Unknown Warriors E-Book

13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

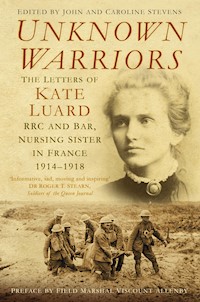

The words of Unknown Warriors resonate as powerfully today as when first written. The book offers a very personal glimpse into the hidden world of the military field hospital where patients struggled with pain and trauma, and nurses fought to save lives and preserve emotional integrity. The book's author was one of a select number of fully trained military nurses who worked in hospital trains and casualty clearing stations during the First World War, coming as close to the front as a woman could. Kate Luard was already a war veteran when she arrived in France in 1914, aged 42, having served in the Second Boer War. At the height of the Battle of Passchendaele, she was in charge of a casualty clearing station with a staff of forty nurses and nearly 100 nursing orderlies. She was awarded the RRC and Bar (a rare distinction) and was Mentioned in Despatches for gallant and distinguished service in the field. Through her letters home she conveyed a vivid and honest portrait of war. It is also a portrait of close family affection and trust in a world of conflict. In publishing some of these letters in Unknown Warriors her intention was to bear witness to the suffering of the ordinary soldier.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

This new edition is dedicated to the Unknown Warriors of the First World War and all who cared for them.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the wonderful people who have contributed to this new edition of Unknown Warriors, for their expertise and support throughout.

Denise Bilton for her speed, skill and patience in typesetting the text as the original 1930 edition and for coping with the numerous amendments as more and more information came to light.

Christine Hallett (Professor of Nursing History at the University of Manchester) and Tim Luard (great-nephew of Kate Luard) for co-writing the introduction: Christine with her extensive knowledge of First World War nursing and Tim who meticulously researched the Luard archives in the Essex Record Office transcribing many of the letters and documents. Thanks are also due to Christine for her help with the glossary.

The Luard family is indebted to Dr Midori Yamaguchi, Associate Professor at Daito Bunka University, Tokyo & Saitama, who inspired us all with her excellent account of the Bramston & Luard families of Essex in her PHD Thesis.

Much gratitude to Tim and his wife Alison with their expertise and experience of proofreading in checking the 1930 text and glossary; and to Tim for all his painstaking research and his valuable contribution to the postscript.

We are indebted to Sue Light, creator of the Scarletfinders website, who unfailingly helped with details of military nursing history and for checking the glossary, also for freely providing her collection of First World War photographs.

Our grateful thanks to Geoff Russell Grant, editor of the Parish News for Birch, Layer Breton and Layer Marney, for supplying Parish archive material relating to KEL and the Luard family of Birch.

Tim Luard and the family are grateful to the archivist and staff at the Essex Record Office, Chelmsford for their help in researching the Luard family papers deposited in the county archives.

Christine Hallett would like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Gertjan Remmerie and Jan Louagie-Nouf at the Archives of Talbot House, Poperinghe, Belgium.

Special thanks are due to my husband John for many hours spent researching and compiling the glossary, indexes and list of personnel and for his invaluable help throughout.

Many thanks to our daughter Louise for all her assistance and support, and for her skills in promoting the book through social media.

Last but not least, a debt of gratitude to my mother, who despite living in Africa all her married life, kept a constant record of family newspaper cuttings, photographs and letters and passed on to us all such respect and admiration for the Luards of Birch.

The help of the following people in providing illustrations for the book was much appreciated: Rob McIntosh, Curator Archives & Library, Army Medical Services Museum, Aldershot; Sally Richards at the Imperial War Museum, London; Miriam Ward at the Wellcome Trust, London.

Thanks are due to The History Press for recognising the value of the work and making it available to a wider public, and for their continued support.

