Under Swiss Protection E-Book

15,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ibidem

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

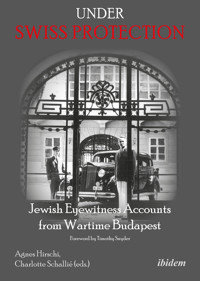

This volume retraces Carl Lutz’s diplomatic wartime rescue efforts in Budapest, Hungary, through the lens of Jewish eyewitness testimonies. Together with his wife, Gertrud Lutz-Fankhauser, the director of the Palestine Office in Budapest, Moshe Krausz, fellow Swiss citizens Harald Feller, Ernst Vonrufs, Peter Zürcher, and the underground Zionist Youth Movement, Carl Lutz led an extensive rescue operation between March 1944 and February 1945. It is estimated that Lutz and his team of rescuers issued more than 50,000 lifesaving letters of protection (Schutzbriefe) and placed persecuted Jews in 76 safe houses—annexes of the Swiss Legation. Based on interviews with Holocaust survivors in Canada, Hungary, Israel, Switzerland, the UK, and the United States, this volume shines a light on the extraordinary scope and scale of Carl Lutz’s humanitarian response.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 485

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

Timothy Snyder

Foreword here

Agnes Hirschi and Charlotte Schallié

1. INTRODUCTION here

Translators’ Notes here

Editors’ Notes here

Timeline here

François Wisard

2. CARL LUTZ IN BUDAPEST here

Context and Milestones of the Rescue Activities of Carl Lutz and His Team

3. THE RESISTANCE MOVEMENT here

Paul Fabry

“Carl Lutz stood out like a monument—He was an example of what can be done” here

Mordechai Fleischer

“On the nineteenth of March 1944, all of us went underground” here

Jean Greenstein

“We tried to save whoever we could, however wecould” here

David Gur

“Every moment, every slip of paper meant human life” here

4. PROFILES OF SURVIVORS: INTERVIEWS BY AGNES HIRSCHI (2000–2017) here

Klári Barna

“Klári, an Arrow Cross man is looking for you” here

Vera Bellák (as told by Támas Bellák)

“During the bombardments, we hid ourselves in the pantry” here

Eva Bino (as told by Peter Bino)

“Eva never spoke about her childhood” here

Agnes Heffner

“She refused to let the star be sewn onto her clothing” here

Iván Sándor

“The Red Cross and the Swiss legation had retrieved us from a death march” here

Rabbi József Schweitzer

“I will never forget the horrors of the war years” here

André Sirtes

“The American air raid saved our lives” here

Eva Szirmai

“I was too young to understand the situation” here

Agnes Teichman

“In my breadbasket, I would smuggle letters for the prisoners” here

5. TESTIMONIES here

Irena Braun Lefkovic

“I did not give up trying to get to no. 29 Vadász utca” here

Tzipporah Cohen

“I took the doll, [{MISSING SYMBOL}], and we started making our way home” here

Agnes Heller

“I was proud of the small yellow star” here

Idit Hirschfeld

“Our skirts were filled with the money our wise grandmother had sewn into our hems” here

Agnes Hirschi

“The man who changed my life” here

Hedva Katz

“I remember it was a house built of glass” here

Naomi Katz

“Shmulik played the accordion and we all sang Hatikvah on the ship’s deck” here

Shmuel Katz

“My fate was the exception” here

Ester Kaufman

“Unlike adults, I don’t think we, the children, realized the situation was that of life and death” here

Mordechai László Kremer

“The movement began to provide us with false documents” here

Judith Miriam Maté (as told by Janos Maté)

“I didn’t know for what I was liberated. The only reason was my son” here

Agnes Misan

“We were the last ones to get inside the Glass House” here

Mordechai Neumann

“Arthur Weisz paid with his life for having saved us”here

Miryam Palgi

“And suddenly they called me saying that my father came back”here

Peter Pollak

“To this day, I have not been able to understand how she managed to find my father’s Kiddush cup” here

Alexander Schlesinger

“On October 20, at five o’clock in the morning, my Holocaust began” here

Rabbi Arthur Schneier

“I had many Christian friends who came to our home; all that changed on March 12, 1938, when the Nazis took over” here

Moshe Shavit

“Our mother convinced us to stay with Aunt Hannah under Swiss protection” here

Shulamit Shtauber

“We were forced out of the bunker with tear gas and shoved naked in the snow” here

Peter Tarjan

“The last time I saw my mother” here

6. TRIBUTES AND LETTERS here

Charles Gati

“Remembering 1944 and Carl Lutz” here

Steven Thomas Geiger

“We were left with what is the most precious: our lives” here

George Somogyi

“Tribute to Carl Lutz” here

Geoffrey Leonard Tier

Letter to Carl Lutz (1945) here

Michael Vertes

“Diplomats are not expected to be heroes taking risks” here

7. APPENDIX: EXCERPTS FROM SWISS COLLECTIVE PASSPORTS NO. 1 & NO. 2here

GLOSSARY here

Foreword

To return to Holocaust is to pass through the recollections of an individual human being, a survivor whose memories lead us to the question of survival but only begin to suggest the answers. We speak now, perhaps too easily, of “human rights,” but the individual Jews threatened by Germans (and by their neighbors) had no such rights. They survived when someone attached them to a political community. To be reduced to the bare human condition, as Hannah Arendt understood, was to die. Germany killed Jews by separating them from states, sometimes gradually as with its own Jewish citizens, sometimes rapidly by invasions intended to destroy statehood as such. To survive, a Jews had to escape this process.

Carl Lutz was a Swiss diplomat in Hungary, and an account of his actions is the history of human and diplomatic recognition in a time and place where sovereignty was uncertain and Jews were being murdered by the tens of thousands. After the Soviet Union and Poland, countries invaded by Germany whose Jews lost citizenship, Hungary was the home to the largest Jewish community in Eastern Europe. Before March 1944 Hungary was a Germany ally that had passed anti-Jewish legislation, directly killed Jews beyond its borders in certain cases, and exploited Jews in labor battalions in ways that often led to their death in large numbers.

Until Germany occupied Hungary in March 1944, it had not implemented a policy designed to kill its Jewish citizens as such. When Germany sent its armed forces into Hungary, it dispatched its own experienced deportation authorities. It also changed the nature of domestic politics, receiving cooperation from Hungarian police and other institutions that led to the deportation and murder of most of the Jews of the Hungarian provinces. Under Western pressure and aware that Germany would lose the war, the Hungarian head of state, Miklos Horthy, ordered an end to the deportations on July 6. This left the Jews of Budapest, the Hungarian capital, as the largest group of Jews still alive whom it was still the German aim to kill. Most but not all of these Jews were citizens of Hungary.

