Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

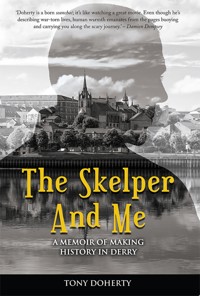

In this sequel to the hugely-popular This Man's Wee Boy, young Tony Doherty struggles to come to terms with the murder of his father, Paddy, on Bloody Sunday and the impact it has on his mother, Eileen, and his brothers and sisters. At nine years old, he knows a terrible wrong has been committed against his family but lacks the understanding or the means to do anything about it – yet. For his fractured family, life goes on, with Tony determined to preserve the memory of his father and the bond they shared, even as he becomes increasingly immersed in the violent conflict raging on Derry's streets. As the 1970s unfold his father's absence remains the backdrop to the teenage Tony's newfound friendships and relationships, an ever-present ache amidst the craic and excitement of Sunday dances, first kisses and a trip to Butlins. Then, at seventeen, Tony decides it's time to join the fight.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 402

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

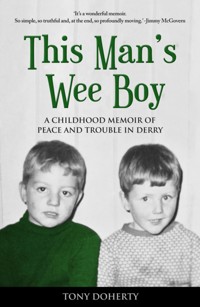

Praise for This Man’s Wee Boy

It’s a wonderful memoir. So simple, so truthful and, at the end, so profoundly moving.

Jimmy McGovern

I was so impressed with this book, and so moved, because it brings home, like no other writing ever has, just how damaging and toxic living in the centre of violence day to day must have been. That voice of innocence never slipped. I am in awe of Tony Doherty.

Sue Leonard, Irish Examiner

The strength of these accounts lies in the authenticity of their nine-year-old narrator, whose perceptions – unclouded by adult interpretation or reflection – retain all the innocence and excitement of a child experiencing something for the first time.

The Irish Times

As we have moved past conflict here there are times when we may appear to take some of what has been achieved politically for granted. This book works to remind us of just how far we have come and how precious peace is. Read it to remember and to learn.

John Peto, Culture NI

If the city of Derry ever falls to ruin you could probably recreate its essence from the memory of Tony Doherty, who knows its streets, its characters and its vernacular the way he knows himself. In his pitch perfect new memoir he has distilled his childhood memories to their rich essence. … There is so much love in this book that it often arrests you. The way people speak, the spirit of fun they express and the unforgettable words they express it in are a testament to his deep affection.

Cahir O’Doherty, IrishCentral.com

For Eddie O’Donnell

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Tony Doherty, 2017

ISBN: 978 1 78117 512 5

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 513 2

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 514 9

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Acknowledgements

At home I am extremely grateful to my wife, Stephanie, for supporting me throughout the writing process and delivering several sharp critiques of the later chapters. Also my son, Rossa, for interrupting his busy social media schedule to read over several chapters and telling me that I wasn’t such a goat after all.

On the wider family front, thanks to Uncles Eugene and Gerard for helping me restore sensible order to events after my father’s death and to my wee brother Paul for taking the rubbish out to the bin.

Thanks to Christopher (Dooter) McKinney and Brian McCool, for helping me clarify several snippets of memory of my Brandywell days. I am really glad that I spent time with my old friend Benny McLaughlin, who was of enormous help keeping me straight about our shared Galliagh and Shantallow days in the 1970s. Thanks also to Kevin (Boiler) Boyle, his brother Bobby, and Brenda Cooley (now Kearney) for a variety of memory jogs and for teaching me to jive (Brenda, I mean). I am very grateful to Tommy Carlin for his support and input, albeit regarding much more serious matters.

On the production side of things I am indebted to Mickey Dobbins for his enthusiasm and encouragement during our many tours to and from Belfast. Also Amanda Doherty and Catherine Murphy for their help and feedback; and Dave Duggan for providing me with the overview of my memoir without reading a word! I am especially grateful to Freya McClements for her valuable and insightful assistance in too many ways to mention.

Readers, please note that Patrick Brown (now deceased) and Paddy Brown are two different people.

I would like to thank Christine Spengler for allowing me to use her brilliant photograph on the cover.

Finally, I apologise to all those whose names I have changed or simply left out of the later chapters due to good sense and sensibility.

1 Hunger in the Heart

My earliest memory is of my granny’s house in Creggan. It was 1966, when I was three. The singer sang ‘What a Day for a Daydream’ on the transistor radio in the scullery, and me granny was standing at the table, the sleeves of her pale blue jumper rolled up, kneading dough with her floury fists. I stood in the doorway of the sitting room with a mixed-fruit jam piece in my hand as the sun shone through the large window, catching dust and fine fluff in its streaming rays.

