Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

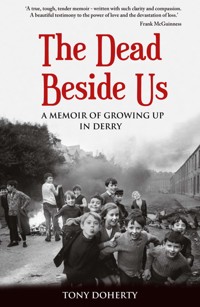

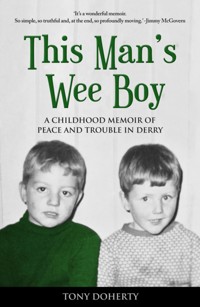

A uniquely-crafted memoir of the author's early childhood (1967–1972), the third oldest in a working-class Catholic family from the Brandywell in Derry. Written with the authentic voice of a child, this snapshot of his young life unfolds in a series of stories evoking the innocence of childhood, family dynamics and tensions, street friendships and characters, the onset of civil strife, and a family protecting itself from conflict, with CS gas coming in through the door and tracer bullets flying past the windows. The book centres on Tony's father, Patrick – a legend in his son's eyes and a man who struggles to raise a family through bitter years of economic inactivity. It beautifully and movingly portrays the relationship between Tony and the father he adores, yet slightly fears, as events, both within the family and on the streets, unfold and fuse together. The burgeoning chaos of conflict finds its way into his life through the death of a friend under an army truck and more horrifically, directly into the Doherty household. Described as 'a treasure', it draws the reader into a child's world, his innocent view of the harsh reality of life and the horrifying events unfolding around him. It has bags of humour and paints a picture of a lost world of children running wild in play, unsupervised by or worried over by adults. The book is also very moving, to the point of provoking tears at the end.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 313

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Tony Doherty, 2016

ISBN: 978 1 78117 458 6

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 459 3

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 460 9

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

To the memory of young Damien Harkin

Contents

Acknowledgements

1 Moore Street, 1967–68

2 Patsy, Eileen and Family

3 Moore Street Downfall

4 An Army Sangar on Hamilton Street

5 Tracers

6 The Folded Newspaper

7 Elvis

8 The Rickety Wheel

9 The Ray Gun

10 This Man’s Wee Boy

Glossary

Endnotes

About the Author

About the Publisher

Acknowledgements

There are a number of people who deserve thanks and credit. First, my wife Stephanie, for her support and patience, but especially for her belief in what I had set out to do; my mother Eileen, who, in the months before she died in August 2014, largely unknown to her, provided me with the rich pickings of our family history from her own memory bank; my big sister Karen, my wee brother Paul and my Uncle Eugene, who helped me bring our households in Moore Street and Hamilton Street back to life; my Aunt Maureen, for helping me out with the McFredericks; Dave Duggan, for telling me what to write about and how to do it; Lily (née Lily White) and Eddie Harkin, for allowing me to write about their son, Damien; Seán McLaughlin of the Derry Journal, for publishing ‘The Folded Newspaper’; Rónán McConnell of Derry City and Strabane District Council, for sourcing the Ordnance Survey map; Mickey Dobbins, Amanda Doherty and Julieann Campbell, for their prompt and honest feedback and encouragement; Minty Thompson, the oracle of every seed, breed and generation in the Brandywell; both Conal McFeely of Creggan Enterprises and the Trustees of the Bloody Sunday Trust, for helping me; Felicity McCaul, the godmother of The Literary Ladies, including Freya and Lynne; and Averill Buchanan for her skilful editing and her insightful feedback and guidance. Finally, thanks to my kitchen table and the two red robins, Maureen and Patrick, who came to my doorstep in the early spring and summer mornings. Maureen was there for a nosey and Patrick to practise his cursing.

Tony Doherty

1 Moore Street, 1967–68

My father (‘me da’) was at the open front door, standing between me and the sunny street. He was smoking and he looked up and down the street while I stood behind him in the darkened hall with my homemade drum hanging from a cord around my neck. Earlier he had made holes in the sides of a square biscuit tin with a screwdriver to knot the cord through. I had a wooden stick in each hand.

