Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

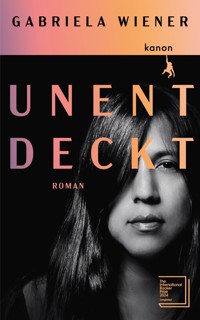

'An intimate story from the family archive, a story that is also the infamous history of our continent' Valeria Luiselli, author of Lost Children Archive'Powerful and searing' Samanta Schweblin, author of Fever Dream A provocative autobiographical novel that reckons with the legacy of colonialism through one woman's family ties to both colonised and coloniser In an ethnographic museum in Paris, Gabriela Wiener is confronted with her unusual inheritance. She is visiting an exhibition of pre-Columbian artefacts, the spoils of European colonial plunder. As she peers through the glass, she sees sculptures of Indigenous faces that resemble her own - but the man responsible for pillaging them was her own great-great-grandfather, Austrian colonial explorer Charles Wiener. In the wake of her father's death, Gabriela begins delving into all she has inherited from her paternal line. From the brutal trail of racism and theft that Charles left behind to revelations of her father's infidelity, she traces a legacy of abandonment, jealousy and colonial violence, in turn reframing her own struggles with desire, love and race. Seeking relief from these personal and historical wounds, Gabriela turns to the body and desire as sources of both constraint and potential freedom. Blending personal, historical and fictional writing, Undiscovered tells of a search for identity beyond the old stories of patriarchs and plunder. Subversive, intimate and fiercely irreverent, it builds to a powerful call for decolonization.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 179

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

UNDISCOVERED

GABRIELA WIENER

Translated from the Spanish by Julia Sanches

PUSHKIN PRESS

In Peruvians, the false imbecility of the body is one with the factual imbecility of the soul.

— Charles Wiener

Embarrassment seems to be the sole means of communication between parents and children.

— Heinrich Böll (trans. Leila Vennewitz)

Death itself can enliven.

— Ludovico Ariosto (as cited by Charles Wiener)

Contents

Part One

The strangest thing about being alone here in Paris, in an anthropology museum gallery more or less beneath the Eiffel Tower, is the thought that all these statuettes that look like me were wrenched from my country by a man whose last name I inherited.

My reflection in the display case mixes with the outlines of these figures with brown skin, eyes like small, bright wounds, and polished bronze noses and cheekbones identical to mine, forming a solemn, naturalist composition. A great-great-grandfather is just a relic in a person’s life, unless the man in question took the not-insignificant sum of four thousand pre-Columbian artifacts to Europe. And his greatest achievement was that he didn’t find Machu Picchu, though he came close.

The Musée du Quai Branly is in the 7th arrondissement, right in the center of an old quay of the same name. It’s one of those European museums that houses large collections of non-Western art from the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Oceania. In other words, a very pretty museum built on something very ugly. It’s like someone thought that painting the ceiling with Aboriginal art and sticking a few palm trees in the corridor would help us feel at home and forget that everything in this place should be thousands of kilometers away from here. Including me.

I took advantage of a work trip to finally visit the Charles Wiener collection. When I walk into a place like this, I always fight the urge to claim everything in it as my own and demand it all back in the name of the Peruvian state—a feeling that only grows in this gallery, which bears my surname and brims with ancient anthropomorphic and zoomorphic clay forms from various pre-Columbian cultures. I look around for a suggested route, a timeline to ground the objects, but they’re displayed randomly, in isolation, their labels vague or generic. I take several photos of the wall with the words mission de m. wiener, just like I did when I went to Germany and felt a dubious satisfaction at seeing my family name everywhere I looked. Wiener is one of those surnames derived from a place, like Epstein, Aurbach, and Günzberg. Some Jewish communities adopted the names of their cities or towns for sentimental reasons. Wiener is a demonym that means “from Vienna” in German. Like the sausage. It takes me a second to realize that the “M.” stands for “Monsieur.”

Even though his mission was just your garden-variety nineteenth-century scientific expedition, at dinner with friends I often joke that my great-great-grandfather was a huaquero of international repute. Huaquero is not a euphemism. It’s how I refer to the looters who to this day remove cultural and artistic properties from archaeological sites. Huaqueros can range from cultured gentlemen to mercenaries, and these ancient treasures can end up in European museums or the sitting rooms of their elegant criollo houses in Lima. The term huaquero, meaning grave robber in Spanish, comes from huaca in Quechua. This is what people in the Andes call their sacred places, most of which are now archaeological sites or ruins. Community leaders and their funerary offerings are buried in catacombs at these sites. Huaqueros systematically invade them in search of tombs and priceless objects, and their incompetence is so great that they leave the sites a complete mess. These violations affect the reliability of subsequent research, making it impossible to reconstruct the past out of traces of identity and cultural memory. Which is why to huaquear is a form of violence. It turns fragments of history into private property that accessorizes and dresses up the ego. Like art thieves, huaqueros are the heroes of Hollywood movies. There is a touch of glamour to their mischief. Wiener himself has gone down in history not only as a scholar but as the “author” of this collection, erasing its real, anonymous provenance with science as his alibi and the financial backing of an imperialist government. Back then you just had to move some dirt around to call it archaeology.

