Truly Criminal E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

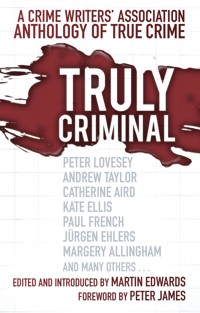

Truly Criminal showcases a group of highly regarded writers who all share a special passion for crime, reflected in this superb collection of essays re-examining some of the most notorious cases from British criminal history. Contributors are all members of the Crime Writers' Association (CWA), including leading novelists Peter Lovesey, Andrew Taylor and Catherine Aird (winner of the 2015 CWA Diamond Dagger). There is also a bonus essay by the late great Margery Allingham about the controversial William Herbert Wallace case, which has only recently been rediscovered. Among the real-life crimes explored in the book are the cases of some of the most infamous killers in British history, including Samuel Herbert Dougal, the Moat Farm murderer; George Joseph Smith, the 'brides in the bath' killer; and Catherine Foster, who murdered her husband with poisoned dumplings. With a foreword by international best-selling author Peter James and updated with a new introduction from Martin Edwards, this collection demonstrates the art of 'true crime' writing at its very best.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 463

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Foreword by

PETER JAMES

Introduction by

MARTIN EDWARDS

The Death of the Sturry Doctor

CATHERINE AIRD

The Compassionate Machine

MARGERY ALLINGHAM

The Stanfield Hall Murders

MARTIN BAGGOLEY

Disappearing Icelanders

QUENTIN BATES

Catherine Foster: A Deadly Dumpling and a Clutch of Dead Hens

KATE CLARKE

Sins of the Father

CAROL ANNE DAVIS

The Cop Killer Who Created Cop Fiction

JIM DOHERTY

Bad Luck and a Blazing Car

MARTIN EDWARDS

The Girl from the Düssel

JÜRGEN EHLERS (translated by Ann-Kathrin Ehlers)

The Aigburth Mystery

KATE ELLIS

Murder in the Shanghai Trenches

PAUL FRENCH

The Queen of Slaughtering Places

PETER GUTTRIDGE

The Headless Corpse

BRIAN INNES

Baby Face

DIANE JANES

A Crime of Consequence

JOAN LOCK

The Tale of Three Tubs: George Joseph Smith and the Brides in the Bath

PETER LOVESEY

The Case of the Greek Gigolo

LINDA STRATMANN

Distressing Circumstances: The Moat Farm Murder of 1899

ANDREW TAYLOR

A Baby Hidden in a Kailyard

MARSALI TAYLOR

The Bite of Truth

STEPHEN WADE

Margaret Catchpole: The Woman, the Legend

MARK MOWER

Copyright

PETER JAMES

Peter’s seven consecutive Sunday Times No. 1 bestselling Roy Grace crime novels are published in thirty-six languages with sales of over fifteen million copies. They have also been No. 1 bestsellers in France, Germany, Spain, Russia, and Canada. His latest novel is ‘Want You Dead’ and he has recently published a volume of short stories, ‘A Twist of the Knife’. He lives in Notting Hill, London and near Brighton in Sussex. He is a past chair of the Crime Writers’ Association and is on the board of International Thriller Writers in the US.

www.peterjames.com

FOREWORD

PETERJAMES

People often say to me, ‘You must have a very warped mind to come up with some of the stuff you write. Where on earth does it all come from?’

‘I don’t think I have a particularly warped mind,’ I reply. ‘I just read a lot of newspapers!’

There are few occasions, I believe, when an author conjures something from his or her imagination that is more bizarre or horrific than a true-life occurrence. That old saw, Truth is stranger than fiction, is one we are all familiar with. It’s an expression we use when we dismiss, with a smile, yet another headline news story, whether in a paper, or on television or on the Internet, that leaves us once more pondering – or reeling – at the discovery of yet another bizarre, hideous or utterly repugnant aspect of human nature. One such example for me – and I think for many of us – was, in recent times, the news story, and footage, about a British soldier savagely attacked and beheaded on a South London street. I’m not sure that anyone would have believed that possible if they’d first read it as fiction.

Whenever I go out with the police in the course of my research for my novels, either here in my native Sussex, or in London, or in the USA, or Germany or anywhere else, I’m constantly reminded just how true that saying is. I remember entering a flat on Brighton seafront where a woman had lain dead for two months, locked in with her cats. They had eaten her face and much of her upper torso. A Johannesburg police officer told me only a few weeks ago of a house burglary during which, for fun, the burglars had poured boiling water down an old lady’s throat. And an LA cop told me of a victim he had attended, who had been involved in drug dealings that had gone wrong, and who had been skinned alive in punishment.

One of the US’s most notorious serial killers had a penchant for disembowelling his victims while they were still alive, and then masturbating in front of them while he watched. Not necessarily the stuff we want to write in books, but sadly stuff that actually happened in true life.

Countless of our greatest crime novels, right back to The Hound of the Baskervilles and beyond that, owe their origins to true stories. Some of these books have been game-changers in the world of crime fiction. That’s certainly true of Truman Capote’s 1966 In Cold Blood, the non-fiction account of a quadruple homicide in Kansas, which became the biggest selling crime book of its time. Thomas Harris’s The Silence of the Lambs in 1988 both changed the rules and raised the bar on crime fiction. The protagonist, Buffalo Bill, who liked to make suits out of human skin, was inspired by Ed Gein, an American bodysnatcher who liked to skin his victims and make artefacts out of it – and their bones.