The marching band was forming under the sun in the middle of the street, halfway between our house and McKinneys’ across from us, mostly boys with one girl. Our instruments were sweet tins and biscuit tins; one had a family-size Heinz Beans tin. Some, like me, had their drums hanging around their necks; others just carried the tins in their hands. Our drumsticks were the kindling sticks used for lighting the fire in the house. The band gathered in the street, banging, clanging, clunking, raring to go.

As me da stood in the doorway the sound of a car could be heard coming to a quick stop at the bottom of the street.

‘What are these cowboys at now?’ said me da out loud to no one in particular. He stood down from the front step onto the street and I squeezed past him to join the band. At the bottom of the street two policemen got out of their car and one took a football from three older boys who had been playing there.

‘Hi!’ called me da, slowly making his way towards them. He had his beige shirtsleeves turned up as usual. ‘Hi! What the hell are yous boys at there wi’ them fellas?’ He stopped about twenty yards away from them and then began walking towards them again more slowly.

The dark-uniformed policemen looked unsure of themselves as he approached. The marching band stopped drumming. There was complete silence in the terraced street.

‘The days of yous boys messing wains about are over. Give them back their ball and get the fuck from this street!’ Me da was desperate with his temper when he started.

The policemen looked even more uncomfortable. The lanky one whispered something to the one with the ball in his hands, who promptly threw the ball back to the teenagers. None of them said anything.

Me da lowered his voice but you could hear him say, almost in a whisper, ‘Now fuck off into your fancy car and get the fuck out and don’t come back here messin’ people about.’ He pointed with his thumb towards the end of the road as he spoke each word.

The two policemen did exactly as they were told and drove off up the Foyle Road in the direction of Killea. Still puffing on his Park Drive fag, me da turned around with a broad grin on his face and walked slowly back towards the house. The teenagers went back to playing football.

Off the band went in single file up Moore Street. Me, our Patrick and Paul, Ernie Thompson, Dooter and Jacqueline McKinney and their dog Dandy – Dandy McKinney, one of the family. We all wore shorts and stripy t-shirts, and our plastic sandals of blue, brown and red made a sharp split-splat sound on the hard, dusty ground as we marched. I was at the back and Dooter walked in front of me. He wore red rubber boots that were too big for him so he flip-flopped about and staggered a bit as he walked.

The short-back-and-sides heads with wing-nutted ears bobbed in and out of the line in front of me as we walked in formation, banging the drums with our wooden sticks and making a noise that bore no relationship to the tunes we thought we were playing: ‘We all live in a yella submarine, a yella submarine, a yella submarine.’ Clunk, clunk, bang, bang – clunk, bang, clunk, bang.

As it was a sunny day some of the houses had their front doors open; there were prams outside with babies in them taking in the sun and fresh air. We passed Wee Mary’s house on the left near the top. Wee Mary would invite us in now and again. She lived on her own with her cats and didn’t say a lot. She just pointed and gestured and said some words now and again. Wee Mary Fleabag, some in the street called her.

On the other side, Barry McCool had Peggy the horse out of the stable and was brushing down her snow-white coat in the sun at the bottom of the steep bankin’. Barry smiled at us as we passed his stable. So did Peggy the horse.

At the top of Moore Street you come to waste ground. You turn right to go up the steep bankin’ or left to go down towards Hamilton Street, where you come out between the two gable-ends. Down we went: ‘Here we come, walking down the street.’ Clunk, clunk, bang, bang – clunk, bang, clunk, bang.

As we reached Hamilton Street we swung left and walked Indian file past Chesty Crossan, who was sitting on his kitchen chair in the shade in front of his cottage in his white string vest. He smiled as we passed, battering our drums and chanting the lines from The Monkees that we knew and humming the ones we didn’t.

‘Hello, Chesty!’ called our Paul.

‘Hello, wee Doherty!’ Chesty called back with a laugh.

Hamilton Street was longer than Moore Street, bending gradually almost out of sight towards Quarry Street, Lecky Road and the Bogside, which was out of bounds for us. The houses were all painted dull or pastel shades, with the odd splash of red or yellow on the windowsills to brighten them in the sunshine. The Barbours were playing tig in front of their house. As we passed, Johnny Barbour abandoned the game and took up position behind me. He had no drum, but he walked in formation with the marching band and sang what he knew.