Throughout Europe and throughout the war, it was the diplomats who were capable of providing critical assistance to the largest numbers of Jews. If a Jew was a citizen of a state which Germany had not claimed to have destroyed, and which still recognized its Jews as citizens subject to its protections, that Jew would almost certainly survive. Such actions were routine and required no initiative or courage on the part of diplomats or authorization from their superiors. We would not say that a Swiss diplomat who assisted a Swiss national who was Jewish took part in a rescue, since neither person faced any great risk.

In a time and place such as Hungary in 1944, where everything essential about the Holocaust was known and local sovereignty was in confusion, diplomats could play a more unusual role, providing forms of recognition and documentation to Jews who were not citizens of the countries they represented. This book brings together the recollections of the Jews who sought such help from Swiss diplomats, and the motivations and possibilities of those Swiss diplomats, above all Carl Lutz, who sought to help and did help. In other words, it brings together the Holocaust as experienced by its victims and the Holocaust as countered by representatives of institutions, those who used their authority in special, and sometimes quite ingenious, ways. They offered various forms of diplomatic protection to very large numbers of Jews who would otherwise have been killed, and did so at growing risk to themselves.

The diplomat is not the image of the rescuer that leaps to our imagination, perhaps because we associate rescue with the irrational human gesture of solidarity (which is true enough in many cases), perhaps because we associate bureaucrats in these settings rather with death than with life. To be sure, the daily work of any diplomat is beset by complications and ambiguities. Diplomats of countries that remain neutral can find themselves in particularly trying and complicated situations. Carl Lutz, for example, represented the interests of Nazi Germany in Palestine in September 1939, as Germany invaded Poland and began the Second World War in Europe, and was responsible for the evacuation of German diplomats.

Lutz and his colleagues in Switzerland were effective precisely because they understood the situation in which they were operating, and made effective and creative use of the available tools. At first, they were not taking risks themselves, but by the end they certainly were. After Germany installed a government of the Hungarian fascist movement (the Arrow Cross) in October 1944, tens of thousands of Jews were murdered in Budapest, and some of their protectors were also attacked. After the Red Army took Budapest in January 1945, diplomats who had assisted Jews were deported to the Soviet Union.

Lutz's capacities were greater than those of other diplomats because of his special institutional position. As the representative of British interests in Hungary, he could contemplate sending Jews to Palestine, which at that time was still a territory of the British Empire. By bringing local representatives of the Jewish Agency under the protection of the Swiss government, Lutz vastly multiplied the institutional capacity available to assist Jews. In this special configuration, Lutz in his official capacities linked the rulers of the lands that would soon become Israel with the Jews who hoped to organize emigration to those lands and to found such a state. It is to Lutz's great credit that he understood so well the needs of individuals and the possibilities of institutions.

This will be, perhaps, the great theme of the still-unwritten history of diplomatic rescue during the Holocaust: the indispensability of both institutions and humanity. The work collected here, in its sensitivity as well as in its synthetic judgments, is a first step towards such a history. It provides a portrait of perhaps the most significant of the diplomatic rescuers, and so insight into how states and people save lives, states if they are guided by principles, people if they are principled.

Prof. Dr. Timothy Snyder

Yale University

October 2017

1.INTRODUCTION

Agnes Hirschi and Charlotte Schallié

There are many individuals, unsung heroes, who are trying to make this a better world by selflessly doing the “right thing.” Carl Lutz did just that on a profound scale.

Janos Maté

In this book, we retrace Carl Lutz’s wartime diplomatic rescue efforts in Budapest, Hungary, through the lens of Jewish eyewitness accounts and survivor testimonies.

Carl Robert Lutz (1895–1975) was the Swiss vice-consul and the head of the foreign interests division of the Swiss legation in Budapest during the last three years of the Second World War. Lutz also represented British interests in Hungary. Initially, he was involved in negotiations to transfer over 10,000 Jewish children and young adults to Palestine. Together with his wife, Gertrud Lutz-Fankhauser, the director of the Palestine Office in Budapest, Moshe Krausz, fellow Swiss citizens Harald Feller (1913–2003), Ernst Vonrufs (1906–1972), Peter Zürcher (1914–1975), and underground Zionist youth movements, Carl Lutz led an extensive rescue operation between March 1944 and February 1945. It is estimated that Lutz and his team of rescuers issued more than 50,000 lifesaving letters of protection and safe conduct passes (Schutzbriefe; Schutzpässe) and placed persecuted Jews in seventy-six safe houses—annexes of the Swiss legation in Budapest. Under Swiss protection was also the Glass House on 29 Vadász utca. The foreign interests division of the Swiss legation opened its emigration office in the building on July 24, 1944. After the Nyilas (Arrow Cross) coup on October 15, 1944, the Glass House became the largest Swiss-protected safe house in Budapest sheltering up to 3,000 Jews.

Other diplomats such as Raoul Wallenberg and Papal Nuncio Angelo Rotta adopted Lutz’s rescue strategy and also issued many letters of protection, passports, and certificates for those in need. Yet, due to its scope and meticulous execution, Lutz’s high-risk operation is considered the largest and most successful civilian rescue mission during the Second World War (Tschuy 1995). Over seventy years later, it continues to serve as a blueprint for humanitarian diplomacy work in a conflict-ridden world.

The thirty-six testimonies of Holocaust survivors and eyewitness accounts compiled in this edited book were conducted within a seventeen-year time span (2000–2017) in Canada, Hungary, Israel, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. When we conceived this joint project in 2015, we were mindful not to privilege certain subgenres of testimonies and survivor accounts over others. Instead, we decided to organize the individual chapters according to different forms of testimony, including a diverse range of genres, formats, and modes of reflection. To accommodate multiple methodological approaches, we use the term testimony not in a juridical sense but define it broadly as “a transmission of information, for which there is an internal, unrelenting pressure to convey as well as an external readiness and eagerness to receive it” (Dori Laub 2014).1

In Chapter 2, François Wisard provides a historical timeline which situates Carl Lutz’s lifesaving activities—his pre-1944 efforts to facilitate the emigration process for Jewish child refugees to Palestine—within the framework of other diplomatic and International Red Cross rescue missions in wartime Budapest. Wisard’s reflections on the intricate nature of the Swiss-led rescue mission lead to Chapter 3, which features four testimonies from former members of four Zionist youth movements: Bnei Akiva, HaNoar HaTzioni, Hashomer Hatzair, and He-Halutz. In this chapter, we also include a non-Jewish eyewitness account from Paul Fabry. Fabry, who was part of the military resistance in Hungary, assembled a group that was allegedly tasked with guarding the Glass House. While his fake military unit pretended to hold the Glass House residents their prisoners, he and his soldiers actually protected the Jewish residents from Arrow Cross raids and arrests. His recollections remind us of how many individual acts of resistance contributed to the Swiss-led rescue mission:

There was no such thing as a safe Jew without dozens involved. The one who let him into the house; the one who took him to the taxi; the one who gave him a few pennies; the other who fed him; the one who ran from one place to another with a false certificate; the one who made the telephone call to tell him to run. It was a chain of events, and a single second mattered. Where in that second could somebody help? Was someone there to come to your rescue? Was somebody there to give you that paper? No one alone could save the thousands persecuted. And this also goes for Lutz. Lutz was a hero but he needed hundreds to help.

