Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

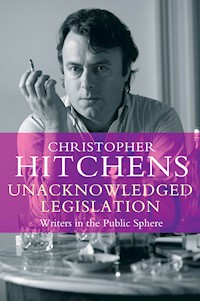

A celebration of writers and their encounters with politics and public life from one of our greatest critics. Unacknowledged Legislation is a celebration of Percy Shelley's assertion that 'poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world'. In over thirty magnificent essays on writers from Oscar Wilde to Salman Rushdie, and with his trademark wit, rigour and flair, master critic Christopher Hitchens dispels the myth of politics as a stone tied to the neck of literature. Instead, Hitchens argues that when all parties in the state were agreed on a matter, it was the individual pens that created the space for a true moral argument. I have been asked whether I wish to nominate a successor, and inheritor, a dauphin or delfino. I have decided to name Christopher Hitchens. - Gore Vidal

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 791

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

UNACKNOWLEDGED LEGISLATION

First published in 2000by Verso

This edition published in Great Britain in 2014 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Christopher Hitchens, 2000

The moral right of Christopher Hitchens to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 468 6E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 498 3

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Salman. As ever.

Allons travailler.(Closing words of Emile Zola in L’Oeuvre)

CONTENTS

Foreword

I. ‘In Praise of …’

The Wilde Side

Oscar Wilde’s Socialism

Lord Trouble

George Orwell and Raymond Williams

Oh, Lionel!

Age of Ideology

The Real Thing

The Cosmopolitan Man

After-time

Ireland

Stuck in Neutral

A Regular Bull

Not Dead Yet

II. ‘In Spite of Themselves …’

Old Man Kipling

Critic of the Booboisie

Goodbye to Berlin

The Grimmest Tales

The Importance of Being Andy

How Unpleasant to Meet Mr Eliot

Powell’s Way

Something about the Poems

The Egg-head’s Egger-on

Bloom’s Way

III. ‘Themes …’

Hooked on Ebonics

In Defence of Plagiarism

Ode to the West Wing

IV. ‘For Their Own Sake …’

O’Brian’s Great Voyage

The Case of Arthur Conan Doyle

The Road to West Egg

Rebel in Evening Clothes

The Long Littleness of Life

V. ‘Enemies List …’

Running on Empty

Unmaking Friends

Something For the Boys

The Cruiser

Acknowledgements

Index

FOREWORD

WRITING IN RESPONSE to Thomas Love Peacock, who had said that ‘a poet in our time is a semi-barbarian in a civilised community’, Percy Bysshe Shelley proclaimed in 1821 that:

Poets are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration; the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present; the words which express what they understand not; the trumpets which sing to battle, and feel not what they inspire; the influence which is moved not, but moves. Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world. [Italics mine.]

The fate of his polemic In Defence of Poetry (which is customarily pared down to comprise only the last sentence of the above paragraph) is not untypical of the fate of radical freelance work in all ages. The magazine to which it was sent, and which had printed Peacock’s original remarks, ceased publication almost as soon as the riposte had been composed. Shelley then hoped to publish it in the pages of The Liberal, a periodical launched by Byron and Leigh Hunt. But The Liberal, too, expired in the grand tradition of noble-minded and penurious reviews. Shelley died long before his essay saw print. His widow, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, got it into publication eighteen years after his decease, omitting several of the references to Peacock. Thus, we owe our too-easy familiarity with an attenuated aperçu to the belated efforts of the author of Frankenstein, who was also the daughter of the authors of Political Justice and A Vindication of the Rights of Women.

Frankenstein’s unhappy creation allows me an easy transition to the following, which was written by W. H. Auden in August 1968. (August1968, following Auden’s fondness for numinous dates like 1 September 1939, is also the title of the poem):

The Ogre does what ogres can,

Deeds quite impossible for man,

But one prize is beyond his reach,

The Ogre cannot master Speech.

About a subjugated plain,

Among its desperate and slain,

The Ogre stalks with hands on hips

While drivel gushes from his lips.

This was penned in hot and immediate response, from just across the Austrian frontier, to the Soviet erasure of culture and democracy in Czechoslovakia in that very month. I happened to be in Havana at the time and on my way to Prague, and was very much struck – without registering it anything like so acutely – by the awful rhetoric and terminology employed by defenders of the Warsaw Pact invasion. The hideous term ‘normalisation’, a sort of apotheosis of the langue du bois, was the name given to the subsequent ‘restoration of order’.

Twenty-one years later, the mighty occupation-regime installed by the full weight of Panzerkommunismus (Ernst Fischer’s caustic word for it) collapsed amid laughter and ignominy, without the loss of a single life, as a consequence of a civil opposition led by satirical playwrights, ironic essayists, Bohemian jazz-players and rock musicians, and subversive poets. Life in the Czech lands, and the Slovak lands too, may since have become much more banal and, so to say, prosaic. But would it be merely ‘romantic’ to say that Auden, in 1968, had been somehow aware of ‘the gigantic shadows that futurity casts upon the present’? ‘Moved not’, or not so much as moving, he had prefigured the end of a system which depended on gibberish and lies. The sword, as we have reason to know, is often much mightier than the pen. However, there are things that pens can do, and swords cannot. And every tank, as Brecht said, has a crucial flaw. Its driver. Suppose that driver has read something good lately, or has a decent song or poem in his head …

Invited recently by the Los Angeles Times to contribute to one of those symposia on ‘Politics and the Novel’, I was asked to name the works of fiction that had had most influence upon me. Novels were specified; even so I should have said ‘the war poems of Wilfred Owen’. These are neither novels and nor, in one important sense, are they fictional or imaginary. But I shall never be able to forget the way in which these verses utterly turned over all the furniture of my mind; inverting every conception of order and patriotism and tradition on which I had been brought up. I hadn’t then encountered, or even heard of, the novels of Barbusse and Remarque, or the paintings of Otto Dix, or the great essays and polemics of the Zimmerwald and Kienthal conferences; the appeals to civilisation written by Rosa Luxemburg in her Junius incarnation. (Revisionism has succeeded, in many cases justly, in overturning many of the icons of Western Marxism; this tide, however, still halts when it confronts the nobility of Luxemburg and Jean Jaurès and other less celebrated heroes of 1914 – such as the Serbian Dimitri Tucovic.) I came to all these discoveries, and later ones such as the magnificent Regeneration trilogy composed by Pat Barker, through the door that had been forced open for me by Owen’s ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’. So it’s highly satisfying to read again his poem ‘A Terre (Being the Philosophy of Many Soldiers)’ and to come across the lines:

Certainly flowers have the easiest time on earth.

