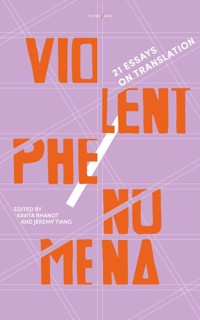

Violent Phenomena E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Tilted Axis Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Frantz Fanon wrote in 1961 that 'Decolonisation is always a violent phenomenon,' meaning that the violence of colonialism can only be counteracted in kind. As colonial legacies linger today, what are the ways in which we can disentangle literary translation from its roots in imperial violence? 24 writers and translators from across the world share their ideas and practices for disrupting and decolonising translation. "For the past few years, I've written and rewritten this line in journals and proposals: literary translation is a tool to make more vivid the relationships between Afro-descendent people in the Americas and around the world." - Layla Benitez James

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 532

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Introduction

Endnotes

All the Violence It May Carry on its Back*: A Conversation about Literary Translation

Endnotes

Bibliography

“Blackness” in French: On Translation, Haiti, and the Matter of Race

Endnotes

The Lion of the Tribe of Judah is Dead!

Right to Access, Right of Refusal: Translation of/as Absence, Sanctuary, Weapon

The Mythical English Reader

Preserving the Tender Things

References

The Combined Kingdom: `Decolonising' Welsh Translation

Bibliography

Seeking Hajar: Decolonising Translation of Classical Arabic Texts

Endnotes

Proust's Oreo

Endnotes

Western Poets Kidnap Your Poems and Call them Translations: On the Colonial Phenomenon of Rendition as Translation

Bibliography

Freed from the Monolingual Shackles: A Mongrel Crônica for the Mutt Translator

Bibliography

Why Don't You Translate Pakistanian?

Translating the Invisible: A Monologue about Translating the Poems of Nagraj Manjule

Endnotes

Deassimilar: Decolonizing a Granddaughter of Assimilados

Translation for the Quaint but Incomprehensible in parsetreeforestfire

Worlds in a Word: Loss and Translation in Kashmir

Endnotes

Translations from Armenian: Reimag(in)ing the Inassimilable

Endnotes

Bibliography

Between the Crié and Écrit

Endnotes

Bibliography

Afterword: Monchoachi's Poetics of Translation (Eric Fishman)

Bad Translation

Endnotes

Bibliography

Considering the Dystranlsation of Zong!

Endnotes

Not a Good Fit

Acknowledgements

Recommended Reading

About the Contributors

Copyright

About Tilted Axis Press

Landmarks

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Interior Title Graphic

Introduction

Introduction Endnotes

Chapter 1

Chapter 1 Endnotes

Chapter 1 Bibliography

Chapter 2

Chapter 2 Endnotes

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 6 References

Chapter 7

Chatper 7 Bibliography

Chapter 8

Chatper 8 Endnotes

Chapter 9

Chapter 9 Endnotes

Chapter 10

Chapter 10 Bibliography

Chapter 11

Chapter 11 Endnotes

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 13 Endn

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 16 Endnotes

Chapter 17

Chapter 17 Endnotes

Chapter 17 Bibliography

Chapter 18

Chapter 18 Endnotes (Monchoachi)

Chapter 18 Bibliography

Chapter 18 Afterword (Fishman)

Chapter 18 Endnotes (Fishman)

Chapter 18 Bibliography (Fishman)

Chapter 19

Chapter 19 Endnotes

Chapter 19 Bibliography

Chapter 20

Chapter 20 Endnotes

Chapter 21

Acknowledgments

Recommended Reading

About the Contributors

Copyright

About Tilted Axis Press

VIOLENT PHENOMENA: 21 ESSAYS ON TRANSLATION

INTRODUCTION

Kavita Bhanot & Jeremy Tiang

In the summer of 2020, in the midst of a pandemic, a large, joyful group of protestors pulled slave trader Edward Colston from his plinth on Colston Avenue, rolled him through the city, and threw him into Bristol Harbour. Four of the protestors were later found not guilty in a court of law, prompting the Conservative MP Scott Benton to tweet, ‘Are we now a nation which ignores violent acts of criminal damage?’

In The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon asserts that ‘decolonisation is always a violent phenomenon’1. He continues: ‘Colonialism is not a thinking machine, nor a body endowed with reasoning faculties. It is violence in its natural state, and it will only yield when confronted with greater violence.’ And indeed, the activists protesting the Colston statue had tried non-violent means, with years of petitions and lobbying.

The toppling, when it came, was a concrete act of collective impatience, a refusal to wait any longer. This anthology represents a similar spirit of defiance and resistance, drawing upon the work, discussions, and struggle of numerous writers and translators over many years, only a small fraction of whose voices are represented here. We have sought to put together a cross-section of a much larger conversation, with a growing number of translators and writers acknowledging that translation is a fundamentally political act, something Aaron Robertson alludes to with his mischievous comparison of ‘the good translator and the good civic actor’.

Like all literature, translation is produced by labour, and is therefore affected by the material conditions of societies and systems. As Yogesh Maitreya writes: ‘Literature in any world language, with translation being one of its facets, has always been a reflection of the dominant community.’ So it shouldn’t be surprising to find life’s inequalities present here too – not only in the text but also the circumstances surrounding the production and marketing of it. We need to name these dynamics and hierarchies, rather than treating literature as an abstract entity untouched by real world structures.

Campaigns to improve the working conditions and stature of translators often focus on incremental change, which is inadequate. On their own, even calls for diversity and inclusion within translation can be tokenistic, a way of preventing or containing the violence of real change, maintaining a comfortable (for some) status quo. Whilst we should certainly be paying attention to who translates and what is translated, especially in a field dominated by middle-class whiteness, we also have to consider ideology and perspective, to ask how a text is translated, why it is being translated, who it is translated for, how the translation industry upholds existing hierarchies. In other words, we have to consider the harm inherent to translation itself.

Translation is often, in Khairani Barokka’s phrase, an act of ‘colonial extractivism’ that presumes a ‘right of access to information’. Many within the Anglophone literary world have an impulse to learn about other cultures and languages that arises from a sense of being ‘above’ the world and wanting to grasp it, leading to an acquisitive approach to translation. This can be traced back to an imperial mindset; Western interest in literature in ‘other’ languages was motivated by a desire or need to better understand their colonies and colonised subjects – to rule, dominate, and exploit. Such translations disseminated this ‘knowledge’ more widely in the West. As Edward Said says in Orientalism:

On the one hand, Orientalism acquired the Orient as literally and as widely as possible; on the other, it domesticated this knowledge to the West, filtering it through regulatory codes, classifications, specimen cases, periodical reviews, dictionaries, grammars, commentaries, editions, translations, all of which together formed a simulacrum of the Orient and reproduced it materially in the West, for the West.

