Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Bedford Square Publishers

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

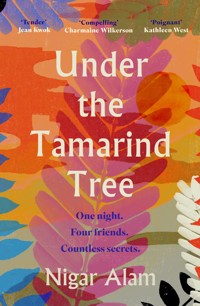

A story of love tested to its limits by moral dilemmas, and the beauty and fragility of childhood friendships. 1964 — Karachi, Pakistan. Rozeena will lose her home, her parents' safe haven since fleeing India and the terrors of Partition, if her medical career doesn't take off soon. But success may come with a price. Meanwhile, the interwoven lives of her childhood best friends — Haaris, Aalya, and Zohair — seem to be unraveling with each passing day. The once small and inconsequential differences between their families' social standing now threaten to divide them. Then one fateful night someone ends up dead and the life they took for granted shatters. Rozeena receives a call from a voice she never thought she'd hear again. What begins as an request to look after a friend's teenaged granddaughter grows into an unconventional friendship — one that unearths buried secrets and just might ruin everything Rozeena has worked so hard to protect. Captivating and atmospheric, Under the Tamarind Tree shows us the high-stakes ripple effects of generational trauma, and the lengths people will go to safeguard the ones they love.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 415

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Under the Tamarind Tree

‘A lush compelling drama… A reminder of how both sweeping historic events and personal secrets can shape lives and continue to reap consequences across the generations’ Charmaine Wilkerson, author of Black Cake

‘Tender and beautifully written… Alam explores class, family and passion in rich cultural detail. A captivating read’ Jean Kwok, author of Girl in Translation and Searching for Sylvie Lee

‘A suspenseful story of friendship, loyalty, and resilience… Alam deftly explores lives ruptured and reshaped by Partition, how historical and personal traumas shape us for generations… A compelling and immersive debut’ Marjan Kamali, author of The Stationary Shop

‘You can practically smell the courtyard’s sweet bougainvillea and feel the Arabian Sea’s misty breeze… Under the Tamarind Tree is historical fiction at its best, a story rich in fascinating historical details and deeply moving as well – a tale of friendship, family, and the power that new, unexpected relationships can have, even late in life, to heal old wounds’ Adele Myers, author of The Tobacco Wives

‘Evocative and rich in detail, Alam’s graceful prose transports you to a rarely seen world and time and leaves you reeling as she reveals its heartbreaking secrets. A beautiful, unforgettable novel’ Aamina Ahmad, author of The Return of Faraz Ali

‘A gorgeous and poignant novel in which Alam explores the fine lines between choice and chance, between the personal and the political’ Kathleen West, author of Minor Dramas & Other Catastrophes

For my parents, whose stories live inside me

Prologue

Nine-year-old Rozeena stared ahead, squinting in the dark at the hordes of shouting people racing toward her family. Were those sticks and spears raised above their heads? Why were they so angry?

Her mother grabbed Rozeena’s wrist and pulled her off the tonga. She landed hard on her knees, but her father didn’t stop to check the bleeding skin below her frock’s hem. Her mother only yanked harder, pulling and dragging until Rozeena got up running. She had to run so fast she had no breath left to ask why they couldn’t go home. Wouldn’t they be safe if they just went back? It wasn’t even far.

The house in front of Rozeena exploded into flames.

Fire leapt into the night sky, and dense smoke entered her nose, scorching her insides. September’s humidity already dripped streams of sweat down her face and back. Now it all bubbled to a boil.

Rozeena spun to her mother. Light from the flames swirled on her face. She stood frozen in place, confusion and fear contorting her mouth into pained twists. Swiveling on her feet, Rozeena searched for her father and Faysal. But they weren’t there. Bodies with bundles of clothing, and suitcases, and children in their arms ran around haphazardly, their screaming faces blurred by darkness.

She turned back to her mother. ‘Ammi, I can’t find…’

But a mass of people was racing toward them now, from the direction of the fire. Every second, the men grew closer and louder as did their thunderous, angry yelling. Why? Her mother didn’t wait to find out. She turned and ran, her hold like an iron cuff on Rozeena’s wrist.

Crowds pushed against them from the front and back, until they ripped right through her mother’s tight grip.

Rozeena was pitched away.

Bodies shoved against her, colliding from all sides as she scrambled to her feet trying to keep her head up, eyes searching. Two women ran toward her, mouths open, arms waving overhead. Were they neighbors? Would they take her to her mother? But instead of stopping, the women charged into Rozeena, throwing her flat on her back. Gasping to catch her breath, she tried to stand up against the wave of bigger, stronger bodies, but her already bleeding knees fell hard on the ground, over and over.

‘Rozee? Rozee!’

Her head shot up. ‘Here! Here!’

She spun around, searching, and saw Faysal. His face grew in size running toward her, the whites of his eyes reflecting the light from the burning house behind her.

‘Rozee!’ he screamed again. ‘Run, Rozee, run!’

Where to? Behind her was the raging fire and the approaching mob, and in front, from a lane across the street, a bigger, even louder group of men emerged.

Faysal pushed her toward the fire, pointing at the house next to it, a safe house where their parents were headed. It would lead to another house, behind it.

‘Another house? A safe house?’

He shook her by the shoulders and aimed her toward it. ‘That way! Just run, Rozee, run!’

Without looking back, she ran like she’d never run before.

That was the last time Rozeena saw her brother.

1

NOW, 2019

Rozeena tightens her fingers around the mobile phone, but it slips down her damp palm. Her other hand flies up to meet it, pushing the phone back to her ear.