Caroline Stevens

Great-niece of Kate Luard

CONTENTS

Title

Quote

Acknowledgements

Introduction to the New Edition, 2014: Kate Luard (1872–1962) – Professional Nurse and Witness to War

Preface to the 1930 Edition

1 Winter up the Line: Letters from Lillers, October 17th 1915 to April 25th 1916

2 Attacks on Vimy Ridge: Letters from Barlin, May 11th to July 3rd 1916

3 Vimy Ridge – Continued: July 11th to October 12th 1916

4 Battle of Arras: Letters from Warlencourt, March 3rd to June 3rd 1917

5 Third Battle of Ypres: Letters from Brandhoek, July 23rd to September 4th 1917

6 The German Advance: Letters from Marchelpot, Abbeville and Nampes, February 6th to April 6th 1918

7 The Allied Advance: Letters from Pernois, May 13th to August 10th 1918

Postscript

Abbreviations

Glossary

Appendix: Personnel Mentioned in the Text

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

INTRODUCTIONTOTHE NEW EDITION,

KATE LUARD (1872–1962) – PROFESSIONAL NURSEAND WITNESSTO WAR

Unknown Warriors is a long-lost jewel of First World War reportage. Its words resonate as powerfully today as when first written beneath a French sky split by thunderous shellfire and read days later over the breakfast table in a rural Essex vicarage. Since its publication in 1930, it has offered those who have managed to find it on obscure library and archive shelves an extraordinary vantage point from which to view the realities of the Great War: a privileged glimpse into the hidden world of the military field hospital, where patients struggled with pain and trauma and nurses fought to save lives and preserve emotional integrity.

The book’s author, Katherine Evelyn Luard, was one of a select number of fully-trained professional nurses who worked in casualty clearing stations and on hospital trains during the war, coming as close to the battlefront as it was possible for an early-twentieth-century woman to be. This new edition of her book – produced by her own family and offering a fitting tribute to her remarkable work – is a timely reminder of the horrors of war and the courage and endurance of those who survive it. One hundred years after the events it describes, Unknown Warriors provides rare insights into both the experiences of soldiers and the work of nurses.

Having trained as a professional nurse in the 1890s, Kate served the British army in both the Second Boer War and the First World War. By the time she arrived in one of the earliest military hospitals to be established on the Western Front in 1914, she was already a war veteran. Apart from a few weeks absent on leave, she was to remain on the Western Front continuously until 1918.

Although clearly steeped in the values and attitudes of her own time, and fully believing in the right of the Allied cause, she seems to have written with the intention of placing before her readership the full horror faced by war’s wounded. She succeeded brilliantly, and in doing so, managed to convey conflicting messages to her readers, challenging them to view war in new and perhaps disconcerting ways. Such contradictions are familiar to twenty-first-century audiences who honour those who fight in their wars, even as they deplore the havoc wrought and the suffering caused.

Above all, the author’s intention appears to be to bear witness to the suffering of the ordinary soldier. Her ‘Reggie, Walter, Joseph, Harry and Billy, and the armless, legless ones, who won’t tell their mothers’ are real men – often so young that they really seem to be no more than boys. Yet she does not want them to be viewed as victims; rather, she wants us to recognise the nobility with which they endured suffering and met death. Whatever their actions on the battlefield might have been, it is their patient suffering that makes them true heroes. She conveys vividly this sense of heroic endurance.

Kate Luard was not writing for the general public but for her family. She was reporting, in the simplest and most direct way possible, what she saw and heard and felt each day, so that those she knew most intimately could share her experiences. The arrival of her latest despatch, jotted down in pencil last thing at night or whenever there was a moment to catch her breath, was an exciting highlight of her family’s otherwise mostly humdrum wartime existence. Several of Kate’s numerous brothers and sisters, though all well into adulthood, were still living with their father, an elderly clergyman, at his large rectory in the village of Birch, near Colchester. Much of what she wrote had been censored before it arrived, with certain names and numbers and even whole sentences heavily scored out in purplish ink. But what remained was eagerly devoured and – apart from those letters marked ‘Inner Circle’ which were for the eyes of only her most trusted sisters – was passed on around the village and to other family members further afield. ‘You are a lucky devil waltzing to the Front like that… Give our love to the fighting line’, Kate’s youngest sister Daisy wrote to her soon after the start of the war, adding: ‘N and I spend hours reading and sending or copying your cards and letters’.

