Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

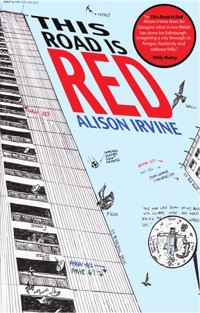

Spanning the five decades since they were built up out of the cabbage fields, This Road is Red is a novel about the thousands of residents who have lived there. Each of their lives are linked to another by a character, an incident or a place with lives overlapping and connecting in a mixture of drama and domesticity. There is a fire, a suicide, a birth, a marriage, a death and a near-death. A couple of ghosts, several fights, a handful of jellies and an overdose. The book is a record of how the events of the last five decades have impacted on a community.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 454

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

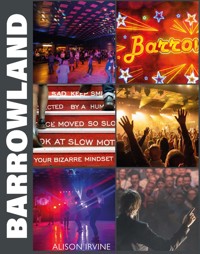

ALISON IRVINE was born in London to Antipodean parents. She was brought up in London and Essex and moved to Glasgow in 2005 to study an MLitt in Creative Writing at Glasgow Univer sity. She graduated with distinction in 2006 and since then her writing has been published in a variety of magazines and in an anthology of Glasgow writing, Outside of a Dog. In 2007 she was awarded a Scottish Arts Council New Writer’s Bursary. This Road is Red is her first novel and was developed through her close association with Glasgow Life’s Red Road Flats Cultural Project.

She lives in Glasgow with her family.

A Word from the Red Road Flats Cultural Project.

Glasgow Housing Association (GHA) and Glasgow Life created a partnership in 2008 to develop and deliver a range of historical and art programmes for current and former residents of Red Road and the surrounding neighbourhoods to commemorate the end of an era in Glasgow’s history.

As much of Red Road’s significance is attributed to its size, the programmes undertaken have focused on people’s memories, stories and photographs.

The aim of the project is to capture the full story of Red Road’s fifty-year life. We hope this book will help keep Red Road alive for years to come.

Details of the full range of projects which have been delivered and are in progress are available at www.redroadflats.org.uk.

First published 2011

ISBN : 978-1-910324-62-2

Published by Luath Press in association with

The paper used in this book is neutral sized and recyclable.

It is made from elemental chlorine free pulps sourced from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by

CPI Bookmarque, Croydon CRO 4TD

Typeset in 10.5 point Sabon

by 3btype.com

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Alison Irvine 2011

For Eddie

In memory of John McNally,resident of the Red Road Flats 1969–2009

Contents

Acknowledgements

Prologue

Section One

Section Two

Section Three

Section Four

Section Five

Section Six

Epilogue

Afterword

Acknowledgements

THE BOOK WOULD NOT have been possible without the generosity of the people I interviewed. Their time, their enthusiasm for the project and their willingness to go over the tiny details of their experiences gave me such rich material to work with. Thank you so much. You have made writing this book an abso lute pleasure:

Beki

June Aird

Matt Barr

Mojgan Behkar

Jim Bonner

Louise Christie

Sara Farrukh

Jahanzeb Farrukh

Derek Fowler

Ruvinbo Gombedza

Aysha Iqbal

Azam Khan

Veronica Low

Willy Maley

Jim McAveety

Helen McDermott

Sharon McDermott

Billy McDonald

Peter McDonald

Jean McGeough

Finlay McKay

John McNally

Frank Miller

Ntombi Ngwenya

Bob Niven

Thomas Plunkett

Marie Quinn

Grant Richmond

Donna Taylor

Iseult Timmermans

And the young people from Impact Arts’ Gallery 37: Ibrahim, Christian, Heder, Rahel, Ibrahim and James.

Thank you also to Bash Khan, Johnny McBrier, James Muir, Lindsay Perth, Remzije Sherifi, Eulalia Stewart, Kate Tough, Impact Arts, the Scottish Refugee Council, members of the Red Road Flats Project Steering Group, and Glasgow Life’s Martin Wright, Ruth Wright and the rest of the team. Thanks to Glasgow Housing Association for funding the project. Particular thanks to Jonny Howes from Glasgow Life whose support has been invaluable.

Thank you to Gavin MacDougall, Christine Wilson and their colleagues at Luath Press, and to Mitch Miller who illustrated the book.

Lastly, thank you to all my family: especially to Linda, Luke and Sammy Byrne, and of course to Arlene and Isla. To Eddie, thank you for everything. I couldn’t have done this without you.

Prologue

1964–1969

A MAN WITH A strong back and muscles thumbs braces over his shoulders, then sits to tie black boots. He stands at the sink and drinks tea with milk and sugar. Tunes the radio to fiddle music. Butters bread, cuts cheese and makes his piece. Finds his silver piece tin and puts his piece inside. Pours boiling water over tea leaves in a flask. Combs Bay Rum through his hair.

A pile of library books on the table. A basin under the table for later, to steep his feet. His wakening household. Children; nine of them, shifting in their shared beds. A son, the youngest, waiting at the kitchen door to make his breakfast and retune the radio. Bunnet. Coat. Piece tin and flask. Out the door. His son takes over the kitchen.

The man walks to Red Road. Mud and cabbage fields. Wet and wind and rain. The steel hanging off cranes. The gangs assembling. A day’s work. Years’ work. For him and for the trades. Good money.

Eating his piece and a young one sits next to him, tells him he’s not happy because he’s working overtime and not getting as much as his pal in another gang. You’ll get your bonus, don’t fash, the man says and takes it upon himself to have a word with the ganger.

Every day, the walk in his hard boots through Possil to Red Road. The steel frame rising, fixed at the joints by men with balance and nerve. The man going up in a hoist. Using muscles honed laying sleepers at Cowlairs. Hup hup hup. They get their bonus.

