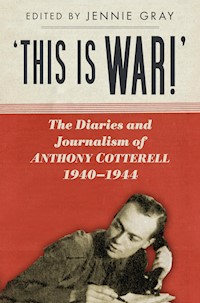

'This is WAR!' E-Book

13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Spellmount

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Anthony Cotterell wrote a unique form of war journalism – witty, sharp,engaging, and so vivid it was almost cinematic. As an official British Army journalist during the Second World War, he flew on bombing raids, sailed with merchant shipping convoys, crossed to France on D-Day, and took part in the Normandy Campaign. During this time he kept a diary, a hilarious and caustic record of his role in the war, a diary which abruptly ended after he vanished in mysterious circumstances after the battle of Arnhem bridge in 1944. Cotterell's diary and selected war journalism, illustrated with previously unpublished photographs, are presented together here to shed new light not only on the everyday life of the British Army in the Second World War but also on the role of the press during times of conflict. The quality of his writing is truly captivating and his account of the Normandy campaign is surely the nearest that a modern reader will ever get to experiencing what it was like to be in the thick of a Normandy tank battle.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Cotterell was emphatic that our first publication should be called WAR because it afforded the opportunity to answer the telephone with the words ‘This is WAR’, which are susceptible of a variety of dramatic enunciations.

Stephen Watts, Moonlight on a Lake in Bond Street

CONTENTS

Title Page

Epigraph

Acknowledgements

Anthony Cotterell, War Reporter

About the Texts

PART ONE: THE RELUCTANT SOLDIER, March 1940– June 1941

The Reluctant Soldier

What! No Morning Tea?

‘First Week, Friday: Off the Deep End’

Easter Sunday

‘Fourth Week, Tuesday: Oh, Bad Shot’

‘Sixth Week, Monday: So Many Men’

The Signaller

Officer Training

Oh! It’s Nice to be in the Army!

‘Why Does He Shout So Loud?’

‘Life is Very Different as an Officer …’

‘Defending the Realm’, Diary, January–March 1941

Defending the Realm

Motor Liaison Officer

Diary, March–April 1941

‘A Night at the Staff College’

‘Wednesday: I Went Down to the Garage …’

PART TWO: REPORTING FOR WAR, June 1941–September 1944

Reporting for WAR

‘And What Did They See?’

‘Lines of Thought’ (Editorial)

‘Once Round the North Sea’

‘Same Way, Different Ship’

Parachutist

‘The Sergeant’s High Jump’

With the Airmen

‘Ships that Pass in the Day’

‘Did I Ever Tell You About My Operation?’

RAMC

Malingerers

‘French Farce’

Fusilier William Close

D-Day

Prelude to D-Day, Diary, 20 May–5 June 1944

‘A Day at the Seaside: Going on Shore’

With the Sherwood Rangers in Normandy

With the Tank Crew

The Battle of Fontenay-le-Pesnel

‘Down by the Beaches Where the Minefields Lay …’

‘An Operation was Performed’

With 1st Parachute Brigade

‘Airborne Worries: Waiting to be Scrubbed’

Appendix

Military Abbreviations

Anthony Cotterell Works Used in the Book

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is the twin, so to speak, of my 2012 biography of Anthony, Major Cotterell at Arnhem, a War Crime and a Mystery. The research for the biography provided the framework for this edited edition of Anthony’s writings, and the full acknowledgements, bibliography and sources for both volumes can be found in Major Cotterell at Arnhem.

I would like, however, to acknowledge here the additional help given by Anthony’s cousins Rosemary McGrath and Robert Crews in the attempt to positively identify Anthony as being the man standing to the right of Stanley Maxted in the AFPU footage taken immediately prior to Arnhem (see photographic section). Although no documentary evidence has been found, it is extremely likely that this was indeed Anthony. His presence in the AFPU footage was first spotted by Andrew Reeds in his own research on the Arnhem PR coverage, and I thank Andrew for generously sharing his observation.

ANTHONY COTTERELL, WAR REPORTER

Anthony Cotterell wrote a unique form of war journalism, witty, sharp, engaging, and so vivid that at times it was almost cinematic. His style was deceptively stripped down and simple, seemingly very easy to imitate. However, its powerful effect was due to a masterly skill in choosing the right materials. The telling anecdote, the brief but evocative description, the perfect choice of dialogue between his fellow servicemen – these are some of the things which gave his work its inimitable quality.

There are two main reasons why his name has not been widely remembered. Firstly, it was the radio journalists of the Second World War who have attained iconic status in history, such men as Quentin Reynolds, Stanley Maxted and Richard Dimbleby. War reporters whose medium was the printed word, such as Alan Morehead, Alexander Clifford, and Anthony himself, have fared less well in historical memory. Secondly, much of Anthony’s most successful writing was about the Army, and as such did not have a permanent interest for the wider public although its value is now being rediscovered by historians.

Anthony reported not just on the blood and thunder stuff, the stirring and thrilling campaigns, but the minutiae of everyday life in the Services, being in a unique position to do this as a serving officer. The picture which he gives of fighting men is very far from gung-ho heroics; he spotlights real people and uses the actual words which they speak, thus giving his work a high degree of realism. Above all, he has the ability to make his readers feel that they are actually there with him at the scene. To take one example, his account of the battle of Fontenay-le-Pesnel – this is surely the nearest that a modern reader will ever get to experiencing what it was like to be in the thick of a Normandy tank battle.