When I go out with the police, I watch, I listen, I remember. And pretty often I have nightmares. For fiction is fiction, storytelling, mining the deep seams of our imagination and making our readers do the same. But true crime is different, true crime is truly the stuff of nightmares.

I’ve often heard it, from detectives, from lawyers and from forensic psychiatrists, that with few exceptions all murders are committed for one of two reasons: for money or love. I think you will find good examples of both in the pages that follow.

So will you be able to read this marvellously disturbing collection of accounts of very dark deeds, whilst safely tucked up in bed, late in the evening, without suffering nightmares from the contents yourselves? I have my share of nightmares both from what I read and from what I write. I think it is no bad thing that stories like these should shock us. I think it would be far more disturbing, in what they say about us, if they did not.

Peter James

INTRODUCTION

MARTINEDWARDS

Members of the Crime Writers’ Association (CWA) have always been fascinated by real-life criminal cases. A good many of our members specialise in writing ‘true crime’ (this is not a universally popular term, but at least it has the merit that it is generally understood) and the CWA has awarded a Gold Dagger for Non-Fiction since 1978. The Dagger has been won by many accomplished exponents of factual crime writing.

The CWA has, however, only once before published a collection of pieces by members about real life crimes. Blood on My Mind, edited by H.R.F. Keating, and including ten essays, appeared as long ago as 1972. Having edited the CWA’s annual fiction anthology since the mid-1990s, I felt it was high time for us to put together another book of original essays on the theme of, to quote the sub-title of Blood on My Mind, ‘real crimes, some notable and some obscure’.

I was delighted by the response from members, some of whom have not previously contributed to CWA anthologies. Our contributors include several specialists in true crime (although most of them write fiction as well), including Kate Clarke, who with Bernard Taylor was co-author of Murder at the Priory, shortlisted for the CWA Non-Fiction Dagger in 1988. Paul French, who won the Dagger in 2013 with Midnight in Peking, returns to China with his essay. In the spirit of originality that characterises the contributions, Linda Stratmann’s impeccably researched essay includes a special bonus – a highly appropriate recipe for rice pottage, updated from the nineteenth-century original. As she says, arsenic should not be added …

Several leading novelists also made fascinating submissions. They included two CWA Diamond Dagger winners, Peter Lovesey and Andrew Taylor, as well as Catherine Aird and Kate Ellis. The CWA’s membership is increasingly international, and I was pleased to receive contributions from Quentin Bates (a Brit who lives in Iceland), Jürgen Ehlers from Germany, and Jim Doherty from the US.

All but one of the contributions to this book are brand new. This exception is a real find. Thanks to the good offices of Barry Pike and Julia Jones of the Margery Allingham Society, to whom I’m extremely grateful, I have been lucky enough to include an essay by Allingham about the Wallace case that was unpublished during her lifetime, and has previously only appeared in the Society’s journal for members. Margery Allingham was a member of the CWA, and a pleasing connection with her past involvement arose last year when the Society sponsored a national short story prize in tandem with the CWA.

The Wallace case has fascinated writers for over eighty years. Dorothy L. Sayers wrote an excellent study of it, and Raymond Chandler was fascinated by the puzzle. More recently, the late P.D. James published a thoughtful reassessment of the question about whether Wallace murdered his wife. Allingham’s essay makes an interesting companion piece to the extensive literature about the case, though the only thing of which we can be sure is that the debate will continue.

Several other well-known murder cases are considered here. These include a highly original take on the ‘Brides in the Bath’ case, an account of the Maybrick murder (if it was murder), a study of the Moat Farm mystery by a novelist with a distant family connection to it, and an overview of the Rouse case, and its offshoots in fiction and fact. These explorations of famous crimes appear side by side with stories that I am sure will be unfamiliar even to true crime buffs, including a story from Shetland, and a Kentish mystery.

At the outset of this project, I decided that the book would work best if I avoided trying to impose any arbitrary rules or uniformity of approach upon the contributors. Far better that they tell their tales in their own way, sometimes with a personal touch, and at whatever length did justice to their subject matter. To say that I am delighted with the results is an understatement. I like to think that, as a result of the contributors’ diligent research and storytelling expertise, Truly Criminal offers readers a mix of information and entertainment that is rarely matched in anthologies about real life cases.

The very first person to send me a contribution for this book was Brian Innes, once a chart-topping musician with the Temperance Seven, but more recently a stalwart of true crime writing and the CWA, and the long-serving chair of judges for the CWA’s Non-Fiction Dagger. Brian’s enthusiasm for this project prior to his death in July 2014 was typical of the man, and it is sad that he did not live to see it come to fruition. Brian is a real loss to the CWA, and it seems fitting to dedicate this book to his memory.

My thanks go first and foremost to the contributors, Barry Pike and Julia Jones, and to Peter James for his kind foreword. I must also express my thanks to my colleagues on the CWA committee who have given this project their enthusiastic backing, and to Matilda Richards, our editor at The Mystery Press, and everyone else who has worked on this book.

Martin Edwards

Editor, Truly Criminal

CATHERINE AIRD

Catherine is the author of some twenty-seven detective novels and short story collections, most of which feature Detective Inspector C.D. Sloan and his rather less than dynamic assistant, Constable Crosby. Taking an active part in the life of the village in Kent in which she lives, she has edited and published a number of parish histories and several autobiographies for private publication. She was an early winner of the Hertfordshire County Library’s Golden Handcuffs Award and the 2015 CWA Diamond Dagger Winner.

www.catherineaird.com

THEDEATHOFTHESTURRYDOCTOR

CATHERINEAIRD

On the night of Friday, 4th September 1896, Edward Jameson, called doctor, of Sturry, a large agricultural village near Canterbury, left a house in King Street, Fordwich, an adjacent ancient port and the smallest township in England, where he had been having a late supper with his friend Captain Alfred Cotton, at 10.30 p.m. and was not seen alive again.