Agnes Hirschi, a former journalist and Holocaust survivor herself, engaged with her interview participants in a dialogical and co-creative process. Her profiles of survivors (Chapter 4) are largely recounted in third-person narratives which refract the witnesses’ life histories through the eyes of the interlocutor. This collaborative approach between the interviewer and the interviewee is informed by an understanding that witnesses’ memories do not exist in an abstract vacuum but are mutually constituted and mediated in a dialogical setting (Greenspan and Bolkosky 2006).2

Chapter 5 includes written testimonies provided by survivors, transcripts from Daniel von Aarburg’s documentary film (Carl Lutz—The Forgotten Hero, 2014), and singletestimony interviews that we conducted with the intent of archival preservation. Some survivors recollect the events of 1944 in vivid detail, while others interweave memory with philosophical and historical reflection borne of years of learning and investigation into their pasts. Some survivors have been reluctant to share their memories with family members until recently, others drew on unpublished memoirs. With one exception, all testimonies were recorded at home with spouses, children, and caretakers in attendance. Our interviews encompass survivors who were four years old in 1944, others who were in their mid-twenties and involved in the rescue mission themselves. Given the wide age range among our interviewees, recollections vary greatly: some reflect a child’s perception, while others reflect an adult’s perspective.

Our (video)testimony format is based on the interview protocols developed by the USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education and the interview guidelines suggested by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. During the testimony interviews, we were mindful to remain engaged listeners, to interject ourselves as little as possible so as to respect a process of recollection that often unfolded in “streams of consciousness.” All the survivors who were interviewed in person showed an urgent need to bear witness—this was often clearly expressed at the moment of first contact on the phone. When memory recollection was more challenging due to survivors’ advanced age, we asked their children to mediate the testimony-giving. In such situations, the format was adapted to fit individual needs and circumstances becoming a collaborative remembrance with survivors and their children.3

Given the specific format requirements in this book, all transcripts have been translated from German and Hebrew, and are edited and condensed. The difficult task of rendering an oral testimony into a written document necessitated further collaborative efforts among survivors, interviewers, translators, editors, and copy editors. Although the processes of remembrance follow cyclical and repetitive patterns, we chose to adopt a linear narrative for all accounts and testimonies. In order to facilitate our team-centered collaborative model, all of us employed a kaleidoscopic approach (we borrow the term from Mark Roseman4) while paying close attention to the interplay between content, process, and form. The contributions of our excellent translators and copy editors—Dahlia Beck, Noga Yarmar, Lauren Thompson, Karine Hack, and Emma Woodhouse—have been integral to this project, so we have included a section with translators’ notes and editors’ notes to ensure that the nature of our shared inquiry is as transparent as possible.

In our final chapter, we feature tributes and letters to Carl Lutz. We are deeply grateful to all the survivors who entrusted us with their life stories in both personal conversations, interviews, and written testimonies. This book is dedicated to them.

References

“Collecting Testimonies.” USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education, n.d. Web. February 15, 2015.

Greenspan, Henry. “Collaborative Interpretation of Survivors’ Accounts: A Radical Challenge to Conventional Practice.” Holocaust Studies (2011) 17.1: 85–100.

Greenspan, Henry. On Listening to Holocaust Survivors: Beyond Testimony. St. Paul, MN : Paragon House, 2010.

Greenspan, Henry and Sidney Bolkosky, “When is an interview an interview? Notes from listening to Holocaust survivors.” Poetics Today (2006) 27.2: 431–449.

Greenspan, Henry, Sara R. Horowitz, Éva Kovács, Berel Lang, Dori Laub, Kenneth Waltzer and Annette Wieviorka. “Engaging Survivors: Assessing ‘Testimony’ and ‘Trauma’ as Foundational Concepts,” Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust (2014) 28.3: 190–226, DOI: 10.1080/23256249.2014.951909

“Oral History Interview Guidelines.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2007. Web. February 22, 2015.

Tschuy, Theo. Carl Lutz und die Juden von Budapest. Zurich: Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 1995.

Tschuy, Theo. Dangerous Diplomacy: the Story of Carl Lutz, Rescuer of 62'000 Hungarian Jews. Grand Rapids, Michigan: W.B. Eerdmans, 2000.

Vámos, György. Carl Lutz (1895–1975). Schweizer Diplomat in Budapest 1944. Ein Gerechter unter den Völkern. Geneva: Editions de Penthes, 2013.

von Aarburg, Daniel. Carl Lutz—Der vergessene Held (Carl Lutz—The Forgotten Hero). Documentary Film. Docmine Productions, 2014.

1 Henry Greenspan, Sara R. Horowitz, Éva Kovács, Berel Lang, Dori Laub, Kenneth Waltzer and Annette Wieviorka. Engaging Survivors: Assessing ‘Testimony’ and ‘Trauma’ as Foundational Concepts, Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust (2014) 28.3: 199.

2 Henry Greenspan and Sidney Bolkosky, “When is an interview an interview? Notes from listening to Holocaust survivors.” Poetics Today (2006) 27.2, 432–433.

3 Thus, when multiple interviewees were co-interpreting survivor testimonies, the communal act of retelling closely resembled the “knowing with” process described in Henry Greenspan’s work with Holocaust survivors.

4 Mark Roseman, “Foreword,” Approaching an Auschwitz Survivor. Holocaust Testimony and Its Transformations, ed. by Jürgen Matthäus. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010: vi.

Translators’ Notes

Dahlia Beck

The precepts that guided me as I was translating Hungarian–Israeli Holocaust survivors’ testimonies, from Hebrew to English, emerged and interwove during the course of decoding and constructing the texts. As the translation project progressed, the testimonies transposed later modified those I interpreted earlier, thus subtly reshaping the translation tenets that informed me.