Twenty floors up. Someone lights a fire to fend off the freezing cold. Someone else tells him to put it out or they’ll all get sent down the road. Men not expecting their legs to sway with fear, looking down at the mud and the kit and the huts.

The man sees Arran on the clearest day yet. Its blue-grey bulk at the far side of the sky. The Clyde and the shipyards. Grit and glitter. It’s shipyard steel they’re building with. Sand and gold on the Campsie Fells. The men stop work to look, take bunnets off and wipe foreheads.

In summer eight students and their teacher come from Barmulloch College, go up in the hoist, learn about sway in tall buildings. Hold a plumb line and see that the steel structure sways. Can’t feel it but see the line move so believe it. The man feels it when they clad the steel, and the wind bullies the blocks, unable to get through anymore. Oh, then they sway.

More disputes. The men hear of another gang on more overtime. They’re not trades, he and these men, they’re the lowest paid and he will not have them exploited. He’s a union man, a fighter for the left. Don’t fash he says to the young ones.

They stop work for the opening of Ten Red Road. Thirty floors of four-room apartments. Ceremonies, plaudits, photographs. Ballots and excitement. Firemen doubling up as removal men and pulling up with people’s furniture.

Then on with Thirty-three Petershill Drive. Newspapers tell of overspend and high costs. It’s work though, for locals and those who move into the area, turning up with skills and strength. Working six or seven days a week, like the man, for his wife and his weans.

Late May 1967 and the boy waits for his father. The street is empty of boys and footballs. Everyone’s inside. The man works overtime and checks his watch. He’s too high up to hear cheers or roars from television sets. It’s on his mind as he works. They stop in time to run to Springburn and stand outside Rediffusion. Black and white televisions in the window show the match in Lisbon. He stands with other labourers and they watch the second half from the pavement, looking in at the televisions. At the final whistle their arms raise above their heads and the man sees the smiles of the fans in the crowd and the smiles of the players and their own smiles reflected in the shop’s window. Come for a drink, his workmates say, and he says no, he doesn’t care to drink anymore and he walks home happy. He finds his boy celebrating out the back and stands among triumphant neighbours watching wee ones go wild.

His wash at the sink is pleasurable and slow. Champions. All day labouring, all day thinking about the game. He pours water from the kettle into the basin, tops it up with cold. Moves a chair. Sits. His boy watches as he unlaces his hard boots and rolls each sock down an ankle and foot. He puts his feet in the basin and the boy tunes the radio to Sanderson and Crampsey. A plate of food, kept warm, a quick sleep and the next day is work and some of the boys are tired from celebrating.

The man is sixty years old. He labours on all the buildings. Is there till the last in 1969. He builds the concrete castle for the weans and the paths that go from building to building. Low walls. Grass. A place where the shops will be. Full classes and overspills in the primary schools. More schools needing built. The last of the trades come in to do their jobs. Tenants move in and the workers move out. Red Road. He built the highest towers in Europe.

His son views the flats as he walks with his siblings in a line behind his father and he thinks of the Yellow Brick Road. Likes them. Sleek. Space age. Mammoth. Rid Road says his mother. Red Road. His father’s last workplace. Red Road. Houses for thousands.

Section One

May 1966

SHE WATCHED AS THE towers grew larger. Her boy played with the frayed seat-top in front of him. The bus slowed at every stop and people took an age to get on and off. She would cry, she swore, if they’d run out of houses and she had to go back to the Calton.

The buildings were shocking. Massive. Some finished, with sleek sides and neat rows of windows, others with their insides exposed, dark as engines. Half-finished cladding. Cranes hanging over the tops. Scaffolding. The noise of the construction was exhilarating.

‘Ma, Ma, look up, they’re falling!’

May pulled her son’s arm and told him they didn’t have time to stop but she glanced at the tumbling clouds at the tops of the towers and knew what he meant.

It seemed like the whole of Glasgow was in the foyer of one-eight-three Petershill Drive. Shouts and laughter and hand claps.

‘Are they nice?’ May said to someone, anyone.

‘Brand new.’

‘What did you get?’

‘Twenty-two floor. Number four.’ The woman’s face was full and freckled. She smiled.

Her man dangled a key from his thumb and forefinger then snapped his fist around it. He wore a suit. His smile was huge.

‘It’s something else.’ The woman touched May on the shoulder. ‘The most beautiful house I’ve ever seen.’

‘Come on, son.’

May didn’t care what she got but she had to get something.

The man at the desk sat like Santa. He clicked a pen with his thumb.

‘What do I do?’

‘Put your hand in and take a piece of paper.’

‘Are there any left?’

‘Oh, aye, plenty.’

May stopped. It was too much. She couldn’t believe it could happen. The police, the Corporation, they said they’d help her get away and here she was about to get her new start. He’ll find me. He’ll chase me all the way to Red Road. He’ll wreck it. She didn’t deserve this, one of these immaculate houses.

The man waved his hand over the ballot box and said, ‘On you go.’

Yes, she bloody did deserve it.

Eyes closed, she put in her hand and felt for a slip of paper.

‘What have we got, what have we got?’ Her son jumped up to look at the piece of paper.

‘Fifteen/three, that’s what we’ve got,’ she said to her son. ‘Fifteen/three.’

‘Is that a good one?’

‘Oh aye, son, that’s a good one.’

‘Now, some folk have been swapping their houses if they’d prefer something higher up or lower down, and that’s fine,’ the man said.

‘Oh no. I won’t be swapping my house.’

