8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

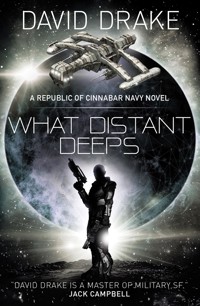

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: The Republic of Cinnabar Navy

- Sprache: Englisch

David Drake [is] the reason a lot of people got started reading military science fiction, because it's always a good idea to start with the best.--David WeberThe jackals are moving in! The barbarians of the outer reaches intend to play both Cinnabar and Cinnabar's sworn enemy, the totalitarian Alliance, against each other and bring both empires down like an enormous house of cards. The barbarian pirates have commandeered and hot-rodded starships that can outmaneuver even Captain Leary's trusty RCN corvette. But speed and tech don't count for everything. The Princess Cecile has the incomparable Daniel Leary and his trusted aide and friend Adele Mundy in command. Faced with such grit, bravery and intelligent misdirection the pirates might find they've bitten off more than they can chew.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 658

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Also by David Drake and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

ALSO BY DAVID DRAKE AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

THE REPUBLIC OF CINNABAR NAVY SERIES

With the Lightnings

Lt. Leary, Commanding

The Far Side of the Stars

The Way To Glory

Some Golden Harbor

When the Tide Rises

In the Stormy Red Sky

What Distant Deeps

The Road of Danger (October 2018)

The Sea Without a Shore (January 2019)

Death’s Bright Day

Though Hell Should Bar The Way

Redliners (April 2019)

THE REPUBLIC OF CINNABAR NAVY

DAVID DRAKE

TITAN BOOKS

What Distant Deeps

Print edition ISBN: 9781785652332

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785652349

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First Titan edition: July 2018

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2010, 2018 by David Drake. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:

www.titanbooks.com

To Jason Williams and Jeremy Lassen of Night Shade Books

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I’ll start out with what in my days as a lawyer we would call boilerplate: I use both English and metric weights and measures in the RCN series to suggest the range of diversity which I believe would exist in a galaxy-spanning civilization. I do not, however, expect either actual system to be in use in three thousand years. Kilogram and inch (et cetera) should be taken as translations of future measurement systems, just as I’ve translated the spoken language.

I really wish I didn’t have to say that. I’ve learned that I do.

The situation on which I based the plot of What Distant Deeps is the crisis that overtook but did not—quite—overwhelm the Roman Empire in the third century A.D. The extremities of the empire went through striking (and strikingly different) convulsions. For the action of this novel I’m particularly indebted to what happened in the East, but there is by no means a direct correspondence between this fiction and historical reality (even to the extent that we know the reality).

I write fiction to entertain, not to educate; but Aristophanes proved it was possible to do both, and on a good day a reader might learn something from me as well. Empires have generally used proxies to fight wars on their borders. The problem—as Rome learned with the Oasis of Palmyra—is that the proxies have policies of their own. Not infrequently, things go wrong for the principal when the proxy decides to implement its separate policies.

For a recent example, in the 1970s the US hired a battalion of troops from Argentina, called them “the Contras” and employed them to fight the socialist government of Nicaragua. The military dictatorship running Argentina at the time was more than happy to support the US effort.

Unfortunately for everybody (except ultimately the Argentine people), General Galtieri and his cronies (some of whom, amazingly, were even stupider and more brutal than he was) decided that their secret help to the US meant that the US would protect them from Britain when they invaded the Falklands and subjected the islands’ English-speaking residents to what passed for government in Argentina. Galtieri was wrong—the tail didn’t wag the dog during the Falklands War—and Argentina ousted the military junta as a result of its humiliation by Britain; but there might not have been a Falklands War if the US had not used Argentina as a military proxy in Nicaragua.

I could mention cases where US proxy involvements have led to even worse results. If the shoe fits, wear it.

Finally, a word about the dedication. I could simply let it stand (I’ve many times dedicated a book to an editor or publisher), but there’s an aspect to this one that won’t be obvious to anyone outside my head (including Jason and Jeremy).

I came back to the World in 1971 and began writing the Hammer stories as a way of dealing with my experiences in Vietnam and Cambodia. The stories were successful, but they made me a pariah to a number of very vocal people.

Jason took me aback when he approached me about putting the series in limited-edition hardcovers. Nobody had ever suggested the stories were worthy of that before. Indeed, the people who said anything were likely to be protesting them being in print at all, even in mass market editions.

When I opened the box that contained the beautifully produced Complete Hammer’s Slammers, Volume 1, I had an unexpected emotional reaction: I’d finally come home to the America which sent me to Nam in 1970. It was something that I didn’t know I’d been missing until Night Shade Books gave it to me.

—Dave Drake

david-drake.com

In what distant deeps or skies

Burned the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand dare seize the fire?

—The Tyger

William Blake

CHAPTER 1

THE BANTRY ESTATE, CINNABAR

“Come and join, Squire Daniel!” called a dancer as she whirled past. “I’m not partnered!”

Daniel vaguely recalled the face, but he knew he must be thinking about an older sister. Ten years ago, he’d left Bantry to enter the Republic of Cinnabar Naval Academy. This girl was no more than sixteen, though she was undoubtedly well developed.

Mind, he didn’t recall the sister’s name either.

Steen—Old Steen since the death of his father, who’d been tenant-in-chief before him—elbowed Daniel in the ribs and said, “Haw! Not just a dance she’s offering you, Squire! Going to take her up on it? You always did in the old days!”

Steen’s wife was hovering nearby, though she hadn’t presumed to enter the group of men centered on Daniel and the cask of beer on the sea wall. Foiles, the commodore of the fishing fleet, and Higgenson, the manager of the estate’s processing plant, were from Bantry, like Steen, but also present were the owners of three nearby estates who had come to the festivities. Waldmiller of Ponds was over seventy and Broma of Flattler’s Creek wasn’t much younger; but at twenty-five, Peterleigh of Boltway Manor was a year Daniel’s junior.

Before Daniel could pass off the comment with a grin and a shake of his head, Mistress Steen clipped her husband over the ear with a hand well used to hoeing. Fortunately Steen hadn’t gotten his earthenware mug to his lips, so he merely jerked the last of his ale over his bright purple shirt instead of losing his front teeth.

