8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

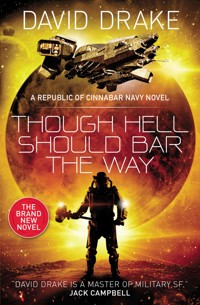

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: The Republic of Cinnabar Navy

- Sprache: Englisch

David Drake [is] the reason a lot of people got started reading military science fiction, because it's always a good idea to start with the best.--David WeberRoy Olfetrie dreamed of becoming an officer in the Republic of Cinnabar Navy until his father's secret criminal enterprise was discovered. Forced to drop out of the Academy, Roy has given up – until he meets Captain Daniel Leary.With Leary and Mundy at his side, Roy finally has a chance to redeem himself. Plunged back into the fray, Roy must contend with slave traders, pirates and assassination attempts, as well as his own father's toxic legacy. But an even greater danger is on the horizon, as war with the Alliance is brewing once again…

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 708

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by David Drake and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

ALSO BY DAVID DRAKE AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

THE REPUBLIC OF CINNABAR NAVY SERIES

With the Lightnings

Lt. Leary, Commanding

The Far Side of the Stars

The Way To Glory

Some Golden Harbor

When the Tide Rises

In the Stormy Red Sky

What Distant Deeps (July 2018)

The Road of Danger (October 2018)

The Sea Without a Shore (January 2019)

Death’s Bright Day

Though Hell Should Bar The Way

Redliners (April 2019)

THE REPUBLIC OF CINNABAR NAVY

DAVID DRAKE

TITAN BOOKS

Though Hell Should Bar the Way

Print edition ISBN: 9781785652318

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785652325

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First Titan edition: June 2018

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2018 by David Drake. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:

www.titanbooks.com

To Evan Ladouceur, who already has had not only repeated acknowledgments in this series, but also had a superannuated light cruiser named after him.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Classicists won’t be surprised to learn that the idea for this book sprang from the events leading to the outbreak of the Second Punic War. I probably have more classicists among my readers than most other writers, but even so I doubt they’re a majority.

Though that was the germ of the novel, the business of the book is more concerned with piracy. Pirates have become a big deal in recent years, but even when I was a kid there were plenty of child-accessible books about them. I particularly remember a big volume with what I now suspect were N. C. Wyeth plates. An image which is still vivid with me was of buccaneers in a small boat closing on the stern of a Spanish galleon.

As I got older, I read quite a lot more about pirates—but these were the pirates of the West Indies and the East Coast of North America. There were pirates other places too—Captain Kidd operated in the Indian Ocean—but they were pretty much the same: They captured ships and stole the cargo, behaving with greater or lesser brutality to the crews and passengers.

There were also the Barbary Pirates in the Mediterranean. I knew about them because one of the first steps the newly United States took on the international stage was to mount an expedition against them in 1801.

A catchphrase of the day was, “Millions for defense but not one cent for tribute!” Pirates from North African ports were capturing American ships and holding the crews for ransom unless the US paid tribute to Tripoli, Tunis, Algiers, and the Kingdom of Morocco, as most European nations did. Instead, the US sent a naval squadron.

Much like the 1968 Tet Offensive, the expedition had a considerable effect on public opinion back in the US, but considered simply as a military operation it was an expensive failure. There were quite a lot of heroic endeavors by American sailors—and I read about them with delight—but in fact the expedition’s major success was to burn one of its own ships in Tripoli harbor after the pirates had captured it. This was truly splendid exploit, but burning your own vessels isn’t a good way to force an enemy to change its ways.

The Barbary Pirates continued to operate until France conquered the region later in the nineteenth century, but that’s another matter. The crucial thing, which I didn’t realize until I visited Algiers in 1981, is that the Barbary Pirates weren’t in the business of looting ships: They were capturing slaves.

I’m not the only one who was ignorant on the subject. A few years ago I commented to an intelligent friend that the pirates captured European slaves in numbers comparable to the numbers of African slaves shipped to the Americas. (The real figure is more like a tenth, but this is still about a million European slaves.) He accused me of getting my facts from Fox News.

Well, no. I’d noticed the wonderful tile work in many of the older buildings in Algiers (and since many such buildings have been converted to public use or into foreign missions, this isn’t as hard as it may sound). When I asked about it, I learned that charitable organizations in European countries in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were set up to buy back enslaved sailors.

The Dutch, as one of the greatest trading nations of the period, provided a large number of both slaves and charities. Much of the ransoming was done with goods rather than gold, and the pirates turned out to be very fond of Delft tiles. The evidence is right there today for any visitor to see.

When we visited Iceland a few years later, I learned that Barbary Pirates had captured the city of Vestmannaeyjar and carried the profitable part of the population off as slaves. (Old people were burned alive in the church.) Piracy was definitely big business, in North Africa as surely as in the Antebellum South.

There’s quite a lot of information about the slave-based economies of the Barbary States. I prefer to get my history from primary sources—the history really isn’t as good, but it gives the reader a much better notion of how the culture felt, and that’s important from my standpoint. There are the accounts by ransomed slaves, by free Europeans working in the Barbary Kingdoms (generally in specialist trades like medicine or gunnery), and by European officials representing citizens of their nations in the kingdoms. I found a great deal of material.

It’s important to remember that slavery was a business. The pirate kingdoms weren’t civilized by modern standards (or even by those of the Antebellum South), but there were laws, and the trade in slaves was regulated by both law and custom.

My purpose, as always, is to tell a good story. I hope I’ve done so here. But readers who recall that the human interactions I describe are neither invented or pre-invented (which is how I tend to think of Fox News) may learn some things they didn’t previously know.

—Dave Drake

david-drake.com

…Then look for me by moonlight,Watch for me by moonlight,I’ll come to thee by moonlight,though hell should bar the way.

—Alfred Noyes

“The Highwayman”

Chapter One

“Now watch that you don’t take this corner too short again!” Cady snarled as we approached the entrance of Bergen and Associates. “If you knock the gate post down, the repairs come straight out of your pay!”

