We, The Six Million E-Book

14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: edition aixact

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: We The Six Million

- Sprache: Englisch

We do not ask here, what can be said historically about the Holocaust and what you need to know or should know about it. We are asking what the people tell us with their fates. We are searching for their meaning for us.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 222

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Reinhold Breil, Christian Bremen and Kerstin Dauvermann (Editors)

WE, THE SIX MILLION

.םינוילימה תשש ,ונחנא

Zukunft gestalten – Geschichte im Blick

Aachener Ansichten zum Zeitgeschehen

Volume 5

Edited by Christian Bremen and Christoph Leuchter

Reinhold Breil, Christian Bremen and Kerstin Dauvermann

(Editors)

WE, THE SIX MILLION

.םינוילימה תשש ,ונחנא

The Reparation-Files of Shoah Victims

.האושה יעגפנל םייוציפה יקית

Translated by

Simone Nothelle-Woters (english)

Impressum

1. Auflage

© 2021 edition_aixact

Alle Rechte vorbehalten

Printed in Germany

edition_aixact

Verlagsgruppe Mainz

Süsterfeldstraße 83

52072 Aachen

0049 (0)241 87343422

www.edition-aixact.de

Gestaltung, Druck und Vertrieb:

Druckerei und Verlagshaus Mainz

Süsterfeldstraße 83

52072 Aachen

www.verlag-mainz.de

www.druckereimainz.de

Abbildungsnachweise (Umschlag)

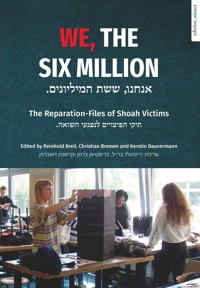

Picture credits cover: “students in art lessons”, photograph by Christina Mehls; backcover left: pupils from KKS school Herzogenrath, photograph from the exhibition “We, the Six Million”; backcover right: “Fred Voss, a Holocaust survivor originally from Aachen, pictured at his high school commencement ceremony in the United States”, photograph by Fred Voss.

Print Book:

ISBN-10: 3-98511-003-4

ISBN-13: 978-3-98511-003-2

e-Book:

ISBN-10: 3-98511-005-0

ISBN-13: 978-3-98511-005-6

The publication was made possible by the generous support of

Introduction by the editors

1. Anti-Semitism – a problem for schools?

Time and again, schools are confronted with problems related to their educational mandate. This seems to us to include the connection of domestic racist anti-Semitism, which is largely believed to have been overcome, with a political anti-Semitism directed against the right of the state of Israel to exist or other forms of anti-Semitism. In addition, this appears to be intertwined with the current migration and immigration issue in an alarming way. In this way, the social reality is reflected in schoolyards: conflicts with an anti-Semitic background are also carried out in the school’s environment, they come from families and peer groups and have an effect there. It seems necessary to sharpen our view on such developments.

Nevertheless, this volume is not primarily intended as a social-pedagogical support for a possible reappraisal of actual anti-Semitic incidents at certain schools. However, the examination of individual biographies of affected Jews before and after 1938 enables a changed view of anti-Semitic and, beyond that, general xenophobic attitudes and behaviour. Education and teaching have a lasting preventive effect: before attitudes and behaviour can be sanctioned, one’s own perceptions must be perceived and changed, enabling one to reflect on one’s own judgements, values and attitudes.

Anti-Semitism, the Shoah and National Socialism are compulsorily dealt with in secondary school lessons, but, as we find, largely in a cognitive way and sometimes like a “curricular topic” in which the personal reference is missing and thus does not do justice to the intention of combating anti-Semitic attitudes. This is not the fault of history and social studies teaching as such, or the commitment of colleagues, but a consequence of changed circumstances. For young people, the Shoah is becoming a “historical” topic with no connection to their everyday lives. The pupils no longer know anyone in their families – great-grandparents and grandparents – who experienced National Socialism. Contemporary witnesses, who were repeatedly invited to the lessons ten years ago, have died in the meantime. It is foreseeable that the National Socialist era will have to be explored exclusively from documents and other sources such as eyewitness interviews or films.

A further word of clarification: We refuse to use the Nazi jargon “extermination of the Jews” or “mass extermination of the Jews”. “Vermin” is “exterminated”, human beings are murdered. We therefore use the term “Shoah” for the genocide of the Jewish people in Europe. The word “Shoah” (great catastrophe), which comes from Hebrew, is used to describe the systematic murder of the Jews during the Nazi era. The term is increasingly replacing the word “Holocaust” which has been used since the 1970s. The word comes from Greek and means “completely burnt”. “Holocaust” was the title of a multipart American television film that used the suffering of a family as an example to describe the annihilation of the European Jews.

