9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

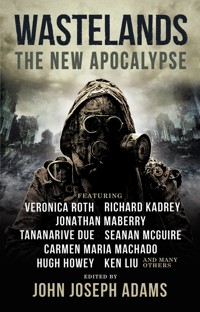

The brilliant new post-apocalyptic collection by master anthologist John Joseph Adams, for the first time including new stories by the edgiest modern writers. The new post-apocalyptic collection by master anthologist John Joseph Adams, featuring never-before-published stories and curated reprints by some of the genre's most popular and critically-acclaimed authors. In WASTELANDS: THE NEW APOCALYPSE, veteran anthology editor John Joseph Adams is once again our guide through the wastelands using his genre and editorial expertise to curate his finest collection of post-apocalyptic short fiction yet. Whether the end comes via nuclear war, pandemic, climate change, or cosmological disaster, these stories explore the extraordinary trials and tribulations of those who survive. Featuring never-before-published tales by: Veronica Roth, Hugh Howey, Jonathan Maberry, Seanan McGuire, Tananarive Due, Richard Kadrey, Scott Sigler, Elizabeth Bear, Tobias S. Buckell, Meg Elison, Greg van Eekhout, Wendy N. Wagner, Jeremiah Tolbert, and Violet Allen—plus, recent reprints by: Carmen Maria Machado, Carrie Vaughn, Ken Liu, Paolo Bacigalupi, Kami Garcia, Charlie Jane Anders, Catherynne M. Valente, Jack Skillingstead, Sofia Samatar, Maureen F. McHugh, Nisi Shawl, Adam-Troy Castro, Dale Bailey, Susan Jane Bigelow, Corinne Duyvis, Shaenon K. Garrity, Nicole Kornher-Stace, Darcie Little Badger, Timothy Mudie, and Emma Osborne. Continuing in the tradition of WASTELANDS: STORIES OF THE APOCALYPSE, these 34 stories ask: What would life be like after the end of the world as we know it?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also edited by John Joseph Adams

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

John Joseph Adams

Bullet Point

Elizabeth Bear

The Red Thread

Sofia Samatar

Expedition 83

Wendy N. Wagner

The Last to Matter

Adam-Troy Castro

Not this War, Not this World

Jonathan Maberry

Where Would You Be Now

Carrie Vaughn

The Elephants’ Crematorium

Timothy Mudie

Bones of Gossamer

Hugh Howey

As Good As New

Charlie Jane Anders

One Day Only

Tananarive Due

Black, Their Regalia

Darcie Little Badger

The Plague

Ken Liu

Four Kittens

Jeremiah Tolbert

The Eyes of the Flood

Susan Jane Bigelow

The Last Garden

Jack Skillingstead

Through Sparks in Morning’s Dawn

Tobias S. Buckell

Cannibal Acts

Maureen F. McHugh

Echo

Veronica Roth

Shooting the Apocalypse

Paolo Bacigalupi

The Hungry Earth

Carmen Maria Machado

Last Chance

Nicole Kornher-Stace

A Series of Images from a Ruined City at the End of the World

Violet Allen

Come On Down

Meg Elison

Don’t Pack Hope

Emma Osborne

Polly Wanna Cracker?

Greg van Eekhout

Otherwise

Nisi Shawl

And the Rest of Us Wait

Corinne Duyvis

The Last Child

Scott Sigler

So Sharp, So Bright, So Final

Seanan McGuire

Burn 3

Kami Garcia

Snow

Dale Bailey

The Air Is Chalk

Richard Kadrey

The Future Is Blue

Catherynne M. Valente

Francisca Montoya’s Almanac of Things that Can Kill You

Shaenon K. Garrity

Acknowledgments

About the Editor

Also Available from Titan Books

Also edited by John Joseph Adams

The Apocalypse Triptych, Vol. 1: The End is Nigh (with Hugh Howey)

The Apocalypse Triptych, Vol. 2: The End is Now (with Hugh Howey)

The Apocalypse Triptych, Vol. 3: The End Has Come (with Hugh Howey) Armored

Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2015 (with Joe Hill)

Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2016 (with Karen Joy Fowler)

Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2017 (with Charles Yu)

Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2018 (with N.K. Jemisin)

Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2019 (with CarmenMaria Machado) [Forthcoming, Oct. 2019]

Brave New Worlds

By Blood We Live

Cosmic Powers

Dead Man’s Hand*

The Dystopia Triptych, Vol. 1: Ignorance is Strength (with Hugh Howey) [Forthcoming 2020]

The Dystopia Triptych, Vol. 2: Burn the Ashes (with Hugh Howey) [Forthcoming 2020]

The Dystopia Triptych, Vol. 3: Or Else the Light (with Hugh Howey) [Forthcoming 2020]

Epic: Legends of Fantasy

Federations

The Improbable Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

HELP FUND MY ROBOT ARMY!!! and Other Improbable Crowdfunding Projects

Lightspeed Magazine

Lightspeed: Year One

The Living Dead

The Living Dead 2

Loosed Upon the World

The Mad Scientist’s Guide To World Domination

Nightmare Magazine

Operation Arcana

Other Worlds Than These

Oz Reimagined (with Douglas Cohen)

A People’s Future of the United States (with Victor LaValle)

Press Start to Play (with Daniel H. Wilson)

Robot Uprisings (with Daniel H. Wilson)

Seeds of Change

Under the Moons of Mars

Wastelands*

Wastelands 2*

The Way of the Wizard

What the #@&% is That? (with Douglas Cohen)

* From Titan Books

EDITED BY

JOHN JOSEPH ADAMS

TITAN BOOKS

WASTELANDS: A NEW APOCALYPSE

Print edition ISBN: 9781785658952E-book edition ISBN: 9781785658969

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UPwww.titanbooks.com

First Titan Books edition: June 20192 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Compilation and “Introduction” by John Joseph Adams. © 2019 by John Joseph Adams. Introduction appears for the first time in this volume.