The family’s shared belief in a man’s duty to fight for his country and their obvious envy of Kate’s privileged position at the cutting edge of the war persisted over the next few years, even as the horror of what she was witnessing became ever clearer and more unremitting. Evidence of their enthusiastic support is found not only in their almost daily letters to her but also in the many presents they sent, both for her and ‘her boys’. These letters in their turn paint a vivid picture of village life in wartime Britain – of the daily struggle to carry on as normal with everything from haymaking to choir practice when almost every man and boy had gone off to fight.

It was Kate’s family who eventually persuaded her to have her letters published for a wider audience. They were printed almost exactly as they were originally written. The present volume remains faithful to the 1930 edition, incorporating the original preface and footnotes, but adds an introduction, a glossary, a postscript and indexes.

Katherine Evelyn Luard was born in 1872, the tenth of thirteen children of the Reverend Bixby Garnham Luard and his wife Clara, who would die in 1907, seven years before the First World War began. The world into which she was born was one in which even middle-class girls had very few career choices. Women were only just beginning to free themselves from a domesticity which had, for centuries, circumscribed their lives.

Kate and women like her, with unflinching determination and a passionate zest for life, broke the boundaries of their time by entering worlds that even a creative mind like Charlotte Bronte’s could not have imagined. They did more than merely step outside their late-Victorian drawing rooms. They took enormous leaps of faith into the worlds inhabited by their brothers; in doing so, they changed those worlds.

The Luard family, of old Huguenot stock, was a close one, imbued with a sense of service to society. The boys were sent to public school and had careers as soldiers or naval officers, doctors or clergymen. (Two of Kate’s brothers, Frank and Trant, were colonels in the Royal Marines, serving respectively in Gallipoli and Palestine, where her letters were sent on to them.) Two of the six Luard girls, Georgina and Rose, went on to graduate from Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

Kate herself attended Croydon High School from 1887-90, where the headmistress, Dorinda Neligan, an active member of the suffrage movement who had served with the Red Cross during the Franco-Prussian War, may have influenced Kate in her choice of career. Kate worked as a governess and as a teacher for about a year in order to raise sufficient funds to pay her way through her probationary periods, first at the East London Hospital for Children and Dispensary for Women; and then at the prestigious nurse-training school of King’s College Hospital, London. Nursing was still viewed in some circles as not entirely respectable. It represented a courageous choice for a late-nineteenth-century woman; but Kate seems to have pursued her training with the same enthusiasm and dedication she was later to bring to her wartime work.

In June 1900 she offered her skills to the Army Nursing Service, and spent two years caring for British casualties of the Second Anglo-Boer War in South Africa. Her letters home are alive with both compassion for her patients and a sense of fun and adventure and give an early indication of her journalistic skills. In April 1902 she wrote to her sister Rose from No. 7 General Hospital, Pretoria, inviting her to share the letter with the rest of the family.

When the afternoon sister comes on at 3, I tear up and change and get on to Ginger. We jump the trench and then go bucketing over the veldt to the tops of Angel Kopjes with heaven born views and Transvaal colours. When you go back on duty at 6 you feel a new man...

Major Holt*, of the Royal Army Medical Corps, often features in Kate’s Boer War letters, normally appearing under the initials MPH or H. As well as being a senior colleague at work, he goes riding with her and they play the organ together in local churches. ‘I may mention he has a fond wife and small boy so you needn’t bother to smell a rat,’ she tells her sisters. ‘But he’s a ripping little man with a rather sad refined face’.

A letter written by Kate from France fourteen years after those first meetings in South Africa suggests the sad-faced major in fact turned out to be the love of her life. Recently discovered among family papers at the Essex Record Office, the letter is in a small envelope marked as being for the eyes only of her eldest sister, ‘G’ (Georgina). It is dated October 21st, 1915:

MPH came in this evening to say Goodbye. He is going to ––––––– tomorrow. Directly I heard that 3 Divisions were going I knew in my bones that he would... He didn’t seem to think we should ever see each other again, but you never know. He said he would have been happy all his life with me. He hasn’t forgotten a single minute of the last fourteen years – that is ours – and the 10 years dead silence was no separation – nor will 50 years be, if he gets killed... He called at the O.H. but I was in the Surgical and met him coming out. So I took him into my little fire-lit office – Goodnight. KEL.

It is not known if he and Kate ever saw each other again.