‘I shall be one with nature, herb and stone’, Shelley would tell me.

Shelley would be stunned: The dullest Tommy hugs that fancy now.

‘Pushing up daisies’ is their creed, you know.

A true appreciation of Shelley; to find a dry and ironic use for him in the very trenches. Most of Owen’s poetry was written or ‘finished’ in the twelve months before his life was thrown away in a futile action on the Sambre-Meuse canal, and he only published four poems in his lifetime (aiming for the readers of the old Nation and Athenaeum, and spending part of his last leave with Oscar Wilde’s friend and executor Robert Ross, and with Scott Moncrieff, translator of Remembrance of Things Past). But he has conclusively outlived all the jingo versifiers, blood-bolted Liberal politicians, garlanded generals and other supposed legislators of the period. He is the most powerful single rebuttal of Auden’s mild and sane claim that ‘Poetry makes nothing happen’.

The essays in these ensuing pages were all written in the last decade of the twentieth century; between the marvellous humbling of the Ogre and the onset of fresh discontents. They do not engage with political writers so much as with writers encountering politics or public life. I don’t deal exclusively or even principally with poets either, but I have looked for those who try and raise prose to the level of poetry (from Wodehouse and Wilde, to Anthony Powell’s ear for secret harmonies and unheard melodies). Another and more blunt way of stating my own ambition is to recall Orwell’s desire to ‘make political writing into an art’. Sometimes, and less strenuously, I have attempted to show how some artists have almost involuntarily committed great political writing.

The intersection where this occurs is an occasion of paradox, or of epigram and aphorism. One still pays attention when Wilde says that socialism, properly considered, would free us of the distress and tedium of living for others. And one lends an ear when Orwell – so crassly termed a ‘saint’ by V. S. Pritchett – announces that saints must always be adjudged guilty until proven innocent. Lionel Trilling once alluded to ‘the bloody crossroads’ where literature and politics meet, and this phrase was annexed by the dire Norman Podhoretz (who is to Trilling as a satyr to Hyperion) for the title of a notorious and propagandistic book. But properly understood and appreciated, literature need never collide with, or recoil from, the agora. It need not be, as Stendhal has it in Le Rouge et Le Noir, that ‘politics is a stone tied to the neck of literature’ and that politics in the novel is ‘a pistol shot in the middle of a concert’. The openly, directly politicised writer is something we have learned to distrust – who now remembers Mikhail Sholokhov? – and the surreptitiously politicised one (I give here the instance of Tom Wolfe) is no great improvement. Gabriel Garciá Márquez has paid a high price for his temporal allegiances, as have his patient readers. But in the work of Tolstoy, Dickens, Nabokov, even Proust, we find them occupied with the political condition as naturally as if they were breathing. Which is what Auden must also have meant when he wrote, in obeisance to a man whose public opinions he actively distrusted, (‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’: February 1939):

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent,

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique,

Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honours at their feet.

Time that with this strange excuse

Pardoned Kipling and his views,

And will pardon Paul Claudel,

Pardons him for writing well.

Nothing is lost, from these verses, in contemplation of the fact that Auden removed them, and many other exquisite poems and passages, from his own canon in a boring attempt to re-establish himself as a man of Anglican integrity. (Also, the rehabilitation of Paul Claudel may take a little longer than he surmised.)

I cannot apologise for the fact that my subjects are almost all English or American or Anglo-American. For one thing, I am mainly English and have no real competence in any other tongue. For another, the Anglo-American idiom is well on its way to being what Kipling and others always hoped for, albeit in a different guise: a world language. A world language, that is, without being an imperial one. (Indeed, at least in some ways, the first to the extent that it has ceased to be the second.) The written record of English literature is also a powerful and flexible instrument for the understanding of British and perhaps post-British society – a point to which I want to recur. While in America, the role of the writer is given exceptional salience by the fact of the United States being a ‘written’ country, based on a number of founding documents that are subject to continuous revision and interpretation. No clause in the Constitution mandates an opposition party; indeed the whole document is designed to evolve orderly consensus. But the First Amendment, which places freedom of expression on a level with freedom of (and freedom from) religion, grants the writer wide powers. In my graduate class on ‘Unacknowledged Legislators’ at the New School in New York, which gave me the title of this book, I sought to show how often, when all parties in the state were agreed on a matter, it was individual pens which created the moral space for a true argument. Some chief instances would be Thomas Paine on the issue of independence and anti-monarchism, Garrison and Douglass on slavery, Mark Twain and William Dean Howells on imperialism, and Upton Sinclair and John Steinbeck on the exploitation of labour. But nearer to our own time, there was the disruption by Norman Mailer and Robert Lowell of the unspoken agreement on a war of atrocity and aggression in Indochina. And of course, we have Gore Vidal’s seven-volume novelisation of American history, a literary attempt at the creation of what he terms ‘a usable past’.

Although admittedly borne around the globe partly on the shoulders of a homogenising American commerce, another way in which English has become a language of universals is the form in which it has been annexed by its former colonial subjects. Here, the critical figure has been Salman Rushdie. Ever since his magnificent evocation of combined partition and parturition in Midnight’s Children, he has been raising a body of work which, while deeply based in the love and study of classical English letters, truly deserves the name of cosmopolitan. By his experiments with language and dialect and his conscription of musical themes, he has approached the closest to poetry in prose. He is also, in such a way as to make it indissoluble from his other themes, a political writer for an emerging multi-national and (perhaps this needs no emphasis) secular readership. In 1989, just as the Ogre was about to collapse, Salman was criminally assaulted by a simultaneous death sentence and life sentence, a fatwah issued by a moribund theocrat. The intervening ten years, in which the forces of mercenary assassination and religious coercion were opposed by the weapons of wit and reason, involved a campaign with which I am extremely proud to have been associated. As I write, it is the discredited mullahs who have to answer to a host of independent and critical literary voices in Iran. Nothing could be more satisfying than this outcome. The summa of the published record is a book, originally in French and entitled Pour Rushdie, in which almost every writer of worth in the Arab and Iranian and wider Muslim world took Salman’s side, and identified his cause with their own hopes for emancipation. This volume was the finest possible repudiation of all the Western conservative elements who claimed to see merit in the Ayatollah’s condemnation of blasphemy. ‘Is nothing sacred?’ Of course not. Aptly enough, perhaps, the best defence of Rushdie as a profane and revolutionary writer in the great tradition of Joyce and Rabelais was written by Milan Kundera, literary eminence of the Czech cultural resistance. (It may be found in his book Testaments Betrayed.)