2. Compensation and Reparation Files

Can other forms of confrontation and remembrance be found? Don’t we need a different commemorative culture? Let us make it possible to experience and understand what anti-Semitic discrimination, persecution and murder meant for individual, tangible people! How they were increasingly excluded, discriminated against, arbitrarily persecuted, and finally murdered in German bourgeois society. How they were robbed of their material possessions, their civil and human rights, their homes, their freedom and their lives through deliberate impoverishment and persecution.

On the occasion of the 80th memorial day of the pogrom1 on 9 November 1938, selected biographies are presented on the basis of accessible files from the reparation proceedings of the 1950s and 1960s, didactically prepared for work with pupils and placed in the social historical context in an accompanying touring exhibition. In addition to the material presented here, numerous other biographies have been produced; unprinted ones are available at the Institute for Catholic Theology at RWTH Aachen University.2

The files contain the cases whose claims under the (BEG) of 1953 were documented, examined, and decided upon as part of the reparations policy of the Federal Republic of Germany.3 All persons who were victims of National Socialist violence because they held dissenting scientific or artistic positions and directions or were closely related to a persecuted person, and of course the surviving dependents, are considered persecuted.

Each file contains legally verified evidence of life before and after persecution, e.g. witness statements, original documents such as identity cards, court judgements, arrest warrants, etc. Sometimes there are photographs or other visual material, often detention and deportation certificates from the International Tracing Service (ITS) in Arolsen or inventory lists, biographies and detailed descriptions of the persecution situation; occasionally medical reports or X-rays. Often, a major part of the files consists of insurance certificates, statements of assets and their losses, as well as pension and trial files, since numerous decisions were made in court proceedings before the compensation chambers of the district courts. There are also everyday bureaucratic papers such as payment orders or documents of service.

Due to their thematic diversity, the compensation files provide insights into the life and persecution situation of individual persons or families during the National Socialist tyranny up to 1945 and often also enable the reconstruction of individual victims’ fates after the war. At the same time, they show how the West German reparations authorities dealt with compensation claims in the post-war period. For us, they increasingly complement eyewitness accounts by survivors and other historical images, films and text sources. That is why we have decided to use this material for school lessons. We do not ask what the individual must or should historically know about the Shoah. We ask what people tell us with their fates. We understand their meaning for us.

3. The exhibition “We, The Six Million”

On 9 November 2018, members of RWTH Aachen University from the Institute of Catholic Theology, Department of Church History and the Institute of Philosophy presented an exhibition in cooperation with the Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation and the Aachen Memorial Book Project. This was open to the public in the Coronation Hall in the City Hall of Aachen as part of the commemorations and is supposed to be shown as a touring exhibition in schools. The contributions to the exhibition were mainly developed by students of the RWTH Aachen in several seminars and, in one case, by older students of Rheydt-Mülfort Comprehensive School in Mönchengladbach.

The Night of the Broken Glass is the historical point of reference for the presentation, which focuses on Jewish life before and after the persecution and destruction planned and carried out by the National Socialists. The exhibition focuses on the lives of Jewish citizens. The aim is to honour them as individuals, to explain their lives’ achievements and to identify them as shaped by their times. The main theme of the exhibition is the question of which conclusions the exhibition makers, the students and the pupils draw for themselves from this project. This level of reflection forms the bridge to the students’ and pupils’ contribution to the exhibition. The exhibition is based on six basic themes, which together give an overview of the life of the Jewish synagogue community and which each deal with a cultural and economic focus. The biographical work is based on a new source, the so-called “Reparation Files”. They consist of an application and a victim statement with appropriate supporting documents, which are based either on documents from the Nazi period or on sworn statements by contemporary witnesses. The Düsseldorf district council made access possible before the files were handed over to the Archive of North Rhine-Westphalia in Duisburg in summer 2018, where they will then be inaccessible for research for at least a decade.

These sources were supplemented with interviews with contemporary witnesses conducted by students. Furthermore, occupation-specific exhibits from the various fields of work serve to provide a better understanding of life and work at that time. Objects from the personal living environment broaden the view on the scope of the monstrous crimes that were committed. The interviews with contemporary witnesses reinforce this effect. The students’ and pupils’ level of reflection asks how the crimes of the National Socialists are dealt with in right here and now, which means remembering as well as being personally affected and drawing conclusions from them. Thus, the exhibition is based on four different narrative levels, which are based on the six basic themes. The content focus in turn tells a self-contained story that is a reminder, a lament and an appeal at the same time.