Apparently undaunted by her experiences in South Africa, Kate joined the Reserve of the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service on August 6, 1914, two days after the British government declared war against Germany. At the time she was working as Matron of the Berks and Bucks County Sanatorium, having previously been night superintendent to the Charing Cross Hospital, London. Now aged 42, Kate was immediately mobilised and posted to France on August 12, 1914. Her subsequent experience of military service was similar to that of other army nurses: she was moved many times during the war, usually at very little notice. Once a nurse had enlisted she was on ‘active service’ and subject to military-style discipline. Leave was granted at the discretion of her seniors, and her work and movements were governed by the demands of the service.

In the autumn of 1914, Kate was posted, first to a British general hospital, then to one of the earliest Allied hospital trains, and finally to a series of casualty clearing stations (CCSs). Her Diary of a Nursing Sister on the Western Front, published anonymously in 1915, recounts these early experiences of the war. The content was drawn from extensive letters, which often took the form of diaries – or ‘journals’ as she called them – and were sent home at intervals to her family as round robins. These were written as if she was speaking to her siblings and were kept throughout her time on the Western Front.

Following Kate’s voyage out to France in a troopship, the SS City of Benares, on 18 August 1914, there was a frustrating period of waiting for orders in Le Havre. But her skills were already in demand, not only as a briskly efficient organiser of nursing staff, billets and equipment (later in the war she would do a spell as a Railway Transport Officer) but also as a linguist.

In due course she was granted her wish to be where the action was. She was moved to Le Mans to attend to the wounded from the Aisne, and, on the crowded ambulance trains she had to deal with the awful results of early battles at Ypres and Neuve Chapelle. Whatever she may have felt at her first sight of such a scene, her actions and descriptions remained calm and measured:

You boarded a cattle-truck, armed with a tray of dressings and a pail; the men were lying on straw; had been in trains for several days; most had only been dressed once, and many were gangrenous... No one grumbled or made any fuss.

There is much in Kate’s letters that is heart-rending, but they never make for grim reading for long. From the horrors of the trenches they move on swiftly: perhaps to the hidden charms of a nearby wood, as their author heads out behind the lines on a rare afternoon off to gather orchids; or, if within range of a new city to explore, she takes us along with her to see the wonders of a French cathedral, where she invariably succeeds in ‘resting her soul’. Sometimes awfulness and beauty complement each other in successive sentences.

She has a genuine interest in and empathy with people for their own sake, whatever their creed, caste or rank. She speaks to wounded German prisoners in their own language, as she does to the French children who are brought in after losing limbs playing with bombs. She is at her ease at a tea party held by the top brass, and equally happy to attend bawdy sketch shows put on by ‘other ranks’. Her letters are alive with direct speech, allowing her to display her ear for dialect and slang.

Even when Kate becomes a Sister-in-Charge and her natural qualities as a ‘no-nonsense’ hospital matron come to the fore, she remains true to the best nursing tradition of getting to know and showing caring affection for every patient. It is clear that the very presence at the Front of British women, sharing the same harsh conditions as themselves, came as a great surprise to almost all the men and afforded them much comfort. While it is true that the nurses were not sharing the extreme danger of actual trench warfare, their units came under frequent shellfire and aerial attack. They often showed great individual courage – as can be seen from a small incident casually recounted in one of Kate’s letters:

A boy with his face nearly in half, who couldn’t talk, and whom I was feeding, was trying to explain that he was lying on something hard in his trouser pocket. It was a live Mills bomb! I extracted it with some care as the pins catch easily.

On October 17, 1915, after four months at a base hospital, Kate was moved to Casualty Clearing Station No. 6, much closer to the battle-lines. By the end of 1916, she had accumulated a wealth of experience in both base hospitals and casualty clearing stations, and was ready to shoulder the responsibility of a position as Head Sister to No. 32 Casualty Clearing Station. The supervision of the nursing care at any CCS was difficult and challenging, but in No. 32 the work was made harder by the fact that the unit specialised in the treatment of abdominal wounds. Such injuries were particularly intractable and, until the middle years of the war, the vast majority of patients who received them died. Indeed, until the spring of 1915 men with severe abdominal wounds had simply been given morphine and put to one side to permit the time and expertise of surgeons to be devoted to cases considered more likely to survive. Now, Kate was in charge of the nursing care in the most important ‘Advanced Abdominal Centre’ of the war. It also became one of the most dangerous when the unit was relocated, in late July 1917, to an area in Brandhoek to serve the ‘push’ that was to become known as the Battle of Passchendaele.

