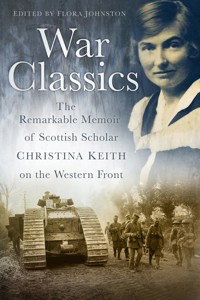

War Classics E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Christina Keith came from the small town of Thurso on the far north coast of Scotland. Highly intelligent and ambitious, she became a lecturer in Classics at a time when that was still a brave and unusual choice for a woman. Towards the end of the First World War she left behind the sheltered world of academia to live and work among soldiers of all social backgrounds as a lecturer with the Army's education scheme in France. She writes with warmth and humour of her experiences. When she and a companion travel across the devastated battlefields, just a short time after the guns have fallen silent, her descriptions are both evocative and moving. This unique memoir is an unforgettable read.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 382

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FLORA JOHNSTON has a First Class Honours degree in Scottish History and a postgraduate qualification in Museum Studies. She worked for six years for the National Museums of Scotland on the development of their prestigious Museum of Scotland and now researches and writes historical material for publications, interpretation panels and multimedia. Her third book was published in 2012 by the Islands Book Trust, Faith in a Crisis: Famine, Eviction and the Church in North and South Uist.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the trustees of the Kerr-Fry Bequest for the grant which allowed me time to work on Christina’s manuscript and to carry out research in some of the places which were part of her story.

Archivists and librarians from the schools, universities and towns which featured in Christina’s life have helped me to piece together her story, and I am grateful for help received from the following organisations: Castletown Heritage Society; Caithness Archive Centre, Wick; Edinburgh University Library; St Leonard’s School, St Andrews; Newcastle University Library; Birmingham University Library; St Hilda’s College, Oxford; Newnham College, Cambridge; Dieppe Ville d’Art et d’Histoire; The British School at Rome. I’m also very grateful to my agent, Robert Dudley, for his enduring faith in Christina’s memoir.

The extracts from the diaries of John Wight Duff are reproduced by permission of the librarian, Robinson Library, Newcastle University.

The images from the YMCA collections are reproduced by permission of Special Collections, University of Birmingham and of the YMCA.

The letters of David Barrogill Keith are reproduced by permission of the Highland Archive Service, Caithness Archive Centre.

Particular thanks to my father, Peter Keith Morrison, for starting this whole project off by showing me Christina’s memoir, for giving permission for its publication, and most of all for his many, many stories and reminiscences over the years which have fuelled my interest. I’m also grateful to his sister Joy and cousin Sheila for sharing their memories of the Keith family and of time spent in Thurso. My own family too have had to put up with my obsessions, and so thanks are due to Elizabeth and Alastair, and to David, who only once said as we pulled into another obscure French destination, ‘It’s like going on holiday with Christina!’

But most of all, thank you to Christina for writing all this down in the first place. I hope I have done your memoir justice.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part 1: Christina’s Story

1 ‘Living with the ancestors’

2 ‘An Edinburgh and Newnham girl’

3 ‘How fine their sense of duty has been’

4 ‘The meeting of mind with mind’

Part 2: Christina Keith’s Memoir: A Fool in France

1 How I went out

2 Delays at Headquarters

3 London before embarkation

4 France and her welcome – Dieppe

5 Life at a base – who wants to learn?

6 Work and play

7 Officers and men

8 At a base hospital

9 Up the line to Amiens – the best days of all

10 The forward areas and Cambrai

11 To Albert, Arras and Vimy

12 Closing down

13 L’Envoi

Afterword

Appendix: David Barrogill Keith

Sources and further reading

Copyright

Introduction

I never knew Christina Keith, but she was my grandmother’s eldest sister. She died in 1963, just a few months after my parents became engaged. In her will she made a gift to my father, her nephew, ‘to help him start off in his married life’.

In our family home there was an exceptionally long bookcase, which caused problems to the removal men each time we moved house. That bookcase had belonged to Christina Keith, or ‘Auntie Tiny’ as she was known within the family. She was one among a host of legendary relatives whose names I knew, an intellectual who was somewhat eccentric and took her tins to the nearby hotel to be opened because she couldn’t use a tin opener.

That was largely the extent of my awareness of Auntie Tiny until November 2011, when my father first showed me her manuscript memoir from 1918 to '19. In this short book Christina, using the pseudonym ‘A Fool in France’, recounts her experiences as a young lecturer to the troops in France at the end of the First World War. It is a story in two parts. In the first she recalls life at the base among men who were desperate to be allowed home, while the second part describes an astonishing journey which she and a female companion took across the devastated battlefields just four months after the Armistice. From the moment I read the memoir I was captivated. I wanted to know more about Christina, her life, her background and the scheme which had taken her to France. Here was a truly fresh insight into life in France as the First World War came to a close.

