Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

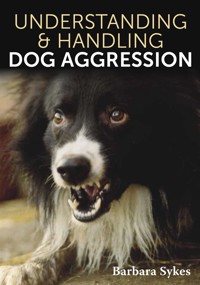

An aggressive dog, whether large of small, baring its teeth and growling can be a terrifying sight. Dogs, like children, require boundaries and training in order for them to grow into sociable, well-mannered adults with a healthy respect for their fellow beings. Barbara Sykes explains how to recognise and understand the causes of hostility in dogs, and how to move forward in a calm and sympathetic way in order to gain a dog's respect and friendship. The author is an experienced dog trainer and her common-sense approach to behavioural problems in dogs is successfully proven in this book by the rehabilitation of Craig.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 197

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 What is Aggression?

2 Recognising Aggression

3 How Aggression Develops

4 Dealing with Aggression

5 Restoring Confidence

6 Recognising Your Capabilities

Epitaph

Index

INTRODUCTION

This book deals with aggression and how to establish a foundation of good manners in a dog. Good manners should not be confused with training. It is difficult to train an aggressive dog and can be demoralizing when you feel that you are not succeeding; but educating a dog to have good manners is essential, comes before training and establishes who is pack leader. It is not always easy to digest what an instructor is saying to you when your dog is misbehaving and so the following pages are to help you to have a better understanding of aggression – in your own time and at your own pace.

No two dogs are alike, so it is essential that you study your dog as an individual thus enabling you to understand his learning capacity and to recognise his problem. Never try to run before you can walk and never confront a dog because you invariably will end up as the loser. I do not usually describe case histories but I feel that in the case of aggression it is helpful as it helps to show the great difference in dogs’ attitudes, regardless of size or breed.

The only references to breeds in this book are to depict examples of size and character and there is no intention to show that any one breed is more or less aggressive than another. The cover dog is not to be seen as depicting his breed as an aggressive one. He was a rescue brought to me for rehabilitation and so it was far easier to record the progress of a ‘resident’ dog throughout to help you to understand how he came to be aggressive and how I handled him and his problems. Craig’s photograph on the cover shows him as he was, but you will see a far nicer Craig at the end of the book.

There are no tricks or treats in the book; it is about aggression and I make no apologies for writing it as it is. I do not believe in wrapping a nasty tasting sweet up in attractive paper to make it more palatable. Aggression is a serious problem, usually instigated by humans, albeit unwittingly. It is important to reclaim the leadership of the pack and to demote the dog to a pack member: if this means admitting that we have made some mistakes along the way, then so be it, we are only human. The first priority is to sort the problem out and not to lay blame, feel defeated or think that you do not have the magical power others seem to have with difficult dogs. There is nothing special about understanding a dog’s mind, we are all capable of doing it, but we have to be willing to see the dog as a dog, realise it has its own form of communication and its own canine instinct. We need to learn how to handle those instincts, not to fight them.

CHAPTER 1

WHAT IS AGGRESSION?

The word ‘aggression’ produces different responses from different people. It does not necessarily need to have been applied to a dog, since aggression is in evidence in every living being and manifests itself in different ways. When used in connection with a dog it often produces nervousness or even fear. We can accept ‘aggression’ in human beings but often fail to see anything but harmful behaviour from a dog classed as aggressive. Yet many dogs are often trying only to protect themselves because they have, albeit unwittingly, been put in a position of leadership by their owners and are not mature or experienced enough to handle it correctly.

If human beings are aggressive we do not immediately picture them as attacking everyone they see; at some stage of their lives we may hope that they will have been taught how to handle any aggressive tendencies they may have and how to deal with anger. If they have not received such education, usually from one or both parents when they are young, then it is possible that their aggression will manifest itself violently and often against another human being. However, correct guidance will help a child or a young person to control his or her aggression and in many cases this will provide the encouragement to redirect this energy into becoming a useful tool, not only for themselves but also to help others.

How can aggression be useful and how can it help one’s fellow beings? If we think of aggression by using another word we can begin to lose some of the preconceived notions of how it will manifest itself; so let us for the moment forget ‘aggression’ and replace it with ‘indomitable spirit’. Now it is easier to understand how this can be both useful and helpful. It is indomitable spirit that keeps the body going against all odds. When fellow humans are suffering through no fault of their own, as in an avalanche, rock fall, shipwreck, or fire, it is the stubborn, ‘never-give-up’ spirit of those people in the rescue bid, using their aggression to combat the elements to bring hope to the stranded.

