Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

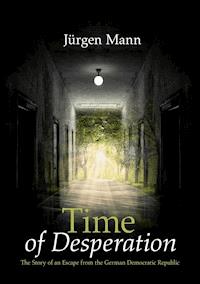

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Sondershausen, a small town in East Germany in 1959: Together with their sons Roland and Jürgen, Ferdi and Helga Mann lead a happy life. Then one day, an in itself trifling event brings an abrupt change to the familys peaceful existence: Ferdi, who works as a criminal investigation officer, happens to fall asleep during shift, an incident costing him his rank. And while after deciding to leave the police service, Ferdi finds a new position. The recent developments have bluntly confronted the couple, by now expecting twins, with the sobering reality of the regimes insidious surveillance practices. Never convinced by the political system in the first place, the present situation is all it takes to rekindle Ferdis and Helgas urge to leave the country, a country so quick to destroy its own peoplesvery future and existence. When soon after, Helga and her by now four children are granted a ten days visa to visit Helgas parents in West Germany, they feel the time has come to bring their longheld plan to fruition. So Ferdi, only two days after his family´s departure, undetected and without any visa, follows them to the West. What they do not know, however, is that the authorities have long cast a wary eye on them and are now sending out their henchmen looking for Ferdi. It is the beginning of a race against time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 515

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

JÜRGEN MANN, born 1951 in Sondershausen / Thuringia, lives since 1961 in West Germany. He studied electro technologies and was thereafter engaged in the management of several international companies, which included also living in the United States for several years. He is married and lives today in Bavaria.

I dedicate this book to my parents

and thank them for being brave, tenacious and courageous

enough to provide a better future

for themselves and their children.

Thank you forever.

Table of Contents

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Epilogue

1.

No doubt, we all were totally excited! We were pretty young boys and girls, my brother Roland, me and all the other school kids from our classes. Roland was ten years old, I was just about seven. He was still in fourth grade, I was still in first. I guess this afternoon would have been appreciated also by a lot of older fellows – not to mention our daddies. You had to love those Red Army soldiers for giving us a never-to-be-forgotten experience.

Our family lived in a small street in the upper town of Sondershausen in Thuringia, Germany. Sondershausen is located about 45 kilometers north of Erfurt, Thuringia’s capital and about the same distance from the Harz Mountain with the famous top, the Brocken. Its plateau was filled with spying radars pointing west. The Brocken was a very restricted area and proof of the Russian presence. You could see signs of their political and strategic influence everywhere.

Another famous nearby location was the Emperor Barbarossa Memorial in Kyffhäuser; this is where you see his massive body sitting on his throne. All is sculptured in red sandstone. He lived in the 12th century and led several crusades to the Holy Land.

At the Potsdam Conference, three months after the end of the Second World War, the Allies agreed to divide Germany. This middle part of Germany, spanning from the Baltic Sea in the north to the border with Czechoslovakia, became the Soviet controlled zone. The eastern part of pre-war Germany, starting east of Frankfurt at the Oder River was given to Poland. It reached to the Baltic States in the northeast and Silesia down in the southeast, almost like a half-moon sickle. At this time, former Middle Germany with states including Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg and the long-term capital Berlin became the new East Germany. Berlin was divided in East and West Berlin. West Berlin became an island and was from then on under the Western Allies’ control; East Berlin under that of the Soviets. Many still called this new East Germany “Middle Germany”, referring to the pre-war situation, or “SBZ”, a German abbreviation for Soviet controlled zone.

Thuringia was a border state to the “free West” and is called the “Green Heart of Germany”: Green certainly – but also hilly and sometimes even a bit mountainous. I would compare it a bit with Oregon but also in parts with the British Midlands. A bit of both and definitely not crowded.

A half a kilometer long street, eight meters wide led to our part of the town. Winding up from the town center, it was named Possenweg after an excursion destination up in the forest: the Possen. The street changed from asphalt to cobble stones and then to an earthen forest road leading further up to the restaurant. It would have taken you about a good hour to walk there. People went there for coffee and cake on weekends, a nice walk through the woods. Before the Possenweg actually entered the forest, climbing up from downtown, it split into two other streets. One to the left, our street, and one to the right.

Upper part of town in both senses: geographically, we were located about 100 meters above the town and if you stood in the middle of the Possenweg looking down toward town, you saw the steeple of the church in the center. At this time, there was no real danger in standing on such a street as there were very few cars or other motor-driven vehicles present.

Up also from the status of the people who lived in our part of the town: most had important positions in the town or in the political party SED and were well established. According to the name, the SED was the Socialist United Party of Germany, but it was actually nothing more than the new communist party.

As already mentioned the Possenweg was interrupted by a round crossing with two streets continuing left and right. Certainly the prettiest part was the one going straight further upwards escorted by old chestnut trees. Turning right would have led you to one of the political centers of the town, the house of the FDGB, an abbreviation for the “Free German Unions”. My parents spent many evenings there listening to the messages the SED thought important to their members and local development. Also further on this street was our public swimming pool.

Our house was the second on the right side after you turned left, number 4 Edmund-König-Strasse. On both sides of our street, wonderful old houses and villas were lined up, most of them in pretty good shape considering it was after the war.

