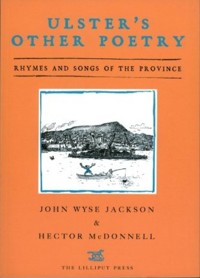

Ulster's Other Poetry E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

ULSTER' S OTHER POETRY proves that the people of Ulster have never been humourless or dour. Far from it. With its sparkling variety of rhymes, songs and humorous poems from every tradition of the province, the book demonstrates that those who dwell in the northern quarter of Ireland have their own unique take on the strange ways of the world, coupled with a whole-hearted appreciation of good fun. Spanning over three centuries of Ulster's past, this anthology is full of comic pleasures. In its pages, country ballads jostle with city satires, songs aimed at children meet jingles advertising bread, and university light verses encounter the folk-poems of the Antrim weavers. Each poem comes with background information about its origins, and each page is illuminated by Hector McDonnell's wonderful, witty drawings. This book is destined to become a much-thumbed, much-loved companion.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 138

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ULSTER’S OTHER POETRY

Rhymes and Songs of the Province

Edited by John Wyse Jackson and Hector McDonnell

The book is dedicated, with love, to Coll and Hannah McDonnell and to Conor and Adam Jackson.

Contents

(Verses are arranged alphabetically by author or, if anonymous, by title. Inverted commas denote working titles supplied for this edition.)

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Allingham, William, Irish Annals

The Ass and the Orangeman’s Daughter (Anon.)

The Athens of the North, 1937 (Anon.)

Barnett, George, Kelly’s ‘Slip-Tail’ Cow

Boyle, Francis, The Coal Hole

Browne, Harry T., The Wong

The Buncrana Train (Anon.)

Campbell, James, The Epicure’s Address to Bacon

Campbell, John, The Place

Faceless Magee

Carnduff, Thomas, On the Night-Shift

Celtic Revival (Anon.)

Christie, Grizel, Fantasy

Clifford, John, Wullie Boyd’s Flail

Craigbilly Fair (Anon.)

Dickey, John, Be this my Lot

Doyle, Lynn C., The Discovery

French, Percy, The Mountains of Mourne

Gallen, John, Prothalamion for KF

Gawn, Robert, Nineteen and Sixty

Gregory, Padric, The Ninepenny Pig

Haslett, Albert, Holy Water

Howard, Crawford, St Patrick and the Snakes

The Diagonal Steam Trap

In Vino Veritas (Anon.)

Jarvis, John, The Hurricane

Jennings, Paul, Ballyburbling

Juniper Hill (Anon.)

Kearney, Felix, The Blitz

Kelly, John ‘Paul’, Millar’s Jam

Kennedy, Jimmy, Teddy Bears Picnic

‘Kennedy’s Bread’ (Anon.)

McAtamney, Mick, The Irish Flea

MacConnell, Mickey, The Man who Drank the Farm

Marshall, W.F., Me an’ me Da

Masterson, Seán, Granum Salis

Mellor, W., The Ballyboley BudgieShow, 1953

My Aunt Jane (Anon.)

O’Kane, James, The Grass-Seed Market

On the Arrival of the Earl and Countess of Antrim with their First Born Son (Anon.)

O’Neill, Moira, Never Married

Porter, Hugh, The Making of a Man

Four Epitaphs

Ritchie, Billy, Paddy’s Prayer

Robert Ritchie, Swine Butcher (Anon.)

Ros, Amanda M’Kittrick, The Old Home

The Engineer Divine

Old Ireland

Love

Rowley, Richard, Poachin’ Tom

Scott, James H., Nonsense Hum (attrib.)

Shane, Elizabeth, Wee Hughie

Simmons, James, Epigram

Stewart, William R., The Meharg Brothers

The Tar Engine on the Coast Road (Anon.)

Thackeray, W.M., Peg of Limavaddy

The Thrashing Machine (Anon.)

Three ‘Remnants’ (Anon.)

Vint, F.F., The Wife

The Way of All Flesh (Anon.)