Translation can inhabit a similar role today. The Indonesian translator Tiffany Tsao notes in an interview a ‘dispiriting’ trend on the part of Western readers, whose ‘consumption of Indonesian literature so far is tied up with how much it can teach them about local culture, history, food, feel, etc. Ultimately, literature isn’t a tourist guidebook.’2 At a more institutional level, a translation grant offered by a US university articulates its interest in ‘developments outside the historical West’, as an ‘inquiry into epistemologies and paradigms emerging from societies and spaces beyond the West’. Such phrasing is common, but this seemingly benign ‘curiosity’ can be questioned as an assertion of power. ‘Doesn’t translation act also as unconditional access, as surveillance, as an expanding force of the global capitalist market of literature?’ writes Mona Kareem in her essay.

This imperialist mindset tends to play out within translations themselves. The dominant framing of literary translation suggests that it exists on a spectrum between ‘domestication’ and ‘foreignisation’.

The first approach, in which cultural and linguistic ‘difference’ is absorbed and assimilated, is referred to by Shushan Avagyan as ‘the illusory dictates of the translator’s invisibility, the concomitant domestication of the foreign text and replacement of difference’ turning translation into ‘an act of ideological violence, in which its aim is to bring back a cultural other as the recognizable and the familiar’. This attitude can be traced back to translators such as Richard Burton, who writes in his foreword to The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (subtitled “a plain and literal translation of the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments”):

Holding that the translator’s glory is to add something to his native tongue[…] I have carefully Englished the picturesque turns and novel expressions of the original in all their outlandishness[….] I have carefully sought out the English equivalent of every Arabic word, however low it may be or “shocking” to ears polite…not exaggerating the vulgarities and the indecencies which, indeed, can hardly be exaggerated.

Lest we imagine Burton’s idea of translation as ‘adding to the native tongue’ is an antiquated one, a 2010 anthology of translated work was titled Making The World Legible, making one wonder who the presumed reader of this book might be – someone outside ‘the world’?

The second approach of ‘foreignising’ – maintaining difference to keep the text ‘exotic’ – is exemplified by Sawad Hussain’s description of publishers insisting on ‘a desert scene’ for her book cover. Lawrence Venuti presents this as a more enlightened method than domesticating:

A translated text should be the site where a different culture emerges, where a reader gets a glimpse of a cultural other, and resistancy, a translation strategy based on an aesthetic of discontinuity, can best preserve that difference, that otherness, by reminding the reader of the gains and losses in the translation process and the unbridgeable gaps between cultures.3

While a refusal to domesticate might seem admirable, Venuti’s framing is one of fetishising and othering. The main problem with the domesticating/ foreignising framework, is that it defines translation strategy in terms of difference from a presumed normality. In this paradigm, the ‘mainstream’ perspective is presumed to be a neutral, stable centre – such as the ‘mythical white reader’ of Anton Hur’s essay – against which all translations must be measured.

Given the longstanding, ongoing relationship between translation and colonialism, while we were putting this anthology together, we found ourselves asking if there was a contradiction inherent in the very idea of decolonising translation. (‘What will we talk about next? Decolonising Colonialism?’ asks Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi.)

It’s tempting to draw a parallel in response to ongoing colonial domination: colonial nations once set forth from centres of power to extract labour and resources from elsewhere, their ships returning laden with rare spices. Now the colonised are in a position to say: We are no longer willing to be your spice; we are asserting our own stories, sailing our own ships. But the structures that have formed us, that this anthology has emerged from, are bigger and more powerful than individuals.

Setting out to put together an anthology of essays by translators across the world – searching for, gathering together, presenting these ‘world’ voices (that some may choose to see as representing regions, nations, races, religions, languages and struggles) – felt undeniably colonial at times. This anthology is located within Anglophone structures of publishing and funding; likewise, its editors are limited by the voices (via English) that we could ‘access’ and bring together (and even here, in this framing, in the use of the word ‘access’, the effort to make these voices ‘accessible’, we see glimpses of the colonial legacy we have inherited).

Meanwhile as editors, via different yet overlapping circumstances,4 we have been formed through colonisation and continuing colonial structures of whiteness in ways that we cannot even comprehend. We can’t claim that we’re not colonial or that we could ever fully decolonise ourselves (as well as inhabiting other supremacies of race and gender, religion and caste, class and anti-blackness). The decolonial struggle for self-assertion falls too often and too easily into a binary, which doesn’t account for ongoing layers of power and dominance.

Across these essays we see different strategies employed to resist traditional perceptions of translation and the translator, including questioning the idea of ‘good’ translation, claiming and producing ‘bad’ translation, or, echoing Glissant’s call for the right to opacity, refusing to translate at all. M. NourbeSe Philip and Barbara Ofosu-Somuah analyse how a dystranslation of Philip’s poem Zong! came to be ‘yet another site of unapologetic colonial claiming’, while Elisa Taber speaks of how her translation practice includes untranslating Guaraní terms. Eric Fishman notes in the afterword to his translation of Monchoachi, ‘it’s obvious that Creole is, at the least, resistant’ to accepting ‘the status of a language’ – a further complication to any kind of translation attempt. Hamid Roslan also discusses a Creole – Singlish, ‘hewed from the Chinese, Malay and English’ – and its role in his ‘faithless act of translation’.

Other contributors, by contrast, focus on how translation can make visible the hitherto unseen. Yogesh Maitreya writes about translating Nagraj Manjule’s poetry from Marathi into English, seeing himself in the language for the first time and articulating and communicating this presence to the rest of the world. This is also important to Haitian writer René Depestre who, in Kaiama L. Glover’s words, ‘has long been preoccupied with the power differential that places him on the margins of a world order he has worked passionately to upset’. Meanwhile, an absence of translation can feel like erasure. As Sofia Rehman says, ‘Who knew a blank page could feel so oppressive.’

Above all, this book is a challenge to inherited assumptions about translators and translations being neutral, making the case that every aspect of translation is political. Strikingly, and going against the stereotype of the ‘objective’ translator, none of these essays are dispassionate. From Eluned Gramich’s conversations with her mother to Layla Benitz-James’s culture shock in Spain, there is a strong personal element to most of them; we can’t extricate ourselves from the worlds we translate from or into, even if we want to. These are accounts of translators in the thick of it, so enmeshed in the cultures and languages they are translating between, that neutrality is neither possible nor desirable. Madhu Kaza, whose contribution ‘Not a Good Fit’ charts her tangled heritage language journey, articulates this idea clearly in the seminal Kitchen Table Translation:

[T]ranslation can be an intimate act, and many of us use our translation skills in non-professional as well as professional capacities. Some of us, when we translate, call on our family (rather than colleagues) to help us with challenging passages or words. Some second generation, diasporic and indigenous writers who speak (or partly speak) an ancestral language at home might find the discourse of mastery fraught, especially when access to a language has been lost through historical violence and dislocation. And some of us experience translation all the time in our bodies, names, homes, movements and daily lives even if we are not translating from one text to another.