I found myself once again standing in the sitting room of me granny’s house, after we buried me da on a cold, wet and windy February day in 1972. The house was choc-a-bloc. A huge fire roared in the hearth as the inviting aroma of homemade chicken soup struggled to win over the gloom and the less inviting smells of steaming hair, soggy shoes and damp clothing. We took turns heating up and drying off in front of the fire as me granny took charge in the scullery. She always made more than enough to feed everyone; her cooking pots were huge and she had enough bowls to feed an army. She’d arranged for Mr McLaughlin, the bread man, to deliver a full wooden tray of Hunter’s sliced pan loaves, which lay, neatly packed in their blue and yellow wrappers, on the floor beside the front door. It was a strange gathering, though, as me granny’s house was always a place for the craic, scone bread and feeling good, and now here we were not knowing what to do or say, feeling the loss of me da in the same room where he’d sung ‘The Black Velvet Band’ to me ma at the Christmas party only a few weeks ago.

When your da dies so suddenly, killed by a soldier’s bullet, it does things to your head and body that you can’t really work out. I felt a terrible hunger of a strange and different kind than I’d ever felt before. At least, I can only explain it as a hunger, but it could’ve been something else, as food didn’t seem to take it away. I could feel it right up to my throat. Food didn’t taste the same and I would still feel the strange hunger soon after eating. In the few days since me da was killed, over the wake and after the funeral, I felt this hunger. Something had changed in me as a nine-year-old, in both body and mind. The mysteries of how, why and where me da died were great unknowns to me that I couldn’t yet begin to explore. I didn’t even know the right questions or who to ask about it.

In hushed, mysterious tones, spoken as much with the eyes as the mouth, word went around the thawing-out gathering that Josie Brown had seen a rath of me da in St Mary’s Chapel.1 Josie was me granny’s friend who lived around the bend of the Cropie, across the street from No. 26 Central Drive. She always had a smiling, thoughtful face, her head shaking slightly when she spoke. It didn’t shake when she was quiet. She smoked, like almost all the older people, but she often kept her fag drooping at the corner of her mouth, gangster-like, allowing the smoke to crawl its way up the side of her face and out through her soft white curls, shrouding her head in a smoky mist.

Josie was special. She saw things differently from everyone else, me granny used to tell us. They held nights in each other’s houses so that Josie could read their tea leaves. She told me ma one such night, after reading her tea leaves, that she would wear two wedding rings.

Josie told whoever was gathered around the scullery table that she’d seen Patsy Doherty’s rath when she was in the queue for Holy Communion at Mass the previous day. She stood near the main door of the chapel at the end of the long queue and saw Patsy Doherty walking towards her with his hands clasped in front of him and his eyes towards the floor. When he reached Josie, he smiled and winked an eye at her as he passed by. When she looked around, he was nowhere to be seen. She said she nearly died with the shock of it.

Word of Josie’s meeting with me da’s rath spread throughout me granny’s packed house. It was Aunt Siobhán I heard it from, when she was telling someone else in the hall beside the sitting-room door. The news brought a strange comfort to me and I’m sure to the rest of us Doherty wains; it was as if he was still here with us and would look after us.

Me granny always served her chicken soup with a few boiled spuds, sitting like floury balls in the middle of the wide bowl. I sat with my sister Karen and brothers Patrick and Paul, lined up along the sofa with the steaming soup bowls on the low coffee table, and we bent forward as best we could to slurp the soup and dip the sliced pan bread into it. Others, including my Uncle Joe (about the same age as Karen) and Aunt Lorraine (three years younger than me), hunkered down on the floor and blew the hot steam from the soup to cool it down, dipping the bread into it and shaping their mouths to trap it before it came away, splashing its soggy weight back into the bowl. The large, metal-framed windows of the sitting room were steamed up, keeping the heavy, grey February day at bay for the time being. If me granda had been himself, he would have said, ‘It’s like a buckin’ Turkish bath in here’; but he didn’t.

***

With me da gone and in his grave, me ma’s head was elsewhere. Her face was pale and angst-ridden, her voice frail and distant. She was twenty-nine. She had six wains, the youngest only seven months old. Everything around us seemed different. The emptiness was everywhere and it was as if we all had to get to know one another all over again. Like strangers. There was always someone else around the house helping out, or just being there – my Aunts Siobhán (about seven years older than me) and Mary, or me Uncle Patsy and his wife Geraldine. Maisie McKinney from up the street came in very often and took us to her house for our tea while me ma rested in bed. We spent time, including a few nights, at me granny’s in Central Drive. Me and our Paul even stayed a night in Maisie’s, had our tea and toast for supper, and got packed into the bed ‘heads and thraws’ beside Dooter and Michael. It was strange falling asleep with someone’s smelly feet near your pillow, like the old days in Moore Street.