Number four was also an old villa; once it was a one-family home. I call it our house even though we only rented the large basement condo. We had about 75 square meters, two bedrooms, kitchen, living room, cellars and laundry room, a little bathroom but no bathtub. But we had a nice little garden extending from our veranda that was adjacent to our living room. The garden was definitely a nice place for us children to play in. Two old trees, a cherry tree and a willow tree gave us shade in summer time.

There was a bath in the condo on the first floor that was rented by a middle-aged couple. We were not very close with this couple above us even though Mutti talked to her maybe once a week in the hall way exchanging gossip. Her husband played cello in the town’s orchestra. The only stress we had was when he had to rehearse for one of his next concerts – which wasn’t seldom.

Above them on the second floor, under the roof so to speak lived an older couple in their sixties and we liked them very much. We called them Aunt Rosa and Uncle Walter. They had a garden adjacent to ours with a few chickens and sometimes we were gifted with fresh eggs. Those were rare at this time, rare as chocolate, bananas, oranges, vegetables, butter and almost every kind of meat.

Except for horse meat. I remember times when I went shopping with Mutti – that’s what we called my mother; she very much likes this nickname and even to this day would never accept being called Mother. Sometimes we teased her about that. We stood for hours in long rows with other patiently waiting customers to get any of those groceries. If you had tough luck, you were next in line but the special food or vegetable were just sold out.

Connections to the West, to relatives sending packages of goodies or medical supplies, were worth gold at this time. Unfortunately, the officials from customs and border control always slit the packages open, took what they needed and we got the rest. Our grandparents and other relatives all lived in West Germany; they left East Germany right after the war under very adventurous and dangerous circumstances. People left during the night, approaching the West German borderline where – hopefully – no border police was present, and escaped.

We stayed for a good reason: building up a new country after the war. East Germany needed a lot of officers and policemen and all kinds of educated and willing-to-work people. The police advertised heavily for getting their troops together. My father – we called him Papa – applied for such a job and was recruited as a police officer. That was in 1947. He later became the chief of the town’s police department for criminal investigations. The rank was comparable to a Lieutenant. This is, by the way, why our family had one of the very few telephones in the town.

Our house on the right with the number 4 was followed by five others. The mayor of the town lived next to us in number 6. On the left side of the street, the first house with the number 1 was a villa serving as a home for small children and infants. You would probably call it a daycare today or simply a Kindergarten. Next to it stood another wonderful old villa in which two of our school friends lived. Both villas had great acre-sized grounds with lots of fruit trees. Adjacent was a flower field and a green house belonging to a nursery. It was followed by two more single homes. Of course, all were built in brick and with three stories like ours. In most of the houses lived one or two families.

Our street was not paved; it was covered with a mixture of gravel and sand and certainly had some little holes. Nevertheless, we had sidewalks. The street ended after six hundred meters at a small crossing opening the view into a wide valley of corn, vegetable and potato fields. We enjoyed this wonderful scenery not blocked for kilometers by any building. In the far distance, you could see the vague silhouettes of two villages. One was called Jecha. Especially in summertime, when the sun shone over the fields and some big cumulus clouds moved their shadows over, it was a gorgeous sight.

Turning right from there, you would reach the forest within three hundred meters after passing a big row of hedges and a meadow. This was simply a dirt road. We did a lot of sledding and skiing on this meadow, Papa, Roland and I. The meadow was steep enough and therefore also fast enough for our age. Not seldom did we crash and tumble down with our sled or on our skis. Once my brother and I even broke our sled crashing at the end of a furious fast run hitting a hole in the icy ground and ending up in the fence of the nearby field.

Straight ahead from the little crossing, the gravel road continued winding down alongside one of the big potato fields. With the trees on each side, it appeared like an alley. In autumn, when the fields were harvested it was permitted to collect the left-over potatoes or other vegetables on the fields. We did this every year whenever possible. I am sure it was not to save money; it was just that we had a hard time getting potatoes or vegetables. But it was fun! Sometimes, we did it also before the harvest; this was definitely dangerous. If anybody had noticed , we could pay a high price for doing it. Mutti took some risks here to feed the family with more than just bread and a watery soup.

Turning to the left, our street became a paved road, a little street leading back to town passing over a steel bridge with a single rail road underneath. I will never forget the feeling of walking over this little bridge when a train, pulled by those old steam locomotives passed at the same time: the steam from the locomotive covered us in a big white cloud. Unfortunately, the black exhaust also left its mark, which Mutti did not like too much. When the cloud vanished, you saw the road continuing; houses on the left side and a long four meters high dark-red brick wall appearing on the right. One followed the direction of the railway on the right, one the street almost like a prison wall. They were hiding the large Soviet Army barracks. About 300 soldiers were stationed here. To our knowledge, the wall had only one opening about 200 meters further down the road: the big iron gate with one or two soldiers guarding it. The gate was recessed from the street by about 10 meters opening a little place in front of it as an entrance way into the army grounds.

The soldiers were dressed in their typical dark green uniforms with boots and their unique way of having their belts over their uniform jackets. This made the short jackets sticking out almost like a short skirt just covering the waist. Of course, they carried machine guns, Kalashnikovs, named after the famous Russian soldier who invented them. They had to open the gate manually when some of their trucks or other military vehicles either left or entered the barracks. It was rather seldom that the heavy tanks rolled out into the small streets of Sondershausen: rolling down the streets with their metallic tracks clanking and leaving marks in the concrete. The gate was always brightly lit up after dusk with four heavy beaming lamps.