I am glad that Christina wrote down her experiences. She disguised the identities of those about whom she wrote, which suggests that she always intended her story for wider circulation, and her brother appears to have tried to find a publisher for the book after her death, but without success. Yet now, a century later, Christina’s story is worth telling for a number of reasons. Firstly, despite the fact that the First World War is one of the most-discussed periods in recent history, Christina describes aspects of that time which have never been particularly widely known, saying herself, ‘I suppose we were one of the freak stunts of the War. You have probably never heard of us and would not have believed us true if you had.’

She travelled to France as part of the army’s education scheme, which was implemented by the YMCA. Based in Dieppe, she observed at first hand the workings of the ‘Lines of Communication’, the immense logistical infrastructure which existed behind the front line during the four years of conflict. The fighting armies needed to be supplied with weaponry, clothing, food and equipment, which involved drivers, engineers, bakers and clerks among many others. The Remount Service supplied and cared for the horses which were still an intrinsic part of the army during this conflict. The tremendous feat of organisation involved in the Lines of Communication contributed hugely to the British Army’s ability to sustain and ultimately prevail in such a prolonged conflict, yet the role played by tens of thousands of men and women behind the lines has generally been overlooked in favour of the more dramatic, glorious and tragic stories from the front line.

Christina set out for this world of base soldiers, rest camps and service huts in October 1918, just in time to participate in the newly launched education scheme. There had been educational provision for the men throughout the war, although not on the scale of this new scheme. The YMCA had played a significant role in caring for the physical, spiritual and emotional needs of the men since the outbreak of war. From officers’ rest clubs in French towns to huts in army camps where female volunteers served tea and provisions to the men, from reading rooms and organised sports to the provision of accommodation near hospitals for the relatives of wounded soldiers, the YMCA’s contribution to boosting morale touched men right across the army, and yet is little remembered today.1 We are familiar with accounts of the trenches, but Christina’s narrative sheds light on a parallel existence which was taking place only a few miles from the front line. Most soldiers moved between these two interdependent scenes, two parts of the same whole which made up the British soldier’s experience of northern France in the First World War.

And yet Christina’s story is more than simply a picture of life behind the lines. In March 1919, with four days’ leave, she and a female companion (known only as ‘the Hut Lady’) managed to negotiate permission to travel by train into the War Zone. Her ambition was to ‘see where my brothers have been and all the things they’ve never told me of these weary years’. This remarkable journey of two British women across a devastated landscape provides a vivid and compelling eyewitness account of a world which can only have existed in that form for a very short time.

The names of the places they visited – Arras, Vimy Ridge, Thiepval, Cambrai – are today still synonymous with slaughter. French refugees were living in abandoned army dugouts. Tanks, clothing and weaponry lay littered across the battlefield. The war graves were not grassy fields with neat white lines of stones, but groups of rough wooden crosses stuck in yellow mud and water. The sense is of a land which, now that the guns had fallen silent, was stunned by what had happened to it.

Few women had reached these parts, a fact emphasised by the surprise and delight with which Christina and her friend were met by soldiers at every turn. They knew they were privileged to pass through the army zone before much of the debris had been cleaned up – ‘while it is like this and before the tourists come’, said the Hut Lady. Christina described those four days as ‘a dream-world, where everything happened after the heart’s desire on a background of infinite horror’.

Christina’s manuscript thus draws our attention to people, places and events which are half-forgotten, but what is even more remarkable is the perspective from which this narrative is written. There are many first-hand accounts of different facets of the First World War – the rise of general literacy levels ensured that this conflict was documented on a personal level to an extent that had never happened before. However the majority of diaries, letters and memoirs are, naturally, by men. There are several vivid accounts by nurses working in clearing stations and base hospitals, but Christina was a very different woman to these – and would probably have made a terrible nurse! Christina was an intellectual, a high-flying academic from a generation which was breaking down barriers in women’s education. She had spent most of her adult life in the cloistered, middle-class environment of academia, living in all-female residences, and was accustomed to teaching university-level students. In 1918 she found herself in the male-dominated world of the army, meeting, working with and teaching men of all abilities and all classes, with a keen eye to observe all that went on around her. Hers is a truly fresh perspective on the events of the period.

