7,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Antelope Hill Publishing LLC

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

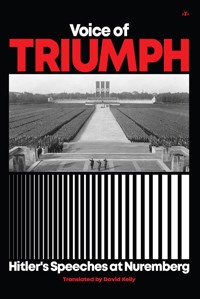

Nuremberg has served for centuries as a hub of political life in Germany. In the day of the Holy Roman Empire, Nuremberg boasted the high status of a Free Imperial City and hosted several important Imperial Diets, or Reichstage. The National Socialists framed themselves and their new Germany as the inheritors and successors of Germany’s rich political and cultural history stretching back to this first Empire, in which Nuremberg’s magnificent medieval old town stood out as an important symbol.

Today, the city’s name is for many almost synonymous with the NSDAP’s annual rallies held there from 1933 to 1938, immortalized in the iconic cinematography of Leni Riefenstahl’s Tr

iumph of the Will. The mere mention of it conjures images of red banners raised to the sky, and endless ranks of brown-shirted stormtroopers standing at attention.

Of course, no picture of National Socialist Germany would be complete without the presence of Adolf Hitler, who as a historical personage looms large over the entirety of the twentieth century. At the Party Congresses in Nuremberg, Hitler’s renowned skill at public speaking and the almost mystical gravitas he commanded stood front and center. These speeches provided an important setting from which he extolled on the Party’s goals and accomplishments for the new year, as the National Socialist revolution rapidly transformed Germany from a battered and exhausted nation into an ambitious rising power in world affairs.

It is with great honor that Antelope Hill Publishing presents

Voice of Triumph: Hitler’s Speeches at Nuremberg, in new translations from the original German. Within the pages of this book is a quintessential chapter of history from the most influential politician of the twentieth century, according to friend and foe alike.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Voice of Triumph:

Hitler's Speeches at Nuremberg

1933, 1935–1938

Voice of

TRIUMPH

Hitler’s Speeches at Nuremberg

Translated by David Kelly

A N T E L O P E H I L L P U B L I S H I N G

Translation Copyright © 2024 Antelope Hill Publishing

Voice of Triumph: Hitler’s Speeches at Nuremberg is a translationfrom the original German transcripts of Hitler’s speeches.

Note: Unfortunately, our research found that the 1934 Party Congress speeches have been lost to time, with exception of the excerpts that are shown in the film Triumph of the Will. As such, the current edition lacks these speeches. If you have possession of them, please contact Antelope Hill Publishing and we will ensure that they make it into the second edition of this work.

First Antelope Hill edition, third printing 2024.

Translated by David Kelly, 2024.

Cover art by Swifty.

Edited by Harlan Wallace.

Proofread by Tom Simpson.

Layout by Sebastian Durant.