Anthony’s reports of D-Day and the Normandy campaign were the summit of his reporting career. Less than three months later, he went to Arnhem with 1st Parachute Brigade, and was amongst the small force which got to the bridge. As is well-known, Arnhem was a colossal military disaster, and it was in the chaotic aftermath of the battle that Anthony somehow lost his life. After the battle was over, he and several other British officers at the bridge were captured by the enemy. On 23 September 1944, they began the long journey to imprisonment in Germany. Along the road, in the Dutch village of Brummen, two of the British officers escaped from the truck in which the party was being transported. This precipitated a terrible incident in which two members of the SS shot up the remaining unarmed prisoners in the truck. Three were killed outright, and three were seriously wounded, including Anthony. He was treated in a German dressing-station in Zutphen in Holland, but subsequently disappeared without trace, the only one of his party to do so. To this day his fate remains a mystery. The full story of what happened can be read in my book, Major Cotterell and Arnhem: A War Crime and a Mystery. Had he lived, Anthony’s account of Arnhem would have been a masterpiece, and the definitive story of what happened at Arnhem bridge.

Anthony was not a career soldier. When reluctantly conscripted in March 1940, he was a twenty-three year old staff reporter on the Daily Express, at that period the most dynamic and lively of British newspapers, with the world’s highest daily circulation. Anthony had won his staff post at the early age of seventeen and was all set for a high-flying career in journalism when the war intervened. He saw conscription as a levelling process, in which the distinctions one had earned in civilian life were brutally stripped away and everyone was reduced to the same lowly, slave-like status. Then, slowly and painfully – if one was lucky and had a talent which the Army could use – one worked one’s way back up again. In Anthony’s case, it took fifteen months before the Army recognised his brilliance as a witty and engaging commentator on military matters and gave him what amounted to a plum job, together with considerable latitude to pursue his journalistic career. However, he always remained to a large extent a cynical and sharp-eyed outsider, albeit one who acquired the most tremendous respect and admiration for fighting men. In his Army diaries and journalism, he would always bear in mind the harried private, then the even more harried junior officer that he once had been; this gave his writing an immense humanity, and was one of the reasons why he became such a successful commentator on Army affairs.

The diaries and extracts included in this book fall into two distinct parts. The first part relates to Anthony’s first fifteen months in the Army, which were frequently very unhappy; the second part to his three-year attachment to the War Office, where in a department called ABCA (the Army Bureau of Current Affairs) he at last found himself the perfect Army niche.

Part One begins with Anthony’s life as a new conscript. The first four extracts come from his book What! No Morning Tea?, which was based upon a diary which he kept from March to May 1940. The original version of the diary has been lost and what survives has been tailored for public consumption. Anthony always edited his diaries when he used them for published work, and in this case the entries have a buoyant, positive tone which disguises the true painfulness of his experiences. As always with Anthony, the result is entertaining and informative, but the private man has disappeared behind the jaunty self-portrait necessary to make the book a commercial success.

The same is true – though rather less true – of his accounts of his training as a signaller and then as an officer. The extracts used here come from his October 1944 book An Apple for the Sergeant, which was also based upon a contemporary diary. By the time that An Apple for the Sergeant was published, Anthony had established his role in the Army so securely that he could pretty much say anything he wanted. He thus freely admitted several of his past military delinquencies without the slightest shame or any fear of the consequences. His service persona was always a key part of his writing, and in these particular accounts he makes his laziness, disenchantment, and complete uselessness as a conventional soldier part of the comedy and absurdity of military life.

The longest text in Part One is the diary which has been entitled here ‘Defending the Realm’. It is for the most part taken from the typed transcript of the original diary and, therefore, is much closer to what Anthony really thought. It concerns the period when he was a very junior officer in an infantry battalion, and extremely unhappy and discontented. Being in the Army had become something to endure, a prison sentence which had no known end, and the fact that the Army was not actually doing any fighting meant that the sacrifice of his personal freedom had come to seem extremely pointless. His journey from the raw conscript of March 1940, who had tackled his seismic change of lifestyle with considerable wit and courage, to the resentful officer of early 1941 could almost be said to be a sort of ‘Conscript’s Progress’, paralleled in the experience of hundreds of thousands of other Army conscripts at this particular stage of the war.

The progress of the war had had a severe effect upon Army morale. Very briefly summarised, the quiet period known as the Phoney War had ended during Anthony’s first weeks in the Army. From April 1940 onwards, events on the Continent moved with lightening speed to a catastrophic conclusion. Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg all fell under Nazi control. On 22 June the so-called Armistice was concluded by the Germans with the Pétain government in France, and Britain’s war strategy lay in ruins.

Much of the British Expeditionary Force had come home from Dunkirk, but this was the last fighting that the bulk of the Army was to see for years. Instead, the war took to the sea and the air. As the only role that the bulk of the Army was likely to have for the immediate future was a defensive one, boredom, demoralisation, and numerous tiny rebellions against military authority became endemic features of military life, a reaction to the lack of purpose and the ceaseless, apparently pointless training. As Anthony wrote:

Military training is one long charade. You have to be able to pretend that live men are dead and dead ammunition is alive and take the consequent military problems to heart.1

‘Defending the Realm’ gives a fascinating insight into a side of Britain’s war which is rarely covered – the disenchantment, shading perilously close to demoralisation, of many conscript soldiers at this period. Men whose normal peacetime lives had been violently torn apart could stand that disruption if they felt that their presence in the Army was vital. What undermined them was that nothing seemed to be happening, not even the threatened German invasion.