Oral vs. written: I was mindful of the written testimonies requiring translation being transcriptions of oral interviews. As such, they consist of accents, body language, facial expressions, gestures, tone of voice, and so on, all of which help the listeners follow and make sense of the interviewees’ discourse. As a translator, I had to take a decoding stand based on words on a screen/page and their copious translation possibilities.

Hungarian–Hebrew–English: The Hungarian survivors’ Hebrew ranges from awkward to incorrect; this is not surprising, given that Hebrew is their second language, and that most of the interviewees had to function in Hebrew immediately upon arrival in their new homeland, without any formal instruction. The third language, English, introduced its own linguistic norms and patterns. As a translator, I took care of blatant mistakes (e.g., noun–verb agreement), and minimized multiple repetitions. However, I opted to leave certain idiosyncratic figures of speech as is—without compromising on clarity—since they were so evocative.

Moreover, these distinctive phrasings often channeled a particular “European flavor,” resonating with the aura of the stranger, the cosmopolitan, and the wanderer, the polyglot, the victim, the fighter, and the survivor, in ways that normative English could not.

An additional conviction that supported leaving quirky locutions word for word is that they act as a wake-up call. Reading accounts of the horrors the interviewees underwent can numb the reader. The occasional odd phrasing is a visible (or auditory) reminder of the testimony giver’s mother tongue and of their perfidious homeland—Hungary, requiring the reader’s heightened attention.

Finally, an awkward expression, as I have come to perceive it, humanizes the testimony giver, rendering each one unique and invoking their singular accent and voice.

Language mirroring content:The occasional repetition and non-sequitur, an incomplete sentence, a thought trailing off, the pervasive staccato style—I gradually came to view these as reflecting the content recounted by the survivors. Their world fell apart abruptly and brutally; likewise, the rhythm and style of the testimonies are often abrupt, brusque, cut to the bone and taut, echoing the inability of standardized language to give voice to the ghastly events it divulges. Thus, my translation respectfully accentuates the onomatopoeic atmosphere of the testimonies.

Lauren Thompson

Translating testimony, a medium that forms a central part of modern Holocaust studies, presents particular challenges because of individual voice and experience. In this case, as a translator it seems necessary to stay as true to the words used and attempt to maintain the voice of the survivor. In spite of this, every time a story is told and reinterpreted—even across the same language—it becomes a new story.

The sources for translation in Under Swiss Protection presented particular difficulties for translating because of the large variety of voices as well as the intermediaries that worked with the texts prior to and post initial translation. Many texts came pre-written as narratives with quotes from the survivor or their descendants, while others were transcribed from edited oral interviews. This variety meant that each text was a different task unto itself that had to be approached from a unique angle.

Fidelity, readability, and clarity are key to an understandable and considerate translation. I’ve chosen to translate the quotations of survivors and their descendants more directly and allowed for a bit more reworking of the narrative texts for clarity. I aimed to be as true to the original phrasing as possible without losing clarity in the target language (English).

Translating German to English always poses issues with sentence structure and sentence length. German allows for clauses that, when translated directly to English, appear cluttered or even incomprehensible. In my initial translations, I attempted to maintain similar sentence length, but with a structure that fits English norms. Sentences were only combined or cut shorter when it corrected grammar and the text came from an intermediary and not from the survivor themselves. In all the German texts, I chose to leave the order of information and paragraphs as they were given to me, intending to maintain the narrative as it was laid out by the survivor or in Agnes’ interview.

For terms that were specific to the experience of the Holocaust in Hungary, I aimed to use the terms most commonly used in academic English-language Holocaust literature. German idioms were translated fully to comparable English idioms when they existed.

Noga Yarmar

My involvement with this project began in 2015 when I was asked by Charlotte Schallié to accompany her to Israel to conduct interviews with Hungarian Holocaust survivors. I was the planner, tour guide, the translator, and the “Israeli” who put people at ease. Our second trip followed in May 2017. For me it has been a challenging, meaningful, and above all, illuminating journey. From the first phone conversation, I was struck by how willingly and without hesitation the survivors entrusted me, a complete stranger, with their stories. They were eager to talk and share their experiences and I sensed an urgency and desire to share their recollections before it was too late.

My guiding principle during this multistage process has been to remain authentic to the voices and experiences of the survivors I met, to understand what was said beyond their spoken words: in the unfinished sentences, the broken voices, and the silences. Even though it was difficult emotionally and physically for many to talk, they were determined to share their lives with us. Moreover, they were most thankful for our interest in hearing what they had to say. It was my privilege and honor to be a witness and to document these events. I am amazed by the survivor’s courage and what they overcame, thankful for their trust, inspired by their unwavering optimism, and forever changed by their words and memories.

Editors’ Notes

Karine Hack and Emma Woodhouse

In editing these testimonies and interviews with Holocaust survivors, our goal has been to distill the voices of the survivors so that readers can connect, empathize, and understand their very personal and intimate stories amidst the overwhelming horror of the Holocaust. Editing has been a delicate process during which we have attempted to preserve these singular voices, while also giving them greater clarity. Many quirks of language have been left so as to respect the diversity of these speakers, and the myriad ways of telling a story.

It has been important to us to maintain the survivors’ phrasing, and we have made great efforts to be as transparent as possible. In some cases, verb tenses and prepositions have been silently changed to make translated testimony fit more smoothly into English-language conventions, always with the reader in mind. We have also provided notes and explanations on historical dates, events, and people to give the reader context and clarity. Editing has been a collaborative and expansive process, evolving and changing as we have progressed.

We are honored to have worked with these stories and these voices, and they will stay with us as we move throughout life. We hope that these testimonies will inform and broaden your understandings by bringing humanity and reality to this moment in history, just as they have affected ours.

Timeline

March 1, 1920Miklós Horty is elected regent by the parliament. The Horty era lasts until October 16, 1944.

June 4, 1920 Signing of Trianon Peace Treaty. Hungary’s territory is reduced by two-thirds; the post-Trianon Hungarian population decreases from 18.2 million to 7.9 million.

September 26, 1920 Implementation of the numerus clausus law (Act XXV of 1920) restricting the number of Jewish students to Hungarian universities. The act establishes a quota of 6% for Jews.

May 29, 1938 Under the first “Jewish Law” (Act XV of 1938), Jewish participation in certain professional fields is limited to 20%.

January 1939 Hungary joins the Anti-Comintern Pact.

May 4, 1939 Second “Jewish Law” (Act IV of 1939); the law is aimed at limiting the number of Jews in certain professions to 6%. Further measures restrict civil rights of Jews in Hungary.

November 20, 1940 Hungary joins Tripartite Pact between Germany, Italy, and Japan.

