5,85 €

Mehr erfahren.

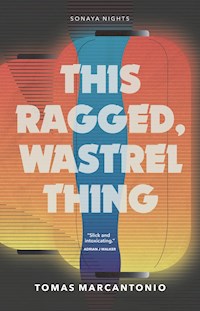

- Herausgeber: STORGY Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Sonaya Nights

- Sprache: Englisch

BOOK ONE OF THE SONAYA NIGHTS TRILOGY

After serving eleven years in The Heights for the murder of his childhood sweetheart, one-eared vagabond Daganae Kawasaki is finally free. But beneath the neon glare of a sprawling Sonaya, he soon discovers the backstreets are bursting with strange new shadows. Confronting plucky street orphans, bitter biker girls and down-and-out expats, Dag is swiftly embroiled in a fresh homicide case – and finds his murky past isn't done with him yet.

“I really enjoyed This Ragged, Wastrel Thing – a dystopian noir set in gloomy, booze-drenched streets crawling with scoundrels. Tomas Marcantonio’s writing is slick and intoxicating.”

Adrian J Walker - Author of The End Of The World Running Club

“This Ragged, Wastrel Thing is alive with colour, energy and vibrant language. Marcantonio possesses the rare ability of enticing the reader to turn the page, not only to discover what happens next, but to experience yet another visceral and original turn of phrase. A beautifully vicious read.”

Adam Lock - Author of Dinosaur

“This Ragged, Wastrel Thing is a neon distorted, gritty reflection of humanity and its quest to find belonging – dystopian novels haven’t had it this good since Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaids Tale.”

Ross Jeffery - Author of Juniper and Tethered

“A cinematic and theatrical neo-noir painting dripping old-school masters of the genre on to a new canvas using rare concentrated pigments. With beautifully rich backdrops, scenes and characters – it’s a real treat for the imagined senses.”

John Bowie - Author of Untethered

“A beautiful mash up of grim noir and Japanese flare with a beating heart of motorhead vigilantes. Sons of Anarchy meets Sin City.”

Dan Stubbings - The Dimension Between Worlds

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 379

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Praise for Tomas Marcantonio

“I really enjoyed This Ragged, Wastrel Thing – a dystopian noir set in gloomy, booze-drenched streets crawling with scoundrels. Tomas Marcantonio’s writing is slick and intoxicating.”

– Adrian J Walker– Author of The End Of The World Running Club

“This Ragged, Wastrel Thing is alive with colour, energy and vibrant language. Marcantonio possesses the rare ability of enticing the reader to turn the page, not only to discover what happens next, but to experience yet another visceral and original turn of phrase. A beautifully vicious read.”

– Adam Lock – Author of Dinosaur

“This Ragged, Wastrel Thing is a neon distorted, gritty reflection of humanity and its quest to find belonging – dystopian novels haven’t had it this good since Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaids Tale.”

– Ross Jeffery – Author of Juniper and Tethered

“A beautiful mash up of grim noir and Japanese flare with a beating heart of motorhead vigilantes. It’s Sons of Anarchy meets Sin City.”

– Dan Stubbings – The Dimension Between Worlds

“A cinematic and theatrical neo-noir painting dripping old-school masters of the genre on to a new canvas using rare concentrated pigments. With beautifully rich backdrops, scenes and characters – it’s a real treat for the imagined senses.”

- John Bowie- Bristol Noir

“Within the first pages of Tomas Marcantonio’s searing new book, we are utterly caught up in the crazed action of a world alight with neon fire. Filled with stunning imagery that blends beauty with horror, and sanity with absurdity, the language gives life to a world that feels so intensely realised it is as though we are walking the streets alongside Dag, Fairchild and co. With elements of Watchmen – particularly Rorschach’s diary – but also of Philip. K. Dick, and Ballard, This Ragged Wastrel Thing is entirely unique and never anything other than compelling and exciting.”

- Professor Wu - Nothing In The Rulebook

“This Ragged, Wastrel Thing is a brilliant debut, wonderfully executed by Tomas Marcantonio. Not many futuristic noir novels can be described as retro but This Ragged, Wastrel Thing has pulled it off and it gives the book a really unique feeling. The odds are it wasn’t on your radar previously, but it needs to be.”

- Fallen Figs Book Blog -

“The descriptions of Sonaya are extremely vivid and captivating; the blinding neon-lit streets, the dingy, seedy bars and alleyways, and the smells and sounds of the city which creates an atmosphere and tone that is incredibly unique and realistic. Marcantonio does a fantastic job at building a sense of tension throughout the book that culminates in the final pages – I cannot wait to jump back into the bizarre but wonderful world of Sonaya in the next two books of this trilogy.”

- On The Bookshelf -

“Tomas Marcantonio has written an entertaining noir that sits comfortably between ‘In the Miso Soup’ by Roy Murakami and ‘The Plotters’ by Un-SunKim. Dark black shadows splashed with blade runner neon nuances provide the perfect backdrop to a world alien to even the most adventurous tourist. Easy to read with clever turns of phrase, This Ragged, Wastrel Thing could be the start of a bold series.”