Christina’s perspective and her frankness give us an insight into the attitudes held by those of her background at that time, and some of those attitudes can surprise us and even make us feel rather uncomfortable today. Christina came from a class and a generation which were still strongly tied to the Victorian values of the era into which she had been born. Thus, although she was a woman who clearly had no intention of letting her gender limit her academic potential, she was not a feminist as we might see it today. She took a pride in not conforming to what might be expected of a woman, referring to herself as ‘a bluestocking who had never cooked a dinner in her life’, yet she still expected men to treat her in a particular way, and was offended when they did not – as for example with the American soldiers who did not move their belongings to make more space for her on the train. She was perfectly willing to adopt the persona of a helpless female if she felt it would help her get her way.

Early twentieth-century society was very clearly divided along class lines, and perhaps nowhere was that emphasised more explicitly than in the army, with the division between officers and other ranks. Throughout her narrative Christina wrote with warmth and respect about the ordinary British soldier, and there is no doubting the admiration she had for the men she met – but equally there is no missing the paternalistic tone, and the breadth of the chasm which existed between her own world and the lower classes. At a time when the Russian Revolution was frighteningly recent and the military powers were constantly watchful for signs of mutiny in the ranks, those in authority were expected to reinforce social hierarchies, and Christina’s colleague who dared to give secret lectures on socialism was quickly removed.

Christina’s narrative reveals much about prevailing attitudes to gender, to class and also to race. With regard to her own nationality Christina was a passionate Scot, missing no opportunity to identify with other Scots and to praise her own people and traditions. Perhaps influenced by Sir Walter Scott, of whom she would later write a biography, the more tartan and Highland the better! And yet in an apparent contradiction she frequently referred to herself as an Englishwoman. It seems that in the days before nationalism had become a significant political force in Scotland, Christina was using ‘English’ interchangeably with ‘British’. And there was absolutely no doubt in her mind that the British were the greatest race on earth.

In the immediate aftermath of the war it is perhaps not surprising that her attitude to Germany was scornful and even offensive. Once again this reflects the widely held mood of the nation, reinforced by the press. What is perhaps more surprising is that this scorn was not merely reserved for the enemy but also for Britain’s allies. The Germans are referred to throughout as ‘the Boche’, the Chinese labourers as ‘Chinks’. The French are careless and cruel to animals, the Portuguese are ‘the worst-behaved of all the Allies’, and the Americans are dismissed as selfish and unreliable. Only the Australians and the Canadians – notably both loyal members of the British Empire – seem worthy of her respect. British imperialistic superiority was alive and well. As she came up alongside men and women of different social backgrounds and from different nationalities, Christina was candid in her opinions and thus reveals to us much about attitudes which were commonplace in the early twentieth century.

But alongside all the interesting historical information we can glean from her writing, Christina’s narrative is worthy of a wide readership because of the simple humanity of her story. Here is a woman who lived through the war, whose brothers served in the fighting and who lost people dear to her, but who says little of her own experiences. Yet despite the sorrow and tragedy which exist as a quiet undertone, here too is a woman eager to grasp the opportunities which this war gave to her. And therein lies the contradiction, for Christina as for many others. In the midst of conflict there was opportunity. In the midst of horror there was comradeship. The cost of this war was unprecedented and appalling, but there were those for whom it opened doors – to new places, to new friendships, to new skills, or simply to a new way of looking at the world.

For Christina Keith, these six months in Dieppe were a window of freedom in a life restricted by the boundaries of convention. She revelled in meeting new people, encountering new viewpoints, welcoming a wealth of new experiences and even in having her preconceptions challenged. The enchantment of it all lay as much in the fact that she and those around her knew that this world they inhabited was a fleeting one, that they would be required to return to the restrictions and realities of British routine. They could not yet know that the magnitude of what they had lived through meant that British society would never again be the same.

Note

1. For a detailed study of the role of the YMCA in the First World War, see Michael Snape’s The Back Parts of War, 2009.

Part 1

Christina’s Story

‘Living with the ancestors’

•

‘An Edinburgh and Newnham girl’

•

‘How fine their sense of duty has been’

•

‘The meeting of mind with mind’

1

‘Living with the ancestors’

Christina Keith was born on 12 January 1889 in the little town of Thurso on the furthest north coast of Scotland. It was noon, so even on those short, dark winter days some light would have spilled in through the windows of the two-storey terraced house at 5 Princes Street as she entered the world. She was the first child of solicitor Peter Keith and his young wife Katie Bruce, born into a family which had deep roots in the Caithness countryside and a remarkable desire to reach beyond the ordinary.