Gitanjali Patel and Nariman Youssef explore the complicated relationship that the diaspora has (or doesn’t have) to ‘heritage’ languages, a sometimes fraught association that we also see in Onaiza Drabu’s learning of Kashmiri as an adult ‘through a lot of luck, a little bit of effort and a rage inside me’, and Sandra Tamele’s ‘absence of a mother tongue [leaving] a void inside me that I tried to fill by learning foreign languages’. Amid such linguistic complexity, simplistic ideas about only translating into one’s ‘native tongue’ are inadequate, as amply shown in Lúcia Collischonn’s essay.

Even as many of these essays draw from personal experience, they are ultimately about systems. While individual efforts and experiences are important, real change, fundamental change, takes place at the level of structures, and in order to shift these, we first need to see them clearly. Oppressive systems must be dismantled rather than negotiated, in order for new possibilities to emerge, for us to even imagine something else.

Broadcaster and historian David Olusoga, who gave evidence in the Colston trial, later said, ‘The toppling of the statue and the passionate defence made in court[…] makes [a] deliberate policy of historical myopia now an impossibility.’ There is a similar need to address structural inequalities and historical myopia in the publishing and translation worlds because business as usual is no longer possible. We hope this anthology will contribute to that conversation. Colonialism is violence, and it is difficult to see how decolonising could be anything other than a violent disruption.

Endnotes

[

←1

]

Or at least he does in Constance Farrington’s `1963 translation. In Richard Philcox’s 2004 rendition, ‘un phénomène violent’ becomes ‘a violent event’, but we found Farrington’s phrasing more resonant – thus illustrating the importance of translation choices!

[

←2

]

Tiffany Tsao interviewed by Whitney McIntosh, Liminal, 16 November 2020

[

←3

]

Lawrence Venuti, The Translator’s Invisibility

[

←4

]

Kavita Bhanot’s parents are from Punjab, India while she was born and brought up in Britain. Jeremy Tiang was born and raised in Singapore just over a decade after independence.

1. ALL THE VIOLENCE IT MAY CARRY ON ITS BACK*: A CONVERSATION ABOUT LITERARY TRANSLATION

Gitanjali Patel & Nariman Youssef

* The phrase ‘all the violence it may carry on its back’ is used in relation to translation by Madhu Kaza in her Editor’s Note to Kitchen Table Translation, a major source of inspiration for the authors.

London 2019: You’re at a drinks reception after a literary translation event and find yourself talking to two colleagues. It’s unclear whether they are talking to you. Their body language seems to suggest you’re in the conversation, although you haven’t been addressed yet. Heritage languages. Your ears prick up. Here we go. They must be about to ask your name, no doubt they are keen to hear about your... Natural translators. You blush, it’s rare to receive compliments from white colleagues. And what’s in a name, anyway? Raw talent. Does raw mean good? Surely they’re not suggesting all ‘heritage’ speakers have... Need to nurture that. Wait, what? No pride in their heritage. You start edging slowly away from the conversation. Your colleagues barely notice.

Words have the power to distort and misrepresent, to blind us to the unarticulated, to the wilfully or accidentally obscured. Sometimes, our stories are left untold for fear that they would crack, splinter, and break under the pressure of the moulds available for the telling. Or because the words we have at our disposal would leave large swathes of our experiences in the dark. But words also have the power to reimagine and reconfigure. At the very least, they can illuminate some of the hidden corners of our lived experience. Audre Lorde writes: ‘The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives’. Let the stories come as they are then, cracks and all. Perhaps that’s how just the right quality of light gets in.

* * *

The idea of being a professional translator seems strange when it’s a seamless part of what you’ve always done from a young age – back and forth between home (family members) and the world (school, university, doctors, shops, public transport).

One day my mum claimed she wasn’t fluent in any of the four languages she speaks and I haven’t stopped thinking about it since.

As someone who has been writing fiction and poetry in English for over a decade, I first became interested in translation three years ago when I developed a passion for drawing on my Chinese heritage and literary roots to inform my writing. I had been practicing code-switching in many ways already as a writer of the Chinese diaspora, so translation felt like a natural extension of my writing journey.

Even now, I worry that much of the interest in my work as a translator has to do with the novelty of a Black person who somehow stumbled into the field.

I am a writer as well as a translator, which I like to think means I approach language with a lot of intention. I would even go so far as to say that I approach it with more intention than white writers and translators, if only because my claims of mastery over it are always tenuous, always being called into question.

I debuted at the same time as a white translator in the same competition. The white translator kept getting books to translate. I was given nothing.

At some point I started to remove my nationality from my bio and CV. It had become clear to me that the fact that I hadn’t been born in an English-speaking country was hurting my chances of finding work as a literary translator, and in English-language publishing more broadly.

You’re usually one of a few non-white faces amongst translator communities – and others who are not white tend to be from more privileged backgrounds.

I was brought up reading Enid Blyton, despite not setting foot in the UK till I was eighteen.

Sometimes, I feel too foreign for this home. Sometimes, this home feels too foreign for me.

* * *

The world of Anglo-Atalantic literary translation has, for a long time, been dominated by a number of assumptions about who translators are and what translation is about. Translators are presumed to be white. Their English that of the educated middle classes. Their modes of expression and creative processes primarily and unequivocally rooted in the language and tradition into which they translate. They come to learn and read ‘other’languages out of curiosity about the ‘outside’world. Translation is a bridge between two distinct cultures. Literatures are gateways into foreign lands. Translators cross the bridge, step through the gateway and bring back whatever treasures they can carry. Some things might get lost on the way.

These assumptions still dominate the way translation is thought of and talked about in ‘most mainstream literary spheres’. We are centring, in this essay, the experiences of translators for whom such mainstream is not enough.

* * *

Whenever someone asks what my first language is, they get a speech about colonialism and its aftereffects. I’m sorry, did you think that was a simple question?

Not all languages are equal.1 Some take up more space in the world and in our imaginations than others. For English users who have no other language, or none until school or university, it may not be clear how ubiquitous English is, even for those who never use it. Meanwhile, those who come to English as a lingua franca, a language of the world, might never think of it as also a private language. It may be hard to imagine what it’s like to live in a world ‘where all instructions, all the lyrics of all the stupidest possible songs, all the menus’ are in the language you uncomplicatedly call your own. Olga Tocarczuk, not without some irony, posits this lack of a private language to hide behind as a reason to feel overexposed. But it is also a source and signifier of power: the ability to choose when and if you ever want to step outside the comfort of your own tongue.

I am often praised for translating into a non-native tongue, and told by translators that they wish their second language could be as good as my English. What they don’t seem to understand is that English holds a different global status from other languages, and that English wasn’t just some kind of hobby I picked up by choice, but my language of instruction.