- Sebastian Collier -

“This witty, futuristic, dystopian noir has some fucking pair of legs! It hits the ground running and doesn’t let up until the very last page. It’s all drugs and guns and soju and sake; grungy bars and rooftop parties, metalhead biker chicks and corrupt politicians; revenge and deception and dark city underbelly. Sonaya is an absolutely brilliant and fascinating character all on its own, and our protagonist Dag is one of the most strangely likeable leads I’ve read in ages. Go and get yer mitts on this one!”

- The Next Best Book Blog -

STORGY® BOOKS Ltd.

London, United Kingdom, 2020

First Published in Great Britain in 2020

by STORGY® Books

Copyright TOMAS MARCANTONIO© 2020

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the express permission of the publisher.

Published by STORGY® BOOKS Ltd

London, United Kingdom, 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Edited & Typeset by Tomek Dzido

EBook ISBN 978-1-9163258-1-4

Cover Design by Rob Pearce

For Jung-mi, who led me through the backstreets.

“Unfortunately, the clock is ticking, the hours are going by. The past increases, the future recedes. Possibilities decreasing,

regrets mounting.”

- Haruki Murakami, Dance Dance Dance -

Contents

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINTEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

TOMAS MARCANTONIO

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

EXIT EARTH

SHALLOW CREEK

HOPEFUL MONSTERS

STORGY MAGAZINE

The Rivers. A spiderweb of alleys for the drunk and destitute, weaved together from stones and shadow. Winding backstreets forking off like rotten veins plunging into every shady corner. The greasy smell of glass noodles and exhaust fumes from late night scooters. Neon blinking on every grimy surface and crooked alleys disappearing into a black and sorry night. Home.

Sonaya was always a little rough around the edges, but now The Rivers are deeper, dirtier, wilder. Not that that’s a bad thing; the Japanese way was always too rigid for my liking, and Sonaya’s got its own mad personality. But man, you walk around the Rivers at night after eleven years away and you start wondering what the hell went wrong. This is the real Sonaya right here: alleys backed up with rusted scooters, cockroaches scuttling through pancakes of vomit, shady characters leaning on uneven walls. I fit right in, and that’s not a thing to make a man feel proud.

Me and this city are one and the same. The Japanese aren’t all bad, but spend too long in Sonaya and the coat hanger across your back soon disappears. You stop bowing to people and forget the niceties. The Japanese are too damn stiff; walk and think in straight lines. Sonaya’s got a lot of flaws, but rigidity isn’t one of them. This is a city for the flexible, and I’m damn near elastic. I don’t just walk these streets; I’m bonded to their blood. Riding the plasma wave straight to the heart.

Now that I’m out I’ve got a lot of friends to see, and not all of them are waiting inside bottles. But hell, I’m in no rush. I’m a free man for now and every night ahead is young. But first I’ve got a debt to pay. There’s an old saying that states a man in debt is no more than a slave, and I don’t like to be a slave to anyone but my own joyous whims. There’s another saying that you’re a long time dead, so once I’ve paid my debt I’m gonna drink long and hard.

The girl’s name’s Jitsuko—Jiko for short. I’ve only met her once before, but I’m good with faces. Hair dyed red like a forest fire, skin like a winter moon, and upturned eyes like a fox. It doesn’t take long for old Kosuke to find her for me.

‘She’s one of those Bosozoku creatures,’ the old man told me. ‘They make an absolute racket down in the Rivers at night, that rabble.’

I smile. Bosozoku, last of the biker gangs. Their numbers increased when the city went to shit. Just kids rebelling against nothing and everything, tearing up the streets and making a nuisance of themselves. Kosuke’s right; I can hear them long before I spot their bikes. It’s a good job half the city’s nocturnal.

I’m down near Ryusui Station at The Cross, the five-way confluence of the Rivers’ busiest streams. An old drunk with fish hook eyebrows slides along one wall, spit catching on his stubble as he screams obscenities at the holes in his leather shoes. A pair of addicts woodlouse together in a doorway and watch me pass with hungry, globular eyes. The homeless skunks wander their nightly aimless wanders, waiting for the moon to fall from the sky and crack open to cover the world in a new yolk.

All these holes are new to me. It used to be that I knew every underground bar and every kitchen that kicked rats out the back door. The blinking neon signs spell different words but the doors are as sad-looking as before; crooked basement stairs, windows dim or boarded up.

I soon find what I’m looking for: two wine bars east off The Cross, basement bars that bottle and sell the cheapest kind of grape. The apartment blocks were here long before I lost my job; their grey walls etched with rust trails bleeding from each twisted railing.

I descended the stairs to Vino Ryusui and pushed through the gnarled door. It’s dark and empty; only a few flickering candles flinging light over the red oak tables. No one’s waiting to show me to a table. Several girls perched on stools at the bar stop talking when they see me.

