11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

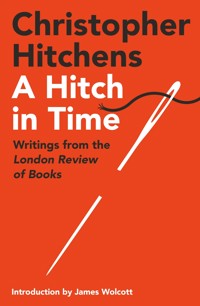

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

'Revisiting this selection of diaries and essay-reviews from the London Review of Books is restorative, an extended spa treatment that stretches tired brains and unkinks the usual habitual responses where Hitchens is concerned.' James Wolcott in his introduction Christopher Hitchens was a star writer wherever he wrote, and the same was true of the London Review of Books, to which he contributed sixty pieces over two decades. Anthologised here for the first time, this selection of his finest LRB reviews, diaries and essays (along with a smattering of ferocious letters) finds Hitchens at his very best. Familiar bêtes noires - Kennedy, Nixon, Kissinger, Clinton - rub shoulders with lesser-known preoccupations: P.G. Wodehouse, Princess Margaret and, magisterially, Isaiah Berlin. Here is Hitchens on the (first) Gulf War and the 'Salman Rushdie Acid Test', on being spanked by Mrs Thatcher in the House of Lords and taking his son to the Oscars, on America's homegrown Nazis and 'Acts of Violence in Grosvenor Square' in 1968. Edited by the London Review of Books, with an introduction by James Wolcott, this collection recaptures, ten years after his death, 'a Hitch in time': barnstorming, cauterising, and ultimately uncontainable.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

A HITCH IN TIME

ALSO BY CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS

BOOKS

Hostage to History: Cyprus from the Ottomans to Kissinger

Blood, Class, and Nostalgia: Anglo-American Ironies

Imperial Spoils: The Curious Case of the Elgin Marbles

Why Orwell Matters

No One Left to Lie To: The Triangulations of William Jefferson Clinton

Letters to a Young Contrarian

The Trial of Henry Kissinger

Thomas Jefferson: Author of America

Thomas Paine’s ‘Rights of Man’: A Biography

God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything

The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever

Hitch-22: A Memoir

Mortality

PAMPHLETS

Karl Marx and the Paris Commune

The Monarchy: A Critique of Britain’s Favourite Fetish

The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice

A Long Short War: The Postponed Liberation of Iraq

ESSAYS

Prepared for the Worst: Selected Essays and Minority Reports

For the Sake of Argument: Essays and Minority Reports

Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere

Love, Poverty and War: Journeys and Essays

Arguably: Essays

And Yet…: Essays

COLLABORATIONS

Callaghan: The Road to Number Ten (with Peter Kellner)

Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question(with Edward Said)

When the Borders Bleed: The Struggle of the Kurds (photographs by Ed Kashi)International Territory: The United Nations, 1945–95 (photographs by Adam Bartos)

Vanity Fair’s Hollywood (with Graydon Carter and David Friend)

Left Hooks, Right Crosses: A Decade of Political Writing(edited with Christopher Caldwell)

Is Christianity Good for the World? (with Douglas Wilson)

Hitchens vs. Blair: The Munk Debate on Religion (edited by Rudyard Griffiths)

A Hitch in Time

Writings from the London Review of Books

Christopher Hitchens

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Christopher Hitchens, 2021

Introduction copyright © James Wolcott, 2021

The moral right of Christopher Hitchens to be identified as the authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All pieces previously published in the London Review of Books.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by anymeans, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording,or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyrightowner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from theBritish Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-83895-600-4

E-book ISBN: 978-1-83895-601-1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House, 26–27 Boswell Street, London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Set in FF Quadraat

