9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

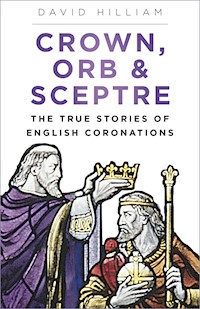

Coronations are very public occasions, typically seen as meticulously planned formal ceremonies where everything runs smoothly. But behind the scenes at Westminster Abbey lie extraordinary but true stories of mayhem, confusion and merriment. In this book we travel through over a thousand years of England's history to reveal the real character of its kings and queens. Also packed with facts about how the service, traditions and accessories have changed over the years, Crown, Orb & Sceptre provides both a compelling read and an accessible and irreverent reference guide to one of the most spectacular ceremonies in England's heritage.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

CROWN, ORB & SCEPTRE

CROWN, ORB & SCEPTRE

THE TRUE STORIES OF ENGLISH CORONATIONS

DAVID HILLIAM

First published 2001 Paperback edition first published 2002 This edition first published 2009

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved © David Hilliam, 2001, 2002, 2009, 2011

The right of David Hilliam, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7079 5

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7080 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Preface

1. Coronations Before the Conquest

Kingston’s ‘Coronation Stone’

2. Coronations from William the Conqueror to Elizabeth II

The Origins of the Stone of Scone

The Knights of the Bath

Inventory of Regalia, 1649

300 Years of Robe-Making

Coronation Music and Musicians

The Coronation Robes

The Stone Returned to Scotland After 700 Years

3. The Crown Jewels

The Story of the Koh-i-Noor Diamond

4. The Honours of Scotland

5. How Colonel Blood Stole the Crown Jewels from the Tower of London

Appendix A: Genealogical Chart of the English Monarchy

Appendix B: The Order of the Coronation Service

Bibliography

Preface

This book covers a thousand years of English coronations. It describes the ceremonial occasions when kings and queens have been anointed, crowned, enthroned – and thereby become entitled to loyalty and obedience.

Traditionally, the accession of a new monarch is announced with stark and brutal simplicity – ‘The King is dead! Long live the King!’ – the essential feature about this being that everyone knows without a shred of doubt who the next monarch will be.

No need for lengthy election campaigns; no frantic jostlings for position; no power vacuums; no fuss. Seamlessly, power passes to the next in line. Accessions simply happen. Coronations follow, often after months of elaborate preparation.

Of course, there have been moments of high drama, when usurpers have seized power, or when an unexpected crisis has occurred; but whatever the circumstances, every new monarch needs to be crowned.

And every crowning is unique. With the arrival of a new monarch, there is an inevitable sense of newness, curiosity and hope. There is always an indefinable shift of mood throughout the nation as a new reign begins.

Coronations of Saxon kings took place in various holy places, but since 1066, the ‘year of three kings’, all English kings and queens have been crowned at Westminster Abbey. Only two kings were never crowned: Edward V who disappeared, probably murdered in the Tower of London; and Edward VIII who abdicated.

Here is an attempt to recapture something of the spirit of all those coronations – from the time when Archbishop Dunstan crowned Edgar in Bath Abbey in the year 973, to that memorable occasion nearly ten centuries years later, when millions of people witnessed the televised coronation of Elizabeth II on 2 June 1953.

1

Coronations Before the Conquest

THE HERMIT-WIZARD FROM GLASTONBURY AND A RUNAWAY HORSE

We owe the English coronation service to one of the most colourful characters of the early Middle Ages – the great tenthcentury archbishop and adviser to Saxon kings, Saint Dunstan. He was born in AD 909, just ten years after the death of King Alfred. It is likely that Dunstan himself was a minor member of the Saxon royal family, growing up in the court of Alfred’s grandson, King Athelstan, at Glastonbury. This was at a time well before London was considered to be the capital of the country, and more than a century before Westminster Abbey was even begun.

As a teenager, young Dunstan was given a good education by the monks at Glastonbury, and he seems to have had an enquiring mind and many artistic talents; in fact he gained the reputation of being something of an eccentric among his contemporaries. He loved painting, embroidery, music, and he enjoyed reading whatever books he could find on poetry, legends and all sorts of out-of-the-way subjects. Added to this, he had strange dreams and visions that he enjoyed describing in great detail.

Eventually, his rather oddball lifestyle seems to have irritated his more normal hunting-and-fighting companions so much that they conspired to get rid of him, and they complained to Athelstan that Dunstan was a wizard! His enemies became so insistent that eventually Athelstan gave way to them and banished young Dunstan from his court on the charge of practising witchcraft and unlawful arts. The story goes that as he left he was pursued by the mob, who rolled him in mud, kicked him and beat him up.

For a while, Dunstan became a hermit, quietly practising his music, reading, and specialising in metal-working. He built himself a tiny cell, only 5 ft long and 2½ ft wide, where he would pray and enjoy his heavenly visions. A famous incident is said to have happened one day, as he was working at his forge he was visited by the devil, who tried to tempt him by making lewd conversations about sexual pleasures with women. Dunstan was so horrified that he heated his pincers until they were red hot and then suddenly grabbed the devil’s nose with them so that the ‘evil one’ ran off screaming with pain. In Christian art, Dunstan is often depicted holding those pincers, and he is still regarded as the patron saint of goldsmiths, jewellers and locksmiths.