“A Series of Images from a Ruined City at the End of the World” by Violet Allen. © 2019 by Violet Allen. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“As Good as New” by Charlie Jane Anders. © 2014 by Charlie Jane Anders. Originally published in Tor.com. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Shooting the Apocalypse” by Paolo Bacigalupi. © 2014 by Paolo Bacigalupi. Originally published in The End is Nigh. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Black, Their Regalia” by Darcie Little Badger. © 2016 by Darcie Little Badger. Originally published in Fantasy Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Snow” by Dale Bailey. © 2015 by Dale Bailey. Originally published in Nightmare Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Bullet Point” by Elizabeth Bear. © 2019 by Elizabeth Bear. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“The Eyes of the Flood” by Susan Jane Bigelow. © 2018 by Susan Jane Bigelow. Originally published in Lightspeed Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Through Sparks in Morning’s Dawn” by Tobias S. Buckell. © 2019 by Tobias S. Buckell. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“The Last to Matter” by Adam-Troy Castro. © 2018 by Adam-Troy Castro. Originally published in Lightspeed Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“One Day Only” by Tananarive Due. © 2019 by Tananarive Due. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“And the Rest of Us Wait” by Corinne Duyvis. © 2016 by Corinne Duyvis. Originally published in Defying Doomsday. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Come on Down” by Meg Elison. © 2019 by Meg Elison. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“Burn 3” by Kami Garcia. © 2013 by Kami Garcia. Originally published in Shards & Ashes. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Francisca Montoya’s Almanac of Things That Can Kill You” by Shaenon K. Garrity. © 2014 by Shaenon K. Garrity. Originally published in Lightspeed Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Bones of Gossamer” by Hugh Howey. © 2019 by Hugh Howey. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“The Air is Chalk” by Richard Kadrey. © 2019 by Richard Kadrey. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“Last Chance” by Nicole Kornher-Stace. © 2017 by Nicole Kornher-Stace. Originally published in Clarkesworld Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Plague” by Ken Liu. © 2013 by Ken Liu. Originally published in Nature Futures. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Hungry Earth” by Carmen Maria Machado. © 2013 by Carmen Maria Machado. Originally published in Mothership: Tales from Afrofuturism and Beyond. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Not this War, Not this World” by Jonathan Maberry. © 2019 by Jonathan Maberry. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“So Sharp, So Bright, So Final” by Seanan McGuire. © 2019 by Seanan McGuire. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“Cannibal Acts” by Maureen F. McHugh. © 2017 by Maureen F. McHugh. Originally published in Boston Review: Global Dystopias. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Elephants’ Crematorium” by Timothy Mudie. © 2018 by Timothy Mudie. Originally published in Lightspeed Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Don’t Pack Hope” by Emma Osborne. © 2018 by Emma Osborne. Originally published in Nightmare Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Echo” by Veronica Roth. © 2019 by Veronica Roth. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“The Red Thread” by Sofia Samatar. © 2016 by Sofia Samatar. Originally published in Lightspeed Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Otherwise” by Nisi Shawl. © 2012 by Nisi Shawl. Originally published in Brave New Love. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Last Child” by Scott Sigler. © 2019 by Scott Sigler. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“The Last Garden” by Jack Skillingstead. © 2017 by Jack Skillingstead. Originally published in Lightspeed Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Four Kittens” by Jeremiah Tolbert. © 2019 by Jeremiah Tolbert. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“The Future is Blue” by Catherynne M. Valente. © 2016 by Cat Valente. Originally published in Drowned Worlds. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Polly Wanna Cracker?” by Greg van Eekhout. © 2019 by Greg van Eekhout. Appears for the first time in this volume.

“Where Would You Be Now” by Carrie Vaughn. © 2018 by Carrie Vaughn. Originally published in Tor.com. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Expedition 83” by Wendy N. Wagner. © 2019 by Wendy N. Wagner. Appears for the first time in this volume.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

INTRODUCTION

JOHN JOSEPH ADAMS

As I write this, it’s Thanksgiving. A lot of us, including me, have a lot of things to be thankful for. Yet by any reasonable assessment, the world as a whole today seems closer to the precipice of apocalypse than perhaps it has ever been. The Doomsday Clock—maintained by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists—shows that we are at two minutes to midnight… which means we’re the closest we’ve been to “doomsday” since 1953.

But if you pay attention to the news at all, you don’t need the Doomsday Clock to tell you that. While it is tempting to leave aside—as the subject matter for an introduction to a different anthology—the dystopian elements of today’s world (which are legion), the slow but alarmingly frequent collapse of democracies around the world, coupled with the rise of authoritarian regimes and divisive, hateful rhetoric, makes World War III look like an increasingly frightening—and disturbingly probable—outcome.

Of course, destroying ourselves with weapons of war is just one of many possible apocalyptic scenarios that could come to pass. Climate change looms over everything as an omnipresent and terrifying threat to the entire world. I’m witnessing it up close and personal as I write this from my home in California, where there are raging wildfires burning to both the north and south of me—thankfully far enough away that my family is in no danger. Not everyone was so lucky… including the residents of the town called Paradise (which now is anything but). Yet we still have people—including prominent world leaders—denying anthropogenic influence and moving too slowly to try to arrest the progress of climate change. As I’ve said in the introduction to my climate fiction anthology Loosed Upon the World, “Welcome to the end of the world, already in progress.”

There are many other ways the world might end. A huge extraterrestrial object slamming into the Earth might cause an extinction-level event. Hell, a huge extraterrestrial race might do the same. Neither of these seem terribly likely, though if I were the kind of ghoul who’d bet on how the world will end, I’d put way more money on one than the other.

Or there’s always the chance that a horrible pandemic will wipe us out, leaving behind a world devoid of people, and nothing but the edifices of civilization as monuments to what we achieved as sentient creatures. Or—getting back to anthropogenic apocalypses for a moment—there’s always the chance some rogue nation will engineer a biological weapon to wipe out a specific population, thereby dooming the entire world by mistake. Or, hey, maybe we’ll try to do something good with viruses, like releasing some kind of engineered microbe into the atmosphere—perhaps designed to combat climate change. Then everything goes awry, and actively, literally kills us.

My point being: We’re almost certainly and in all conceivable ways fucked six ways to Sunday.

Despite that, it somehow still remains entertaining to imagine being one of the survivors, to be one of the ones “scrounging for cans of pork and beans”* and maybe even finding yourself with the responsibility of trying to build a new world from the ashes of the old.

So once again, I’ve delved into the vault† and gathered more “memorabilia”‡ of the apocalypse… all for your reading “pleasure.” The selections you’ll find here all come from the last several years—thirty-four stories total, including twenty reprints and fourteen never-before-published tales.

