Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

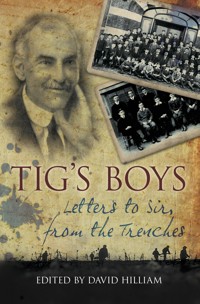

The Lost Generation of the First World War were boys who had barely left school before they found themselves living in trenches, drowning in mud and living in constant fear of death. This unique collection of letters from a group of schoolboys who attended Bournemouth Grammar pays tribute to these boys who barely had the chance to become men. Bournemouth's grammar school was founded in 1901. Tragically, all boys who were pupils there in its first decade grew up to be of fighting age in the bloodiest war in history. Ninety-eight of them were killed, averaging about one death every fortnight throughout that conflict. However, it was not all unrelieved blood and slaughter. Life was hard, but often full of interest and surprise. Many of them wrote back to 'Tig' – their much-respected headmaster to tell him of their wartime adventures. Collectively, these letters provide a wide spectrum of the 'Great War.' We read of young men enjoying trying to catch rats in the trenches, winning bets on how long it would take to rescue a tank from no man's land, playing 'footer' amid the gunfire, and singing 'ragtime' in a rickety new-fangled aeroplane while 'rocking the machine in time to it.' This is the voice of the Lost Generation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 245

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TIG’S BOYS

Other books by David Hilliam published by The History Press

Kings, Queens, Bones and Bastards

Monarchs, Murders & Mistresses

Crown, Orb & Sceptre

A Salisbury Miscellany

Winchester Curiosities

Why Do Shepherds Need a Bush?

The Little Book of Dorset

TIG’S BOYS

Letters to Sir, from the Trenches

EDITED BY DAVID HILLIAM

First published 2011 by Spellmount,

an imprint of The History Press

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© David Hilliam, 2011, 2013

The right of David Hilliam to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5409 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

A Brief Timeline

Prologue

Tig and His School

One

Life in the Trenches

Two

In those Flying Machines

Three

Around the World

Four

Getting Wounded

Five

Tig tells of Ninety-Eight Deaths

Appendix 1

Dates, Facts and Figures

Appendix 2

Decorations Gained

Epilogue – 1919

Epilogue – Twenty-First Century

Further Reading

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks are warmly given to the present headmaster of Bournemouth School, Dr Dorian Lewis, for allowing me access to the school archives. I am also greatly indebted to a former pupil of the school, Roger Coleman, MBE, whose own meticulous research into the War Memorials of Bournemouth School enabled me to add information concerning the burial places of every one of Tig’s Boys – or in many cases to add information about the exact places where their names are recorded.

The pictures of Dr Fenwick, the school itself and the various groups of academically gifted boys are taken from the school’s centenary publication, Bournemouth School 1901–2000. I am most grateful to Stuart Wheeler, Assistant Librarian of Bovington Tank Museum, for his help in providing me with the picture of the ‘Little Willie’ tank (probably the only example of its kind to survive). Equally, I am indebted to Pauline Allwright and Tom Eaton of the Imperial War Museum for their help in finding images for me from their vast picture archive. I am particularly grateful to Mark Warby, in helping me to secure permission from Barbara Bruce Littlejohn (daughter of Bruce Bairnsfather) to use three of Bruce Bairnsfather’s famous cartoons.

And finally, my loving thanks go to Jim and Denise Watt for their kindness in sending me the image of the Military Cross, won in Mesopotamia by Denise’s grandfather, and which they now hold in safe keeping in Brisbane, Australia.

INTRODUCTION

Bournemouth’s grammar school for boys was founded in January 1901. No one knew it at the time, but those boys who became pupils there during its first decade were destined to be of fighting age in the world war of 1914–18, arguably the bloodiest war in history.

The War Memorial in the school’s entrance hall lists the names of ninety-eight of those young men who were killed in that war. Tragically, this averages about one death every fortnight over the full length of that terrible time.