We stayed off school for a week after me da’s death. I’d never missed a single day of school before. At the end of Primary Four, Mrs Radcliffe had awarded me a KitKat for the achievement of never missing a day since I started in Primary One.

The following Monday morning, Patrick, Paul and me were sent back to Long Tower Primary School. For some reason we were allowed to go in late, and as we walked from the Bishop Street gate past the Primary One, Two and Three classrooms I realised that there wasn’t another boy to be seen outside. The yard was empty, cold and grey. They were all inside in the warm. We walked in silence through the chilly schoolyard and split up into our separate classrooms. Patrick was in Primary Six; I was in Primary Five; and Paul was in Primary Four. It felt odd that I was at school and when I got home afterwards me da wouldn’t be there.

The three of us walked home together in silence after school. We were watching TV when there was a noise at the front door and Patrick got up to see who it was. Our Uncle Michael was in the hall and he came through the door with a cardboard box in his arms. Uncle Michael was a tall, gangly teenager who always wore jeans and his hair was dark and styled like Rod Stewart’s – spiked at the front and long at the back. When he put the box down on the floor we could see a wee brown pup inside, lying on a bed of straw and newspaper. We had our own dog at last!

‘It’s a bitch,’ he declared.

Maisie McKinney came in shortly after and had her dog, Dandy McKinney, with her. Dandy sniffed around the cardboard box and nosed and licked our new pup, wagging her stubby, sandy-coloured tail.

‘She’s takin’ to the wee pup,’ said Maisie. ‘She loves pups.’

We all sat around the box on the floor while the pup slept on her straw and newspaper, and the older and wiser Dandy lay down beside it with her head between her front paws.

‘Now, make sure and train the wee pup,’ said Maisie. ‘You don’t want it cackin’ all over the house; and a dog has to know that it is a dog or it won’t know its place. Our Terry will give yis a hand. He’s great wi’ dogs.’

Me ma came in with Uncle Patsy and Aunt Geraldine. Geraldine was a small woman with short, dark, curly hair, horn-rimmed glasses and a slight country accent. She drove a car. She was the only woman I knew who drove a car. Uncle Patsy wasn’t that much taller than her. He had black hair and his shadowy face always looked like he needed a shave. They were nearly always together; you rarely saw one without the other.

‘We got a new wee pup, Ma!’ said our Paul.

Me ma came over to the box, sat down on the edge of the sofa and lifted the pup onto her lap. It opened its eyes for a second as it was moved, then settled back into the warmth and slept on.

‘Ach dear, look at the wee critter. What’ll we call it?’ she asked, smiling. Because the wee pup had a brown coat of hair we named her Brandy, after me ma’s favourite drink. Brandy Doherty, one of the family.

Patsy and Geraldine were in the scullery getting something ready for us to eat.

‘We got a couple of beef curries and rice from the new Chinese restaurant in Shipquay Street,’ said me ma. We’d never had curry before and could smell its strange aroma coming from the scullery table, where Patsy and Geraldine were dividing it out from tinfoil cartons onto plates. It smelled really different from anything we’d ever eaten.

‘I’d better get home and get a spud on for the dinner,’ said Maisie, and me ma walked her and Dandy out to the hall and closed the sitting-room door behind them. By the time she came back in we were sitting around the room eating our first Chinese beef curry. We got a cup of tea as well, which tasted strange along with the curry. Everything tasted strange to me anyway since me da died, so I wasn’t that put out.

‘I’m not really hungry,’ said me ma as she forked the curry around her plate.

‘I know, Eileen, but ye have to eat to keep your strength up,’ said Patsy, standing by the scullery door with his plate in his hand, looking concerned. Everyone agreed that the Chinese curry was delicious and we Dohertys all licked the curry sauce from the plates until they were clean.

‘We won’t have to wash the plates now, Patsy, look at the clean of mines!’ Paul said, holding up his white plate for everyone to see. Patsy laughed and said, ‘I know, Paul, but you’ll still have to wash it in the sink.’

Patsy and Geraldine gathered up the plates and forks while we drank our tea. Everyone agreed the tea tasted very strange because of the hot curry sauce, so most of it went cold in the cups. Patsy and Michael went into the scullery to wash the dishes.

‘He was tryin’ to reach his cousin’s flat in Joseph Place, ye know,’ said me ma, drifting her eyes towards the sitting-room window. It was now dark outside.

‘What, Eileen?’ said Geraldine, looking at us through her horn-rims. We were all listening. Brandy was sleeping in her cardboard box.

‘Paddy. I think he must’ve been trying to reach his cousin’s flat in Joseph Place. That’s where he was shot.’