CONTENTS

Introduction by James Wolcott

The Wrong Stuff: On Tom Wolfe, 1983

Diary: Operation Desert Storm, 1991

Oh, Lionel! On P.G. Wodehouse, 1992

Mary, Mary: On J. Edgar Hoover, 1993

Say what you will about Harold: On Harold Wilson, 1993

Diary: The Salman Rushdie Acid Test, 1994

Diary: Spanking, 1994

Who Runs Britain? Police Espionage, 1994

Lucky Kim: On Kim Philby, 1995

Diary: At the Oscars, 1995

Look over your shoulder: The Oklahoma Bombing, 1995

Letters: Richard Cummings, Christopher Hitchens

After-Time: On Gore Vidal, 1995

A Hard Dog to Keep on the Porch: On Bill Clinton, 1996

The Trouble with HRH: On Princess Margaret, 1997

Brief Shining Moments: Kennedy and Nixon, 1998

Letters: Arthur Schlesinger Jr, Christopher Hitchens, Mervyn Jones

Acts of Violence in Grosvenor Square: On 1968, 1998

Diary: The ‘Almanach de Gotha’, 1998

Moderation or Death: On Isaiah Berlin, 1998

Letters: Roger Scruton, Francis Wheen, Mark Lilly, Christopher Hitchens

What a Lot of Parties: On Diana Mosley

11 September 1973: Pinochet and Britain

Index

Introduction

James Wolcott

IRECALL vividly my first beholding of the Christopher Hitchens Experience, one of those epiphany moments that drops into your lap unbidden. The occasion was Vanity Fair’s holiday party for staff and contributors, the venue that year being Joe’s Pub, a restaurant and performance space. Magazine holiday parties traditionally tended to be brisk, collegiate affairs held in the office after a regular workday, consisting of a judiciously sipped drink or two, a few flurries of flirtation here and there, and a bit of ‘face time’ with the editor in chief before a discreet getaway, the streets thronged with other early evacuees desperately trying to flag a taxi in those pre-Uber times. Not Vanity Fair’s. Vanity Fair holiday parties, like the magazine itself in those ad-flush days, laid on the bezazz. They were what parties were meant to be, beehive buzzfests building in noise and body English until the floorboards seemed to bounce. Spilled drinks, shards of laughter, impetuous doings in the bathrooms. And this party was even more boisterous than its predecessors. One editorial assistant had to be lofted and carried out like a fallen comrade. The whole evening had a theatrical oomph as a DJ kept everything in throbby motion. All that was missing was a disco ball.

And then, on the Joe’s Pub stage, like an Avengers’ portal opening from another dimension, materialised editor Graydon Carter and star columnist Christopher Hitchens, embracing the tribal spirit and grooving away to the thudding beat. Others were on stage as well, but all eyes still capable of focusing trained on the dynamic duo. They weren’t dancing with each other so much as at each other, loosely mirroring each other like friendly tugboats, and at one point Hitchens whipped off his jacket with toreador flair to whooping cries of encouragement. He undid a button of his white shirt or perhaps it popped on its own and chugged towards Carter, attempting to bump bellies. Graydon retreated a few steps, protecting his front. It was one thing for the editor in chief to electric boogaloo, but bumping bellies was a bridge too far. Decorum must be maintained even in the midst of bacchanal. Yet Hitchens persisted, his belly declining to take no for an answer, this sweaty pagan spectacle unfolding before our eyes until it looked as if he might strip off his shirt entirely and cast it aside like a Chippendales dancer. ‘My God,’ I thought, ‘the legends are true. Dionysus rides again!’ Then the portal resealed and the vision dissolved, or maybe the music just stopped, and into the night we trooped, with much to talk about the next day.

For years Hitchens and I shared Vanity Fair’s front of the book as monthly columnists, nobly pulling our load. Our shoulder-rubbing adjacency in print led to occasions of misidentity. More than once I was complimented on a coruscating piece that had been Hitchens’s handiwork. ‘That was ballsy of you to get water-boarded,’ a stranger on the bus leaned over to confide one afternoon, leaning back after I informed him, ‘That wasn’t me, that was Hitchens.’ Similarly, I was once consoled on the Brazilian bikini wax I had so sportingly undergone for the purposes of participatory journalism. Again, Hitchens. Despite our sharing the same real estate in VF’s glossy pages and being mistaken for each other by random civilians, we had almost no personal overlap or exchanges, apart from the seasonal holiday bacchanals or the occasional book party. He was based in Washington DC, his residence the nearest thing the Potomac had to a brainy salon (it was also the site of Vanity Fair’s gala White House Correspondents Dinner after-party, whose guests one year included Salman Rushdie, Olivia Wilde and Tucker Carlson); I called Manhattan home. He was peripatetic, a roving correspondent who filed reports from the Middle East and even North Korea; me, not. We stayed in our separate lanes, his lane far more spacious and trafficked than mine. Unlike so many others, then, I have no picnic basket of personal anecdotes to unpack, no intimate exchanges. In conversation with others I never referred to him as Christopher or Hitch; that would have presumed a familiarity I didn’t possess.