I can only hope you’ll get to read them before the end actually comes…

* After John Varley, from “The Manhattan Phone Book, Abridged”.

† After Fallout, but with the small “v” to stay grammatically correct in this particular context.

‡ After Walter M. Miller, Jr., in A Canticle for Leibowitz.

BULLET POINT

ELIZABETH BEAR

Elizabeth Bear was born on the same day as Frodo and Bilbo Baggins, but in a different year. She is the Hugo, Sturgeon, Locus, and Campbell Award winning author of thirty novels and more than a hundred short stories, and her hobbies of rock climbing, archery, kayaking, and horseback riding have led more than one person to accuse her of prepping for a portal fantasy adventure. She lives in Massachusetts with her husband, writer Scott Lynch.

It takes a long time for the light to die. The power plants can run for a while on automation. Hospitals have emergency generators with massive tanks of fuel. Some houses and businesses have solar panels or windmills. Those may keep making juice, at least intermittently, until entropy claims the workings.

How long is it likely to take then? Six months? The better part of a decade?

I stand on the roof deck of the Luxor casino parking garage, watching the lights that remain, and I wonder. I don’t even know enough to theorize, really.

I’m not an engineer. I used to be a blackjack dealer.

Now I am the only living human left on Earth.

It’s not all bad. I don’t have to deal with:

• Death (except the possibility of my own, eventually).

• Taxes.

• Annoying holidays with my former extended family.

• Airplane lights crossing the desert sky.

• Chemtrails (okay, those were never real in the first place).

• Card counters.

• Maisie the pit boss. Thank God.

• My ex-husband. Double thank God.

Well, of course I can’t know for sure that I’m the only living person. But for all practical purposes, I seem to be. Maybe Las Vegas is the only place that got wiped out. Maybe over the mountain, Pahrump is thriving.

I don’t think so. I hear the abandoned dog packs howling in the night, and I’ve watched the lights go out, one by one by one.

I feel so bad for those dogs. And even worse for all the ones trapped in houses when the end came. All the cats, guinea pigs, pet turtles. The horses and burros, at least, have a chance. Wild horses can survive in Nevada.

There are so many of them. There’s nothing I can do.

If there are any other humans surviving, they are far away from here, and I have no idea where to find them, or even how to begin looking. I have to get out of the desert, though, if I want to keep living. For oh, so many reasons.

I can trust myself, at least. Trusting anybody else never got me where I wanted to be.

Another thing I don’t know for sure, and can’t even guess at: Why.

Not knowing why?

That’s the real pisser.

* * *

Here is an incomplete list of things that do not exist anymore:

• Fresh-baked cookies (unless I find a propane oven and milk a cow and churn some butter and then bake them).

• Jesus freaks (I wonder how they felt when the Rapture happened and it turned out God was taking almost literally everybody? That had to be a little bit of a come-down).

• Domestic violence.

• Did I mention my ex-husband?

There’s more than enough Twinkies just in the Las Vegas metro area to keep me in snack cakes until the saturated fat kills me. If I last long enough that that’s what gets me, I might even find out if they eventually go stale.

* * *

A problem with being in Las Vegas is getting back out of it again. Walking across a desert will kill me faster than snack cakes. And the highway is impassable with all the stopped and empty cars.

Maybe I can find a monster truck and drive it over everything.

More things that don’t exist anymore:

• Reckless driving.

• Speeding tickets.

• Points on your license.

• Worrying about fuel efficiency.

Las Vegas Boulevard is dark and still. Nevertheless, I can’t make myself walk on the blacktop, even though the cars there are unmoving, bumper to bumper for all eternity. The Strip’s last traffic jam.

There might be bodies in the cars. I don’t look.

I don’t want to know.

I don’t think there’s going to be anybody alive, but that might be worse. More dangerous, anyway.

I mean, I think I’m the last. But I don’t know.

That was also the reason I couldn’t make myself walk along the sidewalk. It was too exposed. The tall casinos were mostly designed so that their windows had views of something more interesting than hordes of pedestrians—hordes of pedestrians now long gone—but somebody might be up there, and somebody up there might spot me. A lone moving dot on a sea of silent asphalt.

Lord, where have all the people gone?

So I stick to the median. With its crape myrtle hedges and doomed palm trees already drooping in the failed irrigation to break up my outline. With the now pointless crowd control barriers to discourage jaywalkers from darting into traffic.

Two more things:

• Traffic.

• Jaywalkers.

Hey, and one more:

• Assholes.

I am half hoping to find people. And I am 90% terrified of what they might do if I find them. Or if they find me first.

I’m pretty sure this wasn’t actually the Rapture.

Pretty sure.

I keep trying to tell myself that there’s not a single damned person from the old world that I really miss. That it’s time I had some time alone, as the song used to go. It is nice not to be on anybody else’s schedule, or subject to anybody else’s expectations or demands. At least my ex-husband is almost certainly among the evaporated. That’s a load off my mind.

I moved to Vegas, changed my name by sealed court order, abandoned a career I worked for ten years to get, and became a casino dealer in order to hide from him. Considering that, it’s not a surprise to find myself relieved that whatever ends up causing me to look over my shoulder from now on, it won’t be Paul.

I got the cozy apocalypse that was supposed to be the best-case-apocalypse-scenario—wish fulfillment—complete with the feral dogs that howl in the night.

But it doesn’t feel like wish fulfillment. It feels like… being alone on the beach in winter. I’m lonely, and I miss… well, I already left behind everybody I loved. But leaving somebody behind is not the same thing as knowing they are gone.

There’s potential space, and there’s empty space.

Maybe that’s why I’m still here. Nobody thought to tap me on the shoulder and say, “Hey, Izzy, let’s go,” because I’d already abandoned all of them to save my own life one time.

Hah. There I go again. Making things about me that aren’t.

I thought I was used to being lonely, but this is a whole new level of alone. I feel like I should be paralyzed by survivor guilt. But I am a rock. I am an island.

• Simon

• Garfunkel

Lying to yourself is, however, still alive and well.

* * *

The gun is heavy. Cold, blue metal. It feels about twice its size.

I find it under the seat of a cop car with the driver’s door left open. The keys are in the ignition. The dome light has long since burned out, and the open-door dinger has dinged itself into silence.