* * *

I wander the aisles of the Wiener collection among display cases crowded with ceramics. One catches my eye because it is empty. The label reads: momie d’enfant, but there’s no trace of a mummy inside. Something about this blank space is jarring. The fact that it’s a tomb. The tomb of an unidentified child. The fact that it’s empty. The fact that this tomb, which has been opened, reopened, and desecrated a thousand times, is part of an exhibit that tells the tale of one civilization’s triumph over another. Does denying a child their eternal slumber tell such a tale? I wonder if the museum took the mummy out to restore it the way paintings are restored, then left the case empty as a nod to the avant-garde. Or if the blank space is a permanent indictment of the mummy’s disappearance, like the time a Vermeer was stolen from a museum in Boston and its empty frame left on the wall so it wouldn’t be forgotten. I consider the theft, the move, the repatriation. Maybe if I wasn’t from a continent of forced disappearances, where people are not only exhumed but buried in secret, the invisible body behind the glass wouldn’t speak to me. But something inside me keeps pushing ahead. Maybe it’s because the label says that the missing mummy was from Chancay, on the central coast of Peru, from the department of Lima where I was born. My head wanders between imaginary graves—small, shallow holes in unreality. I thrust in my shovel and clear out the dust. This time my Incan profile mixes with nothing and for a few seconds my ghostly reflection is the only thing in the glass. My shadow is trapped in the case, embalmed and exposed. Blurring the line between reality and photomontage, it stands in for the mummy, restores it, offering up a new stage on which to interpret death: my shadow, bathed and perfumed, organs scooped out, ageless, like a see-through piñata filled with myrrh—nothing the wild dogs of the desert could eat up or destroy.

Museums are not cemeteries, though they look a lot alike. The Wiener exhibit says nothing about how the missing child died, whether by human sacrifice, murder, or natural causes. There is no mention of when or where. What’s clear is that this place isn’t a huaca, nor is it the top of a volcano where offerings are made to Gods and men, so that the crops are blessed and the rainfall is as constant and heavy as it is in myths, like a shower of baby teeth and the ruby-red seeds of juicy pomegranates that flush through the cycles of life. Mummies don’t keep as well here as they do in snow.

Archaeologists say that children found in the high-altitude volcanoes of South America’s southern tip look as if they’re asleep in their icy graves. They’re so well preserved that at first glance they give the impression they might suddenly come to from a centuries-long slumber and immediately start talking. They’re also never alone. Together, the Children of Llullaillaco were buried in the Andes: six-year-old Lightning Girl, six-year-old Llullaillaco Boy, and fifteen-year-old Llullaillaco Maiden. Together, they were exhumed.

In the not-so-distant past, right here, in this European capital, children were buried beside one another in graveyards—like siblings, or as if a plague had wiped them all out at once and they’d moved into a miniature ghost city within the greater city of the dead, where they could play together if they woke up in the middle of the night. Whenever I visit a cemetery, I like to take a stroll through the kids’ area, sighing and gasping as I read the messages their families left for them in mausoleums and picture their fragile lives and deaths, most of them from minor illnesses. As I stand before this absent mummy, I wonder if our fear of children dying comes from this ancient fragility, if maybe we’ve forgotten our custom of sacrificing them, the routineness of losing them. I’ve never seen the tomb of a contemporary child. Who in their right mind would take their kid’s corpse to a cemetery? You’d have to be mad. What kind of person would bury a child, whether dead or alive?

This child with no tomb, on the other hand, this tomb with no child, has neither siblings nor playmates. Not only that, he is also missing. Had he been here, I could imagine someone, maybe even me, giving in to the urge to grab the Momie d’Enfant—the baby huaqueada by Wiener—wrapped in a cloth patterned with bicephalous snakes and timeworn ocean waves, and making a run for the quay. Leaving behind the museum and racing toward the tower with no concrete plan except to get as far away from this place as possible, while firing a couple of shots in the air.