On the right side of the gate, in the corner of the recessed wall, they had built a concrete pedestal of about 100 square meters, about 2 meters high. On it stood a majestic military-green colored tank. It was a T34, one of the Soviet’s Second World War models that were built during the war in the Ural mountain plants. Even weighing some 30 metric tons it was still a very fast and maneuverable tank they say. It had a 76.2 mm or 3 inch cannon mounted on the turret and a 7.62 mm or 0.3 inch machine gun sticking out of one of the two front hatches. For us, the tank was not only an impressive site but also a symbol for the presence of “our friends” and the German’s defeat in the Second World War.

I have passed this tank many times on my way to or from school or to town. It was still standing there until a few years ago.

2.

School was very influential and beneficial. That was not only in a political sense but also when it came to learning skills for daily life or in the sense of general education. The pure amount of studies we did for our age was amazing. I would find this out at a later stage in my life. The time we spent with the teachers and other authorities also aimed to educate us in the right political way. Being educated about the upcoming German Democratic Republic, its goals and fundamentals, was meant to lead to an understanding that GDR was the supposedly better part of the two German states. The government and its politics were always present: in school, at work or in your leisure time, even in your very private home.

It was very common and necessary to spend a lot of time with “the system”. I remember that we started the day in school with a pledge to the flag of the Pioneers, the political, very influential youth organization in the GDR. We had the picture of the President of the time – Wilhelm Pieck – in our class room. We were called “Pioneers” and wore white shirts with the symbol of the organization as well as blue scarves around our shirt collars, tied in a special knot. The whole movement can be compared a bit with that of the boy and girl scouts. Of course, there was always the influence of the socialistic party SED and the government, or should I say the Soviets? Boys and girls were members of the youth organization. It was very well organized with special events and excursions usually held once a week in the afternoon. We did sports, visited sites, monuments or memorials, industrial companies, production plants etc. We also did long hikes through forests and fields and learned a lot about nature and the local environment. Some of the highlights were certainly visiting and being with the Soviet Army, at least for the boys – probably not so much for the girls.

I remember this special morning in school when we discussed the next Pioneer session. It must have been two months before the big summer vacation of around seven weeks; the school year finished in mid-July and started again on September 1st. Our school was about two kilometers away from home and we walked back and forth every day, winter and summer, storm and rain. We did not have bicycles; those were also rare at that time. And if one was available, the parents used it for getting to work or to do errands. We had to walk down the Possenweg about three hundred meters and then zigzag through some small streets. We then passed a Soviet military graveyard adjacent to the school building. It had a big monolith standing in the middle with a large red Soviet star on it. It was surrounded by a little park in which some tall oak trees made it a rather quiet place. We had to pass through it to get to the massive wooden entrance doors of our school. The school was named Käthe Kollwitz Middle School. In short, she was one of the opponents of the National Socialist movement and also close to the leftist parties in Germany during and after the First World War. She was also famous for being an artist and sculptor.

Our school was a big, L-shaped sandstone building formed and was four stories high with angled tile roofs. Inside the L-shape was the school yard. There were also two doors into this yard that we used during our lesson breaks. Our class teacher was Frau Rosenstiel, the wife of the school’s director. She was a very good teacher and we all liked her. We had most of our lessons with her: German reading and writing, math, grammar, sports and music. I still have my certificates signed by her with my grades. I was a year older than most of my classmates as I was a bit sickly when I was five and six years old. My parents decided not to let me start school until later.

This Thursday morning, Frau Rosenstiel had invited the leader of the local Pioneer organization. He was in his thirties; I cannot recall his name. After giving us a short rundown of possible future events and plans, he continued with what was very exciting news: “My dear young pioneers, I have planned a very special event with our friends from the Soviet army. I am very pleased to tell you that we will spend an afternoon with the soldiers out in the field. They will not only show us their maneuver field and heavy equipment but also let us ride with their tanks.” First it was quiet, and then a little storm of cheers came from the class, mainly from the boys I should say. This was really exceptional good news and we could not stop talking about it for the next three weeks. It was spring after all, May to be exact, and it would be a good time for such an adventure. It was hard to believe this would be happening to us.

Later in the day, my brother Roland told me that some of the older pupils were also invited. I could not wait. We told Papa and Mutti about it as we always told them everything that happened in school. They did not seem to like it as much as we did but I thought that it was just because parents worry all the time about their children. Sooner or later, I would understand them and their reservations. The days went by but we never stopped thinking about it and imagining what it would be like to ride in one of those metal monsters.

3.

It was sunny with a totally blue sky and the temperature was around 25 degrees. Weather you would expect for the month of June. But as we all know it is not necessarily given to have such weather at this time of the year. We were lucky. A real gorgeous day for our event. We had a bit of a wind going which caused a few little dust clouds here and there.

It was Wednesday and we were still in school; this was the big day! It was early afternoon. Lunch was served in school and then we finally gathered in the school yard in a formation similar to soldiers starting to march. Our youth leader gave us a short explanation of what our schedule was and of what would happen this afternoon. We then walked in formation out of the school yard around the school building following the street to the right using the sidewalks. I have to say that very few girls were coming with us, no surprise. Girls have other interests!