Christina loved Caithness, that unique landscape with its huge skies and grey seas, where the light and the weather reflect the extremes of living on the very northern edge of mainland Scotland. She travelled far throughout her life for education, for work and for adventure, but Caithness drew her back in her retirement, and she ended her days as a writer living in the house in which she had been born. The decades in between had seen the Keith family prosper, expand and scatter, but Peter and Katie’s various homes in and around Thurso provided a focal point to which their children and grandchildren continued to return.

For this was the ancestral land. Peter’s family for generations back had lived in Castletown, a village in the parish of Olrig a few miles to the east of Thurso. He was born in 1847, the son of a tailor and the second-youngest child in a large family. Peter began his education at the local school, but this came to an abrupt halt when he was expelled for locking the dominie in the school building. He was then sent to the school of Matthew Dunnet in the nearby village of Bower. Matthew Dunnet had gained a significant reputation for education and boys were sent to him from far afield.1 Peter clearly flourished under Matthew Dunnet’s tuition, and perhaps it was partly under the schoolmaster’s influence that he came to place such a high value on education, a value which he would pass on to Christina and his other children.

After serving a three-year apprenticeship with a Thurso solicitor, Peter travelled in 1867 to Edinburgh where he continued his training with a legal firm and also studied at the university. During this time the 1871 census reveals him lodging in Bellevue, Edinburgh, with a Caithness family. Also living there was his 21-year-old sister Johanna, the youngest member of the Keith family, who was described as a student. We do not know what Johanna was studying, or where, but this is the earliest indication of a desire for higher education among the women of the Keith family. In 1871 Edinburgh University was still an all-male enclave, but a fierce campaign was being fought for the rights of women to a higher education, led by Sophia Jex-Blake who wished to study medicine. Since 1868 the Edinburgh Ladies’ Education Association had offered university-level lectures to women, with the stated aim not of training them for professions but of improving their minds. Johanna’s name does not appear in the Association’s class registers, which rather suggest rooms full of Edinburgh ladies from wealthy New Town addresses. Although we do not know where Johanna was studying, it is interesting to note that Christina’s aunt was there as a student in Edinburgh in the very earliest days of the struggle for higher education for women.2

Education was valued not just on Christina’s father’s side but also on her mother’s. Katie Bruce was without doubt a very intelligent woman. My father remembers that he and his family were in Thurso on holiday at the outbreak of the Second World War. In the uncertainty of those early months they decided to stay on in Caithness rather than return to Edinburgh. Katie took on the education of her young grandson, and when sometime later he did return to his school in Edinburgh, he was far ahead of his fellow pupils!

At the age of forty Peter Keith, now a successful solicitor, bank agent and factor to the local landlord, apparently decided it was time to get married. The story goes that he was considering one local girl and took someone into his confidence. This friend is said to have asked him if he hadn’t considered Katie Bruce – she might not have the material advantages that the other girl had, but she was a very clever young woman. Peter took the advice, and they were married in April 1888.

But what was Katie’s own story? Like her husband she was of Caithness heritage. On her mother’s side she was descended from a family of some wealth and local influence – her grandfather lived in Freswick House and farmed 200 acres. But Katie’s own childhood was not an easy one. In 1875, when she was just eleven, her father died of pneumonia, leaving her mother a widow with two children. William Bruce, whose origins were humbler than his wife’s, was a wine merchant who had expanded at some point before his death into keeping a hotel. In the 1881 census his widow was continuing to run the hotel, and her 15-year-old son was working in the bank. It might have been expected that 17-year-old Katie would be helping her mother in the hotel – but no. In another of those signposts which point forward towards the role education would play in the next generation of this family, Katie Bruce was not in Caithness at all, but was living more than 250 miles away in Great King Street, Edinburgh, enrolled in ‘Miss Balmain’s Establishment for the Board and Education of Young Ladies’.