‘What d’ya want?’ one of them calls over. This is the hospitality of the Rivers. Another two get up and stand between me and the bar. Neither of them is Jiko.

‘Got anything from Argentina?’ I ask. ‘I’m looking for something dry, preferably from Mendoza.’

They look at each other like cartoon bodyguards and tell me to leave. The short one’s hair is dyed blonde, a bob down to her shoulders that frames her mousey cheeks and coated cherry lips. The tall one’s hair is purple, with a fringe straighter than the sharp end of a cleaver; she’s wearing so much black eyeliner it’s like she’s taken two clean punches. Together they look like an anime girl group, only with more tattoos and fewer smiles.

‘I’m looking for Jiko,’ I say. ‘Owe her some money for a favour she did me.’

‘You can just leave the money with us,’ Purple says, her face as friendly as a crowbar. ‘We’ll make sure she gets it.’

‘I’d like to see that she gets it myself.’

‘Jiko’s on a ride tonight,’ Blonde says. ‘She’s fast, but the sun usually beats her home. Come back tomorrow.’

‘I’ll be drunk tomorrow. Jiko’s money’s only safe until I find some Mendoza wine.’

Purple still looks pissed but Blonde’s face breaks into something like a smile.

‘Wow, look at that,’ I say. ‘I was starting to wonder if either of you had teeth.’

‘Try Sakura,’ Blonde says. ‘Down in the pleasure quarter. You’ll find Jiko there. Follow the screaming and you can’t go wrong.’

I throw her a wink and turn on my heels.

‘Wait,’ Blonde says. She walks over to the bar and I examine her tattoos; a mugunghwa blossom along her left arm and a tiger straddling the Korean taegukki on the small of her back. She pours something burgundy into a glass and the tiger scowls. ‘This is Sonaya,’ she says. ‘You’ll be waiting a long time for something from Argentina. You new here?’

‘Been away a while.’

She smiles and hands me the glass. I throw it down my throat like plum juice.

‘Best wine I’ve had in eleven years,’ I say, and I disappear into the night.

My first buzz as a free man. Who needs a job when you’ve got the charm of the Dag. I could sweet-talk in basement bars all night and feed on bottomless free drinks. I’ve got a nose that’s broken in two places and a gaping hole where my ear used to be, but neither makes a damn bit of difference. The government might have me down as a five on their tax records, but talk to me nose to broken nose and you’ll jot those points back up as soon as I open my mouth.

That lick of wine is tingling in my throat and I’ve got a stirring thirst for more. A Great White Shark with blood on his tongue, swimming in a sea of wounded seals. I better get this Jiko thing out of the way before I blow all of Kosuke’s cash on the destruction of my liver. Time to dive into this new Sonaya. Deep breath now.

I prowl the pulsing lanes. One step, two step, the Sonayan waltz. You don’t need a sixth sense to know where the pleasure quarter begins. Red neon blazes through the caterpillar streets, like kisses from the maroon lips of Sonaya’s whore goddess. The girls and boys are all in heels and the flickering lights above their heads throw slick-hipped shadows across the walls.

‘Looking for some action?’ one of them asks as I pass, my eyes fixed on the shifting signs above. Japanese, Korean, English; it doesn’t matter, all of them have at least one character that’s blown its bulb and make the rest wink like a senile aunt.

Things sure have changed since my last visit to the pleasure quarter. It used to be just a few girls with short skirts and sly glances. Now there are different buildings to suit every desire. Homework Clubs and singing rooms and dark basements I don’t even want to know about. Maybe the people in this city aren’t so lonely after all.

I pick the threads of the web for a while with no sign of Sakura. There are plenty of screams for sure, but not the kind you want to hear. I stop beside a lady propped against a wall to ask for directions. She’s tall and has thick purple lips; she’s got heels that could take an eye out, and eyes that look like they’d enjoy watching it happen.

‘You’re into them young, are you?’ she says, her voice gruff, like it’s been trawled across the ocean floor.

‘I’m just looking for someone,’ I reply.

‘You all are,’ she says, her heavy eyes sliding to the right. I follow her gaze and find what I’m looking for down the next alley. Sakura. Cherry Blossom. It’s damn ugly from outside; sickly pink and peeling paint, like someone’s chewed up a bunch of cherry blossom petals and spewed all over the walls. Things don’t look much better inside; flowers and frills and pink everywhere; a small reception desk covered in plush toys, a torn and tattered chaise longue and wallpaper covered in faded hearts, all of which makes you feel like you’ve been dropped into a giant box of confetti.

The girls on the chaise longue jolt when they see me, each of them in school uniform; white shirts, black ties half-undone, navy socks up to their knees. Fifteen, sixteen, at most. It’s strictly talking only in Homework Clubs. Smiling and leering; old suits tired of nagging wives, pretending to help with homework as girls flutter eyelashes and occasionally graze a leg. The men drink hard liquor and the girls sip juice through straws. All above board, this is as innocent as it gets. But this is just the start.