However, it was not all unrelieved blood and slaughter. Life was hard, but often full of interest and surprise. Those old boys of Bournemouth School constantly wrote back to ‘Tig’ – their much-respected headmaster – to tell him of their wartime adventures.

Collectively, these letters provide a wide spectrum of the ‘Great War.’ We read of young men enjoying trying to catch rats in the trenches, winning bets on how long it could take to rescue a tank from no man’s land, playing ‘footer’ amid the gunfire, and singing ‘ragtime’ in a rickety new-fangled aeroplane while ‘rocking the machine in time to it’.

This book is a mosaic of such wartime experiences.

It has been compiled not only to honour the memory of those who lost their lives, but also to show present generations how one typical group of ex-schoolboys coped with circumstances over which they had no control.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not wither them, nor the years condemn.

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

Mostly, this book is a collection of extracts from the magazine of Bournemouth School, taken either from the letters sent to the headmaster, Dr Fenwick, from ex-pupils who were serving at the Western Front or elsewhere in the world, or else items written by Dr Fenwick himself, such as the obituaries of those who were killed.

The wording of the text is exactly as published in that school magazine. The only editorial changes made are in breaking up some of the very lengthy paragraphs into shorter units, and omitting some personal and extraneous material.

Occasionally, a very long letter has been broken up, so that it appears as two, or even three separate items.

After nearly a century, it has not been thought feasible to contact possible descendants or relations. It is hoped, however, that any descendants who read this book will not be offended, and that they will take pride, as does the school, in the heroism of all those who took part in that terrible ‘Great War’.

The First World War, 1914–1918

A BRIEF TIMELINE

1914

4 August

Britain declares war on Germany

23 August

Battle of Mons

6–10 September

Battle of the Marne

19 October–22 November

First Battle of Ypres

1915

10–13 March

Battle of Neuve Chapelle

22 April–25 May

Second Battle of Ypres

22 April

First use of gas on the Western Front

25 April–20 December

Gallipoli expedition

7 May

Sinking of the Lusitania

31 May

First Zeppelin raid on London

9 October

British and French troops land at Salonika, Greece

13 October

Battle of Loos

13 December

British and French troops occupy Salonika

1916

8 January

Gallipoli evacuation completed

21 February–16 December

Battle of Verdun

29 April

British troops surrender at Kut

31 May–1 June

Battle of Jutland

1 July–18 November

First Battle of the Somme

15 July–3 September

Battle of Delville Wood

3 September–23 September

Battle of Pozières

10 September–19 November

Allied offensive at Salonika

15 September

First use of tanks on Western Front

1917

9–14 April

Battle of Arras

9–14 April

Battle of Vimy Ridge

7–14 June

Battle of Messines

31 July–10 November

Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele)

6 November

British capture Passchendaele Ridge

20 November–3 December

Battle of Cambrai (the first battle where a large number of tanks are used – 378)

9 December

British capture Jerusalem from the Turks

1918

21 March–4 April

Second Battle of the Somme

9–29 April

Battle of the Lys

20–31 July

Battle of the Marne

5–18 August

Start of the ‘Hundred Days’ with the advance in Flanders

8 August

British attack at Amiens (Ludendorff described this as ‘the Black Day’ for the German army)

24 August–3 September

Third Battle of the Somme

18 September–9 October

Battle of the Hindenburg Line

17 October

Occupation of Lille

11 November

Armistice with Germany

Prologue

TIG AND HIS SCHOOL

Schoolboys have always taken a mischievous delight in finding odd nicknames for their teachers, springing not only from their ingrained impudence, but also – and very frequently – from a special kind of loving respect.

‘Tig’ was the nickname of Dr Edward Fenwick, first headmaster of Bournemouth’s grammar school for boys, from its foundation in 1901 until his retirement in 1932. It was, in fact, short for ‘Tiger’ – and presumably it reflected Fenwick’s unbounded energy and ferocious discipline.

Sadly no one is alive now to give a personal account of this remarkable schoolmaster, but his supreme knack of commanding loyalty and getting the best out of his boys is evident throughout the pages of the school magazine, which he wrote and edited during his long headmastership.