Had we been able or inclined to spend time in each other’s company, I would have been at a disadvantage, my capacity for alcohol being far below that of the average debutante’s. One drink and I begin to stare out at sea, looking for white sails. Many others did their valiant, futile best to keep up with his industrial quota. After Hitchens’s much mourned death in 2011, the last stanza in his gruelling, unflinching, heroic battle with oesophageal cancer (documented in his posthumous memoir, Mortality), one personal tribute after another related how the subject and mentor spent hours talking and drinking into blue midnight, the narrator reduced to a woozy heap as Hitchens padded off to his keyboard and batted out a ream of copy that was witty, informed, sardonic and rounded off, as glistening and pristine as a Richard Avedon contact sheet. No matter how high the evening’s intake, one pavilion of Hitchens’s brain remained brightly lit and open for business.

In the autumnal fullness of time, Hitchens’s prodigious amount of alcoholic input and journalistic output, the lubricated churn of his powerhouse intellect and his unflagging stamina, the barnstorming pace of all those panels, speeches, debates, and TV appearances, seemed to defy the laws of human biology. How did he not implode? Plus, he smoked. The premier action shot of Hitchens at the crest of his public notoriety would show him steaming up to the auditorium lectern with a glass in one hand and a cigarette in the other, the last of the living-large, two-fisted provocateurs, ready to conquer ideological foes and hecklers alike as a lick of hair flopped over his forehead like Elvis Presley. He could be droll one moment, cauterising the next, thunder-rumbling as he reached a peroration, an old-school duellist and rhetorician like we ain’t got much of in Amurrica. In his adopted country (he became a US citizen in 2007), Hitchens’s methodical glee in flustering everyone’s preened feathers provided welcome relief from the fraternal order of technocratic weenies, Beltway insiders, meritocratic humbugs and conventional-wisdom recyclers who plagued us then (and are even more prevalent today – another swamp Trump failed to drain), but his roguish image often overshadowed the actual writing, especially with the rise of social media, which tends to caricature everything and everyone into a meme or a jokey gif, catering to the twitchy eyeballs of the attention-deficited and sleep-deprived.

So revisiting this selection of pieces from the London Review of Books, none of which has been anthologised before in his other essay collections, is restorative: an extended spa treatment that stretches tired brains and unkinks the habitual responses where Hitchens is concerned. Tonic too are the fencing matches in the letters printed after a few of the pieces. In one exchange he makes mincemeat of the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr over the schmaltz that was Camelot. Writers weren’t reluctant to rumble then. For some, the punchy effect may be almost prelapsarian. The reviews run from the year 1983 until, significantly, 2002, a key demarcation line in the Hitchens chronology. That was the year Hitchens resigned as a columnist on the Nation (where he had alternated with fellow expat Alexander Cockburn), over the magazine’s opposition to the proposed invasion of Iraq, which Hitchens full-throatedly championed, to the anger and dismay of his dovish comrades and disciples (in 2003, Hitchens and his book-length tribute to Orwell were on the receiving end of an air-land-and-sea assault by Stefan Collini in the LRB entitled ‘“No Bullshit” Bullshit’, indicative of how bitter the breach had been). Hitchens’s war stance amounted to quite a pivot from his past. Here he is in the second piece in this collection, a diary about the (first) Gulf War: ‘There were a thousand ways for a superpower to avert war with a mediocre local despotism without losing face. But the syllogisms of power don’t correspond very exactly to reason.’ George Packer, author of The Assassins’ Gate: America in Iraq, later attempted to account for this abrupt turn from militant gadfly to taloned hawk:

He was, by his own lights and that of his admirers, a thoroughgoing contrarian. (One of his lesser-known books was called Letters to a Young Contrarian.) And nothing could be more contrarian, in the early years of the last decade, than for a hero of the left to embrace George W. Bush. It breathed new life into Hitchens, his persona and his prose.

A snootful of dragon fire, more like. The evening sky crimsoned from all the bridges he burned. Before the decade was over Hitchens would break with former friends and allies such as Cockburn, Harold Pinter, Edward Said and his eminence Gore Vidal (the review of Palimpsest in these pages emanates a fond regard that would be dashed during their bitter divorce), while annexing a new audience and further expanding his army of admirers and detractors with the rousing success of his Menckenesque diatribe God Is Not Great (2007), which elevated him into perhaps the most formidable gladiator for what was then called the New Atheism. His bestselling memoir Hitch-22 (2010) further bronzed his foxy, avuncular status as public entertainer/public intellectual. Everything would have been fine if only, if only. But blood is a difficult stain to remove, and the tragic debacle that resulted from the botched occupation of Iraq, coupled with Hitchens’s chummy relationship with some of the chief architects of that horror (particularly Bush’s deputy secretary of defence, Paul Wolfowitz), continues to discolour the legacy of Hitchens 2.0. This mottled legacy will give biographers (at least one biography is in the works) and memoirists much to mull over and grapple with, so let us leave them to their mulling and grappling while we crack open this jewellery case.