When Athelstan died, Dunstan was brought back to court by the new king, Edmund, but soon the old rumours about witchcraft began to circulate again, so that Dunstan was banned for a second time. He was so upset by this that he decided to go abroad and live in Germany. He was just preparing to leave the country, when an incident occurred at Cheddar Gorge, in Somerset, that was to change his luck dramatically – and, more importantly, the repercussions of this incident would change the course of English history.

One day, King Edmund was hunting at the top of the cliffs at Cheddar Gorge. As anyone knows who has been there, Cheddar is famous not only for its cheese but also for its deep, dangerous, rocky chasm, with steep vertical precipices on each side of a craggy valley. Today it is a popular tourist attraction, with its stalagmite caves and picturesque rockfaces. Edmund was chasing a deer when his horse began to gallop headlong and uncontrollably towards the brink of this chasm, and horse and rider seemed certain to plunge into the gorge beneath. Desperately, the king began to pray, vowing that he would redress the wrongs done to Dunstan if only his life were to be spared, and that he would for ever after hold Dunstan in great honour. Miraculously, the horse managed to save itself and Edmund survived; and thanks to this dramatic episode Dunstan was immediately appointed to be Abbot of Glastonbury – the first rung on a ladder of success which later enabled him to become, in succession, Bishop of Worcester, Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury.

Edmund reigned for only seven years before being stabbed to death by an outlawed thief. His brother, King Edred, who succeeded him, reigned for only nine years, fighting off the Danish armies of Eric Bloodaxe before his own premature death at about thirty-two. Edred was followed on the throne by a silly and incompetent fifteen-year-old, King Edwy, who was to last only about four years before he too was murdered.

It was at Edwy’s crowning ceremony, which took place at Kingston upon Thames in AD 955, that Dunstan – still Abbot of Glastonbury – was involved in one of the most notoriously embarrassing incidents ever to take place at an English coronation. Young Edwy, nephew of his predecessor King Edred, obviously felt that as king he could do just as he liked, and at his coronation feast he abruptly left the royal banquet to have sex in a nearby room with a lady friend and her daughter. When the nobles and Archbishop Odo of Canterbury realised just what was happening, they were suitably scandalised, and deputed Dunstan and the Bishop of Lichfield to go and fetch the newly-crowned king back to table. A medieval chronicler describes with ill-concealed glee how, when Dunstan and the bishop entered, they found Edwy ‘repeatedly wallowing between the two of them in evil fashion, as if in a vile sty.’ Apparently, the royal crown, ‘bound with wondrous metal, gold and silver and gems’, had been carelessly thrown down on to the floor. Dunstan is said to have thrust this crown back on the lustful teenager’s head and to have literally dragged him back to the coronation banquet, giving him a sound telling off as he did so. Naturally enough, King Edwy was not exactly pleased by this, and Dunstan found it necessary to retire abroad to Flanders for the rest of Edwy’s reign. However, this exile in Ghent was to prove immensely important for the future history of Christianity in England, for it was here that Dunstan encountered at first hand the Benedictine monastic way of life. It seized his imagination, and he was determined to introduce it to monasteries in England if ever he were to return.

Edwy’s sheer incompetence led to his downfall and probable murder in AD 959, and his more successful brother Edgar was elected to take over the kingdom. It was a turning point in English history; King Edgar brought stability and prosperity to the country – he was known as Edgar the Peaceful.

One of Edgar’s first acts was to bring back Dunstan and make him Archbishop of Canterbury. At fifty Dunstan was a relatively old man, but now at last he was able to wield genuine power and his real career was just about to begin. He became Edgar’s chief adviser in both religious and secular matters, and both men were deeply committed to strengthening the church. Together they founded over forty religious houses, encouraging learning and culture and supporting the monastic system throughout the land. Dunstan’s experience in Flanders led him to introduce Benedictine discipline wherever possible. Edgar had a gift for appointing outstanding advisers, and in this great period of expansion he was also helped by Oswald, whom he made Archbishop of York, and Aethelwold, whom he appointed to be Bishop of Winchester.

These devout churchmen had a profound effect upon the time in which they lived; indeed, their work led to what has been called the ‘tenth century reformation’ – mostly thanks to the influence of Dunstan, the ex-hermit of Glastonbury. For us, however, the crucial importance of Dunstan in the history of English coronations is paramount. Dunstan crowned Edgar the Peaceful fourteen years after the king came to the throne.