It took us only ten minutes to reach the big iron gate in front of the barracks as the street leading to them was just four hundred meters from the school. There we stood, in front of the gate. Some formalities with the guards were discussed; some of the soldiers were somewhat fluent in German, so there was not really a problem in communicating. And of course, they expected us!

We were permitted to walk through the gate. It wasn’t the first time that we were inside the barracks. Every year, there was an open day and all people could visit the barracks and see all the amenities and special displays they had prepared for the visitors. Everyone was served a bowl of soup from one of the mobile kitchens we called “Gulasch-Kanone”. Literally translated something like a “beef stew canon”.

We marched on over the big square yard surrounded by three story high barracks to one of the huge garages. In front of them, several of the open army trucks were parked side by side. The trucks had a front cabin for three soldiers, the driver and two others. In the back, there was a framework of steel tubes combined with wooden planks for loading any kind of material and/or just two rows with wooden benches to carry troops. Army trucks are really not comfortable in any sense. Sitting on those hard wooden benches is not a pleasant way to ride.

I looked around and saw my brother Roland a few meters away. I could see the excitement in his face and he could not wait to go out to the maneuver fields and get into the tank. The boys were all in shorts with the blue scarves around their necks and mostly short sleeve white shirts. The few girls attending were in summer dresses also with the blue scarves around their necks; I wasn’t really sure how appropriate their dresses were for the afternoon. Maybe they were just interested in seeing the tanks and watching how the boys were having fun.

One of the girls was Roland’s classmate and her name was Bärbel. She was the daughter of the mayor; as I mentioned she lived next to us in number six. I think that Roland liked her a lot and even years later, he still kept her in his memory and even had some brief contact with her. She was pretty with blond hair, big blue eyes and tall; she was also wearing a dress.

We were to board the trucks; we were not tall and certainly needed help from the soldiers as well as from our leader to climb on the platform in the back. I think that we had all in all three trucks with some 16 seats each. Sometimes the wind blew and the boys were laughing as the girl’s dresses revealed a bit more than they would have liked entering the trucks.

After sitting down, we were instructed to firmly hold on to the metal bars that usually held the fabric covers in place. We did not need the covers today but we surely needed to hold on tight! We were going for a ride – and what a ride this was!

The fields and maneuver sites were a few kilometers away. They used old dirty and bumpy fields that were not nice and flat for a reason. Ups and downs, steep ramps and hills, flat sections, big holes and hillsides of all kind of grades and angles. Test grounds built by Mother Nature more or less and worsened by the army exercises. There were also some bunkers and trenches to give the proper environment for the soldiers playing war.

Riding to these areas on the Spartan military trucks was an adventure in itself. We were almost flying from the bumps in the road: lifting us up and at the next moment making us land hard on the benches. I heard some girls screaming – and also some boys. I am sure that everybody counted their bruises that evening and the next morning. I was one of them. I guess that we were excited enough to stand the pain but were also glad when the trucks entered the field where they came to an abrupt stop. Dust clouds were all over us and covering the scenery. Did it really matter? No, it didn’t.

I forgot to mention that the Russian soldiers accompanying us were unfortunately not very proficient in German to say the least; our Pioneer leader spoke a bit of Russian, which helped us with the most important communication. Russian was the first foreign language we could learn in school, starting in third grade. To advance and learn English, you needed a very good grade in Russian first. But learning English was also seen as not appropriate: after all, English represented to a certain degree the Western capitalist culture.

We left the truck one by one with a little help from the soldiers. Our clothes showed that it was literally a dirty ride. Mutti would have to wash them. Without having a washing machine like in the West, this was hard work for her. God bless her! Of course, we did not realize it and took it for granted having clean clothes whenever we needed them.

We looked around and realized that there was not a single tank to be seen. No noise to be heard which would indicate such a monster coming around the corner or appearing anywhere from behind on one of the hills. Also none in front of us or on the steep ramp-like track on the right a few hundred meters distant. But we noticed tracks and the profiles of the big chains left in the dirt everywhere. We must be in the right place!

We walked around and checked out our environment a bit; every step we made on this dusty ground left a small sandy cloud and soon our shoes and socks were covered. In spite of the open field we stood on, not all parts of the maneuver field could be seen. Also, on the right, maybe 200 meters away, a few rows of trees and bushes blocked the view. In the distance was Sondershausen on a bit higher ground than we were. In front of us, the moon-like terrain, was probably at least a few square kilometers in size if not bigger.

I walked to my brother Roland and asked him: “When do you think the tanks are coming?” He was my big brother and I always looked up to him. He shrugged his shoulders and responded simply: ”I do not know but I hope they come soon” expressing that he was at least as anxious as I was.

First, I thought that a bee was buzzing around my head; then I realized that the noise I heard was too much of a rumble to come from bees. The ever increasing sound of powerful diesel engines combined with the squeaky rattle of heavy metal tracks. The tanks were on their way! We could not see them yet but our adrenalin level rose by the second. Our hearts beat faster and everybody tried to get the first glimpse. The air was vibrating.