“Yes,” I said, not shouting, not mumbling, just speaking in an ordinary voice. If I didn’t say anything, he’d keep shouting at me, and I was already nervous about turning into the shipyard.

I had clipped the corner of the Petersburg warehouse yesterday, the first time I drove the chandlery flatbed. There was no real harm done: paint smeared on the side of the truck, and wood splinters bristling on the edge of the building.

I’d sanded the corner off and repainted it on my own time; not even Cady could claim that the battered old truck was damaged so that it mattered. You could’ve used it for a gunnery target and it wouldn’t look any worse than it did already.

Still, it saved Cady from finding something else to ride me about. Though he’d have managed regardless, of that I had no doubt. Cady didn’t have any real rank at the Petersburg Chandlery, but he’d married old Fritzi’s daughter. Any time Fritzi wasn’t watching, Cady acted like he was the boss.

I downshifted into the creeper gear and started hauling on the big horizontal steering wheel. I was trying to watch in both side mirrors while Cady kept yammering at me. I got the nose through and stuck my head out of the cab to shout at the watchman: “Petersburg to pick up three High Drives for reconditioning?”

The watchman was missing his left ear and the sleeve on that side was pinned up. He squinted at his display and called back, “That’s Bay One, to the left. Back right up to the dock. I’ll let ’em know you’re here.”

Bergen and Associates was big for a private yard. Three four- to six-thousand-ton freighters were being serviced now, and the docks could hold vessels much bigger than them. I was facing BAY 2 in big red letters across a trackway two hundred feet wide. I turned left, keeping close to the administrative buildings along the back fence, and pulled up when I thought I’d gone far enough.

“If you’ll get out and guide me,” I said to Cady, “I’ll back up to the loading dock.”

“Who do you figure you are to give me orders, Academy boy?” Cady said, leaning against the cab door to face me. He was a big fellow and not as fat as he was going to be in a few more years of beer and fried food.

“I’m not ordering you, Cady,” I said. I wished I’d come alone, but this really was a two-man job. I unlatched my door. “Look, you back her up and I’ll guide you, I don’t care.”

“Well, I bloody care!” Cady said. “You don’t need a guide. Just do your bloody job!”

I hopped out of the cab and walked toward the admin building. An old spacer came out the door, calling something behind him. “Hey, buddy?” I said. “I need a ground guide over to Bay One. You got a minute?”

I wasn’t going to back through the shipyard without a guide. There wasn’t a lot of traffic, but a lowboy was trundling past behind a tractor right now.

Besides, it’d just be stupid. I couldn’t help that Cady was being a jerk, but he wasn’t going to make me stupid.

“Yeah, sure,” the spacer said. “You’re here for those High Drives I want rebuilt?”

I opened my mouth to agree when the door opened again, and I recognized the girl who’d come out behind him.

“Roy!” she said. “Roy Olfetrie! It is you, isn’t it?”

“Hi, Miranda,” I said. “Gosh, I hadn’t thought to run into you. What’re you doing at Bergen’s? Working in the office?”

Miranda was dressed pretty well for a clerk, but she and her mother could sew like nobody’s business. She’d never looked out of place when our families got together after her father died as an RCN captain, leaving his widow and two children on a survivors’ pension.

The woman in RCN utilities who followed Miranda out of the office was six and a half feet tall. Her open left palm looked like she could drive spikes with it, and the expression she gave me made me think that I’d do for a spike if I got out of line.

“Not exactly,” Miranda said with the laugh I remembered from the old days. “My husband owns the yard. I’ve come up in the world, Roy.”

I smiled, but I guess there was something in my face because Miranda suddenly looked like I’d started sobbing. Which I hadn’t done, even when it first happened.

“Ma’am?” the spacer I’d first spoken to said to Miranda. “I need to get back to the Pocahontas. And kid?” This to me. “I figure Chief Woetjans can guide you as well as I could.”

“Look, kid!” Cady shouted from the truck. “We got work to do. Get your ass back in here!”

“In a bit!” I called over my shoulder. I felt hot because of what I’d done to Miranda, or anyway how I’d made her feel even though I hadn’t meant to. “Look, Miranda, the problem was nothing to do with anybody but Dad himself. I couldn’t be happier that you’ve been doing well. I don’t know anybody who deserves it more.”

“I heard about the trouble,” she said, turning her eyes a little away. “I was very sorry.”

Everybody on Cinnabar had heard about “the trouble,” I guess, at least if they paid any attention to the news. That was just the way it was, same as if I’d been caught in the rain. Only a lot worse.

“Well, it’s not so bad,” I lied. “I dropped out of the Academy and got a job with a ship chandler for now. After things settle down I’ll look for something—”

“Watch out!” Miranda shouted, looking past me.

I hunched over. Cady’s big fist grazed my scalp, but he didn’t catch me square in the temple like he’d planned to do.

I punched him twice in the gut, left and right. I’d boxed at the Academy. I didn’t have the footwork to be welterweight champion, but the instructors said I had a good punch. A bloody good punch, and I was mad enough to give Cady all I had.

I stepped back as Cady dived forward on his nose. He’d been trying to grab me with his left hand and just overbalanced when I doubled him up. He wasn’t hurt bad, but he’d remember me every time he sat up for the next few days.

Cady got his feet under him but didn’t stand. “Cady!” I said. “Let’s quit now and it won’t go any further!”

I wasn’t sure what to do next. Hitting Cady on the head wasn’t going to do anything but break my knuckles, and there was no way I could keep punching him in the gut without him getting a hand on me. Then it’d be all she wrote: It’s not like there was a referee to call him for fouling me, after all.

Somebody’d been opening crates at the edge of the loading dock. When Cady finally stood up, he had a crowbar in his right fist.

“Hey, kid!” called the big woman with Miranda. I let my eyes flick toward her. She tossed me the length of high-pressure tubing that she must’ve been holding along her right leg. I hadn’t seen it behind Miranda.