June 27, 1941 Hungary joins the German invasion of the Soviet Union.

August 8, 1941 The third “Jewish Law” (Act XV of 1941) is enacted banning marriages between Jews and Christians.

July/August 1941 The National Central Alien Control Office (KEOKH) enforces the roundup of stateless Jews and some Hungarian Jews (who cannot produce identification papers) to occupied Soviet territory.

August 27–30, 1941 Einsatzgruppe C and Ukrainian militia men kill approx. 23,000 Jews—including all deportees from Hungary—at Kamenets Podolski (now Ukraine).

July 1942 Act XIV of 1941 enforces the already existing practice that all Jewish men between the ages of twenty and forty-eight perform unarmed auxiliary labor service duties.

March 19, 1944 German Occupation of Hungary (Operation Margarethe); Adolf Eichmann arrives together with his Sondereinsatzkommando (Special Operations Unit) in Budapest.

April 5, 1944 Jews older than six years of age are ordered to wear a (10 × 10 cm) yellow star.

April 28, 1944 A government decree orders ghettoization of Jews.

May 15, 1944 Mass deportations to Auschwitz commence. During the next fifty-six days, over 437,000 Jews are being deported from the Hungarian countryside by gendarmes, under the guidance of German SS officials. Many thousand Jewish deportees are also sent to the Austrian border in order to dig fortification trenches.

June 14 & 24, 1944Budapest mayoral decrees enforce the relocation of Budapest Jews into 1,951 designated yellow-star houses.

July 1944 On July 6, Horty halts all deportations. By the end of the month, the only remaining Jewish community in Hungary is in Budapest.

August 24, 1944Miklós Horty refuses to hand over the Jews living in Budapest.

October 15 and 16, 1944 The Arrow Cross Party seizes power.

November 17, 1944 Ferenc Szálasi orders to set up two ghettos in Budapest.

November 21, 1944Szálasi halts all “death marches.”

December 24, 1944– The Red Army lays siege to Budapest. Arrow

February 13, 1945 Cross units commit anti-Jewish terror and massacres across the capital city.

January 16–18, 1945 The Budapest ghettos—both are located on the Pest side—are liberated.

February 13, 1945 The Red Army liberates the Jews on the Buda side of the city.

April 13, 1945 The Soviet occupation of Hungary is completed. Between 1941 and 1945, over half a million Jews have been killed in Hungary.

Consulted Source:

Zoltán Vagi, László Csősz, and Gábor Kádár. The Holocaust in Hungary: Evolution of a Genocide. Lanham, Maryland: AltaMira Press in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2013.

2. CARL LUTZ IN BUDAPEST

François Wisard

Context and Milestones of the Rescue Activities of Carl Lutz and His Team1

The rescue activities of Carl Lutz and his team can only be fully understood in the context of the political developments of Hungary in 1944–1945 and of the rescue activities undertaken simultaneously by representatives of other neutral countries (see 1 and 2).

Lutz’s activities can by no means be attributed to the heroism of a single person, but rather to a collective effort under his leadership (see 3 and 4). This collective rescue effort through Swiss diplomatic protection led the way both in terms of chronology and the number of people saved (see 2 and 4).

1. Hungary and the deportation of the Jews

Carl Lutz arrived in Budapest in January 1942 and returned to Bern in April 1945 with other members of the Swiss diplomatic representation—all except its head and a colleague who were captured by the Soviets and taken to Moscow. During this period, events in Hungary can be divided into three distinct phases.

The first phase covers the period leading up to the occupation of the country by German forces on 19 March 1944. After pledging allegiance to Nazi Germany by formally joining the Axis alliance in 1940, Hungary had been able to annex parts of Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia, thus regaining territories it had lost in the wake of the First World War. It adopted three pieces of anti-Jewish legislation between 1938 and 1941, which were largely modelled on the Nuremberg Laws and effectively excluded Jews from state and public office. Hungarian troops also took part in the mass murders of Jews. Nevertheless, in the spring of 1944, Hungary was the last area under Axis control or influence in which the “final solution” had not yet been carried out. Some 750,000 Jews lived within its borders, some of whom had fled from Poland and, above all, Slovakia.

The situation changed on 19 March 1944: with the Soviet forces advancing and the Hungarian government giving every indication of its intention to switch sides and join the Allied camp, German troops invaded the country. Nazi Germany no longer had the means to sustain a lengthy, full-scale occupation and withdrew most of its troops again almost immediately. Miklós Horthy, Regent of Hungary since 1920, was forced to acquiesce to two different sets of measures: appointing a government that would collaborate with the Nazis and submitting to an armada of supervisors and counsellors headed by Edmund Veesenmayer, a German functionary who represented both Himmler and Ribbentrop. Adolf Eichmann arrived with his commando squad to oversee deportations. But even though Germany was the puppet master pulling the strings, Horthy was kept in position as head of state in order to uphold the fiction that Hungary remained a sovereign nation.

Eichmann and his commando squad lost no time in getting down to work. A timetable for rounding up Jews living in Hungary was quickly established, followed swiftly by their deportation. The first to be affected were Jews from the eastern, south-eastern and northern provinces—the areas closest to the approaching Red Army, and those most recently acquired by Hungary. The operation was scheduled to last no more than three months, culminating with the Jewish population of the capital. The first train left for Auschwitz-Birkenau on 15 May 1944, with Hungarian officials accompanying it as far as the border with Slovakia. More than 430,000 Jews from the Hungarian provinces were deported in just a matter of weeks, sparking a wave of protest: Pope Pius XII, US President Roosevelt and the King of Sweden all sent messages to Horthy demanding that the deportations cease. The US air force bombed Budapest. Horthy called a halt to the deportations on 6 July. The Hungarian provinces had been emptied of their Jewish populations. Only the community in the capital, Budapest, remained.

Two contradictory developments emerged over the summer: on the one hand, the capital city’s Jewish citizens were forced to wear a yellow star and affix similar markings to the buildings in which they had to live. On the other, the most pro-German members of the government were removed.

The third phase began on 15 October 1944. Head of state Horthy, having just announced that Hungary would be ceasing all hostilities against the Allies, was forced to cede power to Ferenc Szálasi, the leader of the Arrow Cross Party (Nyilas), the Hungarian equivalent of the national socialists. The new minister of the interior promptly announced that the government would stop honouring the protective documents that were being issued—as we shall see—by the neutral states. However, in the hope of Hungary itself being recognised by the neutral countries, the new regime gave into pressure and this particular measure was never enforced.