Suddenly, at the end of the little forest, one of the tanks appeared; first just the long canon mounted to the turret, then the front constructed with massive steel plates. Seconds later, the full length of a tank could be seen. We watched the left side with the wheels and its track rattling over them. The tank left quite a dust cloud behind it. Coming closer, I saw more and more details like the driver’s open hatch, the machine gun sticking out next to him in the front, the metal boxes for tools and supplies on top behind the tank turret. And of course, there was the commander looking out of the open hatch on top of the turret. They came straight toward us at quite a speed. My guess is that they were doing 50 kilometers an hour.

The tank was bouncing a bit coming over some of the bumps and driving through the holes in the ground. It did not have any problem coming down the ramp. We had to cover our ears now as the noise got very loud. In the same moment, a second tank curved around the edge of the forest and approached us no less intimidating or less impressive than the first one. We jumped aside making space for the arrival of the armored vehicles. One of the Russian soldiers waved his arms indicating to the commander where he should stop. Just a few feet in front of us, the first T34 stopped with a loud squeak; the engine was still roaring. Now the second tank came close and made a little turn by stopping the left track for two seconds. This way, it came alongside the other one and stopped ten meters away from it. All this caused more dust flying around and I heard some coughing. Some commands were shouted and finally the engines stopped.

We were in awe. Standing right in front of us were two of these massive war tanks we heard so much about: 30 tons of steel armor with a cannon so big that I could probably put my arm in it and a machine gun that could fire massive amounts of bullets in the air. The tracks were at least a meter wide and must have weighed tons themselves. The turrets were turned straight ahead now pointing in our direction. We could see the head of the pilot through the open hatch in the front.

The first commander climbed out of his hatch on top and jumped on the wheel cover and then down to the ground. He walked to the soldiers and started discussing what we thought were the next steps of our adventurous afternoon. Meanwhile, the second commander disappeared inside his tank. We looked at our Pioneer leader, obviously with very questioning expressions in our faces, because he answered before we could formulate our question:

“As far as I understand the procedure, we will embark a maximum of four of you in one tank. One will sit down in the front below and beside the driver; one will sit in the commander’s chair right below the turret hatch. Another one will stand up in the turret with the commander; eventually we have two of you there. There is not too much space inside the tank. You should tell me now who wants to really ride and who does not. Maybe the ones who do not want to ride step back so we can see how many trips we have to make.”

We looked at each other and moved forward, not all of us. I guess that the fearful appearance of these tanks left marks in some minds. Surprisingly, two of the girls wanted the ride. From the boys, more than two thirds wanted to do it. That meant that we had four trips to make with the two tanks. We had time enough and of course none of us cared how late it would get this afternoon. Our leader came to the same conclusion; he scheduled about 20 to 30 minutes for each ride. We got into groups of four and could not wait to climb on and into the tanks.

Roland and I were in the same group with two other boys. It would be extra special to ride with my brother, I knew that. We did a lot of things together with our friends from school or from the neighborhood. Most of the kids in our street went to the same school. We knew each other for years and spent hours together playing. Vacation time was very exciting and our rural environment with forests, meadows and fields encouraged us to play all kinds of common games and activities.

The first two groups climbed into the tanks. The smaller kids needed help to get up and in and were instructed where to sit or stand. I saw only one boy standing up in each of the turrets, so there must have been an additional seat of some kind inside. What did I know? It did not matter anyway to me. I would soon see for myself. I felt the excitement rising. Another half hour and we would climb on the tank. Where would I sit? Inside? Standing up? Or maybe beside the driver down below in the front?

My thoughts were suddenly interrupted when the engines started roaring through my brain. Thick clouds of black exhaust fumes were spewed from the two pipes in the back. We automatically jumped aside leaving enough room for the tanks to roll out of our place. The first turned right by stopping the right track from rotating and just moving the left track with the typical squeaking noise from metal grinding on metal. Amazing how easy it seemed to steer this T34 around. It made a half turn, slowly and almost carefully until it headed away from us.

We could now see the back of it. The engine was located in the back under a metal grid obviously providing some cooling. On top of the chassis on the right was a cylindrical metal container, on the left a rectangular toolbox. Also, strapped with leather bands to the back of the turret there was a camouflage net. On the angled back metal plate, two other cylindrical cans were mounted, one left, one right. In the middle of the plate, the two exhaust pipes exited the chassis. All over the sides and on the turret were finger-thick metal bars to hold on or helping to mount the tank. Those especially helped us kids to climb on and inside the tank.

The driver stepped on the gas pedal; in fact, there wasn’t any as I found out later. He had some levers to steer and also to accelerate the tank. We had to stick our fingers in our ears. The roaring was overwhelmingly loud. The tank drove away hitting the first bumpy holes and leaving a cloud of dust behind. Now the second one turned by not only stopping one track but also slightly reversing it. Then it also pulled away following the other. We watched them going around in circles, putting on some impressive speed, going up a hill and diving down into some sunken valleys always leaving clouds of dust behind them. At one time, the second tank almost jumped a bit by driving over a big bump of dirt leaving the front half in the air for a second or two. I still regret the fact that nobody took any pictures that afternoon. Nothing left besides good memories.