‘Your voice,’ she says, a bit breathless. ‘It’s the same.’ She leans forward in her veranda chair, as if it’ll bring her closer to him.

Haaris laughs softly. ‘Well, I suppose it’s the one thing that remains the same, Rozee.’

Her throat constricts at the nickname. Only elders or close friends call her Rozee. At eighty-one, she doesn’t have many left.

‘Is everything all right? Are you all right?’ She frowns at the black-and-white tiles under her slippered feet.

‘Yes, yes. I’m well,’ he says. ‘Just finished breakfast. Around nine o’clock in the morning here.’

In Minnesota. She’s gotten a little news of him from friends of friends over the years and now detects the slight change in his accent, from the British English Rozeena still speaks, to the harder ‘r’ of the Americans in morning here.

Her shoulders relax somewhat at hearing he’s not calling from his deathbed, and she sits back in her polished rosewood chair. She hadn’t recognized the number flashing on her screen when she’d answered the phone. A call with a US country code could’ve been any one of her old colleagues or distant relatives.

But it’d been Haaris.

She realizes the extent of her surprise as she wipes her hands one by one on her kameez. The soft cotton of her long blue tunic absorbs the moisture of her palms, but her heart still races, heating her from within. Reaching down, she plucks away the fabric of her shalwar from the backs of her knees. Her face feels damp as well, though Karachi’s evening breeze is cool as always, even in July.

She hasn’t heard from Haaris in fifty-four years.

Gusts from the Arabian Sea rush toward her, setting the giant palm branches into a powerful spin in the far corner of her garden. She lifts her face to the evening, calming herself to regain control. Silver strands of hair whip in the breeze and she tries to shove them back into her low bun with one hand, but they resist. Let it go, she tells herself, and leaves them to dance on her cheeks.

‘I can hear the wind,’ Haaris says, incredulous. ‘I can actually hear the Karachi wind.’

She smiles. ‘Yes, it’s as loud as ever, but only here closer to the sea. The old neighborhood is congested now, tall buildings and complexes of flats all built up where there were spacious houses.’ Our houses, she wants to say, but instead says, ‘I’ll be going inside soon. It’s past seven o’clock in the evening here.’ She hopes her statement hurries him into explaining why he’s called.

The sun has already dropped low behind the line of tall, pencil-like ashok trees on the right side of her garden. Soon, the call to prayer will burst from loudspeakers at mosques near and far. Five times a day, the azaan thankfully drowns out the continuous buzzing of her neighbors’ air conditioners. Beyond her boundary walls all the new houses are giant two-story, sand-colored concrete boxes made wider and noisier by air-conditioning units clinging to every side. Rozeena’s single-story home, one of the older ones in this newer neighborhood, is well-balanced. The house that lies behind the veranda is equal in size to the garden that lies in front.

‘It’s raining here today,’ Haaris says finally and quietly. ‘It’s not a rainy state, Minnesota. But these days it’s raining inside and out.’

‘Inside and out?’

He exhales audibly. ‘Three months ago, my grandson died.’

A soft gasp escapes her lips. ‘Oh, Haaris, how… I can’t… I’m so sorry,’ she flounders. The death of a child – but not death in general – still shocks her. She remembers that dreadful saying, The smallest coffins are the heaviest.

After a few moments of silence Haaris speaks, his voice conversational again even though Rozeena heard it catch a second ago. Men of his time are masters at bottling up their emotions.

‘Has it rained there yet?’ he says. ‘Or is it waiting for the fifteenth?’

She smiles. He remembers the unpredictable arrival of the monsoon season, unpredictable in its intensity too, sometimes flooding the streets and other times only muddying the dust clinging to leaves. Up north they get the majority of the rains – in the fertile valleys of the Indus River and even further north over the massive Himalayas. But when Karachi does get showers, it somehow rarely happens before July 15. Families can confidently plan all sorts of outdoor events before then, including elaborate weddings.

‘You remember,’ she says.

‘I remember everything, Rozee.’

She searches his words, his tone, his diction. What is he really saying? Does he want her to apologize, or is he going to?

‘But right now, I have a favor to ask,’ he continues.

‘Oh?’ Her guard is up instantly.

‘I have a granddaughter, his sister. Her name is Zara. She’s fifteen years old and in Karachi these days visiting with her parents, my son and his wife. They visit every summer.’ He pauses. ‘Zara says she wants to do something by herself in Karachi, some “good” while she’s there. Her parents of course are scared to let her out of their sight, after her brother.’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘So, we’re trying to find something very safe for Zara to do.’ He takes a deep breath. ‘You remember my oldest sister, Apa, who still lives in Karachi? Well, she mentioned you need a temporary maali.’

‘A maali? How does she know?’ Confused, Rozeena wonders why her servant situation is being discussed.

‘I think Apa heard through a mutual friend,’ Haaris says. ‘You know how news travels.’ Rozeena and Apa don’t socialize directly, but it’s a small world, this city of over fifteen million.

And Haaris’s information is correct. Rozeena does need someone to tend to her garden now that Kareem, who’s worked for her for more than fifteen years, has fractured his tibia. A speeding rickshaw crashed into his bicycle last Wednesday when he was on his way to his fifth house for gardening work. The following morning, the eldest of his six sons arrived at Rozeena’s house, ready to fulfill his father’s duties. Of course she sent the eleven-year-old away, straight to the school in which she’d enrolled him, and with a stern warning not to miss a single day.