We passed McLaughlin’s shop, with its grey walls and darkened insides, and then the Silver Dog bar near the corner. On the wooden bench outside a solitary, old, flat-capped man was sitting with a glass of stout in his hand. He smiled, raised his glass and said, ‘Good on yis boys’, as we passed by. As we reached the end of Hamilton Street and turned left onto Foyle Road, our Patrick said, ‘Get on the pad’, and led us towards the footpath. Foyle Road was busier than Hamilton Street. This was the bottom of Bishop Street, where the Morrisons and Thompsons lived. They weren’t part of the hated Bishie Gang because they lived at the bottom of Bishop Street, just around the corner from us. The real Bishie Gang all lived further up Bishop Street, out of view from our street. Kevin Morrison joined our band. He had no drum either but fell in behind Johnny Barbour as we made our way towards the corner of Moore Street again.

Mrs Thompson was out in her apron brushing the dirt and dust off her step. Her black hair was up in a bun on top of her head. She smiled as we passed and rested on her brush for a moment watching us make another go of ‘The Yellow Submarine’. She was Ernie’s ma.

The teenagers were still at the corner playing football and made way for us to get back to where we started. At that moment, a small blue van pulled into Moore Street just in front of us and stopped. The door opened and the Fishman got out. He had jet-black curly hair like me da’s and wore blue overalls.

‘Fresh herrin’!’ he shouted. ‘Fresh herrin’!’

The band stopped to watch. He opened the back doors of the van to reveal fresh fish packed in boxes. We could smell it from where we were standing. Women came out of their houses with coloured scarves on their heads. Paddy Stewart came out of ours with his flat cap on his head. The women paid their money and got their fresh herring wrapped in newspaper, chatted for a few minutes and went back indoors again. The Fishman closed the back doors, got back into the van and drove off down the lane to Hamilton Street. The band started up again and hurried down the lane after him, calling ‘Fresh herrin’! Fresh herrin’!’ at the tops of our voices and beating our drums ferociously. Dooter fell over in his red floppy boots and he and his drum clattered to the ground. Up he got, brushed the dust off his bare legs, and on we went. In Hamilton Street more women came out with coloured scarves on their heads, bought their fish, chatted and went back in again. The wee blue van drove off towards Anne Street below where me granny and granda Doherty lived in the prefabs.

The marching band broke up in Hamilton Street, where we joined the Barbours playing tig, running away from whoever was ‘it’, and declaring ‘parley’ by touching a lamp post with both hands so you couldn’t be caught and you could get your breath back. After the tig we sat down in the sun on the kerb opposite Chesty, still sitting in his kitchen chair at his front door.

I spied a patch of dull-pink chewing gum stuck to the road and poked at it with an ice-pop stick to see if it would move. Softened by the heat, it came away easily in pinky-white strings.

‘Hi, I got chewin’ gum! Look!’ I shouted.

‘What is it?’ asked Johnny Barbour.

‘It’s a Bubbly,’ I said, rolling it in my fingers. I kissed it up to God and put it in my mouth. There was still a bit of flavour off it, as well as a few pieces of grit, which I picked out in a pincer movement with my tongue and fingers.

‘Gis that ice-pop stick,’ said Johnny.

I threw him the ice-pop stick and he poked at a piece of dull-white chewing gum near his feet. It came up in strings too. The sun was a blessing for chewing gum. He rolled it in his fingers, kissed it and held it up to the sky.

‘I kiss this up to God,’ he said and promptly stuck it in his mouth.

‘What kind did you get, Johnny?’ I asked.

‘Beechnut,’ he said with a smile, crunching on a bit of grit, as I had.

‘It’s okay when you kiss it up to God, isn’t it?’ said our Paul, sitting down beside Johnny.

‘Aye, it is. As long as you kiss it up to God you won’t get poisoned,’ I said and watched our Paul poke another dull-pink Bubbly with the stick.