The Wee Pickle Tow (Anon.)

Young, Robert, Song

Impromptu to Mr Charles Agnew

Alexander, Mrs Cecil Frances, The Legend of Stumpie’s Brae

Acknowledgments and Thanks

Index of Titles and First Lines

About the Author

Copyright

Introduction

Like many another desperate person searching for something to say I find myself groaning and gazing out of the window. The little north Antrim glen I am looking at sweeps away down to the sea, and in the distance, bobbing on a watery horizon, are two blobs of land. I can never see those blobs without grinning, inwardly at least, as I remember an uncle who, when told what they were called, remarked, ‘Ah, perfect names for guests at a grand Scottish house party, “the old Mull of Kintyre and his daughter Ailsa Craig.”’

Those Scottish blobs often look so near that you cannot believe they belong to a different country, and I have only to listen to any of my neighbours talking to know how close we in fact are. Words and phrases that tripped off Robbie Burns’ tongue are still in daily use, though to people from other corners of Ireland they sound just as foreign as they do to any visiting English. Local culture continues undeterred here, in spite of its incomprehensibility to outsiders, and farmers still go onto the moss to cut their peats with a loy, or come back after a bad day’s wroughting on the land drenched in clabber to their oxters after falling into a sheugh.

There was a wee fella frae Clough

Who was fu’, and fell in till a sheugh …

Most of the verses in this book are the work of poets proudly aware of how special, and different, their particular corners of Ulster are, when compared to anywhere else. Inevitably, even though I am a fellow Ulsterman, many of them refer to things I have never really known: to wartime bombings, to university idylls, to academic literary disputes, to Belfast streets and shipyards, to unpleasant voyages, to incidents in ‘the Troubles’, to linen looms and indeed to digging for gold. But even though the localities and times of these poems may lie far from my own experiences, in their very familiar tones and twists and accents, they reward me with a strong sense of home.

There is, I believe, in Ulster a very particular and effective brand of humour – something that might be described as ‘the bull’s memory of the china shop’ (to rip out of context a brilliant line by the Ulster poet Tess Hurson). My own earliest experiences of the power of this poetical fun came from children’s parties, where one or other of our beloved local poets would inevitably stand up to do his party piece. One of them, Robert Morrow, who was my best adult friend in those days, would always terrify us with a versified account of going to the dentist to have a bad tooth pulled out, and its inevitable grisly climax:

Hold on there Robert

It’s out! It’s out!

Having finished that performance Robert would put a box of matches on the floor, stand up straight, carefully balance a full glass of water on the top of his head, slowly slide down until he was lying on the ground, clamp his remaining teeth round the matchbox and get up again without spilling a drop. It was a time blessed with as many such lyrical pleasures as anyone could ever hope for.

As we worked on this collection, many hours were enjoyably spent by John Wyse Jackson, my co-compiler, and myself, rummaging through long-forgotten books and magazines in dusty libraries, but an equal amount of energy was devoted to exploring personal poetry collections, and in particular one assembled by another great local entertainer, Mat Meharg. I maligned his family abominably in our first volume, Ireland’s Other Poetry, imagining that a surviving brother had locked all his poems in a cupboard and would let no one near them. In fact it is his sister who still lives in his house, and when I summoned the courage to visit her she was totally delighted to let me spend as much time as I wished with Mat’s boxes of poems, and indeed she even appears to have forgiven me my extreme silliness in telling my fanciful tale.

To my surprise, with one possible exception none of the poems in this unique archive of Ulster wit was by Mat himself; he had rather spent his time collecting and reciting the poems of other people. Without his hard work this book would be nothing like as good as it is, and so in partial thanks I reproduce here an anonymous ode to Mat who, when he wasn’t entertaining the locality with extracts from his personal anthology, became the local taxi firm, cycle shop and garage. I suspect that the anonymous author was actually Mat himself, but whether he was or he wasn’t I can just see him charming every pretty girl who caught his eye at a party by reciting it, and making her feel that he had composed it on the spot just for her. (The acronyms refer to his sometime employers, a long-vanished firm of local fuel providers.)