How will they be anything but maalis if they don’t go to school? she wanted to say to Kareem that evening in the hospital. But Kareem knew this well and was grateful for Rozeena’s help over the years. Rozeena just hoped that Kareem’s other employers would also continue to pay his wages and keep his family afloat.

‘Since you need a maali,’ Haaris says, ‘I was thinking it would be wonderful if Zara could do the work and be your temporary maali.’

The phone feels hotter against her cheek. Her breath comes faster. Haaris has gone from staying away and silent for more than fifty years to suddenly injecting himself into her life by depositing his granddaughter at her doorstep.

Why?

It’s too close, too dangerous, for herself and for her son.

Haaris explains how Zara would do the maali’s work, and her parents would worry less if she worked in a home like her own grandfather’s. Rozeena stops herself from saying that their homes, like their lives, were never alike.

‘And Apa knows this?’ she says instead, doubting his older sister has agreed. Apa would never sully the family reputation by allowing her grandniece to be a maali, even if just for the summer.

‘Apa will tell herself a comfortable and acceptable version of Zara’s time at your house.’ He pauses, before almost pleading. ‘Will you do it, Rozee?’

She’s too surprised by both his telephone call and his odd request to answer immediately.

‘It would help,’ he continues.

‘I’m certain Apa can find something else for Zara to do.’

‘Yes, maybe. But I don’t know if Zara would agree. I’m not saying she’s being difficult. No, no. Of course I don’t mean that.’ He sighs. ‘But what she’s gone through… Well, you can imagine, can’t you, Rozee?’

She nods into the phone, and Haaris continues as if he can see her.

‘That’s why I want Zara to be with you, under your care. There’s no one else who can help her like you can.’

Rozeena nods again. She has always taken care of people. It’s who she is, even before she was a trained doctor, and even now, years after retirement. But the risk is too high.

‘Most of the people I knew in Karachi have moved out, or moved on,’ Haaris says. ‘Of course you don’t have to agree to this, especially after all the… the quiet of these past years.’

The past is exactly what she fears. It’s what can destroy her little family, crush her son.

‘I can’t do this, Haaris.’

‘Please, Rozee. Please, just think about it. For Zara. For her sake.’

For her sake. For his sake. It’s the past all over again. She pushes it away to focus on practical matters.

‘How long is she in Karachi?’

‘Well, her parents have already taken so much leave from their work this year. Most likely they’ll have to come back to Minnesota before Zara’s summer vacation is over. But then I’ll go to Karachi to travel back with her.’

Rozeena’s breath catches and simultaneously the azaan erupts in the air. Another call to prayer starts within seconds, from a farther mosque. Then another from the opposite direction. Echoes surround Rozeena like old memories rolling toward her.

Haaris is coming back.

She swallows hard, but her mouth remains dry.

He doesn’t speak until the loudest azaan has ended. ‘That was beautiful,’ he says then, and she imagines his eyes closed, his dark lashes long and resting on his cheeks as he listens to the azaan from the other side of the world.

After an entirely sleepless night, Rozeena gives her answer the next morning.

Starting today, Zara will be Rozeena’s maali.

Haaris is grateful, and Rozeena is scared. There will have to be strict rules and schedules, so her son and Zara never meet, so the past has no chance of entering her dear son’s life.

In reply to Haaris’s thank-you, Rozeena types out:

It’s for the child.

She repeats the statement to herself over and over again. Perhaps by bearing the risk to help young Zara, Rozeena will finally be able to atone for what happened fifty-four years ago.

Later that day, after proper introductions are shared, Zara’s parents wave through the rear window of a white BMW as it slowly pulls away from Rozeena’s house. Initially Zara’s parents had been apprehensive, but by the end of the visit, they’d approved of Rozeena, her lone existence in a house with a staff of servants, her past life as a pediatrician, her location so close to theirs, and of course her friendship with Haaris. Zara had nodded at everything her parents said, including how interested she was in gardening, a new but true passion. They’re staying with family only two streets down, but Rozeena notices before they leave that Zara’s parents’ anxious faces and shaky palms seem as if they’re leaving something precious far, far behind.

Rozeena isn’t surprised, of course. They’ve suffered the worst kind of loss already. Their son was in a friend’s car when it happened. All the other boys survived the crash.

She glances up at Zara now, tall like her father, and like Haaris. She wears black leggings under a light pink kameez like girls do in Karachi these days, and her straight dark hair falls well below her shoulders. She looks quite grown up with it parted down the center and framing her oval face. But she waves back at her parents like a child, smiling and swinging her raised arm side to side so it’s visible even from a distance. As soon as the car turns the corner though, her smile fades as her hand falls.

‘Should we go back inside now?’ Rozeena says.

Zara’s eyes are big and brown, also strikingly like Haaris. ‘You can’t even tell it’s a desert here.’ She looks up and down the road. ‘My friends always ask me if Karachi is just, like, sand dunes and camels and stuff.’

They stand in a bubble of abundant sweet jasmine from the thick rows of bushes growing outside all the homes’ boundary walls. Tall coconut palms, ashok trees, and giant neem trees stand inside the walls, some looming over sparkling swimming pools. The street is otherwise empty as it is in the evenings, with only a hint of diesel from the main road where buses honk and rickshaws sputter in the distance.

‘Well, I’m sure you’ve ridden camels on the beach at Sea View.’ Rozeena turns to lead Zara back inside. ‘And it’s certainly a desert here. If I don’t take care, a lot of care, all of this will shrivel up and die,’ she says, stopping inside the gate to gesture at her garden. Her maali does all the hard work, of course, but Rozeena manages it.