‘Welcome, sir,’ the oldest girl says as she slips behind the front desk and flashes me a yellow smile. Her hair is pulled back in a ponytail and secured with a white bow, her Tokyo accent lingering in the air like the sickly sweet after-taste of melted candy floss.

‘Would you like a private meeting, sir? Is there a girl you usually see?’

I look around. No screams. No flashes of red. No Jiko.

‘I’m looking for Jitsuko. She here?’

The girl tilts her head to one side and grants me a closer look at her grimy canines. ‘I’m afraid we don’t have a girl by that name, sir.’

I hear a man shouting upstairs, closely followed by the sound of a door slamming.

‘Never mind,’ I say.

I take the stairs one at a time. I’m no slouch but I’ve got a reputation to maintain. When a man loses his cool he’s lost it all, like a snake shedding its skin; there’s no going back. At the top of the stairs I see Jiko at the end of the corridor, dressed in black leather trousers and a tank top, the fiery rays of a Rising Sun tattoo spreading across her collarbone. She’s pointing a gun at a middle-aged suit with glasses and a comb-over, and he’s screaming at her like he’s trying to strip the flowers off the wall. Two girls are peeking out of an open door behind him.

‘Throw your wallet on the floor.’ Jiko orders the suit.

Her finger hovers above the trigger, eyes firmly locked on her target. If she’s seen me, then she’s not letting on. The suit swears and inches his hand inside his pocket. He removes a wallet stuffed with notes and tosses it to the floor between them. The wallet spins and slides into one of Jiko’s oversized boots and she takes one hand off the gun to retrieve it. With a solitary hand, she empties the wallet and slips the wad of notes into her pocket.

‘That didn’t hurt that much, did it?’ She throws the empty wallet back to the floor.

‘This isn’t over,’ the suit says as he moves towards his wallet. ‘I’ll have your guts, girl.’

‘Yeah, they all say that,’ Jiko answers.

She lowers the gun a second too soon. She didn’t see what I saw; the suit planting his feet on the floor, wiping his fingertips against his trousers. Jiko looks like she knows what she’s doing, but it takes years of experience to know when a crazy cat’s about to pounce. In a flash he’s grasped her gun and they’re wrestling like a pair of kittens over a ball of yarn, only this yarn might explode and send red furballs flying across the hall.

The schoolgirls in the doorway are screaming and I shove them inside and slam the door in their faces. I keep my eyes on the barrel of the gun and make sure I’m not in range as I approach the struggle. Jiko’s surprisingly strong but the man’s no mouse either. He elbows her in the face and wrestles the gun away from her as she falls to the floor with fresh bruises and blood.

Normally I wouldn’t get involved, but I’ve got a hell of a debt to repay. Gotta wipe that dust from my shoulders before I can enjoy my freedom. I reach down to my ankle and remove Old Trusty from its sheath. My beautiful Wharncliffe blade. Been with me since my days in the force. Spent the past eleven years in a box in the basement of The Heights, but it still feels like my eleventh finger; I brandish my blade as fast as another man might scratch his nose.

Time slows down in situations like these. I haven’t been a cop for years but you never lose the instincts. You see action play out like photographs, and if you’re good, you can smudge your prints all over them before you reach the end of the reel. The suit’s standing over Jiko and pointing her own gun at her. Whether or not he’s gonna shoot, I’ve no idea, but I don’t wait to find out. I slam Trusty’s handle onto the sparse scalp in front of me, and both scalp and body tumble to the floor.

‘This your first hold-up or what?’ I ask Jiko.

She pushes the suit’s limp body off her and I help her up.

‘First one today,’ she says. ‘You put me off. I saw you lurking by the stairs. How’d your tax assessment turn out?’

‘I got a five.’

‘Congratulations. Result like that must save a man a lot of money.’

‘That’s why I came to find you. I told you I would.’

Jiko looks at the suit on the floor and plants a boot in his stomach. ‘I hate these old pervs,’ she says, shouldering past me to the room with the girls inside. She opens the door and hands them a roll of notes. ‘Go home,’ she says, and closes the door.

‘Let’s get out of here.’

Whoever designed this prison was smart. The worse the crime, the higher the cell. I’m up on sixty-third with the other murderers, and from here you get one hell of a view. The harbour, the old town, the lights on Broken Hill. The skyscrapers by the waterfront, the back alleys of the Rivers. They want us to see, see what we’re missing. Maybe they’re teasing us, taunting us with a world that’s forever out of reach. Maybe it’s to make us appreciate the city more, so we never sin again.

It’s been ten years. Seven months to go, and I’m a free man. I’ll finally get out of this fucking cell, but who knows if it will make a difference. Every night when the lights go out I listen to the screaming. Most of those on sixty-third have lost their minds. They howl like wolves at the moon and keep me awake. The ones with any semblance of sanity smash their skulls against stone walls. Their heads sound hollow. Maybe mine is the only one that’s not.