‘D’ye think so, Eileen?’ asked Geraldine, looking around at us as we listened. This was the first time me ma had spoken about it since it happened.

‘We went out after dinner and left Karen to watch the three boys. We took Colleen and Glenn up to me ma’s in the pram and then went over to the shops for the march. We had great craic as we walked down Southway; people were calling to one another and all, but when the rioting started I turned round to see where he was. We got separated. Then I met me da and stayed wi’ him. That’s when the shooting started. He had to nearly drag me over the barricade because I couldn’t get over it myself.’ She smiled a soft smile as she spoke, remembering, but her eyes were dull and sad.

She stopped talking and the room fell silent. She kept looking towards the window. She was probably too pained to look us in our own eyes. The newspaper rustled inside the box on the floor and we all dived down to see Brandy waking up. She opened her brown eyes and we lifted her out and took turns at petting her. Michael brought in a saucer with milk in it and placed it down beside the cardboard box and the wee dog got up on her four paws and started lapping the milk, making slight splashing noises with her tongue. We all laughed at this.

‘Give her a wee bit of space and don’t pet her when she’s drinkin’ or eatin’; dogs don’t like that,’ said Michael.

Brandy finished the milk, licked it off her lips and nose, put her two front paws out in front of her, stretched and yawned with a slight squeak. It was the first noise she’d made. She then began to move unsteadily along the oilcloth floor. We followed her every move with squeals of laughter and excitement, and took turns at holding her in our warm laps.

Just as Uncle Michael said, ‘We’ll have to put some papers down for her …’, our Patrick jumped up from the sofa with the wee brown pup in both hands, saying ‘She’s pishin’! She’s pishin’!’ and put her back down on the floor where she continued peeing, looking up at us as we looked down at her, the pee forming into a yellowy puddle around her feet on the red-patterned oilcloth. Like Pineappleade. Everyone laughed, including Patrick, who went out to the scullery to get dried off.

We had our own dog! Brandy even rhymed with Dandy, the rat-catcher!

‘As I was saying about the newspaper!’ said Michael, and we all laughed again. I caught sight of me ma not laughing, though, and she continued to look out the window into the darkness.

‘I ordered me breakfast by phone from me bed the day he was killed, ye know,’ she said, smiling sadly towards Geraldine, who by this stage was waiting for more.

After a brief silence, Geraldine, looking a bit puzzled, said ‘But yous don’t have a phone, Eileen.’

‘Aye, we do! Aye, we do!’ we all replied, and Patrick bounded out to the telephone table, lifted the receiver of the phone and turned the dial with his finger. The phone dinged upstairs in me ma and da’s room.

‘See?’ me ma said, smiling to Geraldine, who nodded back to her, smiling as well. ‘It only works up and down the stairs.’ She went quiet again for a wee while.

‘He was a wile man, that Paddy,’ me ma said. She always called him Paddy, while a lot of other people called him Patsy. She also said he was a wile man, not is a wile man. It was the first time anyone had spoken of me da as was. She suddenly started laughing at her own recent memory of him.

‘He rings me up and says in a snobby voice, “Hello, Mrs Doherty, this is the hotel manager. Do you want breakfast in bed this morning?” I put on a snobby voice as well and said back to him, “Oh, yes please! Bring me two eggs, toast and tay up on a tray – and make it snappy!” “Did you say tay, madam?” he said down the phone, and I said, “Don’t be ridiculous, man! Of course I didn’t say tay! Now hurry up, man!” and put the phone down with a ding,’ she laughed, as she remembered. She looked both happy and sad at the same time, as she sat on the sofa telling her story. She was laughing but her eyes were tearful. We all laughed as well and were all ears for more.

She went on: ‘He brought the breakfast up and then took the four bigger wains to Mass. Glenn is a great sleeper and so’s Colleen, so I brought her into the bed beside me and went back to sleep.’ She went silent again for a few seconds.

‘It’s doing a cack!’ whispered our Paul, pointing at Brandy the pup, who was squatting down near the hearth over a watery, yellowy-brown cack. We all giggled as Michael lifted the wee cack with his hand through a sheet of newspaper and took it to the bin in the yard. As he came back in he said, ‘Tony, get Terry McKinney the marra and get him to give yous a hand wi’ the wee pup’s training. She’ll shite and pish all over the place unless she gits properly trained.’ Michael lifted the wee pup and went into the scullery with it. The rest of us stayed in the sitting room, wondering if me ma was going to say any more. After a few moments of silence, she started again.

‘Ye know, when he was shot, a man called Paddy Walsh came out to help him. He drinks in Mailey’s.’

Patsy nodded in agreement and said, ‘Aye, Eileen, that’s right. So he does.’