“Hey!” said Cady as I caught it. I cut at his head. He got his left arm up in time to block me, but I heard a bone break when I caught him just above the wrist.

Cady swung the crowbar in a broad haymaker that would’ve cut me in half if it’d landed, blunt as the bar was. I stepped back and smashed his right elbow so his weapon went sailing into the trackway, sparking and bouncing on the packed gravel.

I guess I could’ve stopped then—yard personnel were swarming around, most of them carrying a tool or a length of pipe. I had my blood up, though. Cady’d given me a chance to get back not just at him but at the way the world had gone in the past three months.

I cracked him on the forehead with all the strength of my arm. He went down on his face, bleeding badly from the pressure cut.

I moved back and hunched to suck in all the air I could through my mouth. People were talking—shouting, some of them. I could hear them, right enough, but it was like hearing the surf: There was a lot of noise, but my brain wasn’t up to making sense of it. I started to wonder if Cady had connected better with my head than I’d thought he had.

The big woman walked up beside me and shouted, “All right, spacers! Two of you get this garbage out the gate and into the gutter, all right?”

I straightened; I was all right now. “Wait!” I said. “He’s been injured.”

“You got that right,” chuckled a man holding a ten-pound hammer. “Nice job, kid.”

“Look,” I said, not sure how to say what I meant. For that matter, my brain wasn’t as clear as I’d like it to be. “He needs medical attention. This yard’s got a medicomp, doesn’t it?”

It must. Bergen and Associates were too big and successful not to.

“Yes, bring him in,” Miranda said. “That’s all right, isn’t it, Master Mon?”

“If you say so, Mistress,” said the man in a suit who’d come out after the fight started. “Tapley and Gerstall, get him into the unit.”

He looked at me, friendly enough but sizing me up just the same. He added, “It looked to me like he was getting about what he deserved, though.”

“Yeah,” I said, “but I don’t want to kill him. I didn’t even want to fight him.”

I’m out of a job. The sudden realization almost made me vomit. Knocking Cady out wouldn’t hurt me for getting another job particularly, but I’d had trouble enough getting in with Petersburg. Maybe being out of the news for three more months would help this time.

Men were hauling Cady inside to where the medicomp was. I started to give the length of tubing back to the woman who’d loaned it to me, then realized the tip was bloody. I wiped it on the leg of my trousers—I’d have used Cady’s shirt if I’d thought about it soon enough—and handed it to her. “Thank you, ma’am,” I said.

She chuckled. “I guess I’d have done more if it seemed like I needed to,” she said. “Which I sure didn’t.”

“What’s all this about?” said the fellow Miranda had called Mon. He must be the boss, because most of the folks who’d come over to watch were going back to their work.

“Sir, nothing, really,” I said. “We’re just here to pick up three High Drives for Petersburg Chandlery and, well, Cady took a swing at me because I was chatting with Mistress Dorst.” Which she wasn’t, but it was too late to change even if I’d known Miranda’s married name.

“That’s right, Mon,” Miranda said. “Roy and I are old friends. Our mothers are cousins, you see.”

Mon shrugged. “No business of mine, then.” He looked at the workmen still present and added, “Raskin, get this truck to Bay One and load it up. Weiler, Jackson, you give him a hand.”

Then to me again, “You just sit for a bit, Master. Come into the office and we’ll find you some cacao—or a shot of something if you’d rather. I don’t want you driving until you’re doing better than you are right now.”

“Thank you, sir,” I said. “I’ll be all right by the time they’ve got the truck loaded, but my throat’s dry, that’s a fact.”

“Roy, I’ve got to run now,” Miranda said, “but drop in and see me some time soon, please. Miranda Leary at Chatsworth Minor in the Pentacrest District.”

She waved and went off with the big woman—Miranda’s bodyguard, obviously. She looked able to do that job, no question.

I followed Mon inside and down a short hallway to his office in back. There wasn’t a clerk or receptionist. “So … ?” he said, pouring cacao for both of us. “You know Mistress Leary pretty well?”

It was obvious that there was a right answer and a wrong one to that question, at least in Mon’s mind. I took the mug and said, “Her twin and my older brother Dean Junior were best friends right up and through the RCN Academy. They were both killed in action. I don’t think I’ve seen Miranda in two years.”

That was the truth. What I say is generally the truth. When I was a kid I learned that I’m not a good liar, and I’ve never tried to get better at it.

Mon gestured me to a couch and sat behind the desk. I drank. I figured I’d finish the cacao and go out to the truck. They’d probably be finished loading it by then, and if not, it’d still give me a chance to work off some of the tremors.

“Six always had an eye for the ladies,” Mon said with a nostalgic smile. “He sure picked a different one to marry, though. Mistress Leary is sharp as sharp. Not that she’s not pretty too, I mean.”

“I’ve always thought that about Miranda,” I said. “At any rate …”

I look a long swallow; the cacao had been sitting awhile and wasn’t over warm.

I stood and set the empty mug by the pot. “At any rate, she was too smart to let my brother get any further than good friends. A lot of girls weren’t. Junior was a fine man and a fine RCN officer, but he wasn’t the marrying kind.”

Mon chuckled as he walked me out of the office. “To tell the truth,” he said, “I’d have said the same thing about Six. But he found a good one when he changed his mind.”

As I crossed the trackway, I noticed that the Bergen yard seemed a happy place as well as a busy one. I was pretty sure that if I asked Miranda to have me put on here, she’d make it happen.

I’d rather swab latrines than do that. I hadn’t tried in two years to see her. I wasn’t going to show up as a beggar now.

But the rent was due at the end of the week, and I wouldn’t bet Fritzi was even going to pay me for time worked. He didn’t treat Cady like much, but Cady was still family.

Oh, well. One thing at a time.

Chapter Two

I looked out the window of my room, holding aside the towel I’d nailed up to cover the casement. Not that anybody across the broad arterial was likely to be looking into my fourth-floor room—or that it would matter if they did.