‘One Balzac’, Marx is supposed to have said, ‘is worth a hundred Zolas.’ Many of the writers discussed here have no ‘agenda’ of any sort, or are conservatives whose insight and integrity I have found indispensible. I remember for example sitting with Jorge Luis Borges in Buenos Aires, as he employed an almost Evelyn Waugh-like argument in excusing the military dictatorship that then held power in his country. But I had a feeling that he couldn’t keep up this pose, and not many years later he wrote a satirical poem ridiculing the Falklands/Malvinas adventure, while also making statements against the junta’s cruelty in the matter of the desaparecidos. It wasn’t just another author signing a letter about ‘human rights’; it was the ironic mind refusing the dictates of the literal one. And Borges, too, helped English evolve as a global idiom …

George Eliot is my Balzac in this instance. I spent a good deal of the 1990s attempting to understand the role played by lying and corruption and demagogy in American democracy. And here is Eliot in Romola, doing all my work for me in her depiction of fifteenth-century Florence:

There was still one resource open to Tito. He might have turned back, sought Baldassarre again, confessed everything to him – to Romola – to all the world. But he never thought of that. The repentance which cuts off all moorings to evil, demands something more than selfish fear. He had no sense that there was strength and safety in truth; the only strength he trusted to lay in his ingenuity and dissimulation. Now that the first shock, which had called up the traitorous signs of fear, was well past, he hoped to be prepared for all emergencies by cool deceit – and defensive armour …

He had simply chosen to make life easy to himself – to carry his human lot, if possible, in such a way that it should pinch him nowhere; and the choice had, at various times, landed him in unexpected positions. The question now was, not whether he should divide the common pressure of destiny with his suffering fellow-man; it was whether all the resources of lying would save him from being crushed by the consequences of that habitual choice.

Later – and this time on Savonarola and implicitly on all spiritual and secular authoritarians:

No man ever struggled to retain power over a mixed multitude without suffering vitiation; his standard must be their lower needs and not his own best insight.

Finally, and on all forms of totalitarian control, and the way in which they betray their supererogatory nature:

Looking at the printed confessions, she saw many sentences which bore the stamp of bungling fabrication: they had that emphasis and repetition in self-accusation which none but very low hypocrites use to their fellow-men.

(The last captures precisely the quality of hysterical falsity that led George Orwell to conclude, on literary evidence alone, that the admissions made at the Moscow show trials must have been sham.)

What might now be the tasks, or the opportunities, for the latent political intelligence of literature? The first, I suggest, is to find a language that can match the new world, or new cosmos, created for us by the Hubble telescope and the translation of DNA. We live at the opening of an age where the nature of humanity, and the nature of the universe, can at last be scrutinised and understood without racism or tribalism, and without superstition. (A page of Stephen Hawking on the ‘event horizon’ is more awe-inspiring than anything in Genesis or Ezekiel.) But we still employ the stilted and faltering metaphors of our pre-history; translating vivid new discourses back into the safe, solipsistic patois that we already know. Welcoming the completion of the Human Genome Project in the spring of 2000, President Clinton sounded like a gaping Elmer Gantry when he said it gave us the dictionary our Maker had used to ‘create’ us. At the present, then, language lags behind reality and behind humanity. Only a handful of authors (Martin Amis and Ian McEwan among them) have attempted to engage on this astonishing new terrain.

I have, finally, a wish for each of my countries. In post-Ukanian Britain, where the lineaments of a secular republic, or perhaps I should say federation of secular republics, are already emerging within the carapace of the ancien régime, we shall require something transcendent to replace the exhausted symbolism of the antique. My own semi-serious proposal is that we realign Westminster Abbey, deposing the ossuary of royalism from the centrepiece and re-naming the condescendingly titled ‘Poet’s Corner’. This would become, not a formal shrine, but a permanent witness to the greatness of English (and Irish and Scots and Welsh) literature. In Oliver Cromwell’s memorial cortège there walked John Milton, John Dryden and Andrew Marvell – a more splendid retinue than ever attended the obsequy of any monarch. Whereas the Queen Mother, introduced to the devoted royalist T. S. Eliot, could afterwards recall neither his name nor the title of the poem – she thought it might have been ‘The Desert’ – that he had read at Windsor Castle. There is an occluded republican tradition in our shared writing, of which Shelley along with Burns and Byron and many others are exemplars. It is time to make it explicit, and to teach it to the children (and, if you insist, to show it to the tourists).

In the case of the United States, we await a writer who can summon every nerve to cleanse the country of the filthy stain of the death penalty. Other priorities might seem at first to make larger claims, but there is probably no single change that would cumulatively amount to more than this one. Abolition would repudiate the heritage of racial bigotry and mob justice while simultaneously limiting the over-mighty state. Every argument of law and decency and precedent has already been skilfully made, against the gallows and the gas chamber and the firing squad and the immolating ‘chair’ and – arguably most obscene of all – the pseudo-medicalised ‘procedure’ of deadly injection. But there is as yet no Blake or Camus or Koestler to synthesise justice and reason with outrage; to compose the poem or novel – as did Herman Melville with flogging in his White-Jacket – that will constitute the needful moral legislation.

In the course of the decade past, I never even opened any of the books that purported to tell me of the postmodern death (or the relativism or collectivisation) of authorship. Superficial and ephemeral and sometimes sinister, this languid and onanistic tendency was, fortunately as well as inevitably, exhausted before it had begun. Instead, I read and re-read the writers who have allowed me to phrase these imperfect critiques and appreciations, and am grateful for the role they have let themselves play in my own inner life. Perhaps, with effort, we could begin to transcend the pessimistic definition of poetry that describes it as the element lost in translation.

Christopher HitchensWashington DC, July 2000

I

‘IN PRAISE OF …’

THE WILDE SIDE

GENEROSITY IS NOT the first quality that we associate with the name of Ms Dorothy Parker. But she did write the following rather resigned tribute and testament:

If, with the literate, I am

Impelled to try an epigram,

I never seek to take the credit;

We all assume that Oscar said it.