When it comes to English prose, Hitchens wrote as he spoke, an offhand eloquence that seemed to roll off the wrists, conscripting the listener-reader into his confidences to the melodic clink of ice cubes in the clubby background. His classic, roguish, cant-defoliating English style, an inheritance from Hazlitt and similar bravehearts, is fortified by an armoury of deep reading and lucid recall, wide acquaintanceship (which translates over time into an abundance of sources), and a close proximity to many of the major players of the day as they promenaded across the stage or, in the case of his friend Salman Rushdie, hid for their lives. In a diary published after the fifth anniversary of the fatwa against the novelist over The Satanic Verses, the following parenthetical surfaces like a soap bubble:

(In a rather mad piece in the New Yorker, Cynthia Ozick compared Rushdie to ‘a little Israel’, surrounded as he was by ravening Muslim wolves, and also remarked on the evident expansion of his waistline since the last time she saw him in public. Ms Ozick, as it happens, is rather keen on the expansion of the Israeli midriff as it extends over the once slimline waist to engross the Occupied Territories. So the comparison was a doubly tactless one . . .)

In ‘On Spanking’, Hitchens recalls the blushing thrill of being disciplined by Margaret Thatcher for being a saucy boy (a smack across the bottom with ‘a rolled-up parliamentary order paper’, presumably no copy of the Spectator being nearer to hand) as the springboard to a larger inquiry into the upper class’s craving for bent-over supplication:

In the great rolling growl that used to sweep Tory Party Conferences at any mention of the birch, there could be detected a thwarted yearning to have everybody under control again: back in school, with its weird hierarchy of privileges and sufferings; back in the ranks of the regiment where a good colour sergeant could keep them in order; back in the workhouse and under the whip of the beadle. If this means a population that is somewhat infantilised and humiliated, well how else can you expect to get people to wait in the rain to see a royal princess break a bottle of cider over the bows of a nuclear submarine?

Now there are newer, easier, less inclement ways to infantilise a nation, but enough about Love Island.

For writers attuned to the follies of their day, every fleeting encounter presents a possible frisson. That Princess Margaret, for example, she sure got around:

If you were a commoner of average social mobility in London in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, there was a better than average chance that you would have met her in some club or at some party, or even on the pavement outside. Martin Amis remembers her showing up at the end of a dinner, on the arm of Nicholas Soames, and seating herself at the piano to sing ‘My Old Man’s a Dustman’ (to which, of course, the only answer was ‘No he ain’t’).

In an review of a biography of Diana Mosley, one of the most over-doted-on ivory swans in the unsavoury annals of the 20th century, Hitchens asides:

I once spent some time with Sir Oswald Mosley, in a television green room. He chatted amiably enough, reminiscing away and turning on the charm, and recalling . . . that the most disconcerting disruption of any of his speeches took place in Oxford, when some pinko students simply opened newspapers in the front row of the hall and read them calmly throughout his rantings. Then he got on the set, adjusted his mike, set his jaw and delivered (this was 1972) a hideous attack on the arrival of Ugandan Asian refugees.

Off came the mask of gentility, out jutted the gargoyle.

Never a writer to shirk a challenge, no matter how much tedium it threatened, Hitchens manages to perform feats of levitation on the seemingly inert bulk of a biography of the former prime minister Harold Wilson, and does his valiant best to cut through the thick, overcooked spinach of pseudo-historical, mytho-hooga-booga of Cold War spy lore, arriving with a fed-up frustration with these ‘endless quasi-disclosures and planted rigamaroles.’ New to me, the magisterial essay on Michael Ignatieff’s biography of Isaiah Berlin is like moving into an ivy-draped mansion, tastefully apportioned and strewn with mirrors that begin to give you the willies. Nothing written on the author of Russian Thinkers, Against the Current and the worn-to-nub distinction between The Hedgehog and the Fox has so painstakingly delineated the performative nature of Berlin’s bony, beleaguered donnish toga-modelling: ‘the combined ingratiation and self-pity no less than the assumed and bogus late Roman stoicism.’ The veneration of Berlin into the supreme stately ambassador for the life of the mind obscured the Lionel Trilling-ish qualms, equivocations and vacillations eating away inside the polymath. Hitchens:

I propose that Berlin was somewhat haunted, all of his life, by the need to please and conciliate others; a need which in some people is base but which also happened to engage his most attractive and ebullient talents. I further propose that he sometimes felt or saw the need to be courageous, but usually – oh dear – at just the same moment that he remembered an urgent appointment elsewhere.