She handed the piece of paper to the man who wrote her name and house number in a ledger and gave her a set of keys. An elderly couple leaning on sticks stood behind her. May turned around and held her keys out to them, just as the man in the suit had done to her.

‘I’ve got my house.’

‘Well done, hen, that’s smashing.’

‘On you go up in the lift,’ the man behind the desk said.

‘Which one?’

‘Either. They both go up and they both go down.’

May took her son’s hand and stood proudly by the lift, looking at the painted walls and the sparkling ceiling and floor. She tapped her fingers against his.

‘Calm down, Ma,’ her son said.

‘I can’t help it.’

The lift was full of people when the doors opened. They seemed like her kind of people, happy and friendly and the folk that squeezed in with them seemed like her kind of people too, one man taking all the orders for the floors, pressing the buttons and calling out mind the doors.

It was the cleanest, most amazing house she had ever seen, with a view out over the Broomfield. All fields and grass. Gorgeous. A bathroom inside the house with basin, toilet, bath. A kitchen with spotless cupboards, an electric cooker and oven. A living room, two bedrooms, a veranda off one of the bedrooms and another room with no windows but big enough for something – what? – she barely had anything to fill the house with. It opened out, bare and lit and freshly painted, in front of her. She would work to fill the house with furniture and rugs and crockery and toys. She would work to pay the high rent. By God, she would work. She took off her coat. Where to start? And that’s when she cried, finally, knowing they were safe.

Jim 1966

Each day as Jim passed he used to see the men at work boring the fields by Red Road. He knew something was going to happen. Each day on their way along the road to the Provan Gasworks he and his wife, who worked at the gasworks too, saw the men and noted the small developments; the ground levelled, the surplus earth pushed into heaps, the concrete mixers, diggers and cranes, the workmen’s huts, until eventually it was all steel, steel, steel. Then, Jim and his wife realised that something big was taking place, something mammoth.

Jim worked hard; the gaffer of the labouring squad at the gasworks. When the industry moved from old coal to oil, the foreign gas, he was there, in charge of his squad. The catalyst squad. The pick and shovel days were away and it was chemicals they used now. Cleaner, safer. Jim took his job seriously.

It was his wife who said to him shall we try for a house in the Red Road Flats and because it would be handy for work, Jim said, aye, why not. The older children married or working away. Just the younger two under the roof. The bairnies.

Twenty-eight/four. Ten Red Road. A view to the west and a glimpse of the Arran hills on the clearest of days. High enough to see whole sunsets spread like syrup across the sky.

Matt Barr

I was nine when we moved there. My first memories were my dad trying to describe an electric fire. It was fitted on the wall in the living room. We came from Springburn, a room and kitchen up a close with an outside toilet on the landing. My mum and dad slept in the kitchen in a wee in-shot where there was a double bed and then you went through a lobby and there was a big front room which was like a general purpose room but we had a big double bed in it and all three brothers slept in the same bed together. It was a godsend to move to a beautiful brand-new house. I remember when we moved in they were still actually building all the other blocks and there was a big fence that ran all the way round the building site. I remember there was nothing to do, no playgrounds, no amenities. So we played in the building works a lot. We were always getting chased by watchmen. We were quite young. We never did anything bad.

Jennifer 1966

They went for a walk. To get to know the area, her father said, and her mother spent a wee while at the mirror fixing her hair. Her father kissed her mother’s neck. Jennifer and her brother wore their chapel shoes and their granny’s knitted jumpers underneath their winter coats. Their mother tilted their faces to her and patted their heads before they left the house. The lift shook its way to the ground.

‘Where are we going?’ Jennifer said, because the day felt like an event.

‘Where the wind blows,’ her father said.

When they walked through the canopy by the foyer doors the wind did blow, swirling construction-site dust and debris at their feet. Jennifer and her mother nearly toppled and their coats flapped open to their bottom buttons. The family stepped out from the canopy where the wind was still cold but less charged.

Around them noise from the construction site was loud. They walked through frozen mud tracks and stood by the perimeter fence of the new long block and listened to the clangs and chips and thuds of the workmen inside.

‘What I would like to do is get a loaf of bread,’ Jennifer’s mother said and they looked for a shop.

‘That’s where they’ll build the shops,’ her father said.

‘No good to me at the moment.’

‘Will we walk to Springburn? Or the ones at the top of the road?’

‘We’ll have to.’

But they didn’t walk yet. Instead they looked up at the building in which they lived and their father told them to count down three rows of windows from the top. Twenty-eight, Ten Red Road Court. Flat four.

‘It hurts my neck to look,’ Jennifer said.

At the very top of the building strips of cladding met in a pinch, not quite a point, and the windows thinned to black lines.

Her father curved his hands above his eyes. ‘What an idea. The audacity of those men. Colleen, did you ever think we’d be living twenty-eight up in a brand-new multi-storey?’

‘No, I did not. If they built some shops, this place would be perfect.’

They stood, the family, in the cold wind and waved at the men and women and weans standing at other windows, eager and open and smiling.

‘Where can we play?’ Jennifer said.

Her mother and father looked about them at the workmen’s huts and cranes and scaffolding.

‘You can take a skipping rope or your balls and play outside the building,’ her mother said and although there were no swings or slides, Jennifer thought that Red Road – the half-built buildings, the fields, the dips and ditches – was the most exciting place she’d ever seen.

‘Jim, these weans will bring mud into the house every time they come in,’ Jennifer’s mother said. ‘To think I scrubbed the Possil house from top to bottom to make them let us live here.’

‘It worked. You did good. We’re here,’ Jennifer’s father said and he took his wife’s hand. ‘Handy for work, too.’