Their discontentment did not pass unnoticed – the top brass were becoming increasingly concerned that the troops’ morale, commitment and effectiveness were being eroded by the lack of any purposeful activity. One of the ways in which they planned to remedy this was through Army education, and, in fact, it was for exactly that area that Anthony would be hand-picked in June 1941. He had, of course, no idea that this would happen when he was writing ‘Defending the Realm’ between January and March of that same year.

What changed everything was his book, What! No Morning Tea?, which was published in January 1941. Its tale of how an incompetent conscript became a passable soldier was a huge success. Despite saying many things which were anathema to conventional military types, the book’s message – that soldiers were human and that conscripts should be treated as rational, sentient beings – chimed perfectly with the concerns of early 1941. Within two months of its publication, the book had become recommended reading for Army officers. Within five months it had come to the notice of the big guns in Army welfare and education, who then arranged for Anthony’s transfer to the War Office. In June 1941, Anthony became part of what was soon to be christened ABCA and his role in the Army was radically transformed.

Part Two of this book covers the reporting which he did whilst at ABCA. Working for ABCA enabled him to take a panoramic view of the war and brought him into a close acquaintance with the cream of the British armed forces. As Britain’s fortunes in the war gradually changed, it was ABCA which gave him the pass into various fields of action, culminating in the world-changing events of D-Day and the Normandy campaign. Finally, it led to him parachuting into Arnhem with 1st Parachute Brigade in September 1944.

Throughout his time at ABCA, Anthony worked on the fortnightly bulletin, WAR, a small pamphlet-sized publication with a glaring red cover which supplied raw material to education officers. The idea was that by using WAR these officers could give a lecture, then chair a discussion and generally get the troops motivated by the key issues behind the war. As a top general told Anthony just before he joined ABCA, the bulletin had the approval of the highest military authorities – ‘We want to get rid of this pernicious idea of we can take it. Stop being passive and turn aggressive.’2

WAR’s claim that it was written ‘by soldiers for soldiers’ was entirely true. Mindful that pedantry would not impress the troops, the authorities deliberately selected two ex-journalist soldiers who had worked in the popular press to write for WAR, the first being Anthony, the second being Stephen Watts from the Sunday Express. Their first issue was published on 20 September 1941 under the subtitle ‘News-Facts for Fighting Men’. All the articles in the first two issues were anonymous, and the overall style of the publication was brisk, soldierly, and no-nonsense. Even so, the two ex-journalists were incapable of writing a completely dull piece. Parts of the editorial were written in a deliberately informal, modern, personal style, with short sentences which had no verbs or which commenced with ‘But’ and ‘And’, this being one of the dominant styles at the Express.3 Although their names did not appear, Anthony and Stephen referred to themselves as ‘we’ rather than writing in the third-person or indeed no identifiable person at all. They made their promise to the readers and sided with them.

A word about the campaign stories. They are not dispatches hot from the battlefront. WAR is not competing with the newspapers. But what we can and will do is to give you a complete picture of the campaign. And that is possible only when all the information has been received, collated and edited. That takes time.4

Tracking the editorial (or, as it came to be named, ‘Lines of Thought’) through the ninety-seven issues of WAR is a quick and easy way of identifying the publication’s change of tone. Initially it could be rather admonitory, speaking with the official voice and in the official language of ABCA’s formation. However, over the course of three years WAR changed dramatically. By the D-Day issue, the no-nonsense briskness had gone, and to a large extent so had the official justification for WAR’s existence, i.e. the provision of material for group discussions. The D-Day issue was unashamedly a news issue, with virtually no attempt to turn Anthony’s account into discussion material. As he wrote in the very short accompanying editorial piece:

The 6th June, 1944, is a date that will live in history with Trafalgar, Waterloo, and the Dardanelles landings. These accounts of what happened then are of interest if they are simply related to your men as straightforward narratives.5

WAR had, in fact, gradually acquired something of the nature of a small magazine, with varied and interesting content, much of it relating to various exciting campaigns rather than the humdrum practical stuff. From the end of 1943, it was carrying increasingly lengthy and frequent articles by Anthony, all of which appeared under his own name; his report on the D-Day landing, for example, ran for nine small-type pages, almost the entire issue. Anthony had become the star reporter as well as the editor of WAR, and he had modified the original ABCA official brief to suit himself. He went where he wanted, wrote what he wanted, and only later tacked on a small amount of ABCA window-dressing.

Ernest Watkins, who was Stephen Watts’s successor, gives a very clear picture of how Anthony had made WAR his personal fiefdom.