Translators are often assumed, or told, to translate into their ‘native tongue’ or ‘first language’. A simplistic rule that not only implicitly prescribes certain parameters of quality—which imprison a lot of translation into the blandest form of literary English—but also presupposes a very specific and narrow relationship to languages in general. A relationship that privileges language-learning on a foundation of monolingualism, discounting the phenomena of migration and the experiences of migrants. One that renders the majority world—where colonial languages prevail—invisible.

The most benign of responses to my source language are the most humiliating. ‘Oh! Wow! Really? Interesting!’ An awkward two-second silence and ten vigorous nods later, the next line is almost always, ‘Your English must be very good!’ That is usually the moment of a thousand deaths.

Not everyone comes to the languages and literatures of ‘others’ out of a conscious move beyond themselves. Reading in multiple languages does not have to be an act of generosity or curiosity; some of us have existed with multiplicity all our lives.

I grew up bilingual and can’t relate when people say translation is a bridge. How can it be, when for me both languages reside in the same place?

Because the anglophone literary translation world2, especially in the UK, is so disproportionately concerned with European literatures —understandably more so in the wake of Brexit—everything else is relegated to a separate sphere, which is seen as less literary, more othered, altogether inferior, labeled ‘heritage’, ‘community’ or ‘minority’.

The experience of grappling with, translating from, your heritage language can be intense and emotional; you have a different relationship to the language – this is something that a non-heritage language translator perhaps can’t relate to.

Translators who work with ‘heritage’ languages are rarely part of mainstream literary translation conversations.3 And those who are invited in can be seen to be doing the service of bringing in ‘outsider’ voices. If a white translator works from a minoritised language, their work is seen to be especially generous, selfless, or adventurous. The same does not apply if the translator is a heritage user of the language they translate from. Then, they are seen as not having had much of a choice. They are seen as examples of raw talent over delicate craft.

You feel as if the language that you’re translating from is in your bones, your blood, your veins. It’s deep inside you. But you still feel insecure that you learnt the language in the home, you didn’t learn it in a thorough and formal way – for example, through a university course, through grammar, linguistics, literature.

Translators of colour who translate out of minoritised languages are often assumed to be a heritage speaker of that language. If they’re not, they face a constant demand to explain themselves. In fact, if you’re a translator who looks like you or someone in your family could have been born off the island, as it were, whatever language(s) you translate from, you’re constantly called upon to explain yourself: have you considered translating from your heritage language? Or, so you’re translating from the language of your childhood? (Unsaid: so you haven’t studied it like real literary translators do.)

I am treated like an exotic creature when people see that I am brown and fluent in French. The questions and comments I get asked in return are insulting and thinly conceal a wonderment that, as a person of colour, I had access to learning a foreign language at all.

The reality is that many translators of colour do not have a ‘heritage language’, or may be estranged from it as a result of colonial legacies, conflict, or assimilation pressures. Our mother’s tongue may be different to our father’s and it’s possible we know neither. Yet we are expected to, because ‘heritage’ is code for non-European, and functions as a perpetual reminder that we don’t belong.

I have been asked why I don’t study Black languages, as though that category means anything of substance. Black people exist all over the world. We come from several languages, and have had several languages forced upon us. What language is not a Black language, at this point?

The field is often described as too white, lacking diversity, not representative of the communities surrounding it.4 A common response is to call for ‘more diversity’ and lament that translators of colour are ‘hard to find’. Attention is then immediately turned to short-term solutions, such as creating pathways to train and mentor new translators to come into the industry. Without considering how those new translators would find a place for themselves in the field as it is.

After a translation reading, an established translator approached me to say he noticed my accent and wanted to advise me to get a co-translator who is a native speaker of English.

Diversity calls are problematic in a number of ways.5 They lump us all into two groups: white and ‘non-white’, homogenising ‘the diverse’ into a box that can be ticked by inviting one person of a non-white hue to a panel and calling it diverse. By talking about ‘diversity’ as the divergence from the norm, existing translators of colour are erased, engaged with as group representatives, not individuals. Newcomers are othered before they have even entered the room.

I can always tell when I’m only in a room as the diversity garnish because someone realised at the last minute that their guest list was all white.

Numbers are an easy distraction; the number of languages on a prize list (the further from Europe they sound like they are, the better), the number of people of colour on a panel or committee—both are seen to accomplish ‘diversity’ and signal ‘progress’.6 But these numbers don’t equate to making space for minoritised translators, writers, styles, languages, and Englishes, in all the different ways these may deviate from what is considered the norm. What these ‘diversity’ efforts do is create an illusion of inclusivity that in reality consists of a few, small spaces for us to squeeze into, shape ourselves by, shiny ourselves for. Power hierarchies prevail. Existing structures are kept intact.

Earlier this year, a colleague of mine remarked that I was the first Black translator he had ever met. I can’t help but wonder whether this is by design. Communities, networks, entire industries are structured in such a way that isolates a segment of us and makes us feel that we have to navigate all this alone.

‘Promoting diversity’, ‘celebrating multilingualism’, ‘nurturing minority talent’, ‘championing international voices’ are all things that can be done without acknowledging or challenging underlying structures.7 Without facing how the practice of translation itself centers whiteness and westernness, and how it defaults to reflecting and replicating colonial patterns. English is a colonial language. The work of anglophone translators—venturing out and bringing back, only understanding others by making them in their image—follows the routes of colonial acquisition. English is also a global language. The literatures written in English often grapple with its imperial legacies. Why can’t literary translation do the same? How can translators work with this larger-than-life language without acknowledging all the violence it may carry?

To untrained ears, English was the only language spoken in my family growing up. But underneath the violently enforced ‘standard’ English I think of as a veneer, our true language was African American Vernacular English, a variation on the English that was brutalized into my bloodline in the place of anything I would have been able to call a mother tongue. AAVE repurposes imperial English and ruptures its constraints. It’s dynamic. It’s warm. It’s evocative. It is the closest thing I have to something I can call my language.

Colonial acquisition has its rules and conventions.8 What is brought over is made to fit into the predetermined spaces of labs, libraries and museums, its difference accentuated but its foreignness contained. These rules and conventions have been internalised by many in the West who are allowed to go through life with uncontested identities. Their curiosity about what lies beyond the realms of their own identities remains trapped within a scale of otherness: too foreign on one end, not foreign enough on the other. We see this in the exoticising sparkle around ‘discovering’ literature from places that have little representation in the anglophone literary sphere, as long as they contain the expected degree of foreignness; no more, no less.

The agent said, ‘give me a story more typically Indian, you know. Caste. Women’s stuff. Poverty.’