The tanks came back in the same impressive way they had arrived. It was our turn now to experience such a ride! The tanks were located side by side and after the others had disembarked, we were to mount it and take our places. Roland went first, of course. He had the luck and sat right next to the driver. During the war, this was the place for the soldier operating the front machine gun. There were two other seats inside: one a bit behind the driver and one just underneath the turret. This was the one I sat on. It was a half-bowl shaped metal seat and I remember that I could not reach the ground with my feet. It felt okay at first. I saw Roland down below trying to communicate with the driver. I looked around and saw some more equipment that had purposes I did not understand. There must have been also cases of ammunition and tools. And there was also radar communication equipment. Its antenna was on top of the turret. During the Second World War, the T34 had a crew of four soldiers which included the commander, the driver, the machine gun operator and the radar communicator.

The top hatch stayed open during our ride. We started, and as I was not standing up. I could only see through the front hatch. Only when the tank was on an upward move, I had a view. The bouncing over the terrain was so bad on my behind and my legs that it really hurt. No padding on the seat and hardly what you would call a suspension. Oh well, it was fun. We did some turns, some runs up and downhill and some little diving exercise like the others did. At one point, we stopped. I tried to figure out what was going on in the darker front below me. Roland and the driving soldier where pointing back and forth and were somehow communicating. Roland knew a few words of Russian, not sure if that helped him here. Nevertheless, I saw him holding the one lever and pulling it. The tank pulled forward for maybe a hundred feet and stopped again. Later, he told me that he drove the tank. Not very far but at least he did.

Our ride ended and we jumped out of the tank with help from the soldiers. My knees and legs were a bit weak and my butt hurt, but who cared. We went to the others and exchanged our experiences. Roland proudly told us about him driving the tank. The other kids had visited some of the trenches and maneuver sites, the underground and earth-built bunkers; certainly interesting to see how soldiers lived during maneuvers but no comparison to our adventurous ride in the tanks. Decades after that afternoon, Roland and I still talk about the event. In fact, it’s now possible to even own one of those tanks – you can simply buy them.

4.

At this time, Mutti was in her early thirties, Papa in his late thirties. Papa was the chief crime investigator in the town. The position was important for the obvious reasons but also in a political sense. In such a position you had to be a member of the SED – and Mutti too. You also had to be politically “clean” in the sense of supporting the regime in all aspects of your public and private life. This included no or almost no contacts to the West. No Western radio, news or newspapers, no contact with Western individuals, even relatives. The authorities did not like it but had to realize that family contact with relatives in West Germany could not be totally avoided. If they got even the slightest information about such contacts, you had to report it. You were then investigated and pressured to stop. Being reprimanded once would lead to ongoing observation and investigation about your entire family and its activities and behavior. Those investigations were handled exclusively by the Stasi, the State Security Service or “Staatssicherheitsdienst”. It was comparable to an organization like the CIA, of course with different directives and principles.

It was a Tuesday afternoon. Roland and I came home from school almost at the same time. Mutti had gotten a package from my grandma in Nuremberg. She was Papa’s mother and lived with Papa’s brother and sister-in-law. It was always a highlight when we got a package from West Germany. What was even better this time, it was not opened by the border controls or penetrated with holes from the sticks they put through; it was their way of testing the content. It was entirely untouched. It was quite large, maybe 30 by 40 by 60 centimeters. Mutti opened it and Roland and I watched her impatiently. Why? We could expect that there was chocolate in it, and other goodies we could seldom enjoy simply because they were not available or if we could get them, they tasted horrible. The same applied to fruits like bananas and oranges; you just could not buy them.

We had a large kitchen for a small apartment of 75 square meters; a big double ceramic sink, a kitchen cupboard, a wood-fired oven and a little pantry. For making warm water, we had a gas boiler you had to light to get hot water. I remember that my grandma from Nuremberg visited us once. She had to light the gas boiler but forgot the matches. Well, when she got back to light the flame, a lot of gas had filled the room and we just heard a big explosion. Grandma was fine but she never lit the flame again – and we would not let her anyway.

Mutti got the scissors out, laid the package on our kitchen table and opened it. This compared with Christmas or Easter or birthdays: you just cannot wait to open your presents! The package was really untouched and we could not wait to see what was inside. After removing the first layer of paper, we saw two chocolate bars, a few pieces of chewing gum, three oranges and some kind of medicine. Not sure what it was or what the purpose of it was. We were not sick recently. It was not seldom that we asked for medicine supply from the West as there was very little available here. Especially when it came to special diseases, we had to rely on getting it from our relatives. Mutti did not seem to be surprised, she must have asked for it.

I remember that I had scarlet fever when I was five years old; Mutti went to our house doctor who practiced in a big old white villa at the end of a long street with the name Karl-Marx-Alley. His name was Dr. Dönitz. We liked him, he was very helpful and a good doctor. Whenever we were sick with more than just a cold, Mutti went to him. In fact, I was very sick several times in my younger days with scarlet fever and measles and other stuff. It was just a nightmare to get the medicine to cure us. Quite often the only answer you heard was: “I cannot help you as we do not have the dedicated medicine, Mrs. Mann. You better have some relatives in the West. Tell them what you need, I will write it down for you.” Mutti then wrote a letter which took a week or longer and then our relatives would send the medicine to us which again took one or two weeks to arrive. And hopefully it went through the customs.