By 1943 Anthony was in complete control of WAR. Nominally the two sections of ABCA responsible for publications were in charge of a lieutenant-colonel answerable to Williams and through him upwards to the Director of Army Education and on to the Adjutant-General himself.6 In this respect, the Adjutant-General resembled a Fleet Street press baron […]. He had the power of instant dismissal. But he did not interfere with WAR. Nobody did. There was no editorial board, not even an advisory committee. Anthony decided what went into each issue, how it was handled and what lessons were to be learnt from it. For a military publication in wartime, it had a most unusual degree of independence.7

During the course of four short years, Anthony changed from an embittered (and frequently almost intolerably depressed) conscript who thought he had lost his journalistic career forever to a highly successful writer on Army affairs who brilliantly exploited all his opportunities. In working for WAR, he also worked for himself, collecting far more material than could ever be used in that publication and reserving it for the books which he wrote or planned to write.

His superb journalism was widely acknowledged. Stephen Watts greatly admired Anthony’s gift for capturing a scene – ‘Anthony’s eye and ear for the significant line or moment were deadly’.8 Ernest Watkins wrote that what made Anthony’s writing so distinctive and memorable was ‘the occasional unexpected flickers of his own personality. I thought of them as eddies on the surface of a swift flowing river, indications of its depth, its third dimension.’9

That Anthony’s very individual style of writing was considered an essential part of WAR’s success was summarized by the man ultimately in charge of WAR, the Adjutant-General, General Sir Ronald Adam, one of Britain’s top soldiers. Adam wrote in his farewell message to WAR in June 1945:

I should not like to conclude this message without some reference to Major Anthony Cotterell. […] He believed that you could best describe a thing only after you had done it yourself, and it was to give you the best account that he flew with the USAAF, landed in Normandy on D-Day, and qualified as a parachutist. Many gallant men have lost their lives in this war, and I think this is the right place to mention this one.10

1 Anthony Cotterell, An Apple for the Sergeant (Hutchinson and Co, London, 1944), p.32.

2 The top general was the Director-General of Welfare and Education, Major-General Harry Willans. Anthony Cotterell, An Apple for the Sergeant, p.93.

3 ‘It has been said, only half in jest, that in a Beaverbrook paper a paragraph consists of no more than six lines – it always begins with “and” or “but”.’ R. Allen with John Frost, Voice of Britain, The Inside Story of the Daily Express (Patrick Stephens, Cambridge, 1983), p.70.

4 ‘Lines of Thought’ (Editorial), WAR, issue 1, 20 September 1941 (ABCA, The War Office), p.2.

5 ‘Lines of Thought’ (Editorial), WAR, issue 74, 8 July 1944, p.2.

6 Williams – William Emrys Williams, a civilian, had been taken on at ABCA because of his flair and expertise in educational matters; he was one of the most distinguished of a number of educational specialists who had been drafted into the War Office for the duration.

7 Ernest Watkins, ‘It Is Dangerous to Lean Out’, Ernest Watkins papers, Special Collections, University of Calgary, file 5.1–5.2, Accession Number: 469/90.9, p.159.

8 Stephen Watts, Moonlight on a Lake in Bond Street (The Bodley Head, London, 1961), p.112.

9 Ernest Watkins, ‘It Is Dangerous to Lean Out’, p.167.

10 General Sir Ronald Forbes Adam, ‘The End of WAR, a farewell message from the Adjutant-General’, WAR, issue 97, entitled ‘Swan Song’, 23 June 1945, p.2.

ABOUT THE TEXTS

After his death, Anthony’s unpublished papers were preserved by his younger brother, Geoffrey Cotterell, who had been extremely fond of his brother and was devastated by his loss. Geoffrey dedicated an immense amount of effort in the immediate post-war years to finding Anthony; a very considerable amount of help was given by the Dutch, and a parallel search was conducted by the British War Crimes Group for North-West Europe. Sadly, Anthony’s disappearance remained a mystery. Geoffrey carried a lifelong burden because of the entirely forgivable failure to find his brother’s body or to discover what had happened to him. He kept Anthony’s papers almost as an act of piety, a connection with the much-loved past. He also preserved them because, as a writer himself, he might one day want to use them as raw literary material.

Nonetheless, Anthony’s papers clearly have large gaps in them. By the time I met Geoffrey in 2008, he was living in a shambles, in a very untidy and disorganised flat in Eastbourne where everything was unkempt and covered in dust. His health had been poor and he had recently had a hip replacement – keeping things immaculate was not exactly a priority. As he was then in his late eighties, Social Services had become involved, and it seems that in one of their bouts of tidying up they disposed of various dusty papers, to their mind valueless, which had been left lying around. At one stage there was a cuttings book of Anthony’s newspaper articles, but by the time I asked to borrow it, it had disappeared. Geoffrey was very contrite, apologising for ‘such monumental carelessness’. Thankfully, before that particular purge he had given me a huge box of Anthony’s papers, amongst which was the D-Day and Normandy material in this book, together with the drafts for ‘Defending the Realm’.

It is impossible to know now how much material was disposed of by Anthony himself, by his family, or by accident in later years. Clearly the material was severely edited at some stage, because the only surviving personal letters (apart from one to Anthony’s old journalistic mentor, George Edinger) are a handful from Anthony’s first year in the Army.

Because Anthony disappeared after the battle of Arnhem, his papers were left in a very disorganised state and became even more so over the next sixty-four years. The Normandy papers, in particular, were in a confused mess, in multiple drafts with no page numbers or titles; the only aids to making sense of them were the very rusty paper-clips which fastened some together.