Antelope Hill Publishing | antelopehillpublishing.com

Hardcover ISBN-13: 979-8-89252-014-0

Paperback ISBN-13: 979-8-89252-013-3

EPUB ISBN-13:979-8-89252-015-7

CONTENTS

The Führer’s Speeches at the 1933 Party Congress of Victory

The Course of the NSDAP’s Fifth Party Congress

The Proclamation of the Führer at the Opening of the 1933 PartyCongress

The Führer’s Speech at the Cultural Conference

The Führer’s Cocluding Remarks at the 1933 Party Congress

The Führer’s Speeches at the 1935 Party Congress of Freedom

The Course of the NSDAP’s Seventh Party Congress

Reception of the Führer in the City of Nuremberg

The Proclamation of the Führer at the Opening of the 1935 PartyCongress

The Führer’s Speech at the Groundbreaking of Congress Hall

The Führer’s Speech at the Cultural Conference

The Führer to the Workmen

The Führer Before the German Expatriates

The Führer to the Political Leaders

At the Celebration of the Hitler Youth

At the Roll Call of the Brown Army

The Führer’s Speech at the Notable Reichstag Session in Nuremberg

To the Soldiers of the Armed Forces

The Führer’s Concluding Remarks at the 1935 Party Congress

The Führer’s Speeches at the 1936 Party Congress of Honor

The Course of the NSDAP’s Eighth Party Congress

Reception of the Führer in the City of Nuremberg

The Proclamation of the Führer at the Opening of the 1936 PartyCongress

The Führer’s Speech at the Cultural Conference

The Führer to the Workmen

The Führer Speaks to the National Socialist Women’s League

The Führer to the Political Leaders

At the Celebration of the Hitler Youth

The Führer Before the German Labor Front

At the Roll Call of the Brown Army

To the Soldiers of the Armed Forces

The Führer’s Concluding Remarks at the 1936 Party Congress

The Führer’s Speeches at the 1937 Party Congress of Labor

The Course of the NSDAP’s Ninth Party Congress

Reception of the Führer in the City of Nuremberg

The Proclamation of the Führer at the Opening of the 1937 PartyCongress

The Führer’s Speech at the Cultural Conference

The Führer to the Workmen

The Führer at the Groundbreaking of the German Stadium

The Führer to the Police

The Führer to the Political Leaders

At the Celebration of the Hitler Youth

The Führer Before the German Labor Front

At the Roll Call of the Brown Army

To the Soldiers of the Armed Forces

The Führer’s Concluding Remarks at the 1937 Party Congress

The Führer’s Speeches at the 1938 Party Congress of Greater Germany

The Course of the NSDAP’s Tenth Party Congress

Reception of the Führer in the City of Nuremberg

The Proclamation of the Führer at the Opening of the 1938 PartyCongress

The Führer’s Speech at the Cultural Conference

The Führer to the Workmen

The Führer to the Political Leaders

At the Celebration of the Hitler Youth

At the Roll Call of the Brown Army

To the Soldiers of the Armed Forces

The Führer’s Concluding Remarks at the 1938 Party Congress

THE FÜHRER’S SPEECHESAT THE 1933 PARTYCONGRESS OF VICTORY

THE COURSE OF THE NSDAP’SFIFTH PARTY CONGRESS

An introduction

Thirteen long, hard years the Brown Army fought. Thirteen years, in all the districts, cities, and villages all across Germany, workers, farmers and burghers, old frontline soldiers and the young volunteers of the second freedom fight hoisted the blood-red flag of the German revolution, wrestled and fought for every single new comrade, every fellow German, every woman who joined the ranks of National Socialism’s great community of destiny. Thirteen long years in which—like healthy cells in a sick body—fellowships of blood and ideas formed all over the German land, from which a new spirit flowed into a despondent and famished people; in which, despite being a time of bleakest decay, ideals became reality—ideals which loomed over the heads of a rotted ruling class like fiery beacons of a coming rebirth; in which there was devotion again and faith, in which there was purity and fellowship, in which lived a Führer and one holy duty: Germany.

The proud, bold breath of this fellowship of German revolution wafted into the Volk and into all corners of the German land. This breath took hold of those who were not yet hollowed out, but who were just tired from all the hopelessness and pressure of a dirty, dishonorable revolt and its dishonorable consequences. Suddenly they lifted their heads again, as from afar they could hear the defiant march step of the eternal Germany, as young fists took up a young flag bearing the ancient German symbol of victory and carried it through the slavering hatred of inferior humanity, all the while laughing and victorious, faithful and brave. They lifted their heads and became joyous and proud again, like those who marched—and then they marched with them. Anyone who was still healthy marched with them: the young and old factory workers marched along, who refuted Marxist slave morality with the honor of their work. The old and young farmers marched along, who with desperate doggedness wanted to defend their fields and birthright against foreclosure by bankers and capitalist interests. The burghers and their sons marched along, whose blood and hearts went out to their working comrades to build a new Germany. They all marched along. They numbered well over a hundred thousand and always kept growing—andtoday one Volk, one destiny, and one age marches behind the flag for which three hundred undefeated comrades fell. This flag is sanctified like no other piece of fabric by blood and selfless sacrifice; it is a flag for which a hundred thousand willingly and joyously took up hardship and misery. A Volk marches that has been called back home to itself by a man; a Volk that has found itself again through the enjoinders and calls, the struggles and action, of the Führer Adolf Hitler.

Bells called the National Socialist Party Congress into session. There was deep, stricken silence among the thousands of people who gathered in all parts of the city. The bells that tolled there were bells of thanksgiving, resounding over a nation saved from deep brokenness. They were bells of thanksgiving that told of the nation’s dire wrestling against almost certain downfall and despair. They were bells of a promise, bells of a people’s fidelity to its most beautiful tradition and noblest history.

And these bells resounded over a city in whose most distant corners and narrowest alleys the love and gratitude of the poorest and simplest often found their most touching expression. This city’s streets and houses disappeared behind the forest of garlands and flags. Here every window announced the joy with which the whole people began these festive days. Here storms of jubilation, gratitude, and devotion accompanied every step of the Führer. And yet, all this was but a small slice, a quiet utterance, for there were not merely a hundred thousand, but millions—a whole people that wanted to express its ultimate love and faith. Nuremberg was only one heartbeat in the new life of the awakened nation—but this one beat gave an inkling of the power that this one man’s call awakened.

Rudolf Hess, representative of the Führer, opened the great Party Congress with these words: “I hereby open the fifth Party Congress of the NSDAP, the first Party Congress after National Socialism’s seizure of power. I open the Party Congress of Victory.” As he did so, and as the standards of the SA were carried in amidst the din of a march and under the welcome of the entire leadership cohort of the New German Reich, the celebration became a hundred times greater than the welcoming cheers of the population. More than a celebration, it became a consecration, and the magnitude of this victory was revealed more clearly and beautifully than ever before.

How many dreams were dreamt in silent hours among the brown comradeship of a coming third and eternal Reich? But no one could imagine it. Yet now it was reality, through the ancient, indissoluble bond between leadership and discipleship, a reality that burst through the confines of one party and grew to encompass the whole state. This reality now linked the highest wielder of state power with the unknown comrade of the brown front. With reverence, the giant assembly of the first men of the New German Reich greeted the old victory symbols of the SA, carried to their triumph by the same trusty workers’ and farmers’ fists that hoisted them through all the years of terror and persecution. A deep gratitude flowed through the hall and acknowledged the three hundred comrades, whose spirits accompanied the standards of victory to their place of honor.

At the same time these thousands turned their eyes toward the man whose greatness of leadership alone made this triumph possible. This man we saw and heard in hundreds and thousands of gatherings, years ago in smoke-filled rooms, then in Germany’s largest halls, and finally in the final struggle for power. Every hour and with every word he fought and struggled for the sake of love and fellowship and the understanding of the whole German Volk. He never let the flag waver. He first appeared to us all in his full greatness in the hour when no one saw a path forward, when he himself was overstretched and overworked, and yet he always decided on the hardest path, for uncompromising struggle, for unmistakable and uncompromising fealty to the flag and the idea. He was ridiculed and scoffed at, hated and loved—but his word and his deed remained the same. His answer to every persecution and difficulty in those unspeakably difficult thirteen years was: “I believe in this Volk; I believe in Germany.” This belief was given life and form in the faith of countless brown fighters, in the laughing love of a half million members of the Hitler Youth—boys and girls. Finally, it manifested in the fealty of the whole people, which shone forth best in the sacrifice and work of every individual for the well-being of the whole and for the renewal of the state.