At this time there were many girls’ schools in Edinburgh offering an education to the daughters of the middle classes. Some were larger institutions but many, like Miss Balmain’s school, were substantial private houses which took a small number of boarders and perhaps some day pupils. While their brothers were being prepared for university in academies and grammar schools, the emphasis in most girls’ schools was on languages, music and dancing. Visiting masters offered tuition in some subjects, while others were the domain of the resident female staff. In 1881 Jemima Balmain ran her school along with three other female teachers, one of whom was German. They had eight resident pupils, and four servants. Miss Balmain advertised her school in the following terms:

The number of Young Ladies received as Boarders being very limited, the most careful attention is paid to each in regard to health, moral and religious training, the preparation of their various studies, and their comfort in every respect. The First Masters attend to give instruction in all the branches of a thorough education and accomplishments, and Miss Balmain is assisted by Foreign and English Governesses. French and German conversation daily. 3

So despite difficult circumstances at home, by the age of 17 and probably earlier, Katie was living in Edinburgh in order to receive ‘a thorough education and accomplishments’, in a move which surely influenced the approach she and Peter would take to the education of their own children a generation later.

In 1888 at the age of 24, Katie married Peter Keith. The bride, the groom and their wider families all lived in or around Thurso … and yet the wedding took place far away in St John’s church, Southall, in London. Some members of the family made the long journey down to London, for two of the witnesses were Katie’s younger brother John, and William Keith, Peter’s oldest brother. Peter gave his place of residence as Thurso, but Katie said she was living in Southall. We cannot be sure what she was doing there, but the third witness at the wedding was a young woman of Katie’s own age called Mary Etherington. Mary was a teacher of music at a girls’ school in Southall which her mother, also Mary, ran. Perhaps Katie was also teaching at the school? By the time of her marriage at the age of 24, Katie Bruce had lived in both Edinburgh and London, and she would pass those wider horizons on to her own children.

After a honeymoon in Paris, Peter and Katie returned to Thurso, and Christina was born the following year. They soon moved into the Bank House, a large home built above the premises of the British Linen Bank. This was where they lived in the winter months, but they spent their summers in ‘The Cottage’, above the shore beside Thurso Castle, where Peter Keith was factor to Sir John Tollemache Sinclair.

In 1913 Peter Keith purchased Olrig House, which was the ‘big house’ in the parish in which he had grown up, but by this time Christina was living away from Thurso. Many years later, writing to her mother, Christina said, ‘I love the Cottage – it is quite the nicest house we have.’ She was conscious of the influence her childhood surroundings had had on her. She remembered how her father, who had been factor to the owners of Barrogill Castle (now the Castle of Mey) for many years, had stepped in when the castle and its contents were to be sold, and had purchased portraits of the 14th Earl of Caithness and his first wife, the Countess Louise, after whom he and Katie had named their second daughter. These portraits hung on the walls in the Bank House:

So the portraits moved to another home, to be landmarks for other children, who found, to their surprise, a subtle atmosphere of gaiety and splendour and high distinction somehow wafted from their presence. Living with ‘the ancestors’ had nothing everyday about it. They swept you up into their own lively world.4

The family grew. When Christina was two, her little brother David Barrogill, known in the family as Barr, was born, followed the next year by Catherine Louise. Barrogill and Louise would both follow their father into law and would practice in Thurso. Barrogill later became Sheriff Substitute in Kirkwall, but his first love was art, and while training to be a lawyer he also studied painting at the Académie de l’Écluse in Paris and drawing at Edinburgh College of Art. Barrogill too had absorbed the family passion for an education which was genuinely stimulating. Writing for his school’s former pupils’ magazine (which he helped to found), he observed:

Education has become too lop-sided – so much attention is given to memorising, so little to thinking. This cannot but adversely affect individuality. Burns would never have been Burns if he had been a slavish imitator of Shakespeare.5

In qualifying and practising as a lawyer in the 1920s Louise, like her older sister, took her place in a world which had very recently belonged exclusively to men. The John o’Groats Journal from December 1928 illustrates Louise’s achievement perfectly. A photograph of the Caithness Society of Solicitors, taken at Olrig House during a garden party, shows Louise surrounded by thirteen male colleagues including her father Peter and her brother Barrogill. The photographer has positioned her in the centre of the group, his eye drawn perhaps to the dramatic contrast created between her simple, light-coloured blouse and hat, and the dark suits of the men. It is a desperate tragedy that Louise, the lightness amid the sobriety in that image, would die within a year of the photograph being taken.

Peter and Katie’s next two children were both daughters, Julia and Mildred. They too studied at Edinburgh University and both worked in Paris as typists at the peace conference at the conclusion of the First World War, living in the Grand Hotel Majestic. They regularly saw the leading political figures of the day, including Lloyd George, Churchill and Marshal Foch, at dinner, and witnessed first hand many momentous events such as the victory parade through Paris in 1919. When Christina hoped to visit ‘my sister in Paris’ from Dieppe, it was Julia and Mildred she had in mind. Julia later returned to Thurso, but Mildred’s long career would take her to cities including Warsaw, Prague and Buenos Aires. She wrote each week to her mother, and those letters today offer a fascinating chronicle of Foreign Office diplomatic society between the wars.

