Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

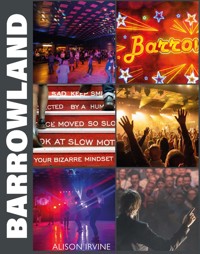

The Barrowland Ballroom – voted 'best music venue in the UK' by musicians and artists (Time Out) – has been a cornerstone of Glasgow's live music scene for decades, embodying the city's identity and spirit. In Barrowland: the inside story of Glasgow's beloved ballroom, Alison Irvine immerses readers in the tales of the individuals behind this iconic venue, from memorable gigs to backstage moments. It's a must-read for music lovers and anyone who treasures Glasgow's magic!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 417

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

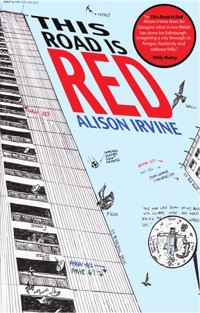

Photograph: Chris Leslie

ALISON IRVINE is the author of Cat Step and This Road is Red. Cat Step was a Guardian Readers Book of the Year, a BBC Radio 4 ‘Open Book’ Editor’s Choice and an iPaper Best Book for Christmas. This Road is Red was shortlisted for the Saltire First Book of the Year Award. Her creative non-fiction work was Highly Commended in Wigtown Book Festival’s Anne Brown Essay Prize. Alison has received several awards from Creative Scotland to support her writing and she is the writer in the artist collective Recollective alongside photographer Chris Leslie and illustrator Mitch Miller. Born in London to Antipodean parents, she lives in Glasgow with her family.

First published 2025

ISBN: 978-1-80425-328-1

Some of the text and images in this book first appeared in the limited-edition book Barrowland Ballads published in 2019 by Graphical House.

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 11.5 point Sabon by

Main Point Books, Edinburgh

Text © Alison Irvine 2025

For Eden, Isla and Sadie

Take your partners: the original Barrowland Ballroom

Barrowland Ballroom Archive

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Prelude: An Anything-is-Possible Moment

PART ONE: 2019

1 Like Floating

2 A Wee Night Out

3 At First I Was Afraid

4 Green Shoots

5 Ghosts of My Youth

6 Hold On

7 Are We Good For Doors?

8 The Whole Shooting Match

9 Before and After

10 Barrowland Legends

COVID

PART TWO: 2025

11 A Barrowland Renaissance

12 Who is in the Cloakroom Today?

13 Absolute Crazy and I’m Not Going Back

14 Horizon

15 Everybody’s Had a First Day

16 Always Grateful

17 Never-ending and Everlasting

Acknowledgements

Photo Credits

Foreword

WHEN ALISON IRVINE first published Barrowland Ballads in 2019, she gave voice to the soul of our venue. Not just the performers, but the bar staff, the cloakroom attendants, the security staff, the punters, and the dreamers. She captured the pulse of Glasgow through the lens of a venue that has seen it all. Now, six years on, I’m truly very pleased that she’s returned to it. The fact that she feels the original book needs updating says everything about the enduring magic of the Barrowland and the people who keep it alive.

There’s a particular kind of warmth here which, as Alison has no doubt discovered, is difficult to put into words because it’s more a feeling; it’s steady, generous, keeps on giving and is deeply Glaswegian. It lives in the quiet custodians, legends behind the scenes: the ones who serve up the drinks, the ones who look after the safety of the customers and the ones who sweep up after the last song. These are the people people who’ve watched generations grow up under the glitterball, who remember the faces even when the names fade. Their stories are still unfolding, still waiting to be heard. This new volume, Barrowland: The Inside Story of Glasgow’s Beloved Ballroom, which contains the original Barrowland Ballads chapters plus a new 2025 section, is their stage. As someone who’s spent a lifetime admiring the Barrowland and what it means to Glaswegians, I couldn’t be more pleased to see this next chapter come to life. Alison has once again tuned her ear to the voices that matter, and what she’s found is something worth celebrating.

So, the doors are open, step inside. The lights are low, the crowd is gathering, the tension is mounting, and the stories are ready to sing – Here we! Here we! Here we…!

Tom Joyes, General Manager, Barrowland Ballroom

Sign of good times: Barrowland’s iconic neon sign

Chris Leslie

Mirror ball

Chris Leslie

What I always remember about the Barrowlands is you could be a teenager sitting in your room and feeling as if you were completely alone and you’ve different thoughts and feelings and music taste from everybody else and then when you’re in there it’s almost like a sense of community. It’s like you’re looking around and you’ve got a connection with everybody.

Pammy Given, gig-goer

For me personally, this is the best concert venue I have ever set foot in bar none. The best feeling is when you are in the moment. You can feel the floor vibrate through your feet and the atmosphere created because of this and how close you get to the stage cannot and will not be replicated anywhere else.

Adam Boyce, gig-goer

Raw power

Chris Leslie

Introduction

DO I START with the neon sign on the front of the building, a skeletal web of tubes and wire during the day but at night, when switched on, a beacon of passion and promise, lighting up the Gallowgate?

Do I start with the cloakroom with its red floor and red metal rails, which is where you might start if you were coming yourself? If that’s the case, I should start with the ticket checkers at the door and the security staff who search bags and bodies. No, I’d start before that with the queue that sometimes begins around lunchtime and grows through the late afternoon and early evening. I could start with the girl from Spain, for example, sitting on the pavement in a parka while her parents walk up and down the street outside, reluctant to leave her to her gig.