Davie 1966

He held onto the cold scaffolding and looked at the pile of sand that rose below him like a great grey wave. One more jump. The highest one yet. They’d given the night watchman the runaround then hidden until he’d walked away, thinking, perhaps, they’d finally gone to their beds. Not so, Mr Watchman. He knew his friends were waiting behind the fence with their booty – scaffolding bolts and wooden boards. He turned and gave them the A-OK finger circle and breathed in before he leapt.

It was supposed to be a silent jump, like the Commandos, but it wasn’t. He couldn’t.

‘Raaaah, oh oh oh rahhhh, ya beauty!’

He hooted and yelled and roared his beautiful drop to the sand. Sand covered him when he landed and he rolled, nothing in his ears but the scuff and rustle of his moving body, and when he lay in the sand, shoulders and head and arse half-buried, and breath coming out in laughs, he looked through the high scaffolding and felt extraordinary. The night fizzed, the clouds hung heavily.

Then he remembered the rats and sat up. Shouts.

‘Sorry Davie!’

‘Davie! Enemy!’

It was his pals, running away, the fence still jangling. Davie dragged his legs through the sand and was running to leap the fence when the night watchman’s torch dazzled him. Before he could bolt, the night watchman’s hand grabbed his arm and got him in a head hold. It hurt. He felt knuckles against his forehead.

‘Game over, son.’

Torchlight was in his eyes again. Sand in his mouth.

‘I’ll go quietly.’

‘You annoying wee prick.’

‘I was training.’

‘I’ve got a job to do.’

‘Don’t tell my da.’

‘Now that’s an idea. Right, you, out, and come with me.’

The night watchman straightened Davie up and gripped his neck, marching him to the gate. They walked to Thirty-three Petershill Drive. Davie wondered if his friends were hiding anywhere and he did some Commando hand signals in case they were but stopped when the night watchman told him to pack it in, you bammy bastard.

Nobody about. Warm lights in some of the houses. Davie wondered what his da would say. His brothers would laugh. They’d be able to laugh in safety now, because they had their own beds, unlike the other house, with the three of them in one bed and never knowing who was going to get skelped as well when his da came in to administer discipline.

‘I’m going to leave you here and watch you get in the lift and you’re going to go in your house and get into your bed and give me some peace. If I catch you out here again I promise you, your da will know about this.’

The night watchman pushed Davie through the door. Davie pressed the button for the lift and wiped sand off his knees. He snuck a look at the watchman and saw that he was shorter than he’d thought, and younger, and he looked a bit like his uncle John. He watched him put a cigarette between his lips and light up, flicking the match to the ground.

‘On you go,’ the night watchman said through smoke, and motioned towards the lift.

Without a word Davie returned to his house.

‘Did you do the jump?’ his brother asked, lifting his head off the pillow.

‘Aye. I flew.’

‘Did you get caught?’

Davie undid the catch on the window and leaned right out.

‘No way.’

He saw the night watchman down below, patrolling the piles of sand and scaffolding with the unmade tower reaching into the dark sky, and when the night watchman was away over the other side of the site, he saw the rats come out, odd random rats at first, darting and stopping and starting, and then a whole teeming load of them, crawling over everything, getting in about it, reclaiming the place and picking at the workmen’s pieces.

Jennifer 1966

Jennifer’s mother told the children to go out or stay in but not to play on the landing. Her children chose to go, the back stairs ringing with their heavy footsteps. We want to try these stairs, they said and she shouted after them to take care and mind they didn’t bring mud into the house when they returned.

Then Jennifer’s mother propped open her front door and collected up her neighbours’ doormats and her own. She put hot water in a bucket, added some Flash and took her mop from the cupboard. Downstairs in the foyer she’d seen a sign with the number four on it which meant it was her turn for washing the floor.

Flakes of mud and faint footsteps covered the floor. There was more dust and dirt in the rectangles where the doormats had lain. She swept first with a bristled brush and tipped the sweepings down the chute. Then she ran the mop over the mud, pushing it hard over the bits that had stuck to the tiles.

The woman from number three opened her door and told her to come in for a cup of tea after, if she had time, and Colleen said she would, even though there was the tea to be cooked and she was just in from her work herself. She used fresh water to clean the suds from the floor and then she used a dish towel to dry the floor. And while she had the mop and bucket out she did her own floors too. Then she went next door for a cup of tea and the women stood on the veranda with their cups in their hands and the wind in their faces, looking down at the weans and the workers coming home off the buses below.

Jean McGeogh

Aye, they were all going up, they were all getting built. There was a lot of noise but it was good. I loved the flats, I loved them. Great neighbours. Neighbours in a million they were. Really all working-class folk, you know, good, honest, and you could leave your door opened and anything.

Jennifer 1967

Jennifer’s father called the family into the living room. He told them to mind the pasting table and be careful of the dust cloth. Then he cast a hand in front of the red swirls on the wall and said, ‘See this, this wallpaper. It will outlast us. Outlive us. Put up by the hands of a master decorator. It’ll be up for the next fifty years.’

Jennifer’s mother ran her palm over the wall and said, ‘It’s very red.’

‘Do you like it?’

She smiled. ‘I love it. It’s just how I wanted it.’

Jennifer liked it too. The living room looked like the pages of her mother’s magazines. Hot and red and luscious; the swirls on the walls like the swirls on her dress.

‘Away and play,’ her mother and father said at the same time. Her father put his fingers through his hair and his hair stayed spiked. Jennifer and James grabbed their coats and shut the door behind them.