The torrential commentary and interview palaver that gushed from Berlin’s spout produced an impressive din that sounded swell but didn’t add up to much. ‘If it is fair to say, as Ignatieff does, that Berlin never coined an epigram or aphorism, it is also fair to add that he never broke any really original ground in the field of ideas. He was a skilled ventriloquist for other thinkers.’ Yet the essay isn’t a hit job, tipping a marble bust from its plinth for a satisfactory crash. It’s a true revaluation, an antidote to the hagiographical aura that still persists.

Hagiography will never attach to Hitchens, no matter how much hero worship he still inspires from fellow thespians of the written word (see Martin Amis’s valedictory Inside Story, an ode to male friendship where the voice seemed to crack). Hitchens generated buffetings of turbulence his entire career and the air of contention has yet to subside. This is for the best. Few things sink a reputation in posterity as irretrievably as a well-formed consensus that functions like embalming fluid, leaving behind a waxy, respectable relic, and there’s no danger of that with Hitchens. Even in death he remains uncontainable.

_______________________________________

Fax from Christopher Hitchens to Mary-Kay Wilmers, 12 May 1996. ‘Rupert’ is Rupert Murdoch.

The Wrong Stuff

On Tom Wolfe

1983

HERE, for a start, are some nuggets of the old and the new New Journalism. What do they have in common?

By now, 1967, with more than a hundred combat missions behind him, Dowd existed in a mental atmosphere that was very nearly mystical. Pilots who had survived that many games of high-low over North Vietnam were like the preacher in Moby-Dick who ascends to the pulpit on a rope ladder and then pulls the ladder up behind him.

‘The Truest Sport: Jousting with Sam and Charlie’

It is entirely possible that in the long run historians will regard the entire New Left experience as not so much a political as a religious episode wrapped in semi-military gear and guerrilla talk.

‘The “Me” Decade and the Third Great Awakening’

The reception of Gropius and his confrères was like a certain stock scene from the jungle movies of that period. Bruce Cabot and Myrna Loy make a crash landing in the jungle and crawl out of the wreckage in their Abercrombie & Fitch white safari blouses and tan gabardine jodhpurs and stagger into a clearing. They are surrounded by savages with bones through their noses – who immediately bow down and prostrate themselves and commence a strange moaning chant:

The White Gods!

Come from the skies at last!

From Bauhaus to Our House

In the margin of the first extract, one might simply write: no they weren’t. In the margin of the second: no it isn’t. After the third: no it wasn’t. But that would be much too literal. What those three paragraphs have in common are the three things that go to make up the Tom Wolfe effect. One, a glibness that is designed for speed-reading. Two, a facility with rapidly cross-cut images and references: a show of learning. Three, a strongly marked conservatism. It is the third of these features, Wolfe’s subliminal advertising for the New Right, that has had the least attention. But in this collection of his favourite journalism the artifice and the foppery are not sufficient to conceal it.*

Wolfe had the excellent idea, way back when, of being in the 1960s but not quite of them. His idea of participation was to appear, but to appear detached. The formula caught and held a whole imitative school of lycanthropic scribblers, who could mock and jeer at the antics of the period without being so square as to be left out of the party altogether. The summit of this style – its glass of fashion and its mould of form – was attained by Wolfe himself when he attended Leonard Bernstein’s never-to-be-forgotten cocktail party for the Black Panthers. ‘Radical chic’ has passed so far into the Anglo-American argot that it may be futile, thirteen years later, to attempt to expose it. For one thing, it was so nearly right. Everybody knew somebody who answered or fitted the description. For another, the older and cleverer phrase – limousine liberal – had gone out with Adlai Stevenson and needed a retread. To take up Radical Chic now (excerpted in this volume) and to turn its pages is to undergo a disturbing experience compounded of déjà vu and disappointment. Was there really a time when Park Avenue bled for the American black – even for his most egregious and posturing spokesmen? And did Wolfe really finish off the 1960s by holding up the Bernsteins to ridicule and contempt? Finally, was he just having fun? The answers to these questions supply the key to the Wolfe code.