I could start with bar manager John who plays Hank Williams relentlessly, religiously, and keeps three cowboy hats on a hook behind one of the bars. Or I could start with general manager Tom who has looked after the Ballroom and the Barras market for over 40 years and says not a day goes by, even when he’s on holiday, when he doesn’t think about the place. Or with Linda who has worked at the Barrowland since 1970 and is a direct descendant of Maggie McIver. Do I start with Maggie McIver, the woman who founded the Barras market and had the Barrowland Ballroom built as a venue for her traders’ Christmas balls?

Do I start with the ballroom itself and its sprung floor, on which a hundred thousand feet have danced or jumped or stomped a hundred thousand times? The ballroom ceiling with the acoustic tiles and the stars – those stars, I should start with them! What about the stage or the bars or the back stairs up which the world-famous crew load in the bands’ equipment? Do I start with the light bulbs around the dressing room mirrors?

Do I start with us? The gig-goers, the dancers, the out-for-the-nighters? Do I start with the sweat-soaked musicians, exhausted, euphoric, their eyes seeking – seeing – the eyes of the crowd and connecting?

Or do I start with the end of the night when it’s all over? The cleaners whose brooms brush confetti into piles, who put plastic cups into bin bags, or the security staff who search toilets for left-behind gig-goers and encourage us down the stairs.

I will. I’ll come to all this and all these people, and our stories too, because that is what this book is about. It’s a look at what makes the Barrowland Ballroom the special place it is.

Barrowland: the original building, 1934

Barrowland Ballroom Archive

It’s not headlines or gig reviews or superstars; it’s the stories of those who believe the Barrowland Ballroom is the best venue in the world. It’s about the people who work at the Barrowland and bring the magic and, along with the artists, of course, help elevate our nights to legendary status.

Collecting material

Chris Leslie

Note, I’m saying the Barrowland Ballroom with no ‘s’ (look at the sign!). I’ll be using its official Sunday name in this book (primarily because it’s a bugbear of general manager Tom Joyes’s to see it written with an ‘s’ and he’s the one who has put me on numerous gig guest lists and let me in behind the scenes so I need to do right by him). But there will be no judgement from me if you want to call the venue the Barras or Barrowlands and you’ll notice I haven’t changed the spelling when using direct quotes.

I’ll start briefly with how this book came about. I regularly work with two artists, photographer and filmmaker, Chris Leslie, and illustrator, Mitch Miller. We’ve been documenting the changing city of Glasgow for many years, having met in 2008 while working at the Red Road Flats. We first looked at the Barrowland Ballroom as part of our Glasgow Life-funded legacy project on the Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games, Nothing is Lost. How would the Games change the East End of Glasgow? What impact would they have on the cultural institutions already there? We loved documenting the Barrowland Ballroom and the Barras market and realised that this iconic establishment on the Gallowgate deserved more than just one chapter in a book.

Several years later we were awarded Creative Scotland, Glasgow City Heritage Trust and Merchant City Festival funding to publish Barrowland Ballads, a limited-edition book of essays, photographs, illustrations and a map-style drawing, too large to reproduce here. The chapters from that original book are included in this one and many of Chris’s photographs are included too. It was one of the most funny, fascinating and happy jobs I’ve ever worked on. I was given the equivalent of an Access-All-Areas pass to document the day-to-day life of the Barrowland Ballroom. I interviewed musicians, gig-goers, promoters, stewards, maintenance men and other staff – anyone who would talk to me. I knew I wanted to write about the day of a gig, from the load-in at 8am to the clean-up overnight; who does what and when and where, and how do the hours pan out? I wanted to take you through the sound check and the ticket checks and the purchasing of drinks to that sweet collective inhalation when the ballroom lights flick to black and the band steps on to the stage. I wanted to write about the cloakroom staff handing back coats and bags at the end of the night and the stewards assisting the last of the punters out of the building before the cleaners begin their shift work, and when they’ve gone, how the Barrowland belongs to one man again, the nightwatchman, and sometimes his dog.

Recollective

Chris Leslie

That project finished in 2019 and you’ll know what happened in 2020. The Covid-19 pandemic hit the world and the Barrowland Ballroom closed its doors. There were no gigs for over 14 months. Staff at Margaret McIver Limited, the company which owns the Ballroom and the Barras market, were either furloughed or instructed to work from home.

I remember my first gig back at the Barrowland once restrictions were lifted and I’m sure you will too. For me there was a mix of excitement and anxiety as I stood watching Billy Bragg with my husband, sister and friend. By the end of the night, we were hot, sweaty and exhilarated and above all relieved to be back watching live music in the Barrowland.

Since reopening after Covid, much about the Barras and the Ballroom has changed. The market is thriving thanks to an increase in customers and energy, and a cleverly balanced mix of old and new traders. The Ballroom has new bars, new drinks for sale, new flooring in places, new wood panelling, new upholstery on the main band room sofas – all carefully and sensitively done so you might not even notice the tweaks and changes. But the essence is the same, and the essence is what I want to capture for you, here, in these pages.