* * *

It was our first day at school. The classroom at Long Tower Primary School had erupted with four-year-olds crying for their mammies. Mrs Radcliffe was being stern with some of the mothers who were in the classroom. They had to leave. They were only making the children worse. Almost all of the thirty boys were crying like babies and I wondered what they were crying about. I was the only boy in the class not crying. It took a long time to get the mammies out the door. They stood outside looking in through the glass at all the wains crying. Then some of the mammies started to cry. Mrs Radcliffe went out to them, closing the door behind her. Eventually they dried their eyes and left. Mrs Radcliffe was always stern. When school finished later that day they were all back, crying again in the yard. The mammies had their boys by the hand or were hugging them.

Only a few boys cried on the second day, but one of them cacked himself in the classroom. Mrs Radcliffe was purple-faced. She took him out to the toilet. When they came back he was wearing someone else’s trousers. We all got a small bottle of cold milk in the morning. Some boys didn’t drink their milk but Mrs Radcliffe said you had to, to make your bones and teeth strong. They only sipped it. I drank the whole bottle as I wanted to have strong bones and teeth. I had toast wrapped in bread-paper for lunch. The two slices of cold toast were really nice because the butter had caramelised with the burnt bits. We got hot tea with sugar at lunchtime. Mrs Radcliffe poured it for us from a giant silver teapot into cups and small milk bottles.

I went home with our Patrick and Karen. Karen was a big girl in Primary Three in the Long Tower Girls’ School.

On the way home one day our Patrick said to me, ‘You’re deef.’

I said, ‘What?’ and he said, ‘I said, “You’re deef.”’

‘What d’ye mean, deef?’ I asked.

‘Me ma said to Paddy Stewart the other day that she thought you couldn’t hear right, and Paddy said that you might be a bit deef all right,’ he said.

‘But I’m not deef. Sure I can hear ye talkin’!’ I said, feeling a bit hard done by.

‘Well, that’s what they said. You’re deef and that’s it!’

‘Naw, I’m not deef! I’m not, aren’t I not, Karen?’ I asked, alarmed and looking for another opinion.

‘Naw you’re not. Patrick, stop you narking him,’ she replied.

‘I’m only tellin’ yis what they said. It was Paddy Stewart that said you’re deef,’ said Patrick.

‘Well, give over about it now,’ said Karen and we walked home in silence.

A day or two later me ma called into the school to get me out early. She was standing in the corridor when Mrs Radcliffe said that I had to go. We walked from the Long Tower School towards Abercorn Road where Riverview House was. As we walked me ma said she had to get an hour off work in the factory to take me to get a hearing test.

‘I’m not deef, Ma, amn’t I not?’ I asked, looking up to her face to see her reaction.

‘Och naw, son,’ she said, with an anxious smile back at me. ‘Everybody gits an ear test when they’re young.’

‘Everybody in the class?’ I asked.

‘Aye, you’re the first. Aren’t you the lucky wan?’

When we got to Riverview House we were taken by a smiling, blue-uniformed nurse into a cream-painted room with two wooden chairs and a wooden table with a wooden mallet on it and a pair of black metal earphones wired into a grey metal box on the wall above the table. The nurse explained that I was to put the earphones on my head, she would go out of the room and that I was to tap the table with the wooden mallet after I heard a beep on the earphones. Me ma sat down at the table opposite a large, square window looking into another room, behind which the nurse would sit down. I was to sit facing away from the window. The nurse placed the earphones over my head, covering both ears. I couldn’t hear a thing from this point on and wondered was I supposed to be hearing beeps or was I really going deef. I had the mallet in a death-grip, and had heard nothing yet from the earphones. I waited … and waited a few seconds more …

I heard a very faint beep. A weak one but I definitely heard it! I raised the mallet and brought it down hard on the table with all the strength of a boy worried about going deef. Bang! Me ma, who had been looking in at the nurse and not at me, screamed ‘Jesus Christ!’ at the top of her voice, jumped up from her chair, her handbag fell off her knees onto the floor and all her belongings fell across the floor. Papers and lipstick everywhere. The nurse rushed in from the windowed room next door and said, ‘Are you okay, Mrs Doherty?’ I could only hear the talk in muffles. Me ma sat back down on her wooden chair, put her hands over her face, and her shoulders started heaving. I thought she was crying into her hands but then I heard the laughs of her and, when she took her hands away, her eyes ran black with make-up.