For many anglophone publishers, stories from the Global South have to fit certain narratives and writing styles.9 Often ‘fluency’ is the main criterion used to assess the quality of a translation. Concepts of fluency shift our focus to the target language and the norms of its most standard form, the one with the highest capital: ‘This is what works in English’. Whose English?Ethical concerns are seen to stand in opposition to formal elements, rather than pathways to new forms of experimentation: ‘That would sound odd in English’. What if that which sounds odd to one person evokes familiarity for another?

While I pride myself on reading widely across different languages, I had never realised how much of what I was choosing to read in those languages was restricted by what had already been translated and ‘accepted’ by the West.

Migrating across linguistic and cultural borders means the translated text faces the same challenges as the migrant person in a new land: lack of belonging, pressure to assimilate, threats of erasure.10 It depends on where the text is migrating from. Some may find it easier to enter, easier to blend in. Other texts are held at the border and forced to prove their worth.

An agent I was working with told me there was a publisher interested in acquiring a book I’d translated a sample of, but that they refused to work with me because I was not a native speaker. Another publisher praised the same sample for how fluent it was, especially considering ‘she’s not a native speaker’.

The anglophone literary translation border force are the gatekeepers of the industry, deciding which texts, which translators make it through.11 They define the scope of a ‘good’ text, what will ‘work’ in translation, what will sell, whose English. They define the reader. They interrogate the text at the border. And as translators, we are often made to choose between internalising the gatekeepers’ terms and conditions and sending the text ‘back home’.

I’ve been an immigrant my whole life, and I will often find myself listing reasons why I belong in this country as much as the next person. I go through the same mental process with literary translation. I tell myself I have to be better than or I won’t be allowed to stay, in the same way as immigrants are made to feel they have to be exceptional, either in terms of their skills or their suffering—otherwise, what are they doing here anyway?

The consequences of having a homogenous group at the port of entry is that a dominant, mainstream perspective is centred, actively encouraged, protected.12 Anxiety about the ‘foreign’, the ‘different’, is packaged as economic viability. These stories and the characters in them are seen as ‘unrelatable’, without spelling out exactly to whom.

I’m self-conscious of how much I have to prove myself, as an outsider in a Eurocentric field. What kinds of risks am I not taking or choices am I not making as a translator for the sake of proving my ‘normalcy’?

The assumed readers that publishers cater for are undemanding and risk averse. These are readers who want things to make sense, instead of wanting to make sense of things, who want to journey into another world that is identical to the one they have already imagined. Demands are made on behalf of these ‘core readers’ with little interrogation of the underlying assumptions about who they are and who else is being excluded as a result. There will always be a ‘for whom’ question. The only ethical choice, then, is to be conscious of the question and to respond to it with intent.

I can’t imagine that many of the white translators I know feel the same debt to the source language, the same desire to do it justice. Because that indebtedness comes, I think, from my own experiences of having my English(es) mocked, disparaged, invaded, misappropriated, co-opted, used for personal gain, and stamped out. I do not want to reenact that violence on another language.

When translation is done well, daringly, it can broaden perspectives, shift paradigms, challenge assumptions. But it doesn’t carry inherent value in its own right. An ethical approach to translation requires understanding enough about linguistic power hierarchies to take chances on destabilising dominant forms of English, to deny those forms the unquestioned privilege of making the whole world in their image.

I am fascinated by the ability of translation to inform, add to, and expand the target language. In my translation practice, I try to work towards ways of translating that push against the Western gaze and decolonize translation practices.

Because power breeds entitlement, unquestioningly accepting and benefiting from the supremacy of a standardised English leads to the belief that anything can, and should, be translated.13 Untranslatability is not a temporary barrier to be broken into but a fundamental right. Understanding this is the cornerstone of translation as a reflective practice that involves ongoing learning and humility.

The tendency to view ‘otherness’ as a challenge or a threat, to be neutralised with ‘fluent’ translation, rests on the many assumptions about who translates literature and for whom, and enables those assumptions to seep into every aspect of the translation experience.18 A more ‘diverse’ translation cadre will not seamlessly lead to a more diverse translation practice. Not while translators are measured by their ability to fall in line with a fluency imperative that implicitly privileges the dominant language and pits ethics against creativity as opposing forces. Only by continuing to shine the light on the power dynamics inherent in the ways we translate and the ways we talk about translation—until questioning the norms of the practice becomes the norm—will the private, complex, layered subjectivities of translators find spaces to flourish.

POSTSCRIPT

Writing this piece has been tremendously difficult. Somewhat surprising given that when we – the co-authors – first met, it was precisely over the themes of this essay that we bonded. But back then it was our secret conversation. We enjoyed the uncomplicated relief of being able to discuss things we didn’t discuss with many others. Then the questions we were asking ourselves became public ones. And the answers that were being thrown around them seemed hasty and incomplete. A deeper engagement is needed – we know that much. We were never quite sure if it was as much about literary translation as it was about our place in the professional worlds we chose.

When we reached out to colleagues to share their experiences, we were struck by their generosity, honesty and willingness to trust two (in some cases) strangers with their personal stories. We realised that similar conversations were happening at the same time as ours, focussed on different themes in different but related ways. And it is precisely those conversations that we want to keep going.

For sharing their experiences (via the interspersed quotes, and in many more not included in the final version), our sincerest thank you to Aaron Robertson, Anton Hur, Bruna Dantas Lobato, Edwige-Renée Dro, Jen Wei Ting, Jeremy Tiang, Julia Sanches, Kavita Bhanot, Kavitha Karuum, Khairani Barokka, Kólá Túbòsún, Naima Rashid, Paige Aniyah Morris, Somrita Urni Ganguly, and Yilin Wang.

Endnotes

[

←1

]

Read Jeremy Tiang’s piece ‘The world is not enough’.

[

←2

]

Data published by Nielsen Book highlights a Eurocentric focus in terms of translators’ source languages in the UK.

[

←3

]

A 2020 Higher Education Policy Institute report defines ‘heritage languages’ as ‘those spoken by a minority community, often learned at home or in Saturday schools’.

[

←4

]

A 2017 Authors Guild survey in the US compiled data from 205 literary translators and found: → 83% of translatorswerewhite,6.5% Hispanic or Latinx, 1.5% Black/African American, 1.5% Asian American and 1% Native American. → ‘the most common languages were French, Spanish, German, and Italian, followed by Portuguese, Russian, Chinese, Catalan, and Japanese.’

[

←5

]

The 2019 UK Publishers Association Workforce Survey, based on data from over 57 publishing houses and 12,700 employees, found:→ 86% of respondents identified as white → 90% straight → 69% female → 93% non-disabled; → a ‘significant lack of class diversity: 20% of respondents had attended a fee-paying school (3 times the UK average)’

[

←6

]

For the 2020 Warwick Prize for Women in Translation there were 132 titles entered for the prize in 34 languages, which, as stated on the website, was a ‘substantial increase’ from the last three years. Of the 132 titles, there were: → 99 titles from Europe→ 29 titles from Asia and Africa combined → 5 titles of the 132 were written by Black women→ 11 of the 111 translators are translators of colour On the 2021 International Booker Longlist, the only translator of colour was Chen Zeping, who appears as co-translator.