I’m M.S. Meharg of the E.D.C.P.

I’m fond of the lassies and a wee cuppa tea.

One day down at Esso House I chanced for to see

A bonny wee lass wi’ a glint in her e-e.

Says I to that lassie will ye walk for a while,

I’ll buy you a bonnet so we’ll do it in style,

My stripes are the Esso of E.D.C.P.

She looked at me shyly, and then said to me:

An Esso Boy for me, an Esso Boy for me,

If you’re no an Esso Boy, you’re no use to me.

The Shell boys are bra, Lebites an a’,

But the smilin’ wee Esso Boy’s the pride o’ them a’.

I courted that lass neath an oak tree,

I made up my mind she was fashioned for me,

Soon I was thinking how nice it would be

If she joined up in the Esso wi’ me.

The day we were wed the grass was so green

An’ the sun shone so bright as the light horiseen.

Now we’ve two bonny lassies who sit on her knee

While she sings the song that she once sang to me:

An Esso Boy for me, an Esso Boy for me,

If you’re no an Esso Boy, you’re no use to me.

The Shell boys are bra, Lebites an a’,

But the smilin’ wee Esso Boy’s the pride o’ them a’.

Very many of the verses in this book have a similar strength and vitality, because they were composed by Ulster people who simply wished to entertain other members of the community. In their various ways they amply compensate for any absence of purely ‘literary’ ambition with their robustness, pithy wit and good common sense. May this book give as much pleasure as any of those local childhood parties I still remember so vividly. That wonderful figure, Jimmy Kelly, the local road mender who was the composer of several poems in Ireland’s Other Poetry, and who appears in a poem in this one, would, I believe, have approved of it. Verse was inextricably part of Jimmy’s daily life. Often enough he would start proclaiming in rhyme as soon as he saw you coming, and always he created laughter. One day the local doctor saw him at work while driving along the coast road, and stopped to introduce him to his newly arrived and very attractive nurse – who had only taken the job because she was already walking out with another of the locals. So, Doctor Brennan wound down the window and began, ‘Jimmy can I introduce you to …’ but before he could say any more Jimmy looked in through the open window at them and pronounced,

You may sit beside her but you must not touch her,

For she’s engaged to MacAllister the butcher.

Hector McDonnell

William Allingham

Though he is sometimesrather lazily called ‘The Bard of Ballyshannon’, William Allingham (1824–89) is hardly thought of as an Ulster poet at all. He once summed up the problems of his own nationality in a succinct verse:

An Englishman has a country,

A Scotchman has two,

An Irishman has none at all—

And doesn’t know what to do.

A native of Donegal, in early life Allingham wrote ‘traditional’ ballads to airs by local musicians for sale as penny broadsheets. After many years as an Irish customs official, he left the airy mountains and rushy glens for England, where he edited magazines and gossiped with many of the great figures of Victorian literature. Alfred, Lord Tennyson, then Poet Laureate, became a good friend – despite his assertion that ‘Kelts are all mad furious fools!’

In 1851 the final volume of John O’Donovan’s English translation of the Annals of the Four Masters appeared, and Allingham wrote this spirited précis of the book, no doubt confirming Tennyson’s opinion of the wild Irish. The lines were eventually published in By the Way (1912), a posthumous collection of the poet’s fragments and notes.

IRISH ANNALS

MacMurlagh kill’d Flantagh, and Cormac killed Hugh,

Having else no particular business to do.

O’Toole killed O’Gorman, O’More killed O’Leary,

Muldearg, son of Phadrig, killed Con, son of Cleary.

Three show’rs in the reign of King Niall the Good

Rain’d silver and honey and smoking red blood.

Saint Colman converted a number of pagans,

And got for his friars some land of O’Hagan’s;

The King and his clansmen rejoiced at this teaching

And paused from their fighting to come to the preaching.