‘Jesus, Tony Doherty!’ she said, still laughing. ‘You’re goney bring on a heart attack!’ The nurse and me ma got down on their hunkers to lift all me ma’s things from the floor. Me ma then placed the handbag squarely on the table.

‘I know, Tony,’ the nurse said, smiling and patting my hand after she lifted the earphones from my head. ‘Just hit the table a wee tap so I can see your hand moving through the window.’ She placed the earphones over my ears again and returned to the other room. My knuckled grip on the mallet remained strong, despite the nurse’s advice. I had the earphones on and could hear nothing. So I waited … me ma, her still giggling and looking at me this time, put her hands up to her ears. I waited …

I heard another very weak beep. Weaker than the first one but definitely a beep! Again, I brought the mallet down hard on the wooden table with all my strength. Bang! Me ma, who had been watching me this time, put her hands round to cover her open mouth as she looked, wide-eyed, in through the window at the nurse. The nurse came in again from the other room, gently lifted the black earphones off my head and said, ‘Mrs Doherty, there’s not a thing wrong with this boy’s ears, but could you take him out of here before he wrecks the place!’ My grip on the mallet released at the news and I put my hands down by my sides.

‘Oh dear, nurse, I’m really mortified,’ said me ma, who was still wiping the black make-up from her eyes with a hankie.

‘That’s okay, Mrs Doherty. He’s a wile man, that ’un!’ said the nurse, smiling back at us.

‘Och, I know. He’d get ye hung!’ laughed me ma as we went out through the large wooden doors.

‘I’m not deef, Ma. Aren’t I not?’ I asked her again as we climbed the stone steps up to Abercorn Park.

‘Naw, you’re not at all, son. You’re just in a world of your own sometimes.’

I wondered what she meant as we passed the swings and slides towards home.

I’m not deef and that’s the main thing! I thought to myself and couldn’t wait to get home to tell our Patrick.

* * *

Paul started Primary One in September 1968. The four of us walked home together down Bishop Street. There were Daz washing powder promotion coupons posted in the doors the whole way down the street. We pulled them out of the flaps. They were currency in the shop. We cut in from Bishop Street, dandered around the base of the bankin’ and went in through the back gate to the whitewashed yard with the toilet. It always smelled of a mixture of farts and old damp newspaper.

Paddy Stewart – Uncle Paddy – stood proudly in our kitchen as we filed in the door. ‘Your dinner’s ready,’ he said.

The dinner was in bowls keeping warm on top of the range. There was a light skin on the beans, which made them even nicer. Beans, sausages and mashed spuds with butter. Paddy wasn’t really our uncle but he came with the house. He lifted the bowls with a towel over to the drop-leaf table in the scullery and salted the food for us. We tore into it with spoons.

‘Was school good the day, Paul?’ he asked. Paul was his favourite, you could tell.

‘We got all the Daz coupons coming down Bishop Street,’ announced Paul.

‘That’s great son, that ye got the coupons.’

Paddy was sitting drinking a cup of tea on the chaise longue while we ate. He was a lovable man with his round belly and red nose.

‘Paddy, me da said that ye played for Derry. Did ye?’ I asked from the table.

‘Oh aye, I did surely. Me and me brother Gerry. Played in the Brandywell, and up and down the country. That was years ago. I wouldn’t be fit now to kick football, boys-a-boys,’ Paddy laughed.

When we were playing out the back lane we used to pee ourselves laughing when Paddy went to the toilet in the yard. ‘Wait d’ye hear the blatters of this. Paddy’s in the shite house,’ we’d whisper to each other. And sure enough, Paddy would oblige, as loud and proud a blatter of farts that you ever heard.