Outside, they ran across the mud to where the men were building the next tower. Steel and cranes and temporary floors way up the inside of the building. They found a sheet of plastic which James stabbed at with a stick. They saw asbestos. Jennifer picked up a piece then threw it to the ground. She found a better piece, good for drawing lines, and they ran back across the mud to the side of their block. James left her and went to talk to a boy on a bike. Jennifer marked her beds on the ground and threw her peever stone. Girls came along, including the girl from number three with pigtails, Jennifer’s neighbour. They played, taking their own stones from their peever tins, bending close to the ground as they drew more beds with more asbestos.

Her brother dragged a piece of wood and stamped on it, telling the girls he was breaking it into pieces for his crossbow. A girl they’d never seen before took two balls from her coat pocket and began to throw them against the wall. The others stopped to watch her as she chanted her rhyme and slapped at the balls and when there was nothing new to see they went back to their beds.

Jennifer’s mother at the very top of Ten Red Road with a basket of wet sheets, the wind swaying the washing lines and flicking the sheets into her face when she hangs them up. The sheets shifting and flapping. She’s holding pegs in her teeth and clipping a bedspread to the line. Her hair in her face, her dress with the swirls on it flat against her legs. Thick clouds and a white sky. Seagulls sit on the ledge that goes round the building. The ledge is as high as Jennifer’s mother’s shoulders. The very top of the flats. It’s exhilarating.

And Jennifer’s mother is proud of her family; her husband who she walks with every day to the gasworks in Provanmill where she cooks and he labours; her children who are well-mannered and doing great at school. The rent is a leap from the house in Possil, yes, ten pounds a month, and more than they paid for a quarter year in their old house. But they won’t want to move to Cumbernauld like their neighbours from across the landing. No thank you. They’re happy at Red Road.

They’re still building the flats. The work goes on and on. She’s at the centre of a new era. New housing. New Glasgow. She looks at the half-finished cladding on Ninety-three Petershill Drive. Semi-clothed. A trouser halfway up a leg. To the left of the building a boy crosses the wasteland. He scampers; leaping and veering and running. He wears shorts and a T-shirt with a collar. He carries a bag that hangs from his fist like a cartoon burglar’s sack. Strong legs. Windblown hair. She watches him run out of her view, behind the half-built tower. A scan of where he came from – the open ground and the railway – and then she picks up her washing basket and peg bag and goes back down the stair.

The boy ran straight at them, his sandshoes slapping on the concrete. Jennifer and the girls stopped their beds and waited for him to go away. James looked up from where he sat on the ground, nailing his pieces of wood into a cross shape. He stared at the older boy. The older boy stopped and panted, a lick of fringe falling below one eyebrow, his bag hanging from one hand.

‘Are you making a crossbow?’

‘Aye.’

‘For hunting rats?’

‘Maybe.’

One of the girls threw her stone and hopped over her beds.

‘What’s in your bag?’ James said.

Something in the bag jerked and scrabbled. The boy held the bag out in front of him, his fist gripped tightly around it.

‘Guess,’ the boy said.

James stared.

‘A ferret,’ Jennifer said.

‘How did you know?’

‘I seen another boy with a ferret in a bag.’

‘Who?’

‘Kenneth Campbell.’

‘I don’t know him.’

‘Well he had a ferret too. What’s your name?’

‘Davie. Did you see the ferret?’

‘No.’

‘Do you want to see this?’

‘Aye.’

The girls held their stones, James stood up and the girl with the balls stopped playing. Davie smiled. He had the beginnings of an Adam’s apple in his throat and hair that hung loose around his ears and neck. He held the bag in the crook of one elbow and slipped a hand in. His wrist came out first and then he lifted out the ferret. Davie dropped the bag and put his other hand on the ferret, bringing it close to his body. The children stepped in to look and the ferret twitched and struggled, its back and sides moving as it breathed.

‘Ah it’s so cute!’ one of the girls said.

‘Does it bite?’ said Jennifer.

‘Yes.’

The girl with the balls ran away.

‘Where did you find it?’ James asked.

‘By the railway.’

‘How did you catch it?’

‘Jumped it.’

Eyes raised from the ferret to Davie’s face to the ferret again.

‘What will you do with it?’

‘Play with it, then let it go.’

The children took a turn at stroking the ferret’s fur. Its eyes didn’t stop moving.

Davie said, ‘I’m going to let it go now.’

‘You didn’t keep it for long,’ said one of the girls.

‘I can catch another one, easy. Pass me that bag.’

James picked up the bag and held it out to Davie who took it and released the ferret. Then he turned and walked away. James stared after him. The girls stared too.

‘He’s my big brother’s pal,’ one of them said.

James picked up his crossbow, left his sister and her pals, and went after Davie.

Davie and some big boys kicked stones as they walked, in no particular hurry and in no particular direction. They grabbed at things they found on the ground, hurling them in the air. One picked up an empty ginger bottle and swung it from a finger. Another pulled his arms out of his jumper, stretched it over his head and tied it around his waist. James watched Davie drag a piece of wood along the side of a wall, then step on the wood and snap it, the bag with the ferret gone. The boy’s jumper slipped off his waist and fell on the mud. James was about to shout after them but they ran, suddenly, and James had to run too. He stopped at the jumper, picked it up and followed the boys into the foyer of his own building, Ten Red Road. They got in the lift.

‘That’s my jumper,’ one of the boys said.

‘I came to give it to you.’ James held out the jumper and the boy took it.

‘Cheers wee man.’ The boy sniffed like a grown up.

James looked up at the big boys. They chewed sweets with wet lips and leaned against the walls of the lift.

‘What will we do?’ one of them said. ‘Play in the lift or chap door run away?’

There was the sound of the foyer door opening.

‘Quick!’ Davie pressed a button and the doors closed. ‘You choose, wee man,’ he said.

James didn’t like being stuck in the lift. It had happened once before with his sister so he said, ‘Chap door run away.’