Yes, there was a time when Park Avenue bled for blacks, for Vietnamese, for grape-pickers and draft-evaders and the rest of it. That time is long past. Today, the ruling style is overwhelmingly narcissistic or outright conservative or both. The national tone is set more by Nancy Reagan’s lavish White House, and by the ‘new opulence’ of the private jets massed at Washington National Airport. It is also set, some might argue, by the distribution of surplus cheese to lines of unemployed people of all colours. These days, Tom Wolfe is a guest at the White House, sometimes making up a table with the William F. Buckleys. Any magazine editor in America would pay any sum for an article by him on the absurdities of such evenings. But he seems oddly reluctant to abuse hospitality from that quarter. Yes, Wolfe changed the way people thought about the 1960s. He made people feel embarrassed about their ‘emotional’ and spasmodic reactions to war and revolution. It might be clearer to say that he made them feel self-conscious about their lapses into commitment. And self-consciousness, often of the most exorbitant kind, has been the thing ever since.

Was Wolfe just having fun at the expense of the smart set? He certainly worked hard at coining his phrase. The words ‘Radical Chic’ appear eight times, capitalised, in the first nine pages. The effect-producing stuff about Manhattan celebrities works only if you know them. What Wolfe did, really, was not so much a social or stylistic satire as a political hatchet-job. Take, for example, his long and incongruous exegesis of Seymour Martin Lipset, who was then attempting to open a fissure between American blacks and American Jews. The uneasy context of Black Panthers at the Bernsteins made this general theory, for Wolfe, easy of illustration. So when Otto Preminger raised some awkward Middle Eastern question with the Panther leader Don Cox, Wolfe was onto it like a lynx:

Most people in the room don’t know what the hell Preminger is driving at, but Leon Quat and the little grey man know right away. They’re trying to wedge into the argument. The hell with that little number, that Israel and Al Fatah and UAR and MiGs and USSR and Zionist imperialist number – not in this room you don’t.

That was very perceptive: the ideological equivalent of what Wolfe elsewhere terms ‘status radar’. But, to most of his readers, his political shrewdness was irrelevant or went unnoticed. Radical Chic seemed like a good laugh at the expense of a traditional target: the well-heeled reformer otherwise known as the salon socialist, parlour pink, Bollinger Bolshevik, or more candidly and less attractively, as the do-gooder.

In a thoughtful and spirited article, Garry Wills once analysed the selfish commonplaces which underlie the anti-do-gooder school. He was in a strong position to do so, having been a star at William F. Buckley’s National Review even while it was heaping praise on Tom Wolfe (as it still does). Wrote Wills:

It takes a very dull or skewed acquaintance with our history to think that elite interest in reform arose at last (and only then as an aberration) when a composer-conductor got interested in restive blacks awash in the streets of his own town. He did, after all, compose the song ‘New York, New York’ – why should interest in the ‘coloured’ part of the city’s population arise from nothing but nostalgie de la boue. Is Mr Wolfe saying that blacks and Puerto Ricans and Chicanos are boue?

He added: ‘Capitalists revolutionised our society. Having started that process, the sorcerer’s apprentices cannot call it off overnight or blame the whole thing on cocktail parties for Cesar Chavez.’ That suggestive judgment would come as more of a surprise to his lazy fans than it would to Wolfe. He, at least, knows what he’s on about. As the 1980s advance, he is more and more frank about his convictions. These are: that the United States was stabbed in the back over Vietnam (‘The Truest Sport’); that welfare deliberately encouraged ghetto insurrection (‘Mau-Mauing the Flak-Catchers’); that elitist designers are responsible for the failings of modern architecture (From Bauhaus to Our House); that men of action have been fettered too long by wet liberals (The Right Stuff, ‘The Truest Sport’, passim). He once told me that his favourite journalist was Taki Theodoracopulos, best-known in America for his essay ‘Ugly Women’, which argues (surprise) that feminism is a neurotic disorder of the ill-favoured.

Ah, but does Wolfe write like a dream? Depends. He certainly has a gifted ear for American speech. He can even catch it without directly quoting it, as in this piece from The Pump House Gang:

The Mac Meda Destruction Company is . . . an underground society that started in La Jolla about three years ago. Nobody can remember exactly how; they have arguments about it. Anyhow, it is mainly something to bug people with and organise huge beer orgies with . . . They have Mac Meda Destruction Company decals. They stick them on phone booths, on cars, any place. Some mommy-hubby will come out of the shopping plaza and walk up to his Mustang, which is supposed to make him a hell of a tiger now, and he’ll see a sticker on the side of it saying, ‘Mac Meda Destruction Company’, and for about two days or something he’ll think the sky is going to fall in.