Sometimes moonlight shines through the bars, paints black stripes across my face. I stare at the moon and think of one thing only. Ten years on and my mind still bumbles around that one night like a moth against a naked bulb that I can only beat my broken wings against. But it’s never enough. My brain just flickers on and off, flashes in the dark, a film chopped up and thrown at me in fragments. No matter how hard I try to piece it all together, I always fail. I just can’t work out why. I can’t work out why I did it.

They say that when one life ends, another begins. Prisoners never escape from The Heights, but last night a body left the building. For five seconds Song Ye-jin was free with wind in her face and lights in her eyes. This morning they were still picking up her splattered flesh and shattered bone off the pavement. They’re probably still trying to wash away her blood.

New life usually means screaming babies with clear consciences and bald, pug-eyed heads. This guy walking into the mess hall doesn’t fit the bill. Five foot eleven, thick-rimmed glasses, a twitchy nose. Everyone knows who he is. There aren’t too many foreigners in Sonaya, and even fewer who play the game. An American in The Heights? He’s already a damn celebrity.

I wouldn’t usually have anything to do with the dregs below, and all they have on this guy is possession with intent to supply. That’s just rabbit food in this city, hardly worth the cell. But towards the end of his first week he walks over and introduces himself, like a pimp from the seventies; khaki threads two sizes too big, a perm like a wig on a giraffe, and tortoise-shell, thick-rimmed glasses that won’t last the week. He sits down opposite me during lunch and doesn’t look the least bit nervous.

‘Dustin Fairchild,’ he holds out a hand.

I take it. ‘Daganae Kawasaki.’

‘I’ve heard of you,’ he says.

‘Good. Then you’re not as stupid as you look.’

Whatever happens next will decide the comfort of his stay. For a moment I think he’s gonna get up and clear on out, but he simply smiles, an American smile; lop-sided and overconfident.

‘They told me you’re a good person to know,’ he says.

‘I’m not. I’m a damn hurricane. You like hurricanes?’

‘I like people who tell me I look stupid.’

I take a clap at my food. Plain white rice, a side of spinach. Spinach is a good day.

‘You look stupid,’ I repeat. ‘How long you been in Sonaya?’

‘Two years. Came here on work, assignment for a paper. New Jersey.’

‘The Garden State. You’re in the wrong city, then. See this spinach?’ I pinch a leaf between my chopsticks and hold it up between us. ‘There’s more green on this plate than in half the Rivers. What were you writing?’

Fairchild shrugs. ‘About the things that cops paid me to stop writing.’

‘Let me guess. The sex trade. Drugs. Political corruption.’

‘I got a bit too wrapped up in the stories, if you know what I mean,’ he smiles that lopsided smile again. I like this guy. My kind of idiot.

‘I’m guessing the paper isn’t waiting up on you,’ I say.

‘I lost that gig a long time ago. Police wanted to hush me up, and to be honest, I enjoyed being hushed up. It got me into a lot of parties. They saddled me with a two-year sentence, but I’m not worried. They reckon I’ll be out in a couple of months. We’ve got some good lawyers in the States, and anyway, I won’t be short of work, not after this. A few months in The Heights, that’s a book right there. They should’ve thrown me in here to start with. Would’ve saved a lot of time.’

I plough through my rice. Gotta save the spinach for last.

‘I hear you’ve got a pretty interesting story yourself,’ he says.

I look up and stare at his eyes. I try to decide which liquor bottle shares their colour. I settle on soju. ‘I’m on the sixty-third floor,’ I say. ‘If I didn’t have an interesting story I wouldn’t be up there.’

Fairchild’s left eye twitches. Or maybe it’s a wink. ‘I heard you murdered your girlfriend.’

I put my chopsticks down as slowly as I can and use my tongue to search for a stubborn grain of rice wedged in my teeth.

Fairchild holds his hands out like he’s just finished a magic trick. ‘What? I told you I’m a journalist.’

‘And I told you, I’m a hurricane.’

The next time I see Fairchild I’m in my cell. The man must have some powerful friends if he’s already hopping floors like a damn jack rabbit. Either that or he’s got a nice stash of notes stuffed under his mattress.

My cell suits me fine. Ten foot by ten foot of cold stone. A firm mattress on the floor. Clean sheets every week. A sink with only two small chips and a working toilet without a lid. I’ve even got three whole walls to lean against.

I’m a damn sweetheart compared to the other deadbeats above the fiftieth floor, and that gives me the only advantage I need: weekly access to the library. I’m not a fussy reader; anything with words is fair game, I’ll gobble through it just the same. I even read the newspaper when I can get my hands on it. After the government decided that commoners couldn’t be trusted with the internet, papers came back in a big way, but there’s only one left that does the rounds. The Daily, owned by the same hyenas who run the island. The internet was full of shit, of course, but that’s all done with. Now The Daily is like The Bible; facts are ‘verified’ by the suits, and suddenly we’re a nation of believers.