The book is essentially in two halves. Pre-Covid in 2019 and post-Covid in 2025. You’ll notice that each half is written in the present tense and, if you know the Barrowland well, you’ll be aware that some of the people and places I’ve written about in 2019 are no longer here. The Barras and the Barrowland are ever evolving, despite being famous for never changing. For example, one of the traders I spent a comical hour with recently no longer has a stall at the Barras. I returned one weekend to tell him I’d written about him, but his friend and fellow stallholder told me he’d gone. Tam’s burger bar is also no more. Some staff members have moved on, changed jobs or retired, but many remain at Margaret McIver Limited and it has been a pleasure to see them again.

Now, some history. The Barrowland Ballroom and the Barras Market are situated in the Calton in the East End of Glasgow. The main entrance is on the Gallowgate, not far from Trongate, the Merchant City and Glasgow City Centre. Margaret McIver Limited is a family-owned business and has been since its inception in 1921. Its current Managing Director is Dugald McArthur whose great-grandmother was Maggie McIver, the ‘Barras Queen’, the woman who founded the Barras. The Barras market began as a space where traders (or hawkers as they were then called, and sometimes still are) could come and trade from their barrows. Maggie and her husband James hired out the barrows. Each year, Maggie McIver would host a Christmas Ball and, after failing to secure a venue one year, she decided to build one for herself. Hence, the Barrowland Ballroom came about. It opened on Christmas Eve in 1934 and was extended in 1938. The house band was Billy McGregor and the Gaybirds and the Barrowland Ballroom was a thriving dance hall for many years until a fire destroyed it in 1958.

Maggie McIver, the Barras Queen

Barrowland Ballroom Archive

Maggie McIver had died in June of the same year and after the fire, her son, Sam, vowed to rebuild the Ballroom in her memory. It reopened on Christmas Eve 1960. The only surviving fixture from the original building is the neon cartwheel that hangs above the stairs as you come in. The Barrowland Ballroom thrived again and is famous for being the place where many couples met and courted. Ask a Glaswegian where their grandparents met and the odds of them saying the Barrowland Ballroom are high. The Barras remained popular – the huge crowds at the weekend market were legendary. Customers came for the bargains but also for the social, enjoying listening to the traders’ famous patter. Stalls were passed from family member to family member. Christmas Eves at the market were legendary, with traders not shutting up shop until midnight.

Barrowland’s popularity decreased after the tragic murders of three women who had gone there to dance. While the market continued to thrive, the Ballroom closed its doors in the 1970s, opening again for a brief stint as a roller disco venue.

In November 1983 Simple Minds used the Ballroom to film their ‘Waterfront’ video in front of a live audience and on 21 December 1983 of that same year the band came back to play three nights. The Barrowland Ballroom’s new life as a live gig venue had begun.

Which brings me to the question I frequently ask: What’s it like to play on the Barrowland stage? On this occasion I’m talking to Donnie MacNeil from the Vatersay Boys. His band has just been inducted into the Barrowland Hall of Fame and when I poke my head around the band room door to introduce myself he pulls me in for a photograph with his award. Sitting with him in the wood-panelled dressing room, beautifully lit by the light bulbs around the mirrors, are his bandmates. There must be 16 people at least squeezed into this small and iconic room. The gig hasn’t even begun and it’s a party. I ask Donnie for a quick chat and he says, ‘Sure, what time is it?’ I tell him it’s nearly 7pm. He stands up and I follow him out of the main band room and along the Hall of Fame corridor, past the dark drapes and up the ramp to the stage. Donnie walks to his drum kit and sits down. I want to ask him why we’re doing the interview on the stage – there are real punters out there filling up the hall; there are gorgeous waves of talk and laughter coming up to meet us – but it all seems so normal to Donnie that I push on with my questions. I know it’s their 16th sell-out show in the same number of years. So, what’s it like to play the Barrowland Ballroom? ‘Oh it’s horrendous, you don’t want to do it,’ Donnie jokes. What can you see from here? I ask. ‘I can see everything. I’ve got vision like an eagle.’ His voice booms over the kindling crowd. ‘I’m still playing. Sixty-one and still doing it. I just got an award this week.’ I know! I posed for a picture with you in the heady dressing room. How do you feel about that, the Barrowland Hall of Fame? ‘I’m aghast, agog,’ Donnie says. And that’s it. The interview concludes. Donnie sits at his drum kit, he’s joined by two of his fellow musicians and before I’ve even left the stage they begin the first bars of a ceilidh tune and the punters have started to dance. Soon the dance floor is a whirl of twirling couples, and the bagpipes and piano accordion and fiddles that join the drums and guitars on stage fill the hall with a bright, riotous sound. Donnie, at the back of the stage at his drum kit with his eagle eyes, takes it all in.