Bournemouth itself had grown up within a generation. Only fifty years before, in 1851, the population had been just 695, but the following decades had seen such swift development that the population had grown to 16,859 by 1881 and to 60,000 by 1901. Thomas Hardy described the land on which Bournemouth was developing in his Tess of the d’Urbervilles, published in 1891 – a mere ten years before – remarking that ‘not a sod had been turned there since the days of the Caesars’.

By 1901 it was patently obvious that this new town should be provided with good schools. A grammar school was an urgent necessity and accordingly a ‘Dr Edward Fenwick, MA, LLD, BSc, Cambridge 10th Senior Optime in Mathematical Tripos, 1890, (late of Wellingborough Grammar School)’ had the good fortune to become its first headmaster. He was to be given a salary of no less than £100 a year plus a capitation fee of £3 per pupil.

THE FIRST DAY

At nine o’clock on Tuesday, 22 January 1901, fifty-four boys assembled in the hall of their brand new school. They must have cringed under the eagle eyes of their fierce, newly-appointed headmaster, Dr Edward Fenwick, and his two full-time and two part-time members of staff.

For just that one day in the life of the school, Queen Victoria was still the reigning monarch. For sixty-three years she had ruled her worldwide empire, latterly from Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, 25 miles away. But this was to be the last day of her reign, and shortly after those fifty-four boys arrived home that afternoon, she died.

Thus it was that when the pupils arrived in school the next morning, the Edwardian Age had begun; a new king, a new school, and a new, exciting century, full of hope and promise. The future beckoned.

THE PRE-1914 YEARS

Tig must have been in his early thirties when he took up his headmastership, and how he relished it.

For most boys it was a day school, serving the Bournemouth area, but Fenwick and his young wife, helped by a ‘duly qualified lady matron’, looked after a handful of boarders, so for some of his pupils, Tig was very much a father figure. Shortly after taking up his appointment, his wife had twin boys, so the family atmosphere in this small school community must have been apparent.

From fifty-four boys, the school grew rapidly, together with more staff and of course all the familiar activities associated with a busy group of teenagers: football, cricket, OTC (Officers’ Training Corps), theatricals, Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and so on. When an appeal was made for money towards the expenses of Captain Scott’s forthcoming expedition to the South Pole, enough money was eagerly subscribed to purchase a sleigh dog.

The school magazine reported that:

We were kindly allowed to say what name the redoubtable animal should bear on its historic journey. The result was that our representative is to rejoice in the name of ‘Tiger’… May he be of a milder nature than his name indicates, and we hope he will return safely after the expedition has successfully attained its object.

Captain Scott himself sent thanks to the boys, though he could hardly have been aware, as the boys were, that Tiger’s name had a semi-secret special significance!

The outstanding feature of the school, however, as Tig drove it forward, was its excellent academic results. They were truly phenomenal. Right from the start, Dr Fenwick entered boys for the Cambridge Local Examinations, the equivalent of today’s GCSEs and A Levels. In those days there were far fewer candidates, nationally, and although it may seem astonishing to think of it now, Cambridge actually published an order of merit of candidates in each subject.

A memorable photo taken in those years before the First World War shows Tig and three of his pupils: one had been placed first of all 2,419 candidates in the Cambridge Senior Examinations in 1912; another had been placed first out of 2,777 candidates in 1913 and again first out of 2,846 in 1914; and the third had come first out of 3,196 candidates.

These results were no fluke. Boy after boy gained near firsts. In 1917, Fenwick proudly listed nine areas of academic distinction in which the school stood first in England. Another early photo shows fourteen youngsters who had gained various honours in a wide range of subjects. For many years the school achieved the best results of any on the South Coast, and was second best of all the 300 schools entered for the examination – ironically, second only to Wellingborough, Fenwick’s previous school.