He didn’t make it, or that’s what people usually say when someone dies, like we’re not the ones always running late and never making it to anything. For several days, my mother refused to admit how serious his condition was, in her usual fashion. Then she finally called and told me to come home, fly now, Gabi, fly, I don’t know how long he’ll hold on. And in fairness, I should’ve known how things would pan out. I wandered around Terminal 4 of the Madrid-Barajas Airport in a daze, preparing for my cross-Atlantic flight with a lump in my throat. By the time I landed, the lump, the intrigue, and my father were gone.

Nothing prepares you for grief, not even all the depressing books I’ve read obsessively over the last decade. I can see Francisco Goldman whispering to a tree on his street in Brooklyn, a tree he believes to be his dead wife Aura, who was killed by a wave. Or David Rieff making a clever remark in the hospital so no one will see how much it hurts that Susan Sontag, his self-absorbed mother, refuses to accept she is dying. I can see Sergio del Molino playing the same song on repeat to ward off his baby’s leukemia. Or Piedad Bonnett telling herself over and over that her son is gone: “Daniel killed himself.” I can picture a cancer-ridden Christopher Hitchens sending everything to hell. Or Julián Herbert navigating the fact that he is the progeny of a dying prostitute. All the books that I read in one sitting, because whenever I put them down, I felt like I was abandoning their authors to face the danger alone, and I just couldn’t bear it. It’s true what Joan Didion said, we all survive more than we think we can. Some survive so one day they can write something no one in their right mind would volunteer to, a book about grief. I could never do a thing like that.

At home, in my family house, I am stunned to find Charles Wiener’s famous book among the handful of belongings my father left me. I recognize the red lettering of the title and of my great-great-grandfather’s name over the brown landscape etching of Cusco. Dad’s phone, which he’d used just a few hours earlier, is also there, as are his glasses, resting on the frayed, yellowed tome. I spend several minutes in the emptiness that my father’s last will and testament ostensibly fills. I don’t reach for his phone right away, as if trying to leave as few fingerprints as possible at the crime scene. My dad just died of terminal cancer in a hospital bed. And now, not wanting to flounder completely, I feel my way around the scattered isles and bottomless pits of his departure. They say that the most populous species in the deep ocean are bioluminescent. I think about this whenever I feel most in the dark. About creatures whose chemical reaction to gloom produces light. I tell myself I can do it, that I’m capable, that if all a mollusk needs is an enzyme and some oxygen to be able to glow and disorient its predators, why not me.

I pick up the book, start thumbing through the end, and come across an appendix I’d never noticed, signed by a certain Pascal Riviale. The title of the piece is “Charles Wiener: Scientific Explorer or Media Man?” The text is brief and almost woundingly sarcastic, just shy of libel. In it, Riviale maintains that Wiener was not so much a scientist as a man with good communication and social skills: “His style, which is at times forceful, or sententious, and deeply humorous—closer to the Romantic lyricism of Marcoy than the scientific rigor of D’Orbigny—is better suited to a salon than a professional setting.” Riviale then quips, bluntly: “His path was laid out: To hell with historical truth! Long live theatrical archaeology!” He was successful, Riviale concludes, because he knew how to curate his public image. I immediately recall an old rumor that is popular among Peruvian academics, one my family refuses to acknowledge. Some scholars claim Wiener was an imposter, a fraud.

I finally turn on my father’s phone. I want to know how he spent his final hours, to spend time with a part of him that hasn’t died. I’m sure most people would find what I’m doing reprehensible, but violating a dead father’s privacy is always relative. He owes it to you. The truth, which is also relative, at least where my father is concerned, is part of my legacy.

I don’t hesitate. I type the name of the woman my father had an affair with for more than thirty years, as well as a daughter out of wedlock. In the first email that comes up, he reproaches her for being unfaithful.

Adultery within adultery.

I put on Dad’s dirty glasses. For the first time in my life—and even more strongly since my late arrival—I feel it’s time I gave serious thought to the notion that there might be something of that imposter in me. And I don’t know if I’m talking about my father or Charles.

The same clichéd, black-and-white photo of a sullen Austrian face sits framed on some random piece of furniture in every Wiener house I’ve ever visited. They say the original has been in the family forever, and that one of my grandfather’s sisters kept it until the day she died.

According to legend, my great-great-grandfather went from unassuming German teacher to Indiana Jones overnight.

My uncle, the one who looks most like the man himself, was inspired to become a historian by his great-grandfather’s exploits. He was the only person in the family to have seen Charles’s book Peru and Bolivia in its original French, in a Parisian library in the eighties. He even looked into having it published in Peru. When the Spanish translation finally came out in 1993, my uncle felt a little disheartened not to have published it himself, but mostly he was excited to finally read it.