At the height of the Battle of Passchendaele, Kate had a staff of forty nurses and nearly 100 nursing orderlies (the normal nursing workforce for a CCS was 7). As well as doing her rounds of the wards and generally keeping up standards and spirits in the face of floods, mud and shells crossing overhead, a matron had a limitless number of other tasks to attend to. Her duties included organising the Mess, which involved tracking down supplies of such things as fresh milk in the war-ravaged and largely abandoned countryside that surrounded most of the temporary clearing stations. She also took it upon herself to write daily letters to many of the patients’ families. Occasionally these ended on a joyful note of recovery but all too often they involved the breaking of bad news.

Kate’s time in the Ypres Salient was clearly an intensely stressful one, and the comfort she gained from her visits to Talbot House, a rest home for soldiers in Poperinge on the Western Front, made a huge impression on her. Kate was one of the first communicants, climbing the steep, almost perpendicular wooden stairs to the tiny chapel built into the roof of the house. Her friendship with its founder Chaplain ‘Tubby’ Clayton outlasted the war and in 1922 she set up, with others, the ‘Toc H League of Women Helpers’. Religion was clearly an important element of her life. Although Christianity is not prominent in her writings there can be little doubt that her faith sustained her. As the military nursing historian, Sue Light, has commented, ‘believing that a dying man was going on to a better life, or that your own death was a beginning and not an end, must have been extremely comforting and supportive during such dangerous and stressful years’.

Kate’s commanding officer later wrote that the work done by her unit in 1917 was perhaps the hardest of any clearing station in France. Having already been Mentioned in Despatches and awarded the Royal Red Cross, K. E. Luard became one of the few nurses to receive a bar to her RRC. She was decorated by the King at Buckingham Palace on May 8, 1919.

Kate Luard was an independent woman, who travelled to the zone of war, at a time when a woman’s place was believed to be in the home. She was both a professional and an author in a world where female roles were still constrained and feminine voices were almost silent. Yet through the confusion of this world, in which men were sent apparently so casually to their deaths and women were denied professional recognition and political roles, Kate’s voice resonates with truth and clarity. A remarkable piece of witness-testimony, Unknown Warriors is both a vivid and honest portrait of war’s wounded, and a chronicle of women’s work, revealing the true significance of nurses’ frontline contributions. It is also a remarkable portrait of family affection and trust in a world of conflict.

Readers of today will be accustomed to viewing the First World War as something in hazy black and white or muted tones of sepia. Kate Luard’s writing allows us to see it as she did, in vivid colour. She shows us the blues of the periwinkles and the French soldiers’ uniforms; the red and white of the church tent; the pink ribbons from a chocolate box that were used to strap a ‘Flying boy’s’ broken leg. She even has a colour – yellowish-green – to describe the sound of a shell as it screams towards you.

Kate Luard’s ability both to capture reality and reveal her own personality through her writing is impressive. Although the content of Unknown Warriors is often harrowing, its style is cheerful and buoyant. Kate’s consummate skill as a writer permits her to offer a portrayal of suffering which, whilst presented through a brightly-coloured lens, is, nonetheless, a genuine and respectful tribute to the heroism of those who suffered, were disabled and died in the Great War.

Christine Hallett

Professor of Nursing History, The University of Manchester

Tim Luard

Former BBC Correspondent and great-nephew of the author

* Sir Maurice Percy Cue Holt (1862-1954), in 1902 a Major in the RAMC in South Africa, then a Colonel in France during the First World War, went on to become a much decorated Major General.

‘And some there be, which have no memorial; who are perished, as though they had never been …

With their seed shall continually remain a good inheritance, and their children are within the covenant …

Their seed shall remain for ever, and their glory shall not be blotted out.

Their bodies are buried in peace; but their name liveth for evermore.’