Zara joins her at the bottom of the driveway, and Rozeena’s driver, Pervez, pulls the black metal gate shut behind them. Other than the long driveway leading up to the car porch on the right side of the property, the rest of the land is neatly cut in half, with a large rectangular garden in front of the house. A wide wooden pergola juts out from its center above the tiled veranda.

Rozeena cuts across the grass on her way to the veranda and points out plants and bushes that are in immediate need.

‘The organic fertilizer is coming on Wednesday, but before then the water tanker best arrive, otherwise—’

‘They’ll all shrivel up and die,’ Zara interjects, and quickly bites her lip.

Rozeena says nothing until she’s settled in a veranda chair. The change underfoot from grass to tile always requires extra attention. She knows full well the dangers of broken hips at her age. As she smooths her peach-colored cotton kameez over her lap, she pulls the matching chiffon dopatta down to form a V on her chest. The breeze cools her throat as she considers how Haaris’s granddaughter is not really the silent, agreeable girl she was in front of her parents.

As Zara leans back on the other wooden chair now, Rozeena says, ‘What did your grandfather tell you about me?’

Zara shrugs. ‘Nothing,’ and then adds, ‘What did he tell you about me?’

Straight to the point, like Rozeena herself. ‘He told me your brother died. I’m so sorry.’

‘Well, that’s me.’ Zara raises her hand like someone called her name in school.

Rozeena imitates the gesture, not unkindly. ‘Me too.’

Zara’s mouth is open, as if unsure of what to say.

Rozeena shifts in her chair. Even after all this time, it’s difficult to talk about. ‘I lost my brother too, long ago.’

‘Oh, I’m sorry.’ Zara bows her head.

‘Thank you. No one’s ever said that to me before,’ and to answer Zara’s puzzled look, adds, ‘Those were different times.’

She doesn’t say that in those days, loss wasn’t spoken of, perhaps because there was too much all around, and for too many families. Instead of remembering the pain and releasing the anguish, they used that energy to protect whatever was left behind.

2

THEN, 1964

Ten Days Before

Rozeena woke thinking of Haaris. In one more day he’d be back from Liverpool, and then she’d know, or at least begin to discover, what he’d meant by his last goodbye.

The four of them had gathered in Zohair’s garden that night – Aalya from upstairs, Rozeena from next door, and Haaris from across the street – neighborhood friends who might never have met. Three of them had crossed the border seventeen years ago with their families, refugees of Partition who by chance landed here, on short Prince Road. Only Haaris’s family had firm roots in Karachi. Seven generations of amassing wealth had established the Shahs among the powerful elite, their branches spreading past their import/export business and into local government as well.

But as always, that night in Zohair’s garden Haaris was simply the friend they’d grown up with. As he told them he’d be back in only six months this time, his eyes lingered on Rozeena’s. She’d held his gaze, and her breath, until he turned away, slowly.

Now, at the end of the day, Rozeena set the thought aside for the hundredth time. There were more important things. She pulled off her stethoscope and looped it around her neck.

‘Your lungs are clear,’ she said to Gul, Aalya’s maid from next door. ‘There’s no wheeze at all. Are you in any pain?’

They sat facing each other on the only two chairs in Rozeena’s free clinic, the tiny storeroom tucked in the corner of the boundary wall at the back of her house. Gul looked as she always did in her clean shalwar kameez, with her hair in a neat, tight braid down her back.

Aalya’s mother did most of the housework herself and only called upon Gul once in a while for cleaning or washing. It was a convenient arrangement for both since young Gul had no other work. She’d only recently married and arrived from the village to join her husband, Abdul, who was Zohair’s cook in the downstairs portion of the house. Abdul and Gul lived in the servants’ quarters behind the house.

Rozeena’s gaze fell to Gul’s leg which wouldn’t stop bouncing as her eyes flicked around the room. When they hovered on the single window again, Rozeena turned to check it. But there was nothing outside except the night made darker by the tamarind tree, so overgrown it shrouded most of the sandy lot at the back of the house. Even the old wooden swing hanging from the branches was hidden in the shadows.

‘You were having dinner. I shouldn’t have come and—’

‘It’s all right,’ Rozeena said. ‘But tell me, what’s bothering you?’ She planted an encouraging smile on her face, trying to erase the exhaustion Gul must’ve noticed and assumed was from a busy day.

Gul didn’t know that Rozeena had seen only one patient in her new pediatric clinic downtown. She hadn’t told her mother, of course, because one patient meant nothing when every day brought more expenses to the household, the latest being her father’s old car that had started knocking at every left turn. But the blue Morris was still running, so Rozeena avoided discussing the ominous sound with her mother. After the sewage pipe burst last month, Rozeena had noticed a shift in her mother. Uncharacteristic panic had spread across her face as they stood behind the house that day, foul-smelling waste rising from the earth and bubbling up at their feet.

‘We’ll have it repaired,’ Rozeena had said quickly, waiting for her mother’s veneer of strength to return.

Instead, her mother’s spine had curved as if weighted down. ‘How much more can we fix? Soon it’ll be just this, and no house.’ She shook her head at the rising rot. ‘And then Sweetie will have her way.’

It was the first time in years that Rozeena witnessed her mother’s apprehension, and that her mother mentioned the future they’d been trying to avoid since Rozeena’s father died of a sudden heart attack eleven years ago. But now, every new expense could be the final blow, the one that would bring her mother’s brother, Shehzad, but mostly his wife, Sweetie, to their front gate ready to snatch away their life and independence in Karachi.