[

←7

]

Read Kavita Bhanot, “Decolonise, not Diversify” and Brian Friel’s Translations.

[

←8

]

Read Kaiama L. Glover’s ‘“Blackness” in French: On Translation, Haiti and the Matter of Race’.

[

←9

]

During the Publishing Panel at the 2020 British Centre for Literary Translation Summer School, one publisher described how their process started with checking the translation has ‘got the kind of fluency we would be looking for’.

[

←10

]

Read Madhu Kaza’s Editor’s Note to Kitchen Table Translation.

[

←11

]

The 2015 Writing the Future report highlighted that a Black,Asian or minority ethnic writer’s ‘best chance of publication’ was to write on themes such as ‘racism, colonialism or post- colonialism, as if these were the primary concerns of all BAME people’.

[

←12

]

According to a 2020 Spread The Word report,‘the idea of the core reader as a white, middle-class older woman (sardonically referred to as “Susan” by several of [the report’s] respondents) remains dominant [and] while publishers would like to publish more writers of colour, they believe it is too commercially risky to do so.’

[

←13

]

Read Édouard Glissant on the ‘right to opacity’ and Khairani Barokka’s ‘Translation of/as Absence, Sanctuary,Weapon’.

[

←14

]

In an interview with Veronica Esposito, Yasmine Seale responds to a question about her background with this creative ideal: ‘Where I am from and where I live may be less important here than the more private, complex biographies of eye and ear’.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

‘2017 Authors Guild Survey of Literary Translators’ Working Conditions: A Summary’, report published by The Authors Guild, 2017: www.authorsguild.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/2017-Authors-Guild-Survey-of-Literary-Translators-Working-Conditions.pdf

Porter Anderson, ‘Nielsen Reports Translated Literature in the UK Grew 5.5 Percent in 2018’, Publishing Perspectives, 2019: publishingperspectives.com/2019/03/nielsen-reports-translated-literature-in-uk-grows-5-percent-in-2018-booker

Porter Anderson, ‘The UK’s International Booker Prize 2020: The Longlist is Announced’, Publishing Perspectives, 2020: publishingperspectives.com/2020/02/international-booker-prize-2020-longlist-is-announced

Khairani Barokka, ‘Translation of/as Absence, Sanctuary, Weapon’, The Poetry Review, 108:2, 2018: poetrysociety.org.uk/translation-of-as-absence

Kavita Bhanot, ‘Decolonise, not Diversify’, Media Diversified, 2015: mediadiversified.org/2015/12/30/is-diversity-is-only-for-white-people

Megan Bowler, ‘A Languages Crisis?’, report published by the Higher Education Policy Institute, 2020: www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/HEPI_A-Languages-Crisis_Report-123-FINAL.pdf

‘Diversity Survey of the Publishing Workforce 2019’, report published by The Publishers Association, 2019: www.publishers.org.uk/publications/diversity-survey-of-the-publishing-workforce-2019

Veronica Esposito, ‘”Wild Irreverence”: A conversation about Arabic Translation with Yasmine Seale’, World Literature Today, 2020: www.worldliteraturetoday.org/blog/interviews/wild-irreverence-conversation-about-arabic-translation-yasmine-seale-veronica

Édouard Glissant, ‘For Opacity’, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1997: www.jackie-inhalt.net/reh/bilder/edouard-glissant-for-opacity.pdf

Kaiama L. Glover, ‘”Blackness” in French: On Translation, Haiti, and the Matter of Race’, L’Esprit Créateur, John Hopkins University Press, 59:2, 2019: muse.jhu.edu/article/728220

Madhu Kaza, ‘Editor’s Note’, Kitchen Table Translation: An Aster(ix) Anthology, Blue Sketch Press, 2017.

Audre Lorde, ‘Poetry Is Not a Luxury’, Sister Outsider, Penguin Books, 2019.

‘Publishers Panel’, British Centre for Literary Translation, Summer School, 2020: www.youtube.com/watch?v=aHCmWtb8jyU

‘Re:Thinking “Diversity” in Publishing’, report published by Spread The Word, 2020: www.spreadtheword.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Rethinking_diversity_in-publishing_WEB.pdf

Jeremy Tiang, ‘The World is Not Enough’, Asymptote: www.asymptotejournal.com/special-feature/jeremy-tiang-the-world-is-not-enough

Olga Tocarczuk, Flights, trans. Jennifer Croft, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2017.

The Warwick Prize for Women in Translation, list of eligible titles, 2020: warwick.ac.uk/fac/cross_fac/womenintranslation/hp-contents/warwick_prize_for_women_in_translation_2020_-_eligible_submissions_.pdf

‘Writing the Future Report: Black and Asian Authors Publishers in the Market Place’, report published by Spread The Word, 2015: www.spreadtheword.org.uk/writing-the-future

2. “BLACKNESS” IN FRENCH: ON TRANSLATION, HAITI, AND THE MATTER OF RACE

Kaiama L. Glover

The basic grammar of blackness is often […] lost in translation.

—Brent Edwards, The Practice of Diaspora1

In this article, I reflect on the stakes and the practice of translating into English an Afro-diasporic text written in French. More specifically, I address the imbricated layers of translation involved in bringing renowned Haitian author René Depestre’s prize-winning 1988 novel Hadriana dans tous mes rêves first to the space of metropolitan France and, subsequently, to an anglophone reading public. Reflecting on the translation of this particular work provides an opportunity to consider the various challenges that inhere in translating Haiti, both metaphorically/ culturally and literally/linguistically, to a world largely primed for its degradation.2 A close look at Hadriana compels us to examine the stakes of translating, in particular, to a global readership that most often views Haiti through the lens of irrevocable, demeaningly racialized difference. What is entailed in ‘carrying over’3 meaning from a Haitian context to a non-Haitian, Euro-francophone audience and, from there, to an Afro-anglophone world? What is the task of the translator within this racially hierarchized transatlantic space?

In thinking through these questions, I have taken as my point of departure writer and translator John Keene’s call for more substantive reflection on race across diverse cultural frameworks. Keene argues that to translate ‘blackness’ in its various iterations and geo-cultural contexts might serve to make plain the contingency of race as lived experience and, further, to push against homogenizing, U.S.-centric conceptions of what blackness represents. “Were more black voices translated,” posits Keene, “we would have a clearer sense of the connections and commonalities, as well as the differences across the African Diaspora, and better understand an array of regional, national, and hemispheric issues.”18 Indeed, while there exists great continuity among the many sites of Africa and its diasporas, there is no such thing as a global ‘Black experience.’ Diverse and divergent colonial and postcolonial histories have produced heterogeneous Black geographies, epistemologies, cultures, and languages, rendering Black peoples in many ways illegible to one another.