After we removed the goodies, we discovered some fabric. Looking closer at it, these were pants! Three pairs, one was larger for Papa and two were of smaller size for Roland and me. They were dark green and of Corduroy style. We called them Manchester style pants with regard to the British well-known textile city; Manchester was the European textile center.

We pulled them out and looked at them. They had a belt and two pockets in the front and also cuffs. They looked very classy and would be certainly eye-catchers when worn in public. We liked them and put them on right away. Looking like studs we walked around in the apartment and showed Mutti. She was happy for us; actually, she was and is always happy when good things happen to her children. She is just what you expect and imagine from a fabulous Mom. We were anxious to wear them on our next Sunday walk to town. We were absolutely sure that Papa would feel the same way.

At the bottom of the package was a letter from grandma giving us greetings, wishing us well and hoping that the pants would fit and that we’d like them. No problem there, we really did. Mutti gave us a piece of chocolate and saved the rest; we probably would have eaten it all at once otherwise. She also put the oranges away and kept the medicine.

We changed out of our new pants and into our playing outfits and went outside. It was a beautiful Tuesday afternoon and our neighbor kids were already outside having fun. Mutti’s rule was that every afternoon when the church bell struck six times, we had to come home. Mutti insisted on that. We did not like it very much, especially in summer when it was still light and the sun had not gone down yet. Also, the other kids’ moms seemed to be a bit more tolerant in this regard.

As usual, today we did what we were supposed to do. Just as we turned into our little street, we heard a car coming up from the town. The two-cycle engine made a hell of a rattling noise leaving a cloud of white steam behind. It was a green car, a police car. They were of the military style, a bit like a jeep but not as strong in design and appearance. They called it a “Kübel”. The car turned into our street and we knew instantly that Papa came home from work. He was seldom that early but this had to do with his job. Many surprising things were happening in our town and in the county. He was called sometimes in the middle of the night and they picked him up to go to a crime scene. Other times, he did not come home for the whole night and we did not see him for two or three days. Papa did not drive the car himself; he always had a chauffeur who brought him and picked him up from home or from work.

The car stopped in front of our house and Papa stepped out. We ran to him and greeted him. Mutti also must have heard the car and stood on top of the stone stairway leading up to the door of the house. We went up the stairs and Mutti sent us first to clean ourselves up while she gave Papa a kiss. There was a special glow around Mutti. Maybe it was because of the nice package we got from Papa’s mom today. After he put down his briefcase and put on his house shoes, Mutti showed him the gifts we got and also his new pants. He liked them, too. Still, he wasn’t as excited as we were about them.

I wondered why.

5.

The reason why Papa came home early that day was simple. Usually, he worked long hours or had to go to crime scenes in the evening or simply had meetings. But today, Mutti and Papa had to go to the party meeting of the SED in the evening. They were never really comfortable with attending the meeting nor did they agree with the government of East Germany and its communist-style regime. The government called it a socialist republic while in reality it was more a dictatorship ruled by the SED with the help and support of the Soviets. The political pressure on everybody was enormous and especially on two adults being well-known in the community like our parents.

My parents stayed in Thuringia after they had to leave their homeland in the latter days of the Second World War; they were from the Sudetenland, a small region of northern Czechoslovakia. Today this country is divided in two autonomous, independent countries.

The Sudetenland was well developed by the Germans who had settled there. Reichenberg was probably the richest town with a lot of textile industry. My great grandparents had a few factories there. Ever heard of somebody with the name Ferdinand Porsche? The guy who built the first beetle bug for Hitler? Which became a Volkswagen! That’s him; he was born in the area. He later founded the Porsche factory and built the famous sports car.

To cut history a bit short here: After the war was lost, they were pushed out with nothing but the clothes they wore. This is certainly one of the very tragic parts of German history. All our relatives left with Mutti and Papa and ended up in Thuringia, one of the states that belonged to what was Middle Germany during the war and became East Germany after the Soviets took control.

My parents decided not to go to West Germany at this time and tried to settle and find a new home and work. Papa went to the police and was helped finding a little apartment for them. Nevertheless, my parents were always opponents of the regime and its politics. They always felt that the practiced socialism was really communism in a different outfit. Freedom in speech and free will were suppressed. We were never permitted to listen to any Western radio stations, nor read any Western “propaganda material”, at least that’s what the authorities called all Western literature. You could not criticize the government or say anything critical about the living conditions or the lack of food or failures of the authorities. The slightest remark could lead to at least a serious hearing, if not to temporary imprisonment.

Mutti and Papa had to be very careful saying or discussing anything critical in front of us children or even in front of friends. Friends were very hard to find and everyone was very careful in talking about the government, politics or actual living conditions in a critical way. Any small piece of information could easily be revealed to people who would use it to your disadvantage, maybe just to get ahead in the system. Or they just did not like you. You always had to be extra cautious in public.

Due to shortages in groceries and food supplies, it happened quite often that Mutti and I had to stand in line to get butter, eggs, vegetables, meat or almost anything, even the famous Sauerkraut. Supply was low for many things, especially when you lived in a small town like Sondershausen. Important cities like East Berlin or Leipzig were better off as the government wanted to show the Western world how well their new state provided for its inhabitants. In fact, the rules and instructions were made by the Soviets; they decided where the goods would end up.