Ecclesiasticus XLIV

PREFACE

BY FIELD-MARSHAL VISCOUNT ALLENBYGCBGCMC

These extracts from letters written by a Nursing Sister serving in France from 1914 to 1918 give a stirring account of her experiences in the War Zone.

It is a tale of heroism, modestly told, but unsurpassed in interest by any War novel yet written.

When I commanded the Third Army I had the good fortune to meet the Author on a visit paid to her Casualty Clearing Station during the later stages of the battle of Arras.

I remember well those days and nights of bitter fighting, and how crushing was the burden which fell upon the gentle women who tended our wounded. I look back, still, with admiration on the amazing endurance and self-sacrificing devotion of those Nursing Sisters in their work of mercy.

The Author describes this work in simple unaffected language – language which nevertheless reveals the strength of character that enabled her to bear the strain.

Miss Luard does not hide from us the pain and the cruelty of War; but there is no attempt to shock or horrify. Rather, she attracts our interest in her work at the same time as she enlists our sympathy for the broken heroes to whom she ministered with such loving care.

And, in all the misery of her surroundings, a golden vein of humour sustains her; an appreciation of what is good in life, though standing under the Shadow of Death.

Here are two extracts from the Letters:

May 8th

‘I am engaged in a losing battle with gas gangrene … a particularly fine man too … it is horribly disheartening. When they have been lying out so long G.G. is practically a certainty.’

May 9th

‘And what do you think we’ve been busy over this morning? A large and Festive Picnic in the woods, far from gas gangrene and amputations … my chosen spot – on a slope of the wood, above the babbling brook, literally carpeted with periwinkles, oxlips and anemones… . When we got back … we took the places of the Sisters who had been minding the wards and they went to hear the Band. My dear man was dying. At the exact moment that he took his first breath in Heaven at 7.30 the Band was playing ‘There will be such wonderful things to do’ to that particularly plaintive little tune. His only attempt at a complaint was to say once when I said good-night to him, ‘I wish you were going to stay with me all night.’ ‘

Again, in the year of Victory – 1918 – on the 9th August, at 4 a.m., is this entry:

‘All is ready for Berlin. I’m hoping breathlessly that they hold back my leave to see this through.’

Map drawn by K.E. Luard

1

WINTER UP THE LINE

OCTOBER 17TH 1915 TO APRIL 25TH 1916 WITHTHE 1ST ARMY (SIR DOUGLAS HAIG)

LETTERS FROM LILLERS

During the early months of the War, from August 1914 to May 1915, the writer was engaged in Hospital Train and Field Ambulance work in different parts of the Western Front.

In October 1915, after four months at a Base Hospital, she was sent up the line to take charge of a Casualty Clearing Station. The following letters begin at this date.

Sunday, 9 p.m. October 17th 1915. Lillers, France. This is written by a lovely fire, in an empty Officers’ Ward, in an Orphanage, after a hot water wash, my hot bottle filled, the bed made and turned down by an attentive orderly who nearly waited to clean my teeth for me! I am sleeping here to-night, as the departing Sister in Charge from whom I am taking over this Casualty Clearing Station, and whose billet I shall have in the town, does not leave till to-morrow.

The Orphelin’s French bed looks very inviting.

October 18th. The Sister has been showing me round and handing over her books and keys of office, and has been telling me the ins and outs of it all. There is an Officers’ Hospital in this Orphanage, which I do myself – with a Staff Nurse and two good orderlies. This is up a cobbly slum, full of soldiers’ billets, leading into the usual Square – called the Grand Place. Then there’s another branch in another street, where the operating theatre and the surgical wards are: School Rooms, with the stretchers on trestles. Now only the worst cases are left, who can’t be moved. The trains ‘clear’ the movables and walking cases every day. There’s another place like it for the Medicals, and yet another building where the C.O.’s office is, and my office next door and the dispensary, etc. The Sisters are billeted about in ones and twos, and mess together in a little squashy house, where the people also do laundry work.

This town is rather like Béthune, only not quite so big and rather farther away from the trenches. It is packed with troops and various Headquarter Staffs.