Firstly, the four narrative levels show the life and work of Jewish people and how this increasingly changed from 1933 onwards. Secondly, the pogrom of ‘Kristallnacht’ and its immediate consequences represent a serious turning point. The burning of the synagogues and the deportation of Jewish men to the concentration camps were intended as a last warning by the National Socialists to the Jewish population who had not yet emigrated and meant to force them to emigrate once and for all. Those who had not emigrated by the beginning of the war in 1939 found death in the concentration camps. On a third narrative level, not only the restitution files from the 1950s and 1960s, but also the interviews with contemporary witnesses tell of this.

Finally, the fourth narrative level is the level of reflection of the students and pupils. It is characterised by personal approaches to the biographies and fates of those affected. Rational reappraisal as well as artistic-literary perspectives can be seen as an answer to the question of why remembering the Shoah is still necessary today.

The five basic themes of urban and rural Jewry in the city and the former administrative district of Aachen present the characteristics of the different places of life in two exhibition booths. The two booths frame the entire exhibition narrative, so that one booth is positioned at the beginning of the exhibition semicircle and the other at its end. For centuries, the cloth industry formed the economic backbone of the city of Aachen, but also of the large Lower Rhine cities of Mönchengladbach and Krefeld. For Aachen it is shown in its various professional areas. In trade, there were only a few areas in which Jewish entrepreneurs were significantly represented. These included livestock and second-hand goods traders. In the crafts sector, bakers, butchers, shoemakers and painters were mentioned. In earlier times, guild regulations had excluded Jews from membership. The consequences were still felt in the first half of the 20th century. In the independent academic professions, the situation was exactly the opposite. This booth not only focuses on medical and legal professions, but also on university professors.

The exhibition is didactically accompanied and evaluated in school lessons. This can be done either through subject-specific series of lessons or cross-curricular project work. The exhibition is aimed at pupils in grades 9/10 and in the upper grades. These lessons on anti-Semitism, the Shoah and National Socialism, independent of the type of school, add to various subjects by making the forms and effects of anti-Semitism tangible through the example of individual, concrete biographies: discriminatory statements, arbitrary restrictions on everyday school and work life, the increasing arbitrary disenfranchisement of the social environment with work bans and impoverishment, finally life in “Jewish houses” up to expulsion, deportation and murder. The basis for this are selected excerpts from files and the biographies written by students and teachers, which were created based on the restitution files. Historical reappraisal is necessary, but not sufficient. Consequences must be drawn from knowledge of the past: If you don’t know the past, you only know the present, which means you don’t know the future. A further goal is therefore to recognise current forms of anti-Semitism and to develop a critical attitude based on general fundamental values and human rights.

The didactic concept for this was tested during two project days at the Rheydt-Mülfort Comprehensive School in Mönchengladbach with 90 senior pupils. The pupils’ results were presented at the Mönchengladbach exhibition at the end of October 2018 with their own booth. Many pupils were considerably affected when they dealt with the fates of the chosen people, because they encounter people like the Jewish pupil Alfred Voss.

They said, “Now I can imagine much better what happened.” They asked, “how it could come to this” and whether “something like that” could happen again. Our didactic goal is to take up these questions and then discuss them on a general level: How could anti-Semitism and the violence resulting from it be prevented, and does a possible solution not lie in a democratically constituted state and a society based upon our basic values?

Cross-curricular project work is presented as a didactic alternative to work in the classroom. The aim of the accompanying work in class is to evaluate with the pupils a school’s own, also regional, contribution to the exhibition that complements the Aachen exhibition.

4. The Shoah – also a European topic?

Restitution acts are a Western German phenomenon. There were no comparable laws in Austria or the former GDR, because only the Federal Republic of Germany understood and regarded itself as the legal successor to the German Reich. Only people who had lived within the borders of the German Reich in 1937 or who have lived there since the 1950s had a claim. The Shoah was planned and executed by the Germans. Therefore, the successor state of the German Reich is responsible (under international law) for the genocide. On the other hand, the Shoah is also a European phenomenon, since the murder of all European Jews in all countries that came under the control of the German Reich during the Second World War was intended and, for the most part, carried out. In this respect, the Shoah is part of European history.