* * *

Me ma worked in a shirt factory. One morning I saw her from our doorstep getting on a bus on the Foyle Road at the bottom of Moore Street. I never knew she got a bus to work and was excited by this. I called out to her but she didn’t hear me. I ran down Moore Street, waving, until I reached the bottom. All the women in the bus were laughing and waving back. I saw me ma walking up the bus and stooping down to look at the waving boy. She waved back and laughed. I didn’t know why they were laughing.

Our house was really dootsy and old-fashioned. The only new things were the black plastic settee and matching chairs in the front room. The cushions were a fiery orange. We had square-patterned oilcloth all over the downstairs floor and on the stairs themselves. It was very worn in the hall. You could see the black stuff coming through where the pattern had worn away. There were two blue-and-white dogs that sat high up on the wooden mantelpiece, one on either side of an old brown clock with a yellowed face. We were No. 6 Moore Street, the house with the dull-green door and the heavy brass knocker. Other knockers on the doors in Moore Street were shiny. Ours wasn’t.

The McKinneys lived across the street. They had a van because their da, Cecil, had greyhounds. He was a doggyman. Cecil and the McKinneys’ Uncle Davy kept the dogs in sheds up the bankin’ up near the College. We were allowed to walk the dogs out the Line with Terry, who was older by two or three years and knew everything. The Line was a disused railway track which ran the full length of our side of the River Foyle. Sometimes we were allowed to go to the dog races at Lifford Stadium. We’d travel in the back of the van with the dogs. We got chips and coke and learned how to gamble. You got a coloured ticket when you bet. My favourite dog was DC Wonder. DC stood for Derry City. She was a big, fawn dog. Nearly all Cecil’s dogs were called something or other Wonder, such as Joan’s Wonder, The Third Wonder and The Eleventh Wonder, although one was called Teresa’s Pride after Dooter’s wee sister and Cecil and Maisie’s youngest daughter.

Dooter was called Dooter because, when he was a toddler, he couldn’t say his name right. His real name was Christopher but he could only say something like Dooter and it stuck, though his ma and da still called him Christopher.

The McKinneys were the same ages as us. Our Karen was the same age as Terry McKinney; our Patrick, named after me da, was the same age as Michael McKinney; I was the same age as Jacqueline McKinney who, it was rumoured, was my girlfriend; and our Paul was the same age as Dooter. After Paul the Dohertys stopped for a while, but the McKinneys kept on coming – there were Teresa and Don. They weren’t the same age as anyone so didn’t really count. They had Dandy the dog, though. She did count. We had no dog. We used to sing:

Doherty’s sausages bad for your heart, the more you eat the more you fart!

Doherty’s sausages bad for your heart, the more you eat the more you fart!

McKinney’s tea, makes your granny pee!

McKinney’s tea, makes your granny pee!

There was no McKinney’s tea. But there were Doherty’s sausages.

* * *

It was my fifth birthday. My birthday was exactly a week after Christmas Day – on 1 January. (I was born just after midnight, me ma said, in the front bedroom of me granny Quigley’s house in Central Drive during a terrible storm.) There was no money to do anything special for my birthday; they had spent it all at Christmas. But Karen was sent to the shop for a Swiss Roll and a bottle of Cloudy Lime. The Cloudy Lime was poured into cups and me ma stuck five candles in the Swiss Roll and lit them.

‘Blow them out and make a wish,’ she said as we sat around the coffee table in the front room on New Year’s Day.

I did. I wished for something for my birthday.

‘We’ll get you something when we get paid,’ said me ma, looking at me da. ‘Isn’t that right, Paddy?’

‘It is surely, Eileen,’ he said with a smile.

