hold of here, either.”

She looked confused.

“It looks like yours.”

“They look similar, yes, but nobody here can afford that quality of material. And what’s the colour of your blouse?”

“It’s maroon.”

“I like it. I just haven’t seen it before.”

Sestra looked at me as if I’ve discovered her big secret, but she had bigger secrets than that.

“Can I trust you, Ooze?”

I pride myself on being a trustworthy kind of guy.

“Of course.”

Secret number two was about to be disclosed.

“I’m from Sector A.”

I didn’t know how to react. I’d never met a Sunčano before. I was speechless. She waved at me to bring me back to the land of the living and I found my voice.

“You’re really from Sector A?”

“Yes. And I’ve never met a Dirty – sorry, I mean I’ve never met a Najniža before. I didn’t mean to offend you.”

Najniža was our official name, but it wasn’t much better than the word dirty – it meant ‘lowest’. We were much kinder with our names for Otherlanders. People from Sector A were Sunčanos (which meant sunny) and their nickname was Solsters. People from Sector B were Snijegs (which just meant snow) and were known as Icers. Sector C people were Kišas, meaning rain. We called them Shoovers. It was only us from Sector D who were given an offensive name. We should really have been called the Magla – meaning fog – but the names Najniža and Dirty just showed the contempt that Otherlanders held us in. Unless they wanted their drains cleaned, of course.

So, Sestra was an Otherlander, a Sunčano, but that didn’t explain what she was doing so far from home.

“Why are you here, Sestra? I mean, in Sector D? You’re a very long way from home.”

“Well, I’m not on holiday. No offence, Ooze, but nobody comes here by choice.”

I wanted to defend my sector against the insult, but she was correct. Nobody in their right mind would leave their sector to come to ours. Not unless they had to.