Tony Rinaudo E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: rüffer & rub visionaries

- Sprache: Englisch

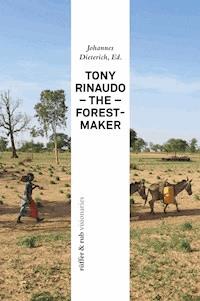

The Australian agronomist Tony Rinaudo revolutionized reforestation in Africa with Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR). His method is based on deploying tree stumps and roots that still grow even in degraded landscapes: thanks to the protection and care of the shoots, the original tree population can be regenerated without major financial costs. The method is now successfully applied in at least 24 African countries. Where the desert was still expanding 20 years ago, farmers reforest large areas with FMNR: in Niger alone seven million hectares of land were already restored in this way. Up to 700 million people will possibly be obliged to leave their homelands during the next three decades because of increasing desertification in the landscapes where they live. In the opinion of scientists, there is only one hope: to convince the local farmers of 'sustainable land management'. Tony Rinaudo believes that with FMNR he has found the appropriate method for such management - and just in time to stop, or even to be able to reverse the destruction of livelihoods.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 180

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Translations from German (texts by Johannes Dieterich and Günter Nooke, and appendix) and proofreading by Suzanne Kirkbright.

Table of Contents

Preface |

Anne Rüffer

Prologue |

Johannes Dieterich

Tony’s Travails |

Johannes Dieterich

Discovering the Underground Forest |

Tony Rinaudo

FMNR is Now a Widely Scaled-Up Agricultural Practice in the Drylands: A Robust Legacy of Tony Rinaudo’s Career |

Dennis Garrity

“Trust Would Be a Good Starting Point” |

Interview with Günter Nooke

Postscript |

Tony Rinaudo

Appendix

Bibliography

List of Photos and Diagrams

About the Authors

Preface

Anne Rüffer, publisher

December 2, 2015, Geneva. SRO (standing room only) in the city’s Auditorium Ivan Pictet. Thronging it is a group of distinguished persons. They have come to honor the four winners of this year’s Alternative Nobel Prizes. The auditorium’s building bears the name “Maison de la Paix” — “home of peace”. Rarely has the name of the venue for an event so closely accorded with its thrust. The event is kicked off by two speakers: Barbara Hendricks, who is Germany’s minister of the environment, and Michael Møller, who is Director-General at the UN in Geneva. The event’s title is “On the front lines and in the courtrooms: forging human security”.

The discussion following the two speeches is conducted by the four winners. Suddenly, one of them, Dr. Gino Strada, makes a statement of electrifying import. He states: “The UN was founded in the aftermath of the Second World War. Its purpose was and is to liberate following generations from being hostages of unceasing warfare. Since that day, the world has experienced more than 170 armed conflicts. And you have never broached the subject of how to abolish warfare? Come on guys, this is incredible!” The audience responds with embarrassed laughter and incredulous amazement.

Gino Strada knows all too well what he is talking about. In 1994, he founded “Emergency”. This NGO provides medical treatment — often supplied at clinics built by Emergency itself — in regions roiled by conflict, and, as well, development assistance to victims of warfare. Of them, 10% are soldiers themselves — with the remaining 90% being civilians. Strada ends his statement with “You can call me a Utopian if you like. But remember, everything appears to be a Utopia until someone realizes it.”

“I have a dream.” Made by Dr. Martin Luther King, this statement is probably the one the most often quoted over the last few decades. That’s because Dr. King’s dream of a world in which justice prevails is shared by so many people. Some of them — more than we are probably aware of and yet not enough by far — have devoted themselves to employing their guts, their hearts and their minds to making this dream come true. Along with Dr. King and Gino Strada, other well-known “dreamers” include Mother Teresa and Jody Williams. Calling them “Utopians” is actually anything but an insult. Each great advance recorded by humanity started out as a Utopian idea, a hope, a vision.

This book is the second in our new series of “rüffer&rub visionaries”. We have a very clear objective in launching it. These books are going to fan the sparks emanating from the ideas and hopes propagated by these visionaries into bonfires of dedication and endeavor. The heart of each book is the author’s very personal look at her or his — highly-important — scientific, cultural or societal topic.

Each author will tell — in simple, inspiring words — how she or he got involved with this topic, and how she or he started looking for answers to its questions that made sense, for solutions dealing with its problems. These books will tell you what it means to commit yourself to a cause, to live your commitment every day, to develop and implement a vision for its realization. These visions are highly variegated — political, scientific or spiritual — in nature. All of them share their visionaries’ yearning for a better world — and their willingness to put their hearts and souls into realizing them.