And so we do. ‘Work is the curse of the drinking classes.’ ‘He hasn’t a single redeeming vice.’ ‘I can resist anything except temptation.’ ‘He is old enough to know worse.’ It’s also worth bearing in mind the difference between an epigram and an aphorism. The former is merely a witty play on words (if one can use ‘merely’ in such a fashion), while the latter contains a point or moral. ‘Nothing is so dangerous as being too modern. One is apt to grow old-fashioned quite suddenly.’ In what press or public-relations office should that aphorism not be on prominent display?

Oscar Wilde’s weapon was paradox, and his secret was his seriousness. He was flippant about serious things, and serious about apparently trivial ones. ‘Conscience and cowardice are really the same things. Conscience is the trade-name of the firm.’ That could have been said by Hamlet, and was indeed uttered by him at much wearier length.

This year marks the centennial of Wilde’s greatest triumph and also of his ultimate disgrace. It was on Valentine’s Day 1895 that royal and aristocratic London was drawn in a body to see the opening night of The Importance of Being Earnest, one of the few faultless three-act plays ever written and certainly among the best-loved pieces of stagecraft in history.

But the moment of greatest adoration was also the occasion chosen by Nemesis. On that very opening night the Marquess of Queensberry, a thuggish aristocrat from the central casting of Victorian melodrama, made a scene at the stage door. Having failed to disrupt the performance, he left a bouquet of vegetables behind him and departed swearing vengeance on the man who was ‘corrupting’ his extremely corrupt son, Lord Alfred Douglas. So intense was Queensberry in his campaign of defamation that Wilde was led into the greatest mistake of his life – a suit for criminal libel to clear himself of the ‘gay’ smear, often known in the London homosexual underworld as the vice of being too ‘earnest’.

By the end of the year, which featured a trial (also in three acts) during which Wilde had the tables turned on him, the cowardly theatre manager had blotted out Wilde’s name from the play’s billboards (while continuing to take in record receipts), and Wilde himself was in the dock, indicted not only for committing what Victorians called ‘the abominable crime’ of sodomy but also for committing it with a member of the lower orders. Bankrupt, humiliated, deserted by his friends and his lover, weakened by illness and betrayal, he became the target for every sort of pelting and jeering and hissing, and was used as a sort of public urinal by a society seeking a vent for its hypocrisy and repression.

I recently made a pilgrimage to the grave of this great Irish rebel, who died in exile in Paris. On his deathbed he did certainly say that ‘I am dying beyond my means.’ He may or may not, on the other hand, have opened his eyes at the last, looked around the room, and murmured, ‘Either that wallpaper goes or I do.’

In Père Lachaise cemetery, among the sort of marble telephone booths favoured by the deceased French bourgeois, one searches for and finds the memorial carved by Jacob Epstein. It has been repeatedly smashed and defaced by philistines, and is the only monument in the whole place which displays a warning against vandalism. An attempted restoration in 1992 could not repair the damage done when some yahoo broke the genitalia off the statue. This lends unintentional point to the inscription on the plinth, which the vandal probably could not read:

And alien tears will fill for him

Pity’s long-broken urn,

For his mourners will be outcast men,

And outcasts always mourn.

We have a tendency to forget that the man who wrote the exquisitely light Importance of Being Earnest also wrote the unbearably laden Ballad of Reading Gaol.

Picking one’s way back to the graveyard gate, one cannot avoid the hundreds of young pilgrims who come, every day, to make a shrine out of the tomb of Jim Morrison. Poems, flowers, candles, scraps of clothing are heaped up to the memory of this lovely boy, cut off in full youth.

‘… I am true love, I fill

The hearts of boy and girl with mutual flame.’

Then sighing said the other, ‘Have thy will,

I am the love that dare not speak its name.’

These are the only lines for which Bosie will ever be remembered. Mutual flame. Come on, baby, light my fire.

Literature has an unpaid debt to Wilde, and so does philosophy. Take just one example of the former. As the curtain rises on The Importance of Being Earnest, we find a rich young bachelor in a fashionable London apartment, playing the piano. He imagines himself alone, and does not notice the butler. On seeing him, he utters the first words of the play:

ALGERNON: Did you hear what I was playing, Lane?

LANE: I didn’t think it polite to listen, sir.

Perfect. The action then moves to take in a tyrannical aunt (Lady Bracknell), an absurd romantic and matrimonial skein (Algernon and Jack and Gwendolen and Cecily) that is solved by a genealogical coincidence, a country house, a rural clergyman, a subplot involving a fortune, a happy ending. What do we have here if not the whole fantasy world of P. G. Wodehouse?

Wodehouse almost certainly saw the play as a young man, and went on to give us aunts and butlers and futile young men without ever mentioning Wilde even in passing. Wodehouse had a horror of homosexuality, it is true. But the whole of middle England placed Wilde under a ban for several decades, only occasionally reviving him as a writer of supposedly innocuous drawing-room farce.

The late Sir John Betjeman evokes the hushed conspiracy of silence in one of his early poems, ‘Narcissus’. A mystified small boy is told by his parents that he can no longer play with his dearest friend, Bobby:

My Mother wouldn’t tell me why she hated

The things we did, and why they pained her so.

She said a fate far worse than death awaited

People who did the things we didn’t know,

And then she said I was her precious child,

And once there was a man called Oscar Wilde.

Thus screwing him up for life.

What Wilde knew, and touched, went very deep into the psyche. That great critic Desmond MacCarthy once listed four of Wilde’s observations, in this order:

(i) As one reads history … one is absolutely sickened, not by the crimes that the wicked have committed, but by the punishments that the good have inflicted; and a community is infinitely more brutalised by the habitual employment of punishment, than it is by the occasional occurrence of crime.

(ii) Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.

(iii) Conscience must be merged in instinct before we become fine.

(iv) Nothing can cure the soul but the senses, just as nothing can cure the senses but the soul.

MacCarthy argued that half of Tolstoy’s philosophy is in the first quotation, and most of Yeats’s theory of artistic composition is contained in the second. Samuel Butler’s ethics are in the third quotation, and most of George Meredith’s philosophy of love is in the fourth. Hesketh Pearson added that if you read Wilde’s dictum ‘Every impulse that we strive to strangle broods in the mind, and poisons us’ you have imbibed the core doctrine of Sigmund Freud. (And I would add that when Algernon says, in The Importance of Being Earnest, ‘Really, if the lower orders don’t set us a good example, what on earth is the use of them? They seem, as a class, to have absolutely no sense of moral responsibility’, he anticipates Newt Gingrich, and the ‘welfare reformers’, by a clear century.)