This final phase can be characterised by three main features: Firstly, it was a period marked by chaos, uncertainty and—above all—violence. Nyilas gangs carried out incessant raids, attacking Jews and even executing them on the banks of the Danube before dumping their bodies in the river. Neutral diplomats were not spared in these attacks: the Swedish legation was attacked on 24 December and the head of the Swiss legation kidnapped and tortured on 29 December. More than 60,000 Jews are estimated to have fallen victim to Arrow Cross regime. In November, tens of thousands of Jews were forced to march towards the Austrian border. During these “death marches”, representatives of neutral countries and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) strove to deliver protective documents to the deportees.

Secondly, two large ghettos were established in November in the Pest district. The “international ghetto” consisted of 122 safe houses on the banks of the Danube around Pozsonyi út, which were placed under the protection of the neutral powers. These buildings—modern apartment blocks, four to six storeys high—were now expected to house more than 20,000 Jews in possession of a protective document issued by a neutral country, whether genuine or forged. The majority of the houses (76 in total) were placed under Swiss protection, the others were assigned to Sweden (33), Spain, Portugal, the ICRC and the Swedish Red Cross. The central ghetto—also known as the “Big Ghetto”—was set up near the main synagogue. More than 60,000 Jews were confined there, several thousand of whom had been forcibly relocated from the international ghetto by the Arrow Cross regime.

Last but not least, everyone was aware that the imminent approach of the Red Army made the liberation of Budapest inevitable. Having crossed into Hungarian territory at the end of October, General Malinovsky aimed to take the capital city by the beginning of November. However, dogged resistance from the German troops and their Hungarian allies meant that Budapest was not fully encircled until Christmas that year. Pest, on the Danube’s left bank, was liberated on 17 January 1945, with Buda on the right bank following one month later. The siege of Budapest claimed 160,000 lives in total.

2. The neutral powers in Budapest2

Alongside Jewish organisations, the diplomatic representatives of the neutral countries played a central role in efforts to save the Jews of Budapest. Some leaders of the Jewish community negotiated with the Nazis, ultimately enabling almost 1,700 Jews to escape to Switzerland in 19443. We are more interested in the five neutral states which had diplomatic representations in the Hungarian capital: the Holy See, Spain, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland4.

The neutral countries issued protective documents to a number of Jews, or arranged for such documents to be issued. While the Hungarian authorities permitted only a limited quota of “protective letters”, they are known to have been forged en masse and even to have exchanged hands for money. It is therefore impossible to put an exact figure on how many documents were issued by the neutral states, and numbers tend to vary depending on the source. We must content ourselves with orders of magnitude. While recognising that these documents afforded a certain degree of protection, it should be stressed that the latter was by no means absolute—especially following the seizure of power by the Arrow Cross Party on 15 October.

Apostolic Nuncio Angelo Rotta (1872–1965) was instrumental in coordinating the approach adopted by the neutral powers. A first united protest against plans to deport Jews was lodged on 21 August 1944. A second protest note, drafted during a meeting at the Nuncio’s quarters on 15 November, called for an immediate halt to the persecution of the Jewish population. While the neutrals generally stepped up their coordination from this point forward, in the latter stages of the war, efforts were spearheaded by the Swiss and the Swedes, sometimes accompanied by representatives of the Nunciature and the ICRC. The Nunciature also gave out protective documents. Granted permission to issue 2,500 passes, primarily to Jewish converts to Christianity, it was eventually able to distribute at least six times as many. Hungary was the only country in which Pope Pius XII publicly intervened to aid in the rescue of persecuted Jews and where his nuncio worked together with other diplomats. Rotta was elevated to the rank of Righteous Among the Nations posthumously in 1997.

The Spanish legation had been run by a chargé d’affaires, Angel Sanz Briz (1910–1980), since the summer of 1944. In July that year, he was authorised to allow 500 Jewish children to emigrate to Tangiers, which at that time was under Spanish occupation. He issued protective papers to the 200 children in Budapest included in this quota. After the war, he wrote that he was able to enlarge the number of permits granted him by treating each child as a family. At the beginning of December, Spain gave in to Nyilas demands and removed its chargé d’affaires from the Hungarian capital, ordering him to leave for Sopron on the Austrian border under the pretext of evading the approaching Red Army. Italy’s Giorgio Perlasca (1910–1992) stepped into the role vacated by San Briz and signed the protective passes issued by Spain. Like the Swede Raoul Wallenberg and the Swiss Peter Zürcher and Ernest Vonrufs, he continued to act in this manner until the liberation of the Pest ghettos, inside whose walls the Jews were confined. Sanz Briz was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations in 1966, Perlasca in 1988.

The Portuguese legation in Budapest was authorised to issue provisional passports to Jews with links to Portugal or Brazil—a country whose interests Lisbon represented in Germany. It handed out some 800 passes. There were many changes at the head of the legation: Minister Carlos Sampaio Garrido (1883–1960) was forced to leave Budapest after being arrested at his residence in the company of Jewish guests. He was replaced by chargé d’affaires Alberto Teixera Branquinho (1902–1973) until the end of October, then by a consul until early December. The title of Righteous Among the Nations was bestowed upon Sampaio Garrido in 2010.

Unlike Spain and Portugal, neither of which—strictly speaking—had a proper diplomatic representative in the Hungarian capital at the end of 1944, Sweden and Switzerland found themselves in a unique diplomatic situation when dealing with the Hungarian authorities. Sweden represented Hungary’s interests in Washington, London and Berlin as well as the interests of the Soviet Union in Hungary. Switzerland represented the interests of a dozen countries that had severed diplomatic relations with Hungary, including the United States and Great Britain. This situation not only required the two countries to maintain a minimum diplomatic presence, it also enabled them to restrict or enlarge their field of action as appropriate to come to the aid of the persecuted Jews.

There was remarkably little turnover in Sweden’s diplomatic personnel. The legation in the Buda district was run by Minister Carl Danielsson (1880–1963) until he sought refuge at the residence of the head of the Swiss legation on 25 December 1944. Danielsson was effectively aided first by Per Anger (1913–2002), then Lars Berg. In mid-June, he requested permission to issue emergency passports for Jews with connections to Sweden who found themselves under threat of deportation. One month later, he had issued around 450 such papers. The legation took steps to clear the emigration process with the Hungarian and German authorities, at the same time as Switzerland was involved in negotiations to obtain permission for some 7,000 Jews to leave for Palestine.

Reinforcement arrived on 9 July in the form of Raoul Wallenberg (1912–?), whose relatively vague mandate had been formulated in Stockholm by the ministry of foreign affairs in cooperation with the local representative of the War Refugee Board, the agency established by President Roosevelt in early 1944 to aid the Jews. Wallenberg was formally head of a new section of the legation (Section B), for which he rented private office space in Buda. Initially, he was only meant to stay for two months with the primary aim of gathering information and reporting back to Stockholm on how the situation of Hungary’s Jewish population was likely to unfold.