Still spinning: cartwheel from the original building

Barrowland Ballroom Archive

That is one of my most bizarre interviews. I also interview Jacquie. She played the drums in the first-ever band to officially play the Barrowland Ballroom. Yes. She supported Simple Minds in 1983 with her band Sophisticated Boom Boom. She became a school teacher and union activist. We’re sitting on the seats in the main band room and Jacquie is holding imaginary drum sticks in her fists, tapping her feet in her glamorous shoes and telling me about the black gloves she wore because she got blisters, how she used to hit the snare drum flat on the rim so it made a cracking sound, how drumming was physical and demanding, how sometimes her shins bled when the foot pedal swung back because she’d pressed it so hard and how if she was to play anything on the drums now it would be heavy metal. That gig they played at the Barrowland Ballroom: ‘I remember it being really loud. For us it was a big gig. Powerful,’ she says. Mel Gaynor, Simple Minds’ drummer, let Jacquie use a couple of his cymbals and he gave her some drumming tips too. Jim Kerr watched from the wings. ‘A wee bit of encouragement,’ Jacquie says. She was nervous and excited. The gig was a sell-out. ‘There were hunners and hunners of faces in the audience,’ and the crowd was nice to them. ‘We were a jingly jangly girl band and they were there to see Simple Minds. But we felt a bit of love for us.’ A wee ‘gothy punk girl from Castlemilk’ who formed a band out of a bit of fun one night in the Hellfire Recording studios, supported The Clash and did a John Peel Session, and she and her bandmates started off the gigs in the Barrowland Ballroom.

I was there in the audience for many Barrowland gigs, pressing punters for stories and memories. One such conversation involves an uncle and his nephew at a Gerry Cinnamon gig just before Christmas. Chris and Corey. They’ve taken the train from Port Glasgow and Chris has told Corey: ‘It’s Gerry Cinnamon, it’s the Barras, that’s a combination that’s going to be seismic.’ Corey seems awfully young but his back is straight and his feet are planted and he looks up for it. Around him there are groups of young men in trainers and skinny jeans, and young women with shiny hair and immaculate make-up. There are people passing by with pints in plastic glasses, couples standing arm-in-arm, a pensive, angular indie kid holding the hand of a porcelain-faced girl. We’ve just had the support – Rianne Downey playing a slowed-down version of ‘Country Roads’ and Dylan John Thomas with his zip-up top and confidence – and now the sing-along songs are on the PA before Gerry Cinnamon plays.

What’s your uncle told you about this place? I ask Corey. ‘Carnage,’ Corey says. Is it how you expected it? ‘No.’ What did you expect? ‘I thought it would be a bit more modern.’ That reminds me of a young woman I spoke to, also at the Barrowland for the first time, who said it reminded her of her school’s assembly hall. There is nothing modern about the Barrowland other than this young crowd. They’re keeping up the tradition of a Barrowland crowd being the best crowd, singing their parents’ or grandparents’ songs – Oasis, Beck, Bob Marley, Johnny Cash – without inhibition, claiming the songs for themselves. I wouldn’t be surprised if they burst into ‘Blanket on the Ground’. The hall is hot and buzzing. Then the lights go out to cheers and whistles and Gerry Cinnamon is lit up on stage, joy on his face, giving it his all and the crowd is taking it all and sending it back with love.

With the help of Barrowland’s House Photographer, Gareth Fraser, who is also one of Barrowland’s tour guides on Doors Open Days, I met devoted fans and collected their stories at Recollective’s story-gathering exhibitions in the Ballroom. I asked questions of fans on the Barrowland’s very active Facebook pages too. You’ll see I’ve included verbatim quotes at the beginning of each chapter. Sometimes the original words are the best words to use.

I interviewed the staff and asked them about the minutiae of their daily working lives. It was a pleasure to meet this hard-working, funny, kind-hearted bunch and I am extremely grateful for their enthusiasm and patience. I shadowed security stewards, chatted to first-aiders and spent time on the accessibility platform. I even worked shifts in the cloakroom and behind the bar. Hats off to the cleaning staff. I stayed with them till after midnight but didn’t manage a whole night shift. And after hearing some eerie stories about the Barrowland Ballroom in the middle of the night I avoided a shift with the nightwatchman, too. Some things are best left to the imagination.

You’ll know by now that this book is not a catalogue of bands and artists who’ve played the Barrowland; I may not even mention your highlights or standout concerts. It’s about what it’s like to play at the Barrowland, yes, and what it’s like to go there to see a gig, but above all it’s about the staff who work in the Barrowland and know it far better than we do. They’re the people who come to work on busy days and quiet days and who create for us on gig nights that special warmth and down-to-earth atmosphere for which the Barrowland is famous. Hopefully, you’ll recognise yourself in some of the memories. Going to the Barrowland is a shared experience, after all.

The Barrowland Ballroom is a phenomenally special place. Managing Director Dugald McArthur described being in the ballroom as like being inside a guitar: wood below and wood above you. The sound hums magnificently. And that’s what I would like to present to you here, in this book. I’d like you to step inside the Barrowland Ballroom, get right inside it and discover how this beloved instrument plays.

PRELUDE

An Anything-is-Possible Moment

That Simple Minds day really was a standout day in my life. You went home, your mum was like ‘How was your day?’ and you were like ‘That was life changing.’

Lesley Jones, journalist

IN THE OPENING frames of Simple Minds’ ‘Waterfront’ video, shot at the Barrowland Ballroom on 20 November 1983, a man walks slowly across the Barrowland dance floor to the sound of insistent, rhythmic clapping. He kicks an empty cup, one of many that are scattered on the floor. The clapping quickens to enthusiastic applause and the video cuts to the smiling faces, outstretched arms and waving hands of a crowd of young people. A second later, explosive drums and guitar kick in and then the video alternates between the lone figure on the dance floor and the wild, kinetic crowd at the gig. After a few more seconds there is a wide-angled shot of the Barrowland stage. Crossing white spotlights frame drum kit, keyboards, microphones, guitars. Billy McGregor’s acoustic ceiling tiles are lit up and three mirror balls sparkle in the light. On the dance floor, a thousand bodies are turned towards the stage where the Simple Minds musicians play.