After the yards of red tape one has been tied up in lately at the Base, there is a refreshing sense of freedom and common sense about this sort of work, but I expect it has its own difficulties. The poor lads in their brown blankets and stretchers looked only too familiar. When there is a rush, the theatre Sister and I stay up at night as well. After the 25th (Loos) they overflowed into all the yards and places. The C.O., the Padre and myself are the only people allowed to do the censoring. I do it for the Sisters. I shall have to be very careful myself, not to mention names, numbers passing through, regiments, plans, or anything interesting. We take it in turns to ‘take in’ with Béthune, Choques, and another C.C.S. here – one in four turns.

Monday, 10.30 p.m. October 18th. Just got to bed after my last round. The same old murderous thud, thud, thudding is going on still, along the same old spot, but we aren’t near enough to hear the crackle of the rifle-firing, or see the star-shells and the searchlights and the flashes of the guns, as we used to do.

I spent the morning in the Officers’ Hospital and the afternoon and evening in the Infant School, where the men are; they are busy there to-day – with new bad cases, old bad cases and operations. It seems to be quite as well done as it could be in existing circumstances, but it makes you all the time wonder, more than ever, the Why of it all, and the When it will end.

One officer of the 3rd Grenadier Guards, with an absolutely stricken, haunted face and a monotonous, toneless voice, has been telling me things that make you see the horror of War, and smell it and feel it, over and beyond the wreckage that one handles in the Infant School. He was crawling along a four-foot trench, close to the enemy lines, when they heard a weak voice calling, ‘Come and help me.’ They reached him at last – a man wounded in the thigh, who had been there since Tuesday and this was Sunday. While they were dragging him back, he was all the time apologising for giving so much trouble! These are the people from the Hohenzollern Redoubt.

Went round the Sergeant-Major’s Walking Case Divisions this evening – rows and rows of stretchers, with quite a cheery lot, drinking hot cocoa and reading where there was enough light: they were in class-rooms and places round an open yard, where they cook and brew in large boilers. All the stretcher cases, i.e. lying-down cases, are in my charge, and are called Sisters’ Divisions.

Thursday, October 21st. All last night a Division was entraining at the station and rumbling unceasingly over the cobblestones past the house. A boy is lying smiling all day with his head, right hand and both legs wounded, and his left arm off. When asked ‘Are you happy?’ he said with a beam ‘Tryin’ to be.’ To-day he is humming ‘Sister Susie’s sewing shirts for soldiers.’

I happened to go into the Infant’ School this morning, just in time to see a delirious boy, with a bad head-wound, with a large brain hernia, tear off all his dressings and throw a handful of his brains on to the floor. This is literally true, and he was talking all the time we re-dressed the hole in his head. Then we picked up the handful of brains, and the boy was quiet for a little while. He is very delirious and will not get better.

Thursday, October 28th. The weather is beyond description vile, and the little cobbled streets I wear out my shoe-leather on, are a Slough of Despond and a quagmire. The King has been about here yesterday and to-day, and was to have held a very sodden and damp Review a mile away, only he had an accident riding and had to be carried away instead: no one knows if it was much or not. They didn’t bring him to my Officers’ Hospital anyway.

Saturday, October 30th. A boy came in at 6 p.m. with his right arm blown clean off in its sleeve at 2 p.m. He was very collapsed when he came in, but revived a bit later. ‘Mustn’t make a fuss about trifles,’ he explained. ‘We got to stick it.’ What a trifle! He ran from the first to the second trench unaided. The boy who threw his brains on the floor died yesterday, and another is dying.

Sunday, October 31st. This afternoon we took a lot of lovely flowers to the Cemetery for our graves for All Saints’ Day. We had enough for General Capper’s grave and a few other officers, about ten of our last men and three French soldiers. It took all the afternoon doing them up with Union Jack ribbon, and finding the graves. There are hundreds. It was a swamp of sticky mud, and pouring with rain at first.

All Saints’ Day 1915, November 1st. This is the festival of the Tous Saints, when tout le monde follows the Procession from the Church to the Cemetery and puts flowers on all the graves, and there are services and bells ringing all day. There is also rain. It has been coming down in streams and the streets run rivers: but though it damped, it did not check the piety of the bereaved. Anyone old or young who can claim the remotest share in any tomb – however obscure the relationship or however many years ago – does so in deepest black. The orderlies were much distressed at the weather for them. ‘This is a great day for France,’ they said. ‘The French take these things so serious.’