This case is particularly interesting because of the conspiracy of silence it occasioned. So much so that seventy years later when I was talking about it to an old man who remembered it well and I foolishly got out a pencil and paper, he said, ‘Oh, you mustn’t write anything down. It was all hushed up at the time.’ Quite how right he was – and who it was who hushed it up I didn’t discover until later.

Edward Jameson was one of three sons of Dr William Jameson – no connection with Jameson’s Raid – who had been Sturry’s doctor for the middle years of the nineteenth century. He had died in 1875 at the age of seventy-eight, and, very unusually for those times, left his widow as his sole executrix and legatee – something that I came to see as significant. His three sons were called Edward, John and Willy. John died of cirrhosis of the liver at the age of thirty-three, ten years after his father. Willy, too, died from this condition but much later.

Edward had attempted to follow in his father’s footsteps as a doctor but unfortunately wasn’t clever enough to pass the Conjoint Examination. In those days this did not prevent him from following the calling of doctor’s assistant – one of whose earlier functions, you will remember, was to hold the patient down as a substitute for anaesthesia.

Brother Willy seems to have been much less bright and became a games coach at one of Canterbury’s several public schools. He used to teach the boys to bowl by marking out the field into squares and calling out to them the number of the square to which they were to pitch the ball. He was known to be often short of money and to have rows with his surviving brother over this. There is some suggestion that he was even a sandwich short of a picnic.

Edward Jameson, called doctor, served Sturry as such for twenty years. When his father died, he became assistant first to a Dr Wheeler and then, when he moved away, to Dr T.M. Johnson of Canterbury. When anything beyond his medical capabilities arose, a telegraph message would be sent to Upper Chantry Lane where Dr Johnson lived in a house bombed in 1942. Dr Johnson would then saddle his horse and ride the three miles north out to Sturry. (He probably got there more quickly than by a car in today’s traffic.) Incidentally – but not irrelevantly – Dr Johnson happened to be the Canterbury City Coroner.

Jameson himself had no horse, going everywhere on foot – to Stodmarsh in one direction and to Broad Oak in the other. It may be fairly presumed that he knew the roads of the village like the back of his hand and this is important and you should remember it.

He was a big man, a powerful man with a dimple on his chin and he left a reputation of joviality, cheerfulness and kindness behind him. While he always had a bottle of medicine in one pocket, he inevitably had a bag of sweets in the other and never dispensed the one without the other. He was extremely popular with children and generally of such a well-liked, amiable disposition that the question of suicide was never considered.

He was a strong swimmer and a keen cricketer. The Sturry Cricket Club, which celebrated its centenary in 1963, had him in its team in 1878 when playing Harbledown, which scored 130. Sturry knocked up 209, of which E. Jameson had scored 104 not out for Sturry – the first recorded century for the village team. Dr Jameson bowled between his legs and if it has been reported that I had been seen in Sturry High Street watching a lively demonstration of this by a notably sprightly octogenarian who remembered him well, then I assure you that it was done purely in the interests of research.

The next doctor to come to Sturry was Dr A.H.D. Salt. He was a Parsee and was graphically described to me as a gentleman but not a teetotaller. The year is 1896, the old Queen is on the throne and all’s right with the world – or very nearly. The explorer, Dr Nansen, is on his way to Canterbury to lecture, Mr Weedon Grossmith was there already producing a play, football in the city was at a low ebb, and Kent County Council was bringing in a bye-law that all vehicles were to carry lights at night. Mr Daniel Brice is chair of the Bridge-Blean Rural District Council and is busy writing letters to Kent County Council imploring them not to let the matter of building a bridge at Grove Ferry drop.

They didn’t, but it took them until 1962 to do it …

Dr Jameson is forty-six years old and unmarried. A smart, upright man, he always wore a hat called a ‘Muller-Cut-Down’. (This was a hat half-way between a top hat and a bowler and named after Franz Muller, who was hanged for the killing of Thomas Briggs, the first man to be murdered on the railway in Britain. Muller had altered his black beaver hat by cutting the crown by half and sewing it to the brim.)

And now – as the writers of detective fiction say – we come to the night of … what? Shall we say the night of Dr Jameson’s death?

Friday, 4th September 1896, during which he went about his work, was a fine day until the evening. At ten o’clock that night he walked from his house in Sturry High Street to his friend’s house in Fordwich – about a third of a mile. His host, Captain Albert Cotton, said later that he had known the doctor for about ten years and he had arrived late and stayed to supper before.

At 10.30 p.m. Edward Jameson said he was in a hurry to get home and went away, Cotton letting him out but seeing no one about in the street. He had on his head his hard felt Muller-Cut-Down hat but carried no umbrella or stick. It was then very dark and just beginning to rain. He was, deposed Cotton, perfectly sober and walked quite straight.

Early next morning a wood reeve called Farrier went fishing down-river in the Stour for eels. At 6.30 a.m. he was coming back upstream when he saw a body floating face downwards in the water some thirty yards below the bridge. He had set out before sunrise, which had been at 5.31 a.m. that morning, and had seen nothing then.

The body was removed from the river and was soon identified as that of Edward Jameson. Mark you, no search had been instituted for the doctor in spite of the fact that he had been in a hurry to get home the night before and no alarm of any sort raised until his body was found.

This may strike you as curious.