Jumbled up in the mess of papers was the only surviving fragment of the extensive handwritten diaries upon which Anthony based his books and articles. Written in 1941, just before he joined ABCA, it gives a unique insight into the type of diary entries which Anthony wrote before he began the filtering, reshaping, and writing-up process which resulted in a finished piece of work. The ruled pages are very small and covered with neat writing in blue ink which fortunately has not faded like the yellowing paper. Each page has punched holes to fit Anthony’s tiny trouser-pocket file, the method of diary-keeping which he used throughout his Army career.

When composing books and articles from his diaries, Anthony had a distinctive working method. He extracted what he wanted from the source diary and then discarded it as if by itself it had no intrinsic value. Apparently he also did not keep the typed transcripts of the diaries which were part of the working-up process. However, in the case of An Apple for the Sergeant, published in October 1944, some of these diary drafts still exist, possibly because he did not have time to dispose of them before he went to Arnhem, or possibly because these drafts alone survived the vagaries of the next sixty-four years.

Although the way in which Anthony worked up the material often added new, very interesting details, it also frequently destroyed the immediacy and freshness of the original writing which, in my view, is of the greater interest today. I have, therefore, always used the earliest version of any text, although I have often added in sections from the later versions. The loss of spontaneity is particularly marked in cases where the end result was an article in WAR. Because of the need to condense and to sound authoritative, much which was of great interest was deleted as being unsuitable for the publication. For example, Anthony usually removed men’s names and called them by their role or their rank instead, e.g. Brigade Major, Corporal, Flight Lieutenant, and so on. He took out the worst swearing, thus rather taming the way that soldiers speak, and understandably he also cut out anything which might be too revealing of military secrets. Lastly, he removed his most amusingly sarcastic and militarily unacceptable opinions, being cool-headed enough to know that at WAR he was in a highly privileged and responsible position.

The WAR article which was based on a section of the Normandy material is a good example of this editing process. The article was called, ‘Tiger, Tiger, Burning Bright’ – a typical Anthony play on words, referring to the much-feared German Tiger tanks and the way in which the tank war often ended in conflagration.1 The original typescript has a lot more information and is far more exciting and direct than the WAR article. However, there are also a number of errors or blank spaces in the typescript where Anthony was temporarily lost for a word or did not know some piece of military terminology. Where possible the two texts have been cross-referenced, and gaps or omissions filled in. I have also done this for other texts where more than one version exists.

Further to the unpublished D-Day and Normandy material, in several places it is obvious that Anthony was reading his notes out to someone who later typed them up. There are a number of small errors where the wrong word is used but one which sounds extremely like the right one. Anthony would shortly tell an interviewer, John Paddy Carstairs, that he was ‘cultivating dictation’, and that this helped ‘to solve the equation between mental activity and physical translation on to paper’.2 The method must have helped in getting the text down quickly, but it is clear from the various mistakes that there was no time to check it properly before Anthony went to Arnhem. In particular, whoever was taking down the text often made mistakes with military terminology. For example, ‘sometimes tracer would drift in our direction’ became meaningless when the word ‘paper’ was substituted for ‘tracer’. In another place, where Anthony clearly meant ‘Tiger’, the German tank, the typescript reads ‘fighter’. I have corrected such mistakes wherever they are obvious.

In early drafts where words are missing, I have guessed when the meaning is clear. Otherwise, I have omitted the gap altogether, or in the most impossible cases used a ‘—’ to indicate the space. Other editorial decisions taken were not to use square brackets or ‘…’ in places where the text has been cut, and not to footnote the different versions used. These decisions have been made in the interests of readability, because with multiple versions being used, the text would soon end up looking like Spaghetti Junction. I have added paragraph breaks where necessary to clarify the meaning. I have standardised the capitalisation of military ranks and written out the full version of Army acronyms in most cases, or occasionally footnoted them.

An Apple for the Sergeant, from which several texts have been taken, bears many signs of having been put together in something of a hurry and not very scrupulously edited. In particular, tenses sometimes go astray. Anthony usually wrote in the present tense in moments of high drama like the bombing trips, so I have tidied up incidences where he uses the past tense in the middle of an otherwise present tense section.

In all this I have tried to keep as close to the original text as possible but the one place where I have been forced to take a slightly more laissez-faire approach is in the Normandy texts. I have always used the earliest version as the template and inserted chunks of the later versions where they are necessary to complete the story.

Jennie Gray, Editor

1 ‘Tiger, Tiger, Burning Bright’, WAR, issues 76 and 77, 19 August and 2 September 1944.

2 John Paddy Carstairs, Hadn’t We the Gaiety? (Hurst and Blackett, 1945), p.34.

PART ONE

THE RELUCTANT SOLDIER, MARCH 1940 – JUNE 1941

THE RELUCTANT SOLDIER

I n March 1940, Anthony was conscripted into the British Army. He did not want to be a soldier but faced it reasonably stoically as inevitable.

The book which he wrote about his first eight weeks in the Army, What! No Morning Tea?, begins at the exact point when he received his call-up letter, which had been anticipated for many weeks.

I was just putting the lead on the dog when our maid Daisy gave me the letter.

I took one look and knew. This was it. And it was.

A railway voucher, a postal orders for 4s, and some orders.