At least I could pay for the room tomorrow. I’d told the disbursing clerk to give me my time, so I had three days wages in my pocket. Plus the florin and thirty-five pence I’d had left from last week’s pay.

Pascoe, the clerk, had heard Fritzi bellowing. I’d closed the office door when I went in to explain, but that didn’t help much. Pascoe hadn’t asked Fritzi whether “Get out!” meant with my pay, and he’d even given me the hour I was still short of quitting time for the day. I hoped he wouldn’t get in trouble for it.

I could generally pick up casual labor on the docks, though it wasn’t steady enough to afford the room. I really didn’t want to move into a flophouse, but I guessed it was going to come to that.

Tomorrow I could start walking the chandleries again. Or I could go to the shape-up at the docks and then look for something better in the afternoon if I wasn’t picked. I’d sleep on it.

Somebody knocked hard on my door—on the doorframe, not the panel. I wasn’t sure the panel would have taken that kind of use.

“Come in!” I said. If it was Mistress Causey, coming for her rent early because she’d heard about my job, then I wasn’t going to be polite.

The door opened. In the hall were a fellow of maybe thirty in a business suit, and an older man who looked like he ought to be leaning against a barn chewing a straw.

“You’re Roy Olfetrie?” the younger man said.

I swallowed. “Yes, I am,” I said. “And I’ve seen your picture. You’re Captain Daniel Leary.”

God and the saints: Miranda was married to that Leary. The war hero.

“I know that,” said Captain Leary with a friendly smile. “Now, come down to the bar and let me buy you a drink while you tell me about things I don’t know. About yourself.”

“I’d be honored to drink with you, sir,” I said, stepping out into the hall with him. I wasn’t much of a drinker, but I’d sure thought of tying one on this afternoon when I left the chandlery. “Ah, the bar on the ground floor here isn’t a great place, though.”

“I’ve drunk in worse,” said Leary.

The rustic got to the stairs ahead of him but called back over his shoulder, “I’ve carried him out of worse, legless and singing ‘I don’t want to join the Army.’”

Nobody tried to come up while we were going down, but a man was sprawled in the corner of the second-floor landing. He’d been there when I came home, too. He might as easily as not be dead, but there was nothing I could do for him.

Leary and his companion stepped over the fellow’s legs just as I had, so I supposed they really did know about buildings like this one. It had been new to me when I moved in, but I’d learned fast.

The bar was pretty busy for midweek. There was a piccolo in the corner wailing that it wished Mama didn’t flash her tits. There was an empty booth in back.

“What’ll you have, Olfetrie?” Leary asked.

“Beer, I suppose,” I said. It was less likely to poison me than spirits in a place like this, and I wanted to be awake early to make the shape-up.

“Hogg, get us a pitcher of what they have on draft,” Leary said. “Bring it over to the booth.”

We went to opposite sides. As I started to slide in, the bartender called, “Hey! That booth’s Cabrillo’s office when he comes in!”

I got out again. The rustic, Hogg, said, “Well then, we’ll discuss that with Master Cabrillo if he comes in, won’t we?”

He reached into a pocket of his shapeless tunic and came out with a knuckleduster. I guess he touched something because a blade shot out of the top end.

“Till then …” he said. “A pitcher and three glasses. Clean ones if you’ve got anything clean in here.”

“Sit down, Olfetrie,” Leary said. “I don’t expect we’ll be long enough for there to be a problem. If there is one, we’ll deal with it.”

“Yes sir,” I said and sat down. It looked like it was my day for getting into fights. Well, I’d had a lot of new experiences since Dad shot himself.

“I looked for you at Petersburg Chandlery,” Leary said mildly. “They told me you didn’t work there any more?”

“The owner’s son-in-law took a swing at me,” I said. “I swung back. It escalated a bit, but I think the medicomp will have him fit for work in a day or two. As fit as Cady ever was.”

I grimaced. “Fritzi wouldn’t have cared about explanations, so I didn’t give him one. Besides—”

I managed a smile. “No excuse, sir.” The Academy answer.

Leary grinned. “Which is another thing I was wondering about,” he said. “You dropped out at the start of your third year. Your grades were all right. What was the problem?”

He wasn’t supposed to know my grades, but I don’t guess it’d been very hard to learn.

Hogg brought a tray over to the table. He filled one of the mugs and said, “I’ll stand here for a bit.”

He stood at the end of the table. His right hand was in his pocket. He sipped from the mug in his left, his eyes following every movement in the bar.

Leary filled the other two mugs and slid one to me. I said, “The problem was that my father had been cheating systematically on large contracts with the Ministry of Defense. When this was uncovered, he committed suicide. All our accounts were frozen. I dropped out of the Academy because I had to earn a living.”

It wasn’t quite that simple. I might’ve been able to manage living expenses, but my dad wasn’t just a crook: He’d been stealing from the RCN. I’d have been shunned in the Academy—if I’d been lucky. Chances were good that my fellow cadets would’ve beaten me to a pulp every night until I resigned.

“Umm,” Leary said as I tasted my beer. “People have been accused of things that aren’t true, you know? There was a reshuffle in the Ministry of Defense not long ago.”

“Yes, sir, that’s true,” I said. I drank more beer, because my throat was starting to choke up and I hoped swallowing would help. “But I went over Dad’s private accounts. I don’t know what the inspectors will be able to prove—they won’t see Dad’s files, I’ll tell you that. But the allegations were true.”

This wasn’t stuff I liked to talk about, and it wasn’t any of Leary’s business that I could see. Telling him to shut up was within my rights—and would’ve been, even if he’d been my commanding officer.

But that would look like I was afraid to talk about it. I wasn’t. Talking tore me up, but better that I say things myself than that other people say them about me.

Leary refilled my mug. Hogg kept lifting his beer to his lips while he watched the door, but the level in his mug didn’t seem to go down.

“What are you going to do now?” said Leary as he poured for himself.