Undoubtedly the star of this video is the crowd and the way the young people reach towards the camera, clamouring to be filmed, or lean onto the stage to touch singer Jim Kerr. Such manic, contagious energy. Even through the grainy video uploaded to YouTube you can get a sense of the excitement. You want to be there, to be part of that crowd.

Lesley aged 14 and Howard aged 22 are in that crowd. Lesley is squashed at the front next to the runway stage on the side of Mel Gaynor’s drum kit, because she loves his drumming. And Howard? He is towards the back somewhere, but he couldn’t tell you exactly where he is because it was over 40 years ago. He still has his ticket, though.

The Golden Ticket

Howard Young

The tickets are an important part of this Barrowland story because they were given away for free by music journalist Billy Sloan on his late-night Thursday show on Radio Clyde, and Lesley and Howard were lucky enough to win one.

I speak with Lesley, Howard and Billy about this auspicious day at the Ballroom. What strikes me as much as the facts – Jim Kerr’s suit was blue, the Minds played a live set as well as recording video footage for their single, the event kickstarted a run of gigs at the Barrowland that has yet to stop – is the variations in recollection that the three of them have; what they remember and what they don’t. I’m also interested in how, in small and momentous ways, being present at the filming that day has affected their lives.

I talk with Howard in a cafe in the Barras, with every table around us full with lunchtime diners and a queue of people waiting at the counter for takeaways. In 1983 he was 22 and the first person from his family who had been to university. He was unemployed and battered by job rejections. Between then and now he has circled the globe in pursuit of gigs and finely crafted beer.

I interview Lesley over Zoom. She has retained a bemused fondness for the seasoned gig-goer she was at 14, mad about music, clothes and hair gel. She’d already been to many gigs at the Apollo with her mum who was a social work assistant and was often given free tickets for the young people she worked with.

Billy worked in a shoe stall in the Barras when he was a teenager and started out as a journalist on the Springburn and Bishopbriggs Gazette. We’re in his Glasgow flat and he’s looking after his neighbour’s poorly dog who sits next to him on the settee and barks meekly from time to time.

So, the tickets.

Billy Sloan’s show ran from midnight to two. ‘I used to sit with a bunch of my favourite records and play them,’ he tells me. ‘I naively took the point of view that I think these are great records; maybe somebody else will think they’re great records too.’ He’s on the money there; Howard and Lesley were fans of his show.

As he regularly played Simple Minds records and the band had guested on his programme, he tells me the manager of Simple Minds, Bruce Findlay, said to him, ‘We need an audience. How do you fancy giving the tickets away?’ The dog barks. ‘What is it, sweetheart?’ Billy says to the elderly dog.

Howard had been unemployed for 18 months. Dozens of job applications and no offers. Not a sniff. He’d lost weight. ‘I was going downhill a bit,’ he tells me. ‘I’d done an MSc in Tourism and an MSc in Urban Planning. I’m from a working-class family. I’m of that generation where we were encouraged by our parents to go to university. So I’d studied hard, applied for everything and got nowhere.’ But music was a distraction. Billy Sloan’s late-night show, in particular. ‘Billy always used to play an interesting range of music,’ Howard says. He heard Billy’s call-out for audience members one Thursday evening.

‘Was it 1983?’ Lesley says as we talk over Zoom. She moved from her home in Glasgow to London several decades ago. I see her trying hard to remember the details and she seems as enthusiastic and overcome by the whole thing as I imagine she was as a teenager. ‘It would have been a show like Billy Sloan,’ she says. ‘Something alternative. But when I think about it, it may have been a more mainstream show on in the day.’

She was right first time.

Howard confirms. ‘Billy said that Simple Minds want to record live concert footage for a video they’re doing. And he said they’re looking for an audience. We’re giving away free tickets and if you get a ticket come along and be part of the audience for the recording.’

Billy asked listeners to send in a stamped addressed envelope to be one of 500 (‘Or was it 750?’ he asks) to receive a pair of tickets to the filming on 20 November 1983 at an unknown location. That location was the Barrowland Ballroom.

Howard and I are drinking coffees and eating filled rolls. I’m firing questions at him and he’s talking more than he’s eating but he does show me photographs of Nanci Griffith and Emmy Lou Harris from the times he’s met them before or after their gigs.

Until that point, the Barrowland Ballroom was empty. Occasional roller discos had taken place, including one in which a 12-year-old girl, Maria, had her birthday party (they used to get changed in what is now the main band dressing room) and before that there was the disco dancing in the 1970s, but there was none of the regular music and dancing that used to take place on weeknights and weekends. No live music. The Ballroom was a working venue, but dormant and dark.

I speak with Dugald McArthur, whose great-grandmother was Maggie McIver (his mother was the daughter of Margaret McIver’s daughter, Kitty Cairns). When he was a boy his family emigrated to Canada and, as a way of pacifying his bereft Glasgow family, his mother brought him back to Glasgow every summer and he spent his weekends helping his uncle Victor in the Barras and his weekdays helping his grandmother in the Ballroom.