For the first time since I left school someone was giving me orders which I couldn’t walk out on or argue about.

I really laughed. The whole thing was so awful, it was funny. Everything you had ever worked for was sent up in smoke by that halfpenny circular. Every hope, every plan.

Not that I had anything in particular against the Army. But I was comfortable and I didn’t want to be disturbed. An unconscientious objector.1

The one bright spot, as Anthony saw it, in his forcible induction into the Army was that he was in the first group to be called up under the National Service Act. As an Army colleague later commented, this gave Anthony a great deal of satisfaction: ‘The Government was giving him the chance to cover at first hand an event of the greatest interest to the public, and this he was prepared to exploit to the full.’2 As soon as Anthony received the call-up letter, he began to keep a diary, and it was this diary which would form the basis of his best-selling book on conscript life, What! No Morning Tea?

The call-up letter arrived on 9 March 1940. This was a Saturday, and he had only six days to put his affairs in order. On Friday 15 March, he left the life which he had lived for the previous six years to travel down to a barracks at Dorchester and his new life as an infantry private.

1 Anthony Cotterell, What! No Morning Tea? (Victor Gollanz, London, 1941), pp.9–10.

2 The colleague was Ernest Watkins, who worked with Anthony at ABCA. From his unpublished autobiography, ‘It is Dangerous to Lean Out’, p.158.

WHAT! NO MORNING TEA?

‘First Week, Friday: Off the Deep End’

I caught the 8.30 a.m. from Waterloo.

The train was packed with young men all carrying attaché cases and mostly hatless. Like football teams and with the same aura of nervous anticipation.

The general standard of dress and appearance was extremely good. Shoes had been shone, faces scrubbed, trousers pressed, hair slicked back. You couldn’t see who had been a clerk and who had been a navvy.

I got a corner seat. There were four other conscripts in the compartment, and an old lady going to stay with her married sister in Portland.

There was very little seeing off, and it was very restrained. ‘Good luck, boy.’ ‘Look after yourself, lad.’ One man in our compartment had his father, mother and sister on the platform. There was no sign of the wrench except the death-house intensity of the mother’s last-minute kiss, and the father’s ‘Write and let us know ‘ow you get on, son.’

It was a perfect spring morning, but the country scenes racing past the windows were not appreciated. ‘All fields, ain’t it?’ and ‘Couldn’t ever stand it; nothing to do.’ We were all desperately anxious to be friendly. It was ‘After you’ and ‘Have a fag’ all the time. There was a lot of conversation; bewailing our fate fervently but not bitterly. And all those jokes about the Sergeant-Major.

They talked of the parties they had had. ‘Twenty-three in the room. I spent thirty bob and there were others spending. Had to carry the bottles from the pub in baskets.’ And the quantities of beer they were going to drink. Presently they went out for a drink and came back half an hour later with a sinister customer called Danny. They started playing solo.

I didn’t feel like drinking. I had a flask of brandy but didn’t want to face the problem of whether or not to share it. I ate a plum, a pear, an apple for breakfast. I felt melancholy rather than miserable; but not very much of either: and surprisingly no physical excitement.

We got there about 12.30. About 200 got out of the train. We were led off by an NCO, shambling down a subway like convicts, and watched by other passengers with the same fascinated horror that people watch convicts. Our first sight of the place was not particularly attractive, though of course it isn’t fair to judge a town by its station yard. The main feature of the view through the coal trucks was Messrs Eldridge and Pope’s neat but not breath-taking brewery. We walked down the station yard, past a small and empty market, and up a villa-lined hill.

After about ten minutes’ march we arrived in sight of the barracks; the entrance was impressively medieval. A turreted grey stone heap with an archway entrance through which we could see a giant quadrangle lined with red-brick barrack buildings. We queued up under the archway to have our names ticked off on a list. We straggled sheepishly across to an ominously well-equipped but well-heated gymnasium where we queued up to be sorted into batches under whatever sergeant God had in store. It was getting on for 2 p.m.

Our sergeant turned out to be a very pleasant, soft-spoken, stocky West Country man. He marched us along one side of the barrack square, out the other side, down along a road and turned right down a hill lined with big barrack huts on one side and miscellaneous buildings and tall trees on the other. About three-quarters down the hill the Sergeant led us off the road, up a little path to our barrack hut.

There are fourteen huts in a line down the hill. They are about 60 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 20 feet high. They are stained various shades of brown, and about 15 feet apart. The entrance is half-way down one of the 60 foot sides. There is a wooden porch and a green door. Just inside the door there are three fire buckets of water and one of sand.

There is accommodation for twenty-four men. There is a large locker supported on wooden brackets above each bed. They provide plenty of room for anything you are likely to have. Underneath each locker there are four hat and coat hooks, but these are used for military equipment. There is a towel rail on the side of the locker and a hook for the greatcoat.

The beds are iron frame affairs which you pull out for the night. They have a good but hard mattress and an under-sized cylindrical pillow. The general atmosphere of the hut is roomy and airy. It is heated by hot-water pipes. On the corporal’s advice I took a corner bed just by the door.1 I forgot to see if it was properly lighted, and it wasn’t, but it did at least provide a certain illusion of privacy.