“There’s other chandleries than Petersburg,” I said. That was the truth, but the confidence I tried to put in my voice was a lie. “And other work than that too, I guess.”

Leary shrugged. He raised his eyes to meet mine. “All true,” he said. “And you know my wife. Known her longer than I have, from what Mon says.”

“Well, I’ve known Miranda for pretty much my whole life,” I said, wondering if this was what Leary had been getting around to the whole time. All the stuff about my background didn’t matter to him as far as I could see. “I don’t think I’ve seen her since Junior, he was my older brother, got killed on New Harmony. He was Admiral Ozawa’s flag lieutenant. Junior and Tim Dorst had been best friends, and the families got together even after Dad got rich and Captain Dorst had pretty much his pay to live on. And then he died.”

Mom would’ve been happy to cut Miriam Dorst then because Miriam wasn’t willing to play poor relation to her. Dad wouldn’t have that. He’d been a great father and a good man—until the Navy Office looked into his accounts. Even then, thinking back, I couldn’t have had a better dad.

Leary filled my mug again and said, “Hogg? We could use another pitcher.”

“I shouldn’t be drinking this much,” I said. “I need to get up early to look for work.”

“This beer isn’t strong enough to hurt you,” Leary said, smiling at me as he poured the rest of the pitcher into his mug.

I wasn’t sure that was true—Junior’d been a hell-raiser, a proper RCN officer, but I wasn’t. The beer was going to my head.

Still, chatting with somebody friendly felt awfully good. I hadn’t had anybody to do that with since it came out about Dad.

“Look,” I said, looking straight at Leary. “Dad probably greased the skids to get Tim Dorst into the Academy because Tim wanted it so much. Dad had a lot of influence before it hit the headlines. I remember him saying, ‘Young Timothy’s got what it takes. There’s more about being an RCN officer than sitting on your butt in a classroom.’”

“Your father was right,” Leary said as Hogg put the fresh pitcher down. “About Midshipman Dorst and about RCN officers generally.”

He looked at me and his smile was a little harder. “Did he help you get in also?” he said.

“He didn’t have to,” I said, maybe a little crisper also. “For me or for Junior either one. Junior wasn’t much for study, but you could go a ways without finding somebody smarter.”

It’d probably been the best result for Junior that he wasn’t one of the handful who got out of the Heidegger alive after the missile hit her on lift-off. He’d been the social one of us. Having all your friends pretend they didn’t see you would’ve been hard for him.

The gods knew it wasn’t easy for me, and I didn’t have any friends. Not really.

The bar was filling up, but nobody said anything more about where we were sitting. If Cabrillo had come in, he’d decided not to make an issue out of it.

“You were raised rich yourself,” Leary said. “You didn’t have a problem working for a ship chandler?”

I shrugged. Bloody hell, I’ve drunk most of this mugful too.

“It’s honest work,” I said aloud. “Cady was a prick, but I’ve met pricks before. I was hoping that Fritzi would let me start doing some of the inventory control—there’s nobody in the office who really knows how to use a computer. Maybe the next house will.”

“As it chances …” Leary said. He put his mug down with a bit of a thump. “I’ve got a slot for a junior officer myself. I’ve been asked to command a chartered transport carrying a Foreign Ministry delegation to Saguntum. Two of the officers who’d normally accompany me are staying in Xenos this time. One has a great deal of surgery and therapy yet to go before he’s really fit for duty, and his fiancée has taken an appointment in Navy Office while that’s happening.”

“Sir?” I said. I was choking again. I put my beer down. “I’d be honored. Greatly honored. Ah—this would be on your yacht?”

The Princess Cecile was almost as famous as Captain Leary himself. She’d been built as a warship, a corvette. She’d punched far above her weight every time she’d been in action, according to the stories at the Academy.

“Afraid not,” Leary said, smiling again. “The Sissie’s a little too conspicuous for this job, they tell me. Besides, there’s to be twelve in the delegation, which would be a tight fit on a corvette. You’ll be third officer on a standard transport, the Sunray. I’ll be bringing some of my regular crew along, though.”

“Sir, I’ll serve in any fashion you and the Republic wish,” I said. I was choking, I knew I was, and I rubbed my eyes to keep from embarrassing myself even worse. “Ah, I was good academically, but I wasn’t at the top of my class even there.”

“I know exactly where you were, Olfetrie,” Leary said. “My wife asked me to do a favor if it looked reasonable, which it does to me. And Woetjans, my bosun, said she liked the way you handled yourself in a fight. She’s a pretty good judge of that sort of thing.”

My mug wasn’t empty, but he filled it anyway. “Now drink up,” he said. “You can report to the Sunray in Harbor Three at noon and we’ll get the paperwork squared away.”

I drank deeply. Tears were running down my cheeks. I decided I didn’t care.

Chapter Three

Captain Leary had said “noon.” I timed it to arrive at eleven in the morning. If they told me to cool my heels for an hour, that was fine. I wasn’t going to take a chance on being late, though.

My room was near Harbor Two, the main harbor for Xenos. It got most of Cinnabar’s commercial traffic and was the logical place for ship chandleries to cluster.

Harbor Three was the naval harbor, a long run by tram. There were water taxis too, but they wouldn’t have been much quicker and they cost more than I wanted to spend anyway. I punched HARBOR THREE on the call plate—it was one of the preloaded destinations—and a tram arrived within ninety seconds. There were already two men and an old woman with a grocery bag aboard.

The woman and a man got out as we snaked along the shoreline. Seven more people got on; two stood though there were eight seats. The car passed stops from then on. It could take the weight of twelve average passengers, but eight was the normal load.

For some of the way the pylons supporting the overhead track were sunk into marsh. There might have been interesting wildlife to see if the windows hadn’t been so scratched and smudged. I wasn’t in a mood to sight-see anyway.

We all got out when the car arrived at Harbor Three. There were at least a dozen tram stops at Harbor Two but there was only one here, and there were armed guards besides. They didn’t look too worried—they weren’t even checking IDs. It had probably been different before the Treaty of Amiens and the end of the long war with the Alliance of Free Stars.