The body was fully clothed save that his Muller-Cut-Down hat was missing. He had on an overcoat. There were several things in his pockets including a purse containing £3 15s 4d – a considerable sum at the time. The wood reeve noticed that the doctor’s watch had stopped at five o’clock. The clothing was in no way disarranged and according to the local newspaper report of the finding of the body (although not in the newspaper report of the inquest) there was a slight wound on the forehead.

The wood reeve went for the police and PC ‘Ginger’ Callaway took charge. He promptly and properly reported the body to the County Coroner, Mr R.M. Mercer. (It has only been since 1963 that the city of Canterbury and the county of Kent have shared a Coroner). You will remember that Dr Jameson had at one time been an assistant to the City Coroner, Dr T.M. Johnson.

The County Coroner decided to hold an inquest that very afternoon and a jury was summonsed to be at the Fordwich Arms public house at 5.30 p.m. The Coroner opened an inquest to determine how it was that the popular, amiable doctor, Edward Jameson, who knew the roads of the village like the back of his hand, who was a big and powerful man and a good swimmer, who had left Captain Cotton’s house quite sober at 10.30 p.m. had come to be found dead in the river, with a bruise on his forehead, at 6.30 a.m. the next morning with his watch stopped at five o’clock.

There had been barely time for PC Callaway to search for the missing hat, which was presumed to have fallen off as the doctor fell over the low wall at the bridge opposite The George public house. (The Dragon came later.) The Coroner asked him about this at the inquest. Callaway said the river had been dragged but the hat had not been found.

The Coroner said, ‘If it is assumed that the deceased fell over the wall at the bridge in the agile manner that has been suggested, surely his hat would have been found?’

The police constable (very rightly sticking to fact and refusing to be drawn into speculation) said, ‘I have searched the river but cannot find it anywhere.’

The Coroner took evidence from a neighbour who knew the doctor, Farrier, the wood reeve, and the policeman and that was all – there was no mention of brother Willy.

He went on to observe that as far as he could see there was not a scrap of evidence from which the jury could come to any verdict as to how the deceased had got into the river. It had been suggested that he had stumbled over the low railing on the left of the bridge and toppled. He, the Coroner, had carefully looked at the spot and certainly thought that was possible. He did not think there was any suggestion of foul play but they could not say actually when the deceased entered the water and there was nothing to show even that he went in at the bridge.

Under all the circumstances he felt that their verdict ought to be ‘found drowned between the hours of 10.30pm on 4th September and 5am on 5th September’. You’ve noticed that Freudian slip, haven’t you? He said 5 a.m. – the time the watch stopped – even though the body wasn’t found until 6.30 a.m.

So far, so good.

But not far enough and not good enough for the village jury.

They carefully considered their verdict and agreed that Dr Edward Jameson had been found drowned, adding firmly that, ‘How or by what means the deceased so came into the river there was insufficient evidence to show, but in the opinion of the jury, owing to darkness the deceased accidentally fell into the river on his way home.’

Grounds for a legend there, do you think?

Perhaps not.

There the legal proceedings rested. At the inquest begun and finished on Saturday, 5th September, within twelve hours of the body being found.

Between then and the afternoon of Tuesday, 8th September, but at a time I was unable to establish, a post-mortem examination was held.

A report of the findings appeared rather shyly under the anonymity of some person calling him or herself ‘A well-informed correspondent’ who wrote to the local paper, the Kentish Gazette, as follows:

It will no doubt be interesting to your readers to learn a few further particulars concerning the so-called mysterious death of the late Mr Edward Jameson, of Sturry. To throw further light on the subject it was thought necessary to have a post-mortem examination. This was held by Messrs Frank Wacher – [a famous name in Canterbury’s medical history; his house was also bombed in 1942] – and A.H.D. Salt, the former being appointed by the Scottish Accidental Employers’ Liability Insurance Company of Moorgate Street, London, in which the deceased was insured. [They aren’t there any longer.]

The results of the post-mortem examination showed that the deceased had received injuries on the left side of the head, left arm and both knees which were in themselves sufficient to render him insensible. The condition of the lungs was not that of drowning but suffocation; the stomach was full of undigested food, the state of the digestion proving that that he had come to his death very shortly after supper.

But it was proved that his watch had stopped at 5.00 a.m. This would seem to show that the deceased must have fallen into shallow water which only covered his head, but that owing to the heavy rain, the mill and other causes, the river rose by morning and it must have been about 5.00 a.m. that the body actually floated and the watch stopped.

Dynamite.

So the doctor wasn’t drowned at all but suffocated. And suffocated, in all probability, while insensible from injuries to head, arm and both knees – injuries, you will remember, described earlier as a slight bruise or wound of the forehead. And dead, as proved by the state of the digestion, very soon after leaving Captain Cotton’s house at 10.30 p.m.

What happened after that newspaper report?

First of all Edward Jameson’s mother, Harriet, took to her bed with an attack of paralysis and nervous aphonia and spoke to no one.

Secondly, a man called Harry Enston took on – or was paid to take on – the role of keeper to Willy Jameson and from that day forward was his constant companion – so constant a companion that Willy was never questioned or left alone with anyone. In fact, when Willy died in 1898, then aged forty-six, it was Harry Enston who was present at death and who registered it.

And what happened after that?

Very little.

The miller might have been asked if he had indeed opened the floodgates upstream at 5 a.m. that fateful morning. I don’t know. I do know that with the kind assistance of the Kent River Board (whom I am sure thought I was at least two sandwiches short of a picnic when I asked them) I calculated that high tide, such as it was, at the bridge at Fordwich would have been at 11.30 p.m. on the Friday evening and low tide therefore at 5.30 a.m. the next morning. Certainly any body – and I do mean ‘any body’ – would travel more than thirty yards in eight and a half hours in the River Stour, especially on an ebb tide flowing at three knots.