Once heard, never forgotten. ‘A cynic is a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.’ This is not frothy phrasemaking, but serious wit. Not that Wilde scorned the throw-away line, even when it was risky. In the early days of his troubles with the law, he ran into an actor friend in Piccadilly and said angrily, ‘All is well. The working classes are with me … to a boy.’

Apart from one very scratchy disc made during his American tour, there are no recordings of Wilde in public or in private. But we have it on the authority of some of the great Victorian socialites and conversationalists that he was like this all the time. Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, who knew everybody and went everywhere and was one of the great poets of the decade, went to a ‘brilliant luncheon’ given by Margot Asquith and her husband shortly after their wedding. He could not keep the word ‘brilliant’ out of his diary entry: ‘Of all those present, and they were most of them brilliant talkers, he was without comparison the most brilliant, and in a perverse mood he chose to cross swords with one after the other of them, overpowering each in turn with his wit, and making special fun of Asquith, his host that day, who only a few months later, as Home Secretary, was prosecuting him.’

Yes, quite. There is a revenge that the bores and the bullies and the bigots exact on those who are too witty. Wilde could never hope to escape the judgement of the pompous and the hypocritical, because he could not help teasing them.

I personally find it hard, if not impossible, to read the record of his trial without fighting back tears. Here was a marvellous, gay, brave, and eloquent man, being gradually worn down by inexorable, plodding oafs and heavies. At first, Wilde had it all his own way, with laughter in the court. The grim, vindictive figure of Sir Edward Carson (later to take his Protestant rectitude into the incitement of a sectarian war in Ireland) was the grinding mill, with Wilde the leaping water:

‘Do you drink champagne yourself?’

‘Yes, iced champagne is a favourite drink of mine – strongly against my doctor’s orders.’

‘Never mind your doctor’s orders, sir.’

‘I never do.’

The brutish Carson later asked Wilde how long it took to walk from his Chelsea home to a certain other address:

‘I don’t know. I never walk.’

‘I suppose when you pay visits you always take a cab?’

‘Always.’

‘And if you visited, you would leave the cab outside?’

‘Yes, if it were a good cab.’

That was the last genuine laugh that Wilde got from the audience in court. Not long afterward, Carson, mentioning a certain servant boy, suddenly asked, ‘Did you kiss him?’ and Wilde incautiously replied, ‘Oh dear, no. He was a peculiarly plain boy.’ And that was that. Carson seized the whip handle, and never let go.

When he had done, Wilde was haggard and shaken and exposed. He managed one great moment of defiance from the box, in which he gave a ringing defence of ‘The Love That Dare Not Speak Its Name’. But the mill was now grinding in earnest, and he was trapped. At the close of the trial, the whores danced for joy in the streets, and mobs were spitting hatred, and dear Oscar was put to solitary work in a redbrick Victorian prison. An ear infection that went untreated by his jailers and an auction of his possessions held by gleeful creditors contributed to his death in penury five years later, at age forty-six. No morality tale could have had a more satisfying ending. There had never been such a victory for the bluenoses and the Pecksniffs since the public baiting of Lord Byron, about which Macaulay famously wrote, ‘We know no spectacle so ridiculous as the British public in one of its periodical fits of morality.’

It wasn’t only the British public that congratulated itself on the narrow escape from genius that it had undergone. Across the water in Germany, a sinister and twisted physician named Max Nordau had been at work on his book Degeneration. It was a powerful, if turgid, screed against what Nordau termed ‘Decadentism’ in the arts of painting, music, poetry, and sculpture. Nordau’s targets were Baudelaire, Swinburne, Zola, and Wilde – above all Wilde. He was not to be forgiven for his blasphemous pleasantries. Why, wrote Nordau splenetically, Wilde even spoke with disrespect of Nature! (‘All bad poetry springs from genuine feeling. To be natural is to be obvious, and to be obvious is to be inartistic.’)

Nordau strove constipatedly to establish a link between literary and aesthetic ‘degeneration’ and the sexual, social, and political kind. He was an orthodox dogmatist and authoritarian, who also spoke in the new language of eugenics about the ‘diseased’ and the ‘unfit’. George Bernard Shaw wrote an essay, entitled ‘The Sanity of Art’, defending Wilde and making fun of Nordau. And that might have been the last that was heard of him. Except that, after a debilitating war and a German defeat, the Nazi movement resurrected Nordau’s book and his theory of degeneration.

By the mid-1930s (and we are still talking about the lifetime of Lord Alfred Douglas), German museums and universities and galleries had been purged of the ‘decadent’, and artists of genius such as Otto Dix had their work confiscated and exhibited in a travelling show of ‘degenerate art’, where wholesome German families could safely come and jeer. Homosexual conduct, of course, had become punishable even by death. The philistines had really won this time, and were thoroughly enjoying themselves.

The good end happily, and the bad unhappily. That is what fiction means.

Wilde, who did not outlive the nineteenth century (he died in 1900), is nonetheless a uniquely modern figure. If it is safe to say that the work of writers such as P. G. Wodehouse and Evelyn Waugh and Ronald Firbank and Noël Coward is inconceivable without him, then it is safe to say that he is immortal. (Evelyn Waugh’s short story ‘Bella Fleace Gave a Party’ is lifted from a tale of Wilde’s.)

More recently, in his Eminent Domain, Richard Ellmann, acclaimed Wilde biographer, has argued that, ‘invited to dine with Oscar Wilde on Christmas day, 1888, [Yeats] consumed not only his portion of the turkey but all Wilde’s aesthetic system, which Wilde read to him from the proofs of The Decay of Lying. Once expropriated, this was developed and reunified in Yeats’s mind.’

So, rather like Gore Vidal in our time, Wilde was able to be mordant and witty because he was, deep down and on the surface, un homme sérieux. May his memory stay carnation-green. May he ever encourage us to think that the bores and the bullies and the literal minds need not always win. May he induce us to rise from our semi-recumbent postures.