I’d been to Harbor Three a couple of times while I was at the Academy, but I didn’t know the layout—let alone where the Sunray might be berthed. They’d have the information in Harbor Control, but before walking over there I called to the Shore Police guards, “Can any of you tell me where the Sunray is?”

“You want the Sunray?” said a voice behind me. “Thirty-seven A, but come with me ’cause I’m going there myself.”

I nodded to the guards and turned. The woman who’d spoken had been on the tram with me. She was short and fit-looking and spoke with a Xenos accent.

“Thank you, mistress,” I said. “I have plenty of time before I’m due, but I’d rather not spend it walking up and down the waterfront.”

We started off to the right. She walked like a spacer, balancing an instant before taking the next step in case the motion of the deck had changed.

“Are you a suit?” she said, looking at me hard. “You’re dressed like you belong here, but you sure don’t sound like it.”

She might’ve meant my accent, but I suspected it was the fact I was polite. Which would be regrettable, but I’d realized long before my current troubles that quite a lot of things were regrettable but true.

“I’m not a suit,” I said. “Captain Leary offered me the third officer’s slot on the Sunray.”

“You know Six?” the woman said. “Well, hell, I guess you’re the real thing, then. I’m Wedell; I’m a rigger in the port watch.”

“I’m Roy Olfetrie,” I said. I didn’t offer to shake hands because I was about to become her superior officer. “Yesterday I was working for a ship chandler, but I was fired.”

“Fired for what?” Wedell said, her expression getting minusculely less friendly. It was a reasonable question to ask a man who might shortly be giving you orders.

“For punching back when the owner’s son-in-law swung at me,” I said. “I’d do the same thing if it happened again.”

Wedell laughed hard. “I shoulda figured it was something like that!” she said. “Six isn’t one to screw up when he’s picking officers.”

“I’ll hope not,” I said. I smiled but I wasn’t as sure of that as Wedell sounded. “If I may ask—by Six you obviously mean Captain Leary. But why?”

“Oh, it’s his call sign,” Wedell said. “The XO is Five. That’s Lieutenant Vesey usually, but she’s staying on the ground this time. Master Cazelet got his leg next thing to shot off and she’s staying close. Vesey’s good, a hell of an astrogator and shiphandler, but you know—when you’re really in the shit and everybody’s shooting at you, there’s nobody like Six to have on the bridge.”

From the stories at the Academy, having Captain Leary on the bridge was a pretty good way to be sure that everybody would be shooting at you. Still, that was the whole point of there being a Republic of Cinnabar Navy. If it was always peaceful, I’d have joined the merchant service—or maybe taken a job in one of Dad’s ventures.

I’d never wanted to do that, which turned out to be a blessing. If I hadn’t been so obviously unconnected with Dad’s business, somebody—a private prosecutor if not the Solicitor of the Navy—would sure have gone after me months ago.

“Here’s Thirty-seven,” Wedell said, gesturing. “And that’s the Sunray in Berth A. I can’t tell you anything about her because we all just mustered aboard.”

Thirty-seven was a repair dock. The slip could be drained, but it hadn’t been for this job. The interior of a midsized freighter was being rebuilt extensively enough that at least three hull plates had been removed, though one of them was being welded back in place now.

“They’re adding two levels of bunks to the forward hold,” Wedell said. “We’re boarding a crew of eighty-odd, they tell me. There’s only accommodations for thirty-five normal-like. And amidships is all suites now.”

Thirty-five would be ample crew for a two-ring freighter. Leary was famous for making fast passages, which worked ships and rigs hard and worked their crews even harder. The Sunray would look like an ordinary fast freighter, but she’d have the crew for quick runs and quick repairs.

“They expanded the arms locker too,” Wedell said with a note of pride. “We’ve got no missiles and just the one cannon in the bow, but I guess we’ll be able to take care of ourselves on the ground if it comes to that.”

“I guess I’d better report aboard,” I said. I was feeling a little queasy. I wasn’t afraid of getting shot, but there were so many ways I could screw up leading ground troops. I hadn’t been trained for it.

But ground combat wasn’t part of the Academy curriculum, so even if I’d graduated as a midshipman it wouldn’t help. Master Cazelet, the officer I was taking the place of, wouldn’t have had any more training than I had. And he’d done well enough to get his leg shot off.

I grinned. Maybe I’d be luckier and take a bullet through the head. That would solve all my problems.

I headed for the boarding hatch but Wedell pointed to the balanced pair of freight elevators and said, “You’ll need to sign in on Level One so you may as well ride since we’re in dock.”

I didn’t want to look like a wimp, but panting after I’d climbed sixty feet of polished steel treads didn’t sound like a good start for meeting my fellow officers. I took the rigger’s suggestion and waved goodbye from the elevator platform. The elevators didn’t have cages, just six-inch railings to keep pipes from rolling off.

I threw the lever from left to right and started trundling upward immediately, though we stopped a quarter of the way up for half a dozen workmen get onto the car balancing mine. They were going off-shift, carrying personal tools and the jackets they’d worn when they came on duty in the wee small hours. The cars began to move again; the workmen and I nodded as we passed in opposite directions.

I got to the top level and starting going back down before I realized that there wasn’t an automatic stop. I threw the lever left and the car juddered to a stop. Another clump of workmen were trotting along the walkway from the ship’s uppermost level. I let them get past me before going the other way.

The walk had no railings either. I’m not particularly afraid of heights, but the crew leaving work was tired and in a hurry to get other places. I didn’t need to argue right-of-way with them.

Entry to bridge level was at a hatch which normally would have been torso height. The yard crew had cut it into a full-length door; the piece of hull plating lay in the rotunda beyond. They’d even attached temporary handholds to the plate, making it easier to handle.

I supposed they’d weld it back on when they were finished. I wondered if they’d fish the piece as well. In my three months at the chandlery I’d seen a lot of shortcuts to keep ships working—safely and otherwise. The “otherwise” versions made me gasp, but it was part of my education to learn that the real world wasn’t always what I’d been taught that it should be.