Each room has a corporal who sleeps in one corner. Sergeants sleep elsewhere, sharing rooms of their own. Our corporal was a slim, rather solemn-looking young man who looked about thirty. Like everyone else he was very concerned to see us comfortable, very eager to answer questions, several times assuring us that if we played the game by him he would play the game with us.

We were marched up to the stores hut to get four blankets, a large china mug, a knife, fork and spoon. Then back across the barrack square into a two-storey red-brick building and up the stone stairs to lunch. Two from each table went to collect the food. The food is served in tins. You queue up at a counter and it is slammed across at you by noticeably well-fed warriors. You take it back to your table and dish it out; and those who dish it out never go hungry.

On this occasion it was stewed meat, potatoes and beans; followed by stewed apples in gelatinous custard.

It was no worse, no better than I expected. I ate it greedily. In the face of this dramatic change of life, normal critical standards are almost completely suspended. The fact that the bread is piled on the table and passed by a series of hands doesn’t mean a thing. Someone else’s spoon being used to serve the stewed apples doesn’t seem distasteful at all.

After lunch we washed knife, spoon, fork and mug and went back to the gymnasium where we had to strip to the waist and queue up for a medical inspection. Then we went to be fitted with clothes. We queued up outside a hut and went in ten at a time. We had to line up and take off coats and waistcoats. ATS girls fitted us with battledress blouses (they have to be loose fitting) and trousers, then the same outfit in dungarees.2 Three pairs of socks, two pairs of long pants or drawers, woollen as we later learned to call them, a long pullover, three shirts, greatcoat, hat, pair of boots, pair of brown plimsolls, pair of braces and a kit bag.

We signed for these and retired to the hut to put it all on. I hadn’t been so thoroughly dressed for some time. You wear a khaki shirt next to the skin, then a pullover, then the battle dress. Down below you have your long paints, narrow trousers, thick Army socks, and outsize Army boots.

But the thing that bothers you most is the side cap. You walk like a juggler every minute afraid it will fall off. It takes weeks to get the knack of wearing it at the proper angle: you have to ‘walk beside it’.

We went to tea, feeling considerably superior to anyone we passed not yet in uniform.

For tea we had bread, butter and a hunk of fish. No decadent dickering with plates however. There were no plates. I ate my hunk crushed into a monster sandwich.

After tea we made our beds and were free until 11.15 p.m. (but lights out by 10.15 p.m.).

I walked down round the town and went into the YMCA where there were half a dozen playing billiards. At the bar you could buy tea, coffee, cocoa, cigarettes, chocolates, sandwiches and buns. Prices negligible. The two women helpers were willing but vague; they couldn’t work the urn and they weren’t very strong on the prices. They would have been more at home in a cathedral-shadowed tea-shoppe. But then so would I.

I slept well. The bed was hard but tolerable. The lack of sheets didn’t bother me. I woke once or twice. The snoring was something awful, and one or two were talking in their sleep. ‘It’s raining, it’s raining,’ one of them said. Fortunately these manifestations died down after the first few nervous nights.

Easter Sunday

As I write we are hanging around waiting for a cobbler to come and stud our boots. Odd job for Easter Sunday morning.

Everyone is lying on his bed.

Two have been wrestling, but you don’t get much physical ebullience. So far most of them have spent most of the holiday in the hut on their beds. They can’t afford to do anything else, poor devils. Money is the big complaint. There is also a good deal of homesickness. Bred no doubt by lying about in bed.

This is the second weekend. Everything seems to have been going on for a long time. We are beginning to know where to go and what to do. Some have even learned to stand to attention when speaking to an NCO.

Everyone swears a lot in the Army. Just one word. I don’t quite know how not to say it. It starts with the sixth letter of the alphabet.

When we first came the old soldiers intensified their swearing to show us recruits that they were old soldiers. And after two days no one swore harder than the recruits. The non-stop use of this adjective definitely slowed up conversation.

(Self-Summary after Ten Days.)

I am much tidier, I put everything back and do everything up. I fold things, I shut doors, I look for the ashtray.

It’s funny to have to think about money. Not that I have ever had much to spare. But I always had plenty for the way I lived. Now I am trying to live the same way in my spare time without the same money. Trying to fill a quart pot with a half a pint. It involves those unpleasant division sums.

My income has been divided by eight, but so have my opportunities for spending it.3 I can live comfortably on what I have got providing I don’t go near London. And get keen on walking.

Odd how quickly I have got reconciled to relatively rough living and having no money. To me earned income was the main criterion of merit. I wonder how long this new Gandhi attitude will last. Most people have been even more philosophical. They hadn’t so much to lose but they lost more of what they had. It was pathetic to hear them say things like, ‘Well, no more Player’s Woodbines after today’.4

‘Fourth Week, Tuesday: Oh, Bad Shot’

My shooting form took a disastrous turn to the normal this morning. We went out to the small range for snap-shooting. You stand in a trench, crouch down to load the rifle, then the Sergeant shouts ‘Up’. You come up into the aim and fire before he says ‘Down’ a few seconds later.

I didn’t concentrate properly. I concentrated on concentrating instead of on shooting properly. I didn’t hit the target at all. Not once. My score was nothing. I was the only one who didn’t. When I’m bad I’m very bad.

Rumours all day about the Germans invading Holland, Denmark and Norway. But hardly the slightest interest in the hut. The morning papers had nothing and there aren’t many radios.