All of these visions and all of the activities undertaken to make them come true share something else in common: the deeprooted conviction that we can positively shape our future, that we can restore the health of the planet on which we all live. Another strong conviction adhered to by all of us: we are convinced that each and every one of us is capable of undertaking the steps required to make each of us part of the solution, and not of the problem.

Prologue

Johannes Dieterich

Up to 700 million people could be obliged to leave their homelands during the next three decades because of the rapid pace of desertification in the landscapes where they live. This is no prophecy of doom made by an attention-seeking apocalyptic luminary, but rather the forecast from over a hundred scientists who convened in March 2018 in the Columbian capital Bogotá. In their joint report, experts of the Bonn-based Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) state that by 2050 climate change and land destruction threatens to halve agricultural yields across vast swathes of the world. As a result, we must expect social destabilization and violent conflicts for the growing shortage of natural resources.

Admittedly, the shocking scenario also caught me off guard — even after more than 20 years living in Africa, I was unware of the scale of the desertification of arable and pasture lands on the continent. When I met Tony Rinaudo for the first time in March 2016 it was not because I was chasing apocalyptic scenarios but part of my search for a ‘positive story’ from Africa which my editors in Germany are requesting with growing frequency. In view of the misery in other parts of the world, there is now a greater appetite for encouraging news from the continent once afflicted by diseases, wars and disasters. Rinaudo admirably fulfilled the expectations of him: the forest-maker made his mark as a champion of hope.

One could easily write a heroic tale based on his story: the selfless missionary turned successful campaigner against the desertification of entire landscape. But this would not do him any favours. Instead of being glorified Tony Rinaudo prefers to make himself dispensable. The agronomist believes that his mission will only be fulfilled when his idea has turned into a ‘movement’. And when millions of people are self-motivated to stop cutting down trees on their fields and to get back to an integrated method of farming. That this paradigm change is feasible without massive efforts is the most intriguing aspect of Rinaudo’s discovery. To make the degraded landscapes flourish again requires neither vast sums of money nor undue exertion.

Being on the road with Tony Rinaudo was one of the most impressive experiences of my travels on the continent. I have rarely encountered a pale-faced human being who is so ‘in tune’ with the African population. Arrogance is as alien to him as cynicism—or the patronizing attitude, which is the cardinal sin of so many white expat helpers. Tony suffers just the same as a smallholder farmer whose goat died; and he shares in his joy when his ‘Apple of the Sahel’ tree bears its first fruits. And all this is in ‘Hausa’, the colloquial dialect of West Africa that the Australian speaks like ‘a donkey from Kano’, as his conversational partners complement.

Rinaudo and his method of Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) are the central theme of this book. In the opening report, I describe my journeys with the ‘forest-maker’ to Ethiopia, Somaliland and Niger, where Rinaudo discovered the ‘underground forest’ almost 35 years ago. Rinaudo then gives a personal account of how he developed the FMNR method and demonstrated its benefits to the local farmers. In his contribution, the agronomist Dennis Garrity discusses the scientific facts about FMNR. And finally, Günter Nooke, German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Personal Representative for Africa, talks in an interview about the political ramifications of the forest-maker’s discovery.

According to the scientists gathered in Bogotá, there is only one hope in the light of the rapidly advancing land destruction: namely, that local farmers can be convinced of ‘sustainable land management’. Tony Rinaudo reckons that he has found the appropriate method for this kind of ecological management with FMNR — and just in time to stop the destruction of our livelihood or even being able to reverse it. While the former missionary personally experienced his discovery as a religious revelation, an agnostic is reminded of the saying by the German romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin: ‘But where danger threatens / That which saves from it also grows.’ (‘Wo aber Gefahr ist, wächst das Rettende auch.’)

For updated information about the FMNR method, training and educational films as well as success stories, please visit http://fmnrhub.com.au

–––––––––––––––

Countries mentioned in this book where FMNR is practised.

–––––––––––––––

In 1999, Tony Rinaudo first arrived in Humbo, Ethiopia. Now, this village and neighbouring Sodo are flagship regions for the FMNR method.

In the early 1980 s, Tony Rinaudo’s success story began in the Maradi region. Here, at the heart of a barren desert landscape, he discovered sprouting tree stumps whose root systems could be used to grow new trees.