It’s a handgun. A revolver. Old School. There is a holster to go with it, but no gunbelt. There are six bullets in the cylinder.

• The Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department.

• Crooked cops.

• Throwaway guns.

I unbuckle my belt, thread it through the loops on the holster, and hang it at my hip.

There are plenty of rattlesnakes, still.

• Antivenin.

• Emergency rooms.

There are plenty of antibiotics. And pain medication. And canned peaches.

And a nice ten-speed mountain bike that I liberate from a sporting goods place, along with one of those trailers designed for pulling your kid or dog along. I’ve never been much of an urban biker, preferring trails, but it wasn’t like I would have to contend with traffic. And it seems like the right tool for weaving in and out of rows of abandoned cars.

I pick up a book on bike repair too, and some tire patches and spare tubes and so on. Plus saddlebags and baskets. And a lot of water bottles.

It turns out that one thing the zombie apocalypse movies got really wrong was the abundance of stockpiled resources available after a population of more than seven billion people just… ceases to exist.

There’s plenty of stuff to go around when there’s no “around” for it to go. Until the stuff goes bad, anyway.

That’s the reason I want to get out of the desert before summer comes. Things will last longer in colder places, with less murderous UV.

* * *

Things that apparently do still exist: at least one other human being.

And he is following me.

He picks me up at a Von’s. I’m in the pasta aisle. The rats have started gnawing into boxes, but the canned goods are relatively fine. And if you can ignore the silence of the gaming machines and the smell of fermenting fruit, rotten meat, and rodent urine, it’s not that different than if I were shopping at 2 am in the old world.

I’m crouched down, filling my backpack with Beefaroni and D batteries from the endcap, when I hear footsteps. It’s daylight outside, but it’s dark inside the store. I turn off my LED flashlight. My heart contracts inside me, shuddering jolts of blood through my arteries. The rush and thump fills my ears. I strain through them for the sounds that mean life or death: the scrape or squeak of boot sole on tile, the rattle of packages.

My hands shake as I zip the backpack inch by silent inch. I stand. The straps creak. I can’t be sure if I have managed not to tremble the bag into a betraying clink. One step, then another. Sideways, slipping, setting each foot down carefully so it doesn’t make a sound.

As I get closer to the front of the store (good) the ambiance grows brighter (bad). I hunker by the side of a dead slot machine, shivering. From where I crouch, I can peek around and see a clear path to the door.

The whole way is silhouetted against the plate glass windows. The pack weighs on my shoulders. If I leave it, I’m not really leaving anything. I can get another, and all the Chef Boyardee I want. But it’s hard to abandon resources.

And hey, the cans might stop a bullet.

Don’t hyperventilate.

Easier said than done.

Sliding doors stopped working when the store lights did. Too late, I realize there’s probably a fire door in the back I could have slipped out of more easily. In the old world, that would have been alarmed… but would the alarm even work anymore?

There is a panic bar on the front doors. I crane over my shoulder, straining for motion, color, any sign of the person I am certain I heard.

Nothing.

Maybe I’m hallucinating.

Maybe he’s gone to the back of the store.

I nerve myself and hit the door running. I got it open on the way in, so I know it isn’t locked. It flies away from the crash bar—no subtlety there—and I plunge through, sneakers slapping the pavement. The parking lot outside is flat and baking, even in September. The sun hits my ballcap like a slap. Rose bushes and trees scattered in the islands are already dead from lack of water. The rosemary bushes and crape myrtles look a little sad, but they are holding on.

I sprint toward them. Now the pack makes noise, the cans within clanking and thumping on each other—and clanking and thumping against my ribs and spine. I’ll have a suite of bruises because of them. But I left my bike on the kickstand in the fire lane, and—wonder of wonders—it’s still there. I throw myself at it and swing a leg through, pushing off with my feet before I ever touch the pedals. I miss my first push and skin the back of my calf bloody on the serrated grip.

I curse, not loud but on that hiss of breath you get with shock and pain. The second time, I manage to get my heel on the pedal. The bike jerks forward with each hard pump.

I squirt between parked cars. As my heart slows, I let myself think I’ve imagined the whole thing. Until the supermarket doors crash open, and a male voice shrill with desperation yells, “Miss! Come back! Miss! Don’t run away from me! Please! I’m not going to hurt you!”

And maybe he’s not. But I’m not inclined to trust. Trusting never did get me anywhere I wanted to be.

I push down and pedal harder. I don’t coast.

He only shouts after me. He doesn’t shoot. And I don’t look back.

* * *

Now that he knows I exist, he’s not going to stop looking.

I know this the way I know my childhood street address.

And why would he stop? People need people, or so we’re always told. Being alone—really alone, completely alone—is a form of torture.

To be utterly truthful, there’s a part of me that wants to go looking for him. Part of me that doesn’t want to be alone anymore either.

The question I have to ask myself is whether that lonely part of me is stronger than the feral, sensible part that cautions me to run away. To run, and keep running.

Because it’s the apocalypse. And I’m not very big, or a trained fighter. And because of another thing that doesn’t exist anymore:

• Social controls.

Dissociation, though—that I’ve got plenty of.

* * *

He is going to come looking for me. Because of course he will. I hear him calling after me for a long time as I ride away. And I know he tries to follow me because I follow him.

We’re the last two people on Earth and how do you get more Meet Cute than that? We’ve all stayed up late watching B movies in the nosebleed section of the cable channels and we’ve all read TV Tropes and we all know how this story goes.

But my name isn’t Eve. It’s Isabella. And I have an allergy to clichés.

• Dating websites.

• Restraining orders.

• Twitter block lists.

• Domestic violence shelters.

I stalk him. I’ll call it what it is.

It’s easy to find him again: he’s so confident and fearless that he’s still wandering around in the same neighborhood trying to get my attention.

I mean, first I go back to my current lair and get ready to run.

I load up the bike trailer with my food and gear, and flats and flats and flats of water. My sun layers and my hat go inside and I zip the whole thing up.

Then I hide it, and I check again to be sure my gun is loaded.

And then I go and stalk him.

* * *

He’s definitely a lot bigger than me. But he doesn’t look a damned thing like my ex, which is a point in his favor.