“Where’s your manners, you drunken old fool?” Mistress Steen demanded in a voice that started loud and gained volume. “Can’t you see Lady Miranda close enough to spit on? You embarrass yourself and you embarrass the Squire!”

Daniel caught Mistress Steen’s hands in his own, partly to forestall the full-armed follow-up stroke she was on the verge of delivering. “Now, Roby!” he said. “My Miranda’s a sensible woman who wouldn’t take note of a joke at a celebration, or even—”

He bussed Mistress Steen on the cheek. It was like kissing a boot.

“—this!” he concluded, stepping away.

“Oh, Squire!” Mistress Steen gasped in a mixture of delight and embarrassment. She put her hand to her cheek as though to caress the memory.

“Oh, you do go on!” she said as she stumped off, seemingly half-dazed. Daniel thought he heard her titter when the piping paused.

The original piper, gay in a green vest with blue and gold tassels, was snoring in a drunken stupor behind the bench. His son—who couldn’t have been more than twelve—was making a manful effort to replace him. All the will in the world couldn’t increase the boy’s lung capacity.

Daniel’s eyes touched Miranda, who was with her mother Madeline a good twenty yards away—Roby Steen had been exaggerating. She waved with a merry smile, then went back to describing the stitching of her bodice to more women than Daniel could easily count.

The wives of the neighboring landowners were there, but Bantry tenants made up most of the not-quite-crush. The tenants observed protocol in who got to drink with Daniel, but their wives and daughters weren’t going to give way to outsiders from other estates at their first chance to meet the Squire’s lady.

“A pretty one, Leary,” Peterleigh said. “Your fiancée, is she?”

Daniel cleared his throat. “Ah, Miranda and I have an understanding,” he said, hoping that his embarrassment didn’t show. “There’s nothing formal at this moment, you’ll understand, until, ah, some matters have been worked out.”

Miranda herself never raised the question. She was an extremely smart woman, smart enough to know that others would prod Daniel regularly.

“For the gods’ sakes, boy,” Waldmiller said with a scowl at Peterleigh. “If you weren’t raised to have manners, then at least you could show enough sense to avoid poking your nose in Speaker Leary’s affairs, couldn’t you?”

Peterleigh could probably buy and sell Waldmiller several times over, but seniority and the words themselves jerked the younger man into a brace. “Sorry, Leary, sorry!” he said. “Don’t know what I was thinking, asking about a fellow’s private affairs. Must’ve drunk too much! My apologies!”

Bringing up Daniel’s strained relationship with his father was calling in heavier artillery than Peterleigh deserved, but the young man could have avoided the rebuke by being more polite. Corder Leary was one of the most powerful members of the Senate—and certainly the most feared member. He hadn’t visited Bantry since Daniel’s mother died, and Peterleigh—who was both young and parochial—had obviously forgotten who the estate’s real owner was.

“Not at all, Peterleigh,” Daniel said, smiling mildly. “But as for drinking, I think it’s time for me to have another mug of our good Bantry ale. It’s what I miss most about Cinnabar when the RCN sends me off to heaven knows where.”

So speaking, he stepped to the stand beside them where a ceramic cask of ale and a double rank of earthenware mugs waited. He knew his neighbors—Bantry’s neighbors—would be surprised at having to pump their own beer, but Daniel was providing a holiday for all the Leary retainers.

He’d thought of bringing in outside servants, but city folk would mean trouble. One of them would sneer at a barefoot tenant—and be thrown off the sea wall, into the Western Ocean thirty feet below.

Daniel was dressed more like a countryman than a country gentleman, but he was wearing shoes today. He generally wouldn’t have been at this time of the year when he was a boy on Bantry.

A pair of aircars landed in quick succession, drawing the men’s attention. “That’s Hofmann in the blue one,” Broma said. “I don’t recognize the gray car though.”

“I think that’s … ,” Daniel said. “Yes, that’s Tom Sand, the contractor who built the Hall. I, ah, invited him to the dedication.”

Broma squinted at the limousine which was landing a hundred yards away, on the field of rammed gravel laid for the purpose beside the Jerred Hogg Community Hall. “That’s quite a nice car for … ,” he began.

He stopped and turned to Daniel in obvious surmise. “You don’t mean the Honorable Thomas Sand of Archstone Construction?” he said. “By the gods, Leary, you do! Why, they’re one of the biggest contracting firms in the whole Capital Region!”

“They did a fine job on the Hall,” Daniel said with a faint smile, turning to look at the new building itself. All four sides had been swung onto the roof as they were designed to be, turning the building into a marquee. The drinks—no wines or liquor, but ale without limit—and the food were inside, where Hogg was holding court.

Hogg had been the young master’s minder when Daniel was a child, and his servant in later years. He’d taught Daniel everything there was to know about the wildlife of Bantry which he and his ancestors back to the settlement had poached. He’d taught Daniel many other things as well, much of it information which would have horrified Daniel’s mother, who was delicate and a perfect lady.

Hogg had a tankard of ale and a girl half his age ready with a pitcher to refill it. His arm was around a similar girl, and as many tenants as could squeeze close were listening to his stories of the wonders he and the young master had seen among the stars. Daniel was probably the only man present who knew that the wildest stories were absolutely true.

Hogg was royalty in Bantry today. Daniel smiled faintly. That was a small enough payment for the man who’d taught the young master how to be a man.

Tom Sand walked toward Daniel in the company of half a dozen children including at least one girl. They could claim to be guiding Sand, but they were more concerned with getting a good look at a stranger who was an obvious gentleman. Sand had weather-beaten features and more chest than paunch, but his suit—though gray—shimmered in a way that neither wool nor silk could match. Daniel suspected it had been woven from the tail plumes of Maurician ground doves.

“You’ll be spending more time in Bantry now that we’re at peace again, Leary?” Waldmiller asked, letting his eyes glance across their surroundings. His tone was neutral and his face impassive, signs that he was controlling an urge to sneer. This was a working estate, not a showplace.

They stood in the middle of the Bantry Commons, a broad semicircle with the sea front forming the west side. The shops bounded its south end and the sprawling manor was to the north; tenant housing closed the arc. The dwellings facing directly on the common were older, smaller, and much more desirable than the relatively modern units in the second and third rows. Younger sons and their sons were relegated to the newer housing.