Of the four youngest children, William had a successful career in the navy, and my grandmother Patricia shared Barrogill’s passion for painting, studying at art college. Archibald died as an infant in 1904. Edward, the youngest, was born in 1908, and thus was nearly twenty years younger than Christina. He too followed a successful legal career.

Scattered as they were, Katie wrote to each of her children every week and kept many of the letters they sent in reply. There were the burdens, strains and disagreements of life in a large family. There is no doubt Peter and Katie put a great deal of pressure on their children to succeed academically, and that pressure perhaps suited some of them more than others. All the children were encouraged to achieve, but it was Christina, the eldest, whom the family believed to be truly exceptional. In the daily routine of family life this led to some irritation, as she was exempted from chores which the others were expected to perform, but above all they were proud of her. Christina, the eldest, was the pioneer.

Notes

1. Henrietta Munro, ‘A Caithness School in the Early Nineteenth Century’, Caithness Field Club Bulletin, 1981

2. Records of the Edinburgh Ladies’ Education Association, Edinburgh University Archives

3. Edinburgh and Leith Post Office Directory 1880–81

4. Christina Keith, The Romance of Barrogill Castle

5. Allan Lannon, Miller Academy History and Memories for the Millennium

2

‘An Edinburgh and Newnham girl’

Christina was born in 1889, the year of the Universities (Scotland) Act which would pave the way for the admission of women to Scottish universities from 1892. Thus, by the time she started school as a little girl in Thurso, a door had recently been opened through which she would gladly walk some years later.

Things were changing, but slowly. The traditional curriculum which educated girls for their assumed domestic role, be that as servants, as wives and mothers, or as ladies of leisure, persisted for a long time, excluding girls from entering university by denying them the required classical subjects. The financial commitment involved in supporting daughters towards and through university – particularly when many bursaries were only open to boys – also deterred some parents from encouraging their daughters into higher education. For although various professions now admitted single women, they remained firmly closed to married women. Why pay to educate a daughter who would not be able to pursue a career once she had married?

Christina was privileged to have supportive parents who encouraged her in her education and who had the financial resources to help her. Without these two factors it would have been hard if not impossible for her to achieve what she did. Many intelligent women of her generation were unable to pursue their dreams – equality was a long way off. But Peter and Katie not only approved of education, they actively encouraged it. One obituary to Peter Keith on his death in 1936 emphasised his passion for learning:

His chief outside interest may, however, be said to have been education, and for many years he was a leading member of the Thurso School Board, helping not a little to raise the prestige of higher education in the north of Scotland. … He had a firm belief in the value of education and his own family consisting of three sons and five daughters lived up to his belief.1

Christina began her schooling at the Miller Institute in Thurso, and her potential was quickly apparent. In 1903, aged 14, she was dux of the school, and it was around this time that her parents decided to send her south to continue her education, presumably with a view to qualifying her for university. She was sent firstly to St Leonard’s School in St Andrews, which opened in 1877 as the first girls’ school in Scotland run along English public school lines, and which offered a full curriculum. This was Christina’s first experience of living in an all-female institution, the type of environment in which she would spend much of her life, but she was unhappy. We cannot be sure why, but she may well have disliked the games which were an important part of school life at St Leonard’s – ‘I never am any good at running,’ she observed, after sprinting to catch the train in Amiens.

Christina left St Leonard’s and moved to a school in Edinburgh which had echoes of Miss Balmain’s establishment, her mother’s former school. Miss Williamson ran a boarding and day school in Abercromby Place, just a few streets away from the property which had housed Miss Balmain’s school. But a generation had passed since Katie came to school in Edinburgh, and those decades had been significant ones for women’s education. Miss Williamson’s school emphasised the opportunities available for women at university, offering ‘university-trained mistresses’ as well as visiting masters, and stating that pupils would be prepared for the required exams for Edinburgh University and for Girton and Newnham Colleges in Cambridge.2

The Keiths must have been satisfied with Miss Williamson’s school, which later became St Serf’s, for some of their younger daughters were also sent there. Christina sat the necessary preliminary examinations and entered Edinburgh University. She had by this time learned Latin, and announced her intention of studying for Honours in classics – despite not yet even knowing the Greek alphabet. So during her first year at university, alongside her other classes she learned the basics of Greek, and in her second year picked it up at university level, taking the class medal at the end of the year. The professor of Greek at the time was A.W. Mair, who was described by Christina’s brother Barrogill as ‘the brightest, dearest and most twinkling in all that glorious firmament’.3