DUNSTAN CROWNS AND ANOINTS KING EDGAR IN 973

Reigned 957–75, crowned May 973

A Thousand-Year-Old Tradition is Begun

Edgar stands out as one of the great Saxon kings: wise, innovative, devout, serenely sure of himself, and so much a king among kings that the famous occasion at which he was rowed in state on the River Dee by seven Welsh and Scottish kings has been depicted again and again by artists over the centuries. Therefore, it comes as something of a surprise to realise that he was aged only about fifteen when the Northumbrians and Mercians made him their king in 957 even while his elder brother, the wretched Edwy, was still on the throne. Two years later, in 959, Edwy’s death ensured that Edgar became King of all England, still aged only seventeen.

Edgar’s immediate recall of Dunstan from exile, making him Bishop of Worcester in 957, Bishop of London in 959 and then Archbishop of Canterbury in 960, showed that he knew exactly who he intended to rely on for advice. For the rest of his reign the two men must have been frenetically energetic in planning and founding dozens of abbeys and religious foundations throughout the kingdom. There were, of course, the other usual kingly jobs to attend to – fighting the Welsh; strengthening the navy; ridding the country of wolves; reorganising the circulation of currency by doubling the number of mints to sixty; marrying twice and begetting the necessary heirs. However, it is probably true to say that from the age of fifteen to thirty his main preoccupation was the peaceful settlement of the country with an ever-increasing number of monasteries.

However, during the first fourteen years of his reign, he still remained uncrowned. It was not until May 973 that King Edgar, by now aged thirty and with an exceptionally successful reign behind him, allowed himself to be crowned in a supremely magnificent ceremony at Bath. Naturally enough, the order of service of 973 was specially drawn up by Archbishop Dunstan – a very special service, worthy of such a pious and noble monarch. But at the time neither of them could know that this order of service would become the basis and foundation for all subsequent English coronation services for centuries to come – even to include the coronation of Elizabeth II, nearly a thousand years later, in 1953.

Why, then, did Edgar delay so long? What was it that was to make this coronation service so special? And what, in essence, did Dunstan devise, that could last so long?

Dunstan knew that on the continent, in the Frankish monarchy, a ceremony had emerged, sanctioned by the pope, which involved the sacred practice of anointing a new king. Up until then, kings in England had never as yet received this special distinction.† Crowned they may have been, but for Dunstan, as he planned the coronation of his close friend, King Edgar, this was not enough. The addition of holy oil poured over a royal head and body would make the sovereign much more than a secular ruler. Anointed, a new king would become a priest as well. The implications of this were intriguing. Clearly, the prestige of kingship was being enhanced and at the same time a strong link between church and secular state was being forged, which arguably also enhanced the position of the church. Whatever else the ceremony signified, it made the king divine, unique, and such an anointing brought to mind biblical traditions which could be traced back to when King Solomon was annointed by Zadok the priest and the prophet Nathan.

The reason for the long delay before King Edgar’s coronation can now be seen, for it was not until 973 that Edgar reached the age of thirty – the minimum age for the priesthood. It is now generally agreed that this ‘coming of age’ lay behind the coronation in which Archbishop Dunstan, assisted by Archbishop Oswald of York, solemnly anointed Edgar king in a service significantly containing the biblical text, ‘Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet anointed Solomon King,’ – a text which has been recited and sung at coronations ever since. Handel’s great anthem seven and a half centuries later served to remind later generations that the anointing is the crucially meaningful moment at a coronation.

Edgar entered the abbey wearing his crown, which he then laid aside as he knelt before the altar. Repeating words spoken by Dunstan, he took his three-fold oath: that the Church of God and all Christian people should enjoy true peace for ever; that he would forbid all wrong and all robbery to all degrees; and that he would command justice and mercy in all judgements. It must have been an impressive ceremony. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle bursts into poetic rapture as it describes how

In this year, Edgar, ruler of the English, Was consecrated king by a great assembly, In the ancient city of Acemannesceaster, Also called Bath by the inhabitants Of this island. On that blessed day,Called and named Whit Sunday by the children of men, There was great rejoicing by all. As I have heard, There was a great congregation of priests, and a goodly company of monks, And wise men gathered together.

. . . Almost one thousand years had elapsed Since the time of the Lord of Victories when this happened. Edmund’s son, the valiant in warlike deeds, Had spent twenty-nine years in the world when this took place. He was in his thirtieth year when consecrated king.

Bath is a city filled with memories and physical remains of Imperial Rome, lying about twenty-five miles from Cheddar Gorge and Glastonbury. The area was well known to both Dunstan and Edgar, and perhaps the choice of Bath came from a desire to remind everyone that this was a place where emperors had dwelt.

Sadly, nothing remains nowadays of the original abbey where that coronation took place. The present abbey was not begun until the eleventh century. However, there is a commemorative stained-glass window there, showing not only Edgar’s coronation, but also the famous incident when he was rowed, shortly afterwards, on the River Dee by seven Scottish and Welsh kings. If that legendary event really did take place, there would have been no doubt in their minds that Edgar’s sacred anointing invested him with unique authority, direct from God.

Unfortunately, Edgar lived for only another two years after his coronation, and died aged thirty-two. It had been an exceptionally important reign, and his early death was to plunge England into yet another period of chaos, made even worse by constant invasions by the Danes. However, Dunstan lived on, and having officiated at the funeral of King Edgar, burying him at Glastonbury, he survived into the reigns of Edgar’s two sons, Edward and Ethelred, born of each of Edgar’s two wives.