The lift went up and one of the boys said they’d start at the top and work down. Oh mammy daddy, he had heard about the boys and girls who played chap door run away. He wanted to go home. He didn’t want to go home. He looked up at Davie who patted his shoulder.

‘It’s all right, pal. Stick with me. Best to plank your cross-bow somewhere.’

So James leaned the piece of wood against the side of the lift and waited. One of the boys took a length of wool from his pocket and wound it round his fingers.

The lift stopped at floor thirty and the boys got out. The boy with the wool tiptoed to one of the doors and tied one end of the length of wool to the door handle. All the boys began to giggle, bending over and holding their hands over their mouths, big eyes looking around, a trickle of snorts and squeaks and inhalation. Tiptoes and bent backs.

‘Hurry up,’ one said. His voice was a whisper.

Davie took hold of the other end of the wool and began to stretch it across the landing but footsteps sounded from behind one of the doors and the boys ran into each other, wild and feverish. A key unlocking a lock. About to get caught. They fled out of the landing door, the boy yanking the wool free from the door handle, onto the stairs, running down them fast, each boy running a few steps then putting a hand on the banisters and jumping the rest. Three floors down they stood in the stairwell with the door to the twenty-seventh floor ajar. James stood with his head down, breathing fast, and smiling.

‘Okay, this one,’ the boy with the wool said.

James knew his downstairs neighbours but he didn’t say anything.

They were better organised this time; swifter, less gangly about their work. Doors one and four were opposite each other. The boy with the wool stood outside door one and tied the wool around the door handle. Then, with Davie standing by him, he stretched the wool across the landing to door four and tied the wool to door four’s handle. He checked the wool which was taut and checked the knots which were strong. A boy stood by one door and Davie stood by the other. James watched their hand signals; one, two, three. He knew it was going to happen but he wasn’t prepared for the noise of the knocking and the charge towards him as the boys ran for the door. James was first down the stairs, hooting and sucking in his lips; he even jumped the last three steps, but when he looked back, the boys weren’t following. They were bunched by the door, motionless. One turned to James and scowled. Davie put his finger to his lips and beckoned for James to come back up.

‘Listen,’ he said.

Footsteps.

‘Hold on please,’ said a woman’s voice. It was Mrs Cameron, his mother’s friend.

Scuffling and scratching. ‘Hello?’

The first tug on the wool and all the boys nearly collapsed, holding their stomachs, bunching fists into their mouths. James giggled. The wool tightened as the woman pulled her door but couldn’t open it.

‘My door’s jammed,’ she said. ‘Who’s out there?’

The door rattled on the other side now. Big tough tugs that made Mrs Cameron’s door click shut.

A man’s voice. ‘What’s going on here?’

The boys looked towards the door with the big voice behind it. The wool stretched across the landing. Mrs Cameron’s voice again, ‘Harry, is that you?’ Her letterbox open and her voice coming out of it.

‘I can’t stop laughing.’

‘Maggie, are you stuck too?’

‘I’m dying with laughter.’

‘I can’t open my door,’ she said.

‘She’s talking through her letter box!’

‘Neither can I.’

‘Something’s jammed. Can you give yours a tug, Harry?’

‘I’m trying.’

‘Tug it harder.’

‘I’m going to die laughing.’

‘Some wee bastards have tied our doors together.’

‘Oh my God, he’s going to break the wool.’

When the boys saw the man’s door lurch violently inwards and crash shut then lurch violently inwards again they ran down the stairs, floor after floor, silently, slowing up when they felt safe, until they walked nonchalantly onto a freshly cleaned landing where a pair of lift doors were opening, letting out a woman, James’s mother.

The older boys put their hands in their pockets and stepped aside to let James’s mother pass. Silence. Casual stances. Not a word was spoken except by James’s mother. ‘James, up the stair with me, please, after I give these messages to Alice.’

The boys put their heads down and stepped into the lift, Davie looking up once to wink at James, before getting in the lift himself.

‘Hey, wee man, do you want your crossbow?’ Davie shouted and held the crossbow between the doors.

‘No he does not,’ James’s mother said.

In the house she ran a bath then called down from the veranda for Jennifer. She dropped a sponge into the bathwater and tested the temperature with her fingers. James climbed in.

‘What were you doing with those older boys?’

James looked at her and thought before he spoke. His mother waited.

‘I don’t want to find out you’ve been terrorising our neighbours. These are good people we live among.’

‘One of the boys, Davie, he caught a ferret.’

‘Really? A live ferret?’

‘Aye. I stroked it.’

They talked about the ferret and his mother said, ‘As long as you don’t bring one in the house.’

When he thought it was safe, he bent his head and splashed water on his arms and chest and changed the subject.

‘Are you pleased with your wallpaper?’

‘Oh aye.’ She looked around the bathroom walls. ‘We’ll do in here next.’

James heard his sister come in.

‘I found your crossbow in the lift,’ she said and his mother shook her head and left the two of them in the bathroom, Jennifer sitting down to pee and laughing as James told her all about his time with the big boys.

Jennifer 1968

Jennifer watched the carpet. The wind got under it and made it billow like a sheet. She couldn’t tell how the wind got there because the carpet was fitted from wall to wall. She chased the ripple and slammed the heel of her hand onto the carpet as if she was catching a rat. The building swayed and the tassels on the lampshade shook. The sound of crashing pots and cutlery came from the kitchen.

‘Good God, some hurricane,’ Jennifer’s mother said. She stood by the window. ‘I hope they knew what they were doing when they built up this high.’

Her father stood up and joined her at the window. Jennifer stood up too and rested her chin and hands on the window sill.

‘They were built to sway a bit,’ he said.