Because what would people say if Shehzad’s own sister was living in such conditions, with the house crumbling around her?

Shehzad and Sweetie were bent on avoiding any missteps that could cause disfavor among their new crowd. They’d risen in society over the years and had managed to secure a place in the top tier, for themselves and their children. Shehzad ran the Lahore office of Sweetie’s family business, but Sweetie ran Shehzad and their family life, determined to shine worthy of their status in society.

Rozeena and her mother’s downward slide would definitely be a blemish. The only respectable solution would be to swoop in and take them to Lahore.

Until now Rozeena’s mother had refused her brother’s help in order to stay free of the strict expectations that would certainly come with it. For one, Sweetie would’ve arranged Rozeena’s marriage in her late teens or early twenties, like she had for her own daughters. It was the way things were done, she’d say. Girls didn’t need careers. They needed to get married at the right time.

And if Sweetie had her way now, would Rozeena be allowed to work, earn her own money, make her own decisions?

Facing her mother over the rising heat of sewage, Rozeena had insisted she’d have the pipe repaired in no time. Her mother had finally pushed back her slight shoulders and lifted her chin. But after that day, Rozeena noticed her mother’s shoulders curving in whenever she thought she was alone.

‘I took datura,’ Gul blurted now. ‘That’s why you don’t hear anything here.’ She thumped her chest. ‘They say if you light a match to the dried leaves and breathe in just a little bit of the smoke, it helps with the breathing disease.’ Her voice dipped as Rozeena frowned.

‘I’ve told you to stay away from datura.’ Rozeena released a breath to lessen the frustration and fatigue in her tone. ‘It’s not safe. You can even…’ How many times before had she warned Gul?

Whether people called it datura, thorn apple, or jimsonweed, the folklore medicinal plant was a poisonous analgesic and hallucinogenic. Yes, a paste of its crushed leaves could soothe and heal burns. Inhaling the smoke of burning leaves did relax muscles and could rid Gul of an asthmatic spasm. Rozeena didn’t deny the medicinal properties of natural remedies. Many medicines came from plants after all, even aspirin. But regulation was needed, and formulas and dosages had to be monitored.

‘Where did you get the datura?’

Gul bit her lip and shrugged.

‘It came from some hakim, didn’t it? I saw the new store sign in the market. You know, just because a person calls himself a hakim doesn’t mean he studied in a college to learn medicine. Most hakims just cook something up in their kitchens and sell it to you.’

Gul nodded, but Rozeena knew the girl didn’t really believe that these hakims, the doctors of traditional remedies, preyed on the poor and illiterate. To add to the confusion, there were some hakims who had studied homeopathy and pharmacology. People like Gul, however, were bound by access to the closest, cheapest care, which was also the most suspect. That’s why Rozeena offered this free clinic, if only Gul would listen.

But now Gul’s attention was back at the window.

Rozeena jumped up this time and marched over. ‘What’s out there, Gul? What do you see?’

Leaning into the pane, Rozeena squinted in the dark. The loose fabric of her pale blue sari brushed against her back, tickling the inch of bare skin between blouse and petticoat. Cool November air swept over her face, and a prickly shiver ran through her. Something out there was bothering Gul, but there was only the side boundary wall in the distance and beyond that the back of Aalya’s house, rising tall.

Gul leaned right and left trying to get a glimpse out the window, but Rozeena positioned herself directly in front. Folding her arms across her chest, she waited for an answer.

‘I saw something,’ Gul said finally, her voice dropping to a whisper. ‘I saw Zohair Sahib. He was at the bottom of the stairs.’ She motioned toward the spiral concrete staircase clinging to the back of Aalya’s house. ‘I was near my quarters when Aalya Bibi came out of her door, alone, and came downstairs.’ She paused. ‘There are guests visiting for dinner. If they see Aalya Bibi with Zohair Sahib in the garden…’ She didn’t need to complete her sentence.

Log kya kahenge?

What would people say? What would they think?

What was Aalya thinking? Mere gossip could ruin her reputation and her family’s social standing in a second. Rozeena clenched her jaw. Recently, she felt distant from Aalya. She used to know everything about Aalya, as if they were the same person, but now Rozeena felt more and more in the dark with each passing day. Why was Aalya meeting Zohair?

This was Gul’s real reason for banging at the back gate tonight. Confessing about using datura was a filler while she gathered courage to inform on her employer’s daughter. Rozeena was utterly grateful for the information but also had no time to spare. She ushered Gul out of the storeroom, and they exited the back gate together.

‘And remember, no datura. You don’t have any more in your room, do you?’

Gul insisted she was well now and didn’t need any more cures. They reached Aalya’s house in quick, long strides, and as they entered the back gate, shrill laughter sprang into the night. Gul went into her quarters behind the house, and Rozeena hurried along the side of Aalya’s house toward the front garden.

Glancing up at the windows, Rozeena curled her fingers into a fist, bracing herself for the faces that might appear in search of the laughter. She’d curled her fingers the same way holding Aalya’s small hand that first day when they stood waiting for the school bus.

‘Take care of her,’ Aalya’s mother, Neelum, had said, placing her daughter’s hand in nine-year-old Rozeena’s. ‘Aalya doesn’t know these things. How to be in school, how to sit and listen.’

Aalya didn’t even know English yet, Rozeena thought. What would the nuns think? She nodded at Neelum but wondered how many words she could teach six-year-old Aalya on the bus.