So are ‘indomitable spirit’ and ‘aggression’ the same? No, but each one is a product of correct or incorrect channelling of certain characteristics as they show themselves in the human being or the young animal. If a child discovers that, by bullying other children, he not only gets his own way but also experiences what could be termed the ‘feel-good factor’ he will continue to keep up this behaviour and, if not re-educated, may become aggressive. However, with sensible adult guidance the child’s behaviour may be redirected into more acceptable forms, for example, competitive sport, then the aggression can begin to work favourably, and, of course, this would be looked on as admirable and not as something harmful.

Appearances may be deceptive; large dogs are often thought to be dominant or aggressive but they are just dogs, many of them are big softies. However someone approaching a dog and thinking that it may be aggressive will transmit his or her nervousness to the dog and this may cause it to react in a defensive manner. The relaxed body language of this dog poses no threat but he is still entitled to his own space.

Appearances may be deceptive and can cause us to judge without any valid reason. A tall, well-built person is often expected to be strong and capable, but a smaller, more delicate-looking one may appear as needing protection. But time spent with these people may prove that the taller person is quite sensitive and the smaller one well capable of looking after him or herself. We are often guilty of judging without any reason other than appearance, and to make a judgement on first sight may cause unnecessary hurt to the individual. This is not to be confused with a person’s ‘gut instinct’: there are times when two people meet and they instinctively like or dislike each other. This is a natural, animal instinct and one that human beings do not always have enough respect for, either in themselves or their dogs. Dogs, like us, have a natural protective ‘space’ around themselves and they often instantly like or dislike an intruder in that space, it may be another dog or it may be a human. This ‘opinion’ will not have been made on just an outside appearance, there will be other factors causing the gut instinct to manifest itself. It could be smell, body language, attitude or any other of a number of possibilities; but the dog will not make a judgement, it will simply protect its space. Humans, however, do judge and if they are basing this on appearance rather than knowledge or instinct they may often judge in error, and, to make matters more confusing, they will often bear a grudge too.

If we study human reactions and then compare how a dog would react in similar circumstances it may make it easier to understand. If a human being has a dislike of a fellow being, it may be the result of an instant judgement, a gut instinct or a private feud. They will not want to be in each other’s company. Should they know that this is inevitable they will become tense at the thought of meeting; they may even begin to anticipate how the situation will evolve. In fact, if care is not taken, what could have been a sensible, adult conversation between two people who have to be in each other’s company for a time may change into an argument whereby little of sense or value is derived from either of them. But the situation can be changed if the people involved control their emotions, curb any aggressive tendencies and either dismiss the meeting from their minds until nearer the time (preventing a build up of negative thoughts) or try to look forward to something positive about the outcome. The point to bear in mind is that they are forewarned, therefore they can control the outcome if they wish. Knowing the meeting is going to take place means that they can either let aggression dominate their feelings and make the meeting non-productive, or they can be sensitive to each other’s feelings, tread with caution and turn what could be a potentially aggressive encounter into something more positive.

This dog’s body is showing signs of tension, the head is dropped and a clear message is being sent that he does not want anyone to enter his space. A dog that is nervous and feels he needs to defend himself may resort to aggression, whereas allowing him to keep his personal space can help him to relax a little.

Animals are not naturally forewarned other than by sight or smell, and so when they see a person they do not wish to be near they do not take that thought away with them nor do they harbour aggressive feelings towards him. But the next meeting can bring about the same feeling of dislike, partly from memory and partly because the basic instinct is still telling the animal to protect its space. But it will be a short-lived reaction: out of sight out of mind, until smell, action or sight triggers a memory. However, dogs are not relying purely on their own reactions, for if they show a dislike of someone or of another dog then their owner will show a reaction. Then an expected meeting with the dog’s current ‘enemy’ will find the handler conveying his fearful thoughts of the possible outcome to his dog, causing it too to become fearful. This fear may then manifest as nerves, aggression, nervous aggression, or a gleeful anticipation of an event to come that is making its owner exude an air of tension and stress.

A dog would meet a ‘threat’, deal with it and then get on with its life. If it were to meet the threat again it would act in a similar way; but dogs in their natural environment would fight for survival, they would not deliberately provoke a threat. Dogs are instinctively pack animals, so in their natural world they would have the support and safety of a pack around them and a strong pack leader to guide them. If their human pack leader is conveying the wrong messages or if he is not credible as a strong pack leader then the dog must make its own decisions. If it is not given the freedom to avoid the space of the approaching threat then it will have to defend its own space and this will be with a show of aggression. Whether nervous or dominant, the dog has made the decision and now it will be wary regarding the threat in future, and it will also have lost any respect for its owner as a pack leader.