The faith of the best and even the loyalty of the least now hung over the Party Congress like a silent blessing, like a covenant in which the sacrifices of countless generations came alive again and lent their strength to the newly awakened will to life of the nation. It was as if a million voices from every village and every living room in Germany intoned along with Rudolf Hess when, in his opening remarks, he turned to the Führer and said: “My Führer! As leader of the party, you were our guarantor of victory. When others faltered, you remained steadfast. When others looked to strike a compromise, you were unbending. When others let their courage wane, you showed new courage. When others left our ranks, you gripped our flag more determinedly than ever, until the flag became the flag of the state, thus signaling our victory—and again, you carry the flag forward! As leader of the nation, you are our guarantor of ultimate victory. We greet the leader and in him we greet the leader of the nation. Adolf Hitler, we greet you!”

The Party Congresses of the NSDAP were always a balancing act. They were a balance between discipline and the will of the movement, which found its symbolic expression in the marches of the SA, SS, and Hitler Youth. Likewise, it was a balance of the intellectual work that had been done in the years leading up, and the shaping and ramifications of the intellectual content of the movement. One never experienced a stagnant moment or a step backward at the National Socialist Congresses. Indeed, as the brown columns visibly grew in determination, discipline, force, and unity, so each Party Congress became a milestone of increased intellectual power, where the intellectual agenda was broadened and deepened, and the future’s tasks became clear. The old parties of bourgeois Marxist liberalism were content to blather on about their ancient yet never realized program goals, but all could see that at the NSDAP’s Party Congresses the worldview of National Socialism formed through the combined efforts of the men who heeded the Führer’s calls for collaboration in the Congresses.

At the Party Congress of the NSDAP the crystal-clear summit of the idea grows, as it were, out of the march of the brown columns. Here the feel and rhythm that animates the march of the SA, SS, and Hitler Youth obtains its ultimate intellectual, self-conscious purpose. At the National Socialist Congress, idea and power, purpose and will merge into an indissoluble, inevitable creative entity.

In the early years this entity was the core of both the intellectual and disciplinary resistance of a young Germany against the old system. Even then the festivities of the NSDAP were the strongest concentration of energy and political insight; however, then they were of necessity oriented against the state, which clueless partisans had turned into an instrument of despotism that threatened the life and future of the people. With Adolf Hitler’s chancellorship, the great transformation of this center of resistance into the focal point of the new state will have occurred, as it was also in opposition, but now freed from all bonds and inhibitions. Thus began the interpenetration and cross-pollination of the state and the movement. However, the NSDAP remains what it was and should continue to be: the strongest expression of the nation’s will to live; the eternal, continually renewed powerhouse that animates the new German state.

Thus, the Party Congress of 1933 became the noble celebration of the brown fighters’ victory, as well as the most beautiful, liveliest expression of the German will for resurrection. It became the wellspring from which a new impulse proceeded into the whole national life—an impulse evident as much in the steady strength of the brown battalion’s march as in the grave seriousness of the great Congress.

The discipline of the SA has in the last months become the leading principle of the whole people, and yet the unanimous force of the 120,000 brown shirts in Nuremberg challenges every individual to ever higher subordination and stronger commitment. In the speeches of the National Socialist Congress, we saw the exclusive way and will of the new state. With overwhelming force, we saw how today National Socialism is beginning to transform every area of the state and is giving each organ of the state its new tasks and goals.

Today, the party and movement belong to the state. They will only keep legitimacy so long as they use this power for the common good of the nation. In truth, as the NSDAP represents the most incomparable organization of the most unconditional devotion to the state, so it must also preserve its identity as constant critic, as eternal troubled conscience, which holds up in the face of every accomplishment an image of an even higher challenge, to every sacrifice the example of an even greater selflessness in service of the whole. In this sense, the fighting community of the NSDAP will be eternal, and its fighters will build the new German order, whose one law will be the undying spirit of the eternal German volunteer soldier.

The proud blessing of this volunteerism—this also ruled the festival days of Nuremberg. This was happily self-evident for all, as the hundreds and thousands of fighters, called by the Führer to take their place in the state, gathered at the Party Congress as the great army of National Socialism, and in place of the hierarchy of the state there was the leadership hierarchy of the movement. Men who may have been ministers and high officials in the state were again mere party officials here and took their place among the rank and file of the fighting community. But in the place of honor here were the men who were first in the meritocracy of the party, and who were the most accomplished fighters and therefore the foremost men of the state.

Out of this lively combination of state and party grew an agenda for the coming years. National Socialism spent these days solicitously, drawing another hundred thousand German-blooded and German-spirited people, with its mysterious strength and greatness, inspiring them to work with us. It spent these days effectively, remaking itself, fulfilling itself, giving strength to its spiritual breadth and depth. Similarly, it will have one day solicitously and effectively taken hold of the whole Volk, with National Socialism changing its form and mass, but always remaining what it was upon its foundation: the mission, the project, the formation, the ever-recurring rebirth of the eternal Germany.

This German rebirth found its tremendous expression in the Führer’s six speeches. There was no one who, under the sheer force of these ideas, was not shaken by the dynamism of the National Socialist revolution and the creative power of its leader, who, even in victory, calmly and single-mindedly showed the way forward for the universally advancing new will of the nation.

The Führer’s great proclamation at the start of the Congress lays forth several eternal laws and traditional truths for all to see and consider. The observation of these laws and truths is what made the NSDAP’s rise and victory possible. It is a duty of the party to ensure that these laws will be observed in the future German state. The party will reach its goal through the elite, selected from among the people, as the Führer described them:

Among our tasks for the future is to craft a union between feeling and reason again, that is, to raise that untainted generation that will recognize the eternal lawfulness of development with a clear mind, and with this will deliberately find its way back to primitive instinct.

These words had to convince the nation that National Socialism’s revolutionary will for the formation of a new undeformed man, a new normal generation, would never rest on the laurels of that attainment. Translated to the political, the demand for this new man means the will to break from all outmoded, artificially constructed forms in the national life: “The National Socialist movement is not the conservator of the states of the past, but their liquidator for the sake of the Reich of the future.”