And he isn’t trying in the least to be sneaky. He’s just walking down the sidewalk, swerving to miss the cars that rolled off the road when their drivers disappeared, pulling a kid’s little red wagon loaded with supplies. He’s armed with a pistol on his belt, but so am I. And at least he’s not strung all over with bandoliers and automatic weapons. Plus, there are enough of those hungry, terrified feral dog packs around that a weapon isn’t a bad idea.

I wonder how long it will be before the cougars move back down from the mountains and start eating them all.

The circle of life.

Poor dogs.

They were counting on us, and look where that got them.

* * *

The only other living human being (presumed) is wearing a dirty T-shirt (athletic gray), faded jeans, and a pair of high-top skull-pattern Chucks that I appreciate the irony of, even while knowing his feet must be roasting in them. I make him out to be about twenty-five. His hair is still pretty clean cut under his mesh-sided brimmed hat, but he’s wearing about two weeks of untrimmed beard. Two weeks is about how long it’s been since the world ended.

He calls out as he walks along. How can anyone be so unafraid to attract attention? So confident of taking up all that space in the world? Like he thinks he has a right to exist and nobody is going to come take it away from him.

He’s so relaxed. It scares me just watching him.

I do notice that he doesn’t seem threatening. There’s nothing sinister, calculated, or menacing about this guy. He keeps pushing his hat up to mop the sweat from under it with an old cotton bandanna. He doesn’t have a lot of situational awareness, either. Even with me orbiting him a couple of blocks off on the mountain bike, he doesn’t seem to notice me watching. I’m staying under cover, sure. But the bike isn’t silent. It has a chain and wheels and joints. It creaks and rattles and whizzes a little, like any bicycle.

Blood has dried, itchy and tight-feeling, on the back of my calf. The edge of my sock is stiff. I drink some of the water in my bottle, though not as much as I want to.

It’s getting on toward evening and he’s walking more directly now, in less of a searching wander, when I make up my mind. He seems to be taking a break from searching for me, at least for the time being. He’s stopped making forays into side streets, and he’s stopped calling out.

I cycle hard on a parallel street to get in front of him, and from a block away I show myself.

He stops in his tracks. His hands move away from his sides and he drops the little red wagon handle. My right hand stays on the butt of my holstered gun with the six bullets in it.

“Hi,” he says, after an awkward pause. He pitches his voice to carry. “I’m Ben.”

“Hi,” I call back. “I’m Isabella.”

“You came back.”

I nod. Never in my memory—probably in living memory—has it been quiet enough in this city that you could hear somebody clearly if they called to you from this far away. But it’s that quiet now. Honey bees buzz on the crape myrtles. I wonder if they’re Africanized.

“Nice bike, Isabella.”

“Thanks.” I let the smirk happen. “It’s new.”

He laughs. Then he bends down and picks up the handle of his little red wagon. When he straightens, he lets his hands hang naturally. “Have you seen anybody else?”

I shake my head.

“Me neither.” He makes a face. “Mind if I come over?”

My heart speeds. But it’s respectful that he’s asking, right?

I don’t get off the bike or walk it toward him. I cant it against one cocked leg and wait.

“Sure.” I try to sound confident. I square my shoulders.

You know what else doesn’t exist anymore?

• Backup.

We head off side by side. I’ve finally gotten off the bike and am walking it, though I casually keep it and the wagon in between us and stay out of grabbing range. The step-through frame will help me hop on and bug out fast if I need to.

Ben offers me a granola bar. I guess he learned early on, as I did, that once the power went off, there wasn’t any point in harvesting chocolate. Well, I mean, it’s still calorie-dense. But if it’s daytime, it’s probably squeezable. And if it’s not melted, it has re-solidified into the wrapper and you’ll wind up eating a fair amount of plastic.

“Terrorists,” he hazards, with the air of one making conversation.

I shake my head. “Aliens.”

He thinks about it.

“We probably had it coming,” I posit.

“I don’t think it’s a great idea to stay in Vegas,” Ben says, with no acknowledgment of the non sequitur.

“I’ve been thinking that too.”

He glances sidelong at me. His face brightens. “I was thinking of heading to San Diego. Nice and temperate. Lots of seafood. Easy to grow fruit. Not as hot as here.”

I think about earthquakes and drought and wildfires. My plan was the Pacific Northwest, where the climate is mild and wet and un-irrigated agriculture could flourish. I figure I’ve got maybe five years to figure out a sustainable lifestyle.

And I don’t want to spend the rest of my life living off ceviche. Or dodging wildfires and worrying about potable water.

I don’t say anything, though. If I decide to split on this guy, it’s just as well if he doesn’t know what my plans were. Especially if we’re the last two people on Earth.

Why him? Why me?

Who knows.

“Lot of avocados down there.” I can sound like I’m agreeing to nearly anything.

He nods companionably. “The bike is a good idea.”

“I’d be a little scared to try cycling across the mountains and through Baker. That’s some nasty desert.”

Mild pushback, to see what happens in response.

“I figure you could make it in a week or ten days.”

That would be some Tour de France shit, Ben. Especially towing water. But I don’t say that.

• Tour de France.

“Or,” he says, “I thought of maybe a Humvee. Soon, while the gas is still good.”

He loses a few points on that. I wouldn’t feel bad at all about bullet pointing Hummers, and I don’t feel nearly as bad about bullet pointing the sort of people who used to drive them as I probably ought to.

“Look,” Ben says, when I’ve been quiet for a while, “why don’t we find someplace to hole up? It’s getting dark, and the dog packs will be out soon.”

I look at him and can’t think what to say.

He sighs tolerantly, not getting it. I guess not getting it isn’t over yet either.

“I give you my word of honor that I will be a total gentleman.”

* * *

You have to trust somebody sometime.

I go home with Ben. Not in the euphemistic sense. In the sense that we pick a random house and break into it together. It has barred security doors and breaking in would be harder, except the yard wasn’t xeriscaped and all the

• Landscaping

is down to brown sticks and sadness. Which makes it super easy to spot the fake rock that had once been concealed in a now-desiccated foundation planting, turn it over, and extract the key hidden inside.

We let ourselves in. There used to be a security system, but it’s out of juice. The house is hot and dark inside, and smells like decay. Plant decay, mostly: sweetish and overripe, due to the fruit rotting in bowls on the counter. Neither Ben nor I is dumb enough to open the refrigerator. We do check the bedrooms for bodies. There aren’t any—there never are—but we find the remains of a hamster that starved and had mummified in its cedar chips.