At this stage you will be able to see how the natural instincts of the dog would make it react to certain situations and how human reactions can affect the dog’s attitude. The owner’s thoughts transmitted via body language to the dog influence how it deals with a possible threat and can also cause it to harbour a resentment regarding that threat which will surface each time they meet. There is a subtle difference between a dog protecting its space, which is natural if its pack leader does not protect it, and a dog taking a potentially hostile attitude towards a threat because its unsuspecting handler has forced it into a confrontation.

CAN A DOG BE BORN AGGRESSIVE?

There are several reasons why a dog may become aggressive and quite often the problem has been brewing for some time before it is recognised. There are some cases when the aggression is due to breeding, for if a dog with aggression in its genes is bred to another line of aggression then the chances are that at least one, and quite often more, of the young will have aggressive tendencies. Even then it does not have to surface since with correct and sympathetic handling the dog can be educated to subdue its aggression in favour of respect. It is important for all dogs to see their owner as the pack leader, but it is vital that a dog with a dominant attitude and leaning towards aggression not only recognises this leadership but also respects it. It is rare for a dog to be bred so incorrectly that it is beyond redemption and when this does occur it is still down to human error, either through careless breeding or insufficient knowledge of the breed lines being used.

A dog carrying a strong and dominant genetic line can be educated to be a valuable pack member by its handler in much the same way as a sensitive dog can be made either strong or nervous by correct or incorrect handling. If a young dog is sensitive, a potential owner could see it as an attribute, but if a dog is dominant it may be assumed that it could cause problems at a later date. One characteristic is readily acceptable and the other is considered unfavourable yet both are a valuable part of the dog’s character; they just need to be balanced. Everything connected with breeding, training and understanding a dog has to be balanced, and, if the scales are kept as even as possible, the youngster will grow to be a well-adjusted, well-balanced dog. However, if the breeder has not understood the genetics of the dog and has not done a very good job of balancing the breed lines, then balancing must be done after the pups have been born. This is rarely a task undertaken by the breeder since the puppies will have gone to new homes long before they reach adolescence (the age when problems begin to materialise). Also due to the very fact that the breeding has not been done with due care, owing to insufficient knowledge by the breeder, it could even be possible that the youngsters have already enjoyed misusing some of their instincts through unsupervised interaction. So the job of balancing the scales will now rest entirely on the new owner, which may seem an onerous task. However, if the dog is handled sympathetically and, given the correct messages from its owner – the new pack leader – in the early stages, the young dog should reach and enjoy adolescence with hardly any problems.

WHAT ELSE CAUSES AGGRESSION?

The saying goes that there is no such thing as a bad dog, only bad handlers. I agree in part, for a dog is rarely naturally bad, it is usually human influence that causes aggression, but it does put rather an unkind burden on many handlers since they are not intentionally failing their dog. If a handler refuses guidance or is inconsiderate of his dog’s needs, then yes – he is failing the dog. But if a handler in trying to communicate with his four-legged friend is using the wrong language, then he can hardly be considered a bad owner; all that is needed is a common form of communication. Body language can send the wrong messages to a dog, causing it to react in the opposite manner to the one desired by the handler. Correct body language can give a dog a feeling of security; incorrect body language can cause a dog to be nervous.

Small dogs appear cute and harmless; they rarely make people feel nervous, which puts people’s body language at ease, thus transmitting a calm language to the dog. Here the head is relaxed, the body is at ease and the ears are in a gentle position.

But a dog is a dog and just as large dogs may crave a cuddle, so small dogs are capable of being aggressive. In this picture the body has changed, the dog is leaning slightly back to make it easy to propel itself forwards, the head is turned, the ears are erect and the eyes are focusing. He is clearly not happy about something or someone. A small dog may not get the same reaction from a human as a large dog but they still deserve the same respect.

Many puppies are given toys to play with, the intention being to keep them occupied, to prevent them from being destructive and encourage interaction with their owner. Used correctly and sparingly, puppies can benefit from toys; used incorrectly toys can cause destruction and even aggression.

Other dogs may cause aggression; if a young dog is not getting the security it needs from its owner it may feel threatened by the appearance of an approaching, unknown dog.