This raises the question of whether the remembrance of the personal fates of Jewish children, women and men who, as former German Reich Jews, were entitled to compensation under the Reparations Act of 1953, could also be a form of the European culture of remembrance of the Shoah. We believe it can be in at least two ways:

1. Despite all the weaknesses that may be inherent in this law and its implementation in concrete proceedings, it is above all one thing in terms of its intention: it is an attempt to restore the rule of law. It is an attempt to assert Western norms and values as laid down in universal human rights and European civil rights4. In Nazi Germany, Jewish citizens were arbitrarily deprived of their rights. In the former western part of the Federal Republic of Germany, they are once again treated as free subjects of law with equal rights, the outward expression of which is a rather symbolical compensation for injustice suffered. For us today one consequence of this is the enforcement of the values and legal framework of the European Union. Personal fundamental and civil rights must never be restricted or abolished beyond this framework.

2. The personal fates as we encounter them in the files do not only show German but also European fates. Many emigrated “legally” from Germany until 1939, but often first to the Netherlands, Belgium or France. In many cases they did not escape deportation and murder after the occupation. There were various degrees of help on the part of the people and institutions there, but unfortunately also of collaboration. In this respect, the Shoah is a European issue: what did it mean for a Jew to have found refuge in one of these countries or to have been born there, and what happened after German occupation? In a country-specific variation, things, which had their origins in Hitler’s Germany of the 1930s, returned. At the same time, the reparation procedures provide answers to the question repeatedly posed from abroad to those responsible for the academic project, namely how to deal with almost daily news about anti-Semitic incidents in schools and in public in Germany. A new form of commemorative culture is also necessary. The example of Poland (the legal sanctioning of the publicly expressed opinion that the Polish people were also involved in the Shoah) shows how far away from a general European commemorative remembrance we still are. In this respect, commemoration of the Shoah is an expression of a European idea, namely solidarity with victims based on fundamental values such as humanity, human dignity, and human rights.

5. Some thoughts on translation5

English lends itself as the lingua franca to us, the German educators and writers. We chose English for this translated version because it is the most common language among readers of diverse speech in the part of the world where this topic may be of particular interest.

There are, however, some questions which cannot be ignored and have to be taken into account. We ask readers to bear in mind that this is not a thesis or an academic study in the strict sense. It is a book written for educators by educators, providing material, thoughts and ideas in understandable language, be it German or English.

Some remarks intend to explain where and why translation plays an important role when dealing with teaching this delicate topic.

The writers and translators (who are not always identical) were confronted with different text types:

a. The files: official documents from the 1950s, written in asomewhat dated style

We sum up what the documents say, paraphrase relevant paragraphs and focus on their information more than on their style. (Which is deplorable because the style here, as most often, reflects the writer’s or the institution’s attitude…) Here, as in fact with all text types mentioned below, we aimed at finding appropriate words in English for the whole phrase rather than attempting a literal translation.

b. Non-fictional texts and articles

Some texts were originally presented in English or exist as translated versions.

In translating, vocabulary, grammar and style could be adapted, and, where necessary, competent professional translators were helpful.

c. Quotations

Quotations in our original book are mostly in German. Following a widespread and commonly accepted academic tradition, we will treat them like this: We translate them into English as literally as possible and give the original exact quotation in the footnote. Analogous quotations will be marked as such.

d. Literary texts

In the Creative Writing project, literary sources served as a number of stimuli.

Poems, e.g., by Rose Ausländer and Bertolt Brecht, provided a useful frame for students to put their own thoughts and emotions into creative words. But: Is it possible, is it appropriate, is it allowed to translate the works of renowned poets? We think: Yes, otherwise their reception would be limited to a German speaking audience and obviously this is not the case. So here again, we did our best to translate the poems – knowing, that neither we nor our students are poets ourselves.

e. Students’ work

The written products as well as the students’ contributions to discussions are unique, age-specific and highly individual.

The students followed the style of the stimuli, a prompt, a given object. Or a text, a letter or a poem, sometimes including incomplete sentences, enumerations, alphabetical lists. Some were hard to translate, especially if not written in prose. But worth a try.

Transcreation and the aspect of culture

“The culture practised by the speakers of each language may also be vastly different; often, colloquialism is woven into formal language, making the translator’s task very difficult indeed. […] Then the problem arises as to how to translate accurately without hurting sentiments or angering the target audience. Culture is also considered to be a structural translation problem”6.

In the context of translation, we have considered the question of culture, but we feel that it is beyond our means to anticipate how a diverse, international non-German audience feels, speaks or writes about our topic. We are, however, certain that there is nothing in our book that might harm the feelings of its readers. All texts were carefully chosen, the students’ approach, sentiments and products are authentic and honest. Readers will surely realize this, too.