When Fairchild appears at my cell, I’m leaning against the only wall that catches any sunlight. He even knocks on the open cell door, the softie.

‘Come,’ I say, not looking up. I’m reading up on the elections. Still a few months off, but there’s no harm in doing my homework early. If all goes well, I might even be a free man by the time elections come around. A free man with a vote to my name, too.

‘You got a minute?’ Fairchild asks.

What a cutie. I scan him up and down and return to my paper. ‘About a million of them,’ I say. ‘If I could sell them I’d buy the whole damn island.’

He enters all sheepish, and I watch his eyes dart around behind his glasses, like he’s already looking for an escape route; a hole in the wall. He scratches his nose with the back of his finger.

‘What’s your candy, Fairchild?’ I ask.

He blinks at me like he forgot I was there.

‘I know what a man looks like when he goes two weeks without a fix. What’s yours?’

‘Nothing big,’ he says. ‘Just the white stuff.’

I look back at my paper but I don’t read it. ‘You’ll have to learn to live without it. Doesn’t matter how deep your pockets go, you’re more likely to see a hot tub in your cell than a bag of pollen.’

He nods fiercely and sits down beside me. Look at me, I’ve made a friend.

‘You know a guy by the name of Tsubasa?’ he asks.

‘One arm and hair like a banshee? Yeah, I know him. Been giving you trouble?’

Up close, Fairchild’s skin doesn’t look too good. His nose is pockmarked and red blotches cover his cheeks.

‘He’s been watching me, asking questions.’

‘So what?’ Poor Fairchild. Foreign boy in a foreign prison. ‘Don’t worry, you’re not his type, if that’s what you’re thinking. He’s a plover, that’s all.’

His eyebrows scrunch up and reveal his confusion.

‘The bird that flies into a crocodile’s mouth to help itself to a free meal. Plaque and scraps. There are snitches like him on every floor, trying to buy their way out early, that’s all. Probably knows you’re an addict and is waiting for you to slip up. I suggest you don’t.’

‘Slip up?’

‘Don’t go offering cash to the wrong people. Don’t visit the wrong cells. And don’t ask for anything you’re not gonna get.’

Fairchild stares at his knees and nods. His eyes are spinning in his sockets like marbles on the floor. Addicts suffer the most in here; you can train your brain, but the body will never listen.

‘I heard about the escape,’ Fairchild says.

‘You call that an escape?’

‘They say she was the first to ever get out.’

I turn to Fairchild and give him the look that teachers give their kids when they want them to listen. ‘When I was a kid, all I wanted was to get off this island. Travel, you know, find some place better. But it didn’t happen. My dad cheated on my mum, then a little later he choked on his vomit, for extra points. I could’ve left after that, with my mum. I could’ve left this place behind, started anew.’

Fairchild shrugs. ‘So why didn’t you?’

‘Because no one really wants to escape. Song Ye-jin spent months digging a hole in her cell just so she could fly. You ever heard of purgatory? People say that this island’s like purgatory. Get out of The Heights and you’re still not free.’

Fairchild leans his head against the wall and we sit in silence; sucking at the cold stone walls.

‘So what do you want now?’ Fairchild asks.

I stand up nice and slow and stare out the window.

‘I’ve spent ten years with my head down so I can get out of this cell. To everyone else this city might be a shithole, but they don’t see what I see.’

Everything in sight is grey. Scooters zoom by, heading for the harbour or the belly of the Rivers. One or two already have their lights on. The lights glow pretty damn well, even from way up here. Night is coming.

‘What do I want? I wanna get the hell out of here and make up for lost time. And ten years is a hell of a long time.’

Jiko’s Ducati is red like her hair and if the body has ever been scratched or damaged, then the evidence is buried beneath untold layers of paint and polish. It’s a classic Bosozoku ride: the handlebars are pointed down for quick getaways through small spaces, a reminder of the days when cops only had biker gangs to worry about. There are stickers all over the fuel tank: a big Japanese flag in the centre, surrounded by the symbols of old gangs that disappeared long ago. When she revs, the motor purrs like a well-fed tiger, and we’re out of the pleasure quarter and into the belly of the Rivers before we hear the sirens.

‘It takes them a while,’ Jiko says. ‘The girls at the clubs hate the suits as much as I do. They just pretend they don’t see anything.’

It’s night and I’m free with nothing but wind in my face and endless open road. The lights of the Rivers blur into yellow and red and green, streaks that spit across the passing walls as we puncture clouds of stench-filled smoke. The night is waking up and Sonaya breathes again.

‘Nakata’s place still open?’ I ask Jiko. She nods and steers towards the Rivers’ scrawny northern veins. The roads are crocked and we slalom around a string of potholes; I get the feeling she’d sooner lose the flesh from her bones than scratch the paintwork on her bike. We pull over in a long corridor of fluorescent signs, a myriad of fire escapes feeding into one another, infinite wires and cables stringing the streets together. Jiko takes her time dismounting; her fingers gently caress the throttle, like a jockey sharing a tender moment with their horse after a race.