Wallenberg swiftly contacted Lutz to learn from the protective measures taken by the Swiss. He, too, began issuing protective documents—or, more specifically, protective passports. Around 5,000 had been printed by 10 September and some 2,000 distributed, amidst frequent complaints to Stockholm about the lack of financial resources. After 15 October, he redoubled his efforts, moving his offices to the Pest district. In addition to the section’s staff of several hundred, most of them Jews, the new premises also became home to 700 people. Wallenberg proved to be particularly active on the ground in Pest during the last few weeks that preceded his capture by the Soviets on 17 January. He cannot, however, be credited as the person who saved the 60,000 or 70,000 Jews walled up inside the Big Ghetto by thwarting the Arrow Cross Party’s intention to attack it in January 19455.

Another Swedish agent had appeared on the scene in July 1944. Valdemar Langlet, a former journalist living in Budapest, who had already begun issuing protective papers two months’ previously although not authorised to do so, insisted on being appointed the local representative of the Swedish Red Cross. Formally required to report to Danielsson, he nevertheless ran his own independent operation, during which the number of protective documents produced far exceeded the authorised quota of 400.

Carl Danielsson (1982), Per Anger (1980), Lars Berg (1982), Raoul Wallenberg (1963) and Valdemar and Nina Langlet (1965) were all recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

3. The Swiss and the International Committee of the Red Cross

Vice-Consul Carl Lutz (1895–1975) was stationed at the Swiss legation in Budapest from January 1942 as the head of the foreign interests division6. Born in eastern Switzerland in 1895, he emigrated to the United States in 1913, where he met his future wife, Swiss-born Gertrud Fankhauser (1911–1995). He also worked for several Swiss representations, including the legation in Washington. In 1935, he was transferred to the Swiss consulate in Jaffa and placed in charge of the chancellery under Consul Jonas Kübler. In September 1939, Lutz was entrusted with organising the representation by Switzerland of German interests in Palestine and Transjordan, and particularly with arranging the departure of German diplomatic and consular staff—a task that proved to be short-lived. On 22 October 1939, Lutz confirmed that Spain would henceforth be representing the interests of German nationals. He returned to Switzerland a year later.

In Budapest, Lutz was required to safeguard the interests of a dozen or so states, including the protection of diplomatic property. He set up office in the building that had previously housed the US legation on Pest’s Szabadság tér (Liberty Square), while taking up residence in the former British legation in Buda. From 1942 onwards, Lutz and his staff, about 20 strong, issued 300 to 400 protective passports (Schutzpässe) to US and British citizens, both Jews and non-Jews, and subsequently distributed 1,000 such papers to Yugoslav citizens. These documents inspired the Swedes to establish protective passports for Jews with connections to Sweden.

Lutz’s division, whose activities will be detailed in the next section, continued to grow. Its work was overseen by the Swiss diplomat until Christmas 1944 when Budapest was encircled by the Red Army and Lutz was no longer able to leave the safety of his residence. He appointed two deputies to carry on his work in the Pest district, where the Jews were under threat: Peter Zürcher (1914–1975) and Ernst Vonrufs (1906–1972), Swiss nationals who worked in the local textile industry. Both intervened in favour of the Jews until Pest was liberated.

Carl Lutz was able to count on the backing of his various superiors. The Swiss legation, to which Lutz’s division was attached, was located in another part of Pest, at Stefánia út. After being bombarded in early July, the legation’s chancellery was transferred to the Palais Esterhazy in Buda at the instigation of Count Esterhazy himself. Maximilian Jaeger (1884–1958) had been the minister in charge of the legation since 1938. However, he returned to Switzerland as a mark of protest following the seizure of power by the Nyilas. His replacement, Anton Kilchmann (1902–1961), asked to return home for reasons of health.

Harald Feller (1913–2003) from Bern was then appointed head of the legation on 12 December 1944. He also hid a dozen Jews in his residence and had to evacuate four Swiss women of Jewish origin who had lost their nationality after marrying Hungarians. In January 1945, the Soviets arrested Feller and held him prisoner in Moscow. The Federal Political Department7 ordered an inquiry to determine the motives for his detainment, especially since diplomatic relations between Switzerland and the Soviet Union had been broken off in 1918. The entire staff of the Swiss legation in Budapest, including Carl Lutz8, was questioned on this issue. Harald Feller was repatriated in the spring of 1946, along with four other members of the Swiss diplomatic and consular corps who had been taken prisoner by the Soviets.

The ICRC, which had a permanent delegate in Budapest from autumn 1943, also worked to assist the Jews9. Following the German occupation, the delegation, which eventually numbered 250 members, was placed under the leadership of Friedrich Born (1903–1963). Its activities were threefold: supplying material aid, running homes and hospitals (especially for children), and issuing protective letters.

The Hungarian government allowed Born and his staff to deliver food parcels to Jewish deportees in the concentration camps at Kistarcsa and Sárvár, and to those imprisoned in the ghettos. The Joint Distribution Committee and other relief organisations were pivotal in providing the funds required to purchase the food, clothing and medicines to be distributed. This task fell first and foremost to “Section A” of the ICRC delegation, established in September 1944 with the remit of protecting and rescuing persecuted Jews. At its head, Born appointed Ottó Komoly, Chairman of the Zionist Federation in Hungary, who would eventually be killed by Arrow Cross militia at the start of 1945.

Friedrich Born and his team were especially tireless in their efforts to save children whose parents had been deported or had gone missing. He succeeded in getting the Hungarian authorities to recognise the extraterritorial status of the buildings in which these children were housed in addition to the homes he and his team set up. In total, more than 150 establishments (homes and shelters, hospitals, community kitchens, food repositories and the apartments of those Jews who worked for the delegation) were placed under ICRC protection. This figure includes 60 children’s homes, which accommodated 7,000 youngsters. Nyilas gangs attacked protected hospitals. Born intervened personally, insisting that the buildings’ extraterritorial status be respected, but was unable to prevent the massacre of 130 patients and staff in the hospital at Városmajor utca.

Finally, in September 1944, Born also began issuing ICRC protective letters—30,000 in total according to his own report. He distributed them first to his Jewish colleagues, then to anyone who could claim any kind of link whatsoever to the ICRC delegation and individuals with certificates permitting them to enter Palestine.