The forward rotunda held the suit lockers, the up and down companionways, and an airlock. A corridor ran sternward to my left and to the right was an open hatch. I could see the bridge beyond. I stepped into the hatchway, rang my knuckles on the transom, and called loud enough to be heard over the sound of hammering on steel below, “Master Olfetrie reporting as ordered!”

Three or four people were on the bridge, mostly at flat-plate displays. That was a lot more instrumentation than I expected to see on a merchant ship. I figured more than bunks were being added for this mission.

The man at the console in the far bow turned on his couch and gestured me to him. He wore RCN utilities but wore the saucer hat of an officer.

A woman was at one of the stations, but she was working on a personal data unit with a holographic display; it was a blur of color to me and everybody else except the user. On a jump-seat bolted to the hull beside her was another woman with an attaché case on her lap. The man on a port-side display seemed to be running a gunnery program.

I hadn’t noticed what the Sunray’s armament was: a single four-inch plasma cannon was more or less standard for a well-found freighter as anti-pirate defense, but I’d never been aboard a civilian ship in which anybody really cared about gunnery—until they had to use the weapon.

“I’m Cory,” the officer at the command console said when I knelt beside him. “I’m second lieutenant and have the duty right now. You are?”

“Sir, I’m Roylan Olfetrie,” I said. “Captain Leary visited me last night and ordered me”—that wasn’t really the right word—“to report at noon today to be signed on as the Sunray’s third mate.”

“Go sit at the striker’s seat so we can hear each other over whatever the yard’s doing,” Cory said, gesturing me to the seat on the opposite side of the console. It was where a junior striking for a position could watch the regular officer and even control the ship if the senior spacer permitted. They were standard in naval use but much less common on civilian vessels.

I settled myself. Cory must have engaged the active cancellation field, because the ambient noise shut off. The small flat-plate display at this position showed Cory’s face. He said, “Six told me you’d be coming aboard. Welcome to the Sunray. You’re no newer to her than all the rest of us are, but I guess we’re new to you. The rest of us have been together quite a while, on various of Six’s commands.”

“I’ll try to fit in,” I said. “Anyhow, I’ll do my job the best I know how to.”

“You’ll be covering Master Cazelet’s duties,” Cory said. “Do you know anything about commo?”

“What?” I said. “Well, I’ve had a unit on it but I don’t have any experience. Was Cazelet the commo officer of, of the Princess Cecile?”

“No, that’s Officer Mundy,” Cory said with a grin that implied more than humor. “She’ll have the job here too. But it’s a handy skill and Rene was good at it.”

He grinned more broadly. “Almost as good as I am,” he said.

“I’ll try to learn,” I said. It was all I could figure to say.

“Astrogation?” Cory asked.

“I had two years in the Academy,” I said. “I—”

“Academy?” said Cory, cutting me off. “Why did you leave?”

“Family problems,” I said. I swallowed and added, “My dad was a crook. I’m not. I guess he isn’t now either, because he shot himself.”

Cory didn’t say anything for a moment, just held my eyes. Then he said, “Well, that’ll do for a reason, I guess.”

“I got good grades,” I said, switching back to a subject I preferred. “But I left before my senior cruise.”

“Marksmanship?” Cory said.

“Personal weapons in my second year,” I said. “I didn’t try out for a shooting team—it seemed to me I couldn’t do the practice I’d need and keep up my studies.”

I thought for a moment and added, “Dad had a trap range on his estate in Oriel County. I used it the last few summers and got pretty good.”

“That could be handy,” Cory said, though I couldn’t imagine how. I was—or anyway I wanted to be—a naval officer, not a sporting gentleman. He looked up from his display—the console was obviously transcribing the interview—and said, “Ever kill a man?”

“No, sir,” I said, as though the question hadn’t shocked me. “Is that a job requirement?”

“Sometimes it is, yes,” Cory said. “Rene never got his … conscience, I suppose, past that, though. He was a bloody good officer and bloody good friend.”

There might have been a challenge in the way he put that. I ignored the possibility and said, “I’m sorry he was injured, sir.”

Cory smiled again. “Yeah,” he said. “So am I, but sometimes that comes with the job too.”

He stretched, spreading his arms. “I’ve assigned you to the port watch,” Cory said. “You’ll be under Lieutenant Enery for the time being, but chances are you’ll take over if you work out. Six said you were to be worked like a midshipman in training, and so you shall be.”

I cleared my throat. I said, “Thank you, sir. I’ll fetch my baggage and report back aboard.”

I didn’t have to worry about housing next week after all. I think Mistress Causey would miss me: I was quiet and didn’t come back drunk and singing at three in the morning. And she didn’t have to worry about getting the rent on time—if I had the money, and for rooming houses like hers I wasn’t the only resident who might find himself out of a job at the end of the week.

“Oh, Six also said you were to draw an advance of a hundred florins if you wanted it,” Cory said, raising an eyebrow to make a question of his statement.

“Ah …” I said, thinking about what I had in pawn. Most of it I’d never need again, but—

“If I could have fifty florins,” I said, “that would be useful for getting an outfit together. At the moment I’ve got the clothes I’m wearing, and another set like them.”

Cory reached into his belt purse and placed a fifty-florin coin on top of the console. “We’re not set up to run you a credit chip the normal way yet,” he said. “I’ve got it noted on your records here and I’ll get it back on payday.”

“Thank you, sir,” I said. It struck me that the Sunray operated in a very easygoing fashion, and also that Cory was a lot less concerned about fifty florins than most young lieutenants would be. I wondered if he had family money.

“Before you go, Olfetrie …” Cory said. He gestured to the woman working on her personal data unit. “Go over and talk to Officer Mundy, will you? She’ll have some questions.”

“The signals officer?” I said. I thought I must’ve misheard.