Edward (known as ‘the Martyr’) succeeded Edgar in 975, but he was only about twelve at the time, and was murdered at Corfe Castle in 978, almost three years later, aged fifteen. It is unclear whether this unfortunate young king was ever crowned, although a coronation may have taken place at Kingston upon Thames. It is known, however, that Dunstan, now nearly seventy, having officiated at Edward the Martyr’s funeral in Shaftesbury Abbey, went on to crown Edward’s half-brother, Ethelred (known as ‘the Unready’) at Kingston upon Thames. Unfortunately, no details about this coronation survive.

However, Ethelred obviously had no time for Dunstan, who was now forced out of any active involvement in politics and retired to live quietly in Canterbury: teaching, reading, correcting manuscripts and visiting the tombs of Saxon saints in the middle of the night. It was a happy retirement, and when he died in 988 he was immediately revered as a saint. For centuries afterwards Canterbury schoolboys would pray to St Dunstan if ever they were in danger of being whipped. It has been said that the tenth century gave shape to English history and that Dunstan gave shape to the tenth century. He lived through the reigns of seven Saxon kings and achieved great things. Certainly, the most enduring of all St Dunstan’s works was his Coronation Order of Service, by which, for almost a thousand years, all English kings and queens have been crowned and anointed.

EDMUND II (‘IRONSIDE’) AND THE DANISH KINGS

The death of Ethelred (‘the Unready’) in April 1016 heralded a period of uncertainty about the monarchy until the Danes finally gained full control. Ethelred’s son, Edmund II, was chosen to be king by the members of the Witan (the Anglo-Saxon forerunner of parliament) resident in London, while the Witan majority at Southampton had little choice other than having to choose Canute (Cnut).

Records of the coronations of Edmund II and the Danish kings are understandably scanty. Westminster Abbey had yet to be built, and the growing tradition of holding coronations at Kingston upon Thames was broken. Edmund and the Danish kings who followed him were crowned at various locations:

KINGSTON’S ‘CORONATION STONE’

Kingston upon Thames, about twelve miles west of London, is reputedly the place where Saxon kings had their coronations. In the middle of the town, visible for all to see, is a large lump of sandstone, surrounded by robust, blue-painted iron railings. The stone is roughly cube-shaped, about 4 ft square, resting on a sevensided plinth. Boldly carved round the base of the plinth are the names of no fewer than seven Saxon kings who are said to have been crowned on Kingston’s famous coronation stone: Edward the Elder, Athelstan, Edmund, Eadred, Eadwig, Edward the Martyr, Aethelred. Intriguingly, it has even been claimed that the very name Kingston derives from King’s Stone.

However, apart from Edgar’s famous coronation in Bath, it is simply not known where many of the Saxon kings were crowned. Certainly, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which is our most reliable source of information, tells us of two coronations at Kingston: that of Athelstan in AD 925, and Ethelred the Unready in AD 979. The tradition that other kings were crowned at Kingston comes exclusively from the thirteenth-century Dean of St Paul’s, Ralph de Diceto, who seems to have added the other kings to the list, without any evidence at all.

Edred, and possibly Edwy, may have also been crowned at Kingston – that is, if we can take the word of another medieval chronicler, Florence of Worcester. However, once again, the writer lived long after the events he was recording, and there is no complete certainty about his claims. John Leland in the sixteenth century makes the point that the citizens of Kingston claim ‘certen knowlege of a few kinges crounid ther afore the Conqueste; and contende that 2 or 3 kinges were buried yn their paroche chirch’. But with the commendable scepticism of a true historian, he adds: ‘but they can not bring no profe nor liklihood of it’!

As for the coronation stone itself, there is no reliable information at all prior to 1850 when, in the words of Shaan Butters, who has recently researched the matter, it was rescued ‘from obscurity and publicly inaugurated as an historic monument’. Sadly, there is no reference to a stone before 1793, when The British Directory claims that ‘some of our Saxon kings were also crowned here; and close to the north side of the church is a large stone, on which, according to tradition, they were placed during the ceremony’. It was not until 1850 that it was moved to its present location and enclosed in the ‘Saxon effect’ railings that we can still see today.

Edmund II (‘Ironside’) (1016)

Crowned in Old St Paul’s, London, April 1016

Canute (1016–35)

Crowned in Old St Paul’s, London, 6 January 1017

Harold I (‘Harefoot’) (1035–40)

Crowned at Oxford, 1037

Hardecanute (1040–42)

Crowned in Canterbury Cathedral, 18 June 1040

At the death of Hardecanute, his half-brother Edward the Confessor – son of Ethelred the Unready and Queen Emma – was brought back from Normandy to become king, and he chose to be crowned in Winchester, the capital of Wessex, on 3 April 1043. It was to be the last coronation not in Westminster Abbey.