First published as ‘The Wilde Side’ in Vanity Fair, May 1995

OSCAR WILDE’S SOCIALISM

IN CONVERSATION WITH Granville Barker, George Bernard Shaw once bragged that the comedy of his plays was the sugar that he employed to disguise the bitter socialist pill. How clever of the audience, replied Barker, to lick off the sugar and leave the bitter pill unswallowed. Of no play in the whole repertory of well-loved drama could this be more truly said than Oscar Wilde’s masterpiece in three acts, The Importance of Being Earnest. First performed in 1895, to applause that has never died away, it coincided with Wilde’s challenge to the infamous Marquess of Queensberry and with his decision to face his tormentors in court. That drama, which also fell into three acts (Wilde’s suit; Queensberry’s counter-attack; the prosecution of Wilde himself for immorality on the evidence of the first two trials) marked his utter eclipse and decline. In this centennial of Wilde’s triumph and ignominy, what can be done to honour his play as it should be honoured?

The Importance is so diverting and witty and fast-moving, and so replete with imperishable characters and mots, that it has been a staple of Anglo-American drawing-room comedy for generations. And, despite the cloud under which its author languished for so long (a cloud, as someone once observed, hardly bigger than a man’s hand) the play has been deemed fit for even the most demure school productions and amateur fiestas. It is a safe bet that Wilde would have appreciated the joke, because we know that he concealed at least one and – I would argue – probably two subtexts in his brittle dialogue.

The first subtext is of course a homosexual one. To be ‘earnest’ in Victorian London was to be gay in the slang of the underworld and the demi-monde (‘I hear he’s frightfully earnest’) so that one of the coded laughs at least was up in lights in the middle of the most ostensibly moral and bourgeois capital in history. But the game is deeper than that. The two young men who feature as the play’s central rivals, Jack Worthing and Algernon Moncrieff, are both portrayed as leading double lives, and as adopting alter egos, in order to pursue their true desires. The name Bloxham is used for a minor character, but those in the know would have recognised Jack Bloxham, editor of a high-risk homosexual aesthetic magazine to whom Wilde had promised Phrases and Philosophies For the Use of the Young (‘The first duty in life is to be as artificial as possible. What the second duty is no one has as yet discovered’). The magazine, which ran to exactly one edition, was suggestively entitled The Chameleon.

Other private or encoded jokes in the play range from the risqué and the nearly obvious (such as the tragedy of young men not turning out to resemble their mothers) to the argot of homosexual tradecraft. The practice of leading a secret life under a pseudonym, known as ‘Bunburying’, would have had some members of the audience hugging themselves with suppressed glee. ‘Cecily’, the name given to one of the weightless and vapid society girls, was also gay vernacular for transvestite rent-boys. Looked at in the right way, or played to the knowing ear, even the cloakroom at Victoria Station – scene of the loss of the famous handbag – takes on the charged association of a cruising spot or pick-up joint.

There was originally a fourth act to the play, in which Algernon was taken to Holloway Prison for failing to pay his bills at the Savoy. If that denouement had been retained, the coincidence between art and life would have been almost unbearable. Even as it is, the banter of The Importance does throw one shadow forward into the future. When Jack Worthing tells Canon Chasuble that his invented brother has died, and ‘seems to have expressed a desire to be buried in Paris’, the worthy Canon shakes his head and says: ‘In Paris! I fear that hardly points to any very serious state of mind at the last.’

The second of the two subtexts – the socialist one – is less fraught with ironies, and less apparent to superficial reviewers, but is in fact what gives the play its muscle and nerve. In The Soul of Man Under Socialism (which had to be published for a time as The Soul of Man in order to avoid objections from publishers and distributors) Wilde had subjected the bourgeois order to a merciless critique. In particular, he had shown the Victorian attitude towards marriage as an exercise in the mean-spirited preservation of private property, as well as a manifestation of sexual repression and hypocritical continence. In The Importance of Being Earnest, the same polemical objective is pursued, but by satirical means. Absurd and hilarious dialogues about betrothal, inheritance, marriage settlements, and financial dispositions are the very energy of the play. Everybody is supposed to marry for money and give up liberty; everybody is constrained to pretend that they are marrying for love or romance. ‘When I married Lord Bracknell,’ says Lady Bracknell, ‘I had no fortune of any kind. But I never dreamed for a moment of allowing that to stand in my way.’ It is, indeed, dear Lady Bracknell who continually gives the game away. When she hears that Cecily will inherit a hundred and thirty pounds she declares, ‘Miss Cardew seems to me a most attractive young lady, now that I look at her. Few girls of the present day have any of the really solid qualities, any of the qualities that last, and improve with time.’

Her instinctive class consciousness makes her the arbiter of every scene. Inquiring of Jack the suitor whether he has any politics, and receiving the answer that ‘I am afraid I really have none. I am a Liberal Unionist,’ she ripostes, ‘Oh, they count as Tories. They dine with us. Or come in the evening at any rate.’ Pressing him further on his eligibility and inquiring as to whether his money is in land or investments, she is told, ‘Investments, chiefly’, and muses aloud:

That is satisfactory. What between the duties expected of one during one’s lifetime, and the duties exacted from one after one’s death, land has ceased to be either a profit or a pleasure. It gives one position, and prevents one from keeping it up.

This more or less precisely describes the dilemma of the English aristocracy when faced with the Industrial Revolution, and captures it more neatly than Engels ever managed to. Indeed, one expert on this period, Frances Banks, has argued convincingly that much of the play is also a satire on the Cecil dynasty, whose scion, Robert Marquess of Salisbury, was three times a Tory prime minister in the late Victorian epoch. His biographer was his daughter, Lady Gwendolen Cecil. The two girls in the play are named Gwendolen and Cecily. The Salisbury family motto, just for good measure, is Sero Sed Serio: ‘Late but in earnest’. And the great family estates were linked to London by a network of those railways in which the landed classes took such an early and profitable interest. In every scene of The Importance of Being Earnest there is at least one joke about the railways, with a repeated play on words, that depends for its effect on the echoes of ‘line’ and ‘lineage’.