That makes me sad, like the dog packs. If this is the Rapture, I hope God gets a nasty call from the Afterlife Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

We find can openers and plates and set about rustling up some supper. All the biking has made us ravenous, and when I finish eating, I am surprised to discover that I have let my guard down. And that nothing terrible has happened.

Ben looks at me across the drift of SPAM cans and Green Giant vacuum-pack corn (my favorite). “This would be perfect if the air conditioning worked.”

“Sometimes you can find a place with solar panels,” I say noncommittally.

“Funny that all that tree hugging turned out useful after all, isn’t it?” And maybe he sees the look on my face, because he raises a hand, placating. “Some of my best friends are tree huggers!” He looks down, mouth twisting. “Were tree huggers.”

So I forgive him. “My plan had been to find someplace that was convenient and had solar, and if I was lucky its own well. And wait for winter before I set out.”

“That’s a good idea.” He picks at a canned peach.

“Also, the older houses up in Northtown and on the west side of the valley. Those handle the heat better.”

“Little dark up there in North Vegas,” Ben says, casually. “I mean, not that there’s anybody left, but it was.”

I open my mouth. I close it. I almost hear the record scratch.

I’d have thought it was safe to bullet

• Racism.

But I guess not.

* * *

I don’t say, So it’s full of evaporated black people cooties? I get up, instead, and start clearing empty tin cans off the table and setting them in the useless sink. Ben watches me, amused that I’m tidying this place we’re only going to abandon.

Setting things to rights, the only way I can.

He’s relaxed and expansive now. A little proprietary.

I am not quite as scared as I ever have been in my life. But that’s only because I’ve been really, really scared.

“It’s just us now. You don’t have anybody to impress,” Ben says. “You’re free. You don’t have to play those games to get ahead.”

I blink at him. “Games?”

He stands up. I turn toward the sink. Knives in the knife block beside it. If it comes down to it, they might be worth a try. I try to keep my eyes forward, to not give him a reason to think I’m being impertinent. But I keep glancing back.

I look scared. And that’s bad. You never want to look scared.

It attracts predators.

“Nobody can hurt you for saying the truth now. And obviously,” he says with something he probably means to be taken as a coaxing smile, “it’s up to us to repopulate the planet.”

“With white people.” It just comes out. I’ve never been the best at self-censorship. Even when I know speaking might get me hurt.

At least I keep my tone neutral. I think.

Neutral enough, I guess, because he leers again. “Maybe God’s given us a second chance to get it right, is all I’m saying. Don’t you think it’s a sign? I mean, here I meet the last woman on earth, and she’s a blue-eyed blonde.”

The little tins fit inside the big tins. The spoons stack up.

• Ice cream.

Though I could probably make some, if I found that cow. And snow. And bottle blondes are still going to be around until my hair grows out. I don’t have any reason to try to change my appearance now.

Ben moves, the floor creaking under him. “If you’re not going to try to save humanity, what’s the point in even being alive? Are you going to just give up?”

I turn toward him. I put my back toward the sink. I half-expect him to be looming over me but he’s standing well back, respectfully. “Maybe humanity has a lifespan, like everything else. You’re going to die eventually.”

“Sure,” he says. “That’s why people have kids. To leave a legacy. Leave something of themselves behind.”

“Two human beings are not a viable gene pool.”

“You don’t want to rush into anything,” he says. “That’s all right. I can respect that.”

And then he does something that stuns me utterly. He goes and lies down on the sofa. He only glances back at me once. The expression on his face is trying to be neutral, but I can see the smugness beneath it.

The fucking confidence.

Of course he doesn’t need to push his luck, or my timeline. Of course he’s confident I’ll come around. He’s got all the time in the world.

And what choice have I got in the long run, really?

* * *

There will always be assholes.

I leave that house in the morning at first light. I lock the door behind me to be tidy.

Only four bullets left. I should have anticipated that I might need more ammo. But this is Nevada. I can probably find some.

Maybe I can find a friendly dog, also. I love dogs. And it’s not good for people to be too alone.

There might still be some horses out in the northwest valley that haven’t gone totally wild. It’d be nice to have company.

I can get books from the libraries. I’ve got a few months to prepare. I wonder how you take care of a horse on a long pack trip? I wonder if I can manage it on my own?

Well, I’ll find out this winter. And if I get to Reno before the snow melts in the Sierras… I’m a patient girl. And I’ll have the benefit of not having slept through history class. What I mean to say is, I can wait to tackle Donner Pass until springtime.

* * *

The lights that are still on stay on longer than I might have expected. But eventually, one by one, they fail. When I can’t see any anywhere anymore, I make my way down to the Strip with Bruce, my brindle mastiff, trotting beside.

Before I head north, I want to say goodbye.

That night the stars shine over Las Vegas, as they have not shone in living memory. The Milky Way is a misty waterfall. I can make out a Subaru logo for the ages: six and a half Pleiades.

I stand in the middle of the empty, dark and silent Strip, and watch the lack of answering lights bloom in the vast black bowl of the valley all around.

I cannot see so far as Tokyo, New York, Hong Kong, London, Cairo, Jerusalem, Abu Dhabi, Seoul, Sydney, Rio de Janeiro, Paris, Madrid, Kyoto, Chicago, Amsterdam, Mumbai, Mecca, Milan. All the places where artificial light and smog had, for an infinitesimal cosmic moment, wiped them from the sky. But I imagine that those distant, alien suns now shine the same way, there.

As if they had never been dimmed. As if the Milky Way had never faded, ghostlike, before the glare.

I reach down and stroke Bruce’s ears. They’re soft as cashmere. He leans on me, happy.

That night sky would be a remarkable sight. If I had a soul in the world to remark to.

THE RED THREAD

SOFIA SAMATAR

Sofia Samatar is the author of the novels A Stranger in Olondria and The Winged Histories, the short story collection, Tender, and Monster Portraits, a collaboration with her brother, the artist Del Samatar. Her work has received several honors, including the John W. Campbell Award and the World Fantasy Award. Her short fiction has appeared in magazines such as Strange Horizons, Lightspeed Magazine, and Uncanny, and has been reprinted in Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy. She lives in Virginia, where she teaches world literature and speculative fiction at James Madison University.