EDWARD THE CONFESSOR BREAKS HIS VOW TO GO TO ROME

When the last of the Danish Kings, Hardecanute, aged about twenty-three, choked himself to death at someone’s weddingfeast in the summer of 1042, no one mourned. His was a short and brutal reign. He was probably poisoned.

The man who was now invited to become king could hardly have been more different – Edward, the monkish, saintly son of Ethelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy. Edward had been born in Islip, a tiny village in Oxfordshire, but when he was only ten the Danish invasion had forced his father Ethelred to flee the country and seek refuge in Normandy. Young Edward had gone with him and after his father’s death he had continued to live there in exile throughout the Danish occupation of the English throne. To all intents and purposes Edward was now a Norman, although by birth he belonged to the ancient Saxon line of kings. Edward always realised that there was a slim chance of his becoming king of England, but he hardly realised how soon it would be. Hardecanute’s sudden and unexpected death propelled him surprisingly quickly to the throne.

He was about thirty-nine, with an exceptionally red face, but otherwise snow-white skin, hair and beard. He was tall, and was described as having long, almost translucent fingers. It has been suggested that he was an albino. The most noticeable feature about him, however, was his deeply religious lifestyle. An early writer tells how he loved talking with monks and abbots, and particularly ‘used to stand with lamb-like meekness and tranquil mind at the holy masses’. The very name that people gave him, ‘Confessor’, suggests that he was regarded more as a priest than as a king. Those long fingers of his were used to heal the sick, who came to him in large numbers to be ‘touched’ by them. Shakespeare mentions the Confessor’s holy gift of healing in Macbeth. Early on in his life Edward had taken a vow of chastity, and was believed to have refused to consummate his marriage to Edith, daughter of Godwin, Earl of Wessex.

Edward the Confessor had also made another vow. He had sworn that if ever he were to be made king of England he would make a pilgrimage to Rome to visit the place where his favourite saint, St Peter, was buried. He hoped that St Peter’s successor, the pope, would anoint him. Accordingly, when he came to the throne he announced his intention of going to Rome and fulfilling this vow. However, the members of the Great Council were horrified. They had just lost three Danish kings in quick succession and now that they had managed to get a king of the ancient Saxon blood-line, they certainly did not want to run the risk of losing him on a dangerous journey to Italy. They spelled out the perils: bad roads, rough seas, dangerous mountains, ambushes near bridges and fords, and above all the ‘felon Romans, who seek nothing but gain and gifts.’ At last the newlycrowned Edward gave way, and accepted a suggestion that a deputation should be sent to the pope to release him from his vow. The deputation duly set off, saw the pope, and returned with the good news that His Holiness would graciously allow King Edward to forego his oath, on the special condition that he would found or restore a monastery dedicated to St Peter, and that the king himself should become its royal patron. The project seized the Confessor’s mind. The only matter left to decide was where this new abbey should be sited. The great monastery to which Edward the Confessor was to devote the rest of his life was Westminster Abbey.

Nowadays it is almost impossible to cast our minds back to visualise what the area must have looked like when he began this enormous project. The site was a swampy, boggy island situated between two rivulets running down to the River Thames. The island was so thickly covered by thorns and brambles that it had been given the name ‘Isle of Thorns’. Far from being the densely built-up area we know today, it was completely desolate, miles from the small city of London, and apart from a couple of springs and a plentiful supply of fish from the Thames, it was without any apparently redeeming feature. Years before, King Offa of Mercia had seen this patch of marshy scrubland and had called it ‘a terrible place’.

There had been some form of early settlement, possibly dating as far back as Roman times, and an earlier small monastery had grown up there, traditionally built in 616 by the newly-converted King Sebert, third king of the Saxon Kingdom of Essex. Dunstan, in the previous century, had helped to establish this more firmly, so that in his time twelve monks had dwelt and prayed there, prompting the citizens of London to call it the ‘Western Monastery’ or ‘Minster of the West’. Thus the name of ‘Westminster’ was born. Even so, by the time Edward the Confessor came to the throne in 1042 this outlying religious settlement had been destroyed by the marauding Danes and had almost been forgotten. Quite by coincidence the ancient monastery had been dedicated to St Peter – the very saint in whose honour King Edward was bound to build or re-found a great new abbey. All sorts of legends connected with St Peter now began to be linked with this holy spot, embellishing the thought, in some form or other, that St Peter himself had founded it and was personally linked to the place. A bishop had a dream . . . a hermit had a vision . . .

Whatever the deciding factor may have been, Edward the Confessor began to construct a vast new abbey on this rather peculiarly-chosen site almost as soon as he came to the throne in 1042. Thereafter, for almost a quarter of a century, until his death in 1066, he spent large sums of money and devoted boundless energy to creating what was, at that time, one of the largest abbeys in Christendom. Of equal importance, in order to supervise this great enterprise, Edward the Confessor now frequently began to live in Westminster rather than in the ancient capital of Winchester, so it was inevitable that a palace and other royal buildings should soon grow up alongside the new abbey. Thus abbey and palace developed together, so that Westminster gradually became what it is today, the centre of government as well as the focus of royal religious ceremony.