‘Promise me,’ Neelum insisted, squeezing the girls’ hands as if she could meld them into one. ‘Promise me you’ll make her just like you, so much like you that people will think she’s your little sister.’ Rozeena’s family had arrived from Delhi a few weeks before. She didn’t know where Aalya’s family had come from, but migrants and refugees were pouring into Karachi from all over, and Rozeena’s father had told her to simply accept and be grateful, and not to pry.

The past was painful for many, and Rozeena knew that well.

This was her chance to start afresh too.

So when the bus arrived, and Neelum released her, Rozeena’s grip had remained tight around Aalya’s hand, vowing to do it right this time.

Now, Rozeena came to a sudden halt. Before her, the garden lay bathed in extra lights to impress the dinner guests tonight. Everything glistened – the water trickling down the three-tiered fountain in the center, the thick grass outlined by pearl-dotted jasmine bushes, the bougainvillea bursting with bright pink flowers climbing up the front boundary wall and arching over the gate like a fairy tale.

And there, in the corner farthest from Rozeena, Aalya stood under the full, dense canopy of the giant tamarind tree, her back turned to everything except Zohair.

3

‘What’re you doing here?’ Rozeena hurried toward them, switching from Urdu to the convent school English of her friends.

Aalya’s thick blue-black waves slid across her back as she spun around. The lights shone on her fingers slipping out of Zohair’s hands. Rozeena froze, shocked silent at this meeting, this relationship she’d never known existed. The way Zohair twisted in place and Aalya wrung her hands, sliding farther away from him, it was clear they’d been keeping it a secret – the first-ever secret Aalya kept from Rozeena.

Looking away to hide the pain and confusion, Rozeena’s eyes fell on the stack of magazines under Zohair’s arm. National Geographic, Time, and Reader’s Digest. She moved closer to read the dates. They looked like the latest issues.

Zohair fidgeted and rolled the magazines into a cylinder, fingers tense around them.

‘Picked them up from TitBit, in Bohri Bazaar,’ he said, his eyes nearly hidden under his brown floppy curls.

Rozeena waited, but he gave no further explanation. Of course they were from TitBit bookstore. But Rozeena had always been the one who bought them to share with Aalya – Archie Comics when they were younger, and then these magazines as they grew older. Zohair had never been interested, until now.

How often was Aalya meeting him here, holding hands, accepting gifts?

A rustle from above startled them, and all three heads turned up to the balcony – where Aalya’s mother and the dinner guests stood staring down at them. Rozeena immediately checked Aalya’s position, but she was thankfully far from the tree. Only Rozeena was close enough to Zohair to hear his rapid breathing. She planted an innocent smile on her face and smoothed her loose hair back into the low bun.

Neelum’s face remained rigid with surprise at seeing her daughter downstairs. ‘I wanted to show our guests the garden from up here.’ Her voice wavered.

‘Of course,’ Rozeena called out cheerfully. ‘It’s the most beautiful one in the neighborhood.’

But the guests still had matching frowns and suspicious squints. Aalya and her family’s future depended on what these two – the bald husband and rotund wife – believed about tonight, and what they shared with everyone tomorrow.

‘I asked Aalya to meet me here,’ Rozeena explained, ‘because I needed my magazines from Zohair.’ She grabbed the magazines from his hands and held them to her chest. ‘He’s so helpful and…’ She pursed her lips. It was best not to prolong this awkward meeting.

Hurrying over to Aalya, she hooked an arm around hers and nodded at the guests before quickly walking toward the side of the house. They ducked under the balcony and waited while Zohair bounded across the garden and into his own house. Above them, Neelum was saying something about all the wonderful people who lived on Prince Road, including Dr Rozeena from next door.

When Neelum and the guests finally went inside, Aalya smiled gratefully. Her cheeks flushed, she swiped at the perspiration dotting her forehead, despite the cool night. Neelum was right about her daughter’s beauty, and about her possible future prospects. Aalya could get the crème de la crème of Karachi bachelors, but now she was jeopardizing it all.

‘Where’s Ibrahim Uncle?’ Rozeena asked. Aalya’s father had missed the entire spectacle.

‘Probably out in the back. He’s planted some mint there too, in a shady spot. You know how he likes plants better than people.’ She smiled.

Rozeena nodded. Technically, it was Zohair’s garden since his father owned the downstairs, but it was Ibrahim’s hobby.

‘Now, about Zohair—’

‘It’s nothing, really.’ Aalya stepped out from under the balcony and crossed the garden.

‘But does Zohair know that?’ Rozeena said, catching up. ‘We all know how he is.’

Aalya’s cheeks turned the deep pink shade of her shalwar kameez, and her large, dark irises reflected light from the sconces flanking Zohair’s front door.

‘You mean, Zohair-with-the-hair?’

They giggled softly, like they were young girls again, and for a moment the air turned sweet, tinged with jasmine from the bushes surrounding them.

‘You know what always surprised me the most about his hair drama?’ Aalya reached down for a skinny stem of leaves that had broken off one of the newly potted mint plants near the tamarind tree.

‘Was it that he got punished over and over again for the same thing?’ Rozeena shook her head. ‘Unbelievable, but he knew what he wanted.’

Every three months Zohair’s school barber would sit him down in the middle of the courtyard, in front of the whole school, and place an actual upside-down bowl on Zohair’s head. The hair below the rim would be chopped off in accordance with hair-length rules at the all-boys school.

‘And we could never convince him to change, to stop caring, to spare himself that humiliating punishment,’ Rozeena said.