This, then, was the generation of boys who were called upon to fight in the Great War. Broadly speaking, all pupils who entered Bournemouth School in the first ten years of its existence were eligible to fight. Tragically, they were destined to be subjected to the unimaginable and unprecedented demands made of them by the politicians of their day and the hapless generals.

THE COMING OF WAR

Dr Fenwick’s reaction to the situation: a contemporary view

The school magazine of July 1914 has a poignant innocence. It was wholly concerned with school affairs, with no national events casting their shadows. However, it was to be the last of its kind. War was declared the following month, on 4 August, and nothing was to be the same again.

The declaration had come when all the boys were on holiday, so when they reassembled for the Autumn Term, every one of them must have been keenly aware of the dramatic events beginning to take place in France and elsewhere in the world. The autumn magazine of December 1914 spells it out, and Dr Fenwick wrote a solemn account of the situation. Already one master and two old boys had been killed.

The following article by Dr Fenwick in that December magazine is given below – only very slightly abridged. It is quoted at length because it gives a clear indication of the mood of the times. Now, a century later, it can be read as history.

‘…A glow of legitimate pride…’

With startling suddenness the greatest war of all time has broken in upon the peace of the world, and at our very doors rages the conflict on the issues of which depend not only the Empire’s safety but the very existence, perhaps, of our country as a separate nation.

A careful survey of the official documents issued by the Allies and relating to the events which led up to the war, leads to the conviction that, with the Germans and with them alone, rests the blame for this appalling catastrophe.

Confident in the power of the mighty war-machine which in the last thirty years they had created, they seemed to have resolved to stake all on a war against the powers standing between them and the world domination at which the Prussian military party aimed. True to their reputation, the Balkan States provided the spark which kindled the conflagration, for it was a quarrel between Austria and Servia [sic] that brought about the rupture between Russia and Germany, when France, too, as the ally of Russia, became a party to the war. Though England managed to stand aloof for a short time longer, she was ultimately compelled to take up arms against Germany, when the latter, by invading Belgium, deliberately and for her own ends, broke the treaty guaranteeing the integrity of that country. Alongside the recognition that this war is being waged not against the Germans as a people, grows thee firm conviction that there can be no end to the conflict until the Prussian military despotism has been so completely crushed as to be incapable of further inroads on the world’s peace.

To this end it behoves every Briton worthy of the name to be up and doing his utmost, whether it be in the active service of the battlefield or in the more prosaic discharge of the duties which each day brings.

To the call for men our Colonies have responded nobly. The United Kingdom has already enrolled more than a million volunteers, and will find as many more as may be needed. We may well feel proud in these days of stress to be the countrymen of our soldiers now earning for themselves undying fame in France and Belgium, and we may, too, feel a glow of legitimate pride that we are members of a School whose Old Boys have needed no pressing to flock to the colours.

When we consider that the School was opened less than 14 years ago, that not more than twenty of our Old Boys have reached the age of 27, and that the average age is about 21, we can point with much satisfaction to the fact that we know of no fewer than 170 who have come forward to help their country in its time of need by joining some unit of HM Forces.

We are proud of every Old Boy who [has enlisted] and to all we offer our heartiest congratulations and good wishes.

The school magazine, December 1914

In December 1914, no one could have foreseen the terrible carnage that was about to ensue, lasting for more than four years. However, to the very end of the war Dr Fenwick continued to be proud of his boys, encouraging them to enlist and honouring those who were killed in his obituaries of them in successive editions of the school magazine.

It must have been a continual agony of grief as he received message after message telling him of the deaths of his former pupils and staff. In fact, the final number of those killed from Bournemouth School was ninety-eight. It averaged one death every sixteen days – or about two per month throughout the full course of the war.

THE SCHOOL DOES ITS BIT TO HELP WIN THE WAR

While those hundreds of Old Boys were serving in the trenches and on the sea, with a few of them in the air, the boys still at school, encouraged by Tig, were also doing their bit to help win the war.