‘He crawled out on his belly as the soldiers continued to fire at him and Paddy. A bullet passed through his coat collar when he reached your daddy. He said an Act of Contrition in his ear as your father passed away.’

She fell silent again as she continued to stare into the blackness of the early evening.

***

I missed me da very much, but I didn’t put it in words to anyone except our Paul at night in bed. Paul and me, at eight and nine, were sent upstairs earlier than Patrick and Karen, who were ten and eleven. They were bigger and were allowed to stay down longer and watch TV with me ma or Uncle Eugene, or whoever else was in.

‘I really miss me da wile,’ I said to Paul as we lay side by side in bed. Paul was always on the inside, with me on the outside. The words nearly choked me and I could feel them tighten my throat. I’d been dying to say them all night but hadn’t.

‘Same as me,’ said Paul, with his head, like mine, resting back on the pillow and us both staring into the dark grey of the bedroom ceiling, which had an orange glow from the streetlights.

Before we went to bed, both of us knelt at the side of it to say our prayers. Me da had trained us to do it every night before we got in, and would kneel himself to say the Hail Mary and ask God to look after the family. Me and Paul kept doing it, saying the Hail Mary together and asking God to look after us all. I said to myself at the end before we climbed into bed ‘but me ma especially’.

After a while I heard Paul crying softly beside me. He’d turned his head to the wall to do it but I could tell he was crying. It’s in the breathing and the stiffness of the body. I felt that I could cry too then, and stayed lying on my back, staring at the ceiling, and let the warm tears come out the sides of my eyes and seep into the white pillowcase. When I turned to go to sleep later I felt the damp patch on my cheek, so I turned the pillow over to its dry side. Paul had cried himself to sleep.

When Karen and Patrick came up a wee bit later to go to bed, I pretended to be asleep but listened to them praying too, getting into their beds and then both of them crying silently into the night. I could tell by their breathing.

One night, as I was lying half-awake, my eyes shot open when I thought I heard me da whistling his way down the street towards our house, and I half expected to hear the front door opening as he came in. But the whistling continued on down the street, passing our house, rounding the corner at Foyle Road and fading away.

Each morning I woke up to a brand new day and, as my brain started to work its way out of sleep, everything was normal for a few seconds, but then I would realise, as I opened my eyes, that me da was dead. It was the same every morning.

2 Starman

There was a huge explosion around the corner on Foyle Road. We were at school when we heard it and the school shook slightly, the panes of glass rattling in their white-painted wooden frames. We heard explosions nearly every day; mostly bombs going off in the city centre, which was very close to our school, on the other side of the Derry Walls. Some would be close and others would be distant rumbles and tremors. A few times we were sent home early because of bomb-scares near the courthouse, just inside the Walls; too close for comfort. A wee boy in Primary Four by the name of Healy from Lone Moor Road, not far from our house in Hamilton Street, had his finger blown off after he lifted a detonator from the ground. The teacher said he was very lucky he wasn’t killed or injured worse. I didn’t know what a detonator was but was afraid to show myself up by asking. When the wee boy Healy came back to school a few weeks later he showed off his hand with his pointing finger missing along with half of the next one to it.

While the town centre was now considered a very dangerous place because of the IRA bombings, I still loved going up the town with me ma or granny or granda, or anyone else for that matter, as long as we went to Wellworths. Me granny used to go down the town from Creggan early on a Saturday for her messages to avoid the bombings. ‘I’ll have to get down the town for the messages before that oul bombin’ starts,’ she would say, as if the bombings started at a certain time, rushing out the door with her straw shopping bags over to the Creggan shops to get a Sticky Taxi. The Sticky Taxis ran from the Creggan shops to Rossville Street; people queued up and piled in when the taxi came, sharing the car. The bus service was hit and miss, as more often than not buses would be hijacked, driven across the road and set alight. No one ever hijacked the Sticky Taxis.

The Sticky Taxis got their name because people believed that they were set up by the Official IRA. In early 1970 the IRA had split into the Official IRA and the Provisional IRA. People, families, streets and neighbourhoods were divided as to which IRA they supported. Depending on what you were told, your beliefs usually led you to support one or the other, though many hedged their bets and pretended to support both. The Officials’ nickname was the Stickies, and the Provisionals became the Provos. The Officials began to be called the Stickies when, in 1971, they produced a green, white and orange Easter Lily badge with a sticky back to commemorate the 1916 Easter Rising. The Provisionals made a non-sticky badge, which needed a pin to attach it to your coat or jumper. They were called the ‘Pinheads’ for a while but the name wasn’t as popular as the ‘Stickies’. By 1972 both the Stickies and the Provos were fairly well armed, displaying their guns on foot-patrols and checkpoints in the Brandywell, where we lived, and in the huge Creggan estate where me granny and granda Quigley lived.