Dear Fox,

Hey. It’s Sahra. I’m tagging you from center M691, Black Hawk, South Dakota. It’s night and the lights are on in the center. It’s run by an old white guy with a hanging lip—he’s talking to my mom at the counter. Mom’s okay. We’ve barely mentioned you since we left the old group in the valley, just a few weeks after you disappeared. She said your name once, when I found one of your old slates covered with equations. “Well,” she said. “That was Fox.”

One time—I don’t think I told you this—we lost some stuff over a bridge. Back in California, before we met you. The wind was so strong that day, we were stupid to cross. We lost a box of my dad’s stuff, mostly books, and Mom said: “Well. There he goes.”

Like I said, the wind was strong. She probably thought I didn’t hear her.

I think she’s looking at me. Hard to tell through the glass, it’s all scratched and smeared with dead bugs. I guess I should go. We’re headed north—yeah, straight into winter. It’s Mom’s idea.

I’ve still got the bracelet you gave me. It’s turning my wrist red.

* * *

Dear Fox,

Hey. It’s Sahra. I’m at center M718, Big Bottom, South Dakota. That’s really the name. There’s almost nothing here but a falling-down house with a giant basement. They’ve got a cantenna, so I figured I’d tag you again.

Did you get my message?

It’s crowded in here. I feel like someone’s about to look over my shoulder.

Anyway, the basement’s beautiful, full of oak arches. It’s warm, and they’ve got these dim red lights, like the way the sky gets in the desert sometimes, and there’s good people, including a couple of oldish ladies who are talking to Mom. One of them has her hair up and a lot of dry twigs stuck in. She calls me Chicken. It’s embarrassing, but I don’t really care. They’ve got a stove and they gave us these piles of hot bread folded up like cloth. Are you okay? I’m just thinking, you know, are you eating and stuff.

Big Bottom. You won’t forget that. It’s by a forest.

Don’t go in the forest if you come through here. There’s an isolation zone in there. We even heard a gunshot on our way past. Mom’s shoulders went stiff and she said very quietly: “Let’s pick up the pace.” When we got to Big Bottom I was practically running, and Mom’s chair was rattling like it was going to fall apart. It’s cold enough now that my breath came white. We rushed up a sort of hill and this lady was standing outside the house waving a handkerchief.

She took us downstairs into the basement where everybody was. The stove glowed hot and some of the people were playing guitars. The lady gave me a big hug, smelling sour. “Oh Chicken,” she said.

Oh Fox. I miss you.

We’re still headed north.

Tag me.

* * *

Dear Fox,

Hey. It’s Sahra. If you get this message—can you just let me know if you left because of me? I keep on remembering that night in the canyon, when we sat up on that cold, dizzy ledge wrapped in your blanket. You tied a length of red thread around my wrist. I tore off a piece of my baby quilt for you, a shred of green cloth like the Milky Way. You said it was like the Milky Way. The stars rained down like the sky was trying to empty itself, and when you leaned toward me, I emptied myself into you. Did you leave because of the fight we had afterward, when I said my family belonged to this country, we belonged just as much as you? “Don’t embarrass yourself,” you said. Later I said, “Look, the grass is the exact color of Mom’s eyes.” You told me the grass was the color of plague.

You were her favorite, you know. The smartest. The student she’d always longed for. “Fox-Bright,” she called you, when you weren’t around.

Well. We’re still in Big Bottom. Mom wants to get everybody out of here: She thinks it’s too close to the isolation zone. Every night she lectures and the people here argue back, mostly because they have lots of food: They farm and can fruit from the edge of the forest. The lady who calls me Chicken, who seems to be the mom, opens a jar every night with a soft popping sound. She passes it around with a spoon and there’s compote inside, all thick with beet sugar. This one guy, every time he takes a bite he says “Amen.”

Sorry. Hope you’re not hungry.

Anyway, you can see why these people would want to stay in Big Bottom and not try to haul all that stuff somewhere, including sacks of grain and seed that weigh more than me. “We’ve wintered here before,” said the Chicken lady. “We’ve got the stove. Stay with us! You don’t want to go north with a kid and all.”

Everybody was nodding and you could see the pain in Mom’s face. She hates to be wrong. She argued the best point she had. “Sooner or later they’ll come after you,” she said. “You’re too close. You’ve got kids, too.” She said it was a miracle the isolation folks hadn’t already attacked Big Bottom, with all that food. Then everybody got quiet, the Chicken lady looking around sort of warningly, her eyes glinting, and Mom said, “No.” And the guy who says “Amen” over his compote, he told her they’d already been attacked a couple of times.

Mom covered her face.

“We do okay,” the Amen guy said. You could tell he felt bad about it.

Later I got in a corner with the other kids, and I asked about the attacks and one of them, a boy about my age, pulled up his sleeve and his wrist had a bandage on it. He didn’t get shot or anything, but he twisted it hitting somebody. With a crowbar.

When Mom uncovered her face she said: “That’s not the life.” She said: “That’s not the Movement.” She said standing your ground was the old way, not the new, and the Chicken lady said: “Honey, we know.”

After I’d seen the boy with the bandaged wrist, I helped Mom to the toilet and back and we both lay down on the blankets. “We’ve got to get out of here,” she muttered.

“Okay,” I said.

“You know why, right?” she said. “Because we never stand. We move.”

“Sure,” I said. Sure, Mom, I thought. We move.

We move when and where you want, Mom. We’ve sailed back and forth over the ocean. We’ve slept in the airborne beds of Yambio and the houseboats of Kismaayo. And now you’ve decided to go to North Dakota when winter’s starting, through country dotted with isolation zones, leaving all our friends behind. I had such a good art group back in the valley—you saw our last project, Fox. A slim line linking the tops of twenty trees. Wires and fibers twisted with crimson plastic, with cardinals’ wings, making an unbroken trail, a gesture above the earth. It seemed to pulse in the morning light. You said it reminded you of radio waves, of a message. We called it “The Red Thread.”

I’ll probably never see it again.

Such gentle light here, but it couldn’t soften Mom’s smile when she saw me crying. “You don’t know how lucky you are,” she said.

* * *

Dear Fox,

Hey. It’s Sahra. I’m at center M738. Somewhere in North Dakota. The center’s in an old church. At night they feed us pickles and beet soup off plastic tablecloths that an old man carefully clips to the long tables.