It was still a horse-drawn, gas-lit world in 1914. A world in which men and boys wore thick, itchy clothes and women wore their skirts and dresses down to the ground. Girls were expected to stay at home with their mothers after leaving their elementary schools, and career opportunities for them were almost non-existent. Bournemouth had not yet thought it worthwhile to provide a grammar school for girls.

Cars were just beginning to trundle over roads not yet ready for them. Cinemas, radios and gramophones were all in their early experimental stages. It was certainly a world without television, videos, mobile phones, computers, central heating or convenience foods. It is probably true to say that none of Tig’s boys had ever been abroad.

However, patriotism was paramount, and belts had to be tightened. Sacrifices, however small, were important. Accordingly, ‘an appeal was made to the boys to make weekly contributions from their own pocket money to supply our fighting forces with comforts in the way of clothing. The response was most satisfactory, and we were able to send a very useful parcel each week.’

It was recorded that the total sum collected during the first term was twelve pounds, one shilling and ninepence. This may seem a trivial amount today, but it was possibly about the equivalent of Tig’s monthly salary.

Woollen garments were also collected, and so were old waste newspapers, the sale of which in the summer of 1916 brought in eleven pounds, four shillings and eight pence for the National War Relief Fund. For this effort, the private secretary to the Prince of Wales – known to later generations as King Edward VIII and subsequently as the Duke of Windsor – wrote a letter to Dr Fenwick to congratulate them on their ‘splendid work’:

… by reducing the quantity of paper and paper-making materials imported from abroad… they have helped to retain money in the country and have set free shipping which is badly needed for carrying munitions of war and food. By preventing waste they are helping to provide the sinews of war and so are helping to end the war.

So wrote His Royal Highness, hoping that the boys would continue to collect paper ‘with no less enthusiasm in the coming year’.

Perhaps a more immediately practical task undertaken by the boys was their response to an appeal made in March 1916 by the Matron of the local hospital at Boscombe, to supply wooden bedside lockers for the use of wounded soldiers who were in her charge. A quick collection swiftly produced three pounds two shillings, and this went to buy the required timber. By the summer, the boys had produced thirty-four bedside lockers – gratefully accepted by the hospital authorities.

A sacrifice made on his pupils’ behalf was Dr Fenwick’s decision to abandon the giving of school prizes throughout the duration of the war. The money which would have been spent on these was donated to the war effort, and school successes were rewarded by certificates instead. A considerable amount was raised by this means.

It wasn’t all doom and gloom however, for Tig’s sense of pride and occasion led to his giving the school a half-day holiday whenever an Old Boy was awarded the Military Cross. Whether this always happened is impossible to say, for there were eighteen such awards, but it must have been a morale booster for the boys, and made them appreciate the courage and honour of their elder brothers and cousins.

At home, the boys would have felt the effects of the war increasingly as food and coal became scarce. Also, Bournemouth was designated as a garrison town for 10,000 troops, and by November 1915 16,000 servicemen were billeted, two or three to a house, in nearly every part of the town. It is most probable that many boys would have had soldiers living temporarily at home with them.

A sad moment came when Lord Kitchener drowned on 5 June 1916, with the sinking of HMS Hampshire. It was a moment of national grief and two Old Boys of Bournemouth School also perished in that disaster – Norman Barrow, aged twenty-two, and Ralph Butler, aged twenty (see pages 114 and 118). The Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra played a memorial concert on Bournemouth Pier to an audience of 5,000. Some members of the school must have been in that audience, and their thoughts would inevitably have been with those former fellow pupils, as well as with Lord Kitchener.

The initial outpouring of enthusiasm for the war slowed down as people realised the enormity of it all. ‘Home by Christmas!’ was the phrase used by those who joined up in 1914 – but by the fourth Christmas there was a dogged determination that however long it might take, the fight must go on.