‘an attack of paralysis and nervous aphonia’

On the Monday evening a parishioners meeting unanimously agreed that they would send a wreath. The Cricket Club settled on what was called as ‘a characteristic floral token of a touching description’.

The funeral, taken by the Vicar, the Reverend George Billing, and attended by Willy as the only family mourner, was held on the Tuesday afternoon, the occasion being one of general mourning in all three local villages.

And then – I had a surprise.

Checking, some seventy years later, on the death certificate, I found that this had been received at the General Register Office, at Somerset House, on Thursday morning, September 10th from R.M. Mercer, Her Majesty’s Coroner for Kent, who certified that the inquest had been held on the day before, that is Wednesday, 9th September. The place of death was given as the River Stour and the cause ‘Found Drowned’ and it stated that Edward Jameson’s death had taken place on the previous Saturday, 5th September.

This may strike you as strange. It did me, too. I can’t explain how it is that if the report in the Kentish Gazette is correct on the one hand, the inquest was held on the Saturday, and on the other hand if the death certificate is correct that it was held the following Wednesday.

I can only say that if it was held on the Saturday it was before the post-mortem, which may strike you as unusual, (the more especially so since it was in the days when the jury were expected to view the body – super visum corporis), and if it was held on the Wednesday then not only was it held after the post-mortem but it was after the funeral, too, which is even more unusual.

Then what happened?

The Kentish Gazette, having dropped the bombshell about the post-mortem, got itself into a high state of indignation about the Armenian Massacres. The Sturry Cricket Club went ahead with their averages and recorded the late E. Jameson as having 23 innings, 5 times not out, 117 runs … some things are quite immutable, aren’t they? A public subscription was opened to pay for a gravestone. You can still see it by the north door of St Nicholas’ Church, at Sturry.

What you couldn’t see at the time is as good an example of professional solidarity as you’ll ever find, and completely hidden from 1896 until 1963, when I first looked into this murder – when a Coroner of all people knowingly put his head into a noose and risked his professional reputation and his medical career by acting for what he considered for the best to save the widow of a former colleague from losing her third – and last – son to the gallows.

And which of us shall say he was wrong?

MARGERY ALLINGHAM

Margery came from a literary family, and rose to prominence in the 1930s as the author of a series of increasingly ambitious and unorthodox novels featuring Albert Campion. Her best-known book is probably ‘The Tiger in the Smoke’, which was filmed in 1956, while Peter Davison played Campion in a BBC Television series in 1979-80. She also wrote three books under the pseudonym Maxwell March. Allingham’s husband, the artist Philip Youngman Carter, continued to write about Campion after her death, and the Margery Allingham Society flourishes to this day.

(20 May 1904–30 June 1966)

THECOMPASSIONATEMACHINE

MARGERYALLINGHAM

When William Herbert Wallace, mild, elderly, poker-faced agent of the vast Prudential Assurance Company, was committed for trial for the indescribably brutal murder of his wife with whom he had lived happily for eighteen years, it seemed as if every man’s hand was instantly turned against him.

Everybody, from the very children playing on the corner of the street to the public prosecutor himself, appeared prepared to declare him guilty almost without a second thought. Overnight, the warm human city of Liverpool, the great British shipping centre in which he had been such a respected resident for so many years, suddenly became hostile.

A machine came to his aid. In this strange, topsy-turvy story that made British legal history, the apparently cold and precise machine of his fellow insurance collectors’ union took the unprecedented and even dangerous step of holding a secret mock trial of their fellow member. The machine found him innocent on the evidence and in the end the machine saved his life.

It is not popularly supposed that there is much spontaneous charity to be found in the insurance business. Accountants neither deal in nor are romantic figures. So when Mr Hector Munro, Wallace’s solicitor – one of the few people in his home town who believed him not guilty – travelled to London one day in March 1931 to lay the story before the executive council of the Prudential Staff Union he must have wondered what hope he had of finding succour there.

The details had already been published in every newspaper in the Kingdom and the snap verdict from the ‘man in the street’ was ‘Guilty’.

Yet there was nothing so very obvious in the history of the crime.

It began on the night of January 19th when Wallace, who was a keen player, was due at the City Chess Club some way from his home, to take part in a match. Everyone knew he was expected to be there and there was even a notice to that effect on the board just inside the warm, smoke-laden shop. At seven o’clock a phone call came through for him from a man who said his name was Qualtrough. As Wallace had not yet arrived the message was taken by the captain of the club, a certain Mr Sam Beattie, who knew Wallace well. It appeared to be an ordinary commercial communication. Qualtrough said it was his daughter’s twenty-first birthday and he would like to see Mr Wallace the following evening at half after seven ‘about a matter of considerable importance to do with his business.’

People often take out endowment policies for their children as twenty-first birthday presents and Sam Beattie, realising that it sounded like a bit of luck for Wallace, wrote down the unusual name and the address, which was ‘25 Menlove Gardens East’. Wallace had no phone in his own home and there seemed nothing strange in him being called at the club where there was one.

Wallace came in some few minutes later and settled down to his board. He was engrossed in his opening move when Sam Beattie caught sight of him and went over to pass on the message. Wallace, a tall, thin, precise looking man of fifty odd, seemed interested but not excited. He commented on the name and remarked that he did not know Menlove Gardens East but supposed it must be in the Menlove Avenue area, a district some miles from his home. He wrote down the particulars, thanked Beattie and went on with his game, which he won after a struggle lasting two hours.