Tony’s Travails

Johannes Dieterich

The setting could easily be a film location for “Heidi”. A mountain stream burbles along cheerfully. The cows contentedly munch on the lush grass. Resting his chin on his shepherd’s crook, a boy gazes dreamily into the valley. Only his dark skin reveals that this is in fact not Heidi’s homeland. Nearby, two grass-covered huts are the final giveaway that this picturepostcard scene is on a different continent, far away from Switzerland. We are in Africa, or more precisely: we are in the mountains near the southern Ethiopian city of Sodo.

“If you had been here ten years ago, you would have been even more astonished,” says Tony Rinaudo. The Australian agriculture specialist seems ready to burst with joy. When the Melburnian first arrived in Sodo in 2006 the mountains still looked like a natural disaster zone. Instead of the trees and grass the landscape back then was mostly covered with thorny bushes and trailing plants. Erosion had carved deep channels into the slopes. The mudslides regularly raced down the valley during heavy rainfall, even tearing away several African round huts. On one occasion, a family of five was buried under the mud.

In those days, the people in the Sodo region still depended on food aid—like in Humbo, a village situated 50 kilometres further to the south-west whose local mountain resembled the back of a hippopotamus. Tony Rinaudo had been sent at that point to Humbo by the development and relief organization World Vision to support capping one of the last springs that was still flowing. Yet, the expert quickly realized that the local population here had a much more severe problem than the non-enclosed spring: they had destroyed their livelihood by constantly cutting down trees and overgrazing the pastureland.

“We often talked about whether we should move away,” recalls Anato Katmar, whose three hectares of farmland lies at the foot of what was once the hippo’s humpback mountain. “But where to?” Then, he was still living with his wife and their five children in a cramped, small hut. The corn and sorghum harvest yields deteriorated every year and sometimes massive boulders rolled down the bare mountainsides into his fields, burying and crushing the crops. From higher up, the only sound echoing down the mountain slope was that of the surviving animals—the mocking cries of the baboons. The monkeys devoured every piece of vegetation that was still sprouting on the barren slope. On many evenings in the year, the Katmars went to bed hungry.

Ethiopia is considered as the continent’s prime land of famine. At one time, this state on the Horn of Africa—now with a population of over 100 million—recorded the worst drought disasters on the planet.

Until 1984, when Bob Geldof’s “Band Aid” shook the world’s conscience out of its lethargy, half a million Ethiopians had to perish. Even today, like most of the continent’s 55 countries, Ethiopia has difficulty feeding its population. And while the number of those starving has fallen worldwide over the past 25 years, in Africa it has continued to rise: from 181.7 million in 1990 to 232.5 million in 2017.

Besides the political and climatic causes of the chronic crisis, there are also ecological factors contributing—primarily, the soil deterioration and the disappearance of trees. Ethiopia, which was once covered with vast areas of woodland, has lost almost 90% of its woody plants over the past 50 years. Yet, if the experts agree on one thing then it is the importance of trees for the soil quality: they keep the soil fertile and moist, their shade considerably reduces soil temperatures and, as windbreaks, they prevent the desiccated, dust-like earth in the dry season from scattering far and wide.

Ecological devastation has plagued the Sahel region the worst. Until twenty years ago, the desert here was expanding further and further southwards and the trees had vanished. Nearly all attempts to control the growing effects of erosion in the arid zones, by planting new trees, ended in failure: most of the costly seedlings didn’t even survive their first birthday. “Millions of US-dollars were wasted,” says Tony Rinaudo, who previously managed a small reforestation programme in the Sahel region. “The extremely low survival rates of planted trees was a bitter pill to swallow.”

However, now this is history, observes the otherwise remarkably modest Australian. The agronomist from Melbourne believes that he has discovered a substantially more successful method of reforestation and soil revitalization—and one that involves zero costs. Rinaudo has undertaken nothing less than to put a stop to hunger in Africa. His discovery could be more significant for the continent than billions of US-dollars of development aid.

“Get me out of here!”

When the Australian first arrived in Humbo in 1999, he was not greeted like the Messiah. The village residents were not exactly hostile to the overseas agriculturalist, but they were certainly sceptical. They suspected that the pale-faced guest was on a mission to sell their land to investors. Besides, his suggestions sounded ridiculous or even suspicious when he talked about letting trees grow on their valuable fields, keeping starving cattle from the bare slopes for a time, or preventing the charcoal burners from cutting down every last tree. The people preferred to have nothing to do with the curious tree-hugger. Anato Katmar was among the few who were prepared to give the foreigner a chance—possibly because he no longer had anything to lose anyway. “Tony”, says Katmar, “was my last hope.” For his first cooperative, Rinaudo had to make do with a handful of farmers, and besides that they were also exposed to the ridicule and mistrust of their neighbours.