One Saturday me ma took me to Wellworths to help her with the messages. We walked down William Street and went through the British Army (BA) checkpoint on the corner, and as we did, the soldier asked me ma to open her bag. The soldier smiled at me ma but she looked straight through him and didn’t smile back. Another soldier asked me to raise my arms, which I did and me ma said, ‘He’s only a wain; what are you searching him for?’ and I thought, I’m not a wain, I’m nearly nine and a half! I raised my arms anyway and the soldier patted his hands along my coat, my waist and down the outside of my legs. This was the first time I was searched in my life and I couldn’t wait to get back to the street to tell everybody. When we got out the other side of the sandbagged checkpoint the soldiers called something to us and they all laughed, but we just walked on towards Wellworths to get the shopping. Some of the shops on Waterloo Street and Waterloo Place had been blown up and had barrels outside them with tape strung across to keep people out. You could see right into the backs of the shops which the bombs had gouged out. Other shops had ‘Bomb Damage Sale’ signs on their windows.

As luck had it, lorries used to dump bomb-damaged goods out on the Line (an old railway track that ran parallel to the river) behind the Mex army camp. Everything from clothes to food, to household goods and glasses got dumped, and we made it our business to scavenge through the rubble to get at the buried treasure in the form of trays of tinned stewed steak, Fray Bentos steak and kidney pies in their sealed tins, trays of tinned beans with sausages actually in the tin as well, rubber boots, kitchen clocks and annuals for girls and boys. One day Dooter McKinney picked up a box with four fancy glasses in it and when he took it home his ma sent him down to get another two as, apparently, they came in sixes! Dooter headed back out to the dump and sure enough found the other two.

One day, while out scavenging, we noticed a pile of long, brass army shells lying in a heap beside the bomb-damaged goods. Terry McKinney said they were flare shells fired by the BA from the Mex to light up the area at night in search of IRA gunmen. They were shaped like bullet shells only much heavier, fatter and about eighteen inches longer. We took two each home with us, shined them up with Brasso, and me ma and Maisie McKinney put big plastic reeds into them and used them as ornaments, sitting on the floor on either side of the hearth in the sitting room. When the other mammies in the street saw them or heard about them, they sent their wains out to the dump to bring them back two as well. Soon, almost every hearth in the street was adorned with the BA flare shells.

***

In Wellworths, you had to pass the sweet counter and then the cake counter on the way in. Some of the sweets came in purple, red, orange and green wrappers, some had see-through plastic wrappers, and others had none. They were all stacked there in their thousands, laid out in terraces as me ma called them, starting low at the front of the counter where the customer was and rising gradually towards the back, where the women shop assistants stood in their white coats and pretty make-up.

If the sweet counter sugared the senses, then the delights at the cake counter drew them out as slabbers to the chin. It was truly hard to take in. Like the sweet counter, the cakes were laid out in compartments on a slight slant so you could see the full range of them. Huge, square chocolate cakes of different varieties with chocolate cream in the middle and cream piped along the edges, sponge cakes with jam and cream in the middle and a dusting of icing sugar on the top. Swiss rolls over two-foot long, covered in chocolate, or just brown without the chocolate, so you could see the flash of the white cream on its rounded end, and ordinary Swiss rolls with the cream and jam oozing out.

Seeing the look on my face as we passed by, me ma said, ‘Don’t worry, son, we’ll get a slab o’ cake on the way out,’ and with these reassuring words, I happily traipsed onwards with her to get the messages.

‘Hi, Ma, look at this! It’s a dog-food called the same as our Brandy!’ I loved calling Brandy, ‘our Brandy’, as it was great having a dog. I held up the red tin with a sheepdog on it for her to see.

‘Oh God, so it is. Grab a tin o’ that and we’ll see if she likes it,’ me ma said.

‘Was there no dog-food dumped out the Line?’ she asked and I said naw but I’d look again the next time.

We were passing the café at the back of the shop when me ma said, ‘Will we go in for a wee bite, Tony?’ and I said ‘Aye’, and in we went. I sat down at a square, white table on one of the orangey-brown chairs, and me ma joined the queue and chatted to the women and girls behind the counter. I remember wondering how she knew everyone when we were up the town, as all you heard was ‘Ach, yes Eileen’ or ‘What about ye, Eileen?’ and me ma would say ‘Yes, Susie, aye, grand, Susie,’ or ‘Not so bad, Mary. What about ye, yerself?’ and then they would turn their backs to me and continue a whispered conversation, presumably about her and us living after me da dying.