The next day he spent as usual making his collections and paying out sick benefits with none of the dozens of people he met noticing anything at all peculiar in his manner. Just after six in the evening he went home, changed his clothes as was his custom, and went out to keep his appointment with the then utterly unmysterious Qualtrough. According to his own story he left home about a quarter before seven and it was certainly proved true that he was seen on a tramcar twenty-five minutes away from his house ten minutes after seven that evening.

Meanwhile, a small boy, delivering milk at a little after half past six, saw and talked to Mrs Julia Wallace on her own doorstep. Five minutes later still, a second boy laid a newspaper on the same doorstep and, later that night, when the police were summoned, that paper was found, presumably read, on the kitchen table. Yet after she spoke to the milk boy and told him to hurry home to take care of his cold, Mrs Wallace was never seen alive again.

Wallace came home at a quarter before eight in a state of irritation. His journey has been fruitless. After wandering for miles and asking everyone he met including a constable on duty, he had discovered that there was no Menlove Gardens East in the city and no Qualtrough in the area. To add to his troubles his front door, which had a faulty lock, appeared to have stuck. Mr and Mrs Johnston, his next door neighbours, found him at the back of the house as they were going out.

‘Now the back door seems to be bolted,’ he said. ‘Have you heard anything unusual tonight?’

He tried it again and, as they watched, it moved.

‘Well, it opens now,’ Wallace muttered and went in. The Johnstons stood waiting, marking the flicker of his match as he passed through the house. They heard him call out twice as he reached the stairhead and then his light appeared in the back bedroom. Once more there was silence as he came down again and stepped into the tiny front parlour, which he and his wife never used unless they had visitors or wanted to have a little music, she at the old-fashioned piano and he at his new violin.

A moment later he came hurrying out to them and said in a nervous hurried voice, ‘Come and see; she has been killed.’

At a later date these words sounded unemotional to the point of callousness. In court they appeared so inadequate that they almost hanged Wallace; but that night, outside the dark little house, they did not strike the Johnstons as anything but frightful and they pressed in after him to the door of the small front room.

There the scene was horrific. Poor little Mrs Wallace had been murdered by eleven maniac blows, which had covered her and half the room beside with so much blood that the very walls were splattered with it. A blood-soaked mackintosh, doubled up and thrust under one shoulder, turned out to be Wallace’s own. He recognised it at once and volunteered the information that he has worn it that very afternoon and had left it hanging up in the lobby by the front door.

Mr Johnston rushed out to call the police and Mrs Johnston stayed with Wallace while he searched the house. From first to last this kindly neighbour was the only person who saw the prim, cold man show any sign of emotion at all at the appalling catastrophe. To her ‘he almost broke down twice but controlled himself immediately on each occasion’. Not a great show of grief perhaps, but it was something. No one else saw anything of the kind. Professor MacFall who examined the body for the police was particularly shocked. ‘Why,’ he exclaimed at the trial, ‘he was not so affected as I was myself!’

‘There the scene was horrific’

The police formed the notion that Wallace was implicated very early on in the inquiry and in one way it was fortunate for him, for they searched him very carefully that night and at once one of the most extraordinary features of the whole story became apparent.

Neither Wallace himself – on his clothes, on his boots, in his nails – nor in any part of the house save in that one terrible room was there any trace of blood whatever, although it was estimated that something over a quart had been spilled. Any man who had ever cut himself whilst shaving must appreciate the full significance of that discovery!

Since any case against the insurance agent had to admit that he could have had less than twenty minutes to kill his wife, remove all traces of blood from himself, hide or destroy the weapon (which was never discovered) and get himself on a tramcar to Menlove Avenue, the point was of importance. There was no sign of recent washing in bathroom or sink, no wet towels.

The house was only slightly disturbed and no robbery had been committed but it was admitted that at that particular time in the month anyone who knew anything of an insurance collector’s business might have supposed that there was a considerable sum of the Company’s money in the house.

The cloud of suspicion hung over Wallace like a vulture for several days and then the police made an astonishing discovery. By one chance in ten thousand, the telephone message from the mythical Qualtrough was traced. There had been a fault at the exchange at the time and the superintendent had made a note of the call and was able to say definitely that it came from one particular box not four hundred yards from Wallace’s own front door.

That was just enough. The police decided that he had telephoned the club himself on his way down there using a voice so disguised that it deceived an old friend like Beattie and had then, by some means unknown, reached the City Café in a much shorter time than the trip would normally have taken him. They saw his fussy enquiries round Menlove Avenue as an ingenious alibi and they arrested him.

He appeared before the preliminary court, where his unnatural calm and self-possession damned him, and he was committed for trial with all the big guns of the prosecution, advocates famous all over the country for their brilliance, ranged against him.

His entire life savings amounted to round about four hundred pounds and his defence, if it was to be at all adequate, must cost him something nearer fifteen hundred.

That was the story which Mr Munro had to lay before the Prudential Staff Union.

The thing he could not tell them, for it had not yet emerged from Wallace’s own writings, was the strange man’s peculiar belief in a stoic attitude towards misfortune. He belonged to that breed of Anglo-Saxon which has been somewhat flippantly described as the ‘stiff upper lip boys’. He clung to his pathetic dignity as if it was a pole sticking up out of the torrent and his human feelings as if they were indecent.

There were twenty executive members in the small office in the Gray’s Inn Road and at first the gathering was as cold towards Wallace as Wallace was thought to be towards the world. But gradually as the pure clear logic of the facts was retailed to them a new interest sprang up. It was not yet a conviction by any means but several facts of the truth, hitherto glossed over in the newspapers, had been given their real prominence. After he had stated his case Mr Munro was asked to leave.