Instead of turning the manor into a modern palace to reflect the family’s increased wealth and power, Daniel’s grandfather had put his efforts into a luxurious townhouse in Xenos. Corder Leary had visited Bantry only as a duty—and not even that after the death of his children’s mother. The house looked much as it had three centuries ago.

Birds screamed overhead. The fish processing plant was shut down for the celebration, and they were upset at missing their usual banquet of offal.

Daniel grinned. At that, the flock wasn’t much less musical than the piper … and there’d been enough ale drunk already that the dancers could probably manage to continue even if the boy on the bagpipe gave up the struggle he was clearly unequal to.

“It’s true that many ships have been laid up since the Truce of Rheims,” Daniel said, “and that means a number of officers have gone on half pay.”

In fact almost two thirds of the Navy List had been put on Reserve status. That meant real hardship for junior officers who had been living on hopes already. Those hopes had been dashed, but they were still expected to have a presentable dress uniform to attend the daily levees in Navy House which were their only chance of getting a ship.

“But I’ve been lucky so far,” Daniel continued. “I’m still on the Active list, though I don’t have an assignment as yet. And anyway, I wasn’t really cut out to be a—”

He’d started to say “farmer,” but caught himself. Thank the gods he’d drunk a great deal less today than he would have even a few years earlier. Daniel hadn’t become an abstainer, but he’d always known when he shouldn’t be drinking; and the higher he rose—in the RCN and in society generally—the more frequent those occasions were.

“—a country squire.”

Sand joined them; the entourage of children dropped behind the way the first touch of an atmosphere strips loose articles from the hull of a descending starship. Miranda was leading Mistress Sand to the house, having shooed away a similar bevy of children.

Waldmiller opened his mouth to greet Sand. Peterleigh, his face toward the sea, hadn’t noticed the newcomer’s approach. He said, “Well, I think the truce is a bloody shame, Leary. You fellows in the navy had the Alliance on the ropes. Why the Senate should want to let Guarantor Porra off the hook is beyond me!”

“Well, Peterleigh … ,” said Daniel. “You know what they say: never a good war or a bad peace.”

“And maybe it was a good war for folks who live out here in the Western Region and don’t leave their estates,” boomed Thomas Sand, “but it bloody well wasn’t for anybody trying to make a living in Xenos. Off-planet trade is down by nine parts in ten, so half the factories in the Capital Region have shut and the rest are on short hours.”

Peterleigh jumped and would have spilled ale if he hadn’t emptied his mug. Waldmiller and Broma masked their amusement—Broma more effectively than his elder colleague. The tenants, Foiles and Higgenson, maintained their frozen silence. They’d been quiet even before Maud Steen had torn a strip off her husband, and that had chilled them further.

“Didn’t mean to break in unannounced,” Sand said. “I’m Tom Sand and I built the hall there.”

He nodded in the direction of it.

“And not a half-bad job, if I do say so myself.”

“These are my neighbors,” said Daniel. “Waldmiller, Broma, and you’ve already met Peterleigh, so to speak. Have some ale, Sand. We’re setting a good example for the tenants so that none of them bring out the kelp liquor they brew in their sheds.”

Sand laughed, drawing a mug of ale. “I understand, Leary,” he said. “I have a capping party for the crew on each job, but it’s beer there too. It doesn’t hurt a man to get drunk every once in a while, but I’d as lief give them guns as hard liquor for the chances that they’d all survive the night.”

He shook his head, then added, “No offense meant about trade being strangled. The RCN did a fine job. But any shipowner who lifted at all got a letter of marque and converted his hull into a privateer. In the neutral worlds, chances are he’s got warrants from both us and the Alliance. That was better business than hauling a load of wheat from Ewer to Cinnabar—and likely being captured by some privateer besides.”

“No offense taken, Sand,” Daniel said. “Every word you say is true.”

He swept his neighbors with his eyes. “You see, Peterleigh,” he said, “our tenants work hard and they live bloody hard by city standards. But they never doubt there’ll be food on the table in the evening, even if it’s dried fish and potatoes. The folk in the housing blocks around Xenos don’t know that, and I’m told there were riots already last year.”

He flashed a broad grin and added, “I wasn’t around to see them, of course.”

“Right!” said Sand, turning from the keg with a full mug of ale. To the others in the circle he said, “Captain Leary was chasing the Alliance out of the Montserrat Stars with their tails between their legs. Splendid work, Leary! Makes me proud to be a citizen of Cinnabar.”

“That’s the Squire for you!” blurted Higgenson, pride freeing his tongue. “Burned them wogs a new one, he did!”

There was commotion and a loud rattle from the Hall. Hogg and a tenant of roughly his age were dancing with rams’ horns strapped to their feet. The curved horns made an almighty clatter on the concrete floor, but the men with their arms akimbo were impressive as they banged through a measure to the sound of the bagpipe.

“That’s Hogg himself, isn’t it, Leary?” asked Broma. The hammering dance had drawn all eyes, though the tenants around the Hall limited what Daniel and his fellows could see from the sea front.

“Aye, and that’s Des Cranbrook who’s got a grain allotment in the northeast district and a prime orchard tract,” said Foiles. Since Higgenson had spoken without being struck by lightning, the fisherman had decided it was safe for him to say something also.

“Plus the common pasturage, of course,” Daniel said, speaking to Sand; his fellow landowners took that for granted. The dancers—both stout; neither of them young nor likely to have been handsome even in youth—hopped with the majesty of clock movements, slowly pirouetting as they circled one another.

“Haven’t seen a real horn dance in—law!—twenty years if it’s been one,” said Higgenson. His social betters were intent on the dancing, which gave him a chance to speak from personal knowledge. “The young folk don’t pick it up, seems like.”

“That’ll change now,” said Foiles. “The young ones, the ones that didn’t know Hogg before he went away with you, Squire—”

He dipped his head toward Daniel.

“—they all think the sun shines out of his asshole. And some of the women as did know him and so ought to know better, they’re near as bad.”

The dancers collapsed into one another’s arms, then wobbled laughing back to their seats. Girls pushed each other to be the ones unstrapping the rams’ horns. Cranbrook was getting his share of the attention. The lass hugging him and offering a mug of ale might have been his granddaughter, but Daniel was pretty sure that she wasn’t. He grinned.