In his powerful speech at the cultural conference, the Führer widened the frame of this will for the reestablishment of the German political order to include the emerging meaning of National Socialism’s worldview as the “heroic doctrine of the valuation of blood, of race, and of personality, as well as the eternal laws of selection.” And at the end of this fundamental address, this sentence: “This new state will give a very different attentiveness to the nurturing of culture than the old did.” This acknowledgement by Adolf Hitler rang out, past all the worry and workload of reconstructing the state, as the announcement of the new German idealism—and the Führer knows that he has the people’s spiritual support in this appeal to idealistic forces, just as he won their support back then when he was preaching and practicing sacrifice for an idea from within the deepest swamp of materialism.

The Führer speaks to the party officials of their task of seeing to the political education of the people:

You, my party officers, are responsible before God and before our history for ensuring that a November 1918 will never again be possible in German history, through the political rearing of the German people toward one Volk, one idea, one expression of the will.

To his youth, Adolf Hitler speaks of the eternal fidelity of comradeship: “You must be true; you must build amongst yourselves one single, great, glorious comradeship.” However, the SA hears of the joy of victory: “The debt of our Volk is erased, its sin atoned, its shame removed, the men of November are deposed and their power is at an end.” These proud and victorious words coming from the Führer are the greatest thanks for the Brown Army for their past struggle and risk. There on the Luitpoldhain,1 before the vast brown columns of discipline, of self-sacrifice, there came also a word directed at the world abroad:

We do not need to rehabilitate our Volk’s historical honor on the battlefield, for no one took it from us there. Only one dishonor came upon us, and it came upon us not in the West, nor in the East, but on the home front. This dishonor has been rectified.

Finally, the great concluding remarks of the Congress about the political leadership of the nation; one final, gripping appeal to the fighters of the movement, to whom the Führer again gave the explanation of the National Socialist fight and the National Socialist mission:

If the word socialism is to have any meaning at all, then it can only mean to assign to everyone—with iron fairness and deepest insight—that part of the preservation of the whole that accords to his inborn disposition and consequently his worth.

With this creed of ultimate service to the Volk and the state, the Party Congresses of the victory of the NSDAP ended. At no moment was the Congress at a triumphal and satisfied rest, but rather always a challenge and a call to new obligation.

“The future will one day weigh us in the same measure as we thought of it. Therefore, may our God guard us against making those mistakes founded in human self-interest.” With these words from the Führer, National Socialism went forth out of Nuremberg into the continued fight.

—Dr. Walther Schmitt

THE PROCLAMATION OF THEFÜHRER AT THE OPENING OFTHE 1933 PARTY CONGRESS

When the National Socialist movement was called into life in 1919 to establish a new Reich in place of the Marxist democratic republic, this undertaking seemed utter foolishness. Thanks to their superficial historical education, those sophistical intellectuals could, at most, bring themselves to offer a sympathetic smile.

Most of them well recognized that Germany had run into hard times. The majority of the so-called national intelligentsia had quietly grasped that those who held power in the November Republic were partly too evil and partly too incompetent to successfully lead our Volk. The one thing they did not recognize was that the new regime would not be overcome by the same forces that for fifty years shrank from the attack of Marxism, only to wretchedly capitulate to it in the hour of greatest need. Maybe it also was in the nature of the personal decrepitude of the earlier political leadership. They were unable and unwilling to recognize the timescales necessary for the restoration of a people’s strength.

That we National Socialists could see the requirements for overcoming Marxism, and also worked toward this overcoming, divorced us from the bourgeois intellectual world.

The first requirement revealed itself with the insight that a power that is determined to kill the mind through terror will not be broken by the polite opinion that terror can be overcome by the mind. It makes sense to employ purely intellectual tactics only so long as all segments of the population are ready to submit to the outcome of such an intellectual wrestling. The moment Marxism launched the mob slogan “If you won’t be my comrade, then I’ll smash in your head!” they declared the rule of force. The mind can either resist with equivalent weapons or else lose its influence and become historically irrelevant.

Furthermore, it is clear that one cannot expect anything different from a movement than what it held up to be engraved and innate through the course of its coming-to-be. Bourgeois parties could venture so little outside their traditional mentality; likewise, Marxism had to hew to Marxist dogma. This means it is a fallacy to believe that party structures that have been dueling for decades with more or less pitiful intellectual weapons can suddenly do heroic deeds. It is likewise a fallacy to expect that Marxism would ever renounce its terroristic inclinations.

This is also the reason that one must not think that old and stale organizations can be directed toward new ends, even if they are headed by new leadership. You cannot coax powers out of an organization that does not possess them. The spirit that birthed it and ruled its development searched, found, and gathered a people fit to its character. He who, like Clausewitz said, makes “false cleverness” the ruling law of his movement cannot hope to one day discover heroic fanatics among it. It was therefore folly when, in the years 1919, 1920, and after, men who recognized the distress of our Fatherland believed that a switch in the leadership of the bourgeois parties would suddenly lend these the strength to annihilate the internal enemy. Quite the opposite: every attempt to give the bourgeois parties leaders who were not characteristic of them lead to a split between leadership and party members. When for seventy years you glorify a false democracy, you cannot in the seventy-first year grasp for dictatorship. Such attempts lead to comical experiments. Seeking help, one borrows the principles of others without believing in them. Hence bourgeois parties that vote themselves a dictator, under the condition that he never dictates!