What happened then is one of those rare romantic things which sometimes occur to prove that modern commercial companies and institutions, if machines, are not quite so soulless as they are so often supposed even by those who work for them.

Those twenty men shut themselves up in secret in the small office and produced not a resolution but a verdict.

On the authority of Thomas Scrafton, the president secretary, it can be said that both E.J. Palmer MP and W.T. Brown, who were in command at that time, always spoke of that remarkable meeting as ‘The Mock Trial at which Wallace was found innocent’.

Of necessity the proceedings were utterly private. The penalties for contempt of court – and a trial of this kind before the real one could only have been considered gross contempt – are very great. But the mock trial was held and the verdict was given.

The machine, having declared him innocent, then set out to help their colleague by every means in its power and from all over the Islands other insurance agents contributed, not so much to save a brother as to preserve an innocent man.

After that the fight was on. The well-known advocate Mr Rowland Oliver KC was briefed for the defence, and experts engaged to fight these other expert witnesses called by the prosecution.

The trial lasted four days. To account for the absence of blood on the prisoner, the astounding suggestion was made that Wallace had stripped save for his mackintosh and had persuaded his wife into the little-used front room to kill her so that he might escape naked upstairs to wash! Even so there was no vestige of a motive. Witness after witness insisted that the two people were happily married. There was no ‘other woman’. Wallace stood to gain nothing but loneliness from his wife’s death.

As last the Judge, representative of another cold and perfect machine, the Law, summed up in Wallace’s favour. As far as he was permitted to lead the jury he did so, pointing out to them every weakness in the long chain of circumstantial evidence. After he has spoken it seemed impossible that any twelve men could convict. But Wallace’s happy gift for controlling himself too perfectly did its work once again. There was nothing of the machine about the jury. After only an hour’s discussion they returned a verdict of guilty and the insurance agent was sentenced to hang.

Again the Prudential Staff Union stuck to the verdict of the Mock Trial. More funds were raised, an appeal was lodged and this time another and ever greater Machine of Justice behaved in a new way.

The Court of Criminal Appeal quashed the conviction on the grounds that the jury’s verdict of guilty was unreasonable and could not be supported by the evidence. No other conviction for murder has ever been quashed on these grounds in British legal history.

William Herbert Wallace was free: saved by the two unprecedented and romantic actions of two apparently rigid machines. The Prudential Assurance Company gave him back his job. But the men and women of his home town would have nothing to do with him and he crept away to die eighteen months later in a house in Cheshire which, so he wrote, always made him think how much his wife would have loved it.

The murderer was never found. Many people today believe still that Wallace was guilty but it is significant that in the house in Cheshire he fitted up an ingenious arrangement so that on returning home at night he could light up the whole house at a touch and see at once if any dark figure was waiting there to attack him …

MARTIN BAGGOLEY

Martin is a retired probation officer who lives in Ramsbottom. He has written a number of true crime books and is especially interested in murders committed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

THESTANFIELDHALLMURDERS

MARTINBAGGOLEY

On Tuesday, 5th December 1848, the lanes of Wymondham, nine miles to the south-west of Norwich, were lined with several hundred people, who were there to pay their respects at the funerals of fifty-nine-year-old Isaac Jermy and his twenty-seven-year-old son, also Isaac, both of whom were well known and much respected locally. The older man had been the Recorder of Norwich and a director of the city’s life insurance and fire insurance societies. His son had helped with the management of the family estate and their brutal murders a few days earlier had caused great sadness throughout the district.

The Recorder was a widower and lived in Stanfield Hall, which stood close to Wymondham. On the evening of 28th November, he dined there with his fourteen-year-old daughter Isabella, and his son and daughter-in-law Sophia, who had their baby daughter with them. At a little after eight, dinner was finished and Isaac senior left the table, as he often went out alone to stroll in the garden after a meal. He had been gone for a few moments only when the silence was shattered by a gunshot.

Those inside were unaware that he was lying dead in the porch and his killer had entered the house by a side door. On hearing the shot, the butler, James Watson, who was in the pantry, stepped into the corridor and was immediately pushed aside by the killer. Young Isaac had also heard the shot and was by this time emerging from the dining room, intending to make for the front of the house. However, he did not make it and the butler watched helplessly as the intruder pointed a gun at the young man and fired, killing him instantly.

Sophia grabbed the baby and followed her husband into the corridor, where, on seeing his body, screamed and began to sob uncontrollably. She was heard by the housemaid Eliza Chestney and the cook Margaret Read, who were in the servants’ quarters. Eliza was the first to reach her mistress and as she attempted to console her, the killer came out from behind a door and shot both women. Eliza was wounded in the leg and Sophia’s elbow was very badly damaged. Margaret reached them as the killer was running out of the house and she was joined by the nursemaid, Maria Blanchflower, who had been in her bedroom. They comforted the badly wounded women until the police and medical assistance arrived.

Norwich surgeon William Nicholls treated the wounds of Sophia and Eliza, both of whom would survive, before examining the bodies of the two men. There was a large open wound to Isaac senior’s left side, two inches above the nipple. Mr Nicholls removed a great number of slugs from the corpse, found three broken ribs and noted the heart had been almost totally destroyed. Many pieces of lead were also taken from Isaac junior’s body and there was a massive wound at his right nipple, two of his ribs were in pieces and the fatal injury was to the heart.