“Yeah, she’s that,” said Cory, “but she’s a bit more than that too. Among other things, she’s a good friend of Captain Leary; his best, maybe. And Olfetrie?”

“Yes,” I said. Captain Leary’s job offer still seemed like the best thing that’d happened to me since Dad had shot himself, but there was a lot more to it than I’d have learned in my final two years at the Academy.

“If Officer Mundy tells you to do something, do it,” Cory said. “Don’t worry about rank—because believe me, she doesn’t. And don’t argue if you think she’s wrong, because I don’t remember that happening. Just a friendly suggestion, of course.”

“Thank you, Cory,” I said and got up. This was all bloody crazy and I didn’t begin to understand, but I actually believed Cory about it being friendly advice.

I walked over to the signals officer and knelt beside her station, as I’d done with Cory. “Officer Mundy?” I said in a lull in the racket of impact wrenches. “I’m Third Officer Olfetrie reporting to the Sunray. The OiC suggested that I speak to you.”

Mundy said nothing for a moment. She was using short wands to control her data unit. I’d heard of them—they were supposed to be quicker than any other input method if you were good enough—but they required a delicacy of control and pressure beyond that of anybody I’d ever met.

I thought Mundy was just too busy to respond for the moment, but then the woman in the jumpseat beside her reached through the holographic display, disrupting it. Mundy looked up and focused on me with a terrifying, blank expression.

Her face relaxed, though I wouldn’t call her expression welcoming. “Ah,” she said, twitching her wands again.

The bridge had gone quiet again. Mundy had switched on a cancellation field. These were part of a navigation console, but I’d never heard of one being attached to a subordinate display.

“I’m glad you came over, Olfetrie,” Mundy said. “I have a few background questions beyond what Cory would have asked.”

“All right,” I said, standing up again. I was going along with this, but I won’t pretend I was happy about being questioned by a junior warrant officer.

“What are your politics?” Mundy said.

She could have asked me my favorite color and not surprised me as much. I said, “I don’t have any politics. I’ve never voted, and I don’t remember my parents ever voting, though I can’t swear they didn’t. We weren’t a political family.”

“Your father was Dean Olfetrie?” said the clerk. A clerk, for hell’s sake! “I’d say he was pretty political.”

I looked at her and regretted it. The clerk vanished into the background unless you focused on her. When I did that, I’ve seen guard dogs with warmer expressions.

“Openly political,” I said, as calmly as I could manage. “My father bribed politicians, yes. I do not, nor did my brother before he was killed aboard the Heidegger. At present—” I fingered the coins in my pocket. “I’ve got eighty-two florins and change. That would probably allow me to bribe a dog warden to release my pet, but I don’t think it would go much beyond that.”

I glared at the clerk. To my amazement she smiled back. She said, “Good answer, kid.”

Mundy, looking at her display again, said, “You mentioned family, Olfetrie. What kin have you?”

I shrugged. It was disconcerting to be interviewed by someone who didn’t bother to look at me. “My mother’s probably still alive,” I said, “though I couldn’t tell you more than that. She disappeared when the bailiffs arrived, and I haven’t tried to find her. Mom … got very full of herself when Dad was important. I guess the scandal bothered her even more than it did me.”

Though probably not for the same reasons. I’d been pretty much my dad’s son.

“My brother’s dead and I don’t have any other siblings,” I said. After thinking for a moment, I added, “Miriam Dorst is my mother’s cousin. She and her daughter Miranda are probably my closest living relatives.”

Mundy didn’t look up or even nod. She said, “Do you have a girlfriend? Or boyfriend.”

“I did, a girlfriend,” I said, thinking about Rachel. “Before Dad shot himself. Pretty much everybody I knew dropped me then. Certainly she did. So no, not now.”

Looking up at last, Mundy said, “The Sunray is carrying a diplomatic delegation, Olfetrie. That makes political neutrality for our officers more than usually important.”

I smiled. “I was training to be an RCN officer,” I said. “The political neutrality requirement wasn’t one of those I expected to have trouble with.”

“Thank you, Olfetrie,” Mundy said, going back to her data unit. “I don’t have any further questions. I hope our association goes well.”

I left the bridge. At least I had more to think about than wondering if I’d be able to carry out the duties of a junior officer on a civilian vessel.

Chapter Four

I had a cabin on Level 1—the rebuilding had added officers’ spaces as well as quarters for the crew and passengers. I had just opened the hatch to stow away the gear I’d brought, mostly retrieved from pawn, when the cabin across the corridor from mine opened.

“You’re Olfetrie?” said the small woman who stuck her head out.

“Yes, ma’am,” I said. “I’m the third mate.”

“I’m Enery,” she said. The right side of her face had a glassy perfection and moved very little when she spoke. “Come over and have a drink when you’ve got that”—she nodded at the bundle of my belongings—“struck down.”

She gave me a smile that would’ve been less grisly if both sides of her face worked. She added, “Don’t worry. I don’t have designs on your body.”

I stowed my gear in the cabinet under the bunk—which, with the small desk/chair combination on the corridor bulkhead beside the hatch, was all the furniture there was. That done, I stepped across and knocked on the first officer’s hatch. She called, “It’s open.”

Her cabin was twice the size of mine—that didn’t make it big—and there was a flat-plate display on the hull-side bulkhead. Two chairs were bolted to the deck on the corridor side and another at the display.

Enery was straddling the chair by the display. She poured whiskey into a tumbler, then handed the bottle to me. “There’s another glass under the chair seat,” she said, gesturing with her own drink.

I took the tumbler—it was high-density plastic—from its nest with flatware and a platter and sat down to pour. The whiskey was a Heilish County brand, a very good one that one of Dad’s friends had sworn by—but it was something of an acquired taste for its heavy smokiness. It wasn’t a favorite of mine, but I sipped.

I handed the bottle back and said, “Thank you, mistress.”

“We’re the outsiders on this run, Olfetrie,” Enery said. I noticed that the back of her right hand was hairless and had the same smoothness as half her face. “I thought we ought to get to know one another.”