The opposition to Marxism therefore required from the beginning an organization whose entire being was made for and suited for this fight. But this required time to emerge. Just by looking at the aged political leadership of the bourgeois antipodes of Marxism, one can find the key to the consistent incomprehension of this class for the methods of the young National Socialist movement. With few exceptions, age kills not only physical, but also intellectual potency. Because everyone desires to experience the fruits of his fights himself, he seeks the easier (because quicker) methods of actualizing his ideas. Not comprehending any organic development, rootless intellectualism seeks to bypass the laws of growth through quick experiments. In contrast, National Socialism from its first day was ready to take on the dreary, long work of rebuilding the instrument with which we hoped to finally destroy Marxism. Because this path was not grasped by the superficial mentality of our politicizing bourgeoisie, the young movement could at first only develop through those classes that had stayed intellectually unspoiled, uncomplicated, and therefore closer to nature. What the wisdom of the wise could not see was understood by the soul, the heart, and the instinct of these primitively naive and healthy people! Among our tasks for the future is the necessity of crafting a union between feeling and reason again—in brief, to raise that untainted generation that will recognize the eternal lawfulness of development with a clear mind, and with this deliberately find its way back to primitive instinct.

While directing its plea for the formation of a new movement to the broad mass of our Volk, National Socialism had to first suggestively burn into the minds of the few people it had already won over that they can eventually be the saviors of the Fatherland. This problem of teaching self-confidence and faith in the self was as important a goal as it was a difficult one. People who, on the basis of their social and economic heritage, mostly occupied the lower and often hard-pressed classes had to be imbued with the political conviction that they would one day be the political leadership of the nation. The fight that the National Socialist had to engage in, against such a greatly superior force, obliged us to strengthen his trust in the movement and his self-confidence by all means available. The bourgeois world constantly found scorn and derision for our method of implanting what they called the “presumptuous megalomania” of one day leading the Reich. And yet, fanatic faith in the victory of the movement was the prerequisite for every later success. The most psychologically effective part of this upbuilding, besides the practice of the daily struggle and getting used to the enemy, was the visible demonstration of belonging to a great and strong movement! Therefore, our rallies not only won more adherents, but above all they solidified and morally strengthened those already won. While the ingenious leaders of our bourgeois world talked about the “work in secret,” and at best delivered profound discourses at tea parties, National Socialism began its march into the Volk. We held hundreds of thousands of rallies. A hundred and a hundred thousand times our speakers were in assembly halls, small smoky pub rooms, and the great sports arenas and stadiums. Each rally not only won us more new people, but first and foremost solidified everyone and filled everyone with that suggestive confidence that is the prerequisite for every great success. The others spoke of democracy but shunned the Volk. National Socialism spoke of authority, but fought and wrestled alongside the Volk like no other movement before it.

Hence, the Party Congresses of the National Socialist movement were never comparable to those squabbles of quarrelsome parliamentarians and party and union secretaries who gave their seal of approval to other parties’ meetings.

The points of the National Socialist Party Congress were: firstly, for the Führer of the movement to once again have the opportunity for personal acquaintance with the party leadership; secondly, to renew the bond between the party members and their leadership; thirdly, to strengthen everyone’s confidence in victory; and fourthly, to set forth the great spiritual and psychological impulses for the continuation of the fight.

In 1920, 1921, and 1922, the first Party Congresses took place. They were expanded general-membership meetings of the party, which was then almost exclusively limited to Munich and Bavaria.

It was also Munich that, on January 27th, 1923, experienced the first Party Congress, with representatives from the rest of Germany. By November of that year, the party was banned.

Three years later, we celebrated the memorable resurrection of our party in Weimar.

In 1927, the third Party Congress took place, and this time for the first time in Nuremberg, as did the fourth Party Congress in 1929.

Then, when for several years no Party Congress could take place, it was not our fault, but rather due to the conduct of others. The attempt to gather in Nuremberg again in 1930 ran aground against the resistance of our political opponents, who were then the Bavarian government. For three years this bourgeois conservative government sabotaged any further attempt at meeting. But for the movement and for all time henceforth, the place of our Party Congress shall be the city in which we first, with a powerful announcement, proclaimed the new German will.

September 2nd will mark ten years since, for the first time in Germany since the shameful collapse, there was in this city an overpowering march led by National Socialism. This march not only whipped up the cheering Franconian city, but was received by all of Germany as the sign of a coming turning point!

In order to give the movement a feel for the honorable tradition of our struggle, the Party Congress will for all time take place here in this city!

Thus, you were called here to the fifth Party Congress of the NSDAP, the first in the New German Reich!

A miracle has occurred in Germany. What we hoped for in the long years of struggle, what we believed within our breasts, what we were ready to give any sacrifice to achieve—even our own lives—has now become reality!

The National Socialist revolution has defeated the state of betrayal and perjury, and has in its place restored a Reich of honor, loyalty, and decency. The bulk of the people joined us, so we did not have to carry out this revolution as leaders of the “historical minority” against the majority of the German nation. We were happily relieved that the overwhelming majority of the German Volk came to recognize our principles already before the turning point of destiny. Thus, it was possible that one of the greatest upheavals of power could happen with almost no bloodshed. Thanks to the shining organization of the movement, the instrument of leadership at no moment slipped out of hand during this historic upheaval. Besides the Fascist revolution in Italy, no similar historic undertaking can be compared in its inner discipline and order to the National Socialist uprising. We feel it as a great fortune that today the overwhelming majority of the German Volk stands with us in loyal attachment to the new regime. It is good and advantageous to know there is power in one’s fists, but it is better and happier to be able to call the love and assent of a people one’s own!

And as you are gathered here in this hall, millions of German men and women and today’s youth live with us. The National Socialist revolution has become the German Reich, the German state. Behind the flag of our former opposition, the German nation marches!

And this is also the surest guarantee of the ultimate success of our work.