The police found there was confusion surrounding the one or more weapons used in the shootings. James Watson insisted the killer had a pistol in each hand, but Margaret Read saw only one firearm. There was no trace of a weapon but the killer dropped a ramrod, and two handwritten notes were left behind, which read:

There are seven of us here, three of us outside and four of us inside the hall, all armed as you see us two. If any of you servants offer to leave the premises or to follow us, you will be shot dead; therefore, all of you keep to the servants’ hall and you nor anyone else will take any harm, for we are only come to take possession of the Stanfield Hall property.

THOMAS JERMY, the Owner.

Mrs Jermy was too badly injured to be interviewed but the servants reported the killer wore a long cloak and was heavily disguised in a false wig and bushy beard. Nevertheless, the butler, cook and housemaid were adamant that he was local farmer James Blomfield Rush, a regular visitor to the house and well known to them. All had noticed the man was short, stout, had broad shoulders and they commented on his distinctive gait. Only Maria Blanchflower could not be positive, but she had not worked at the Hall for long and did not know Rush well. At five thirty the following morning, several police officers, led by Inspector George Pont, visited Rush at his home, Potash Farm, which was about a mile from the murder scene, where he was arrested on suspicion of committing the murders. A search of the farmhouse yielded a cloak similar to that which the killer was said to have worn, together with a wig and false whiskers.

The case against Rush was strengthened when police later interviewed Mrs Bailey, a servant of the Jermys, who recalled Rush approaching her in the grounds of the mansion at about five on the evening of the murders, asking who would be dining there that night. She told him and noticed him walking towards a young woman who was just leaving the Hall. This proved to be dressmaker Elizabeth Cooper, who reported Rush was keen to confirm that father and son were both at home.

To better understand the circumstances surrounding the murders and why Rush was regarded as a suspect, it is necessary to look at events which occurred a decade and more earlier. Stanfield Hall was a large moated country house, which was inherited by the Reverend George Preston towards the close of the eighteenth century. It stood in 800 acres of land and included several cottages and farms. George died in 1837, leaving the estate to his son, Isaac Preston. It was known that more than a century earlier, a forebear had left a will stating that the property should not be occupied by anyone who did not have the surname Jermy, but it was believed this had no legal standing and contact was no longer kept with that branch of the family.

However, in the summer of 1838, Isaac held an auction of his late father’s possessions at the Hall and on that day was approached by two men, John Larner and Daniel Wingfield, who told him they were there to claim the estate for the Jermys, who were the rightful owners. Isaac was ordered to leave immediately with his family and servants. Of course, he refused to do so and called for the police, who ejected the two men. This did not prevent Larner and Wingfield persisting with the claim and on 24th September, with a number of other men, they occupied the Hall for much of the day, having forced Isaac and his family to leave. The militia arrived and following their arrests the occupiers were detained in the gaol at Norwich Castle.

At the assizes held the following March, Larner and Wingfield were convicted of simple riot and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment. A more serious charge, which could have led to the pair being transported, was dropped, apparently on the understanding no more attempts to acquire the property would be made either through the courts or by direct action. As a further insurance, Isaac changed his family’s surname from Preston to Jermy and believed the matter was closed.

Forty-eight-year-old Rush was born the illegitimate son of Mary Blomfield, who in 1802 married farmer John Rush, who accepted her son as his own and who, in 1811, rented a farm in Felmingham from Reverend Preston. In 1828, James, who had followed his stepfather into farming, married and he and his wife Susannah eventually had nine children. In 1835, James rented a farm neighbouring that of his stepfather, from Reverend Preston, who enjoyed good relationships with his two tenants.

Following his landlord’s death, James Rush purchased Potash Farm from Isaac Preston. A mortgage of £5,000 was agreed, which was to be repaid in full ten years hence, on 30th November 1848, which, with interest, would require a one-off payment of £7,000. By the early 1840s, members of John Rush’s family occupied the farm at Felmingham, another on the estate, known as Stanfield Hall Farm and Potash Farm. Unfortunately, James would prove to have little business acumen and he quickly fell into debt. However, he was able to survive after benefitting financially following the untimely deaths of his stepfather, wife and mother between 1844 and 1848.

In October 1844, John Rush died in suspicious circumstances following the supposed accidental discharge of a gun, when his stepson was the only other person in the room at the time. A few weeks later, Rush’s wife died unexpectedly. In 1848, his mother died and she left her fortune of several thousand pounds to her grandchildren. It was believed that Rush forged his mother’s signature on a document stating the youngest child must reach eighteen years of age before any of them could inherit a share of their inheritance, which led to him retaining control of the money for the foreseeable future.

By this time, Rush had been evicted from Stanfield Hall Farm because of unpaid rent but remained in Potash Farm and his son continued to manage the farm at Felmingham. He was now in serious debt and his creditors applied to have him declared bankrupt. However, having gained control of his late mother’s fortune, he offered to repay the debts at the rate of twelve shillings in the pound. All agreed to accept the offer except for Isaac Jermy, as he suspected that shortly before his mother’s death, Rush had sold her a great deal of valuable equipment and livestock at a price very much less than the true value. Isaac insisted the documentation relating to the transactions did not reflect the actual amount of cash he received from her. He had thus misled his creditors and kept a large amount of money hidden away and out of their reach. As a result of his landlord’s stance, Rush was bankrupted in the autumn of 1848. It was claimed that Rush chose to murder the Jermys as a means of avoiding paying the £7,000 mortgage, due two days after the killings, and also as revenge on the men he blamed for his problems.

Rush had recently written a pamphlet entitled A Case; Jermy v Jermy Showing the Rightful Heir and Owner of the Stanfield Hall Estate