They set beautiful candles made of melted crayons on all the windowsills. For travelers. For strangers to find their way at night.

“If we could have known,” says Mom, “if we could have known this life was possible, we would have started living it long before.”

There’s a man with a blunt gray face who argues with her. “You’re one of those human nature people,” he sneered tonight. “The ones who think, oh, we’ve proved that people are good. Let me tell you something, friend. If it wasn’t for the oil crisis and the crash, we’d be living exactly like we were before.”

Mom nodded. A little half-smile in the candlelight. “Sure, friend,” she said, subtly emphasizing the word.

“And another thing,” said the blunt-faced man. “These kids would be in school.”

“Or in the army,” Mom said sweetly.

Of course the kids are in school, because Mom’s around. Wherever we shelter, teaching is her way of giving thanks. She gets all the kids together and makes them draw their names in the dirt, she quizzes them on their multiplication tables, she talks about the Movement. How precious it is to be able to go where you want. Just walk away from trouble. Build a boat and row across the water. When she was a kid, she says, you could barely go anywhere at all: borders, checkpoints, prisons, the whole world carved up, everything owned by somebody. “Everything except light,” she says. “Everything except fire.” And if they wanted, they could keep you in a dark place. Tonight she told the kids what I already know, that that’s where my dad ended up, in some dark place, seized on his way to work and then gone forever. “Why?” a kid asked. “I don’t know,” said Mom. “Because of his name? Because they thought he was working for terrorists? In those days, they could seize you for anything.”

Usually she goes on from here with the story of how the Movement once had another name, how people used to call it the Greening, how the media reported it as an environmental movement first, folks abandoning cars on the freeways, walking, some rolling along like her. She tells of how, in the wake of the crash, the Greening intertwined with other movements, for peace, for justice, for bare life. Grinning, showing the gaps in her teeth, she uses her favorite line: “In the old days, when I worked in a lab, we called it evolutionary convergence.”

Tonight she just stopped after talking about my dad. Her face shrunken, old. And I said: “We might still find him, Mom,” because you never know. When the Movement started, he could have crawled out of that dark space like so many others, the ones you find on the road, cheerful, wearing pieces of their old uniforms. An orange bandana, a gray rag tied on the arm. Tattoos with the name of their prison, where they were kept before the doors opened, before the Movement. I once had a dream that my dad walked down some steps and touched my hair. “We might still find him,” I said. Mom pretended not to hear me.

In the night she woke me with a cry.

“What is it, Mom? What’s wrong?”

“Nothing, nothing,” she whispered. “Go back to sleep.”

I can’t go to sleep. Lying there, I see you walking along a creek. You’re wearing your black shirt and your head’s tilted down, with that concentrating look. I think about how I recited the generations of my dad’s family for you, there on the ledge, at the cave in the canyon wall. My name, then my dad’s, then my grandfather’s, then my great-grandfather’s, back through time. Sahra, Said, Mohammed, Mohamud, Ismail. I can do ten generations. “Amazing,” you said. Your blanket around us and our breaths the only warmth, it seemed, for miles.

“It’s like a map,” you said, “but it shows people instead of places.” You said it felt like the future to think that way.

“Yeah,” I said. “But during the war they killed each other over family lines. Like any other border.”

Belonging, Fox. It hurts.

* * *

Fox it’s Sahra. You knew? You knew Mom was sick? You knew and you didn’t say anything to me? You knew and you left her?

What kind of person are you? It was like somebody walked up and hit me in the chest with a hammer. “I told that boy,” she murmured in the dark room. “I told that boy.” And I knew who she meant. I knew it right away. She said she was sorry. She didn’t mean to chase you off.

That’s why you left? Because you found out someone who loved you was going to die?

I’ve never seen Mom work with a kid the way she worked with you. The two of you scratching away at your slates while the rest of us leached acorns. You’d kneel in the dirt by her chair and rest your slate on the arm. Leaning together, you’d talk about how to make the Movement last, how to keep the meshnets running, how to draw power tenderly from the world, and later you told me that you and I were perfect for each other because we both wanted to draw lines over the land, mine visible, yours in code, but the truth is you were perfect for Mom. You were perfect for her, Fox. “Fox-Bright,” she called you. And you left her when she was dying.

You know what? I’m not sorry for what I said the day after we spent the night in the canyon. I’m not sorry I said I belong here as much as you. They picked up my dad and probably killed him because they thought he didn’t belong here, an immigrant from a war-torn country. But my dad knew this land, he lived in thirty states before he met my mom, in the days of oil he used to drive a truck from coast to coast. He left fingerprints at a hundred gas pumps, hairs from his beard in hotel sinks, his bones in some forgotten government hole. And my mom belongs here, too, even though she cries, can you believe it, my mom, someone you’d look at and swear she never shed a tear in her life, she cries because she grew up in the house we’re living in now, an old farmhouse crammed with noisy families—this is where she was born. She cries because she wanted to come back here before she died. That’s why we’re here. She thinks she’s betraying the Movement by clinging to a place. She lies in the bed in the room where we found a page of her old Bible under the dresser and cries at the shape of the chokecherry tree outside the window. That’s how much my mother loves the Movement that changed our world, the movement she worked for, for years, before we were born, losing her job and her teeth. She loves it so much she’s going to die hating herself.

I’ve cut your bracelet off.

It’s started to snow. I have to go now. Goodbye.

* * *

Dear Fox,

Hey. It’s Sahra. It must be six months since I tagged you. I see you never tagged me back.

Today I left the farmhouse. I cleaned Mom’s room, the room she slept in as a child, the room where she died. Old fingernails under the bed like seed.

There are good people in that house. What Mom called “ordinary people” or, in one of her funny phrases, “the most of us.” They got her some weed, and that made it easier for her toward the end. One night she said: “Oh Sahra. I’m so happy.”

She laughed a little and waved her hands in the air above her face. They moved in a strange, fluid way, like plants under water. “Look,” she said, “it’s the Movement.” “Okay, Mom,” I said, and I tried to press her hands down to her sides, to make her lie still. She struggled out of my grip, surprisingly strong. “Look,” she whispered, her hands swaying. “See how that works? There’s violence and cruelty over here, and everyone moves away. Everyone withdraws from the isolation zone until it shrinks. A kind of shunning. Our people understood that.”

“Our people?”