Just as the sick man cannot be healed by the physician’s arts alone if his body mounts no resistance to the death knocking at its door, if even the will to life is extinguished, so also a people cannot be spared of its destruction by political leadership alone if it either has become worthless in its inner substance, or if the political leadership does not succeed in awakening the will of all and enlisting them in this task. The joyful participation of the mass of the nation does not only regain its freedom, but economic problems are also unsolvable without the regime’s measures having the trust and support of the whole Volk. The situation in which we find ourselves is clear to everyone. At the beginning of this year there were weeks in which we avoided the precipice of Bolshevik chaos by a hair’s breadth. The threatening political situation arose from the more than slightly dangerous economic condition. The rapid crash last winter seemed like it would grow into a total collapse. When the great historian Mommsen described Judaism as a “ferment of decomposition” in public life, this decomposition was already far advanced in Germany. And as a single human can spread a sickness to a stadium, where it would be difficult or impossible to reverse, so it is in public life. So, with grim determination, National Socialism took up arms in defense against the creeping “decline of the West,” carried by the belief in the not-yet-totally-destroyed great inner values that are inherent to the civilized people of Europe, and which are especially apparent in our German people. When Fascism gave the example with its great historic deed of saving the Italian people, National Socialism made it its mission to do this also for the German people. For this reason, we will not tolerate the enactors of our people’s former destruction continuing to make our people spineless—or even just unsure—through their eternally negative operations of degradation, especially at a time when our people’s whole will must help to avoid catastrophe and overcome the crisis. Therefore, it will be one of the most important tasks of our movement to declare a relentless war against the destroyers of our people’s strength and to wage it until their utter annihilation or submission. As the sole wielder of state power, the party must recognize that from now on it alone carries the whole responsibility for the course of German destiny. In view of the international spread of the primary ferment of this decomposition and the special dangers to Germany resulting from this, we will all the more have to ensure that the spirit of doubt, of diffidence, or of self-indulgence is banished from within our people. We National Socialists went through too long a period of persecution and suppression to not recognize the actual value of the glitzy democratic slogans of our political enemies. We are determined to act accordingly! The educational work the movement will have to do is tremendous. For it is not enough to organize the state according to certain principles; it is also necessary to nurture them in the people. Only when the Volk inwardly takes part in the foundations and methods that carry and animate its state organization will a living organism arise, instead of a dead and merely formal and mechanical organization.

When necessary for self-preservation, only that which is filled with life will be able to lay claim to and issue life.

Among those problems brought to us to solve, the most important is the overcoming of unemployment. We do not see its danger as purely material. The effects of distress show themselves in the lives of the people in various ways. Weak-willed surrender alternates with desperate vigor. The material preservation of one part of the nation which cannot find work—at the expense of that part which can find work—can only have negative results in the long term. It is neither logical, nor moral, nor just to take away a part of the fruits of the labor of the working part of a people in perpetuity. Rather than take away the results of work, it would be logical to distribute the work itself. No one has the moral right to require that others work so that he himself does not have to work. Rather, everyone only has the right to demand their state organization to find the means and solutions to let work be available to everyone! We will have to exert ourselves tremendously to solve this problem in a responsible and useful way. Within just a few years we will have to set right the foolishness and recklessness of decades. We will do this when we succeed in forcing the nation to a lively participation in this tremendous undertaking. This is all the more necessary because numerous other projects have to step into the background so that all our strength can be focused on solving this one problem. We are traveling down roads that have hardly been trodden historically. All crises up to this point cannot be compared to our current economic deterioration, as they fail to live up to it either in their magnitude or their extent, or else they are too far from us in time, so that no detailed enough study can be made to get a clear picture of the methods used to correct them. Because of this, it is always a possibility that this or that measure we enact will not prove effective; but for this reason it is all the more necessary to prevent the nagging criticism that is forever bent on subversion! It is irrelevant if a thousand critics live, but it is not irrelevant if because of them a people collectively renounces its life and perishes. All those men who through their insane or criminal behavior since November 1918 thrust us into our present misfortune and who used the phrases “liberty,” “fraternity,” and “equality” as the leitmotif of their dealings do not today share in the fate and sorrow of the victims of their politics! Through them, millions of German comrades were delivered into the hardest bondage that there is. Their very being was raped by hardship, misery, and hunger. The seducers certainly enjoy their freedom in foreign lands to take foreign pay to slander their own people, to dole out hate; yes, they would like for them, if possible, to be mowed down on battlefields as defenseless cannon fodder! That these men’s spirits once and for all disappear from Germany is one of the National Socialist movement’s greatest duties, and a prerequisite for the convalescence of the German people. May our common sense and our determination for all time prevent our Volk from losing our unity of thought and will for the sake of the catchphrase of “the right to free criticism.” With this it would be abandoning the best thing that it possesses. If we believe in the resurrection of the German nation, it is not because this type of rootless critic instilled confidence, but only because we believe in the healthy kernel of our Volk.

The average German has always been better than the most excellent of Marxist subverters!

This Party Congress, too, thus has the high duty to strengthen and cement the wonderful confidence of our people. The active party militant who had the good fortune to be able to take part in this conference must go forth with his newly strengthened confidence into his social circle and work as an apostle for the National Socialist idea and National Socialist action. The German people, having faithfully entrusted their fate to the movement, will be happy to see the firmness and self-assurance with which the movement determines the way.

The ascent and finally the stunning victory of the National Socialist movement never would have happened if we had tolerated the principle that in our ranks each can do as he wishes. This habit of democratic permissiveness can only lead to uncertainty, dissoluteness, and ultimately to the decline and deterioration of every authority. The argument our opponents make, that we ourselves once made use of these rights, is untenable. We made use of an unreasonable right, which was an inextricable part of an unreasonable system, in order to topple this system on account of its unreasonableness. Nothing falls which is not ripe for falling. When the old Germany fell, it proved its own internal weaknesses, just as the November Republic’s fall makes its weaknesses plain for all to see. We would only lack the right to fight with these weapons if we planned to let ourselves succumb to the very same illogic and weakness!