But after lunch – just now – Padbury came running in to say that Hitler had gone into Denmark and Holland and was at war with Norway.5 The atmosphere electrified for several minutes.

Comments: ‘It won’t be long now.’

‘I’m going on the bottle tonight.’

‘No more Maginot now; it’ll be you or him.’

‘I don’t bloody well care.’

‘I’ll buy a paper tonight to have a look.’

But a few minutes later it had completely dropped out of the conversation. There were nineteen in the room; four were reading papers, three were writing letters, two were singing ‘I’ll pray for you’, the rest were sleeping or cleaning their buttons.

‘Sixth Week, Monday: So Many Men’

I have just had a set-back. Tonight after remedial exercises in the new gymnasium there was a passing out test. Each man had to stand on his bare feet, full knees bend and up on the toes. I was quietly confident. I stood at the back cleaning my feet to help create a good impression. My turn came. Firmly, even proudly, I stood before the Sergeant.

‘What was your job in civvy street?’ he asked. My heart sank.6

‘I was a journalist, Sergeant.’

‘Did you flamp everywhere?’

I didn’t get this, but taking my cue from the sniggers around me, I sniggered too and said, ‘Well, yes and no.’

He put his pencil on the floor. ‘Try and pick it up as if you were a parrot,’ he said. I tried and failed.

‘You want to take care of your feet,’ he said ‘You haven’t used them enough. They aren’t very flat now, but they will be if you don’t work on them.’

Professor A.L. Rowse, the left-wing pillar whom I met at a Liberal Summer School five years ago, has been staying at the hotel in Dorchester over the weekend with a very pleasant history professor, now attached to the Chatham House foreign press investigators.7 He was saying that the Government are likely to embark on a big campaign for giving lectures to the troops. On the theory that the troops must be hungry for enlightenment. Personally I have noticed no evidence of hunger for higher learning.

The idea of these lectures would be to banish boredom. As far as I am concerned, they would definitely produce it. Especially when you think of the bores and charlatans who would inevitably work their way into such a scheme. I don’t think people would want to go to lectures, but once they got there, I think that most people would be interested. Just as they don’t want to to go to church or learn to fold blankets properly, but once they are marched along to it, they take an interest. Which immediately subsides on the command ‘Dismiss’.

After giving my advice on keeping the Army happy I had to fly back to the camp for our first night operations. The start was rather glamorous, with night falling fast and a whispered peptalk from the Corporal on the virtue and necessity of silence at night, for a careless laugh may mean ambush and death.

We marched off in platoons to a barrage of caustic comments from soldiers leaning on doors and out of windows. ‘Oh, you lucky people.’ ‘Have a nice time.’ ‘Does mother know you’ll be out late?’ ‘Look, dear, soldiers.’

On through the gates at the bottom of the hill and up through the half-made roads and huts of the new camp. A good many of the huts are completed. They are occupied by the last intake of recruits. They were singing to a banjo in one of them. We might have been back on the old plantation.

It’s an adventurous feeling to march along in silence at night. There’s a pleasant atmosphere of daring purpose about things. Heightened by the drum-like thud of hundreds of feet coming to the ground at once. We must have marched about a mile out over the common.

We were halted and the whole company was bunched together on ground sloping sharply down to the river and the railway. The Sergeant-Major cleared his throat and started as usual. ‘Now listen here a minute …’ when a train came along the line destroying the silence. In daytime no train would have stood a chance, but now the Sergeant-Major had to stop and wait until it passed. Amazing how much louder the same sound seems at night.

That was the point of our coming out. For a demonstration of how far a cigarette glows in the dark, how loud a laugh sounds, how far talking carries.

We all had to turn about while various numbers of men marched along the road at the top of the hill. We had to guess how many there were. It was difficult to hear them. For one thing there was rarely silence. A dog barked, some ducks quacked, a car stopped and started, and an engine shunted away on the other side of the town. Each sound in turn seemed to fill the world.

And our own people coughed, despite previous orders to stop it with a rag. The Company Sergeant-Major blew his whistle again, and somewhere in the distance men laughed to order. You could hear them telescopically well.

1 Anthony may have been slightly disingenuous in saying that the Corporal had recommended he take the corner bed; he was perfectly capable of grabbing himself the best spot. In his first letter home on 17 March 1940, he advised his brother Geoffrey, who was also just about to be conscripted, ‘I have a corner bed. (When you are led to the huts, Shubbles, get in front of the herd so you can get one too.)’ Shubbles was Geoffrey’s pet-name.

Anthony Cotterell to Graham and Mintie Cotterell, letter, 17 March 1940. Cotterell family archives.

2 ATS – Auxiliary Territorial Service, the women’s branch of the Army.

3 In his 17 March 1940 letter home to his parents, Anthony told them after making some comments on Army food, ‘Fortunately there are plenty of places to eat out in Dorchester. I am writing this at the place where I had lunch. A good lunch, the bill for two with half a bottle of wine being about ten shillings. Ten shillings being easily one week’s pay. (The other 4s are saved for you presumably to provide for the purchase of a wreath.)’ Anthony Cotterell to Graham and Mintie Cotterell, letter, 17 March 1940.

4 Player’s Woodbines – cigarettes.