Once we were waiting at a grocery store downtown as we had heard that eggs and butter were available. Butter was a restricted product and you had special food stamps for it. We got dressed quickly and hurried down the long street toward town. Some people knew about special supplies and told their neighbors and friends about it so they could go too and take advantage of the situation. Quite often you ended up not getting anything as it was sold out already before you could even get close to the shop. It was very disappointing when this happened and people got angry. Waiting an hour in line and not getting what you came for was sometimes indescribably hard. You got very frustrated and some people just could not keep their mouths shut.

As we finally arrived at the grocery store, people said that eggs just arrived and supposedly bananas too. There was already a long row of mothers with kids and housewives looking for the extra special offer and probably making out a special dish in their mind for the evening. You stood there quietly and hoped that you would be one of the lucky ones. Mutti always reminded us to be quiet and to not say anything, just to wait patiently. I could not see too much of what was going on in the front of the line; I only noticed that we moved slowly forward. Mutti always checked the people around her; she was very cautious and observant. Maybe being married to a policeman created the extra awareness in her. Especially when men were waiting in line – that caught her immediate attention. I followed her view as well as I could and noticed the man three places in front of us. He was about six feet tall and dressed in a white shirt, brown jacket and black pants. He wasn’t really someone that would catch anyone’s attention. Just a man who wanted the same things we were waiting for, bananas or eggs or, even better, both.

The line got shorter, pretty soon we would have the pleasure of getting at least some eggs for dinner. Bananas were usually the first to go. Some people had chickens and therefore had fresh eggs of their own. Mutti always made soft eggs for us, boiled a few minutes in water. We always loved to hit the eggshells and open the egg with a spoon. Eating it with a grain of salt and a slice of bread with butter was a real treat. My mouth was watering.

I heard some women talking; a few words went back and forth. Suddenly, it got loud. Something must have happened. I wanted to leave the row but Mutti held my hand strongly in hers and kept me beside her. There was some movement in the front and the only thing I could see was that a few people pushed hard against the shop door. “I have been waiting here now for over an hour”, a woman screamed. “I want my eggs!”

“Are there any bananas left?” another woman shouted at the shop personnel. “We have the right to get some. Why don’t you have enough? It is probably all in Berlin! ” Others were still and did not say anything, distraught and disappointed that their effort went wasted. It seemed that the last eggs and bananas were sold. While some women had already left, the man in the brown jacket stepped forward and addressed the woman who made the comment about the bananas being in Berlin in a very serious tone: “Please come with me to the office!” The woman was stunned and fear covered her face immediately. She did not respond but quietly followed the man.

The man was from the secret service, the Stasi. They did not like the criticism.

6.

Mutti and Papa got dressed; Mutti wore skirts or costumes with blouses most of the time and Papa some slacks, white shirts and usually a jacket. They needed only about three minutes for the 200 meter walk over to the FDGB building just opposite from our street.

The SED meetings started always at eight. All participants were expected to show up on time, or even better, early. Participation was also a must. You really did not want to be on their black list. The authorities and the secret service registered everything about you. They knew your upbringing, your history, your job, your family, hobbies, special behaviors, everything. Especially all information about family in the West, including addresses. If you were not a member of the SED, in their view, you were of lower class and not a contributing member of the society. You were obliged at any time and without any doubt or question to support the regime. Showing the slightest doubt about the power of the government was absolutely not acceptable; it could bring you to court, which in many cases meant prison time. Failures in supporting the government and its authorities were always made public; the secret service would not hesitate to give out the information so it could be presented for example on the party meetings Mutti and Papa went to.

The participants counted about 50 persons of the who’s-who in Sondershausen. Again, you had to be a member of the party – if you were a teacher or officer or held other important positions. The evenings, I was told later, were full of presentations and discussion about politics in general and specifically related to the brains of communism and socialism: Marx, Engels and Lenin. The SED had to make sure that their “flagship” members “sailed” in the right direction so to speak. They had to train you in the doctrines of these men and how they could be of any help in our daily lives.

Mutti and Papa were never happy at those evenings. They had experienced Russians’ cruelty during their escape from Sudetenland and found themselves somehow again right in the middle of their presence and influence, but they had to play the game.

They came home early that evening; I was still awake. We slept in a big room right beside the living room. The pocket door was closed but had a milky glass insert which let some light in from the front room. The room had a wooden parquet floor and was rather spacious, so we could play there when the weather did not allow us to go outside. Our beds stood diagonally opposite from each other in the corners. The room had also two windows that looked onto the garden. It also had a bigger pocket door that led to our parents’ bedroom.

The windows of our bedroom also bring up memories. Santa Claus usually came through them on December 6 and poured his goodies onto the floor. That was after he asked us the question if we were good boys: we always answered – of course – but with a rather quiet and fearful “yes”. The other special memory of the window I have is when Mutti and Papa asked us if we would like to have a little sister. There was for some reason no hesitation in Roland and me agreeing with this thought. This time the answer was loud and clear: “Yes”. We were told that a cube of sugar on the windowsill would help to tell the Stork about our desire and to bring the little sister at a later point in time. That was last year in October: a few days, after the sugar was placed on the windowsill, it had disappeared.