There is little if any strain involved in making these conjectures, because we know that Wilde read the literature of socialism, attended meetings, and kept company with leading socialists such as Shaw (who didn’t like The Importance, typically regarding it as frothy). Wilde was the only public figure in London to sign Shaw’s petition about the Haymarket martyrs. He took an active interest in the rising labour movement, and in the work of William Morris and other leading critics of capitalist utilitarianism. The kernel of his credo, however, is to be found in the offhand remark made by Algernon Moncrieff at the opening of The Importance, where he reflects, ‘Really, if the lower orders don’t set us a good example, what on earth is the use of them? They seem, as a class, to have absolutely no sense of moral responsibility.’ Here, in a well-turned aside, is the cruelty and thoughtlessness of all theorising about the deserving rather than the undeserving poor. Wilde never lost his revulsion against sermonising of this kind, and maintained that it was finer to steal rather than to beg; just as it was morally deaf to preach strict dieting to those suffering from malnutrition. It was for guessing at the secret hatred and coldness, which at all times underlay the English profession of charity and moral hygiene, that he made the enemies who rejoiced in his abjection.

Britain was at the time engaged in a grim, self-righteous attempt to hold on to its oldest colony in Ireland. British secret police circles were later to use the weapons of blackmail and moral exposure to destroy two of the bravest spokesmen for Irish independence – Charles Stewart Parnell and Sir Roger Casement. It’s unlikely that Wilde’s mordant observations about the Empire’s treatment of his homeland would have escaped the attention of the prurient. In a tremendously prescient review in the Pall Mall Gazette in 1889, he saw precisely why England’s hold on Ireland would weaken:

If in the last century she tried to govern Ireland with an insolence that was intensified by race hatred and religious prejudice, she has sought to rule her in this century with a stupidity that is aggravated by good intentions … An entirely new factor has appeared in the social development of the country, and this factor is the Irish-American and his influence. To mature its power, to concentrate its actions, to learn the secrets of its own strength and of England’s weakness, the Celtic intellect has had to cross the Atlantic. At home it had but learned the pathetic weakness of nationality; in a strange land it realised what indomitable forces nationality possesses. What captivity was to the Jews, exile has been to the Irish. America and American influence has educated them.

Though this review, too, contained some instances of Wilde at his most aphoristic (‘That the government should enforce iniquity and the governed submit to it, seems to Mr Froude, as it certainly is to many others, the true ideal of political science. Like most penmen he overrates the power of the sword’), it demonstrates that he could dispose also of a solid and grounded political intelligence. Within a few years of Wilde’s death, the American citizen Eamon de Valera had in effect out-generaled the British Empire. Only this year came yells of anguish from the British Tories as a Republican guerrilla was greeted on the White House lawn, and London (which believed itself to have an exclusive ‘special relationship’ with the American Empire) gnashed impotently at this reminder of blood debts incurred decades before.

In a similar vein, Wilde reviewed the poems that Wilfred Scawen Blunt published from prison, and announced that the self-righteous Tory ‘intellectual’ Arthur Balfour had, if nothing else, improved Blunt’s style and address as a poet by committing him to jail for his agitation upon the Irish question. Wilde’s banter at Balfour’s expense was exactly designed to be of the sort that would land him in trouble – Blunt himself noticed the same tendency at a lunch for Herbert and Margot Asquith, when Wilde teased the entire assembly of the Establishment and won every round – but at least this serves to correct the later picture of Wilde as an epicene dandy whose sallies were confined to the lounge. ‘Literature is not much indebted to Mr Balfour for his sophistical Defence of Philosophic Doubt, which is one of the dullest books we know, but it must be admitted that by sending Mr Blunt to jail he has converted a clever rhymer into an earnest and deep-thinking poet.’ The intention of Balfour and his class, by committing Wilde to jail, was to achieve something like the opposite effect. (Just to increase the frisson, it’s worth noting that Blunt’s volume of poems was entitled In Vinculis, later to be the subtitle of Wilde’s own prison testimony De Profundis.)

We can therefore situate Wilde firmly in the company of the Victorian socialist aristocracy; a radical élite, contemporary with Marx himself, which wrote and acted with great distinction. Its contribution has largely been forgotten, because as George Dangerfield so hauntingly records in his book The Strange Death of Liberal England, it was overwhelmed by the First World War that it tried so hard to prevent. I’ve already mentioned William Morris, who is remembered still as a Pre-Raphaelite and aesthete rather than as an orator and polemicist. Wilde’s set also included Blunt, who probably did more than any other single author for the emancipation of the colonies, and who is an honoured figure today in Egypt, India, Ireland, and other former precincts of the Empire on which the sun never set (and on which, as the Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor once remarked, the blood never dried).

One might also mention R. B. Cunninghame-Graham, the friend and inspiration to Joseph Conrad, who rounded off a whole career of travel and writing and anti-imperialist adventure by getting himself elected as the first explicitly socialist member of the House of Commons. In the late Victorian and Edwardian periods, men like this fought to build up an educated labour movement, to win independence for Ireland, and to advance and guarantee the rights of women. The terrible year of 1914, and the attendant capitulation of the Socialist International, put an end to what had been one of the most revolutionary and democratic periods in modern history. From then on, the choice would be made between official and routine Labourism and the disciplined apparatus of Leninism and its mutations. Imperialist war – the outcome of an ostensibly ‘liberal’ imperium – had very nearly returned civilised Europe to a barbaric state. This does not entitle us to forget a more noble and defeated tradition, in which Wilde, among others, took an honourable place.

I am not employing the terms ‘aristocracy’ or ‘noble’ by accident. In all of Wilde’s radical writing there is an unashamed belief that those who suffer or dare for freedom are a kind of elect – not the insipid and overbred aristocracy of wealth and property that he lampooned, but an elect nonetheless. Though he was skeptical of organised religion and in most conscious moments considered himself a Hellenist, he employed biblical and prophetic imagery to mark off martyr from mob. Richard Ellmann points out very deftly the ambivalence of his Sonnet to Liberty, in which he expressed distaste for those whose anger rose from mere resentment:

Not that I love thy children, whose dull eyes

See nothing save their own unlovely woe,

Whose minds know nothing, nothing care to know –

Yet at the close of the poem, Wilde also distinguishes himself from the Lady Bracknell types who talked selfishly about the ‘worst excesses of the French Revolution’ and predicted that education for the poor would ‘lead to acts of violence in Grosvenor Square’:

… and yet, and yet,

those Christs that die upon the barricades,

God knows it I am with them, in some things.