Nevertheless, it would be quite interesting to learn more about the “language of the Shoah” in other countries, meaning a possible special vocabulary, taboo words, coined phrases or any other specific language details unknown to us. The words Reichskristallnacht, Reichspogromnacht, Novemberpogrom,Kristallnacht and Night of the Broken Glass and all their connotations may serve as examples here. But this would be another study.

The term and concept of Transcreation appear rather intriguing in this context.

“The whole point of doing transcreation is to get the gist of the message and transform it into a target language or specific dialect. Transcreation involves not only translation but a creative process as well. A transcreation professional considers the various cultural differences prevalent in each target country […]”7 and though this is entirely convincing, it has to be said that this technique is mostly employed in business contexts in order to “ensure that the marketing and advertising messages of brands and products truly connect with the target audiences”8.

But some aspects of transcreation may also be found in the English version of our book, for the reasons explained in this chapter.

Christian Bremen

On working with the files

1. The Biography

The aim of a biography is to show the path of a person’s life and, in doing so, to reveal his or her personality and his or her role and significance within the context of his or her life.9 The life of the person is to be presented and interpreted within the historical frame. Here too, historical work is based on a triad of interrelated steps. First, the facts must be secured before they are placed in the historical context, which in turn forms the basis for the interpretation.

The so-called “Wiedergutmachungsakten”10 form the basis of the project. For many of the existing files, students of the Faculty of Philosophy at RWTH Aachen University in the seminars of the last semesters have already done this work. If necessary, this can be referred to – as the underlying file material can be referred to. The biographies of Fred Voss, Hans Jonas and Anna Weitzenkorn printed in the appendix are also based on this work. Nevertheless, the methodological approach used will be briefly presented, since students using the material provided can also do some of the work.

First of all, the thematic diversity of these files must be explored. Important biographical contents are:

- origin and family relations,

- schooling and education,

- occupation and offices,

- inclinations and hobbies,

- association memberships: an important indicator of participation in social life,

- history of persecution,

- children and grandchildren.

Some files allow us to discover the personality and uniqueness of a person.

Each file describes a different person. It is important to work out the individuality. Therefore, in a second step, important documents can be found in the file.

Besides pictures of the persons, these are above all historical sources. Among them are all traces of the past. Official Nazi letters are just as interesting as diaries, letters, testimonials and identity papers.

Once the contents of the file have been indexed, two methodological approaches reveal themselves. If there is sufficient material, a chronological approach is the best. The advantage is obvious: the life story with all its discontinuities can be told one after the other, in order to make all changes visible and often prove to be self-explanatory. If there is too little material, the thematic form of presentation is the only way. On the other hand, if there is too much information, a mixed form can be used.

The basic grid would be the chronological approach. Within this approach it is possible and desirable to dwell on selected topics at any time and by doing so to archive more depth. The chronological approach takes into account the ancestors, origin, parents and siblings, followed by school and education, apprenticeship, studies and profession. Important life events (marriage, wife/husband, children), especially the history of suffering, are to be presented; if emigration took place, also life after 1945.

The Jewish community in Aachen did not form until the 19th century, so that the question of origin is a worthwhile and especially promising research.

In some cases, even further answers can be found according to the ancestors.

Concerning the parents, one should not only ask about the date of birth and death but also about the places where they lived. The “Sitz im Leben” (position in life) should be described: social and societal life is of interest. If there are, siblings should be described as biographically detailed as the main character. It is amazing how much information the sibling files contain about the person to be described. It is therefore always advisable to write a family biography. An example of this is the Leib family, to which Anna Weitzenkorn belonged.

For the thematic presentation, the topics are determined by the contents of the file; in the file of Anne Leib for example, there is evidence of the deportation history up to the murder in the concentration camp.

A biography is not only descriptive. After securing the facts and integrating them into the historical context, interpretation is required. An example of this is the given name and school attendance, which can be broken down according to the following pattern11:

Fact

Historical background

Interpretation

Name: Siegfried

Song of the Nibelungs, most German of all sagas

patriotic or nationalistic family background

School: Kaiser-Karl-Gymnasium

12

educated bourgeois education (Latin and Greek)

career goal: an academic

School: Secondary School

career-oriented, modern languages (English or French)

career goal in business, e.g. business succession or business management

A portrayal that integrates the environment into contemporary events thus includes the family, the city and its self-image, professional life and the social environment. A person’s life should be shown in its entirety and in interrelation with the social, political, religious and economic conditions of its time. Often these biographies are contributions to urban civic research.