Children may make a dog feel insecure, and this can lead to protective aggression, as can strangers in the home, sudden unexpected noises and people running. What appear to be simple games, such as chasing, playing with balls or any form of play that encourages the dog to use its teeth, can cause the dormant aggressive instinct to rise to the surface. This does not mean that games cannot be played nor that other dogs, children and visitors must be avoided, but it does mean that there is an onus on the handler to provide the dog with security, good manners and a dependable pack leader.

If a dog enters a home as an older dog or a rescue dog and is showing aggressive tendencies, it will not always be possible to pinpoint the cause, although most dogs will begin to ‘tell’ their owner of their past by simple actions. If a dog cowers or snarls at a sudden movement, a clenched fist or a shuffled boot, then it has obviously received treatment from a human that has caused it to be either defensive or defiant and aggressive. In some instances a dog may seem to be quite passive before suddenly bursting into a show of great defiance that may leave its owner baffled. But to the dog, the smell of after-shave, perfume or even oil or grease can kindle an unhappy memory that triggers a show of aggression.

IS AGGRESSION ACCEPTABLE TOWARD A TOY?

No form of aggression is acceptable but many dogs are allowed, and some are even encouraged, to play in a manner that, to the dog, is the foundation training for aggression. It is not going to cause an immediate problem if a puppy shows aggression toward a toy, but as the puppy develops so will his instinct and if the instinct to use his teeth has been nurtured then he will continue to practise this skill. Each time he ‘kills’ a toy he will gain confidence in his pack skills of hunting, killing and retrieving, and, as all good hunters know, the ‘game’ must get bigger each time.

Respecting a dog’s personal space is important for the safety of both dog and human. This dog is behind a fence and is making it clear he does not want anyone to get any closer.

Here we see how the dog has been pushed into being aggressive. In his mind he is protecting himself and the boundary fence, but having taken just one step closer we can see the change in him. Imagine what would have happened if there had been no barrier. Ignoring a dog’s space and his warning signs can end up with serious injury and a dog losing his life.

Aggression manifests itself in many different ways and it is not peculiar to any specific breed of dog nor to any size. Big dogs are often assumed to be more aggressive than little ones and there can be no argument that if a big dog bites then it can do a lot of damage. But there are many little dogs who look as if butter wouldn’t melt in their mouths and have a temper that is not only aggressive but will often flare up with little provocation. Just because a dog is small does not mean its short temper can be dismissed as unimportant, for although not as strong as a larger dog its teeth will be extremely sharp. Inside every small dog is an instinct to defend and be aggressive to obtain security, just as inside every large dog is the desire for affection. It is how we react to these instincts when they first show themselves that determines the final outcome in the adult dog, for if we fail to recognise them in their embryo stages they will become a natural and progressive part of our dog’s life. When a dog reaches adolescence it will have learned many things about itself, regardless of what we think it may have learned, for its own natural instincts will have been forming as it has developed. If the scales of learning have been tipped unfavourably toward undesirable tendencies they will need to be balanced again before the dog turns a natural instinct into a bad habit.

Throughout these pages we are not looking at certain breeds or sizes of dogs, we are looking purely and simply at an instinct that on many occasions has helped both humans and animals to survive. We are going to see how it can develop, how it can be prevented, how it can be made to work for us and how we can learn to be a pack leader a dog can be proud to be with. We are going to make friends with aggression.

Who Is the Dog on the Cover?

Craig came to me when he was almost two years old; he was the culmination of all the possible scenarios that can cause aggression rolled into one very frustrated, furious and aggressive dog. His breeding left much to be desired, for although his ancestors were all good dogs far too much inbreeding was prevalent in his line. He had been bought as a puppy by a couple in their early sixties who had never owned a dog before. High-energy food had made him hyperactive and the continuous use of his teeth on his abundance of toys had produced a sense of power that he began using on his owners. These problems, combined with pulling on the lead and no recall meant Craig was in full control. He began being not only aggressive to other dogs and people but also to his owners. Craig was an example of what may happen if a dog is not given mental and physical boundaries. A dog allowed to be his own pack leader will make decisions that are not acceptable to human beings; insubordination may manifest itself as bad manners, nervousness or aggression. The breed of dog does not necessarily denote how it will show itself so much as the catalogue of events leading up to its believing it can take control. A very small dog may suffer from dominant aggression and a very large dog from nervous aggression. Throughout this book we are going to watch Craig’s progress and how he turned from being a problem into a pal.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

A dog will often react to the body language of a human being and may see a tense or stiff body as a show of aggression. This may trigger a reciprocal show of aggression from the dog.

If a dog is allowed to be destructive with toys it may stimulate a dominant instinct.