“Ah … ?” said Higgenson in sudden concern—though he hadn’t been the one who’d actually commented on Hogg’s former reputation. “Not that we meant anything, Squire. You know how folks used to say things, and no truth in them, like as not.”

“I suspect there was a lot of truth in what was said about Hogg,” Daniel said, thinking back on the past and feeling his smile slip. “And about me, I shouldn’t wonder. It’s probably to Bantry’s benefit as well as the Republic’s that the RCN has found the two of us occupation at a distance from the estate.”

Georg Hofmann approached the group. He looked older and more stooped than Daniel had remembered him, but that was years since, of course. His estate, Brightness Landing, was well up the coast.

“I didn’t recognize the woman who got out of the car with Hofmann,” Daniel said in a low voice. She was in her early forties and had been poured into a dress considerably too small and too youthful for her.

“He remarried, a widow from Xenos,” said Waldmiller with a snort. “Damned if I can see the attraction.”

“And she brought a son besides,” said Peterleigh. “Chuckie, I believe his name is; Platt, from the first husband. That one might better stay in Xenos, I think.”

The youth was tall and well set up. He looked twenty from Daniel’s distance, but his size may have given him a year or two more than time had. Accompanied by two servants in pink-and-buff livery—those weren’t Hofmann’s colors, so they may have been Platt’s—he was sauntering toward a group of the younger tenants on the sea wall not far from the manor house.

Daniel’s eyes narrowed. Platt took a pull from a gallon jug as he walked, then handed it to a servant. His other servant held what looked very much like a case of dueling pistols.

Hofmann joined the group around Daniel. Up close, he looked even more tired than he had at a distance. He exchanged nods with his neighbors, then said, “It’s been years, Leary. Good years for you, from what I hear.”

“It’s good to see the old place, Hofmann,” Daniel said, “though I don’t really fit here any more, I’m afraid. Hofmann, this is Tom Sand, who built the new Hall.”

“I heard you were doing that work, Sand,” said Hofmann, extending his hand to shake. Hofmann was the other member of the local gentry who’d been active in national affairs; though not to the extent of Corder Leary, of course. “How did that come to happen, if I may ask. It’s not—”

He gestured toward the new building.

“—on your usual scale, I should have said.”

Daniel heard the low-frequency thrum of the big surface effect transport he’d been expecting and gave a sigh of relief. He’d set the arrival for mid-afternoon. He hadn’t wanted his Sissies to party for the full day and night with the Bantry tenants, but he’d been so long in the company of spacers that the rural society in which he’d been raised had become strange to him.

“I asked for the job,” said Sand, squaring his broad shoulders. “I wanted a chance to do something for a real hero of the Republic.”

He gave Daniel a challenging grin and a nod that was almost a bow. “Hear hear!” said Peterleigh, and the others in the group echoed him.

“Much obliged,” said Daniel in embarrassment. He drew a mug of ale for an excuse to turn away.

The bid for the Community Hall had seemed fair. Deirdre, Daniel’s older sister, had handled the matter for him; she’d been handling all his business since prize money had made that more complex than finding a few florins to pay a bar tab. Deirdre had followed their father into finance with a ruthless intelligence that would doubtless serve her well in politics also when she chose to enter the Senate.

The building that appeared wasn’t the simple barn that Daniel had envisaged, though. The wall mechanisms were extremely sophisticated—and solid: Daniel had gone over them with the attention he’d have given the lock mechanisms of a ship he commanded. Only then had he realized that this was more than a commercial proposition for the builder; as, of course, it was for Daniel Leary himself.

The transport rumbled in from the sea, a great aerofoil with a catamaran hull. It slid up the processing plant’s ramp—which had been extended north to support the starboard outrigger—and settled to a halt.

The reel dance had broken up for the time being. All eyes were on the big vehicle.

“This something you were expecting, Leary?” said Waldmiller, frowning. To him such craft were strictly for trade, hauling his estate’s produce to market in the cities of the east.

The hatches opened. Even before the ramps had fully deployed, spacers were hopping to the ground wearing their liberty suits. Their embroidered patches were bright, and ribbons fluttered from all the seams.

“Up the Sissie!” someone shouted. The group headed for the Hall and the promised ale with the same quick enthusiasm that they’d have shown in storming Hell if Captain Leary had ordered it.

“It is indeed, Waldmiller,” Daniel said. “These are the spacers who’ve served with me since before I took command of the Princess Cecile. I invited them and some of my other shipmates to share the fun today.”

Officers waited for the ramp, not that they couldn’t have jumped if they’d thought the situation required speed rather than decorum. For the most part they wore their second-class uniforms, their Grays, but Mon—a Reserve lieutenant, though he’d for several years managed Bergen and Associates Shipyard in Daniel’s name—had made a point of wearing his full-dress Whites.

The shipyard had been doing very well under Mon’s leadership. That had allowed him to have the uniform let out professionally, since his girth had also expanded notably.

Two slightly built women were the last people out of the transport. Adele wore an unobtrusively good suit, since she was appearing as Lady Adele Mundy rather than as Signals Officer Mundy of the Princess Cecile. Tovera, her servant, was neat and nondescript, as easy to overlook as a viper in dried leaves.

“I say, Leary?” said Broma. “Who’re the civilian women there? Your Miranda’s meeting them, I see.”

Miranda, accompanied by another flock of children—generally girls this time—waited at the bottom of the ramp. Mothers and older sisters were running to grab them when they noticed what was happening.

“That’s my friend Adele and her aide,” Daniel said with satisfaction. “And I’m very glad to seem them again!”

* * *

The transport had four files of seats running the length of the fuselage, arranged in facing pairs. Only when the exit ramps began to open did Adele shut off her personal data unit and slide it into the pocket which she had added to the right thigh of all her dress clothes. The cargo pocket of RCN utilities worked very well without modification.

Adele had found over the years that bespoke tailors gave her more trouble when she demanded the PDU pocket on civilian suits than RCN officers did when they saw her out of uniform. On the other hand, even the snootiest tailor gave in eventually for the honor of dressing Mundy of Chatsworth, a member of one of the oldest families of the Republic and a decorated hero besides.