Elements of this tension are apparent in Wilde’s play Vera, or The Nihilists, in which he foreshadowed the coming Russian revolution. He was always to be upset and disillusioned by the failure of this play, which was based upon the true story of Vera Zasulich, a proto-Bolshevik woman who assassinated the St Petersburg chief of police in January 1878. (This action led to a feverish discussion among the anti-tsarist forces about the morality and efficacy of ‘individual terrorism’, partly because the assassination proved both popular and effective.) And Wilde was a personal friend of another Russian revolutionary, Sergei Kravchinski, who had also shot a tsarist torturer and who lived as a well-liked emigré in London circles. Drawing on Bakunin and Nechayev’s Revolutionary Catechism, and on his reading of Dostoyevsky and Turgenev, Wilde fashioned a play about propaganda by deed. The hero is beyond doubt Prince Paul Maraloffski, who falls out with the czar and joins the revolutionary conspirators. ‘In a good democracy,’ opines this prince at one crucial moment, ‘every man should be an aristocrat.’

This addiction to paradox, which was always his most penetrating method in any case, led Wilde to state at the opening of The Soul of Man Under Socialism that socialism’s great benefit would be the abolition of that ‘sordid necessity of living for others’ that was everywhere so oppressive. The effect of this rather flippant-seeming introduction was to peel the whiskers from the face of Church and State, which had bound every citizen into a nexus of obligation and guilt. For Wilde, all talk of ‘the masses’ and ‘the people’ was suspect, because these categories were made up of individuals and it was the free development of each individual that counted. He occupied a position somewhere between Karl Marx and William Morris; between the idea that labour was something to be transcended and the idea that it was something to be made artistic and enjoyable. Under no circumstances should socialism become the brute collectivisation of existing drudgeries. In an 1889 review of Edward Carpenter’s socialist songbook Chants of Labour, Wilde wrote that

Socialism is not going to allow herself to be tramelled by any hard and fast creed or to be stereotyped into an iron formula. She welcomes many and multiform natures. She rejects none and has room for all. She has the attraction of a wonderful personality and touches the heart of one and the brain of another, and draws this man by his hatred of injustice, and his neighbour by his faith in the future, and a third, it may be, by his love of art or by his wild worship of a lost and buried past. And all of this is well. For to make men Socialists is nothing, but to make Socialism human is a great thing.

This was written a hundred years before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Much of it was a statement of desire rather than belief in any case, and later sections of the review betray some misgivings. Of many of the proletarian anthems, Wilde wrote that ‘almost any mob could warble them with ease’. Approving Edward Carpenter’s sentiment, which was common in those brave radical days, that the masses did indeed have an appreciation of beauty and finesse, he closed by saying:

The Reformation gained much from the use of popular hymn-tunes, and the Socialists determined to gain by similar means a similar hold upon the people. However, they must not be too sanguine about the result. The walls of Thebes rose up to the sound of music, and Thebes was a very dull city indeed.

It cannot be mistaken to see in this and other Wildean observations a coded plea for the right to live as a sexual outlaw, an eternal dissident and an enemy of the regimented, the ‘healthy’, and the ‘natural’. It was this set of affinities, indeed, which involved Wilde in almost his last polemical battle; one that was to reverberate long after his death.

In 1892 the German author Max Nordau published his book Entartung; which translates either as ‘Degeneracy’ or ‘Degeneration’. It was a stern and somewhat dirty-minded philippic against those who led unwholesome lives or professed admiration for unnatural philosophies. The volume was dedicated to Cesare Lombroso, pioneer of racist phrenology and coiner of the pseudo-science of the ‘criminal type’. It exuded admiration for racial strength, nature-worship, orthodox manliness, and artistic convention. In identifying the sources of that degeneracy that was sapping the vital fluids of civilisation Nordau made a prime exhibit of Wilde. Claims of genius were merely neurotic, said Nordau, and homosexuality was the greatest degeneracy of all. Wilde, who was by this time being hideously maltreated in an English prison, attempted a feeble defence by pleading that if homosexuality was an illness it should not be punishable but treatable – a sad hostage to fortune. Recovering a little of his old form after his release, he said, ‘I quite agree with Dr Nordau’s assertion that all men of genius are insane, but Dr Nordau forgets that all sane people are idiots.’ Bernard Shaw wrote a riposte to Nordau, staunchly maintaining that here in a new and more virulent form was the traditional superstition that the stock was weakening and civilisation going to the dogs. (Given Shaw’s own interest in eugenics, that was quite a strong reply.)

Two historical ironies arise from this little-remembered combat. Max Nordau was, with Theodor Herzl, one of the founders of political Zionism. To this day, the supporters of the ultra-Orthodox and ultranationalist forces in Israel refer to assimilated or secular Jews as ‘Hellenised’ – the worst insult in their lexicon, and one that might have called forth a sympathetic smile from Wilde. Second, Nordau’s Jewishness and Zionism did not prevent the resuscitation of his book by the Nazis after Germany’s defeat in the First World War. ‘Degeneration’ became the summary word for everything – cosmopolitan, Mediterranean, skeptical – that the New Order regarded as weak or treacherous in the German character. Those who have visited the exhibitions of Entartete Kunst (‘Degenerate Art’) put on by the Nazis will see the force of the campaign that listed ‘pacifism’ and antimilitarism along with mental illness, physical deformity, and the mockery of religion as enemies of the state. A parallel exhibition, entitled Entartete Musik, had as its poster and advertisement a thick-lipped Negro blowing into a saxophone and displaying a Star of David on his lapel.

Wilde’s misgivings about socialism – that it would prove humourless, uniform, and hostile to the untamed and the emotional and aesthetic – were to be fully materialised in National Socialism. He might have wished to protest that this was taking the business of paradox too far.

First published as ‘Oscar Wilde’s Socialism’ in Dissent, Fall 1995

LORD TROUBLE

IN BERLIN IN 1892, Max Nordau published his extraordinary book Entartung, or ‘Degeneration’. Dedicated to the pseudo-scientist and (let me risk a tautology) phrenologist Cesare Lombroso, this dense and lengthy diatribe sought to lay bare the origins and effects of national and individual self-hatred and self-destructiveness. Directed at the languor and amorality of what Nordau was already terming the ‘fin de siècle’, it exalted the ‘normal’, the ‘manly’, and the utilitarian over the neurotic and the aesthete. Herr Nordau had some unresolved difficulties of his own – he had changed his name from Südfeld or ‘Southern Field’ to the more bracing and valiant-sounding ‘Northern Meadow’ – and he was the most militant deputy of Theodor Herzl in proposing a Zionist solution to the Luftmensch question, the nagging problem of the enfeebled and deracinated and feminised Jew. (The fact that the National Socialists later borrowed his book and his concept, and staged taunting exhibitions of