She’d tried once when all of them – Aalya, Rozeena, and Haaris – had gathered here in Zohair’s garden to commiserate yet another fresh bowl cut.

‘Get it cut even shorter,’ twelve-year-old Rozeena had told him, feeling wise being two years older than him. ‘Don’t you want to look like a boy? Don’t you want to look like Haaris?’

With tears streaming down his cheeks, Zohair had spun around to her and yelled, ‘I don’t want to look like Haaris. I want to look like me!’

And although Haaris, at fourteen, had seemed much older than Zohair then, he’d nodded somberly in agreement with the sobbing boy.

‘Yes, Zohair knew what he wanted,’ Aalya said now, staring behind Rozeena, at his front door. ‘But what always surprised me the most was that he cried so openly, freely. He was so angry at losing those shiny curls that he just spilled it all out in front of us.’ She shook her head. ‘He’s always himself, even if that person is someone who cries loudly, blubbering like a baby over something that’ll grow back anyway. Isn’t that something?’ Aalya said. ‘There are no hidden parts of him.’

‘We were children then,’ Rozeena said. ‘What did we have to hide?’

Aalya fidgeted with the small, ridged leaves still in her hand.

‘What is it?’ Rozeena said.

She shook her head slowly. ‘I should go. The guests.’ She glanced up at her balcony.

Rozeena wondered if Aalya wasn’t admitting her feelings for Zohair because she was uncertain herself, or because she was afraid of disappointing her mother.

Because Rozeena knew all about expectations and duties.

‘I applied for the National Hospital position,’ she said. ‘The salary isn’t much, but it’ll be regular, and I’ll get some referrals for my new clinic.’ Swallowing, she added, ‘Ammi needs the money.’

Aalya frowned. ‘She does? Why didn’t you tell me?’

‘I’m telling you now.’

Rozeena waited, but Aalya offered no secret of her own, not a word about Zohair.

‘Dawood told me about the position,’ Rozeena continued. ‘Seems like doctors at the hospital hear about these things first. And Dawood is obviously much nicer than his mother.’

They both laughed. No one could deny his mother’s sour temperament.

Rozeena called Dawood’s mother Khala, or aunt, because she was distantly related though there wasn’t much resemblance, in physique or personality, to Rozeena’s mother. But the two women had become close because they had little other family in Karachi. During Partition, their relatives had scattered, settling in Lahore, Hyderabad, and other cities. It was their newfound friendship that had allowed Khala and her perpetual scowl to move into their house soon after Rozeena’s father died. Only in retrospect could they all appreciate the timing of their tragedies. At the time, Khala had needed a home and someone to live with after her divorce, and Rozeena’s mother had suddenly become a widow in need of financial help and companionship.

Rozeena remembers being frightened all the time when her father died, when only half her family was left in the world. She didn’t want to sleep or wake or go to school or stay at home. Fear of another loss had settled in her every cell. Khala’s arrival had somehow slowly shaken that feeling. Or maybe it was the passage of time that had done it. Either way, the new arrangement had suited everyone – two single women, one child to raise, and some money coming into the household from Khala.

‘I know you’ll get the position, Rozee.’ Aalya reached for her hand and squeezed it. ‘Don’t worry. It’ll be all right.’

‘And you? Will you be all right?’

Aalya looked up at the balcony again and spoke quietly. ‘Do you always do what you’re supposed to?’

‘What? Well, yes.’ She frowned. ‘I mean, why not? I think.’ She wrapped her arm tight around the magazines, and her heart thudded against them as doubt crept into her words.

Aalya nodded, unsurprised. She handed Rozeena the mint leaves on their tiny stem, and circled around the other side of the fountain farthest from Zohair’s front door, before disappearing down the side of the house.

4

NOW, 2019

When Zara arrives for her next evening as temporary maali, she’s dressed in jeans and a white T-shirt. Rozeena notices Zara’s thick strapped sandals, the kind her grandchildren used to wear when they’d race to Rozeena from the gate, practically knocking her off her feet with the force of their hugs. But they’re grown up now and much too busy for regular visits.

Zara should be busy too.

Her hair is tied up in a high ponytail, as if she’s ready for work, but she’s been settled on the veranda sipping her lemonade for a while now. Maybe the taste of home has made her too comfortable. Rozeena was careful to use the Country Time mix common in America instead of the usual fresh lemon juice and sugar, because even though she worries about this growing connection to Haaris, she wants Zara to feel comfortable in this new place.

‘I had my driver, Pervez, bring out the hosepipe and attach it in front over there.’ Rozeena points to the coiled pile of lime-green rubber beside the gate.

Early evening is the best time for watering to prevent immediate evaporation, but Zara probably knows that. Apparently, she’s become very fond of gardening.

Zara finishes her lemonade and stares at the grass in front of them. ‘Is this, like, your passion?’

‘Passion?’ Rozeena smothers a chuckle. These young ones speak in such extremes. For now, Rozeena’s new hobby simply fills some hours of the day, a made-up purpose when there’s no real one left. ‘Is it your passion, Zara?’

Her voice is barely audible. ‘Maybe? I don’t know, but it was his.’

‘Fez’s?’

Zara nods and reaches for her phone lying on the rosewood table between them.

It’s all she’s brought with her today, no hat, no long-sleeved covering, no gloves. Rozeena has seen enough well-outfitted ladies in the gardening club she’s recently joined to know how women dress for this work, not that she herself is one of them. She only attends the meetings to learn about plants, so she can instruct Kareem, her maali, better. But after a few gardening club meetings, she surmised that those ladies don’t touch the soil either. They simply enjoy having the proper gear and looking the part so they too can better instruct their maalis.