Both of us got fish and chips, and tea, bread and butter. She brought it down on a tray and we sat down to eat. I finished mine, but me ma didn’t finish hers. She just sat looking around her, eating her white bread and butter and drinking her tea. I was worried about her not eating her fish and chips. I was worried about her living without me da.

The café was buzzing with mothers, grannies and young wains at tables.

‘D’ye see that wee woman there with the wee brown hat?’ me ma asked me, nodding to somewhere behind my head.

I turned around and saw a wee woman with a wee brown hat and a brown overcoat, sitting with her back to us a few tables down.

‘Aye, what about her?’

‘She’s a store detective; she works for Wellworths,’ she said.

‘What’s a store detective?’ I asked her, smiling and thinking she was taking the hand, like me da used to.

‘She walks up and down the aisles lookin’ out for people shop-liftin’. She thinks nobody knows her, but everybody does. She’ll get up now in a minute. Wait to ye see.’ And, sure enough, up she got with her wee straw shopping bag, dandering back into the aisles, where my eyes followed, and her not lifting any messages, but just walking up and down the aisles, now and again letting on to be interested in something but always looking around her at the other shoppers.

Me ma was true to her word about the cake, as we got a slab of Victoria sponge and a bag of assorted biscuits. These would be devoured as soon as we got home by the hungry Dohertys. We went up to the till and packed the messages into Wellworths’ white plastic bags with navy blue polka-dots and the Wellworths name on in large, orangey-brown writing, and headed home through the same checkpoint we’d come in by. The whole of the city centre was ringed off by checkpoints by this stage; you couldn’t get in without going through one of them to be searched. On the odd occasion we crossed over Craigavon Bridge to go to the Waterside, you had to pass a sandbagged checkpoint sitting squat in the middle of it, the soldiers and RUC men stopping and searching cars travelling in both directions.

‘We’ll see if we can get a Sticky Taxi out to the house,’ said me ma as we walked up William Street with the packed shopping bags.

‘There’s me granda, Mammy!’ I called out, excited to see the tall, burly figure of me granda appearing from the red-brick terrace of Chamberlain Street, carrying a handful of pale-yellow bookie dockets. He approached us with a broad smile, and me ma said, ‘Yes, Daddy, were you over at the bookies?’

Granda said aye he was, and that he was heading up to Tracy’s Bar if she fancied passing the hour. Me ma said ‘Aye, surely,’ and we turned around and headed back up to the end of William Street, past all the large-windowed shops, towards the bar, just across from the BA checkpoint. There was a queue of women and wains on the street waiting to go through and be searched. The barrel of an SLR rifle pointed into William Street through a wooden frame built into the sandbags.

I loved the odd occasion when I would be taken into Tracy’s. The last time was a few months before with me granda, when he took me down the town for my birthday and bought me black Gola football boots with golden stripes on the sides. I carried the orange McLaughlin’s Shoes bag with the black writing on it into the bar, and the men, me granda’s friends, asked me to show them the new boots. I took them out and put them on the bar, where they stood proud on their rubber studs beside the brown bottles of Guinness stout and small whiskey glasses, to be admired by one and all. Me da was still alive then.

We went in with me granda and the bar was packed. There was a radio on for the horse-racing and some of the men were gathered round it with their bookie dockets clenched tight in their hands. ‘What d’ye fancy, Eileen?’ asked me granda as we sat down.

‘I’ll take a wee brandy wi’ ice ’n’ water, Daddy,’ she said.

‘A wee coke for you, Tony?’ asked me granda, and I nodded back to him.

Apart from the few men gathered round the radio at the end of the counter, all the other men in the bar were looking in our direction and a few raised their thumbs at me and smiled. One came over, a tall man with long, curly hair, a beard and a brown suit, who me ma called John Keys.

‘What about ye, Eileen?’ he asked, sitting down beside us on one of the hard wooden stools.

‘Aye, grand, John,’ said me ma. ‘I have to get on wi’ it.’

‘Patsy Doherty was a great man, Eileen. The best there is,’ said John.

‘I know he was, John,’ said me ma. ‘I know he was.’

‘And how are you, big fella?’ he said, putting his hand on my head and ruffling my short, dirty-fair hair.

I reddened in the face, mumbling that I was OK.

‘Are ye lookin’ after yer mammy?’ he asked, and I smiled and nodded back to him, still embarrassed.

‘Oh, he’s good to me, that boy. They all are. They’re a credit,’ said me ma with a smile, showing her perfect white teeth, a beautiful feature in her now often sad face. She still kept her dark brown hair long and straight and parted in the middle, the way it had been for years.

‘Here ye go, Eileen,’ said me granda, as he placed me ma’s brandy down on the table and handed me a bottle of Pepsi and a straw.