Today, there are seven cooperatives in Humbo with over five thousand members. None of them seems to doubt Tony Rinaudo’s method any more. While in the El Niño year of 2016 the region’s other villages were dependent again on food aid, the cooperatives at the foot of the hippo’s humpback mountain produced food surpluses that are at times sold to the UN’s World Food Programme (WFP) to distribute to those parts of the country in need. The mountain is now covered again with woodland trees that grow above a height of two metres; and the thriving fruit trees on the farms not only give shade and fruit, but occasionally, pruned branches for firewood. Meanwhile, instead of his round hut Anato has managed to afford a real house constructed from bricks and a corrugated iron roof. Apart from the standard corn and sorghum (millet), he also cultivates coffee and bananas, which he sells with the mangos from the garden at the local market. The farmer invested his revenue in his children’s education: his two oldest children have already finished their studies, while the three youngest still attend grammar school. The Katmar family currently enjoys three meals a day. “Hunger,” says Papa Anato, “is now consigned to our memories.”

Tony Rinaudo follows the account of his model farmer with a beaming expression—in Humbo, a dream is being fulfilled for the agronomist. In the early 1980s, Rinaudo was sent to Niger by his organization “Serving in Mission” (SIM). His job there was to stop the advance of the desert by planting new trees. For several years, the Australian behaved like a Don Quixote of the seedlings in his fight against the mills of the sandstorms that were devastating the land. Scarcely 10% of little trees had survived the heat and dust storms after planting, he recalls. If one of the seedlings did survive, it was later eaten by the goats or finally cut down by people for firewood. Finally, Rinaudo might have lost his faith as well as his patience: “Get me out of here!”, he quarrelled like Job with his god.

In the eyes of the former missionary, his story in Maradi continued in a biblical connotation. One day, as Rinaudo stopped to let the air pressure out of the tyres of his off-road vehicle to travel more easily through the loose sand, it was as if the scales fell from his eyes. The green shoots, which were sprouting all around him in the sand, were by no means useless weeds—as he had always assumed beforehand. Rather, on closer inspection he saw that they were trees sprouting from their stumps. However, if these sprouts could grow so vigorously in the sand, an intact root system must be supporting them, concluded Rinaudo. As the same phenomenon could be observed across the region, he could assume that there was a vast network of roots spreading beneath the sand of the Sahel zone: an underground forest with roots resembling the branches of trees stuck into the earth upside down. The significance of this observation was not lost on him. He immediately realized that this vast root system made the need for ineffectual tree planting redundant. The underground forest was the key to success.

His Damascus road experience turned Rinaudo’s world upside down as well—from its head to its feet, as Karl Marx would have said. If the little green shoots in the sand were given a chance, they would grow into trees of their own accord, he speculated: all that was needed for the regeneration of the devastated landscape was a penknife, which Rinaudo always carries with him and uses to trim back the shoots of the young trees that grow more like bushes. As the sprouting trees can draw on the nutrients that are still stored in the root system, particularly sugar, they usually grow into mature trees at a breathtaking pace. He has often seen how in three years a weak, sprouting stump becomes a five-metre tall tree, explains the Australian.

City of disused petrol stations

Maradi must be the city with the world’s highest number of petrol stations per resident. The filling stations on the arterial routes of the Nigerien provincial city are lined up like telegraph posts. However, most of them are not in use. They exist thanks to a Nigerien governmental ruling which states that only the owners of a petrol station are granted a fuel export licence for the neighbouring country of Nigeria. Obviously, the local border traffic facilitates such high earnings that the costs of building a useless station are very quickly paid off. This is one example of the bizarre bureaucracy which the almost 17 million residents of the West African state must negotiate in their daily life.

Otherwise, Maradi is like any other provincial city in these latitudes: too hot, too dusty and yet full of activity around the clock. The drivers of the ubiquitous motorcycle taxis only spend the fiercest midday heat sprawled across the tank of their Chinese machines, while vintage Peugeot 404s still clatter along the mostly unpaved streets and old men seated on large stones pass the time playing board games. The only lush green in the otherwise sand-coated city is in the stadium with its artificial grass funded by FIFA. Now and then, cattle herders from the surrounding area move in to the seemingly lush pasture with their livestock, city dwellers scornfully report: only to find out that the fresh grass in the football arena is in fact plastic. Otherwise, there is not much for the city residents to laugh about. In Maradi, not even half of those looking for paid work have a job. Most of the almost one million residents must make do with the equivalent of one euro per day. Their corrugated iron huts usually have neither running water nor electricity.