I lead Jiko through the unmarked door and down the stairs. The place hasn’t changed one bit. The old record player still sits behind the bar, black leather stretches across the furniture, and the air is thick with artificial smoke; like of those old speakeasies from back in the day when people knew what jazz was and cigarettes were legal. I can barely stand up straight without brushing my mane against a maze of shimmering orbs that hang from the ceiling. Two middle-aged women in modern hanbok are conspiring in one corner; in the other corner two boys are exploring each other’s necks.

‘You look terrible,’ Nakata says. She’s standing behind her marble bar, looking at me like I never left. Short black hair streaked with violet highlights and big black eyes like an owl wired on caffeine. She’s wearing a leather choker and a single earring that looks more like a wind chime. Her voice has a distinct flavour to it, like the kick of rich dark chocolate. ‘Where’s your ear?’

I lean against the bar and run a hand through my hair, which I’ve grown past my shoulders and left to matt and tangle. I shaved the side where I’m missing an ear; there’s no point losing your ear if no one can see it. ‘Must’ve misplaced it,’ I say. ‘How you been, Nakata?’

‘Better than you from the looks of it. I heard you were getting out. What are you drinking?’

‘I’ll take the house special.’ I glance at Jiko and she nods. ‘Two.’

We take the booth in the corner beneath a black-and-white photo of a man and his sax. The smoke machine is purring away and shooting misty clouds across the tables. Fats Domino is singing about a Blueberry Hill on Nakata’s old record player. She loves the old stuff that no one else remembers.

Nakata brings over two long glasses of muddy ale. I watch her as she places our drinks on the table, and as hard as she tries, she can’t keep those lips of hers straight, the corners sliding up before she turns away. Damn, I have been missed. Twenty-four hours ago I was still in The Heights, scratching a farewell into the wall of my cell, and now I’m in heaven. I raise my glass.

‘To Sonaya,’ I say.

‘To you,’ Jiko says.

Damn right. Me and Sonaya, the two most important things in my life. I’ll drink to that.

‘I didn’t think you’d actually try and find me,’ Jiko says.

‘I said I would, didn’t I?’

‘You think I was going to trust the word of a murderer?’

I raise my glass and let the foam caress my lips. ‘You shouldn’t have. It was stupid of you.’

Jiko shrugs. One of the boys in the corner squeals and we both look over, their fingers tightly interlocked and their beaming smiles oblivious to us strangers.

‘I’ve got good instincts,’ Jiko says. ‘I’ve thought about what happened a lot. Whether I did the right thing, and whether you’d pay me back. I guess I got my answers tonight. That pig could’ve killed me.’

‘It’s done now,’ I say. I don’t want things to get too mushy; I’ve got a reputation. ‘What were you doing in that place, anyway?’

‘We don’t make a lot of money in the bar.’

‘I’m not surprised. I’ve seen how those girls welcome customers. I went there looking for you and all I got was some bad lip and some even worse wine.’

Jiko smiles as though as I’ve given the bar a five-star review. ‘Ume said she met you in The Heights. She’s got some big things planned and she seems to think you’ll help us out. That’s why she sent me in there to do you a favour.’

‘Where is Ume? We’ve got a conversation to finish.’

Jiko shakes her head. ‘Busy. The Homework Clubs are just the start, full of the wrong kind of men, and the unfortunate kind of girls. We’re gonna get them girls out of those clubs one day. One day soon.’

I watch as she glugs her ale even faster than me. A cloud of smoke passes across her face.

‘What have you got against the Homework Clubs?’ I ask. ‘I can think of worse places.’

Out of nowhere several wrinkles appear on her forehead.

‘You were at the wine bar. What did you think of those girls?’

I shrug. ‘They looked angry. Same way all girls do when they wear too much eye shadow.’

‘All of those girls did time in the Homework Clubs, and some of us have done time in places even worse. We’re the ones who got out. The ones who are gonna change things.’

She doesn’t look at me as she gulps down more of her beer. She doesn’t care what I think, and she’s probably right not to. Nakata ventures out from behind the bar and tells the boys to keep things clean. The women in hanbok are staring into ancient compact mirrors and touching up their makeup for men who might never show up.

‘What happened to you?’ I ask.

Jiko shakes her head and pushes her chin out. ‘What do you care?’

‘Maybe I don’t, but if Ume thinks I can be of use, I’d better know who I’m working with.’

She gives me the once over, her eyes a burnt mahogany that fades into speckled walnut toward their centre, a stark contrast to the black of her pupils. When they finally stop scanning, they settle on a point three inches above my left shoulder.

‘When I was a kid, I used to wake up to the sound of my father beating my mother. Sometimes he beat me too. Then one day he got a gun and shot her dead. Blew his own brains out shortly after. If I was at home, he would’ve killed me too.’