Others have their own preferred pieces. But there are two objections to the view of Wolfe as merely an elegant and sardonic chronicler of manners. The first arises simply from reading him for several chapters at a stretch. After a cloying interlude, his use of affectation becomes tiresome. The italics, the exclamation marks, the arch Capital Letters, the repetition of anecdotes and of keywords (‘lollygagging’ must appear dozens of times): all these begin to pall. Second, we have the testimony of somebody called Joe David Bellamy. Mr Bellamy appears, presumably with Wolfe’s warm approval, as the writer of an introduction to this anthology. Here he is in full spate:

Temperamentally, Tom Wolfe is, from first to last, with every word and deed, a comic writer with an exuberant sense of humour, a baroque sensibility, and an irresistible inclination towards hyperbole. His antecedents are primarily literary – not journalistic, and not political, except in the largest sense. All these years, Tom Wolfe has been writing Comedy with a capital C, Comedy like that of Henry Fielding and Jane Austen and Joseph Addison, like that of Thackeray and Shaw and Mark Twain. Like these writers, Tom Wolfe might be described as a brooding humanistic presence. There is a decided moral edge to his humour. Wolfe never tells us what to believe exactly; rather, he shows us examples of good and (most often) bad form. He has always proffered these humanistic and moral perspectives on his subjects.

Well! One wonders briefly what Wolfe would say if anyone else got himself promoted in this fashion. ‘Not political, except in the largest sense.’ Hah! Oh yeah? And as for the Comedy with a capital C . . .

It’s not that Wolfe cannot write really memorably. This passage, for example, has stuck in my mind ever since I first read it:

The traffic jam at the Phun Cat ferry, going south to the Ho Chi Minh trail, was so enormous that they couldn’t have budged even if they thought Dowd was going to open up on them. They craned their heads back and stared up at him. He was down so low, it was as if he could have chucked them under their chins. Several old geezers, in the inevitable pantaloons, looked up without even taking their hands off the drafts of the wagons they were pulling. It was as if they were harnessed to them.

And then:

For two days they softened the place up, working on the flak sites and SAM sites in the most methodical way. On the third day they massed the bomb strike itself. They tore the place apart. They ripped open its gullet. They put it out of the transport business.

Now it’s not as if, in ‘the largest sense’, Wolfe knows anything about Vietnam (he says of the year 1963 that it was a year ‘when the possibility of an American war in Vietnam was not even talked about’). But he followed the lurid, almost pornographic passage above with a bitter attack on the New York Times for eroding domestic morale in the face of the foe. It seems to me, therefore, that he is at best inconsistent in his attack on the politicisation of writing that occurred (according to him and others) in the 1960s. He is simply, as was once said of the old German ruling establishment, blind in the right eye. He devotes a whole section of ‘The “Me” Decade’ to a critique of pseudo-religious cults, blaming them all on the mushy permissiveness of the hippies and the Guevara left. You would never suppose that two of the most virulent sects, the Mormons and the Moonies, still provide muscle and money to the New Right of which Wolfe recently announced himself a charter member.

Peel away the hidden agenda of his prejudices, and the residue is precariously thin. A freakish trip with Ken Kesey, an idolatrous profile of the bootlegger and stock-car racer Junior Johnson, and various other bits of slumming. These are American ephemera, and good American ephemera, but it’s clear from the packaging and introduction of this collection that Wolfe wants to be taken more seriously than that. He wants to be thought of as an anthropologist, almost as an authority – which is why I have concentrated so much on his social and political hard core.

In Radical Chic Wolfe remarked that ‘moderate’ black politicians could be detected by their habit of wearing suits three times too large for them. He must have thought this to be clever (like the old Vietnamese ‘geezers’ in their ‘inevitable pantaloons’) because he made the observation several times. The other day, there took place in Washington (where I live) a meeting of moderate black politicians. I didn’t especially notice their dress, but I did notice that when one of their leaders made a speech about the hopes of the vanished 1960s, they wept. They were crying. Crying for the 1960s! For the resources that were meant for them, and which went on Vietnam. For the moral energy that has become so dissipated and introverted. Perhaps this is why Wolfe has started to lose his cutting edge. I suspect that he is running short of targets. His latest book, From Bauhaus to Our House, was a flop by his standards: people are not ready to believe that modern building and its disgraces are to be blamed on an imported conspiracy of pointy-heads. Indeed, the pointy-heads are out these days. Blacks and the poor are scarcely fashionable. Progressive talk is at a discount. The official line is that Vietnam was a war well worth fighting. In the crass, natural wealth of Reaganite Republicanism, Wolfe cannot find the snigger potential he found in Leonard Bernstein’s naive philanthropy. He now has the America he always wanted, and I hope it stays fine for him.