Me da usually got paid on a Friday. I think me ma did as well. On payday we got our own pay from me da when he got home from work. Me ma didn’t pay us. We’d wait for him coming across the waste ground at the top of Moore Street and run to meet him to be lifted up and get our pay when we reached the house. Sometimes he’d be late so we just played at the corner and watched out for him. If he was late you could smell the beer off him when he lifted you. He’d rub his stubbly face roughly into our necks when he had the drink in him. Once he scratched Karen on the face, he rubbed that hard. Sometimes he’d pull bars of chocolate from his work-coat pockets as we walked back towards the house – usually Marathons and Bar Sixes. Marathons made you run faster; it said so on TV. Our pay was handed over at the table – sixpence for Karen and Patrick, and fourpence for me and Paul.

We used to go and make secrets in the bankin’. Secrets could be holy medals or coloured milk bottle tops or something cut from a magazine. It didn’t matter so long as it was shiny when placed against the soil. Then it was covered over with coloured glass, usually the bottom of a green bottle. The glass changed the colour of the secret. This was the secret. We went back the next day to see if the secrets were still there. They were. They looked peaceful under the green glass. We covered them and left them there for another day. You could see other people’s secrets. No one kept them secret.

I had my own secret. I saved my pay in a hole in the bankin’ for a number of weeks. I didn’t save for any particular reason; I just saved. I didn’t tell anyone. I’d just sneak off after we got our pay at the table and go round to the base of the bankin’, remove the sod and stash the four big copper pennies. I covered the dull pennies over with the bottom of a Mundies wine bottle with a hollow in it. I did it for about three weeks. I had twelve large pennies to my name, blew it all on sweets and chocolate in Melaugh’s shop on Hamilton Street and bought everyone in the marching band Dainties, Bubblys and Chocolate Logs. We shared a big glass bottle of Black Cat Cola between eight of us. Black Cat Cola had a cartoon picture of a smiling black cat on the label. Black Cat Cola was the real deal.

The paydays came and went. Each school day I’d get up to see if my birthday wish had come true. Each day as I came downstairs there’d be nothing in the hall or the scullery or front room. But I kept true to my wish. One day, as we awoke for school and came downstairs, there was a big red toy bus with yellow seats parked in the hall. I ran down the stairs in delight that at last my wish had come true.

‘That’s not yours, Tony,’ said me da, not realising. ‘It’s Paul’s birthday the day, so it’s his.’

I was devastated. This was my first big let down with my parents.

Paul came running downstairs.

‘Thanks, Mammy and Daddy. This is class, hi!’ he said, as he got on the bus and pushed himself up and down the hall.

I started to cry in my arms against the wall in the scullery and me ma shouted at me to stop being so selfish. ‘It’s your brother’s birthday, not yours.’

A few nights later the red toy bus was parked outside our house.

‘Dooter, jump you on and I’ll push ye,’ I said and Dooter jumped on.

I pushed him around the back of Moore Street below the bankin’ where we came to a stop in the muck.

‘Hi, Dooter,’ I said, ‘I’ll give you half my pay this week if you do me a favour.’

‘What?’

‘Lift that boulder there and hit the bus wi’ it,’ I said.

Without any further persuasion from me he lifted the heavy round boulder and brought it down with a crash on top of the bus. Its red roof split in two and a wee yellow seat scooted out onto the grass.

‘Do it again, Dooter,’ I said, and he did it again.

More yellow seats shot out of the bus. Then I lifted the boulder and smashed it down hard. The bus broke in two, with yellow and red pieces of plastic scattering on the green grass. It didn’t look like a bus when we left.

Away we ran back round to our street. Me da and Paul were out at the front door.

‘Did ye see our Paul’s bus?’ me da asked.

Paul was crying. Dooter took off in his red waterboots and ran into his house and closed the door without looking back. I was on my own.

‘What’s wrong wi’ him?’ he said.

I didn’t answer.

‘What are yous boys up to?’

I said nothing.

But he knew. ‘Did you take his bus, boy?’

I didn’t answer.

‘Take me around the corner!’ he demanded angrily.

I was hammered and I knew it.

When we got round the corner past Barry McCool’s stables to the bankin’ it was all still there. It hadn’t disappeared. Paul started howling the way Dandy McKinney howls at the music from the Poke Van.

‘It was Dooter, Daddy. It wasn’t me. I tried to stop him but he lifted that boulder there and just smashed it,’ I said.