‘A bit!’

Jennifer thought they could be at sea; her eleven-year-old hands holding onto the railing of some bulky ship, while the turbulent air heaved them one way and then the other. She looked down into the dark and saw shapes she thought might be sheets of plastic or sheets of newspaper or kit from the building sites thrown into the air or blown, twisting, onto Red Road.

‘And James is sleeping through this,’ her mother said.

They were quiet. Jennifer saw a patch of condensation form at the bottom of the window from where her breath stopped on the cold pane. She looked up at the reflection of her parents’ faces. Gentle.

And then the building shuddered and her father nearly fell on her and her mother screamed and the pots in the kitchen were at it again and the books on the shelf gave up on themselves. Jennifer gripped the window ledge. Her father said sorry hen, and her mother said right, who’s coming? She took the blanket that lay on the settee, slung it over one shoulder and tucked a couple of cushions under her arm. ‘Jennifer?’

‘I’ll stay and mind James,’ her father said.

Jennifer and her mother caught the lift downstairs and stepped into the foyer where other neighbours had gathered. Mrs McCluskey, Lizzy and Harry from down the stair, Mr and Mrs Fine; everyone from the high up floors. One old woman sat asleep on a chair.

‘Terra firma,’ her mother said and she sat Jennifer down and told her to put her head on the cushion and get under the blanket and sleep, which Jennifer did, but she couldn’t sleep. She keeked at the men in their pyjamas and the women with their curlers and knitting, and listened to the chat. Moans, jokes, remarks – they were familiar voices and they all said they wouldn’t be going back up the stair until the hurricane passed on. Each time the lift doors opened the talking stopped and the heads turned and the new refugees were greeted with catcalls and comments. Jennifer stared at the legs of every one around her until her mother woke her in the middle of the night and heaved her up to join the others, standing and shaking themselves in their slippered feet; washed up debris on a storm-shattered beach.

Betty 1968

Betty put on her housecoat and got her man out the door with his piece and flask and straightened tie. When she closed the door she looked over her house with her ferocious eye, straightening the pictures in the hall and picking up the envelopes and papers that had slipped from the wee table. Her tea cups had shuddered on their saucers but the china on the sideboard was intact. Not so the Aynsley ladies who had toppled from their glass shelf in the display cabinet; the door had sprung open and a bouquet of flowers and tiny hand were lying on the carpet. She couldn’t bear to look.

Outside, Red Road lay bruised and swollen: flattened grass on the fields, trees down, a car on its side. Wreckage everywhere. A lump of steel stuck into the side of one of the unfinished buildings. More steel lay thrust into the ground.

She would start with the landing floor, work from the outside in, and get her house straightened and correct. On the way to the mop and bucket and Zoflora she picked up her poor wee ladies and put their broken parts into a dish for Douglas to deal with when he returned from work. At least the swaying had stopped.

Opening the door to the landing, she set the bucket down on the lino.

‘Douglas!’

Her husband sat on the landing, his back against the wall, knees bent, head lolling onto his right shoulder.

‘Douglas, what are you doing?’

He didn’t move or answer.

‘Douglas?’

She rattled the mop against the bucket and was just about to rattle his arse when he started. Thank God he wasn’t dead.

‘Douglas, look at you!’

He held his hands out in front of him as if fighting off an attacker. ‘I’m waiting for the lift.’

‘No, you’re not, you’re asleep. Get up.’

It had been a terrible night. Douglas had sat up in bed for most of it, facing the wall above the bedstead, his hands and forehead pressed against it, moaning at every clash and clink outside. Betty had seen the night through with a few wee halfs but Douglas didn’t touch anything because he said he’d be sick if he moved away from the wall.

‘Oh my wee darling,’ Betty said, softening, and helped him up. ‘Will we get you in the lift before you get the sack and we get thrown out of our new house?’

‘You can take on a few more cleaning jobs if I get the sack,’ Douglas said. There was nothing wrong with him.

He stretched as he stood and picked up his briefcase and umbrella. He pressed the lift button.

‘I’m cleaning away over in Knightswood today, as a matter of fact,’ Betty said. ‘I’ll have the tea in the slow cooker.’

‘Ach, that’s why I fell asleep,’ Douglas said. ‘Look, Betty, the lifts aren’t working.’

One of the lifts jerked itself down to their floor. Knocking and shouts. Young voices. Scuffling.

‘Let us out,’ they heard someone say.

‘We’ve been stuck between floors. Will you get the doors open for us?’

Douglas put the point of his umbrella between the lift doors.

‘Take your jacket off,’ Betty said.

Douglas didn’t answer and levered the doors open with his jacket on.

A gaggle of uniformed children fell out onto the landing. They milled and fretted and hopped around and spoke in high voices.

‘Did you not hear us shouting?’ one boy said.

‘I was asleep, son.’

‘My sister slept through the whole hurricane.’

Douglas yawned. Betty looked at the children and noted areas for improvement. When it was clear that the other lift was stuck too she took matters into her own hands.

‘You can come through the house,’ she said, ‘and use the back stairs.’

It was the only way down if the lifts were broken.

‘Some storm,’ the boy said.

‘Yes, and mind your fingers on the walls.’ She led the way through the lobby and into the bedroom where she unbolted both doors and stood back to let the children pass.

‘Wait!’ she ordered. ‘Douglas, we can’t let these children out in the state they’re in.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with them.’

‘Shoes. Hair. Stains. This one’s face needs washing.’

The children looked up at the adults with pale, expectant faces, brylcremed quiffs and Alice bands. Beautiful shining eyes, the lot of them. Betty felt a tug inside herself, some shift towards sadness or serenity, it was hard to tell.