It is sad to record that Edward the Confessor never lived to see his new abbey take its central place in the life of the nation. After a lifetime spent on this great project he fell ill towards the end of 1065, just as plans were being finalised to consecrate the building.

He had arrived at Westminster and tried to take part in the Christmas celebrations, but it was clear to everyone that he had only days to live. His health collapsed on the Feast of St John, 27 December. Quickly he ordered that the consecration should be brought forward, to the following day, the Feast of the Holy Innocents. However, by then he was so weak that he could not rise from his bed. He only just managed to sign the Charter of the Foundation. His consort, Queen Edith, represented him at the consecration, accompanied by her two brothers, Harold and Gurth. It must have been a profound disappointment to the Confessor not to be there himself. He lay, slipping from delirium into unconsciousness over the next few days in his new Palace of Westminster, until at last, on 5 January, he died. . . . It was the fatal year, 1066.

1066 – A YEAR OF THREE KINGS

Within days of being consecrated, the newly-built Westminster Abbey received the body of its founder into its sacred keeping. He lies there still. England needed a new king, and although Edward had no son, it was apparent to many – but not all – that his brother-in-law Harold was the obvious choice. Throughout his reign the Confessor had relied heavily on Harold to rule the kingdom while he himself was busy with his religious building programme. As for Harold, he was only too keen to take over the throne – almost too keen, for he quickly gathered together all those members of the Witan who were at the old king’s funeral and with indecent haste he managed to get himself elected, literally within hours of the Confessor’s death. It was opportunism at its most blatant.

However, a few years earlier Harold had promised William, Duke of Normandy that he would support the future Conqueror’s claim to the English throne. Indeed, he had made that promise in public, solemnly swearing fealty to William. It was an oath before God. Moreover, it was thought by many that before his death Edward the Confessor himself had nominated the duke as his heir. The situation was clear. Everyone knew that Harold was seizing the throne in defiance of the Almighty; possibly in defiance of the wishes of the Confessor; and certainly in defiance of the warlike Duke of Normandy. It was a collision-course that was bound to lead to conflict. However, in January 1066, the fatal Battle of Hastings was still nine months away.

Immediately after the death of the Confessor Harold took charge of the situation and ordered the burial of the dead king for the very next morning. It has been said that in actual fact Harold had already reigned for thirteen years, and people naturally looked to him for leadership. The old king had carefully chosen the spot where he should be buried – in front of the altar of St Peter. Here, then, was where he was laid to rest, wearing a pilgrim’s ring on one of his pale fingers and, possibly, the crown of England upon his snow-white head.

It was on the Feast of the Epiphany, Friday 6 January 1066, that the first of the year’s three kings was buried. Bells tolled, black-robed Benedictine monks chanted psalms, and in the dark, early hours of the morning, just as dawn was breaking, the slow procession of churchmen and Saxon nobles bore the precious corpse to its final resting place. Westminster Abbey was now the home of England’s most holy king. Miracles were expected as a matter of course. Then, as soon as the funeral rites had been completed, the little gathering returned to the palace buildings to prepare for a second ceremony – a coronation. Such preparations would necessarily be hasty, for Harold had decided to act swiftly, relying only on those Saxon supporters who were still around him. There was no need to invite nobles who dwelt in more distant parts of the kingdom. Who knows what their opinions might be about who should be king? Perhaps it would be wiser not to ask. Accordingly, about noon on that same Feast of the Epiphany, Harold and his supporters entered Westminster Abbey for a second time that day.

Details of this coronation are vague. Quite probably Harold was crowned by Ealdred, Archbishop of York. Stigand, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was held to be discredited because he had received his pallium (the holy vestment which symbolised the authority granted to him from the pope) from the antipope, Benedict X. Later on, the Normans spread the rumour that Stigand had crowned Harold – thus rendering his coronation invalid. Whatever the details, Harold emerged from Westminster Abbey as king – the second king to rule England in the year 1066.

With hindsight, we can see that the importance of this first coronation in Westminster Abbey was not any particular detail, but the very fact that it took place where it did, thus setting a precedent for others to follow. Therefore, when William, Duke of Normandy, won his great victory at Hastings in the following October, becoming the third English king in that memorable year, it was inevitable that he should look to the most significant place in the kingdom in which he too could be crowned. What place could be more significant than Westminster, the resting place of his holy uncle, Edward the Confessor, and the site where his rival, the promise-breaking Harold, had been crowned?

So it was that on Christmas Day 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, duly came to Westminster to to be crowned in the Confessor’s abbey. From Harold and William to Elizabeth II this line has been unbroken. Since 1066, with the two exceptions of the uncrowned Edward V, who was probably murdered in the Tower of London, and Edward VIII, also uncrowned, who abdicated to marry Wallis Simpson, every king and every reigning queen has been crowned and anointed there, all largely following the Order of Service devised by Archbishop Dunstan in Bath for the crowning and anointing of King Edgar in 973.