Through its work of politically educating the German people, the Party will have to make the German man more and more spiritually immune against any relapse into this past. While we negate the democratic parliamentary principle, we most acutely represent the right of the people for the determination of its own life. We alone recognize that the parliamentary system does not actually express the will of the people, which, logically, can only be a will for the preservation of the people; rather we see in this system a distortion, if not a total inversion of the people’s will. A people’s will to assert its existence appears in its clearest and most useful form inside the heads of its best! They are the representative leadership of a nation, and they alone can be the pride of a people; never can it be the parliamentarian, whose birthplace is at the polls and whose father is the anonymous ballot. It will require years to build up the most capable minds into the future leadership of the nation. The corresponding education of the people will take decades.

If our movement’s Party Congresses have so far been an exemplar of organization and discipline, this is only because the movement knows that it can require nothing of its followers that it does not do itself. Only in applying the principle of authority and discipline straight down from top to bottom in the party’s organization does it win the moral right to ask the same of even the lowest comrade. And it must do this! For the greater the challenges that these times pose, the greater the authority that has to be commanded by whoever will have to solve them. It is important that our organization’s leadership has such self-assurance in its resolutions that it instills unconditional confidence in party members as well as followers. For the people will rightly never understand it if its leadership, having failed to straighten out problems, suddenly lays these problems before the people for them to discuss and provide clarification. It makes sense that even very wise men may fail to reach complete clarity on especially difficult problems. However, it would be a capitulation of leadership as such if it opens up exactly these problems to public treatment and commentary. In doing so, it esteems the broad mass as having more power of judgment than the leadership itself. Then it should also go along with the consequences and, logically, turn over leadership to those whom it deems fitter to judge!

In opposition to this, the National Socialist Party must be convinced that it will be able to find and unite to itself the most politically talented people in Germany, thanks to a process of selection imposed by the vital struggle. This community has to follow the same law amongst itself that it wishes to see the mass of the nation follow. The party must therefore constantly nurture in itself the mental habits of respect, of authority, and the free adoption of the highest discipline if it wants to nurture the same within its following. It has to be hard and consistent. It is clear: our political enemies are defeated. Their own quality was unmasked as clearly inferior. The only thing they could hope for is, through their deft subversion, to loosen the national discipline and to shake our trust in each other and our leadership.

Let this Party Congress be a singular warning to all these tempters. This party stands here, with its organization more stable than ever, resolute in will, rigorous in self-correction, unconditional in discipline and in its respect for its responsible authority to those below, and its authoritative responsibility to those above.

Only with this spirit will we overcome all the alleged and real differences in economic and other aspects of life and solidify our Volk into one body. Only with this can you take burghers and farmers and workers and all the other classes and reconstitute one Volk!

Over the course of the thousand-year development of our Volk, German tribes and then governments started to form, and along with this development, there came to be certain entities that we still see today as our federal states. Their existence cannot be attributed to any national necessity. In weighing their pros and cons for the German nation, the former disappear in light of the latter. Even in the realm of culture, the emerging nation proved to be more creatively fertile ground. Only due to the preexisting correlations between political and cultural hotspots did we get the decentralization of German art, which has caused our Fatherland to appear so beautiful and rich. While we are determined to protect these and other valuable traditions, we must advance against these barriers to our national unity, which have done incalculable political damage to our people for centuries. What would Germany be today if past generations had done nothing against the appalling cacophony of so many little states, which never did the German people any good, but was always a boon to our enemies? One Volk that speaks one language, possesses one culture, and has experienced the formation of its destiny through one common history, can do no other than to also strive for unity in its leadership. Besides, it would lose the advantages of its numbers, while still having to suffer the disadvantages thereof. We saw at the January, February, and March conferences this year to what lows these circumstances can bring a people’s character and strength, when the smallest party-egoists coldly combined their despicable party interests with provincial regional interests and thus sought to threaten the unity of the Reich. The German nation’s first answer to these agitators against its unity and greatness was the Reich Governors Law. Fundamentally, however, the National Socialist Party must recognize the following:

The former German Reich at least ostensibly wanted to build itself up out of the individual states. But the states themselves could no longer build themselves up out of the German tribes, but perhaps at best out of individual German persons. Today’s German Reich no longer forms itself out of the German states, nor out of the German tribes, but instead out of the German Volk and the National Socialist Party, which includes and encompasses the entire German Volk. The nature of the coming Reich will therefore not be determined by the interests and perceptions of the building blocks of what is past, but by the interests of the building blocks that have constructed today’s Third Reich. Neither Prussia, nor Bavaria, nor any other state will be the pillars of today’s Reich; rather the only pillars are the German Volk and the National Socialist movement. The individual German tribes will be happier to forge this mighty unity once more than they ever could have been in their only purported former independence. For a German state of six or seven million or even more people would never be independent, but only a plaything of the more powerful influences neighboring it. Therefore, the National Socialist movement is not the conservator of the states of the past, but their liquidator for the benefit of the Reich of the future. Because the party is neither North German nor South German, neither Bavarian nor Prussian, but simplyGerman, all rivalries dissolve away as meaningless within it. The party’s task then is to educate the German Volk, the German people in this spirit, and thus ensure that further legislation will win the joyful appreciation and the will of all. And if, despite all this, this or that person decides not to understand what we are doing, then we will know how to bear it. As long as the party champions principles that are theoretically sound and have stood the test of millennia, we should not let the criticisms of the present deter us. But woe to us if—even just theoretically—it would be possible for an opposition to form with better principles, better logic, and therefore with more right. Power and the brutal application thereof can do much, but a condition is only safe in the long term if it appears to be logically and theoretically unassailable. And this above all: the National Socialist movement must adopt that heroism that prefers every adversity and every hardship over even once forsaking a principle that it has deemed right. There is only one fear that may enter the movement’s heart, and that is the fear that a day might possibly come that would find it untruthful and thoughtless. Whoever wants to save a people must think heroically. The heroic thought must constantly be ready to relinquish the assent of the present age when truth and honesty demand it. As the hero relinquishes his life in order to live on in the pantheon of history, so a truly great movement must see in the rightness of its idea and in the honesty of its dealings the talisman that will surely guide it from the passing present into the undying future.