During her time at the university, Christina lived in Masson Hall, the women’s hostel in George Square which had opened in 1897. It was named after David Masson, professor of rhetoric and English language, who had been an influential supporter of the campaign for women’s higher education and had provided lectures in English literature to the Edinburgh Ladies’ Education Association. The warden of the hostel was Frances Simson, who was herself one of the very first women to graduate from Edinburgh University and who was involved in an unsuccessful campaign all the way to the House of Lords to obtain the right for women graduates to vote for the University MP. Masson Hall not only provided accommodation for those women students who, like Christina, had come from further afield, it also offered a place of communal focus for all women students, who were able to meet there and use the facilities.

In 1920 Peter Keith had cause to write to The Scotsman about a dispute which was taking place within Masson Hall after the retirement of Frances Simson, and he expressed his satisfaction with the living arrangements of his daughters at Edinburgh University:

As the parent of one of the 33 young ladies presently in residence in Masson Hall, I am personally interested in the matter. Other members of my family have been in residence in that Hall for the last twelve years, almost without a break. It is gratifying to be able to say that, without exception during all that long period, while the late Warden was in charge, the young ladies in the Hall were most comfortable and happy. The discipline during her time was perfect, and there was never any trouble. Of course, in an institution of the kind it is absolutely essential that there must be proper discipline.4

That ‘proper discipline’ would have included strict regulations about meeting with men, particularly in private spaces. A way of life bound by regulations and conventions was one to which Christina would become accustomed and, as a tutor to young female students, one in which she later no doubt participated as a chaperone and figure of authority. It was in part the freedom from this ‘discipline’ which she found so exhilarating in Dieppe.

On 31 March 1910, Christina crossed the floor of the McEwan Hall, a small, slight figure, and was ‘capped’. Peter and Katie were probably watching among the assembled relatives and friends as their eldest daughter graduated with First Class Honours in Latin, Greek and classical archaeology – subjects which so recently had been considered a waste of time for a girl to learn. Of the ten others in her class graduating that day, nine were men. For her parents this was surely not only a moment of immense pride but the fruit of their own commitment to education which had reached back to the days when the doors of the university were firmly closed to women.

But for Christina this first degree was not the culmination of her education, but a stepping stone to further study. She had decided by this time to pursue a career in classical scholarship and academia, which was still a highly unusual path for a young woman to take. It is probably significant that at this point Christina took steps to continue her studies under the guidance of the two pioneering women in her chosen field, Eugénie Strong and Jane Ellen Harrison.

Along with another Edinburgh student Christina was awarded the Rhind Classical Scholarship, which was worth about £85 a year for two years. Before her graduation in March she also travelled down to Newnham College, Cambridge, and sat the exam for a separate Classical scholarship. She was successful, and was awarded an additional £50 a year for three years.5

Having secured this funding, Christina was set to return to Newnham in the autumn, but she had an adventure to undertake first. She left Edinburgh soon after her graduation, and early in April she arrived in Rome, where she would spend the next few months studying at the British School at Rome. This research institute had only recently been established, in 1901. Its assistant director was Eugénie Strong, an archaeologist and leading scholar of Roman art. The school’s Annual Report for 1910 records Christina’s time in Rome:

Miss Christina Keith, MA, University of Edinburgh, reached Rome early in April, and devoted herself to the study of sculpture. Towards the end of her time she began under Mrs Strong’s direction to specialise in Archaic Greek Sculpture. Miss Keith has recently gone to Newnham College, Cambridge, with a scholarship, but it is hoped that this promising young student may return to the School to resume her archaeological studies.

It seems Rome was just an interlude, an opportunity for twenty-one-year-old Christina to spend time living abroad and to develop her research interests. It speaks of her spirit of adventure and her readiness to welcome new experiences, an eagerness which would carry her to France and the army just eight years later, when the pleasant landscapes of Europe had become a vast field of death, grief and pain.