He didn’t believe me. Paul was sent howling round to the house to get a box. He was still howling when he came back with the box. The tears and snotters were blinding his eyes, which looked at me and at the scene before him in disbelief at what I’d done.

‘It’s all right, Paul. We’ll get you another bus,’ said me da to get him to stop.

It didn’t work. He howled on.

‘You.’ Me da looked straight at me. ‘Put all the pieces into the box.’

I got down on my hunkers and started collecting all the broken bits of red and yellow plastic from the mucky ground.

‘Right, carry it back to the house. Now.’

As I turned with the box in my arms he gave me a right steever with his boot up the backside, shoving me on a few extra yards with the force. I started to cry. The box wasn’t heavy.

‘You’re in bother, boy,’ was all he said from behind me as we walked. I knew he meant it.

When we got back to the house I put the box down on the scullery floor and then I was sent upstairs to put on my Sunday clothes. My Sunday coat was waiting for me over the chaise longue when I came down. It was brown check with chocolate brown buttons. They looked too much like chocolate to be buttons. There was a small, dull-brown attaché case with a brown leather and metal handle sitting in the hall, exactly where the bus was parked on its first day. Everyone was gathered in the scullery – Ma, Da, Paddy Stewart, Karen, Patrick and Paul. The howling had stopped and Paul was wiping his snotters into me ma. The box of broken plastic was still on the floor where I’d left it. Everyone stood around it.

‘You’re coming wi’ me, boy,’ me da said, picking up the case as we went out the door.

We walked side by side down to the bottom of Moore Street. I looked around before turning the corner and saw that they were all standing outside the house, watching. The leaving party. Our Paul was smirking at me.

‘You’re goin’ to Termonbacca, boy,’ said me da as we walked down the street. ‘That was a terrible thing you done on your brother.’

Termonbacca was where Gerry Goodman lived. Gerry Goodman was in our class in school. He had no parents so he lived in Termonbacca with the nuns. He was very happy; he smiled a lot. He always wore grey long shorts and brown boots with grey socks and a navy blue blazer. All the home boys at the Long Tower wore grey trousers that went down to the knee. Gerry Goodman was going to be my best friend. I wondered what wearing long short trousers felt like.

We turned the corner onto Foyle Road and could see the lights on the hill where Termonbacca sits. Me da walked without a word and at a fast pace, but I kept up with him. I didn’t know what to say so I stayed silent. Anyway he’d made his mind up, by the looks of him. He carried the attaché case. I held his hand. It was freezing. I was feeling the cold. When we reached the corner of Lone Moor Road he stopped suddenly.

‘Do you want to go and live up the Coach Road with the Home Boys, Tony?’ he asked.

The Coach Road! The Coach Road was so named because the Headless Coachman rode his black, horse-driven coach up and down that road in the dead of night and kidnapped children and took them away for ever.

‘No, Daddy,’ I said truthfully. ‘I’m really sorry,’ I added; that wasn’t so truthful. ‘I don’t want to go to up the Coach Road to the Home.’ I started crying. I had visions of lying in bed in the Home hearing the Headless Coachman on the road outside cracking his whip and screaming at the kidnapped wains in the coach to be quiet.

‘Sorry for what?’ me da asked.

‘Sorry for smashing Paul’s bus,’ I said, lying through tears this time. ‘I’ll make up for it. I’ll give him my pay for four weeks.’

‘Right, I’ll give you one more chance. Another stunt like that and you’re for up the Coach Road. Okay?’

‘All right, Daddy. I won’t do it again. I’m really sorry.’

I wasn’t.

We turned around and headed back towards Moore Street. Dooter was out playing in the street and ran in again when he saw us coming round the corner. When we reached the house everyone was in the scullery around the heat from the range. I was sent to bed after saying sorry to Paul and promising to pay him four weeks in a row.

That night I pictured myself being lowered into a grave and looking up to see me ma and da crying their eyes out as they looked down at me disappearing. It’d serve them right, I thought as I drifted off to sleep on my own.

* * *