‘What if the “Waterfront” video had not been done?’ he asks me. ‘Would this ever have happened?’ It’s quite the question.

Dugald remembers a directors’ meeting to discuss the proposal to record the video. His grandmother’s office was upstairs on the same level as the dance floor. He would sit with her on quiet days but he wasn’t allowed upstairs while that particular meeting took place.

Speaking to me as the firm’s managing director and not the boy barred from the Ballroom, he understands the considerations his predecessors would have given the proposal from Simple Minds’ team. ‘For us at the time it was rental income,’ he tells me. ‘I never heard anyone say definitively that that was part of a plan. I think what it became was an opportunity – and that’s what the business has done for years is seized an opportunity.’

So, ‘the comets crossed, the planets aligned,’ Dugald says. Kitty and the directors said yes to the filming of the video. ‘And then it became history.’

In 1983 Billy Sloan finished his evening show and took bin bags of stamped addressed envelopes to the Radio Clyde canteen. ‘We got thousands of people,’ he tells me of the number of applicants. ‘It was like the Blue Peter appeal. Maybe five, six or seven of these bin-liners filled to the brim. I thought, Christ, how are we going to do this?’

One at a time. He picked them out with his colleague, Ross King. They sat in the canteen from 2am when his show finished until sunrise, picking out envelopes, opening each one up, taking out the stamped addressed envelope and putting two tickets inside. Despite having had no sleep, Billy and Ross were savvy. They watched out for multiple names at the one address. Bob Burns, Billy Burns, Brendan Burns, Brenda Burns. They didn’t want to give extra tickets to someone when hundreds – thousands – of people would miss out. In amongst those envelopes were tickets for Howard and Lesley. Then, he says, ‘I walked along to George Square where the big main post office was and I stood at 6am when folk were going to their work and I physically posted them through the letter box.’ One by one. Off they went to their recipients.

Lesley displayed her ticket on her bedroom wall for years. She’s lost it now. Howard knows he still has his but he’s put it somewhere safe and can’t remember where. He posted an old photo of it on Facebook recently and caused a stir from hundreds of fans and ‘a Proustian rush’ for Lesley when she saw it after all those decades.

‘It was like Willy Wonka,’ Howard says. ‘Not a golden ticket but a silver ticket. “Turn up at the Barrowland, Sunday afternoon, for the filming of ‘Waterfront’.”’ He corrects himself. ‘The filming of a video. It didn’t say Waterfront.’ Until then, few people had heard the song: not Howard, not Lesley, not even Billy.

Lesley tries to remember what she wore. ‘I think I had jeans on and my favourite blue mohair jumper. And my hair as crazy as I could get it.’ She’d shaped it into spikes with her Country Born hair gel. Howard? Who knows what Howard wore, he can’t remember. ‘Probably a T-shirt. But maybe something fairly warm because it was November.’

It was November, yet Lesley remembers the sky being a brilliant blue while she waited in the queue outside. She had never been in the Barrowland Ballroom before but she’d heard of it. Lesley had been friends with twin girls whose grandpa was Billy McGregor who sang with his band, the Gaybirds, in the Barrowland back in the day. (Remember the ceiling tiles that stand out so clearly on the video? It was Billy McGregor who’d asked for them to be installed to enhance the acoustics.) She’d got on well with the girls’ mum, Ray, who used to tell them stories about her daddy and the band and the Barrowland. Lesley’s dad knew of the Barrowland, too, being a policeman. But apart from this, there was no significance to standing outside the Barrowland Ballroom on a sunny winter’s day, about to go in. ‘I don’t remember feeling excited that I was going to get inside Barrowlands for the day,’ she says. ‘I was excited about possibly being on the telly and seeing Simple Minds.’ So she waited in the queue with her pal on this blue day. It was one of her first gigs without her mum.

And Howard waited, too. He went on his own, less bothered about getting on the telly, and more bothered about seeing Simple Minds. ‘Oh, I was a fan!’ he says. ‘I absolutely loved them and I thought they were brilliant. I first saw them when they were Johnny and the Self Abusers.’ He, too, knew of the Barrowland Ballroom. He knew of its past and he was a fan of the Barras market. He tells me he used to come for a look around. ‘Pick up a bootleg. Go to the cafe. You never know what you’d find. It was such a great place.’

Waiting in the queue outside the Ballroom, he spoke with the people next to him. ‘We all considered ourselves quite lucky we’d got a ticket.’

Billy, meanwhile, was in the dressing room with Simple Minds. He’d spent the previous day, a Saturday, filming on the Renfrew Ferry with the band. (If you watch the video you’ll see that the Barrowland footage is interspersed with shots of the River Clyde and the band on the ferry.) He’d never been to a video shoot before the ‘Waterfront’ shoot and he’d never witnessed a recording with a live audience. I ask him if he spoke to the crowd in between takes, to keep them entertained during the breaks in filming. ‘Perhaps,’ he says.

Lesley tells me she liked Simple Minds’ music. She was of the same tribe as other music fans in Glasgow, those of the black-walled bedrooms, the ripped-up jeans, the painted T-shirts, the spiked hair. Simple Minds’ music belonged to that tribe. She and Jim Kerr went to neighbouring schools – hers King’s Park and his Holyrood (although he was nine years older than her) – and there was something exciting about living near him, about being from the same part of the city as him. Close enough to pass on the street if the comets and the planets aligned.