The Abbot of Gort, with good reason no doubt,

With the Abbot of Ballinamallard fell out,

Set fire to the abbey-roof over his head,

And kill’d a few score of his monks, the rest fled.

The Danes, furious pirates by water and dry-land,

Put boats on Lough Erne and took Devenish Island;

The Monks, being used to such things, in a trice

Snatching relics and psalters and vessels of price,

Got into the Round-Tower and pull’d up the ladder;

Their end, for the Danes lit a fire, was the sadder.

Young Donnell slew Rory, then Dermod slew Connell;

O’Lurcan of Cashel kill’d Phelim his cousin

On family matters. Some two or three dozen

Of this Tribe, in consequence, killed one another.

MacFogarty put out the eyes of his brother

James Longthair, lest James should be chosen for chief.

At Candlemas, fruit-trees this year were in leaf.

King Toole, an excitable man in his cups,

Falls out with King Rorke about two deerhound pups,

And scouring the North, without risking a battle

Burns down all the houses, drives off all the cattle;

King Rorke to invade the South country arouses,

Drives off all the cattle, burns down all the houses.

If you wish for more slaughters and crimes and disasters

See, passim, those annalists called ‘The Four Masters’.

Anonymous

If Allingham’s first interest was in folksong, so too, generations later, was Richard Hayward’s (1892–1964). This now half-forgotten Ulsterman was probably at heart an actor, but he was also an enthusiastic singer, film-maker, harper, folklore collector and anthologist, and a fine and companionable writer of travel books such as The Corrib County (1943) and Border Foray (1957).

In 1924, Hayward summed up for the Ulster Review the essence of what he called the ‘Ulster Quality’: ‘The hard commonsense. The hatred of pose. The terrific sense of humour. The pride of race. The belief that an Ulster man has no business with a Chelsea accent.’

He came across the following enjoyable survival in Co. Cavan, and included it in his 1925 anthology, Ulster Songs and Ballads of the Town and the Country. It demonstrates all the attributes required for Ulsterness, and should on no account be recited in a Chelsea accent.

THE ASS AND THE ORANGEMAN’S DAUGHTER

In the County Tipperary, at a place called Longford Cross,

There dwelt one Thomas Brady, who had a stylish ass;

But he was seized by heresy and canted was for tithes,

And on Forren’s Hill you’ll see these news; and his name was Henry Boyd.

This ass was sold by auction for a monstrous sum of debt

And was purchased by an Orangeman, which caused him for to fret;

For he tied him with a cable, and fettered him across,

And confined him in a stable with neither food nor grass.

For three long days he was kept there with not one bit to ate,

And on the morning of the fourth in walks the daughter Kate;

She opens a large Bible and begins to read, with hope,

And says she: Me paypish donkey now, you must deny the Pope.

If you’ll become an Orangeman and join King William’s host,

And deny infallibility and all that kind of boast,

You shall be set at liberty, and feed on oats and hay,

And decent prayer you yet may hear on every Sabbath day.

My charming lass, replied the ass, the truth I now must tell,

But first of all I’ll ask you for to kindly go to hell;

I never will deny the sacred emblem of the Cross,

For I wear it on my shoulder though I’m only just an ass.

Miss Kate she frowned and answered, saying: How dare you me refuse!

I’ll make you suffer very sore before you do get loose.

I’ll whip your hide until your side looks like a piece of beef,

And where’s the paypish squirt-boy that dare come till your relief?

This Orange lass she seized a stick to knock the donkey down,

When a multitude of asses full soon gathered there around;

And they tore her flounces into rags, and set the donkey free,

To show this Orange termagant they’d fight for liberty.

Anonymous

Purists may point out that the verses below violate our working definition of ‘Other Poetry’, since they have neither rhymes nor a regular metre. However, they make up for it in so many other ways that it would be foolish indeed to exclude them on a technicality.

Under the unidentified initials ‘B.S.’, the lines appeared in the autumn of 1937 in the New Northman