It was only a few weeks ago that the decision was made to hold the first Party Congress in the same year as this, the year of our victory. This grand organizational improvisation was accomplished in hardly a month. May it serve its purpose to increase the manpower of the party as it shoulders the burden of German destiny, to strengthen our resolve to enact our principles, and to bring into greater consciousness the unique meaning of this phenomenon. Above all, let the nature of this rally reaffirm that the leadership of this nation may never ossify into a purely administrative machine, but that it must stay a living leadership—a leadership that does not see the Volk as an object for its manipulation, but a leadership that lives in the Volk, that feels with the Volk, and that fights for the Volk. Forms and establishments come and go. What stays and should stay is this living substance of flesh and blood suffused with its own essence, as we know and love our Volk. Both physically and spiritually, our continued existence is dependent on the endurance of our Volk. We wish for the endless earthly existence of our Volk, and we believe that by fighting for this we are obeying the Creator’s command, who planted the drive for self-preservation deep within all beings.

Long live our Volk!

Long live the National Socialist Party!

THE FÜHRER’S SPEECH AT THE CULTURAL CONFERENCE

On January 30th, 1933, the National Socialist Party was entrusted with the political leadership of the Reich. By the end of March, the revolution came to an end, on the surface—an end as far as the complete takeover of the reins of power. But only he without any inner understanding of this immense struggle could think that this means the end of the great struggle between competing worldviews. That would only be the case if the National Socialist movement merely had the same aims as all the other customary parties. These regard the takeover of political power as the zenith of their existence. But worldviews see the acquisition of political power as just a precondition for the completion of their actual mission. Within the very word “worldview” lies the solemn proclamation of the decision to view all things through the understanding that flows from within it. Such an understanding can be right or wrong. It is the basis for every opinion on all phenomena and occurrences of life, and it is a binding and obligatory law for every action. So, the more such an understanding places itself under the natural laws of organic life, the more useful its conscious application will be for the life of a people.

Consequently, the unspoiled, primitive Volk has the most natural worldview in its instincts, which lets it automatically take the most natural, and therefore most useful, stance on all relevant questions of life. Just as the healthy, unspoiled individual conjures up from his innermost self a totally unconscious natural reaction that gives him the most appropriate stance toward the questions that deeply move and challenge him, so also the healthy Volk will instinctively find within its drive for self-preservation the reaction to all of life’s challenges, a reaction that is most appropriate to its needs. The equality of life-forms of a certain kind thus formally spares the formation of binding rules and compulsory laws.

Only with the physical mixing of inwardly diverse individuals do attitudes get confused. This necessitates rules and laws to let such a people speak with one voice, which otherwise has fragmented and diverse reactions to the influences and demands of life.

Because the types of people that Providence has willed and made different have not been given the same purpose, when these mix, it is decisive for the conduct and composition of the life of such a mixture which of the parts’ inborn attitudes are made compulsory in the different areas of the struggle for existence.

All historically verifiable worldviews are only understandable in their relation to certain races’ attitudes toward and purposes in life. Therefore, it is very hard to take a stance on the rightness or wrongness of such attitudes when you do not test their effects on the people to whom you would like them applied.

What would be the most natural and appropriate expression of life for one people, for whom it is inborn, for another alien people may become, under some circumstances, not only a serious threat, but even perhaps the end.

In the long run, there is no nation assembled from various racial nuclei that can hold two or three different points of view at the same time and use these to determine its life in all the most important areas or as a foundation on which to build itself up. Sooner or later this necessarily leads to the dissolution of such an unnatural union. If this is to be avoided, then which racial component will assert its character and worldview is crucial. This will determine the trajectory of such a people’s further development.

Every race asserts its existence with the powers and values that are natural to it. Only the man suited to heroism will act heroically. Providence gave him the preconditions for it. Those who are by their nature purely matter-of-fact as well as physically unheroic beings express only unheroic traits in the course of their struggle for life. As much as the unheroic element of an ethnic community can drag the heroically disposed toward the unheroic and thereby make them renounce their innermost being, so also can the decidedly heroic purposefully subordinate contrary elements to its disposition.

National Socialism is a worldview. By gripping those people who by their innermost disposition also belong to this worldview, it becomes the party of those who, by their character, can actually be attributed to a certain race. It acknowledges the reality of the different racial substances in our Volk. It also is far from rejecting this mixture, which forms the overall pattern of our Volk’s expression of life. It knows that this inner racial arrangement of our Volk determines the normal span of our capabilities. However, it wishes for our Volk’s political and cultural leadership to preserve the face and expression of that race which, through its heroism alone (thanks to its inner disposition), turned a conglomerate of different components into the German Volk in the first place. National Socialism confesses a heroic doctrine of the valuation of blood, of race, and of personality, as well as the eternal laws of selection. With this, it stands in unbridgeable contrast to the worldview of pacifist international democracy and its effects.

This National Socialist worldview necessarily leads to a reorientation of almost all realms of national life. Today we cannot yet begin to estimate the magnitude of the effects of this tremendous intellectual revolution.

As the relationship between conception and birth became clear only after a long course of human development, so the meaning of the laws of race and its inheritance are today only beginning to dawn on humanity. This clear recognition and conscious consideration will one day serve as the foundation of future development.

Proceeding from the recognition that in the long run all created things can only be preserved by the same powers that once created them, National Socialism will ensure that the character of those components that formed the German national body over the course of many centuries will have the greatest influence and most visible effects within the German Volk.