Adele was in fact the only member of the Mundys of Chatsworth to have survived the Proscriptions which had decapitated the Three Circles Conspiracy nearly twenty years earlier. At the time she was a sixteen-year-old student in the Academic Collections on Blythe, the second world and intellectual capital of the Alliance of Free Stars. Though her family had been extremely wealthy, her personal tastes were simple. That fitted her to survive if not flourish in a poverty too deep to be described as genteel.

Recently, the prize money that had accrued to her as an RCN warrant officer in the crew of the most successful captain in a generation had allowed Adele to live and dress in a fashion that befit her rank in society. She was amused to reflect that she owed the recovery of her fortunes to the son of Speaker Leary, the man who had directed the execution of every other member of her family.

She stood; Tovera, with her usual neutral expression, waited in the aisle to precede Adele as soon as she decided to leave the transport. Tovera’s expression sometimes implied that the pale, slender woman was pleased about something. Those “somethings” weren’t the sort of matters that amused most other people, however.

Adele shared much of her servant’s sense of humor. That, and the fact that Adele was a crack shot whose pistol had killed indeterminate scores of people during her service in the RCN, made her a suitable role model for Tovera. In order to survive in society, a murderous sociopath needs someone to translate the rules of acceptable behavior for her.

Adele started down the aisle. Lieutenant Cory and Midshipman Cazelet were waiting by the hatch. Tovera gave them a minuscule nod which sent them down the ramp. This wasn’t a social event for Adele; at least not yet.

The two young officers were her protégés, though she wasn’t sure how that had happened. Rene Cazelet was the grandson of her mentor at the Academic Collections, Mistress Boileau. When the boy’s parents were executed for plotting against Guarantor Porra, Boileau had sent him to Adele.

That was perfectly reasonable. Adele didn’t understand why, however, after she’d helped Rene get his feet under him on Cinnabar, he’d continued to follow her in the RCN instead of finding a civilian occupation. Adele’s contacts could have opened almost any door for him.

Cory was even more puzzling. He’d been a barely marginal midshipman when he was assigned to the Princess Cecile. Some of his classmates had blossomed under Daniel’s training, but Cory had remained a thumb-fingered embarrassment … until Adele had more or less by accident found that the boy had a talent for communications—and used him. To the amazement of herself and Daniel both, Cory had managed to become a more-than-passable astrogator as well.

Well and good; Adele was of course pleased. But Cory apparently credited her with his turnaround, whereas Adele would be the first to say that she would be better able to fly by flapping her arms than she would be to astrogate. She didn’t even know how to direct the astrogation computer to find a solution the way many of the senior enlisted personnel could.

Tovera led the way out of the transport, her hand within the half-open attaché case she carried in all circumstances which didn’t allow her to show weapons openly. There was almost no chance of someone trying to attack Adele here at Bantry, but Tovera would say that no one had ever been murdered because their bodyguard was too careful. Tovera wasn’t going to change her behavior, so it was a matter on which mistress and servant would simply disagree.

The assorted spacers were already mixing with the crowd of Bantry tenants. Both groups were in their party clothes, but they were as distinct as birds from lizards. The Sissies wore ribbons and patches, while the Bantries were in solid bright colors—generally in combinations that clashed. Muted good taste wasn’t seen as a virtue either by spacers or farmers, it appeared.

Adele smiled. “Mistress?” said Tovera, who flicked quick glances behind her as well. Presumably she was concerned that the transport’s driver might enter to creep from the cockpit to shoot Lady Mundy in the back.

“I was wondering … ,” Adele said, “how my tailor would react if I asked him to run me up a liberty suit.”

“Any of the Sissies would be proud to do the work, Mistress,” Tovera said with a straight face and no inflection. “They’d fight each other for the honor.”

She paused, then added, “Woetjans would win.”

“Yes,” Adele agreed dryly. “Woetjans would win.”

A sociopath shouldn’t be able to joke, but Tovera had certainly learned to counterfeit the act. At least the comment was probably meant as a joke.

The Princess Cecile’s bosun was six-foot-six and rangy rather than heavy. She—Woetjans was biologically female—had always struck Adele as abnormally strong even for her size, and the length of high-pressure tubing she swung in a melee was more effective than a sawed-off shotgun.

Miranda Dorst had just reached the bottom of the ramp. She waited in the middle of a group of children, smiling up at Adele.

Daniel had kept company with many women in the years Adele had known him. Most of them had been prettier than Miranda—a healthy girl, but not a raging beauty; and none of them had displayed half Miranda’s intelligence.

Adele respected Miranda, which permitted her to like the younger woman as well. She hoped that matters went well for her and Daniel, which didn’t—Adele smiled briefly, coldly—necessarily mean that they would marry. But Miranda was adult, quite smart, and certainly knew her own mind.

Women with floral aprons and contrasting bonnets were descending on Miranda’s gaggle of children like jays on a swarm of termites, whisking them off one at a time by a sleeve or an ear. A boy remained, but a girl of sixteen or so was coming at a run with her eye on him.

“Adele, I’m so glad to see you,” Miranda said, sounding as though she meant it. “Is this your first visit to Bantry? I’m sure it’s a wonderful place when one learns to appreciate it, but I’ll admit that I’ve always been a city girl.”

“Lady Mundy, Lady Mundy!” squealed the boy. He couldn’t have been more than six.

“Robbie!” cried the girl running toward him.

“Are you the Squire’s girlfriend, Lady Mundy?” Robbie demanded. “We all think you are!”

The girl clouted Robbie over the ear. He yelped; she smothered his outrage in folds of her scarlet apron which overlay the blue/green/yellow checks of her skirt.

“Your Ladyship, I’m so sorry!” the girl said. Her cheeks were almost as bright as the fabric. “He’s my brother and it’s my fault, I was supposed to watch him, I’m so sorry! I’m Susie Maynor and I shouldn’t have let it happen!”

“Thank you, Mistress Maynor,” Adele said. Her voice and expression were emotionless, but she had made the intellectual decision to find the business amusing. That was the proper response, especially with a child; though it wasn’t the direction her thoughts had first turned. “You may assure Master Robbie when he reappears that I am not the Squire’s girlfriend.”