When the Simple Minds video crew was ready, Lesley and Howard were let into the Barrowland. They climbed the first set of stairs with doors leading to the area we call the Crush with the merch stand and toilets and Revue Bar off it, and then up the stairs to the ballroom. Which set of swinging double doors they went through we don’t know, but they’ll have walked into the ballroom with the other people and stepped onto the Maplewood floor with its stage prepped and ready for a gig, albeit a manufactured one.

Look up!

Chris Leslie

‘The mirror ball is what I remember,’ says Howard. ‘I just have a general picture of this big open venue, the slightly higher stage, Simple Minds all set up.’

‘I remember sprinting to the front, getting squashed against the stage and hardly being able to turn round to get a good look at the place,’ Lesley says. ‘It certainly wasn’t very razzamatazzy from what I could see. It seemed to me very dull and black. And the catwalk thing we were squashed up against was just kind of black painted plywood. Nothing fancy.’

‘Wow. This is amazing,’ Howard thought when he walked into the ballroom. ‘The equipment was set up on the stage and they had a thing down the centre with the audience each side.’ Immediately, he saw the Ballroom’s potential as a gig venue. ‘Why do we not know about this place? This is a great venue,’ he remembers people saying to each other.

Lesley and her friend Lauren picked a spot at the front. ‘It was set out with a stage and the drums were off to one side. The side I was on, I could get quite a good look at Mel playing drums. He was my focus because I always thought he was an absolutely brilliant drummer. I still do.’ Howard chose a spot further back where it was less crushed and he felt, at last, at home. ‘Like-minded souls’ is how he describes his fellow audience members. Job applications, unemployment, mental fatigue – they could all disappear for a few hours while the band played.

Lesley says, ‘There was good humour between everybody. It was just chaos. Fan adoration. There wasn’t like all the cool kids standing about going “Oh right, are we going again?” It was like “Raaaaahhh!” It was a rammy.’ We talk about the video and she says, ‘You can see how squashed everyone was. I mean the health and safety nowadays would have gone crazy. We must have been in there for hours. I’m five foot ten. My pal Lauren who was with me was up to my shoulder. I’m surprised she didn’t faint. I do remember thinking Oh it’s been about four hours now since I had a wee. But I’m not going anywhere!’

Here is where facts and memories converge and diverge and overlap and contradict, and the beauty of this story is that it doesn’t really matter. The facts are that Simple Minds recorded the video for their ‘Waterfront’ single in the Barrowland Ballroom on 20 November 1983, Billy and Lesley and Howard were there, and after that the Ballroom went on to host gig after gig after gig. The rest, I guess, is legend.

Howard’s version: ‘Simple Minds came on and said we’re going to do scenes from the video but as a thank you, we’re going to play live for about an hour, an hour and 15. And they did. They played live.’

Lesley’s version: ‘I think they ran through it at least three times. We must have heard it three or four times, one after the other. They were filming it from different angles.’

Billy’s version: ‘Now the nature of video shoots is that you get herded about like cattle because they’re re-setting the lights and the camera angles. And even though the fans were diehard fans, after about eight times of hearing Simple Minds mime to “Waterfront” they were a bit fatigued. So, to offset that, Simple Minds said we’ll play a gig.’

Yes, but what came first? I ask Howard and Lesley and Billy, the live set or the video recording?

‘I wish I could remember, but it’s 42 years ago,’ says Howard, but then he says confidently, ‘The live set. Then there was a break and there was all the set-up for the cameras and stuff. If it hadn’t been for the live set at the beginning I’d have gone “Oh, bloody hell, this is a pain.”’

‘They did play a few songs afterwards,’ Lesley says. ‘It’s a sprung floor, isn’t it? The place absolutely jumped.’

So, the live set came after?

‘Yes,’ says Billy. The filming came first, the however-many run-throughs of the song from start to finish came first and then, he says, ‘They played a gig for an hour. They actually played live for an hour.’

And were they playing live for the video recording? ‘This is what I’m trying to remember,’ says Lesley. ‘The playback was really loud and the sound was immense. I remember feeling the drums go through my ribs. I was about three or four steps away from that drum kit. Was Jim Kerr miming? I don’t feel like he was. But he was obviously lip-syncing and with maybe a live overtrack. I don’t remember watching him and thinking Oh, this is like you doing a pantomime of a pop single. It felt live and direct.’

Howard? ‘They weren’t playing their instruments. Jim Kerr might have been singing but I’m not sure. I can’t confirm one way or the other.’

Billy? ‘From memory, it was a lip-sync, they were miming it,’ he says. After the filming of the video, he says, ‘I came onstage. I said, “Look, I’ve got a band in the back. They’ve never played the Barrowland before,” because nobody had at that time. And I said, “They’re a wee bit nervous. They want to play the Barrowland. So will you please welcome Mel Gaynor and the Self Abusers.”’ And, being the crowd they were, knowing their music, they would have known that Simple Minds had previously been called Johnny and the Self Abusers. ‘Of course, the cheer went up and on they came,’ he says.

And what was it like? What was it like to be in the crowd while the video was being filmed and during the live set, whichever came first?

‘The sound was amazing,’ says Howard.