† Details of crowning ceremonies before the coronation of King Edgar are scanty. In England there was one example of the practice of anointing a new king from 785, when King Offa of Mercia had had his son Egfrith anointed and declared his successor. Egfrith survived his father by only four months and is almost totally forgotten nowadays. Nevertheless, he should be remembered here as he was probably the first king on English soil – albeit a very minor, local Saxon king – to be anointed. However, Edgar seems to have been the first king of all England to be anointed. The circumstances of Edgar’s high-profile coronation gave solemn, added significance to this practice of anointing.

2

Coronations from William the Conqueror to Elizabeth II

WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR

Reigned 1066–87, crowned 25 December 1066, aged about 38

Panic and Fire!

William had won the Battle of Hastings in October, and in the ten weeks following he had moved cautiously, partly expecting to meet further resistance. However, at least for the time being, he had won total victory over the Saxons. All the same, he trod warily, taking Dover, so as to preserve his escape route should the need arise, and accepting the keys of Winchester and its treasury from Edith, widow of Edward the Confessor, who had retired to the ancient capital.

At length, after the Saxon nobles and church digitaries had gathered to discuss the situation urgently among themselves, William met them at Berkhamstead, where he received their submission and an oath of fealty from the one person who still had hereditary claim to the English throne – Edmund Ironside’s grandson, Edgar the Atheling. Edgar was only fifteen, and to have continued opposing William at this late stage would have been sheer folly. After accepting this formal surrender, William pressed on to London and with the collapse of any further resistance, he found himself in full command of the country. Clearly, the inevitable next step was to have himself crowned. Although he himself would have preferred to wait until his wife Matilda could join him, his Norman entourage urged him to move quickly and arrange a coronation for himself. Only then could he claim legitimate kingship over the land he had just seized by force. Hence it was, on Christmas Day 1066, that Westminster Abbey witnessed its second coronation within a year.

A common idea about William, Duke of Normandy is that he was a blustering but successful adventurer, an interloper rather like Napoleon would have been if he had managed to cross the channel. In fact, William considered that he had two claims to the English throne: firstly through his kinship with Emma, mother of Edward the Confessor, and secondly because both Edward the Confessor and Harold had promised him that he should be their successor. In William’s eyes, it had been Harold who had been the promise-breaking interloper. Not only did William believe himself morally entitled to become king, but also the pope himself had given his holy approval to the venture. He had sent William a special banner, a sacred ‘pallium’, which he had personally blessed. With such support, William entered Westminster Abbey with an easy conscience, surrounded by his conquering companions. Stigand, the Saxon Archbishop of Canterbury, was not recognised by Rome, as he had received office uncanonically through the antipope, Benedict X, so William chose to be crowned and anointed by Eldred, Archbishop of York, with Bishop Geoffrey of Coutances helping to officiate. The discredited Stigand was allowed to be present – after all, William did not wish to cause offence.

A new crown had been made for the conqueror, the head of a new dynasty. However, to show continuity the coronation service followed the traditional form devised by Dunstan for King Edgar a century before. Only in one respect was it felt necessary to make changes, for the very practical reason that there were two groups of supporters in the abbey, Saxon and Norman, each with their own language. It was planned, therefore, that when the time came for the question asking the assembled congregation whether they were prepared to accept William as their lawful king, the ‘Recognition’ would be declaimed in both languages.

Archbishop Eldred put the question first in the Old English of the Saxons, and then this was followed by Geoffrey of Coutances asking the same question in Norman French. The resulting shouts were terrifyingly loud. Possibly, the two groups of people were trying to outdo each other; perhaps the Saxons were wanting to prove that they really did support the new dynasty; and quite probably the Normans were shouting with all the lusty support of a winning football crowd. Whatever the reason, the fierce acclamation ‘Yea, yea, King William!’reached the Norman soldiers who were trying to keep order in the crowds outside. The shouts inside the abbey so alarmed the Norman soldiers standing guard outside that they drew the conclusion that the new king was being assassinated. It is a measure of the tension that surrounded the whole affair. Their immediate response was to set fire to all the thatched, wooden houses surrounding the abbey. Quickly a riot ensued. We have a near-contemporary account of the affair by a Norman chronicler, Ordericus Vitalis, whose father was probably an eye-witness:

The armed guard outside, hearing the tumult of the joyful crowd in the church and the harsh accents of a foreign tongue, imagined that some treachery was on foot, and rashly set fire to some of the buildings. The fire spread rapidly from house to house; the crowd who had been rejoicing in the church took fright and throngs of men and women of every rank and condition rushed out of the church in frantic haste.

Only the bishops and a few clergy and monks remained, terrified, in the sanctuary, and with difficulty completed the consecration of the king who was trembling from head to foot. Almost all the rest made for the scene of conflagration: some to fight the flames, and many others hoping to find loot for themselves in the general confusion.

The English, after hearing of the perpetration of such misdeeds, never again trusted the Normans who seemed to have betrayed them, but nursed their anger and bided their time for revenge.

To do him justice, William was upset by this turn of events and is reported to have personally visited those who had suffered as a result of the fire.