“Oh, Your Ladyship!” the girl gasped. She strode toward the main gathering with determination, ignoring the muted wails from her apron.

Adele, grimacing internally, met Miranda’s eyes. As she—and probably both of them—wondered what to say or whether better to ignore the business, Tovera said, “I’ve been in Captain Leary’s company for a number of years now, but no one has made similar assertions about me. If I had human feelings, they would be hurt.”

Miranda blinked at Tovera, then smothered a giggle with her hand. Adele only grinned slightly, but the expression meant more in her case than it would for most people. Aloud she said, “Would you like a raise, Tovera?”

Her servant gave her a wintry smile. “What do I need money for, mistress?” she said. She had closed her attaché case. “You provide my food and lodging, and you point me to plenty of people to kill.”

Which may be a joke, Adele thought. “Yes,” she said, “but not here.”

“Daniel asked me to take you to the house,” Miranda said as she turned. She started back along the arc of the commons instead of the chord of the sea front. She cleared her throat, perhaps still embarrassed. She said, “He isn’t really the Squire, you know. His father is, and Deirdre will inherit if, well … when …”

Her voice trailed off.

“I don’t believe Speaker Leary is immortal, either,” Adele said, letting the words rather than her dry tone supply the humor. “But ‘Squire’ is a term of custom rather than law. If the Bantries choose to grant the title to Daniel who grew up with them rather than to his father to whom the estate is merely a muddy asset, then I applaud their judgment.”

They walked close to the tenant houses. Adele could see that the fronts were decked with swags of foliage and flowers, not bunting as she’d thought from the transport’s hatch. Dogs barked from some of the fenced dooryards.

Miranda followed Adele’s eyes. With quiet pride she said, “They really love him, don’t they?”

“Yes,” said Adele. “Just as the Sissies do. The tenants don’t find their lives at considerably greater risk from associating with Daniel, but even so I don’t think a computer could have predicted the depth of feeling.”

Miranda laughed. She was a cheerful person, a good fit with Daniel in that way. She hadn’t had an easy life, but the troubles didn’t appear to have marked her.

Whereas Adele—she smiled wanly at herself—hadn’t been particularly happy even when she’d been the heir to one of the wealthiest and most powerful houses of the Republic. She’d often been content, though; as she was generally content now, except the nights that she lay in the darkness, surrounded by dead faces that she’d last seen over the sights of the pistol which even now nestled in her left tunic pocket.

The piper was taking a break, and at least a dozen men had begun singing “The Ring That Has No End” without accompaniment. They stumbled up to “ … when you find one who’ll be true,” but by the time they reached, “Change not the old friend for a new,” their voices had blended into a natural richness which Adele found beautiful. Her hand reached for her data unit as it always did when she was really engaged by her surroundings, but she had nothing to look up.

Her lips twitched, though her expression couldn’t have been called a smile: she reached for her data unit, or she reached for her pistol. Either way, she preferred to keep a mechanical interface between herself and the world.

“I’m so glad they’re getting along,” Miranda said, also watching the festival. She and Adele walked side by side. Tovera followed at a respectful distance of two paces. “I was afraid there’d be, well, fights between spacers and tenants.”

“There probably will be,” Adele said. “And fights among spacers and fights among tenants. Most of both groups will be drunk before the night’s out, and those who aren’t falling-down drunk will include some who want to knock other people down. But they all respect Six—or the Squire, depending—too much for it to go beyond fists. And remember, at least a score of the present Sissies were tenants before they enlisted.”

And anyone who wasn’t sufficiently respectful to begin with would have a proper understanding beaten into him by Woetjans or Hogg, each policing the group they came from. They would certainly be drunk also, but Adele couldn’t imagine them too drunk to do their duty.

She took that sort of implicit violence for granted now. Her father, knowing that a leading politician was open to many pressures, had seen to it that not only he but his wife and daughters were known to be crack shots who would certainly kill anyone who challenged them to a duel. That hadn’t helped him the night troops arrived with the notice of the Proscriptions, but it had kept Adele alive during her years of slums and squalor.

This was different, though: this was force applied in the service of order, not chaos. Her mother, who had believed in the innate decency of the Common Man, would have been horrified; her father would have been disgusted.

Adele, who had lived in very close quarters with the Common Man ever since the Proscriptions, took the same sort of detached view that she had of lice: there were discomforts which you alleviated if you could and bore if you couldn’t. There were no moral questions involved, just practical responses.

And a crack on the head with plenty of muscle behind it was often a very practical response.

The double leaves of the manor’s front door were standing open onto the veranda; guns and fishing tackle hung from hooks in the hallway behind. The gear looked well cared for, though there wouldn’t have been anyone living in the building since Daniel had left Bantry to join the RCN.

Tovera skipped ahead; her right hand was within the attaché case again. The hall and the rooms to either side along the central passageway were empty.

If Miranda was surprised by Tovera’s behavior, she didn’t comment on the fact. Instead she said, “I’ll take you through to the library, Adele, and then go back to the party.”

She smiled fondly. “I need to give my mother a bit of a break, I’m afraid,” she said. “When the Bantry women learned we’d both made our own dresses—”

She touched her skirt. The fabric was sturdy, but the pattern of magenta flames on the white background made it stand out even in these festivities. The lines, though loose enough to be comfortable, flattered what was already quite a good figure.

“—nothing would help but we had to show them every seam.”

Miranda knocked on the last door to the right, where the passage jogged into the new wing. “Enter,” called a voice that had become familiar to Adele over the years.

Tovera reached for the latch; Adele stepped past and said, “No.”

She opened the door and entered what passed for a library here.

“Did you have a good trip, Mundy?” asked Bernis Sand, seated at the reading table with a bottle of whiskey, a carafe of water, and two glasses before her.

“No worse than I expected,” Adele said to the Republic’s spymaster. When the door closed behind her, she went on, “What did you wish to speak to me about, mistress?”

CHAPTER 2

THE BANTRY ESTATE, CINNABAR

“You’re not one for small talk, are you, Mundy?” said Bernis Sand. She tapped the bottle. “Help yourself to the whiskey.”

“No,” said Adele, “I’m not. And I expect the sun to rise in the east tomorrow, if you choose to discuss the obvious.”