It is within this broad context that I consider the geo-cultural site-symbol that is Haiti, a place whose ‘blackness’ continues to be seen as uniquely pathological. It must be said: Haiti is ‘Black’ in a special kind of way. Although as foundationally Afro-diasporic as its Caribbean neighbors, Haiti has been long disparaged by the particular racialized denigration of its popular religion. The idiosyncrasy of Haiti’s ‘blackness’ has everything to do with degrading perceptions and representations of Vodou. A clear case of what Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot identifies as the deployment of culture to euphemize the idea of race, North Atlantic discourse concerning Haiti consistently casts the island nation as fundamentally stunted by its Afro-spiritual practices. Insofar as theories of cultural difference equate more and less transparently with theories of race, the stigmatization of Vodou as cultural practice is unequivocally racial.

Haiti thus presents a high-stakes example of ‘blackness’ in need of translation. But not just any kind. Haiti needs translation as a potential tool/site of articulation, that is, as “a process of linking or connecting across gaps” (Edwards 11), of facilitating “the recognition of necessary heterogeneity and diversity,” so as to produce “a conception of ‘identity’ which lives with and through, not despite, difference.”5 Translating Hadriana was, for me, such a potential “discourse of diaspora” (Edwards 12), a destigmatizing effort that might place an alternative narrative of Haitian Vodou into circulation in the Global North. Following Keene, I have understood translating Haitian literature from French into English as a means, however modest, of creating space for an expanded notion of blackness within the African diaspora.

Haiti’s persistent denigration in globally circulating narratives of perceived political dysfunction and socio-economic despair makes this task of translating the “Black Republic” very much a matter of ethics. As Tejaswini Niranjana has argued convincingly, “[i]n a postcolonial context the problematic of translation becomes a significant site for raising questions of representation, power, and historicity.”6 In order to grasp fully the significance of this claim, it is important to begin by thinking about the means via which writers from the so-called Global South present themselves for circulation outside of their local context, presenting their ‘foreignness’ for appreciation and, ultimately, consumption on familiar terms.

Vodou and Haiti in a global frame

What is a book anyway? It is a product, a commercial item. I write in order to be read, in order to sell to the people around me. But if they cannot read, my book is worth nothing. It is a commercial product which is going to stay here, insulted by dust.7

—René Philoctète

In 1946, nineteen-year-old Haitian poet and student revolutionary René Depestre left his homeland in the wake of a national political transformation he had been instrumental in effecting. Depestre spent the subsequent thirty years of his life engaged in militant socialist activism throughout Western and Eastern Europe, South America, and the Caribbean, including twenty years in Cold War Cuba, all the while prolifically writing poetry and political essays. He currently resides in Lézignan-Corbières, in the Aude region of southern France. Throughout these lifelong peregrinations, Depestre has sought to reach an audience situated well beyond the space of his native land. Be it in his capacity as poet, novelist, or political essayist, he has written consistently for a public situated primarily outside of Haiti, presenting his island to another—an Other—global space. In this respect, Depestre has long been preoccupied with the power differential that places him on the margins of a world order he has worked passionately to upset. He has understood that staging his desired intervention requires a sustained practice of cultural translation.

Depestre’s extra-insular aspirations are as readily apparent in his poetry and prose fiction as they are in his political writings, and Hadriana is no exception. Steeped in the so-called marvelous real, Hadriana dans tous mes rêves foregrounds the fantastical and the erotic within a frame that opens onto the Atlantic world from a decidedly Haitian perspective. Upon its publication, Hadriana sold almost 200,000 copies and won several awards, including the prestigious Prix Renaudot.8 But as Colin Dayan has brought to light, the popular success of the novel in many ways reflected and revealed the racialized projections and exoticist desires of the French reading public. Reviewers in France encouraged readers to “let themselves go,” to immerse themselves in “the land of zombies,” and to embrace the “deflowerings, aphrodisiac emanations, sexual exploits, forbidden ecstasies” and “irresistible sorcery” of the Haitian folk.9

Despite—or, perhaps, given—the terms of the novel’s acclaim in France, Hadriana has been the subject of sustained critique in academic circles. Where French reviewers and award-givers rejoiced in the escapist fantasies permitted by Depestre’s tropical narrative, North Atlantic Caribbeanist scholars have accused the author of exploiting Haitian culture as an exotic commodity for European consumption.10 Although it is certainly true that many postcolonial writers choose or are compelled to live in the Global North while continuing to write about their home countries, the fact that Depestre distanced himself from socialism as of the late 1970s and ultimately retired to the French countryside has left him particularly vulnerable to critical interrogation involving questions of authenticity and political engagement.

It is the case that Hadriana dans tous mes rêves tells a Haitian story to a non-Haitian audience; the novel is marked linguistically, structurally, and narratively by efforts to translate Haiti (in)to a wider francophone space. Published in France by the prestigious Éditions Gallimard, Hadriana necessarily belongs to the fraught category of “world literature,” a network of literary works that is ultimately embedded within the canons and hierarchies created by European imperial nation-states. Explicit elements of the novel make plain Depestre’s attentiveness, at least in part, to a non-Haitian readership. Take, for instance, the extensive “Glossaire des termes haïtiens (Langue créole)” placed as an appendix to the narrative. Although the vast majority of the glossed words in this addendum relate to Vodou and so belong to a Haitian Creole lexicon, Depestre has rendered them orthographically in French. Also worth noting is Depestre’s strategic deployment of epigraphs throughout the novel. His opening citation presents lines from a poem by French Surrealist René Char and is followed immediately by an allusion to French Surrealist intellectual André Breton’s 1937 novel L’amour fou. Subsequent sections and chapters of Hadriana are framed by the words of James Joyce, Kateb Yacine, Victor Hugo, Johann Wolfgang von Gœthe, and Sophocles. Depestre makes use of these epigraphs to situate his novel, subtly yet insistently, within a predominantly European canon. He is clearly concerned both with Hadriana’s linguistic legibility and with the novel’s positioning vis-à-vis the “regimes of value”11 that consecrate the literary on a global scale.