Her husband laid his briefcase on the bed and knelt in front of the open wardrobe. He leaned inside and pulled out a shoebox.

Betty ran out of the room and returned with a bowl, a flannel and a brush.

‘Line up!’ she said.

The children did as they were told, turning their heads to peek at the bowls of potpourri, the wedding picture on the chest of drawers, the poem in a frame – If, it began.

‘What’s that, a prayer?’ one wee boy said.

‘It’s a poem about how to live,’ Douglas said. ‘I’ll do their shoes first.’

He told the first child to sit on the bed.

They were silent as Douglas opened a tin of black polish, dipped the bristles of a wooden brush into it and began to scrub the shoe. He asked the child to straighten his leg and put his flexed foot into his hand and he did the back and sides and toe of the shoe and then he took a yellow cloth and shined up his work. He did the other shoe and the children and Betty watched. When he was done the boy stood up and looked down at his shoes.

‘Don’t you go splashing in any puddles,’ Douglas said. ‘They need to last you a wee while.’

‘I’ll take over from here,’ Betty said and she dipped a corner of the flannel into her bowl and wiped at a stain on the boy’s jumper. ‘What is that, toothpaste? Tut tut, wee man.’

‘At least I cleaned my teeth.’

‘Did you hear that? At least he cleaned his teeth. You’re right to clean your teeth son, or you’ll end up with wallies like me before you’re twenty-one.’

The children turned their faces towards Betty and she gave them a righteous closed-lip smile.

When the first boy was done, Betty patted him on the back and led him towards the doors to the back stairs. ‘On you go,’ she said, ‘and don’t tell your mammy or she’ll give me a row for interfering.’

Douglas and Betty worked their way through the line of children. Betty pulled up socks and washed mouths and noses, parted hair and put a brush through ponytails.

Douglas dipped into a tobacco tin and searched for a tiny screw which he held under the light by the window and twisted into the hinge of a wee girl’s glasses. He rolled the sticking plaster that he’d taken from the glasses between his thumb and forefinger and Betty held out her hand for it. ‘I’ll deal with that,’ she said and they looked at the girl who was missing a tooth but there was nothing they could do about that.

‘On you go,’ Betty said and they watched her turn and wave before she clomped down the back stairs.

‘You look handsome, Mr Meechan,’ she said and straightened his tie again.

‘Thank you, Mrs Meechan. Just imagine if we’d been allowed to…’

‘Stop. Don’t spoil it. You don’t make the rules.’

‘We could make good parents – ’

‘I know.’

She followed him to the back stairs and watched him go. He turned his head before he was out of sight and smiled.

‘Keep working hard,’ she said and went inside, bolting both doors and returning through her house to the landing where the mop stood in the bucket of water, now cold. She picked up the mats from outside her neighbours’ front doors and shook them. She gathered up her special mats – the ones she stepped on when she came out of the lifts to avoid spoiling the floor – and she leaned, for a second or two, to gather herself, letting herself imagine, briefly, tidily, how life could have been.

Jean McGeogh

Once we got in we discovered that there were no stairs off the lifts and if the lift broke down the kids they would be standing in the landing saying ‘shoosh, shoosh’. They had to go through your house to get onto the back stairs. And then, ‘we’ll miss school’ and I used to open the door and say ‘no yous won’t’ and they’d walk through and they’d be looking at the house and that and the wee ones would go (to my son) ‘oh I was in your house this morning.’ And maybe some of them did it themselves, I don’t know what they did but the lift would stop and the door would open and let them out and they’d be on the landing and I’d get up and say ‘come on, out through the house.’ Always they had to go through somebody’s house to get on the back stairs.

Jennifer 1969

Jennifer’s father rolled out the pastry to Elvis Presley. ‘Blue Suede Shoes’. The record player was brand new and the Elvis LP one of two long players he possessed. The other was The Dubliners. He turned up the volume as loud as acceptable for communal living in high flats with decent neighbours and opened the kitchen window. He liked to bake.

His wife was hanging out washing on the roof again – she’d become intrepid since moving to Red Road. With the other women, her friends now, they were like pioneers, making use of every bit of space, every facility, every aspect the flats had to offer. She was still unhappy with the lack of shops, however, and grateful for the vans that came by, parked up and sold everything. Dick’s was the orange van. Calder’s was the green. His wife sent the weans on errands on weekends and they came back loaded with messages for their mammy and their neighbours. His lovely wife. He’d been lucky to meet her at his age with four weans already under his belt. But she called herself a late starter and took on his children as if they were her own and asked Jim if he’d mind being a daddy all over again. Anything for you, hen. They’d worked hard in the old house, on top of each other, fighting for space. Now that they were in Red Road with the older weans moved out and moved on, he hoped life might be a bit easier for her. For them all.

He added cinnamon to the stewing apples and turned off the cooker. He took the paper from a bar of butter and ran it over a Pyrex dish. He rolled the pastry some more, palming the rolling pin to the pastry’s edges, flattening and smoothing the bumps. He’d floured the worktop and the sheet of pastry lifted a treat, dangling from his fingertips. He pushed it into the base of the pie dish, his fingers creating divots where the pastry met with the wall and the base of the dish. With a quick knife he cut off the pastry that hung over the sides of the dish, leaving some to spare. More flour on the worktop and the pastry rolled into a ball again then flattened. Elvis Presley played on.

They would eat the pie after they sat down for their tea and before the weans got washed. He couldn’t get over the state they returned home in. Mud in their hair, grass stains, dirt under their fingernails. He knew they were happy, but. His daughter with her Guides and Irish dancing, his son with his pals who ran about daft looking for ferrets and birds’ eggs.