From Rome in October 1910 she returned to England and to Cambridge, where she would spend the next three years as a college scholar at Newnham. She excelled academically, just as she had done at Edinburgh, and was placed in the First Class in both parts of the Classical Tripos (Cambridge Honours examination). But there was one significant difference with Edinburgh. Neither Cambridge nor Oxford were yet prepared to award degrees to women. Christina was allowed to sit the exams, and was awarded a grade, but received at the time no formal qualification for her years of study at Cambridge. The awarding of degrees to women was fiercely and aggressively resisted, and was a topic of controversy during the time Christina was a student in Cambridge. The letter pages of The Times include many examples of strongly held opinions on both sides of the argument, including this letter from May 1913, written just as Christina was completing her Classical Tripos examinations to a level which would surpass many of her male contemporaries:

If the ladies of Girton, Newnham, Somerville and the rest of them want to stand on an equal footing with men, why on earth don’t they cut the painter with Oxford, Cambridge &c., link their colleges into an All-England Female University, and issue their own female degrees? The kind of parasitic prestige they are out for at present involves a humiliating confession of sexual inferiority.6

The unequal status of men and women at Cambridge created an atmosphere very different from the one Christina had known in Edinburgh. Because the battle was still to be won, female students knew that any apparent failure on their part, be it academic or moral, could damage their cause.7 Strict regulations governed the conduct of female students. Chaperones were often required to accompany them to lectures. Walking in the street with a man was forbidden – which was sometimes awkward when moving together from one class to another. A woman could only entertain a brother or a father in her room, and in those circumstances her friends would not be allowed to be present. Propriety was everything.

There is no suggestion that Christina was inclined to rebel against these rules; rather, it was because she was so accustomed to a life in which the rules of respectability were understood by all that her six months in France involved such a sense of transformation. A natural and gifted student, she relished all that Cambridge had to offer her academically without, at that time, apparently being frustrated by its conventions. One outstanding figure from whom Christina could learn was another pioneering academic, Jane Harrison. Like Eugénie Strong, Jane Harrison’s unconventional life demonstrated to her students that it might be difficult to be a successful female classical scholar but it was not impossible.

Jane Harrison had held a research fellowship at Newnham since 1898. She taught students in Part II of the Classical Tripos who were specialising in her own research interests of art and archaeology. She almost certainly taught Christina. She was an unconventional and inspirational teacher, whose methods were perhaps best suited to the most gifted students. Her second significant publication on Greek religion was published during Christina’s time at Newnham, and her work has since been highly influential. At a time when academic women were under great scrutiny Harrison became a controversial figure, and was criticised not only because of her feminist approach to her work but also as a pacifist and an atheist. Harrison formed a very close friendship with a student, Hope Mirrlees, who would have been well known to Christina as they arrived at Newnham in the same year, although Hope never completed the Tripos.8

Christina left Newnham, and took the next step in her own career as a professional female academic by applying for the vacant post of lecturer in classics at Armstrong College, Newcastle, which was part of the University of Durham. She and four other candidates were interviewed on 16 June 1914 by Professor John Wight Duff, who recorded in his diary, ‘My new assistant to succeed my “second-in-command” is an Edinburgh and Newnham girl.’9

Professor Duff spent some time that day explaining to her what her duties would be when she took up her position in October. Perhaps he showed her round the college itself with its grand buildings, parts of which were newly completed, and took her into the college library. A few months later, Christina believed, she would be walking these corridors and lecturing in these halls.

But Christina would never teach in the buildings she saw that day, and would never use the college library. By the time she returned to take up her post in October 1914, war had broken out and everything had changed.

Notes

1. The Scotsman, 19 December 1936

2. Advertisements in various editions of The Scotsman, 1903–08

3. David Barrogill Keith, ‘Bygone Days at Edinburgh University’ in University of Edinburgh Journal, spring 1965

4. The Scotsman, 30 June 1920

5. The Scotsman, 1 April 1910; The Times, 6 August 1910

6. The Times, 23 May 1913

7. See, for example, anecdotes in (ed.) Ann Philips, A Newnham Anthology, 1979

8. Annabel Robinson, The Life and Work of Jane Ellen Harrison, 2002, and Hugh Lloyd-Jones, ‘Jane Ellen Harrison’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

9. Diaries of John Wight Duff in Newcastle University Archives

3

‘How fine their sense of duty has been’

In October 1914, when Christina came to Newcastle to take up her first post as a lecturer, her brother Barrogill had already enlisted in the army and was at a training camp in Nigg in the north of Scotland. Young men from Armstrong College whom she would have otherwise taught had similarly left their studies to become part of the British Expeditionary Force. The college buildings had been requisitioned and turned into a military hospital, and would not be returned to the university until the war was over, by which time Christina had moved on.