‘The crowd played their part. They were kids, but they were diehards. And if you watch the video the crowd looks as if they’ve only done it once,’ says Billy.

‘The place went nuts,’ Lesley says. ‘Completely nuts.’ The floor bounced. Her ribs were squashed against the side of the stage. Her hair gel dripped down her back; her carefully tended spikes were flattened against her head. For hours, she stood there, screaming and reaching out to touch the band members, especially Jim, as he strutted past. Jim’s suit was blue. ‘It was his prancy kind of dancey stage. His tip-toey dancey stuff. He had weird white socks on and patent leather shoes. They looked like spats. He was like some hobgoblin.’ She says that everyone wanted to be on camera. ‘There might have been a guy with a camera going up and down, but it was on that ground level so he could get the faces. That’s why it was so crazy at the front.’ She remembers wondering if she would even like the band’s new song. ‘But you know, I did. I really did. Because it had that amazing beat that I’m always after.’

She says she looked around that day and saw people that looked just like her. ‘It was like going to church, in a way that I would understand, because I’m not religious. You felt at home and you had a sort of common something to worship, you know. And you felt the same things that those other people were feeling.’

So, just like Howard, she felt at home.

The band played it cool. They were at their work, after all. There was little chat between them and the fans in the audience. If there had been, Lesley imagines, there would have been a riot – all the kids in the crowd would have wanted to have been chatted to. So the musicians kept it cool and took it seriously and acted like rock stars.

And yet. Lesley felt a kinship between them and her, between band and audience. A fire was lit. ‘It did something to my brain that day,’ she tells me. It was something to do with everyone being from Glasgow. Something very democratic happened in the room. These young men on the stage – extraordinary rock stars – only a few years older than her but from a place and a background that was familiar to her and to many other people in the crowd.

‘Things are possible in Glasgow,’ she realised. If they could do it, so could she. ‘I remember thinking Oh, that’s what it’s all about. I’d always wanted to be a journalist and write about bands and I thought, Well, I could do that. He can be a popstar so I can be the person that writes about the popstars. It was an anything-is-possible moment.’

Empowering, I suggest, and she agrees. And not just because she saw people like her on the stage and in the crowd but also because of the manner in which she got her ticket. A free ticket in a free and fair ballot, picked out by the DJ himself, sent by post and landing on her doormat. No money exchanged. All for the price of two stamps and two envelopes. No waiting lists, no guest lists, no ‘Who’s got the richest mum and dad or who can click on the link first?’ she says. A room full of ‘working-class kids just like me everywhere I looked.’

She left the Barrowland Ballroom that day hot and sweaty, with her mohair jumper tied around her waist and her gel-soaked hair flat against her head, exhilarated, buzzing, steam coming off her as she walked out into the bright blue day. She questions the sunshine part of her memory. ‘Am I getting this right? Or was it such an amazing day that I’ve imagined it being fierce sunshine and freezing cold?’ Let’s let her have the stunning Glasgow weather, shall we?

‘That was a real seminal time for me,’ she says. She got her first boyfriend a week later. She went to dozens of gigs at the Barrowland after that. She didn’t study journalism, but she did eventually become a journalist. ‘My first big job was pop editor of Blue Jeans magazine.’ Her career took her to Mizz magazine and countless glossies and women’s weeklies and she has spent her life writing about music because on that day in November 1983 she believed that music journalism was a life she could have.

Howard continued to apply for jobs. ‘I tried everywhere. I got all these rejection letters and eventually they didn’t bother sending any because there were too many people applying.’ He got his first job soon after the ‘Waterfront’ video recording and was a town planner for 40 years, becoming branch secretary for Unison and the first elected convener of the RTPI (Royal Town Planning Institute) in Scotland. The pain and indignity of all those rejection letters he received when he was so young and so qualified but so unable to secure a job still affects him and he has always found solace in music. ‘I got lucky,’ he says. ‘I was of that generation. We got good music. We got an education. There’s a T-shirt: I may be old but I got to see all the good bands.’ His salary enabled him to travel the world to see bands and artists he adored – Nanci Griffith, King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard to name two – and to return, of course, to the Barrowland Ballroom time after time, choosing a spot for several years by the main bar, downstage right, and in later years finding a better spot downstage left. ‘I just come in the front bit. There’s wee bits of space. Even with a big crowd, you still get gaps, and you can go in and stand and get some good pictures.’

‘You can escape to a different world with music,’ he says.

After the ‘Waterfront’ video, promoters Regular Music began to use the Barrowland Ballroom as a gig venue for shows on any night of the week. Not just weekends but on weeknights too. ‘Regular Music did what it said on the tin,’ Billy says as we talk in his living room with the wee dog changing position from time to time on the couch or barking hoarsely for water before curling onto Billy’s lap. ‘Regular Music revolutionised how we went to see gigs in Scotland.’ Soon after the filming of ‘Waterfront’, Simple Minds were back to play three nights, then it was the turn of Big Country. In 1984 came The Clash, and Simple Minds again, Spear of Destiny, The Smiths, Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Cure, Aztec Camera, Depeche Mode, Echo and the Bunnymen, Grandmaster Melle Mel and the Furious Five, Level 42, Motorhead, UB40 and Marillion. Quite the year.

I like the idea of Billy Sloan, who now has a late-night Saturday slot on BBC