We have had a busy day – still taking in and also evacuating, and then taking in again. They seem to be getting a lot of bomb wounds. The officers were talking about the trenches in the Hohenzollern Redoubt, that begin British and finish up German, and you never know which you’re in. ‘I came round a corner,’ said a Gunner Officer from Essex, ‘and I met a Hun. I had only a map-case – he had a bomb.’ ‘What did you both do?’ I asked. ‘I didn’t wait to see what he did, but I ran the fastest I ever went in my life.’ A Scotch R.A.M.C. officer, who was with his Regiment all through, was talking about the early morning of the 14th, after we had tried to take the H.R. on the 13th. Our dead and wounded were lying so thick on the ground, that he had to pick his way among them with a box of morphia tabloids, and give them to anyone who was alive: tie up what broken limbs he could with rifles for splints, and leave them there: there were no stretchers, and the trenches too narrow if they’d had any. The Guards made three sorties to bring them in, but in getting three, lost so many men, they couldn’t go on. They are taking the Divisions into the Line and out again so quickly that nobody gets on with making the trenches habitable, and in this weather you can imagine the result.

Tuesday, November 2nd. It has rained again all day without stopping. We are wondering who has been sent to the Château to nurse a certain august patient. The ‘damned good boy’ (Prince of Wales) has made himself a great name with everybody. They all call him ‘a stout fellow.’ He visits dug-outs when they’re being heavily shelled, and when he at last says, ‘I think we’ll go back now,’ the rapidly ageing officer in charge of him heaves a sigh of relief and gets him away. He has a passion for exercise and scorches about on a swagger new cycle, with his officer panting after him on an old Government one.

Wednesday, November 3rd. There are signs of another Tag coming, but they are vague as yet. I hope my department won’t break down anywhere if it comes: one has an unwonted sense of responsibility for people and things. You wonder if you have got all your men on the board in their right places: both Sisters and orderlies have had to be rearranged a bit this week.

A lad had to have his leg off this morning for gas gangrene. He says he ‘feels all right’ and hasn’t had to have any morphia all day. You’d think he’d merely had his boot taken off. Some of them are such infants to be fighting for their country. One has a bullet through his liver and tried to say through his tears ‘there’s some much worse than what I am.’

Sunday, November 7th. A little Night Sister in the Medical last night pulled a man round who was at the point of death, in the most splendid way. He had bronchitis and acute Bright’s Disease, and Captain S. and the Day Sister had all but given him up; but at 10.30 p.m., as a last resource, Captain S. talked about a Vapour Bath, and the little Sister got hold of a Primus and some tubing and a kettle and cradles, and got it going, and did it again later, and this morning the man was speaking and swallowing, and back to earth again. He is still alive to-night, but not much more. It will give me something good to put in her Confidential Report to-morrow. You have to send one in to our H.Q. when anyone leaves.

Monday, November 8th, 10 p.m. Dazzling, sunny clear day, but no time to take much notice of it. We began to take in again this afternoon. A dangerously wounded officer among them this time, badly wounded – abdominal – operated on immediately, before he was washed or changed – have only just left him; he may do, but it is doubtful.

There is a very blithe and babbling boy in to-night. He was in the Argentine when the War broke out – now in the Grenadier Guards. ‘I shall always bless the Kaiser,’ he said, ‘getting me home for this. I wouldn’t have missed it for anything: jolly hard luck on you Sisters though – always having to walk so quietly and all that – we can laugh and shout and swear – it’s not so bad for us.’ I assured him we could do all that out of the wards!

Wednesday, November 10th. It poured terribly yesterday and all last night, and must have made mud pies of the trenches. There are generally about fifteen officers in now, sick – and a few wounded – who are sent down on the trains, except, of course, my abdominal officer, Captain D., who really seems to be going to do. He’s got over the first two days and nothing has gone wrong – and considering the dangerousness of his wounds and the tremendous operation, everyone is very much bucked about him – but it is reckless to boast as early as this.