The book launch in Lima was a significant cultural affair that brought together the book’s translator, acclaimed author Edgardo Rivera Martínez, as well as former president of Peru Fernando Belaúnde and other illustrious Peruvians. My family attended, proud that Charles’s legacy was finally being recognized. The organizers introduced us to the audience. “We’re honored to be joined tonight by Wiener’s sole descendants in the country,” they said. They had no idea Charles had a son in Peru and that we’d proliferated of our own accord. We could have been a bunch of imposters, but they never bothered to check. The truth is we wouldn’t have been able to prove our relationship anyway. My family rose from their seats feeling for the first time in their lives that their pompous foreign surname might actually be good for something.

The truth is that, beyond the photographs on the sideboards and coffee tables of our nondescript houses, Charles was starting to be recognized in Peru as one of the first European scholars to verify the existence of Machu Picchu, nearly forty years before Hiram Bingham set foot in the country and before NationalGeographicphotographed the monument for the first time, introducing the rest of the world to its beauty. In the black-and-white pictures published in the magazine, the rich green of the mountains is a deep black and the peak of Huayna Picchu is surrounded by immaculate clouds, an intact watchtower, the Temple of the Three Windows, and the intihuatana, or sundial, which tells the exact time. Charles got very close to all this. In fact, he got closer than anyone. At this point I always start imagining how my life would be different if I were actually related to the man who had “discovered” one of the New Seven Wonders of the World, though we all know what it means to discover America and things that have been there all along. Would I have a house with a pool? Would I be allowed to ride the tourist train up to the citadel for free? Would I assert my rights to that piece of land, like so many others have before me since the gringo explorer’s arrival in 1911? Should I have tagged my name on one of the granite walls of the Temple of the Three Windows—just like Agustín Lizárraga, a bridge worker from Cusco who climbed Machu Picchu in 1902, nine whole years before Bingham, only to exit history in a childish, punk gesture of dispossession—as if to say: If it wasn’t for my great-great-grandfather and his little map, I bet you wouldn’t be here taking a selfie, would you?

But Wiener failed. Worse yet, he left clues on his map and an approximate location that helped Bingham reach Machu Picchu, because you never know who you’re working for. “I was informed of other cities, Huayna Picchu and Machu Picchu, and decided to make one final trip east before continuing south,” he wrote of the detour that took him to less important ruins, far from the most extraordinary find in the history of Peru. Missing something by a hair doesn’t make for a good story. In fact, of all the ways a person could fail, this one is especially frustrating. The kind of legacy nobody wants to claim.

Wiener drew a detailed map of the Santa Ana valley based on directions he got from locals, which included trail markers and came very close to the actual route, but then he took a wrong turn and wound up discovering nothing, which meant he didn’t get a medal for stumbling across a monument built hundreds of years ago, or the chance to plant his little flag and sing “La Marseillaise.”

He wasn’t as lucky as his great-great-granddaughter, who in the late twentieth century commemorated the end of her journey by taking a hit from an apple pipe, grateful for the staggering view of the lost city of the Incas, which emerged green and rocky through the fog. All this after walking up peaks that rose 5,000 meters above sea level and down paths through the sacred valley, after several days on the Inca Trail and many kilometers of forest, after sleeping under the starlit sky beside her closest friend, whose tits she was dying to touch. It’s safe to say that despite everything, I made it to Machu Picchu before Charles Wiener. I, quite simply, made it. He did not.

On the back cover of my great-great-grandfather’s nine-hundred-page book, published for the first time in France in 1880, the Peruvian scholar Raúl Porras Barrenechea refers to Wiener, Pedro Cieza de León, and Antonio Raimondi as some of the greatest travelers to have ever graced the Republic of Peru. Fernando Belaúnde points to the “penetrating eye of the humanist” while the historian Pablo Macera asserts that Wiener saw “history more as a vital stance than a method or excuse.” I like Macera’s phrase. If I can’t do anything about having a white European male for an ancestor, then at least give me an adventurer over a doctor honoris causa.

For years my dad treasured this book with its dozens of costumbrista etchings of Indigenous life, keeping it stashed away in a special part of our library. Every time I tried to cozy up to it and linger in its pages, I wound up shutting it in horror. I just couldn’t read it the way so many others did: as a fascinating nineteenth-century travel account. More than that, I couldn’t brush aside Charles’s vile assertions about so-called savage Indians. That man—cruel, violently racist, and blinkered by his Eurocentrism—has nothing to do with who I am today, no matter how much my family has chosen to glorify him.