Nevertheless, despite the shambles of this rather inauspicious beginning, William had been crowned and anointed. He had already demonstrated his military might, but now, after this momentous Christmas Day, he was divinely and legally empowered to rule. It now remained for him to bring his diminutive wife (Matilda was just over 4 ft tall) to be crowned and anointed as his consort.

MATILDA, QUEEN OF WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR

Dates as Queen 1068–83, crowned 11 May 1068, aged about 37

Enter Robert de Marmion, The Queen’s Champion

It was not until April 1068 that William’s wife Matilda crossed the channel to be crowned as his queen. She was crowned at a magnificent ceremony in the old Saxon cathedral in Winchester, soon to be wantonly pulled down by the victorious Normans in order to make room for the much bigger cathedral we see there today.

This old minster was one of the most beautiful buildings in the country, especially important because it was the burialplace of the Saxon kings and of the Danish King Canute. Legend has it that Canute had placed his golden crown above the altar here, to remind people that it was God alone, the King of Heaven, and no earthly king who could be presumed to rule the incoming tides. The sacred remains of many saints rested there too, chief among them being St Swithun, whose bones had caused such dramatic wet weather when, against his wishes, they had been moved inside the building. St Swithun’s memory is still very much alive in Winchester today.

The coronation of Matilda was an important innovation in England. The wives of Saxon kings before the conquest were not usually honoured in this way, so this was something of a novelty. Whatever the onlookers may have thought, it was clear that William was willing to share power with his consort, as was the custom on the continent. Accordingly, his duchess was crowned and anointed on Whit Sunday, 1068. William took the opportunity to wear his own crown too, and ‘crown-wearings’ became one of his regular and looked-for customs. The conqueror regularly spent Christmas at Gloucester with his court, Easter at Winchester, and Whitsuntide at Westminster. Crownwearings were a part of the ceremonies on all these occasions.

It was at the coronation of Matilda that yet another famous tradition was begun: the introduction of the king’s (or in this case the queen’s) champion. Just as the assembled guests were sitting down to the coronation feast after the cathedral service, the meal was interrupted by the arrival of a knight on horseback who rode into the hall boldly declaring: ‘If any person denies that our most gracious sovereign, Lord William, and his spouse Matilda, are king and queen of England, he is a false-hearted traitor and a liar; and here, I, as Champion, do challenge him to single combat.’ The challenge was repeated three times, but of course no one dared to meet it, and so in this manner Matilda became undisputed queen. The bold challenger was Robert de Marmion, one of William’s entourage, and the office of ‘Champion’ was granted to him together with the lands of Fontenaye in Normandy and the manor of Scrivelsby, near Horncastle, in Lincolnshire. The custom of having a champion to make such a challenge was of Norman origin, and until this moment quite unknown in England. Luckily for Marmion, it was a hereditary office, which could be passed down even through the female line. The office of champion eventually passed in the fourteenth century to the Dymoke family, who have proudly been champions of England through the centuries, even taking part in the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953.

William was in an expansive mood at that Whitsun coronation, even giving the manor of Addington to Tezelin, his cook, for devising a dish of specially delectable soup called dillegrout for the coronation banquet. Life was good for the royal pair: Duke and Duchess of Normandy; King and Queen of England; crowned and anointed with holy oil; three healthy sons; and Matilda was pregnant yet again. She was due to produce the future Henry I in the autumn. Two reigns later the timing of that pregnancy was to be specially significant.

WILLIAM II (‘RUFUS’)

Reigned 1087–1100, crowned 26 September 1087, aged about 31

‘King Robert’ Misses Out

William the Conqueror died in Rouen, France, on 10 September 1087, after sustaining severe internal injuries when his horse had reared and his vast belly had been thrust forward against the pommel of his saddle. The conqueror lay in mortal pain, deciding how to dispose of his estate, and finally wrote a will bequeathing Normandy to his eldest son, Robert, and England to the next son, red-faced, ginger-haired William Rufus. As for his youngest son, Henry, who was then aged only nineteen, he rather stingily gave him a mere £5,000 in silver.

Rufus inherited the throne of England. But it was a debatable choice. If the rights of eldest sons were to be upheld, surely it ought to have been Robert Curthose, and a number of the baronage would have preferred Robert to Rufus. The deciding mind was that of Lanfranc, appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by William the Conqueror as successor to the hapless and unrecognised Stigand. Even before William died, Rufus hastened across the channel to Lanfranc, carrying his father’s will, and was able to persuade him that he should be crowned forthwith as the conqueror had wished. Robert was still in France, staying with his father’s old enemy, King Philip, and had been estranged from his father for some years. To Rufus’s relief, Lanfranc accepted the Conqueror’s will, and before his elder brother Robert could mount a challenge, Rufus had himself crowned in Westminster Abbey.

For us, the important thing about this coronation is that it was in Westminster Abbey. It was the third time the abbey had been chosen, and henceforth was to become the accepted and traditional place for coronations, just as Rheims in France and Aachen in Germany.