She pauses to drink more of her beer, closing her eyes to savour the taste, or force her father out of her mind.

‘I was recruited by Fumiko, same as the other street girls. She taught me how to take care of myself, and a hell of a lot more. Not a lot of girls’ escape Fumiko’s hand, but I did, along with a few others. We’re gonna be the ones to break her fingers and make her pay.’

I finish my drink and signal Nakata for two more.

‘I need to speak to Ume,’ I say again.

Jiko nods me away like I’m her nagging mother. ‘Yeah yeah, just wait, all right? I told you she’s busy. You seen Fairchild since you got out?’

‘Not yet.’

‘You haven’t forgotten about—’

‘No, I haven’t forgotten.’

I’ve got a place in the Rivers. A gift from Kosuke til I get back on my feet. A small attic room above a boarding house that gets a lot of male visitors in the night. Dust throughout and a smeared window that looks out over crummy streets full of second-rate singing rooms. It’s a damn palace compared to my cell on the sixty-third, but I’m not sleeping there tonight. Jiko drinks well, but she also drinks fast. Once we’re done, she can barely get her key in the ignition. I’m not gonna let her kill herself so soon after I saved her life.

I grip the throttle and give it a sharp twist as Jiko rests her head on my back. It’s gone three a.m. and I’m no monk myself; we sucked Nakata’s barrels dry. I guide the Ducati through the back streets north of The Cross, the motor humming and forming off-key harmonies with the retching of sewer drunks and sudden bursts of synthetic music. Every rotten molecule of this city whispers a million memories into my lonely ear; I suck it up like a starved cat licking milk off a bottle cap.

I get Jiko back to her flat above the wine bar. The lights are off and none of the other girls are around, so I support her up the stairs. It’s not a bad little squat for one person; four solid walls to herself, which is already more than most people. She tells me to stay and I’m in no state to argue. She switches the lights off and falls asleep fully clothed on the futon.

I stand at the window and enjoy the blissful throb of ale as it washes away the cobwebs from the dormant ventricles of my brain. The leftover scraps of the downtown party score the streets; scooters burst towards home, dissonant surges of passion erupt and echo, drunken arguments crescendo and fade away. Through a crack between concrete blocks I watch the bent-backed figure of a man as he sways and stumbles along the street, turns his head dumbly and stares at something out of sight. Eventually he trundles off, searching for a way out of the maze.

I make a pillow out of my shirt and lie down a few feet away from Jiko. My eyes have adjusted to the dark; even with her vest on, I can see more of her Rising Sun tattoo than I’ve any right to. I throw a blanket over her and she squints at me through one eye.

‘One day soon,’ she mumbles.

I put my hands behind my head and look up into the darkness.

Dust, and lots of it. That’s how I like my digs. Slanted roof, a window scrubbed clean with sandpaper, moth-eaten armchairs and lumpy mattresses and lacerated naked floorboards. Perfect. The attic belonged to a local artist who went mad and killed herself, and I’m the first to move in since it happened. But it doesn’t bother me. If ghosts exist, I’ll greet them gladly. Quiet company is my favourite kind.

Kosuke’s provided the bare necessities: a kettle with rust wounds, an ancient rice cooker with a splintered lid, a fridge half-stocked with basic greens, and crates of instant noodles. There’s a pile of new underwear in the cupboard and a selection of creased shirts and trousers sagging on metal hangers. Not my style, but I’ve got time to replenish.

I head down to the basement liquor store beneath the greasy dumpling joint on the corner and pick up a few essentials. The toothless old lizard behind the counter fills a cardboard box with my bottles and squints as he punches in the prices. whisky, brandy, gin, soju, sake, rum, I don’t care, as long as there’s a good supply of booze when I need it.

‘Hosting a party, are you, son?’ he asks, counting the notes I pass over. For a moment I think he’s gonna ask me for ID.

‘Yes, sir,’ I say, hauling up the box. ‘I just don’t know who’s coming yet.’

My first nights are as quiet as expected. There’s a young couple below who go at it all night, first shouting of one kind and then shouting of another. I don’t have much by way of entertainment, so I listen and sit with my bottles by the window, staring out at the vast grey towers of the Rivers. I’m up all night, leaving the attic only to yellow the floors of the shared bathroom. I don’t get a wink of sleep, and soon enough, I stop trying.

I lie awake thinking about the difference between the walls of this attic and the walls of my cell. I add it up every way I can, and the only conclusion I arrive at is that now I’m free to go anywhere I want, drink anything I want, see anyone I want. That might sound good to a man stuck in a cell, but after several bottles of booze, you remember that your favourite company is already inside your own head, and the difference doesn’t seem so big after all. All I have to cling to is a vague thread of a thought. It’s the same little creature that’s been knitting away at the back of my brain since day one in The Heights. My business with Jiko is settled, but there’s one more woman I have to see.