Adele had known she was in a bad humor, but she hadn’t been aware of exactly how bad it was until she heard herself. Despite that, she took the bottle and poured a half-thimbleful into the glass. After swirling the liquor around, she filled the glass from the carafe.

It was what she’d done in the years when the water where she lived wasn’t safe to drink. The liquor wasn’t safe either, of course, but in small doses it would kill bacteria without being immediately dangerous to a human being.

It wasn’t precisely an insult to treat Mistress Sand’s whiskey that way. But it wasn’t precisely not an insult, either.

Adele took a sip. Very calmly, Sand said, “What’s wrong, Mundy? The last mission?”

Adele set the glass down. She swallowed, trying to rid herself of the sourness which—she smiled—was in her mind, not her mouth.

“I’m sorry, mistress,” she said. “I—”

She paused, wondering how to phrase it without being further insulting. The things other people said or did would always give room to take offense, if you were of a mind to take offense. Therefore the fault wasn’t in the other people.

“Yes, I suppose it was the most recent mission, the battle above Cacique at least,” Adele said. “It affected me more than I would have expected.”

“Your ship was badly hit,” said Sand as Adele paused to drink. “I understand that it will probably be scrapped instead of being rebuilt. You could easily have been killed.”

Adele smiled faintly and refilled the glass with water. Her mouth was terribly dry. When she laughed, the ribs on her lower right side still ached from where a bullet had hit her years ago on Dunbar’s World. Fortunately, she didn’t laugh very often.

“I’m not afraid of being killed, mistress,” Adele said, meeting the spymaster’s eyes over the rim of her glass. “I haven’t changed that much.”

“Go on, then,” Sand said quietly. She was a stocky woman on the wrong side of middle age. In the brown tweed suit she wore at present, she could easily have passed for one of the country squires Adele had seen with Daniel on the sea front.

Mistress Sand had been more important to the survival of Cinnabar in its struggle with the much larger Alliance than any cabinet minister or admiral in the RCN. What Adele saw in the older woman’s eyes now were intelligence and strength … and fatigue as boundless as the Matrix through which starships sailed.

“Debris flew around inside the ship after the missile hit us,” Adele said. “A piece of it struck Daniel—that is, Captain Leary—”

Sand flicked her hands in dismissal of the thought. “Daniel,” she said. “This isn’t a formal report. It’s two old acquaintances talking. Two friends, I’d like to think.”

“Yes,” said Adele. “Debris struck Daniel in the head.”

She raised the carafe, but her hand was trembling so she quickly put it back. Sand reached past and filled the glass.

“It cracked his helmet and gave him a concussion, but the injuries weren’t life threatening,” Adele said. “If it had struck an inch lower, however, it would have broken his neck. Severed it, like enough. That would have been beyond the Medicomp or any human efforts to repair. And I don’t believe in gods.”

“An RCN officer’s duties are often dangerous,” Sand said, carefully neutral. Adele realized that the spymaster still didn’t understand the problem. Sand was afraid of saying the wrong thing—and equally afraid of seeming uninterested if she didn’t say anything. “That might have happened to any of you.”

“Yes,” said Adele, “exactly. Whereas I’d been thinking—feeling, I suppose—that it might happen to all of us. That is, if a missile hit our ship, we would all be killed. That event, that incident, proved that there might well be a future in which Daniel was dead and I was alive.”

She took her glass in both hands and drained it again. This wasn’t coming out well, but she wasn’t sure there was a better way to put it.

“Mistress,” Adele said, “I’ve built a comfortable life. Rebuilt one, perhaps. The RCN is a family which accepts and even appreciates me. The Sissies, the spacers whom I’ve served with, they’re closer than I would ever have been with my sister Agatha in another life.”

In a life in which two soldiers hadn’t cut off Agatha’s ten-year-old head with their belt knives and turned it in for the reward.

“And Daniel himself … ,” Adele said. She didn’t know how to go on. She hadn’t expected this conversation. She hadn’t expected ever to have this conversation. It was obvious that she was in worse shape than she had imagined only a few moments ago.

It was less obvious to see how she was going to get out of her present straits.

Adele felt her lips rise in an unexpected smile. The RCN prided itself that its personnel could learn through on-the-job training. No doubt life would prove amenable to the same techniques by which Adele had learned to be an efficient signals officer.

“There’s no one like Daniel,” Adele said simply. “I don’t mean ‘no one better than Daniel,’ though in some ways that’s probably true. But my entire present life is built around the existence of Daniel Leary. I would rather die than start over from where I was when I was sixteen and lost my first family.”

Mistress Sand sighed. “I have my work, Mundy,” she said. “And my—”

Her face went coldly blank, then broke into an embarrassed grin. “I may as well be honest,” Sand said. “I have my children. That’s how I think of them.”

With a hint of challenge she said, “That’s how I think of you.”

“I wasn’t a notably filial child when I was sixteen,” Adele said. “Perhaps I’ll do better with the advantage of age.”

Sand laughed and pushed the bottle another finger’s breadth across the table. From her waistcoat she took a mother-of-pearl snuffbox. She sifted some of the contents from it into the seam of her left thumb closed against her fingers.

Adele poured two ounces of whiskey and sipped it neat. It was a short drink but a real one, and an apology for her previous behavior.

“You were wondering why I wanted to see you,” Sand said. Her eyes were on her snuffbox as she snapped it closed. “Are you ready to go off-planet again, do you think?”

“Yes,” said Adele. She’d considered the question from the moment she’d been summoned to this meeting, so she spoke without the embroidery others might have put around the answer.

Sand pinched her right nostril shut and snorted, then switched nostrils and repeated the process. She dusted the last crumbs of snuff from her hands, then sneezed violently into her handkerchief. She looked up with a smile.

“There’s a Senatorial election due in four months, perhaps even sooner if the Speaker fancies his chances,” she said. “All the parties will attempt to use Captain Leary. He’s a genuine war hero and, shall we say, impetuous enough that he might be maneuvered into blurting something useful.”

“Yes,” Adele repeated, waiting.

“That would be a matter of academic import to me,” Sand continued, “were it not for the fact that Leary’s close friend is one of my most valued assets, and that asset would become involved also.”