Dr Fenwick regularly listed the names of all those who were serving – a list which he designated as his ‘Roll of Honour’. At Christmas, 1917 – what was mercifully to be the last Christmas of the war – he sent a message to all the hundreds of Old Boys on his Roll of Honour. It captures the spirit of that dark hour:

In spite of all our hopes the war has extended into a fourth year, and a fourth Christmas finds you still in arms against oppression. At this season, we, your friends at the School (Dr. Fenwick, the Master and Boys) would like to be in your thoughts, as you are in ours, and we send you this card with the assurance of our deep interest in, and close sympathy with you in the time of stress that you are facing with so much courage. We hope that our message may remind you of the happy days you spent here, and that their memory may help you to ‘carry on,’ patiently and without complaint, until the achievement of that honourable peace for which you are so nobly striving.

Xmas, 1917

Dr Fenwick added, in the school magazine of the following March, that ‘if one may judge by the number and nature of the replies received, our wishes were very widely and warmly appreciated.’

The following chapters turn to the recipients of that sombre Christmas message. Arguably, their combined experiences provide a microcosm of the conflict that was to be called, without exaggeration, the Great War.

One

LIFE IN THE TRENCHES

War means fighting. However, it also means long periods of discomfort, boredom, dirt, hunger and exhaustion. Those who endured life in the trenches on the Western Front probably remembered the squalor even more than the terror. Nevertheless, these conditions produced camaraderie among those forced to spend weeks and months together.

Arthur Wolfe describes ‘our baptism of fire’

You may be interested in reading a short account of how we underwent our baptism of fire.

It was on or about the 20th of last month [January 1915] that we first went into action. The day before we went into billets only a few hundred yards behind our own lines. On the way up a German maxim caught us, but fortunately only two men were wounded. This happened about ten or fifteen yards behind me.

We were in action altogether that time for four days. The trenches when we went in were muddy but not at all bad, but during the time we occupied them we had rain, snow, hail, or sleet all the time, so that it was not very comfortable or pleasant. During the night a pretty heavy fire was maintained, but at day very little was necessary.

We marched to a village about three miles away and after a rub down, a good strong dose of rum, plenty of food and twelve hours’ sleep we felt very much better. We have been in action since and feel quite old soldiers now.

At present we are resting, but expect to return to the trenches in about a week’s time.

The school magazine, March 1915

Arthur Wolfe describes trench life, ‘…we fare pretty well’

Our losses to date number four or five killed, and about twenty-four wounded.

I believe in my last letter I related my experiences of one period in the trenches – when we stood in eighteen inches of mud for sixteen hours, suffered intensely from the cold, and came out wet through and through.

The conditions were altogether different in the period just completed. I was in the trenches for eleven hours at night. It was a beautiful moonlight night, consequently we had to use extreme care getting in and out in case we should be seen. The trench was perfectly dry, and the only thing that worried us was the cold.

This part of the line is rather advanced, and, therefore, no advantage would be gained by either side advancing at present. Things were very quiet indeed. You will understand how quiet it was when I tell you that we felt more real security in the trenches than in the billets which we occupied a few hundred yards in the rear of our position. Twice whilst there we made preparations to retire to bomb-proof dug-outs. German shells were flying all round us – the other buildings very close to us were hit, but fortunately we escaped.

We are at present enjoying a few days’ rest, but expect to be sent back to the firing-line at any time.

Work in the front line of the trenches is not the hardest part of the campaign. At times we have occupied reserve trenches, where there is nothing to do but keep a good look-out. Cold monotonous work, this!

Then we have a lot of long marching to do from one point of the line to another, which carrying a heavy pack on your back, tires one out more than anything else.

For billets we generally are housed in barns, with or without roofs, but taking everything into account, we fare pretty well in this respect.

The school magazine, March 1915

Arthur Wolfe wrote this on 4 March 1915. He was killed one week later.

2nd Lieutenant Henry Budden has a ‘marvellous escape’

I am now second in command of a battery of trench Howitzers attached to the 8th Division, and very nice little toys they are too. We have four guns, which throw quite a decent-sized shell filled with shrapnel, and they have an explosion like a 6-inch Howitzer.