Carl Lutz (1964), Gertrud Lutz (1978), Harald Feller (1999), Peter Zürcher (1998), Ernest Vonrufs (2001), and Friedrich Born (1987) have all been honoured with the title of Righteous Among the Nations. Yad Vashem has recognised three other Swiss nationals for their activities in Budapest, including Sister Hildegard Gutzwiller (1995), Mother Superior of the Sophianum, a Sacred Heart Convent whose walls offered refuge to 250 people; industrialist Otto Haggenmacher (2003), who agreed to house thirty Jewish children in his villa and pay for their upkeep; Eduard Benedikt Brunschweiler (2007), an ICRC member in charge of a monastery just outside Budapest in which he set up a children’s home.

4. The rescue activities of Carl Lutz and his team10

The actions of Carl Lutz and his team differ from those of the other neutral actors in two very specific ways. Firstly, they were prompted by Switzerland’s representation of British interests in Palestine. And secondly, they resulted in a Jewish organisation—the Jewish Agency for Palestine—not only being placed under Swiss protection, but also being given its own premises, known as the “Glass House”. These two factors explain why the actions of Lutz and his team were both pioneering—paving the way for those of the other neutral countries—and more extensive.

A highly complex operation was set up in March 1942 to enable Jewish children living in Hungary to emigrate to Palestine. The principal actors were the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem and its Budapest office, the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office and its representations in Palestine and Switzerland, and the Swiss Federal Political Department and its representation in Budapest, all of which were involved in one way or another in drawing up lists of children and/or obtaining the authorisations required for their departure and safe passage. In Budapest, this operation led to regular, close cooperation between Moshe Krausz, who ran the local branch of the Jewish Agency, and Carl Lutz and their respective teams. According to Theo Tschuy, up to 19 March 1944, about 10,000 children would have been able to leave the capital and find refuge in Palestine.11

The German occupation of the country brought this totally legal form of emigration to an abrupt halt, creating two specific problems. Firstly, thousands of Jews in possession of a certificate permitting them to enter Palestine (Palestine certificates) now saw their chances of obtaining an exit visa reduced to zero. Secondly, Krausz and his team found themselves subjected to direct threats. At the start of April, Lutz managed to gain exemption from forced labour for all holders of such certificates and provide them with shelter in his offices at the former US legation. With the backing of the head of the legation, Lutz spent several weeks negotiating with the Germans (first Veesenmayer, then Eichmann) and the Hungarians to ensure that the holders of Palestine certificates would be able to leave Hungary. An agreement in principle was ultimately reached. Thus it was that on 26 May, the Hungarian Council of Ministers approved the emigration of 7,000 Jews to Palestine under Swiss responsibility and of several hundred Jews to Sweden; the Jews under Swiss protection, however, were never able to leave Hungary.

Carl Lutz developed a number of operations and strategies on this basis. These processes often developed in parallel, resulting in contradictory information, especially as far as the number of people involved is concerned.

He requested authorisation to issue protective letters (Schutzbriefe) to individuals who had been granted Palestine certificates. These letters, featuring the Swiss flag and name of the division for the representation of foreign interests, bore an official stamp and confirmed that the bearers had permission to emigrate and that their names appeared on a collective passport—a legal ruse to which we will return presently. It is not possible to determine the exact date from which they were issued and, above all, distributed. Two things are certain: First of all, that the rise to power of the Nyilas sent the production of these documents into overdrive. Secondly, large numbers of forgeries began circulating, some containing basic typographical errors that made them very easy to spot. The number of fakes and of letters being produced at a volume that did not match those of the Palestine certificates increased the risk of the Hungarians and Germans calling the entire operation into question. In November, Carl and Gertrud Lutz were forced to single out holders of forged documents in a brick factory at Obuda in order to prevent all the bearers of Swiss protective letters being condemned to forced marches.

As with the documents produced by the other neutral states, it is impossible to establish the exact number of Swiss protective letters. Figures in excess of 100,000 have been mentioned but do not appear entirely credible. Several tens of thousands would seem a reasonable assumption. One thing that is certain is that Lutz authorised the production of protective letters which were not covered by Palestine certificates. As the protective documents were numbered, care was taken never to exceed the allotted quota—consequently, several letters bearing the same number would be issued.

From the summer of 1944 onwards, Lutz took the stance that the number of emigrations for which he had requested authorisation (some 7,000) and obtained agreement in principal from the Hungarian and German authorities was to be interpreted as applying to families rather than individuals. He subsequently confirmed having authorised 50,000 protective letters to be issued on this basis.

The text of the protective letters makes reference to Kollektivpässe—i.e. collective passports. These simplified the administration involved in arranging the emigration and transit through Romania of the holders of Palestine certificates, and featured both the names and photos of the individuals concerned. Young Jews placed under Swiss diplomatic protection were entrusted with producing these passports, the first of which were issued at the end of July that year.12 It goes without saying that the names included on the list were much lower in number than the holders of protective letters.

In July, Lutz persuaded Hungary to let the holders of protective letters move into special safe houses that enjoyed diplomatic immunity. These buildings, along with those assigned to the other neutral powers and the ICRC, were to become the heart of the “international ghetto”. The new Hungarian minister of foreign affairs ordered all the holders of protective documents to be consigned to this area on 10 November. Of the total 122 safe houses run by the neutral countries, Switzerland was in charge of 76, in which it harboured around 15,000 people. The diplomatic protection afforded these houses was both violated and threatened with violation on several occasions, forcing Lutz and his colleagues to step in. Food supplies were essentially safeguarded by the Chaluzim, young Jewish pioneers, with the active support of Gertrud Lutz.

The arrangements referred to above were developed in relation to the—legal—departure of Jewish children for Palestine from 1942 onwards as part of Switzerland’s representation of British interests. As previously mentioned, the actions of Lutz and his team were unique in another respect: the offices and personnel of the Jewish Agency for Palestine were placed under Swiss protection. Lutz permitted Krausz and his 30 or so staff to work in the Swiss offices at the former US legation. The ever larger crowds that now began amassing on Szabadság tér in search of protective documents brought with them the risk of reprisals—by the Germans or Hungarians—against a building that Switzerland had undertaken to protect. An alternative solution was required.

This came in the form of the “Glass House”, the empty showroom of a glass factory in a neighbouring street, Vadász utca 29 that belonged to businessman Arthur Weisz. Lutz suggested that Weisz work in Krausz’s office and that Krausz relocate to the Glass House, which was to become an annexe of the Swiss legation thus enjoying the same diplomatic immunity. The businessman accepted and the Hungarians gave the project the go-ahead. And so, on 24 July, what was to become the “Emigration Department of the Swiss Legation” moved into the former factory premises.