Sand cleared her throat. “Do you suppose Captain Leary would be willing to undertake a charter in his private yacht to deliver the new Cinnabar Commissioner to Zenobia?”

Adele set her data unit on the table and brought it live. Sand knew her too well to take the action as an insult, but that wouldn’t have mattered: Adele had done it with no more volition than she breathed. If asked whether she would prefer to be without breath or without information, she would have said there was little to choose from.

“I had understood … ,” she said as her fingers made the control wands dance. She found the wands quicker than other input devices—and so they were, for her. Adele used them as she did her pistol, at the capacity of the machine. “… that Daniel was to be kept on full pay despite the fact that the Milton is scheduled to be broken up.”

“That’s correct,” Sand said, pouring herself another tumbler of whiskey. She controlled her reactions very well, but Adele could tell that the older woman was more relaxed than she had been since Adele entered the room. “The officers and crew will serve as members of the RCN—”

Sand used the insider’s term instead of referring to “the Navy.”

“—but as a matter of courtesy to the Alliance, they will be in civilian dress while in Zenobian territory, and their ship will be a civilian charter rather than a warship.”

Adele smiled slightly as she flicked through the holographic images which her data unit displayed. Common spacers generally wore loose-fitting garments, whether their ship was a merchant vessel or a warship—of the RCN, the Alliance Fleet, or one of the galaxy’s smaller navies. The colors were all drab, but the particular hue depended on where the fabric had been dyed rather than who was wearing it. If they were worn by Power Room crew, lubricant and finely divided metal had turned them a dirty black.

Officers wore RCN utilities on shipboard duty. For most of the crew, utilities were dress uniform—and formed the base for liberty suits.

“A voyage to Zenobia will certainly keep the brave Captain Leary out of the political arena for a suitable period of time,” Adele said dryly as she skimmed information on Zenobia. There were specialist databases—virtually every database on Cinnabar was open to a combination of Adele’s skill and the software which Mistress Sand had supplied—but it scarcely seemed necessary here. Unless the readily available material—which included the Sailing Directions for the Qaboosh Region, published by Navy House—was wildly wrong, Zenobia had no depth to go into.

“Yes,” said Sand. “It fits that criterion amply, since it’s a sixty-day run for merchant vessels.”

She smiled wryly and added, “I have no doubt that you’ll tell me that Captain Leary can better that estimate, Mundy. Nonetheless, the distance justifies our hero being absent for as long as the campaign season requires.”

“Any RCN vessel could better the estimate, I suspect, mistress,” Adele said, hearing a touch of asperity in her tone. She smiled, amused to realize that she had become just as protective of the honor of the RCN as she was that of the Mundys of Chatsworth. “It’s as much a factor of the larger crews of a naval vessel as it is of the much higher level of astrogation training to be expected of the officers.”

“I bow to your greater experience in the matter, Mundy,” said Sand. Adele wondered if the older woman would have been less amenable to the pedantry if she weren’t so relieved to be past the awkward scene with which the interview had opened.

Clearing her throat, Sand continued, “Zenobia is typical of the Qaboosh Region, meaning it’s of no particular account. Both we and the Alliance have tributaries and a naval base there, but the region is such a backwater that both parties chose to ignore it during the recent hostilities. Sending a real fighting squadron to the Qaboosh would have wasted strength which was needed closer to home.”

“Is Zenobia an Alliance possession?” Adele said, scrolling rapidly through data without finding the answer she wanted. “It appears to be one, but there shouldn’t be a Cinnabar Commissioner if it were.”

“Zenobia is technically independent, with a Council and an executive—the Founder—elected for life by that Council,” Sand said. “Foreign policy and realistically everything more important than the level of the food subsidy for Calvary, the only real city, is in the hands of an Alliance Resident. I suspect that if the Resident cared about the food subsidy, he could change that also.”

Adele nodded, her eyes on her own data streams. Now that she knew what she was looking for, she found considerable detail.

“You’re probably wondering why we even have a Commissioner on Zenobia,” Sand said. She tapped the bottle forward again, but Adele was absorbed in her information gathering.

“Not at all,” Adele said, more curtly than she would have done if her intellect hadn’t been focused in other directions. “A good quarter of the region’s spacers appear to be from Rougmont, one of our client worlds. I suspect very few of them are actually Cinnabar citizens, but based on what I’ve noticed on the fringes of civilization, most will claim to be Cinnabar citizens when they’re jailed for being drunk and disorderly. Their normal state when they’ve been paid upon landfall.”

A Resident was a senior official in the Cinnabar’s Ministry of External Affairs. He or she directed the local leaders of worlds which were Friends of Cinnabar: that is, tribute-paying members of the Cinnabar Empire.

Not that anybody put it that way. Those who did were promptly imprisoned for Insulting the Republic.

“Ah,” Adele said with more satisfaction than most people would have packed into that simple syllable. “I was wondering why I wasn’t finding more evidence of piracy. Our ally, the Principality of Palmyra, patrols the region and appears to do a very good job of it.”

Her lip quirked in a wry smile. She said, “It would seem that they do a better job than dedicated anti-pirate squadrons in other regions, whether mounted by us or by the Alliance.”

“Just for my curiosity, Mundy … ,” Mistress Sand said. Despite her attempt to seem casual, her eyes had narrowed slightly. “How do you determine the effectiveness of the patrols? Do you have Admiralty Court records in your computer?”

Adele laughed. “I could get them from the database in Navy House,” she said. “Or for that matter from the duplicate set that the Ministry of Justice is supposed to keep. I doubt if they’d tell me much, though. Our own patrols are rumored to take shortcuts when dealing with pirates, and the Palmyrenes certainly do.”

She met Sand’s eyes for the first time since she’d brought up her data unit. “It’s much simpler,” she said with a cold grin, “to check insurance rates for the region. They’re as low as those for the Cinnabar-Blanchefleur route.”

Sand laughed ruefully. “Rather than say, ‘Oh, that’s simple,’ I’ll note that the mind which went directly to that source wasn’t simple at all,” she said. “And yes, Palmyra has nominally been a Cinnabar ally for several generations, though that’s basically been a matter of the Autocrators choosing a policy which is in keeping with the aims of the Republic. Palmyra has become a major trading power—the trading power in its region, certainly—and has put down piracy for its own ends.”