*The Purple Decades: A Reader by Tom Wolfe (Cape, 1983).

Diary

Operation Desert Storm

1991

THE GREEKS had a saying that ‘the iron draws the hand towards it,’ which encapsulates, as well as anything can, the idea that weapons and armies are made to be used. And the Romans had a maxim that if you wish peace you must prepare for war. Oddly enough, even strict observance of this rule is not always enough to guarantee peace. But if you happen to want a war, preparing for it is a very good way to get it. And, among the privileges of being a superpower, the right and the ability to make a local quarrel into a global one ranks very high. Local quarrel? Here is what the United States ambassador to Iraq, Ms April Glaspie, told Saddam Hussein on 25 July last:

We have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait. I was in the American Embassy in Kuwait during the late 1960s. The instruction we had during this period was that we should express no opinion on this issue, and that the issue is not associated with America. James Baker has directed our official spokesmen to emphasise this instruction.

Even as the latest in ‘smart’ technology grinds and punctures the Iraqi military, this amazingly explicit enticement to Saddam is still being debated. Did the United States intend to keep Iraq sweet by giving it a strategic morsel of Kuwait and access to the sea? Or did it intend to remind its Gulf clients that only American umbrellas could protect them from Iraqi rain? Or did it perhaps intend both? Those who think this too cynical might care to remember that Washington incited Iran to destabilise Iraq in 1973, and Iraq to invade Iran in 1980, and sold arms on the quiet to both sides throughout. As Lord Copper once put it, ‘the Beast stands for strong mutually antagonistic governments everywhere. Self-sufficiency at home, self-assertion abroad.’

Considerations of this kind tend to be forgotten once war begins, but one day the swift evolution from Desert Shield through Imminent Thunder to Desert Storm will make a great feast for an analytical historian. For now, everything in Washington has narrowed to a saying of John Kennedy’s, uttered after the Bay of Pigs, to the effect that ‘success has many fathers – failure is an orphan.’

The debate in Congress, which was very protracted and in some ways very intense, was in reality extremely limited. The partisans of the administration said, ‘If not now, when?’ and their opponents replied: ‘Why not later?’ The partisans of the administration said there would be fewer body bags if Saddam was hit at once, and their opponents replied feebly that all body bags were bad news. Only Senator Mark Hatfield, the Republican from Oregon, refused either choice and voted against both resolutions. In his speech announcing the immediate exercise of the powers Congress had conferred on him, Bush oddly borrowed a phrase from Tom Paine and said: ‘These are the times that try men’s souls.’ This line actually introduces Paine’s masterly pamphlet ‘The Crisis’, and goes on to talk scornfully of ‘summer soldiers and sunshine patriots’. In the present crisis, with the hawks talking of war only on terms of massive and overwhelming superiority, and the doves nervously assenting on condition that not too many Americans are hurt, almost everyone either is a summer soldier or a sunshine patriot.

This is true even of the surprisingly large peace movement, which has spoken throughout in strictly isolationist terms. True, there was some revulsion at the choice of 15 January for the deadline, because it is the officially celebrated birthday of Martin Luther King and many felt that Bush either knew this and did not care or, worse still, had not noticed. But, except for a fistful of Trotskyists, all those attending the rally in Lafayette Park last weekend were complaining of the financial cost of the war and implying that the problems of the Middle East were none of their concern. I found myself reacting badly to the moral complacency of this. Given the history and extent of US engagement with the region, some regard for it seems obligatory for American citizens. However ill it may sound when proceeding from the lips of George Bush, internationalism has a clear advantage in rhetoric and principle over the language of America First. The irony has been that, in order to make their respective cases, both factions have had to exaggerate the military strength and capacity of Iraq: Bush in order to scare people with his fatuous Hitler analogy, and the peace camp in order to scare people with the prospect of heavy losses. Therefore, as I write, American liberals are coming to the guilty realisation that unless Saddam Hussein shows some corking battlefield form pretty soon, they are going to look both silly and alarmist. Surely this cannot have been what they intended?