He sat down with his bottle of stout beside me and me ma and John, and me ma told them about the soldier searching me at the checkpoint.

‘I told them,’ she said, ‘that he was only a wain but they didn’t take me on.’

‘What did they do, Tony?’ asked me granda.

Embarrassed, I said, ‘He told me to lift me hands up and then he searched me coat and rubbed down the outside of me trousers.’

‘Imagine that,’ said John to me ma and granda, ‘searching the wee boy. They’re a shower of English fuckers, I swear to God!’

‘Aye, sure, what can ye do?’ said me ma, and after a short pause, added, ‘Hi, there was a house blown up around the corner from us yesterday, where the Slavins and the Hales used to live. The army had the house sealed off when we left the street this mornin’.’

Éamonn Slavin was in my class in school. They had moved from the house which was now blown up to a new housing estate called Carnhill, down near Shantallow, out in the country. When we went home a few hours later, carried across Rossville Street and Lecky Road in a Sticky Taxi which, after dropping us off, was bound for Creggan, me, our Paul and Dooter McKinney went round to see the house. As well as the Slavins, Snooks Hale, who was a year older than me and in our Patrick’s class at Long Tower, used to live there but the Hales had moved to Creggan. Most of the roof and front wall had been blown out by the bomb. It looked like a doll’s house: from the street you could see right in and out the back windows, which were all blasted out, and you could see the ends of the ceiling and floorboards and the gap in between, facing out into the street.

The BA had gone by this time so we were free to go in for a look. When we went in, the front room was not as bad as the upstairs. A huge statue of Our Lady leaned against the wall beside a display cabinet with red velvet shelves, on which were china cups and teapots. There was a thick layer of dust on the top and on most things but it looked much like anybody else’s front room with its fanciness of furniture and good carpet. We couldn’t go upstairs because it was blocked by rubble from the bomb. We didn’t lift or take anything because it all still looked as if it belonged to somebody, and it even felt strange going in through the wrecked downstairs.

When we went back home later I told me ma we were in the bombed house and she told me that all the furniture still belonged to someone and not to go back in, that it wasn’t our house and it could be dangerous.

‘What d’ye mean – another bomb?’ I asked, and then there was a knock at the front door and when I went out to answer there was a priest with a broad smile standing there.

‘Is your mammy in?’ he asked, and I thought he was there to complain that me, Dooter and our Paul had been over at the blown-up house around the corner. I went back in and told me ma there was a priest at the door and she told me to bring him in.

Father Tom O’Gara came in that early evening and spoke to me ma in the scullery for a while and then came in and sat with us in the sitting room and had our fry with us as we watched TV. He started coming to the house for visits and often brought his guitar with him. Father O’Gara was from Moville in Donegal, but was one of the priests serving at the Long Tower Chapel. He had a mop of browny-red curly hair, a kind face and a pleasant way about him. He was with me ma a lot of the time. He’d call for her in his navy-blue Hillman Avenger to take her out for runs. Sometimes some of us would go as well. He kept his guitar in the boot and when he played it in our house, we’d sing ‘Bridge Over Troubled Waters’ and ‘Moon Shadow’ in the sitting room. He’d play anything you asked him. Uncle Eugene and Father O’Gara got on very well together.

Me ma said that there was an ‘Inquiry’ into the killings on Bloody Sunday, and that she’d have to go up to Coleraine every day to attend. I wasn’t sure what an Inquiry was. I’d never heard the word before, but it sounded like someone was going to do something about me da’s death and the deaths of the other twelve men that the BA had shot dead. I think she did go nearly every day. Father O’Gara took her up in his car most days, when we were at school. Me granny Sally or me aunts would watch Glenn and Colleen for her when she was away at the Inquiry. In the evenings it would be dark by the time she came back, leaving Karen in charge of making the dinner. Me and Patrick helped out and, between us, we kept the house clean and everyone fed. Maisie McKinney called in often from up the street to make sure everything was all right.

It was Aunt Geraldine who encouraged me ma to learn to drive. One evening there was a knock on the front door and me ma got up from her chair, saying excitedly, ‘That’ll be Junior McDaid for me,’ and we all went out to the street to see. Sure enough, it was Junior and he put me ma in the driving seat. After a few minutes she started the car and drove down the street towards Foyle Road. The car shuddered and jolted a few times on its way towards the corner before going smooth. Me and our Paul ran after it for the craic, following it down to the end of the street. We saw the indicator light come on to go left and the car turned the corner and disappeared down Foyle Road. She went out driving with me Aunt Geraldine as well in her wee white, two-door Vauxhall. Very few families in our street had a car, and no other woman in the street could drive. Me Aunt Geraldine said that me ma was a natural driver and that she took to it like a duck to water.