‘Maybe we can both just enjoy looking at it for now, without worrying about making it a passion?’

Zara looks up tentatively. ‘Really? Yeah, I can do that. Like maybe just take some pics today, for Landscoping?’ She explains how Fez’s blog is not landscaping but scoping, like scoping the land. Her thumbs hover above her phone screen. ‘But it’s not like a real blog. All he did was post pics, and he wasn’t really good at taking them.’ Her voice dips talking of him.

‘Well, then perhaps you can take new photographs, replace the bad ones.’

Zara whips her head around so fast her ponytail almost slaps her face. ‘What? I can’t do that.’

‘Oh? I suppose I don’t know much about blogs and photographs.’ But of course Rozeena knows enough. These days youngsters are much the same across the globe with respect to their phone activities.

Zara stands up, fingers tight around her shocking pink iPhone case. ‘No. I don’t mean it’s not possible, but I can’t change all his work.’ Her voice rises. ‘What would everyone think if I did that? What would they say?’

‘Who?’

‘My parents, my school, everyone who knew him. I’m supposed to keep his blog alive, not just…’ Her voice trails off, and frowning, she steps off the tile and onto the grass.

Poor child. What a burden she’s living with. Rozeena follows her into the garden, and Zara stops in the center to peer at her phone raised to the sky, bright blue and cloudless as usual. When she holds the phone out to Rozeena, it’s a photograph, and it’s breathtaking. Zara has captured Rozeena’s twin coconut palms on one side of the screen, just down to their necks, dark green and full, fanning like spiky giant heads. But the photograph gives the impression of space as well, two lone heads against the vast blue sky stretching all the way to the other side.

Zara smiles shyly at the reaction on Rozeena’s face. The girl knows she’s good, and it’s not just photography for her. It looks like pure joy.

‘Can you write down the name of where all these pictures are? I’d like to see more of your photography. You really are quite talented.’

Zara nods and takes some quick photographs of the bougainvillea covering the front boundary wall before stuffing the phone into her back pocket.

‘I guess I should do the watering now?’

Rozeena would let her skip all the work since Zara isn’t showing much interest, but she seems to need it now, like an unpleasant but necessary chore. A duty, but for whom?

Zara turns on the water and aims the hosepipe at the bougainvillea first. But given the water pressure, the stream is limp, so Rozeena shows her how to cover half the mouth of the hose with her thumb to force a stronger spray. Zara giggles, wincing at random sprays misdirected by her inexperienced thumb.

‘Is it okay to water the flowers?’ she says, once the spray is under control. ‘I don’t want to, like, blow them all off the bush.’

‘Blow them off the bush?’

Zara points to the pink bougainvillea flowers covering the top of the hedge, high on the boundary wall.

‘Oh, those aren’t as flimsy as they look,’ Rozeena says. In fact, they always remind her of her mother, paper-thin and delicate like she’d be swept away by Karachi’s gusts from the sea, but deceptively unwavering.

Zara starts watering the flowers directly, high up above their heads, while the roots of the vine lie at their feet grounded in the bed. Rozeena reaches up to lower Zara’s arm.

‘Let’s focus on the roots today,’ Rozeena says. ‘If there’s dust on the flowers it’ll get washed away when it rains in a couple of weeks.’

Zara’s ears turn red, and Rozeena moves away as if to examine the kangi palm in the corner. She steals a glance, hoping the girl isn’t too embarrassed, but water really is too scarce to waste. As it is, Rozeena pays for weekly tankers to supplement what comes through the city pipes.

Water hits dry dirt and the earthy scent reaches Rozeena as she runs her fingers along the kangi palm’s giant leaves, like rigid, spiky feathers sprouting from the short, shaggy trunk. The leaves fan out to nearly four feet in diameter now, majestic in their perfection, though the slow-growing plant is only thigh high. She planned on telling Zara the story of this beloved kangi palm, and how Haaris had known its ancestor, a memory Rozeena had pushed aside for decades.

But now she admonishes herself for reaching to the past. So much of it needs to stay there. So much of it can jeopardize her present, the life she’s built without Haaris by her side, a good life, a precious one.

After Zara finishes up with the beds around the perimeter, Rozeena says Pervez will water the grass and sends her inside to wash up. Back on the veranda for hot samosas – potato filling is the best kind, Zara says, especially with this tamarind chutney – Rozeena begins to dig for information.

‘Maybe next time you should wear your gardening shoes.’ She points at Zara’s black leather straps and silver buckles. ‘Birkenstocks are quite expensive to ruin in the dirt.’

Her eyes widen. ‘You know about Birkenstocks?’

‘I have grandchildren.’ Rozeena smiles. ‘And they don’t shy away from asking for gifts.’

She doesn’t add that they’re not children anymore, and don’t spend long afternoons at Rozeena’s house munching on samosas, watching movies, and eating as much ice cream as they want. In fact, she hasn’t seen her three grandchildren in months. Adults get busy with their own lives.

‘Have another samosa, Zara.’ Her crunchy bites are comforting.

When Zara finally wipes her mouth with a napkin, Rozeena reminds her to write down the name of the blog.

‘You’re really into everything,’ Zara says, jotting it down on Rozeena’s writing pad. ‘I mean, for being Haaris Daada’s friend.’

Rozeena winces at the word friend. Yes, along with Aalya and Zohair, they’d all been friends once. But Rozeena had lost Haaris along the way.