This is the context within which Depestre has been subject to disapproval—critiqued for his perceived consent to, if not collusion with, the racist and ethnocentric “fetishisation of cultural otherness” (Huggan 10) mobilized by former and current imperial centers of the North Atlantic to circumscribe and exploit the Global South. It is a critical response that is bound up in anxieties regarding what theorist Graham Huggan has labeled “the postcolonial exotic.” Huggan’s concept outlines the recuperative tendencies of the Western literary institution—its capacity to absorb and domesticate difference as it consumes it. Indeed, postcolonial writers are often called upon to translate their foreignness for institutions, industries, and consumers situated primarily in the North Atlantic. Doing so is a tricky enterprise. Independent of an author’s purpose or desire, a text can be easily co-opted “as an exotic good, not so different in its packaging from all of the other colonial exotica making its way into the metropole.”12 Postcolonial writers thus are caught within something of a bind. How does one represent Global South culture without sensationalizing it, reifying existing racial stereotypes, or censoring its idiosyncrasies in the interest of rendering it more palatable to a world that denies its value(s)? How does one present non-Western culture to the West for consumption (comprehension, consideration) without betraying that culture in the process?

There is a fine line, it is true, between opening a window onto an “Other(ed)” culture and “staging racial and ethnic stereotypes” for commercial gain (Watts 11). This is arguably the line Depestre walks in Hadriana dans tous mes rêves. In chronicling the adventures of a pretty French girl who gets turned into a zombie, Depestre admittedly does not shy away from representing the pathologies of Haitian Vodou. He incorporates the unsavory dimensions of Haiti’s religious practices, and he invites an interrogation of Vodou’s ambivalence with regard to matters of race and gender. By including such over-the-top elements as evil sorcerers, sex-crazed human butterfly hybrids, and, yes, zombies, he risks affirming Western stereotypes about Afro-diasporic religion. By the same token, however, Depestre takes care to portray the intricacies of Vodou as epistemology, aesthetic, and faith.

At about the midpoint of the novel, for example, Depestre’s narrator-protagonist Patrick Altamont (a character whose biography maps almost perfectly onto Depestre’s own) presents a veritable anthropological treatise on the zombie myth in Haitian and global history. Titled “Prolegomena to a Dead-End Essay,” the long passage lays out nine “propositions” that address the intersections between North Atlantic racism, global capitalism, and the philosophical purchase of Haitian cultural expression. Here and elsewhere in the novel,13 Depestre’s overtly outward-facing authorial gestures demand that Haitian Vodou be taken seriously as knowledge-system and worldview.14 His narrator’s thoughtful meditations on the mechanisms and philosophies of Haitian spirituality counterbalance and contextualize the more titillating portrayals of Vodou in the novel. The passages in which he explicates the intricacies of the zombie’s juridical and legislative embeddedness in Haitian society, for example, or his staging of Vodou and Catholic rituals as equally valid and valued in the Jacmelian community, establish Vodou’s complexity and real social legitimacy. Moreover, just as Depestre unabashedly represents Vodou’s erotic investments, its preoccupation with blood and death, its hyper-valuation of whiteness, and its misogynist tendencies, he also gives us its practices of healing, its nourishment of the communal, and its insistence on joy and possibility.15 To his reader, then, the responsibility for recognizing that a similarly fundamental duality informs the teachings and practices of every one of this world’s most sanctioned global faiths.

Packaging Hadriana: the tasks of the translator

The dynamics of translation in a Caribbean frame must be inscribed within the region’s histories and their afterlives; and these dynamics tend to suggest inequality and friction more than any senses of free flow and equivalence.

—Charles Forsdick, “Translation in the Caribbean, the Caribbean in Translation”16

If Depestre’s novel offered a translation of Afro-Haitian culture to a non-Haitian, francophone audience in the late 1980s, leaning as it did right into the whirl of complexities surrounding the global image of Haitian Vodou, my translation of Hadriana proposed carrying both Haiti’s culture and language(s) across to a new target–reading public thirty years later. As an African-American woman of Caribbean descent, I kept foremost in mind three specific engagements in realizing this task: first, translating responsibly within the maelstrom of existing narratives about Haiti and ‘blackness’/Vodou; second, translating to and for a desired Afro-diasporic readership; and third, remaining attentive to the ‘packaging’ of my translation.

The translator of Haitian literature must keep in mind “the politics of translating and the ethnocentric violence that sometimes accompanies it.”17 If done successfully, translating the work of postcolonial Black writers reveals “the range and complexity of black lives” on a global scale (Keene). If not, there can be more and less direct consequences regarding global policies toward peoples in ‘Black’ nations. Failures of cultural translation create hierarchies of value wherein ‘lesser’ cultures are mis-read as lacking or deficient—and subsequently are deemed worthy or not of protection from harm. As Huggan has convincingly noted, insofar as translation functions within a global market that tends to commodify difference, “the exoticist production of otherness […] may serve conflicting ideological interests, providing the rationale for projects of rapprochement and reconciliation, but legitimizing just as easily the need for plunder and violent conquest” (Huggan 13). The case of Haiti provides a stark instance of the ways in which translation informs the discourses that determine which Black lives matter and, relatedly, the success or failure of policies and practices that have an explicit impact on those lives.

The power differential between Haiti and those (putatively post-)imperialist nation-states of Europe and North America that have been so imbricated in Haiti’s social, political, and artistic institutions makes the question of translation less one of “the unequal power relations between languages” (Bassnett 343) and more one of the unequal power relations between cultures. Insofar as the majority of Haitian literature is translated into English from French, concern with the subjugation of a minority language is not ‘the problem.’ Rather, the concern is the subjugation of a racial and cultural “minority position” (Bassnett 341). In this position, Haiti and Haitians are assumed to be at once excessively legible (as in, transparent and simplistically two-dimensional) and absolutely illegible (as in, incomprehensible and ‘other’). The most pernicious and obvious of these assumptions hinge on the matter of race. Exceptional and absolute, Haiti’s ‘blackness’—again, a ‘blackness’ fundamentally linked to Vodou—marks its every interaction with the world beyond its borders.

As postcolonialist cultural theorist Stuart Hall rightly argues, it is crucial not only to identify ways in which “economic structures are relevant to racial divisions,” but also to consider “how the two are theoretically connected.”18 The first task is to attend to “the specificity of those social formations which exhibit distinctive racial or ethnic characteristics,” what Hall names “this ‘something else’” that translates backward and forward between the social/racial and the economic (Hall, “Race” 20, emphasis mine). Vodou is an instance of “this ‘something else.’” It is an ostensibly “extra economic” (Hall, “Race” 20) factor that has a significant impact on Haiti’s legibility to the outside world—a cipher through which the nation’s political and economic struggles have been read, especially in the United States. As I have written about elsewhere, Vodou has been aggressively fashioned and thus widely perceived as an obstacle to Haiti’s development.19 Across various media and in myriad geocultural spaces, “no religion has been subject to more maligning and misinterpretation from outsiders over the past century.”20 From aid organizations, to the news media, to the Hollywood film industry, “the threatening spectacle of Vodou”—or “voodoo,” in its so-called U.S.-American “translation”—is consistently deployed “by outsiders to signal the backwardness and indolence that they feel best describe Haitian history.”21